|

CCC Forestry

|

|

Chapter III

FOREST CONSERVATION

|

FORESTS OF THE PAST |

||

|

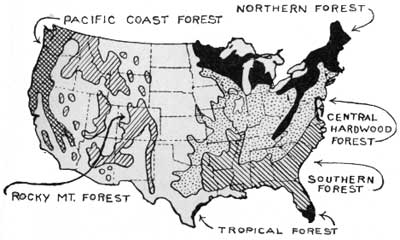

EARLY explorers on this continent were confronted with a vast expanse of forested land—a seemingly unbroken wilderness. Later, colonists and inland explorers found that slightly less than half the total area now occupied by the United States, or almost 900 million acres, was covered with some sort of forest growth. Natural regions: From the Atlantic seaboard to the prairies across the Mississippi was a continuous, almost uninterrupted, region of trees. Prairies and grasslands extended to the Rockies where forests again began to appear. The Pacific coast presented a belt of forested land—quite extensive in the North and tapering southward in two points to disappear in the southwestern scrub oak and chaparral. Climatic conditions separated the forests into huge natural regions. In the East were four regions—the northern forest, the central hardwood forest, the southern forest, and the subtropical forest. Two groups comprised the West—the Rocky Mountain forest, and the Pacific coast forest.

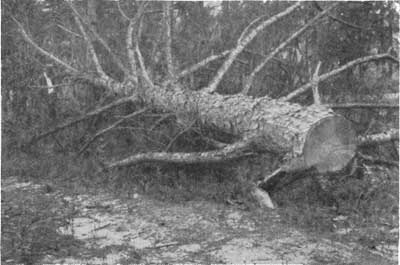

About 150 million acres of spruce, balsam fir, white pine, hemlock, arborvitae, and hardwoods made up the northern forest; further south and at lower elevations, beech, birch, maple, and other hardwoods appeared. In the central hardwood forest were 281 million acres of broad-leaf trees, principally oaks but including many other species. White pine, pitch pine, and hemlock mixed with the hardwoods in the North and shortleaf pine grew in the South. The southern forest of 250 million acres was largely pines—longleaf, slash, shortleaf, and loblolly—with cypress and white cedar in the swamps and hardwoods on the better lands. On the southern tip of Florida a tropical growth was prevalent consisting of mangrove and other tropical species. In the West, the Rocky Mountain forest, 65 million acres in extent, was composed largely of softwoods or conifers—pine, hemlock, cedar, fir, and spruce—in the North, with piñon and junipers in the South. The Pacific coast forest of 80 million acres contained the giant Douglas fir, redwood, bigtree, yellow pine, cedar, and some hardwoods. In southern California scrub oak and chaparral predominated except at high elevations where pines, principally Coulter and yellow, were found. Early forest use: Of this total forest land area, approximately 820 million acres held good timber; about 80 million acres in the Southwest was covered with a scrubby growth of chaparral and stunted trees (now, because of the water demands of an increased population, important as watershed protection). The trees had been undisturbed by the woodsman's ax. Large, mature, and overmature trees awaited a natural death to return them to the soil from which they sprang. Settlers looked upon the trees as both friends and enemies. Here was wood with which to build homes, ships, furniture, and workshops. Those same trees provided cover under which hostile natives might advance upon the puny settlements; trees grew thickly on land that could be lush meadows for cattle. With these thoughts in mind the colonists proceeded to cut wood for buildings and stockades, and to clear large areas for farming. Although the cutting and clearing practices of the colonists might be considered wasteful in the light of present-day standards, they were necessary operations at that time. Few people realized that the vast wealth of timber would some day be exhausted. The lumber industry: As the population of the New World increased, more land was cleared for agriculture, and a thriving lumber business developed. Maine made an early bid for lumbering supremacy; in 1631 the first commercial sawmill made its appearance in that colony. Shipbuilding and home construction in the early nineteenth century established a demand for white pine lumber; a growing export trade put American wood on all the world's markets. From Maine the center of the industry moved to New York (1850), then to Pennsylvania (1860). The next movement was westward to the Lake States (1870). Thus practically all the accessible virgin white pine was cut. Lumbermen then turned to the southern yellow pine which has also been largely cut out. Today the bulk of the virgin timber is in Washington, Oregon, northern California, Idaho, and Montana. Small portable mills continue in the other regions, but the large operations are confined to the Northwest and to isolated regions of the South.

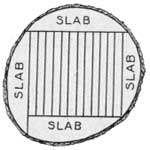

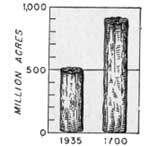

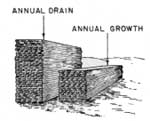

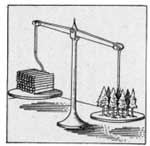

Early lumbering methods were wasteful. Much good wood was left in high stumps, small logs were not utilized, and large tops remained unsalvaged. In the mill, unnecessarily large slabs were trimmed from the logs, and thick saws reduced up to 20 percent of the wood to sawdust. In the East, hemlock was cut only for its bark, which yielded tanning substances. The wood, not as profitable as white pine, was left to decay in the woods. The remnants of these giant hemlocks may still be found in many eastern forests. Lumber prices rose as the supply of big timber vanished. Trees formerly left standing as worthless were eagerly sought by the operators of small mills. Stumps were cut lower, tops were bucked up into merchantable logs, and milling practices became more efficient. In spite of these efforts to eliminate waste, it has been estimated that from 20 to 60 percent of the total wood volume, depending on the size and form of the tree, is still lost in cutting and milling. Of the original 900 million acres of forest land, about 500 million acres are capable today of producing timber in commercial quantities. Most of this land is in second-growth timber from which high yields cannot be expected for some years to come. Approximately 60 billion board feet of saw timber annually are removed by lumbering, fire, and other agencies, from American forests. The drain on saw timber and cordwood for the period 1925-29 was nearly twice the growth. Improved forestry practices, reforestation of idle lands, better lumbering and milling methods, and closer utilization will tend to balance, in the future, the ratio of growth to drain. Although an abundance of timber covered about half of the country in early colonial times, a small group of far-seeing men realized that uncontrolled stripping of the forests if continued would, at some future time, result in a dearth of wood supplies. After settlements were well established, colonial leaders attempted to prevent wholesale forest destruction. Plymouth Colony and Pennsylvania were among the first to establish regulatory rules. The Federal Government, as early as 1799, established forest reserves to supply ship timbers for the Navy.

|

The national forest regions.

North American Tropics. Rocky Mountain Forests. Pacific Coast Forests. "Dwarf Forests." See p. 1.

American Lumber Centers. Maine. New York. Pennsylvania. Lake States. Northwest and South.

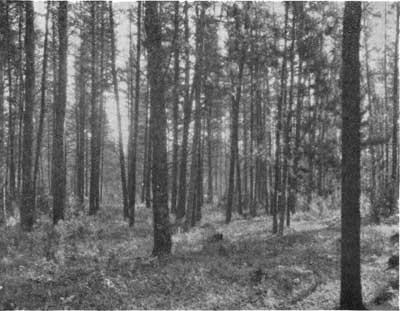

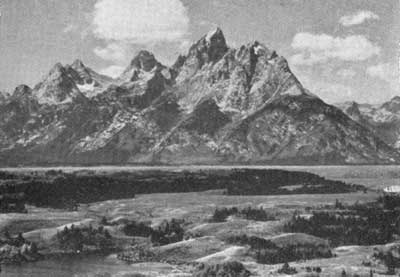

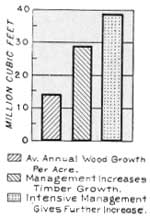

Timber growth responds to good management on the national forests. | |

|

AGENCIES WORKING FOR CONSERVATION |

||

|

THE UNITED STATES FOREST SERVICE History: The largest organization for forest conservation and development in the United States is the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture. The Forest Service is a direct outgrowth of an act, passed by Congress on August 16, 1876, authorizing an inquiry into the forest situation of the United States and the formulation of a forest policy. Dr. Franklin B. Hough was appointed Commissioner of Forestry to prepare this report. In 1877 an appropriation of $6,000 was made to secure further information and to make plans for a Division of Forestry. This Division, in the Department of Agriculture, was set up in 1881. That same year the Department sent a man to investigate European forestry methods which might be applied to American conditions. The Division of Forestry slowly expanded as a clearing house for forest statistics and information, but no practical administrative work was done until Congress, in 1891, empowered the President to set aside forest reserves from the public domain. President Harrison immediately established the Yellowstone Park reserve. Under Presidents Harrison and Cleveland about 40 million acres of reserves were created in the West. These reserves were held by the Department of the Interior and were administered by the General Land Office—the Division of Forestry merely being a technical advisory board. In 1898 the Division of Forestry interested some few private forest owners in forestry, and offered advice and plans to those willing to undertake forestry practices. The Division was given a nominal promotion, in 1901, when it became the Bureau of Forestry. Congress, urged by President Theodore Roosevelt, transferred the forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture in 1905. The Bureau of Forestry was renamed the Forest Service, and in 1907 the reserves became "national forests." Between 1901 and 1909 President Roosevelt, cooperating with Gifford Pinchot, the forester, added more than 148 million acres to the national forests. Smaller additions have been made since that time, and much land valued for resources other than timber has been removed from the national forests to be supervised by other agencies. The present area is more than 162 millions acres. In March 1911, Congress enacted what is popularly known as the Weeks law to protect navigable streams through the maintenance of forest cover on their watersheds. It provided for the cooperation of the Federal and State Governments in fire protection and enabled the Federal Government to purchase and acquire watershed lands. The purchase and acquisition of lands under the Weeks law was limited to the upper headwaters of navigable streams which the United States Geological Survey considered in need of forest cover and protection. Many important forest areas, particularly in the Lake States and in the South, could not be purchased or acquired under this act. In July 1924, therefore, the provisions were extended under the Clarke-McNary Act to include the entire country in a forest program of fire prevention, taxation study, State and Federal cooperation, assistance to private owners, and land acquisition and purchase. Administration: The national forest lands are administered by the Forest Service with headquarters in Washington, D. C. Ten regions with a regional forester in each (see map) have been set up to include all the States, Alaska, and Puerto Rico. These regions are divided into national forests, of which there are 145, averaging more than a million acres each. A forest supervisor is in charge of each of the national forests which are composed of two or more ranger districts administered by district rangers. Assistants are provided for these men as necessary to carry on the work of the forest. Numerous fire guards, lookout men, and other temporary workers are given seasonal employment each year. The policy of the Forest Service is one of forest use. Timber crops are raised to be harvested. Cattle, sheep, and horses range on the land best suited for grazing; recreational facilities are provided where there is a demand for them; and roads and trails are built to facilitate fire fighting and travel through the forest. Broad policies are established in the Washington and regional offices, but the practical forest administrative work is carried out in the forests and ranger districts. Each forest subdivision has problems peculiar to itself, and the ranger is better acquainted with these problems than are the higher executives hundreds or even thousands of miles away. Hence, the man in the field has considerable freedom in taking action that will better his forest and insure permanence and stability. In an organization where so much responsibility is vested in one man or small group of men, it is essential that only the most efficient foresters be employed—men whose interest in the public welfare transcends any private or personal aims. All permanent employees of the service are, therefore, under civil-service classification, and their work is subjected to frequent critical inspection. The ranger's job is to administer the forestry work of his district. If he is stationed in a grazing country, he supervises the entry and movement of all livestock—making sure that the range is not overgrazed and at the same time allowing sufficient entries to utilize all its forage possibilities. In a timbered area, he regulates timber sales, marking trees to be cut, and leaving enough young growth and seed trees to regenerate the stand. He enforces brush disposal measures to guard against fire, supervises seed collection, nursery work, and planting operations. He secures cooperation of local residents for forest protection and fire suppression; builds roads, trails, and telephone lines, and manages innumerable other projects that increase the value and utility of his district. Through this organization the forests of the United States are being regulated to help supply the country's enormous wood demands, to grow timber for future wood needs, and to provide a maximum of forest influences and values. State and private forest administrators are assisted by the Forest Service in planning, fire prevention, and reforestation. THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE The National Park Service was first authorized by President Wilson in August 1916, and the following year funds were appropriated for its establishment. For many years prior to that time, however, several national parks had been in existence—Yellowstone Park being established in 1872. Although the national parks are areas preserved for scenic value, historical significance, and natural phenomena, there are many acres of forest land included within their boundaries. Unlike the national forests, the parks do not permit the commercial utilization of timber or forage. Timber is cut only when necessary to suppress insect or disease infestations that might spread over great areas. The forested areas in the national parks are set aside as natural museums of original conditions, somewhat similar to the primitive areas of the national forests. The big trees in Sequoia and General Grant National Parks will never be cut down, but will remain as remnants of the original, giant forests of the West. The forests of Yellowstone will serve to enhance the unique scenery of the geyser area. The term "park" leads many people to think of the national parks primarily as recreational areas. One of the chief purposes of these holdings, according to Dr. John C. Merriam of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, is "that fundamental education which concerns real appreciation of nature."

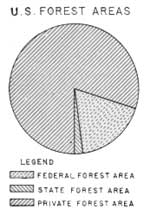

In the parks are more than 4-1/2 million acres of forest which add scenic touches to other natural phenomena, and which, although not serving to augment the timber supply, afford watershed protection and other forest influences. A trained, efficient personnel has been set up consisting of foresters, naturalists, botanists, geologists, and administrative executives. Their activities include research, education, protection, and park administration. THE SOIL CONSERVATION SERVICE In recent years the problem of soil conservation has assumed major proportions, and much valuable work has been accomplished to save agricultural and forest lands from the forces of soil erosion and to prevent stream silting. Soil erosion occurs on sloping or hilly land where rapid run-off of rain and snow water gouges gullies or pares off sheets of topsoil. Where winds have access to loose, unprotected soil, a process known as wind erosion—resulting in dust storms—takes place. To acquaint landowners with methods of combating soil erosion, and to preserve valuable public and private lands, the Soil Conservation Service has been established in the Department of Agriculture. A Forestry Division has been created in the Service to apply forest knowledge to the varying erosion problems. Much land that is now devoted to agriculture is too steep for that purpose. It will support crops for but a few years (5 to 10 is the average) before it erodes so badly that farming becomes impossible. Farmers are being taught to plant trees on such sites, and to concentrate their cultivating activities on more level land or on land that may be protected by simple terracing. Where large gullies have been eroded, terraces, small dams, and other obstructions are thrown up to retard the rapidly running water. Trees are planted in the gullies and on their banks to hold the soil in place. In places where wind erosion takes place, protective shelterbelts or windbreaks of trees are planted. These screens of trees on the windward side of a field reduce the wind velocity and thus tend to keep the fine topsoil on the fields. Besides decreasing soil erosion, windbreaks form favorable habitat for insectivorous and song birds that aid the farmer in controlling pests. Foresters with the Soil Conservation Service make surveys for planting and timber harvest, supervise planting, conduct forest research, and educate landowners to better forestry practice that will prevent erosion. Most of the actual fieldwork is being carried on by CCC camps, Transient bureaus, and relief organizations in cooperation with landowners. INDIAN FORESTS In the Department of the Interior, a Bureau of Indian Affairs was established in 1824 to supervise the care and education of the Government's wards, the American Indians. Today there are some 360,000 Indians in the United States, many of whom have been assimilated in the business, industrial, and professional activities of the white man. Most of them, however, are situated on the 200 reservations that have been set aside for them in 26 States. Much of the reservation land is worthless for agriculture, but of this nonagricultural land, about 7-1/2 million acres of commercial forest lands have been included in the Indian territories. Of this area, about 5 million acres is under sustained-yield forest management. Timber on these areas is cut according to forestry principles, and the land is maintained in a productive condition. Range management plans are in effect on the grazing areas, watershed protection is being improved through reforestation and erosion control, and fire prevention and suppression are being perfected. TREE PEST CONTROL The control of tree pests (insects and diseases) is an important phase of forest conservation. Although foresters may never eradicate completely all diseases and insects that attack trees, their attacks can be controlled so that epidemics or widespread infestations will not occur. Pest-control work of some sort is carried on by all forestry organizations. A large contributing factor in this line of forest protection and timber stand improvement is the work of the Bureau of Plant Industry and the Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine in the Department of Agriculture. These two organizations, cooperating with the various forestry services, carry on research, conduct field operations, and establish plant quarantines to stem the movement and development of pest attacks. Some of the major problems to which they have applied their facilities and experts are white-pine blister rust, brown-tail moth, gipsy moth, and satin moth. STATE FORESTRY State forestry had its beginning in 1885 when California, New York, Ohio, and Colorado established commissions or boards to regulate and conserve forest resources. All States now have some provision for forestry. There are a number of ways in which States can accomplish much toward the furtherance of sound forestry principles. The bulk of the commercial forest land in the United States, about 80 percent, is in private ownership. State forestry organizations are in a position to help maintain the productivity of these areas by: (1) Portraying the advantages of forestry methods through demonstration forests; (2) offering adequate fire protection; (3) giving advice and technical aid; (4) distributing trees for reforestation; (5) establishing forests on tax-delinquent, cut-over land; (6) passing and enforcing laws relating to sane cutting practices; (7) creating forest taxation policies that recognize timber as a long-term crop; (8) carrying on research projects in forestry and forest products; and (9) educating the public to an appreciation of forest values. The area of State forests is comparatively small—4-1/2 million acres—of which about 75 per cent is in Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Michigan. About 1 million acres is under timber management plans.

Fire protection is by far the greatest contribution that the States now offer, although all but three States give aid and advice to private forest owners, and many aid by distributing trees for reforestation. Very little has been accomplished by the States in the form of forest research, except at forest schools. Of the 25 collegiate forest schools in the country, all but three are operated by the States. Forest parks, of which there are more than 2,700,000 acres, afford recreational opportunities and in this way stimulate forest appreciation and interest. In 1931, there were 50,000,000 recreational visitors in the State forests and parks. New York, with large park reserves in the Catskills and Adirondacks, maintains four-fifths of the State park area. In addition to the classified forests and parks, there are more than 6 million acres of forest land owned by the States, but which have no specific designation. Most of these areas, however, receive protection from fire, and are under some timber-cutting regulations. Within the States are smaller political units—counties, municipalities, and towns—that own approximately 1 million acres. Although the State holdings, as a whole, are relatively small at present, there is a likelihood that State forests and parks will increase in area. Much abandoned, tax-delinquent land is reverting to State ownership. Many States are purchasing additional areas; and recreation, particularly forest recreation, is growing in importance. State governments are better situated to stimulate and enforce sound forest practices than is the Federal Government or any other agency. |

Forest Inquiry, 1876. Forestry Commission, 1877. Division of Forestry, 1881. Division Reserves Authorized, 1891. Work of Presidents Harrison and Cleveland. Private Forest Owners Aided, 1898. Bureau of Forestry, 1901. Reserves Transferred from Department of Interior to Department of Agriculture, 1905. Forest Service and National Forests, 1907. Work of Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot, 1901-09. 162,000,000 Acres. Federal and State Cooperation under Weeks Law, 1911. Weeks Law Extended by Clarke-McNary Act, 1924.

10 Forest Regions. 145 National Forests.

Many Workers. Forestry Means Use. Central Office Links Field Activities. The Ranger's Responsibility. Efficiency Demanded. The Ranger's Job. A Thousand Jobs.

Saving Superlative Sites.

Fundamental Nature Education. The national parks preserve areas of great scenic value. Forests for Education, Recreation, Influences.

See pp. 104, 205. The Forester's Job. Government Indian Policy.

Forest Conservation on Indian Reservations. See pp. 87, 94. Keeping Trees Healthy.

From a Small Beginning to a National Policy. How States Can Promote Forestry.

A popular poster.

State Forest Parks.

State Holdings increasing. | |

|

Governmental departments and legislation are inadequate, in themselves, to cope with the problems of forest preservation and the maintenance and use of forest values and influences. Regulations that do not have public backing are of little effect. The forestry movement in the United States has not been lacking in ardent supporters. Each year thousands of public-spirited citizens are added to the rolls of forestry and conservation groups. NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS Chief among the Nation-wide groups to stimulate public interest in forestry are The American Forestry Association, The Society of American Foresters, The American Tree Association, and the Association of State Foresters.

The oldest forestry organization of national scope is The American Forestry Association, founded in 1875. From a small beginning, it has grown to be a major influence in popularizing the advantages of forest regulation and protection. Its magazine, American Forests, presents forestry and conservation articles in popular form and is widely read throughout the United States. Foresters in North America have grouped themselves together in the Society of American Foresters. Founded in 1900, the society has grown to include more than 3,700 members. The Journal of Forestry, its official organ, is the only technical forestry magazine in the country. It is world-wide in scope, and through its pages about three thousand foresters are advised of forestry progress, research, and policy trends. In the United States, the society has played a large part in influencing forest legislation, administrative policies, and public sentiment. "To further forest protection and extension and to increase appreciation of forests as natural resources essential to the sound economic future of the country," the American Tree Association was founded in 1922. The association has done much to popularize forestry among the general public and has instituted the teaching of forest appreciation to school children. It publishes The Forestry News Digest, a review of timely and significant forestry information. More than 4 million copies of the association's Forestry Primer have brought pertinent forestry facts to the public eye. Numerous other publications have been distributed to schools. Since 1924, four editions of the Forestry Almanac, a book containing articles on the history and accomplishments of all American organizations working for forest conservation and use, have been issued. The association cooperates with schools, colleges, service clubs, and patriotic groups in the spread of forest knowledge. Since 1920 an important force in interstate forestry cooperation has been the Association of State Foresters. This organization formulates broad policies for State forest management, and discusses legislative changes for better forest regulation. OTHER ORGANIZATIONS Groups of foresters and others interested in forestry have been formed in certain sections of the United States to further forestry practices in their respective regions. Their problems are regional in scope and are more closely defined than those of the national organizations. Within the States are 47 State, county, municipal, or sectional groups alined in the interest of forestry. With varying names—committees, chambers, associations, clubs, councils, societies, institutes, and conferences—these organizations operate for the same general aims: Fire prevention and suppression, reforestation, forest education, wise use of forest products, legislation, and forest regulations. Such groups stimulate forestry and conservation. FORESTRY ON PRIVATE LANDS Inasmuch as nearly 400 million acres of commercial forest land, or about 80 percent of the total, is privately owned, it is readily apparent that if forests of the United States are to remain productive it is up to private owners to practice forestry. LARGE HOLDINGS Private forestry, particularly on the 270 million acres of industrial holdings, has many drawbacks. Wood crops, unlike mushrooms, do not spring up over night, nor do they mature in one season as do corn or potatoes. The man who plants trees must look ahead 30 to 50 years for even a short rotation crop of saw timber. In that time he pays taxes on the trees and land, protects his forest from fire, diseases, and insects; conducts cultural operations (which may not pay a profit); and when the crop is finally ready for harvest, a market must be found or developed. It is not hard to appreciate the lumberman's viewpoint when he adopts the policy of "cut out and get out." A great demand for timber has spurred operators on to immediate profits. They cut all the timber, then the cut-over land is allowed to revert to the State for nonpayment of taxes, and the lumbermen move on to more profitable areas. This practice has been followed in the cutting of virgin stands of mature timber.

The depletion of practically all large tracts of virgin timber has caused lumbermen in recent years to look for merchantable second growth. This can be found only where forests have sprung up after cutting or where early efforts were made to leave the younger trees for a second crop. The lumberman is beginning to realize, as areas of big timber become scarce, that careful logging methods and fire prevention are necessary if woods operations are to be sustained. Many owners and operators are instituting practices whereby trees are cut to certain diameter limits, or sufficient young trees are permitted to remain and grow for future crops. Some owners have divided their forests into cutting circles or blocks, which are cut periodically and on which provision ts made for successive harvests. Pulpwood forests are especially adaptable to private forestry practices, because of the comparatively short period required to grow wood to pulpwood size. With the ever changing uses of wood, there is an increasing demand for products that can be derived from trees much smaller than those of early lumber days. Many new uses have been developed for cellulose; and cellulose (the basic material of woody plants) may be extracted from small trees. Sustained-yield forestry insures perpetual crops from the forest. Now that all giant timber has been cut, except in isolated stands, owners have turned to forestry whereby large lumber businesses comparable to other large industries may be developed. Timber culture supplies the basis for enterprises that will last for generations—not a "cut out and get out" system—as there are few stands to which the lumberman may now turn. The enlightened owner practices forestry, cuts a crop each year, and leaves enough young trees growing that he may return for successive crops. The tax problem: One of the chief drawbacks to forest practice on private land has been the tax problem. Tax assessors, in the past, have not regarded timber as a crop, but have placed a taxable value on the land each year. Over a relatively short period of time, the taxes paid on a forest tract exceed the income from the final crops. Many States have reduced this difficulty through sane forest taxation whereby a nominal sum is charged each year, and a heavier tax is placed on the final yield. Public and private cooperation: Privately owned forests, with few exceptions, are regarded by the public as free hiking, hunting, and picnicking grounds. Although forest owners, as a rule, have no objection to such use of their land, they realize that every person entering the forest is a potential fire setter (either carelessly or maliciously). Some few owners have organized fire-fighting forces to reduce this danger; but this expense coupled with taxes creates a cost burden greater than the average forest can bear. States could extend their fire-control systems to include such areas of private land, the same as city fire departments serve the homes of their citizens. A State forest fire organization that protects State-owned land only is like a city fire department that confines its protection to the city hall and post office. The destruction of 10,000 acres of privately owned forest land means just as much to the State as the burning of an equal area of State forest. Although the profit realized at a timber sale goes to the owner, climatic influences, recreational opportunities, and abundance of timber benefit the general public much more than they do the owner. The State should share the tax and fire protection burden on lands of common benefit. Forestry on private forest land is something to be accomplished through State and private cooperation. The landowner must be encouraged to practice forestry, but such encouragement should be in the form of reduced taxes and adequate protection, as well as in technical advice. The public has a choice between aiding the timberland owner in forestry practices, or receiving a vast amount of cut-over, burned-over, tax-delinquent land in the future. FARM WOODLANDS More than 185 million acres of forest land is in farm woods. These areas are particularly adaptable to forestry practice on a small scale. The farm woodland is capable of yielding fuel, fence posts, poles, and saw timber for repairs and farm construction. In addition, many farms sell wood as a cash crop. Farm woods comprise about one-third of the Nation's commercial forest land. Most of them (95 percent) are in the East where they occur as small holdings separated by cultivated fields or meadows. Protection from fire and insect attack, therefore, is a simpler matter in farm woods than in larger industrial holdings. Constituting part of the farm area, they are relatively easy to manage, as no additional expense is incurred because of them, and they may be worked in seasons when farming is at a standstill. In many States farmers received trees free or at low cost for reforestation. Advice as to proper trees for different sites, the best planting methods, and other forestry practices is freely given. Colleges and universities aid the farmer through agricultural extension in forestry. Studies are made to find uses for woodland products, and in some States cutting and saw mill practices are taught to farmers' clubs and associations. It is believed that the average farm wood lot is in better growing condition than most other privately owned forest land. The farmer can practice selection cutting and thus keep his woodland producing indefinitely. Although the woods on one farm rarely is capable of satisfying great demands, the total farm woodland acreage supplements many local markets and fills the domestic needs of the farmers. In the South, farm woods are important to the naval stores industry; and most of the country's maple sugar is secured from wood lots in the Northeast. |

Society of American Foresters.

American Tree Association.

Educating the Public. Association of State Foresters. The Movement Grows. No Matter What You Call It.

Trees Not Like Mushrooms. Narrow Margin of Profit.

Pulpwood—A Good Private Venture. Growing Successive Tree Crops. Taxes Grow Faster Than Trees.

The Private Owner Helps the State. The State Should Help the Private Owner.

Aid for Farmer Foresters.

| |

|

SUMMARY |

||

|

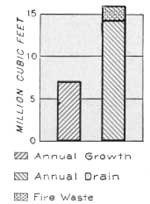

Despite early 1900 prophesies of a timber famine we still have about 495 million acres of commercial forest land in the United States; more than 10 million acres of forests removed from commercial use and dedicated to use as parks, monuments, reservations, and preserves; about 108 million acres of noncommercial forest land; and from 54 to 55 million acres of abandoned farm lands. This totals nearly 670 million acres on which forest products might be grown for American use. The 10 million acres in parks and similar areas probably will not be used for timber production, but will remain as recreational areas and outdoor museums. The same natural regions of forest growth that were on the continent when the settlers landed still exist, but the characters of the stands have changed. Old growth or virgin timber now occupies only 20 percent of the forest area, and 75 percent of this is in the Pacific coast and Rocky Mountain regions. Only 15 percent remains in the Southeast, and 13 percent in the entire Middle Atlantic, Lake States, Central, and New England regions. The best forest land is now in private ownership. If these areas are to supply American timber needs they will have to be put under forest management. Public forests are largely second-growth land which was acquired after the best timber had been taken out by private operators. Second-growth forests, upon which we must depend for future wood supplies, are increasing in area and number. Abandoned farm land of the submarginal class is being added to the potential forest resources. Based on present timber requirements it has been estimated that the forest land if put to intensive use will adequately supply the United States' wood requirements. Seven billion cubic feet of saw timber and cordwood is the estimated annual growth, but the drain is about 16 billion cubic feet. The annual drain includes about 1.8 billion cubic feet that is destroyed by fire, insects, diseases, and other causes. There are a number of factors, however, which will tend to balance growth with drain in the future. The annual drain may be decreased not by decreasing consumption, but by more efficient fire protection and more complete insect and disease control. Wood in use may be preserved from decay and fire by preventive treatments, and ways have been devised to secure more complete utilization of timber both in the woods and in the shop. Although substitutes have replaced wood in some uses, it is not thought that the importance and demand for wood will suffer appreciably. The total effects of all these measures will decrease the annual drain. Annual growth of forests is increasing because of the extension of forestry practices, and the reforesting of idle lands. Samuel T. Dana states that if our wood demands do not become greater they may be met by growing 29 cubic feet per acre each year on 496 million acres of forest land which now produces only 14 cubic feet per acre. It has been estimated that with crude forestry practices 39 cubic feet per acre may be expected. Intensive forestry will raise 61 cubic feet per acre per year. It is not uncommon to find second growth woodlands under management that produce a cord per acre each year. (Average 80-90 cubic feet.) To secure this growth-drain balance in the near future, much forest land now idle or growing in poor condition must be put under management. State and Federal organizations are practicing forestry as far as present appropriations will permit. When the effects of the Civilian Conservation Corps are felt, the picture may be somewhat different than at present. Some foresters believe that the CCC has advanced forestry 20 years. Coupled with this work on public land is the contribution of industrial forest owners and farmers on private land. Although the outlook for America's forests and products appears more encouraging than it did 30 years ago, we should not permit our interest and energy to lag. Much is yet to be done—practically and experimentally. Work that has been started must be maintained at a high degree of efficiency and with increasing intensity. |

Plenty of Forest Land Left. Location of Timber Limits Use.

Need for Management.

Balancing Growth and Drain.

See p. 162.

Putting Idle Land to Work. Work of CCC. Work Must Continue. | |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

ccc-forestry/chap3.htm Last Updated: 02-Apr-2009 |