|

CCC Forestry

|

|

Chapter II

FOREST VALUES

|

|

||

|

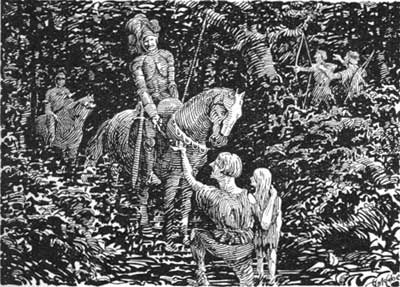

FORESTS offer various values and benefits to man. These may be lost through destructive lumbering, fire, tree diseases, insect attack, and improper management. The relative importance of forest values changes. The early Greeks worshiped among the trees. Many of their gods and goddesses were reputed to live in the woods. The Druids deified the oak and worshiped in the forests. In medieval times, when civilization came to Western Europe, nearly all the land was forested. History and literature reveal the customs of the day. Robbers hid in the forests. Hermits and peasants lived a simple life, gathering fagots, berries, and other products of the forest. Herders led their sheep, goats, and swine into the forests to feed. Kings and nobles hunted and knights traveled the trails seeking adventure.

Forest values then were different from those of today, yet forests have undergone no essential change. The values of the forest, however, change with the needs of the day. Present day needs, and those forecast for the future, demand more and better managed forests. Forest values may be divided into two main groups: products and influences, one as important as the other, in general. The head is no more important to the human body than the heart, and it is absurd to say that one is more valuable than the other. Likewise, the products we derive from forests and the desirable influences exerted by them cannot be evaluated. Both these values are vital to the needs of our modern civilization. Individual demands for timber are not as great as they once were. As a value, however, timber holds its own. The use of steel and copper has likewise declined, and these cannot be renewed. The use of wood is highly important to man. Wood to keep people warm and to cook their food has value. Wood has value in communication systems, which use millions of telephone and telegraph poles. Wood has value in transportation, as shown by its use in wagon and carriage construction, automobile manufacturing, and as railroad ties. Of all wood products, sawed timber is used more than any other form. It has value both in manufacturing and in building. But forests offer many other values. Tree extracts such as turpentine and rubber are used universally. Other products derived from wood are paper, wallboard, and cellulose products, dyes, medicinal compounds, and chemicals. The varied forest products, their relative values, consumption, and methods of utilization will be taken up in another chapter. Forest influences may be divided into two main groups: Physical and social. The physical influences affect climate, stream-flow, and soil. The social influences have to do with employment, income, standards of living, and recreation. Both groups, the physical and social, directly or indirectly affect the well-being of man. |

| |

|

|

||

|

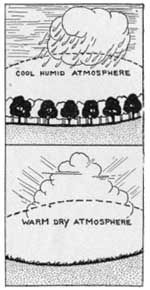

EFFECTS OF FORESTS ON TEMPERATURE AND HUMIDITY In summer when cities are sweltering, people throng to forests for recreation and rest. They know that wooded glens and breeze-swept mountains are more comfortable, cooler, and more invigorating than torrid streets. Why are forests comparatively cool in summer? One reason is that higher elevations are usually cooler than low elevations. But there are factors other than elevation, factors inherent in forests themselves, that tend to reduce summer heat. First, the leafy canopy protects the forest from the hot rays of summer sun; second, trees transpire water through their leaves and since evaporation is a cooling process, the evaporation of this water greatly reduces heat in the forest—just as evaporation cools a person when he perspires; third, the movement of hot currents of air is checked by standing timber. Within a forest the temperature changes are not so great as in nearby open areas. Maximum forest temperatures are lower, and minimum temperatures higher, than those of adjacent fields. Raphael Zon, reporting observations over long periods in European forests, stated, "During the hottest days the air inside the forest was more than 5° F. cooler than that outside." It was found that for the coldest days of the year the air in the forest was 1.8° F. warmer than that outside. Sir William Schlich has shown that, during the summer, night temperatures are higher and day temperatures lower, in forests than in nearby open areas; the minimum at night being 3.15° F. higher, and the maximum in the day 7.42° F. lower. Relative humidity under forest cover may be as much as 10 percent higher than that of adacent open areas. (Relative humidity is a comparison of the actual moisture content of the air at a given temperature with the possible amount the air is capable of holding at that temperature.) Zon reports that, in studies made in Bavarian forests, relative humidity inside the forests was found to be from 3 to 10 percent higher than that outside, the least difference occurring in winter and the greatest in summer. Like the moderation of temperature this condition is a result of shade, retarded air currents, and transpiration. Trees, especially thin-leaved species, give off much water through transpiration. Transpiration is a natural process associated with the tree's growth, by which water is released through the stomata or leaf pores. A comparable process is perspiration in humans. It has been estimated that a fully stocked beech stand, 115 years old, uses from 1,560 to 2,140 tons of water per acre per year, practically all of which is returned to the air as transpired water vapor. |

| |

|

|

||

|

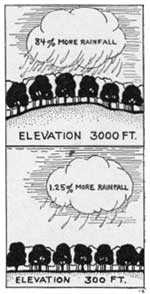

Rainfall is caused by the chilling of moisture-laden atmosphere. At varying degrees of temperature, air is capable of supporting varying amounts of vaporous water. The higher the temperature the greater the water-holding capacity of the air. When warm air, carrying a heavy load of moisture, is suddenly cooled its water-holding capacity is lessened, and the excess water falls as rain. As we have seen, forest areas are cooler than open areas and are always more humid. These changes of conditions extend farther than the forest itself. Just as a block of ice in a room tends to reduce the temperature of the air surrounding it, so forests tend to cool the atmosphere surrounding them and to make it more humid. Observations made in balloons show that these effects are still discernible at elevations of 5,000 feet. Moisture-bearing clouds encountering such cool and humid atmosphere, decrease in water-holding capacity and release their surplus moisture as rain. That this phenomenon actually occurs in nature is borne out by studies in Europe. In some cases more than 25 percent increase in rainfall upon forests has been recorded over long periods as compared with adjacent unforested areas. This effect on precipitation is most noticeable at high elevations. Observations show that up to 300 feet in elevation forests increase rainfall only 1.25 percent, but between 3,000 and 3,250 feet the increase may be as much as 84 percent. It is the opinion of experts who have given much thought to the matter that the local effects of forests on rainfall are less important than those over large areas. Forests are known to transpire large amounts of vaporous water into the air. Whereas saturated air currents are cooled and lose moisture in passing over a forest, dry air currents are enriched in moisture by contacting atmosphere over a forest. Inland precipitation depends largely on the character of the land cover over which the prevailing winds pass after they have discharged their moisture. Water is taken up by these winds in the form of vapor. The more surface exposed to the air, the more evaporation will take place. A forest exposing more surface (ground, plus stems, plus leaves of trees) than do similar unforested areas, therefore, contributes more to the moisture content of the inland air currents, and to the amount of rainfall. Zon contends that the moisture-laden winds from the Gulf of Mexico lose much of their water content as rain in passing over the lands near the coast. They then become dry, and precipitation ceases. If these winds did not have sources other than the ocean from which to regain moisture, rain would be confined to a narrow border along the oceans, and the interior would be quite dry. These other sources, he maintains, are the forested and vegetated areas. |

Air Carries Water Vapor.

Like a Block of Ice.

| |

|

|

||

|

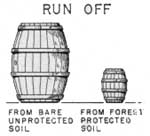

The wearing away of land surface by water depends upon four factors: (1) The amount of rainfall; (2) the degree of slope; (3) the composition of the soil; and (4) the cover of the soil. It is evident that man cannot greatly control rainfall, neither can he change the degree of slope or the character of the soil over extensive areas. But man can control the vegetative cover on the earth's surface and can help control erosion in this manner. Life is dependent directly or indirectly upon soil. Since this is the case, it is of great importance that the best types of soils be protected. Forest vegetation is one of the best builders and retainers of soil on extensive areas, especially where steep slopes increase the force of erosion. Erosion may destroy valuable soil or impair ground surface so that it is very difficult to reclaim it. For this reason forests should cover the greater portion of steep slopes and nonagricultural lands capable of supporting trees. Erosion starts when rain falls upon poorly covered or bare soil and is moved by gravity to lower levels. As it moves it carries particles of earth. The greater the volume and force of the water, the greater the force of erosion. On open areas where soil is hard and compact, very little water is absorbed by the earth. This means that there is a greater run-off. There being no surface litter to check the velocity of the current, water accumulates into torrents resulting in greater erosive forces. In forests, rains fall upon the leaves and branches of the trees. This reduces the impact with the ground. Rain from the trees drips upon the litter-covered forest floor and its run-off is obstructed by leaves, twigs, and plants. The water then gently enters the fibrous, porous soil of the forest and slowly runs into underground passages where it gradually finds its way into reservoirs and later into springs and streams. Much of the water is held by the spongy earth to percolate gradually into these streams, causing streams in forest areas to be much more constant in flow than those in unforested areas. Studies by the Wisconsin Experiment Station show that on slopes of 36 percent wild pastures (grass cover) had run-off 2-1/2 times as great as that of hardwood forests; and on cultivated and fallow ground, the run-off was 9 tunes as great. Many similar studies reveal like data. Phillips and Goddard, of the Red Plains Experiment Station at Guthrie, Okla., found that burned areas in a forest eroded 15 times as fast as unburned areas (same slope and soil).

Generally wind erosion does not do as much damage as water erosion. However, the wind does cause damage to soils by blowing sand over valuable areas and by drying and reducing exposed humus. The recent dust storms in the Prairie States show the extent of damage possible by wind erosion. Forests reduce wind effects and retard drying. The Shelterbelt of the Middle West is an experiment to test the value of plantations for eliminating ill effects of winds and dust storms. The extreme effects of forest destruction and the subsequent action of wind and water on soil and economic conditions may be seen in parts of China where floods and erosion have reduced the productivity of farms and have choked the rivers with deep deposits of mud. If forests are not disturbed in the process, they form their own valuable soils. This accumulates on the forest floor in the form of leaves, twigs, rotting branches and logs, and decayed plants and animals. Roots and partially decayed twigs make the soil porous and the constant working of bacteria and minute animal life reduce the debris to humus. Humus thus formed, works into the subsoil to combine with the chemical elements of the subsoil which are transferred to the upper layers so that a light, porous soil, rich in food elements, is the result. |

Percolation.

| |

|

|

||

|

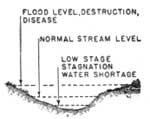

In practically every section of the country the question of stream flow is of major importance. In centers of population, much water is required for domestic and commercial use. In many sections seasonal droughts cause streams to become low and sluggish or to dry up entirely. The problem of fluctuating flow seems to grow more acute, and maintaining the normal flow of water from watersheds is one of the important objects of forestry. As vegetation, especially forest cover, is removed from slopes, run-off is accelerated. Accumulated run-off causes floods which sweep away millions of dollars worth of property, and do vast damage. According to early estimates (the only figures available when this publication was printed) the Ohio and Mississippi flood of 1937 took 400 lives, drove 1,000,000 people from their homes, and caused property loss totaling $500,000,000. Besides flood losses in homes, livestock, and farm soil, stream beds are clogged with soil and debris, navigable channels and reservoirs are filled, roads and bridges destroyed. Debris and eroded soil are often deposited on valuable farms, and in roads, streets, and buildings. Permanent forest vegetation of watersheds cannot cure all the ills of floods. Of course stream flow will fluctuate, but rivers flowing from wooded watersheds have a constancy which streams in open country cannot possess. Their high water marks are lower and their low water marks are higher, and it is the critical extremes of water flow which demand the greatest consideration. In the description of the forest floor and the discussion of soil and erosion, attention was called to the fact that spongy, porous soil absorbs water from falling rain and melting snow much more readily than more compact soils. Forest litter absorbs surface water and prevents rapid run-off. The same litter prevents rapid drying out and freezing of subsoil water. This leaves more water in forest soil to find its way slowly into streams. Thus forests help to regulate the flow of streams. Rivers which have dependable water flow offer greater values than do streams whose flow rises and falls extremely. The more forest area we have, the more and better protection we shall have from floods.

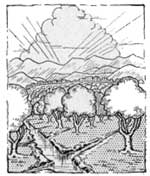

Water supply: Where population is concentrated, it is necessary to draw water for domestic and commercial use from large streams. If these streams are likely to flood easily in wet seasons and then become low and sluggish in dry seasons, they are not dependable sources for water. Streams not fed by fresh tributaries during hot, dry weather become contaminated and it is necessary to go to much expense to purify the water. Water heavily treated with chemicals is unpleasant to taste and in many cases not suitable for commercial use. Forest-fed streams are generally clearer, fresher, and more constant in flow than streams in open country. Along 300 miles of the eastern seaboard, cities use 2 billion gallons of water daily. New York draws water through aqueducts 92 miles long, and Boston has tapped a stream 60 miles away. Three cities in the East have spent 150 million dollars in recent years building dams and filtration systems. More and better forests would help reduce such outlays. San Francisco and Los Angeles, Calif., obtain water from reservoirs 200 to 250 miles away. The importance of water for home use, commercial use, and livestock consumption is apparent. The great drought of 1930-31, when cities were required to transport water by trainloads, and farmers were obliged to truck water over long distances, demonstrated the necessity of better provision for water supply. Foresting watersheds of supply streams would improve the situation. Irrigation: Early settlers in the western United States braved the dangers of a rugged, untamed country, lured by adventure and the gleam of gold. Backs were bent over pans of swirling gravel while eyes squinted and reddened peering for "pay dirt." Today the pay dirt of the West is the irrigated land of the semiarid regions. The gold of the Golden West lies in the orange groves of California, the produce of the Imperial Valley, the sugar beet fields of Utah, and the alfalfa and potato crops of Idaho.

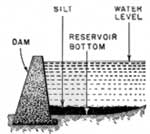

Irrigated lands in Colorado produce annual crops worth more than the aggregate of all its mines. Agriculture is now the most important industry of the Colorado River Basin. Water from the Colorado supplies millions of acres of irrigated farm land. Thousands of homes have been built and thousands of families depend upon irrigation canals. The Imperial Valley of southern California, sending fruit and produce to practically every market in the country, is a rich, fertile area which owes its prosperity to irrigation. According to the 1930 census, 19 States eastward from the Pacific coast, into Arkansas and Louisiana, contain 19,547,544 acres of irrigated land, with $1,032,755,790 invested in reservoirs and distributing systems, and $4,886,892,784 in lands, buildings, and machinery. This total investment of nearly 6 billion dollars is wholly dependent on water, and since the majority of streams which supply the water for these vast irrigation projects originate in the forest, protection and care of these forests is of primary importance. Large storage basins and dams supply the water for the more extensive projects. Huge reservoirs are often located back in the mountains, at considerable distance from the water users, where they can obtain silt-free water from the forest. Many of the smaller irrigated farms are entirely dependent upon the forests for regulated water supply. Forests and water power: Falling or rapidly flowing water has long been used as a source of power. The first water developments made use of paddles or wheels to turn machinery situated near streams. Many early sawmills and grist-mills in this country were of this type. The necessity of locating such mills at the water's edge limited their possibilities. With the development of electric power, energy produced by water could be transmitted many miles from the stream. Although the direct or mechanical power of water is still used to operate mechanism near its source, the greatest power plants are those which transform mechanical power to electric energy. Water turns huge dynamos which produce electricity to flow from the plant and supply light, heat, and power in cities, homes, and factories. The distance to which electricity can be transmitted is limited, however, and additional water-power plants are located only where their cheapness and dependability surpass those of other power sources. Where water-power plants are economically practical in the United States, forests are important factors in assuring the necessary water supply. It has been estimated that more than 72 percent of the total water sources of the country is in the forested mountains of the West. Because of its remote location, much of this power is undeveloped. The United States Geological Survey finds that more than 30 percent of the Nation's actual water power is produced in the Northeast where cities and factories are close to forest-fed streams. Seventy percent of all the industrial and public utility power in Maine is water-developed. California produces more horsepower from water than any other State, but much of her water power resources are unused. Boulder Dam is expected to produce $6,500,000 worth of power annually for the Southwest, in addition to supplying water for irrigation and domestic use. In the Northwest water power is increasing in importance and the forests of that region help to regulate stream flow. The Northwest is far from available coal supplies, but it has a wealth of forest-fed streams capable of producing cheap power. With the further development of cities and industrial centers in that section, water may surpass all other sources of power. The South Atlantic drainages are typical of the water power possibilities to which forests can contribute much in the way of regulation. The maximum or flood flow of the more important streams in the South is from 150 to 400 times the minimum or dry season flow. During wet seasons water flows rapidly from deforested land, but in dry seasons the flow is not enough to supply the power demands. It has been necessary to construct dams and reservoirs to hold the water of rainy seasons for periods of light rain or no rain, and thus to maintain regular power production. Large amounts of silt carried into these basins from deforested land have increased greatly the cost of an otherwise cheap power source. Erosion control by forest cover will do much to obviate this difficulty. Forest cover assists in the underground storage of rain water, and streams regulated by adequate forest growth supply a more dependable flow of water than do streams from barren or sparsely covered land. Power plants might be constructed, with no reservoirs or but small reserves, on forest-fed streams in anticipation of consistent flow throughout the year. Such plants may be operated fully in dry seasons, entailing no loss of investment in idle machinery. Without regulation, the water flow in flood seasons is often too great to be fully utilized, and is entirely inadequate in periods of drought. Although in many regions coal can now produce power more cheaply than water power can be transmitted from plant to consumer, coal is a resource that cannot be replenished. Power companies have improved their methods and machinery for greater efficiency, but the supply of coal cannot be renewed; as this supply decreases and the demand for power and utilities increases, forest-fed streams will become more important. |

Even Stream Flow an Object of Forestry.

Forest Floor, p. 20.

| |

|

|

||

|

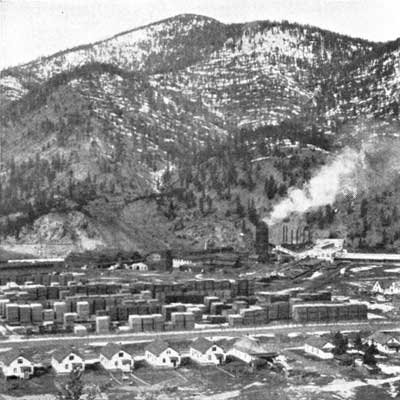

THE FOREST AND EMPLOYMENT Forests directly and indirectly furnish means of employment to millions of people. Men may work in the woods improving conditions for tree growth; they may work in the harvesting of forest products; they may work in the transporting of forest products and they may work in the manufacture of forest products. One of the most important values of forests is their ability to furnish jobs for workers. From the time that tree seeds are planted until a wood product, a rayon garment for example, is sold over the counter of a department store people are paid for duties performed in preparing it for human use. In Europe there are some sustained-yield forests employing one man to every 40 acres in producing and manufacturing timber; but in most of the managed forests the ratio is about a man to every 250 acres. In the United States where figures were available on sustained-yield projects, the ratio was one full-time worker to every 240 to 360 acres. In 1929, about 1,300,000 full-time workers were employed in forests and wood manufacturing. Part-time employment would bring this well up to a million and a half workers. Properly managed and utilized forests in the United States could probably employ two million workers steadily. This is one of the forest's greatest economic and social values. THE FOREST AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Forests, of themselves, do not stabilize communities nor insure communal permanence; but forestry, that is, the wise use of forest land, may assist in supporting permanent, thriving communities. The country has many "ghost towns"—the result of rapid increase of forest and mill workers during boom times and the subsequent decrease when the mill ceased operations. In these instances a wood supply was discovered, a market developed, a town built up, schools and churches established almost overnight. When the wood supply became exhausted the livelihood of the community was taken away. Forestry, through sustained yield of forest products, tends toward regulated markets and permanent industries and communities. A forest enterprise operated on a sustained-yield basis, which determines an annual cut not exceeding the annual growth, will last indefinitely. Communities built around such enterprises form lasting markets for agricultural and manufactured goods. Communal dependence upon forests is illustrated in Grays Harbor County in western Washington. This area of 1,196,000 acres, 956,000 of which are logged off, supplies 71 wood-using industries and 31 logging companies supporting a total of 10,150 workers. Other industries and services bring the total population of the county to 60,000 people, all more or less dependent upon the forest.

In Louisiana, Bogalusa supports a population of 14,000 with forest products industries—pulp, paper, naval stores, woodenware, and furniture. Cloquet, in Minnesota, was rebuilt following the great fire of 1918. The future of its 7,000 population and its numerous wood-using industries, which seems secure, depends upon the practice of forestry. Fortunately, these enterprises are planning systems of sustained annual yield. When thriving communities such as these are compared with the twin lumber towns of Au Sable-Oscoda in Michigan, which in 1890 had a population of 8,346 and in 1930 only 903, the value of forestry practices becomes strikingly evident. An important phase of forest employment that has been provided in State and national forests is the part-time work for farmers, factory workers, and local woodsmen. In Europe this form of employment is highly developed. The Forestry Commission of Great Britain has a "small holdings project" under which the agricultural land in the Government forests is set aside for farm use. The land is leased in 10-acre lots, equipped with small farm buildings. Each tenant leasing one of these holdings is guaranteed 150 days work in the forest. This gives him a cash income and allows sufficient time for growing farm produce for his own consumption or for sale. In France, Germany, Austria, and Finland, many farmers are employed part time in the forests. A large number of small farms in this country, although they supply the family food needs, are not capable of producing incomes for their owners. In many forested regions it is possible to employ these men for a period of 5 or 6 months in the woods. This plan allows them ample time to raise small crops, and gives them from $300 to $400 per year additional. In this way considerable necessary forest work may be accomplished for which a full-time crew would be unwarranted, and small farms and local industries may become more stabilized. This plan is being carried out on many State, national, and private forests. It is possible to extend these part-time enterprises wherever small agricultural holdings abut on large areas of forest land. In some sections of the country—Connecticut, for instance—it has been estimated that 500 men could be employed for 6 months each year on the State forest of 63,000 acres. That would average one man for 6 months on each 126 acres. Although this same figure may not hold true in all sections of the United States, it gives some indication of the part-time employment possibilities. Many students of industrial and social economics believe that manufacturing plants should be spread over the country instead of being grouped together in large industrial centers. One of the country's largest automobile companies has decentralized parts of its industry and has been quite successful in the enterprise. Fourteen of its small plants have been established in rural districts where agricultural products used in the manufacture of automobile parts may be grown, or where produce for home consumption or sale may profitably be raised. When the factories are closed, the men work on their farms. The plants, employing workers seasonally at a minimum wage of $6 per day, add approximately $600 to each farmer-employee's yearly income. The same idea may be, and is being adapted to forest work. Industries with seasonal fluctuations of employment, particularly wood-using industries or those that can use the water power of forest-fed streams, may be situated in or near forest areas. A factory-forest community similar to the factory-farm community, or the farm-forest community, may be realized if other large companies see the advantages of securing all year employment for part-time employees. If seasonal periods of factory employment can be coordinated with seasonal fluctuations of forest work, a permanently employed community can be set up.

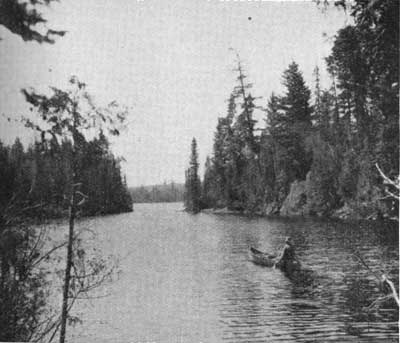

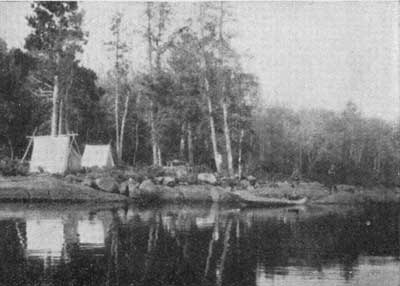

RECREATION Recreation is anything done for the direct pleasure or enrichment which it brings to life, in contrast to things done primarily to obtain life's necessities. The health-giving properties of forest recreation have long been recognized by the medical profession. Health resorts and sanitaria are located in forested mountains where the effects of pure air, sunlight, and outdoor recreation combine in the battle against disease. It is regrettable that everyone cannot spend a few days in the woods each year. Forests usually are not near big cities and population centers. Many of those that were so located have been used and destroyed. Existing recreational areas must be protected from fire, since fire often completely destroys forests and always renders them unfit for recreation. Forests should be protected from exploitation; the trees should be cropped, rather than mined, to maintain beautiful wooded areas best adapted for recreation. Picnicking is perhaps universal as outdoor entertainment, and in some regions is the most popular form of forest recreation. It requires no extra equipment for the picnicker and takes no time from work or business, using Sundays and holidays principally for this purpose. An important feature of the day-in-the-woods form of entertainment is the low-cost feature. After picnicking, camping is next in popularity. Getting outdoors and living in a primitive manner appeals to almost everyone. There is definite value in the soothing restfulness of living outdoors. Climbing mountains is better exercise than riding elevators. The boy and girl who learn to take care of themselves in camp become better fitted to live at home. Camping has far-reaching advantages to the individual and to society. The future of this great recreational activity depends largely upon the future of forests. Hunting and fishing often are part of the camper's program, but generally followers of the gun and rod take their sports seriously and go to the forests for no other purpose. However, a good huntsman or fisherman enjoys the whole outdoors, and does not limit his pleasure to the conquest of game. The demand for more game and fish is evidence of the value of forests in furnishing facilities for satisfaction of the desires of millions of sportsmen. Other forms of forest recreation cannot be distinctly divided from camping and picnicking. Enumeration of these activities will, however, help to picture the true role of the forests in a recreational program for a people who are for getting how to play. Hiking appeals to the nature lover and outdoors person. Swimming in cool forest streams is refreshing. Opportunities for nature study abound in the woods; plants and animals are available to the naturalist. Birds flee the dangers of populated areas and find sanctuary in the woods where bird lovers may study them. The values mentioned above are real, and tangible or physical. There is another value, often called spiritual, that may be secured by everyone. Something deep within us urges us to get out of doors where in the quiet of the woods big troubles become little ones; we orient ourselves with the general scheme of things, and are refreshed and rested.

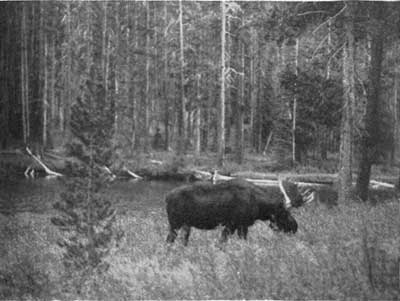

WILDLIFE Wild animals, birds, and fish are included in a general term: wildlife. This wild population of wood and field has definite value. Lack of figures for forests alone limits a discussion of wildlife in the forest, but practically all wildlife depends wholly or in part on forests for food, cover, or both. The Biological Survey has set a value upon all wildlife. This is of course approximate, but an estimate of the value of meat, fur, destruction of insects, hunters' fees, and money spent by hunters and tourists in game country, indicates that the total value is well above a billion dollars. At one time, wild animals played a very important part in the economic life of the Nation. They furnished both food and clothing for the pioneer. Vast fortunes have been built upon fur trade, and today trapping forest animals for fur is a paying occupation. The greatest value of wildlife is not economic. The social benefits derived indirectly through stimulating outdoor recreation are probably greatest. Esthetic and scientific values are also worthy of consideration. |

What are the Forms of Forest Recreation?

| |

|

|

||

|

Forest values have two main divisions, namely, forest products and forest influences. The principal product of the forest is wood, and many valuable commodities are obtained from wood. The product having the most value is lumber. The annual use is about 35 billion board feet. This is used in construction and manufacturing. Other than sawed timber, fuel and pulpwood are important as values. Chemicals, dyes, and medicinal products are also obtained from wood and forest plants.

Forest influences are physical and social. Physical influences are those affecting temperature, humidity, rainfall, stream flow, and erosion. Social influences are those affecting employment and healthful living. Forests and forest products manufacture provide employment for many workers. Forest recreation makes living conditions more healthful and more enjoyable. |

Forest Products.

| |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

ccc-forestry/chap2.htm Last Updated: 02-Apr-2009 |