|

City of Rocks

Historic Resources Study |

|

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE CITY OF ROCKS REGION

Introduction

History tells of 'Granite City' where the immigrant wagons rolled, indian massacres, rattling of stage coaches and of hidden gold. I wish to tell of the simple life and dreams of these settlers who came in around the year of 1910. Water was usually dug for by a shovel and it wasn't far from the surface; and the sage brush grew high and a horseman could ride through without being seen. [11]

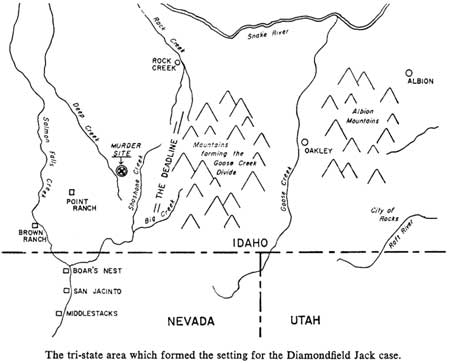

Distinct historic themes pertinent to the City of Rocks National Reserve include American Indian habitation, the fur trade, westward migration, the development of national and regional transportation networks, agricultural development, and recreation and tourism. Stories of conflict between Indians and newcomers, stagecoach bandits, and range wars represented fleeting moments in the history of the region. However, because they personify the Wild West, these events captured the imagination of local residents and of visitors, and stories thereof have been repeated and embellished accordingly. Overland migration was similarly fleeting, yet ultimately led to the settlement of the West, to homestead legislation, and to the growth of agricultural communities — the region's most consistent and long term land use in the post-settlement era.

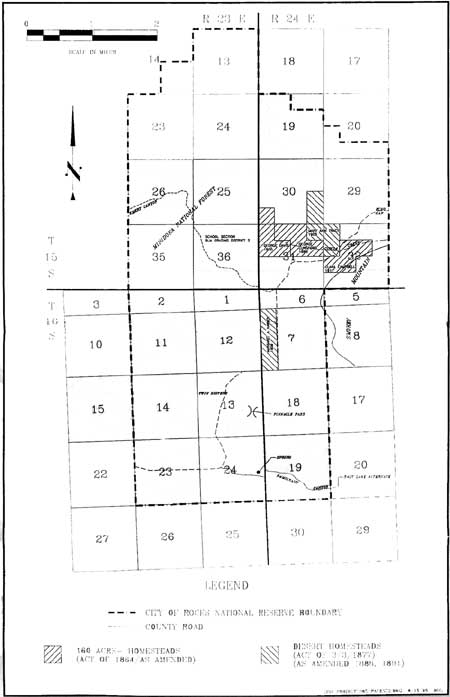

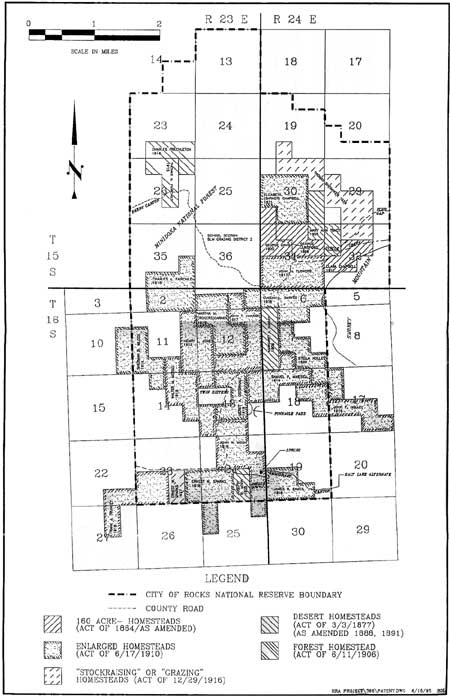

The local agricultural industry followed a progression witnessed throughout the semi-arid West. The early open-range cattle industry was devastated by the winter of 1889 and disrupted by the arrival of "wool growers" and farmers. Early (ca. 1880-1900) homesteaders laid claim to irrigable land in the valley bottoms; small-scale irrigated farming was supplemented with cattle or sheep ranching. Stock grazed during the summer months on public land and were pastured (and fed) throughout the winter on the home ranch. Later settlers were relegated to dryland and grazing tracts, patented under the terms of the Enlarged Homestead, Forest Homestead, or Stockraising Homestead acts. The regional drought beginning ca. 1917 and the depression of the 1920s and 1930s resulted in the whole-scale exodus of this later community. By the 1930s, recreational use of the "beautiful" but unwatered and unproductive land was seen as the logical economic alternative to farming.

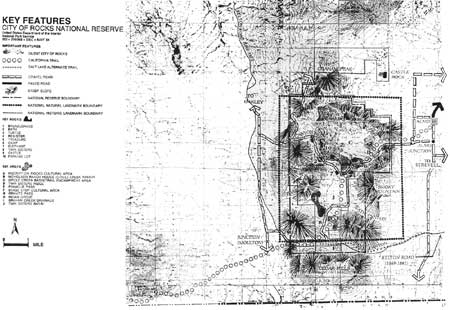

Three threads link all phases of area development: Water (or the lack thereof) brought the fur traders and the emigrants, and determined the physical characteristics and the success or failure of area farms. Transportation routes (or the lack thereof) have had a causative and resultant impact on the history of the region: the City of Rocks was at center stage of a phenomenal national emigration. Yet the transcontinental railroad and the interstate highway system — neither of which is dependent upon the presence of water, grass, or gentle grades — have passed the region by. The unique natural features of the region elicited extensive comment from westward emigrants. For those who settled and stayed, the City of Rocks has served as a community picnic ground, a point of geographic reference, and a cultural compass bearing on the importance of their community in the history of the nation and of the West (Figure 4).

|

| Figure 4. Key Features, City of Rocks National Reserve (map prepared by USDI, NPS, 1994). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The City of Rocks National Reserve occupies an area at the junction of two physiographic regions, the Great Basin and the Columbia Plateau, at the northern margin of what anthropologists call the Great Basin "culture area." The concept of culture area, as used by anthropologists for some time, is generally defined as a geographical area within which native inhabitants share similar cultural traits. Strengthening the concept of cultural relatedness within the Great Basin culture area is the fact that all but one of the extant native groups living within it speak "Numic" languages, a division of the Uto-Aztecan language family. [13]

Of course, people inhabiting the periphery of "culture areas" often display a blend of traits from adjacent areas. The Shoshone and Bannock people who occupied the upper Snake River Valley at the time of Euroamerican contact displayed a blend of cultural traits typically associated with Plains, Great Basin and Plateau cultures. "Just as the environment and resources of southern Idaho were varied and transitional to other physiographic areas, so also was the culture of the Shoshone and Bannock diverse." [14]

In September of 1776, Francisco Atanasio Dominquez and Silvestre Velez Escalante explored the region extending from Santa Fe to Utah Lake (near what is now Provo). Here they camped with the "Comanche" (Shoshone). [15] In 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition camped near Lemhi Pass with another Shoshone band. Lewis made extensive notes regarding the material culture and vocabulary of the Shoshone people that they encountered. Lewis' lack of comment on the presence of Bannock people has led to the assumption that the residential integration of Shoshone and Bannock people occurred during the later part of the 1800s.

The relationship of the Northern Shoshone and Bannock, observed by ethnographers during the first part of the 20th century, is described as follows:

The Fort Hall, or upper Snake River, Shoshone and Bannock formed into large composite bands of shifting composition and leadership. The Shoshone speakers were always the majority, but the chieftaincy was sometimes held by a Bannock. Most of the Fort Hall people formed into a single group each fall to hunt buffalo east of Bozeman, Montana, and returned to the Snake River bottomlands near Fort Hall for the winter. . . The large bands split into smaller units for spring salmon fishing below Shoshone Falls, and summer was spent digging camas roots in Camas Prairie and other favored places. Deer and elk were hunted in the mountains of southeastern Idaho and northern Utah. [16]

Because of its excellent grazing resources, pinion pine nuts, rock chucks and game animals, and vegetable roots, the upper Raft River and the City of Rocks served as a "Shoshoni seasonal village center" and summer range for the Shoshone's extensive horse herds. [17] Almo residents reported that as late as the 1970s,

The Indians [from the Fort Hall Reservation] used to come every fall gathering pine nuts. They would gather the cones all day, then dig huge pits, fill them with wood and set it on fire. Then when the coals were right, they put the sticky cones in and covered them with dirt. By morning the cones would be popped open. The squaws picked the nuts out of the cones. They would sell them for .25 a pint. . . . every year, 'til the last few years, they come and traded back and forth with people for hides and on the years that the pine nuts were good.... they come by car. Then they first come, they come in a buggy and team, wagon and team. And camp here, they'd have a camp right here, right above here for weeks at a time. . . They'd come here and buy deer hides... They trades us buckskin gloves for deer hides. See and then they make the gloves out of the deer hides. [18]

Years after their consolidation on the government reserve at Fort Hall, the Bannock-Shoshone would return for "ceremonial dances. Their camp grounds were near the Twin Sisters as there was a spring of cold running water close by." [19] Non-Indian settlers also report an "Indian legend" centered at the City of Rocks, namely that "a bath in [Bathtub Rock] before sunrise will restore youth to the aged." [20] Evidence of the city's traditional significance thus continued long after ranching enterprises had transformed the area. [21]

Fur Trade and Exploration

I got safe home from the Snake Cuntre... and when that Cuntre will see me again the Beaver will have Gould skin. [22]

The Raft River Valley formed an important transportation link between the heavily trapped Snake and Bear rivers. Between 1820 and 1830, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) also heavily trapped the Raft River, as part of their general policy to decimate beaver populations in the area of joint British/American occupation established in 1818. Despite this proximity, City of Rocks was not the focus of the trappers' attention and is neither described nor mentioned in passing in the trappers accounts.

In 1811 an expedition of the Pacific Fur Company, led by Wilson Price Hunt and Donald Mackenzie, traveled down the Snake River, past its confluence with the Raft River, enroute to their new Pacific coast trading post at Astoria. Although Mackenzie was convinced that the Snake country's beaver population was considerable, the difficulty of that 1811 journey discouraged further exploration of the Snake River and its tributaries until 1818. [23]

In that year, Mackenzie, a new partner in the nascent North West Company, led the first "Snake Country Brigade" into an area extending from Fort Nez Perce south as far as the Green River and east as far as the Bear River. By 1820, Mackenzie had established a system of mobile trapping and summer rendezvous that incorporated the Upper Raft River region, near the City of Rocks. Subsequent incursions into this heretofore unexplored region were made by the Hudson Bay Company's Finian McDonald and Micel Bourdon in 1823, whose trapping grounds included the Upper Raft River and tributary creeks and by the HBC's Alexander Ross, whose brigade camped near the City of Rocks in 1824. (Ross did not proceed beyond this camp, noting a negative cost-benefit ratio to further trapping in the rugged country. Despite his proximity to the City of Rocks, and his keen interest in geography, Ross failed to mention the city in his diary, suggesting that he had neither seen nor heard of the geographic oddity.) [24]

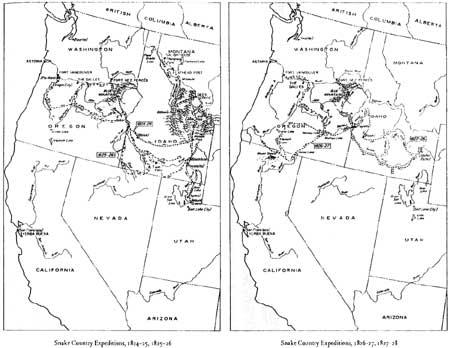

Peter Skene Ogden assumed control of Ross' Snake brigade in 1824, at a time when competition from American trappers lent incentive to further exploration of the Raft River's tributaries. (His brigade of 1825 consisted of "fifty-eight men who were equipped with 61 guns, 268 horses, and 352 traps as well as a number of women and children, families of some of the freemen who were always part of such expeditions.") In 1826, Ogden's party discovered Granite Pass; their westward journey to the pass would have placed them very near the City of Rocks. Ogden's successor John Work also explored the Goose Creek country between Junction Valley and Granite Pass yet also did not pass through the City, or failed to describe it. By 1832, Work concluded that the region immediately west of the Raft River "lacked enough beaver to justify further attention (Figure 5)." [25]

Like the emigrants that would follow them, fur traders did not travel through the region uncontested: service with the Snake River Brigade was considered "the most hazardous and disagreeable office in the Indian country." During Finian McDonald and Micel Bourdon's 1823 Snake River expedition, Bourdon and five others were killed. Upon his return, McDonald wrote "I got safe home from the Snake Cuntre... and when that Cuntre will see me again the Beaver will have Gould skin." [26]

Although the fur trade had no immediate effect upon the City of Rocks, geographical discoveries made during that era had an important and lasting effect on the region. For over thirty years, in search of beaver, glory, adventure, and a watered transportation route to the Pacific, the great men of the trapping and exploration era [27] searched for a mythical Buenaventura River draining the country west of South Pass to the Pacific Ocean. The search was daunting, hindered by the extremely complicated drainage system west of South Pass. The Green, the Big Gray, the Salt, the Sweetwater, and the Bear rivers all head near South Pass. The Green flows into the Colorado, bound for the Gulf of California. The Big Gray and Salt feed the Snake, thence the Columbia, and finally the Pacific. The Sweetwater is part of the Platte-Missouri river system, and flows into the Gulf of Mexico. The Bear River flows north northwest as far as Soda Springs, where it makes an abrupt turn south to the Great Salt Lake. The lake has no outlet. [28]

Trappers and explorers focused their search for the Buenaventura on the alkaline plains west of the Great Salt Lake, south of the City of Rocks, and across which the first overland emigrants to California would pass. They would find this "a terrible country, a sandy waste men ventured upon at the peril of their lives... Even springs were scant, and likely to be bitter with salt. There were no beaver there — no riches." [29] And there was no Buenaventura:

There was no great river, there was no broad water highway to the Pacific. The drainage from the Rocky Mountains went south and north and east but not west, except for those streams like the Weber and the Bear, which ran ineffectually into the Dead Sea, and the Humboldt, which died with an alkaline whimper in the Humboldt Sink. [30]

Ogden's Snake River Brigade of 1829 discovered the Humboldt River. Although they did not know it, and although the search for the Buenaventura would not be officially conceded until 1843, this was the "lost river": a small stream with brackish water of vile taste that sank "with an alkaline whimper." Future travelers — the hundreds of thousands of emigrants bound for California — would also curse the Humboldt, while relying absolutely on its alkaline water and sparse forage, the only water, the only grass, the only refuge, in an enormous expanse of desert. [31]

Ogden was similarly unimpressed by his 1825 discovery of Granite Pass. For Ogden, the discovery was relatively inconsequential; the Goose Creek drainage was not a significant source of beaver, and fur trappers, unlike later emigrants, were not restricted in their travels to routes wide enough for wagon passage and possessing sufficient feed and water for wagon stock.

In 1833, the American Fur Company's Captain Benjamin L. E. Bonneville retained Joseph Reddeford Walker to lead a band of trappers west from Salt Lake in search of new trapping grounds. Traveling west, Walker forged a trail across what became known as the Bonneville Flats. (Six years earlier, Jedediah Smith had almost died on this passage, as would the first overland migrants to California, eight years later.) Walker traveled north of this route on his return in 1834, descending Goose Creek to the Snake River. From this vantage point, he "rediscovered" Granite Pass. In 1842, Joseph B. Chiles traveled east across the pass, and confirmed its potential as a possible, although difficult, route to the Humboldt. Granite Pass would provide the final link in an overland route between Illinois and the Sacramento Valley: the California Trail, as it ran through the City of Rocks. [32]

Overland Migration

In 1840, Thomas Farnham and his small party traveled from Peoria, Illinois to the Oregon Territory, initiating a mass migration that would peak at over 100,000 in 1852 but that would not end until completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Historian John D. Unruh, Jr. wrote that overland migration has been "one of the most fascinating topics for writers, folklorists, and historians of the American West. The overlanders'. . . legendary covered wagons have come to symbolize America's westward movement." [33] The emigrants themselves realized the enormous personal, social, cultural, and political consequences of their journey and left an astonishing array of diaries and letters describing their routes and life along those routes. Chimney Rock, Independence Rock, and the City of Rocks figure prominently in these accounts — they disrupted the monotony of the journey as surely as they broke the level surface of the plains. In varied degrees of eloquence and imagination, emigrants duly described them. The City of Rocks also occasioned comment as a place of heightened Indian menace; a place of final respite, prior to the dreaded crossing of the barren Humboldt plain; and as an important trail junction.

All migrations are a response to both "push" and "pull" factors. Depression hit the vast Mississippi Valley in 1837. Land and opportunity that only twenty years earlier had represented the American frontier were scarce. Wheat sold for ten cents a bushel, corn for nothing, "and bacon was so cheap that steamboats used it for fuel." [34] The push west then, for this "free, enlightened, [but] redundant people," was considerable. [35]

|

"Come along, come along — don't be alarmed, Uncle Sam is rich enough to give us all a farm." 1852 camp song, quoted in John Mack

Faragher, Women and Men on the Overland Trail, (New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1979), p. 17.

|

The pull was also compelling: the opportunity to secure the Oregon Country as American territory and unlimited, fertile soil, not only in Oregon but also in Mexico's northern province of California.

The pull had begun decades earlier, in print if not in fact. In 1813, the St. Louis Missouri Gazette reported "no obstruction . . . that any person would dare to call a mountain" between St. Louis and the Columbia River [and] in all probability [no Indians] to interrupt . . . progress." [36] In 1830, trapper William L. Sublette successfully breached the Continental Divide at South Pass (Wyoming) with wagons. He subsequently reported to the Secretary of War that "the ease and safety with which it was done prove the facility of communicating over land with the Pacific ocean." [37]

One year later, Boston's American Society for Encouraging the Settlement of the Oregon Territory published a General Circular to all Persons of Good Character Who Wish to Emigrate to the OREGON TERRITORY. The circular promised an account of "the character and advantages of the country; the right and the means of operations by which it is to be settled and ALL NECESSARY DIRECTIONS FOR BECOMING AN EMIGRANT." [38]

|

Emigrants commonly employed a 2,000- to 2,500-pound farm wagon with a flat bed.... A wagon of this size loaded with some 2,500 pounds required a team of six mules or more commonly four yoke of oxen... The provisions for the entire trip and all the baggage would have to conform to the weight limitations of the team... A family of four could make the trip in a single wagon... but because of their size, the majority of families were compelled to take more than one wagon. [Faragher, Women and Men on the

Overland Trail, pp. 20-22.]

|

Others urged caution, arguing that while the mountains might be passable (with great difficulty), the "Great American Desert" was not. W. J. Snelling predicted mass starvation in the arid plains, loss of stock to Indian theft, and Indian attack "in retaliation for the pillaging of white hunters." He concluded that the trip could not be made in one season, forcing emigrants to winter in the Rocky Mountains, where they could first eat their horses and then their shoes, before "starving with the wolves." Potential emigrants debated the wisdom of the journey in this carnival of "ignorance, unreality and confusion." [39]

In compelling proof of the journey's possibility, Presbyterian missionaries Samuel Parker, Marcus Whitman, and Henry Spaulding, in the company of women and children, traveled overland to Oregon Territory in 1834. Methodist Missionary Jason Lee followed in 1839, with 51 settlers. These men and women went west as evangelists, not to prosper but to save the souls of the native inhabitants. Yet, western historian Ray Allen Billington writes that "their contribution to history was significant, not as apostles of Christianity, but as promoters of migration. More than any other group they kept alive the spark of interest in Oregon and hurried the westward surge of population into the Willamette Valley." Reports sent from the Whitman mission to eastern religious journals were replete with details of the prospering farms, of abundant resources, and of virgin land. Perhaps as significantly, the Whitman's presence promised shelter and companionship at the end of a long and unfamiliar trail. [40]

California boosters also described a gentle and healthy climate, potential agricultural wealth, an enormous variety of resources, and abundant game. [41] In 1840, Richard H. Dana published Two Years Before the Mast, "probably the most influential single bit of California propaganda." Dana boasted "In the hands of an enterprising people, what a country this might be!" And an enterprising people responded. [42]

The first party to travel overland to California hailed from Platte County, western Missouri. The 69 men, women, and children were encouraged by returned trapper Antoine Robidoux who described a "perfect paradise, a perennial spring." [43] They were led by John Bidwell and John Bartleson and further assisted by trapper Thomas Fitzpatrick and Jesuit priest Father De Smet. (Bidwell recalled years later that "our ignorance of the route was complete. We knew that California lay west, and that was the extent of our knowledge.") [44] Like the parties to follow, they raced the seasons, scouting the Platte River plain for the first sign of sufficient spring grass to sustain their herds, and sprinting across country at an average pace of 15 miles per day in a desperate race to beat the snow to the Sierra Nevada (Figure 6).

The Bidwell-Bartleson party followed the Oregon Trail as far as Soda Springs (near present day Pocatello, Idaho). Here, half the party opted for Oregon. The remainder abandoned their wagons and proceeded southwest across the tortuous, alkali "Bonneville Flats" north of the Great Salt Lake, along the trail blazed — and dismissed — by Jedediah Smith in 1827 and Joseph Walker in 1833. [45]

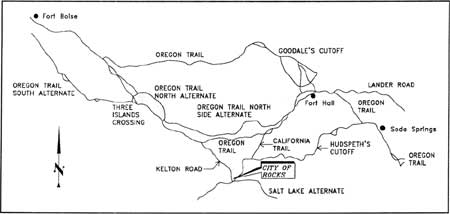

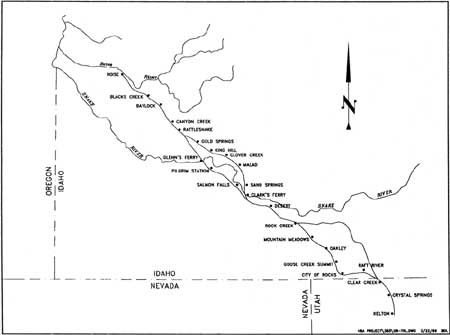

Other parties followed by alternative routes: via Santa Fe, via Oregon, and, in 1843, via City of Rocks/Granite Pass, by way of the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall. This later party traveled under the leadership of Walker and of Joseph B. Chiles, a member of the Bidwell-Bartleson party of 1841. At the confluence of the Raft and Snake rivers, Chiles and "a few companions" proceeded west along the Snake, to the Malheur River, and thence south to California. Walker and the remainder of the party proceeded up the Raft River, to the City of Rocks, west to the Goose Creek range, to a (barely) tolerable wagon crossing at Granite Pass — a route destined to become the main overland road to California.

This route met the basic requirements of an overland trail: it possessed a minimum of geographic obstacles (although wagons had to be lowered by rope down Granite Pass and other defiles); water was available at reasonably regular intervals, as was sufficient browse for emigrant stock; and, with the exception of the unfortunate and much-lamented loop to the north between South Pass and the Raft River confluence, the trail formed a direct line between the Mississippi Valley and the promised land. [46]

Subsequent alternatives — the Applegate Trail, the Salt Lake Alternate, Hudspeth's Cutoff — varied the route between South Pass and the Upper Humboldt, but all funneled to City of Rocks and Granite Pass. These alternates promised varied advantages: some were billed as shorter, offering emigrants the advantage of time (winter and the Sierras approached); some offered access to provisions (the barren Forty-Mile Desert, within which both man and beast had starved, approached). The advantages realized did not always comport with those promised: shorter did not always mean faster and provisions were not always available. [47]

|

Bound for California Monday, April 9th, 1848. I am the first one up; breakfast is over; our wagon is backed up to the steps; we will load at the hind end and shove the things in front. The first thing is a big box that will just fit in the wagon bed. That will have the bacon, salt, and various other things; then it will be covered with a cover made of light boards nailed on two pieces of inch plank about three inches wide. This will serve as for a table, there is a hole in each corner and we have sticks sharpened at one end so they will stick in the ground and we will have a nice table; then when it is on the box George will site on it and let his feet hang over and drive the team. It is as high as the wagon bed. Now we will put in the old chest that is packed with our clothes and things we will want to wear and use on the way. The till is the medicine chest; then there will be cleats fastened to the bottom of the wagon bed to keep things from slipping out of place. Now there is a vacant place clear across that will be large enough to set a chair; will set it with the back against the side of the wagon bed; there I will ride. On the other side will be a vacancy where little Jessie can play. He has a few toys and some marbles and some sticks for whip stocks, some blocks for oxen and I tie a string on the stick and he uses my work basket for a covered wagon and plays going to Oregon. He never seems to get cross or tired. The next thing is a box as high as the chest that is packed with a few dishes and things we don't need til we get thru. And now we will put in the long sacks of flour and other things... Now comes the groceries. We will made a wall of smaller sacks stood on end; dried apples and peaches, beans, rice, sugar and coffee, the latter being in the green state. We will brown it in a skillet as we want to use it. Everything must be put in strong bags; no paper wrappings for this trip. There is a corner left for the wash-tub and the lunch basket will just fit in the tub. The dishes we want to use will all be in the basket. I am going to start with good earthen dishes and if they get broken have tin ones to take their place. Have made 4 nice little table cloths so am going to live just like I was at home. Now we will fill the other corner with pick-ups. The iron-ware that I will want to use every day will go in a box on the hind end of the wagon like a feed box. Now we are all loaded but the bed. I wanted to put it in and sleep out but George said I wouldn't rest any so I will level up the sacks with some extra bedding, then there is a side of sole leather that will go on first, then two comforts and we will have a good enough bed for anyone to sleep on. At night I will turn my chair down to make the bed a little longer so now all we have to do in the morning is put in the bed and make some coffee and roll out. The wagon looks so nice, the nice white cover drawn down tight to the side boards with a good ridge to keep from sagging. It is high enough for me to stand straight under the roof with a curtain to pull down in front and one at the back end. Now its all done and I get in out of the tumult... [Keturah Belknap, quoted in Daniel J. Hutchinson, Bureau of Land Management, and Larry R. Jones, Idaho State Historical Society, eds., Emigrant Trails of Southern Idaho, (Boise, Idaho: Idaho State Historical Society), 1994, p. 3.] |

Junction of Trails

Fort Hall, established in 1833 by Nathanial Wyeth of the Columbia River Fishing and Trading Company and operated by the Hudson's Bay Company since 1837, was a critical point of decision for the early travelers along the overland trail. The fort was located on the south bank of the Snake River, three and one-half months travel and 1200 miles from Missouri and almost three months and 600 miles from the Sacramento Valley. The fort was the third and last trading station on the overland trail and here travelers made final preparations for the most difficult stage of their journey and final decisions on their ultimate destination.

Beginning in 1843, former mountain man Caleb Greenwood, hired by California trader, cattleman, and pioneer John Sutter to lure and guide the Oregon bound to California (and willingly granted a pulpit at the British-operated fort), proselytized to the exhausted and confused on California's greater virtues and easier access. [48] Bud Guthrie immortalized Greenwood in the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Way West:

[From Fort Hall to Boise] there's the Snake to ford twice. . . . The Snake ain't no piss-piddle of a river even if you might think so, seein' it from here, but you'll get over, most o' you, and maybe some wagons. . . . Damn me fer a liar if fer days you don't roll along her rim and no drink for man or brute, and there she flows, so goddam far and steep below. . .

Californy way is too by-jusus tame. Nothin' the whole length of her to test a man. Nothin' to remember 'cept easy goin'. . . . [They raise] nothin' cept what's sot in the ground and whatever chews on grass. She's a soft country, she is, and so goddam sunny a ma wonders ain't there ever no weather there. It ain't like Oregon thataway. [49]

After the 1849 discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill, Greenwood's services were no longer required. Gold proved a powerful incentive against which the promised virtues of Oregon paled.

Two days past Fort Hall, the trail split, right to Oregon, left to California. Jacob Hayden, traveling in 1852, described the decision thusly:

We arose this morning with a full determination of going to Oregon, but when we reached the junction of the road, the team stopped. Part of us, after everything was taken into consideration, concluded to try our fortunes in California; the remainder gave in and we concluded to let the oxen decide our destiny. We started them and awaited the issue with great anxiety; they turned to the left, leaving the Oregon road to the right. [50]

|

Saw some men this evening that came by the way of Salt Lake. They report that ther [sic] will be a great many emigrants detained thee [sic] till after harvest, being no provisions [sic] to be had... They also say that it is 100 miles farther to come the Lake route. [Thomas Cristy, 7/1/1850, quoted in

Wells, "History of the City of Rocks" (1990), Appendix II, p.

6]

|

Those firm in their commitment to Oregon also faced a decision at the crossing of the Raft River: to proceed on the main trail along the Snake River or along alternate routes that took them south through the City of Rocks. The direct route was damned both with insufficient water for man and stock and too much water at the deadly fords. Oregon's Blue Mountains also presented a formidable front, as did the toll road around Mount Hood. For those who could not or chose not to pay the toll, the road ended at The Dalles on the Columbia, at which point emigrants proceeded downriver, in a dangerous conclusion to their journey. In 1846, the Applegate brothers scouted an alternative to this main Oregon road. Those choosing the Applegate Trail followed the California Trail through the City of Rocks, across Granite Pass, to a point near Winnemucca, Nevada, "thence northwest over Black Rock desert and the Cascade Range into the Rogue River Valley, and thence north to Salem, Oregon." [51] As with all of the alternatives, there were tradeoffs: travelers avoided crossing the Snake and the Columbia Dalles, yet faced "appalling difficulties" in Nevada's High Rock Canyon. [52]

After the 1862 Boise Basin gold strike, wagons traveling north from Salt Lake City forged a road from the Salt Lake Alternate to "Junction Valley," where they broke north off the California Trail, following the bench above Birch Creek past the present town of Oakley, and rejoining the Oregon Trail near Rock Creek. [53]

The Salt Lake Alternate, South Pass to City of Rocks

Mountain man and entrepreneur Jim Bridger established the Fort Bridger trading post south of South Pass in 1843. Those who traveled to the fort had the option of cutting north to Fort Hall on the main road — a circuitous and unappealing alternative that added miles to an already-too-long journey — or, by 1846, of following Lansford Hastings' trail across the Bonneville Flats to the main road along the Humboldt. This latter, untenable route fell into disuse following the experience of the Donner party. [54]

|

[At the crossing of the Raft River], the Oregon and California roads separate, and we are glad to learn that only about 60 or 70 wagons, out of 750, except the Mormons, are taking the road to California. The Mormons stop at the great Salt Lake... |

By 1848, one year after the Mormon exodus from Nauvoo to the Salt Lake Basin, California emigrants in need of rest and provisions had again diverted in large numbers south from South Pass to the Mormon "half-way house" of Salt Lake City (luxuries included a shave, new eyeglasses, a bed, a good meal). From Salt Lake City, they left behind "civilization, pretty girls, and pleasant memories," and proceeded north along the Salt Lake Alternate. This route was established in 1848 by Samuel Hensley, a member of the 1841 Bartleson Bidwell party, and first traveled by H. W. Bigler's Mormon battalion, returning to Salt Lake City following the Mexican-American War. The route crossed the Bear River approximately one week (80 miles) north of Salt Lake City, cut west northwest across the southeast corner of what is now Idaho, and met the main California Trail at the south "gate" to City of Rocks. The granite monolith christened "Twin Sisters" by a member of the battalion marks this southern entrance. [55]

Mormon emigrants, years behind the 1847 hegira, also followed this alternate, leaving the main California Trail at City of Rocks, and traveling east against the grain to the Salt Lake Basin — the land "that no one else wanted." [56]

|

[Along Hudspeth's Cutoff] the whole earth shows the effects of earthquakes. The rocks are thrown out of the earth in all confused forms imaginable, filling the earth with caverns and holes, rendering it dangerous to travel for either man or beast. The rolling of our wagons over the road produces a roar that sounded as though the earth was not two feet deep. [Pigman, 1858, quoted in Cramer,

"Hudspeth's Cutoff southeastern Idaho, a map and composite diary," p.

21.]

|

In 1849, Benoni M. Hudspeth and John J. Myers blazed a route along an "old Indian trail" running from the big bend of the Bear River (near Soda Springs) to Cassia Creek in the Raft River Valley, thus avoiding the long detour north to Fort Hall and then back along the Raft River toward the City of Rocks. When Hudspeth, Myers, and the large party of Missouri miners that had employed them as guides emerged from the rugged mountains along the east bank of the Raft River (near present-day Malta), they were reportedly "'thunder struck' to find they had not reached the Humboldt at all." [57]

|

[At the head of the Raft River] "such beards & faces! — all white with dust — our animals ditto. A wash was quite refreshing. Here we had dense willows to shelter us from the cold mountain blast." [Eleanor Allen, quoted in Hutchinson

and Jones, eds., Emigrants Trails of Southern Idaho, p.

97.]

|

Although the route was exceptionally rugged and passable only to west-bound wagons, it saved 22 miles and a day's travel over the road to Fort Hall. To footworn men and women in a hurry, this savings was considerable. By October of 1849, General P.F. Smith recommended against establishing a permanent United States military post at Fort Hall, noting that much of the emigrant traffic traveled Hudspeth's Cutoff instead (Figure 7). [58]

The City of Rocks

Between 1841 and 1860, the various overland roads funneled as many as 200,000 men, women, and children through the City of Rocks. [59] Historian John Unruh argues persuasively against "the language of typicality" in describing their journey:

it seems axiomatic to distinguish between abnormally wet and abnormally dry years. . . . The inexorable growth of supportive facilities.. further negates the usefulness of a 'typical year' approach. . . . Similarly revolutionizing the nature of the overland journey were the diverse traveler-oriented activities of the federal government: exploration, survey, road construction, postal services, the establishment of forts, the dispatching of punitive military expeditions, the allocation of protective escorts for emigrat caravans, the negotiation of Indian treaties designed to insure the safely of emigrant travel.... The California gold rush accelerated the amount of eastbound trail traffic.... Trail improvements contributed to significant reductions in the amount of time required to travel the overland route. [60]

|

One day west of the City of Rocks. Never saw such dust! In some places it was actually to the top of the forewheels! Fine white dust, more like flour. Our men were a perfect fright, being literally covered with it... |

Between 1841 and 1848, the journey from Missouri to California consumed an average of 157 days; add the years 1849-1860, and the average drops by over a month, to 121 days. After the great Mormon migration of 1847, those whose provisions, wagons, stock, or resolve had failed had the option of detouring to Salt Lake City. Prior to 1849, emigrants were primarily families of farmers, hopeful of settling — of staying — in California and Oregon. After the 1849 discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill, the wagon trains were joined by single men, unencumbered with heavy loads and hopeful of leaving California once they had struck it rich in the placer deposits of the Sacramento Valley; by 1850, both those who were successful and those who failed added a stream of east-bound traffic to the migration. [61] By 1852, the gold fever had waned and "families seeking new homes" once again replaced the fortune hunters. For those traveling between 1851 and 1862, when the threat of death from hostile Indians kept pace with the threat from cholera or accident, the journey west of South Pass was significantly more dangerous than for those who had preceded and those who would follow. [62]

|

Approaching City of Rocks Early breakfast, & soon on the trail again, — which winds up this deep valley, from S. by E. round to N.W. - An entire range on our left, of volcanic hills, for about 15 miles: and on our right, similar formations for about 10 ms. when we entered a very extraordinary valley, called "City of Castles." [J. Goldsborough Bruff (August 29,

1849), quoted in Wells, "History of the City of Rocks" (1990), Appendix

II.]

The circle is about 5 miles across one way & 3 the other, with only a narrow passage into it from the East 20 yds wide & another from the West 10 yds. Wide; the road passed through it. [John E. Dalton, July 26, 1852,

quoted in Wells, untitled manuscript, p. 49.]

|

Yet there were the constants of daily life — irrespective of the year, men and beasts needed food, water, and protection. Seven thousand five hundred mules, 31,000 oxen, 23,999 horses, and 5,000 cows accompanied the 9,000 California-bound wagons counted in Fort Laramie in 1852 — the peak year of emigrant traffic. Cut the numbers in half, for more "typical" years, and they remain impressive. These animals needed water when they "nooned" and again at the end of the day. The drain on the semi-arid West's water and browse resources was significant, necessitating that camp sites be varied and numerous and that the trail be spread over a many-mile radius, except in those areas where passage was limited to a narrow defile. [63]

At the northeast entrance to the City of Rocks, the trail constricted over Echo Gap (also called Echo Pass), and led to the Circle Creek basin. It constricted again at Pinnacle "Pass" east of Twin Sisters, and again at the head of Emigrant Canyon south of Twin Sisters, where the Salt Lake Alternate joined the main trail. Camp sites were available near "Register Rock" and "Camp Rock" where a number of springs provided water, along Circle Creek, and at the Emigrant Canyon spring. However, grazing resources at these sites would have been quickly exhausted in the late summer months when most emigrants arrived, suggesting that the Raft River Valley (east of City of Rocks), Big Cove (2 miles east of the City of Rocks, near Almo), and Junction Valley (2 miles southwest of the City of Rocks) would have been most often used as camping sites, particularly in the years of heaviest traffic and least rain. [64]

These camps provided not only an afternoon's or a night's rest, but also served as final havens of water and grass as migrants approached the long trek along the Humboldt River and the "Forty Mile Desert" past the Humboldt Sink. This was "the dreaded part of California travel, made more tragic by the weakened condition of so many emigrants and the death of so much of their livestock." [65] To avoid similar fates, trains would sacrifice precious days in the Raft River and Goose Creek regions to allow their stock to rest and feed.

Perhaps taking advantage of the brief interruption, and certainly in response to the approaching Granite Pass descent and Humboldt Desert travail, emigrants lightened their loads, jettisoning all but the essentials of continued travel: "at a fine spring and good grass we took dinner. Here the old Fort Hall road and the Salt Lake City road come together. . . . Here we overtook a company who were abandoning their wagons, and like us, packing." [66] As late as the 1970s, scattered remains of the wagons and abandoned personal effects remained within the City of Rocks. That they were only scattered attests not only to the passage of time, but to the extent to which subsequent emigrants salvaged and reused what others had left behind, especially the axles and wagon tongues used to make wagon repairs. And, as the Mormons struggled to forge a city in the wilderness, their salvage parties ranged in a wide arc north and east of Salt Lake: "especially welcome" were the tons of iron from abandoned wagons they brought back into the valley. [67]

After the establishment of Salt Lake City, life along the trail was not limited to those in transit. In 1849, J. Goldsborough Bruff encountered "2 Mormon young men....trading for broken-down cattle... They of course were from Salt Lake Valley." By the 1850s, Mormon entrepreneurs had established seasonal blacksmith shops in the Raft River Valley. Others traveled north from Salt Lake at regular intervals, to sell cheese, butter, eggs, and other perishables to the emigrants. [68]

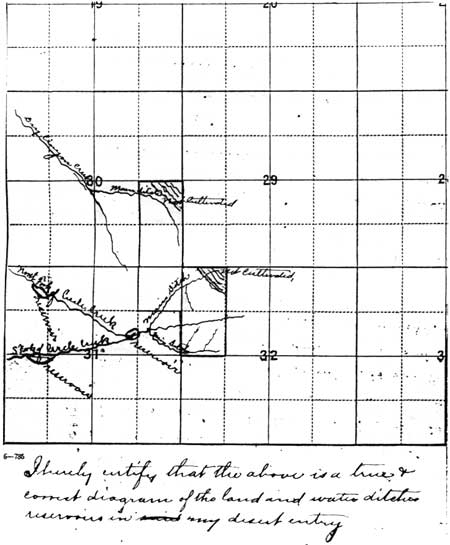

The Lander Road, Fort Keamy to Honey Lake

The first emigrants loudly protested their vulnerability to Indians and to the disingenuous misinformation of opportunistic trail guides. They lamented the rough and unimproved nature of the road and the lack of mail and supply posts, of hospitals, and of blacksmith shops. In 1857, Congress funded survey and construction of the Fort Kearny, South Pass, and Honey Lake Wagon Road, along which the City of Rocks served as one of three primary diversion points (see Figure 7). Between 1858 and 1860, federal crews, under the supervision of William M.F. Magraw (east of South Pass) and of Frederick Lander (west of South Pass) felled trees, constructed bridges, and developed reservoirs along a crude but graded highway known to emigrants as the "Lander Road." From Soda Springs to Fort Hall, this route ran north of the old emigrant road along a more direct route, through country reportedly blessed with ample water, grass, and timber. West of Fort Hall, minor improvements provided slightly better access to the City of Rocks. Beyond the city, road improvements ultimately included an improved western descent over Granite Pass and construction of reservoirs at Rabbit Hole and Antelope Springs northwest of the Humboldt River, lessening the danger of Humboldt Desert passage. [69] Completed in time for the 1859 travel season, Lander's Road served as many as 13,000 wagons in its inaugural year.

Construction of the Simpson Road from Salt Lake City due west to the Carson Valley (roughly paralleling the abandoned Hasting's Cutoff [see Figure 6] ) also impacted emigrant travel through the City of Rocks. The road, surveyed in 1859 by Captain James H. Simpson of the U.S. Army's Topographic Engineers, saved approximately 288 miles over the northern City of Rocks route — or approximately two weeks of emigrant travel. By 1860, the road had diverted winter postal and express carriers from the City of Rocks route (an inevitable change as Granite Pass had already proved impassable in winter) and served as the primary Pony Express route to California. In a promotional battle over the two roads — a battle reminiscent of the promises made by an earlier generation of trail guides and traders — high-ranking government officials preached the virtues of the Simpson route. By 1860 the traffic from Salt Lake had increased to the point that troops were deployed to protect the emigrant trains. Simpson himself admitted, however, to the "possibility" that those "desiring to travel through to California without passing through Great Salt Lake City . . . for purposes of replenishing supplies, . . . would be best to take the Lander cut-off at the South Pass and keep the old road along the Humboldt River." [70] Thousands of emigrants agreed, bypassing Fort Bridger and Salt Lake City and keeping to the Lander Road. Briefly, however, from 1860 until 1862, construction of the Simpson Road did halt most California-bound traffic on the Salt Lake Alternate to the City of Rocks. This traffic resumed in 1862, when gold was discovered in the Boise Basin. [71]

By 1860, emigrants faced a remarkably different journey than that undertaken by their predecessors: they traveled along surveyed and graded roads, crossed the most deadly rivers by bridge or ford, and watered their stock at constructed reservoirs. Blacksmith shops and trading posts had been established and mail could be sent and received enroute. [72]

"The Indian Menace"

There was reason to hurry. Although Indian danger along the overland trail has been greatly exaggerated (many more emigrants succumbed to drowning, disease, and accident; reminiscences of overland travel are much more likely to contain accounts of massacres than daily diaries), the Northern Shoshone and Bannock Indians between Fort Hall and the Humboldt were "considered among the most troublesome of the entire trail." Ninety percent of all armed conflict took place west of South Pass. [97]

The California and Oregon trails passed through the center of the tribal country of the Bannock (a branch of the Northern Paiute) and of the Northern Shoshone. Until approximately 1851, their interaction with emigrants was friendly, if cautious. In 1850, Hugh Skinner, reported that Shoshone Indians directed his party to water. Throughout the 1840s, emigrants hired the Western Shoshone to cut and carry grass and to watch and herd emigrant stock during overnight encampments. [98] In 1851, Caroline Richardson reported that "we are continually hearing of the depredations of the Indians but we have not seen one yet." [99]

As emigrant numbers increased through the early 1850s, the drain on the tribes' traditional grazing resources intensified, leaving Indian lands impoverished. Increased emigrant numbers also spelled increased white/American Indian contact: emigrants reported a dramatic increase in the number of stock stolen, while the Indians complained of unprovoked attacks, and federal Indian agents complained of the unethical behavior of white traders "who plied the natives with whiskey and sold them guns and ammunition." [100] Bannock and Shoshone hostility was further fanned by federal overtures to other tribes. In 1858 Indian Agent C. H. Miller argued that the government owed the Bannock just compensation for the destruction of their traditional winter range and the depletion of their hunting grounds. Without such payments, Miller and the "mountaineers" with whom he had consulted believed that the Indians would attack the first trains out of Fort Hall in 1859, in a desperate bid to prevent the destruction of those resources upon which they depended absolutely. Furthermore, "it has been in the most manly and direct manner that these Indians have said that if emigrants, as has usually been the case, shoot members of their tribes, they will kill them when they can." The federal government failed to negotiate successfully with either the Bannock or the Northern tribe, and the attacks continued. [101]

Most emigrants died individually, in isolated incidents, yet it was the massacres that captured public attention. In 1852, 22 emigrants were killed in the Tule Lake Massacre, and 13 in the Lost River Massacre; in 1854, 19 died in the Ward Massacre, 25 miles east of Fort Boise; in 1861, 18 members of the Otter-Van Orman train were killed 50 miles west of Salmon Falls on the Snake River. [102] The massacres were generally attributed to the Bannock and Shoshone, although eyewitnesses, Indian agents, army personnel, and the Oregon legislature reported the participation of "out-cast whites" who "led on . . . bands of marauding and plundering savages." [103]

Although the threat of death was of greatest concern, many more emigrants would experience the loss of their livestock: "it was the art of stealing horses which, at least according to emigrant testimony, the Indians had absolutely mastered." [104] Such theft was a significant blow, depriving emigrants of a food source, a transportation source, and the oxen, mules, and horses that pulled their wagons. In 1860, while traveling along the Raft River, emigrant James Evans wrote,

Indians hostile through all this region; came around camp every night, but could not be seen during the day. They stole 50 horses from one company. We kept two men constantly with the cattle whenever they were loose, and every man who had horses kept them constantly under his eye during the day . . . Kept two men watching around the encampment during the night with double barrelled shot guns, and revolvers. [105]

Others in the City of Rocks region were not so vigilant — or so lucky. On September 7, 1860 "Indians" who spoke English well attacked a four-wagon train in the City of Rocks vicinity, stealing 139 cattle and six horses. A month later, the Deseret News reported an attack on a wagon train encamped near the City of Rocks: "except for hunger, thirst and terror there were no casualties... The emigrants did, however, lose nearly all of their possessions." [106] In September of 1862, the Deseret News reported that Indians were pasturing over 400 head of stolen emigrant cattle on land just east of the City of Rocks. [107] By October of 1862, the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise had warned that "every train that has passed over that portion of the route in the City of Rocks since the 1st of August has had trouble with the Indians." [108]

In 1860, California-bound emigrants successfully petitioned for Army protection. Lieutenant Colonel M. T. Howe and 150 soldiers from Salt Lake City's Camp Floyd assumed responsibility for the main overland trail and the Lander Cutoff. Howe established a depot at the Portneuf River from which he escorted trains along the road between Fort Hall and the Humboldt Sink, through the City of Rocks. [109]

In 1862, Major Edward McGarry's US Army expedition killed 24 Indians in the City of Rocks vicinity, in retaliation for the Indian attacks. [110] Two years later, as the Indian assaults continued, Brigadier-General Connor ordered the Second California Volunteer Cavalry to "take steps to capture or kill the male adults of five lodges of Snake Indians who have for years infested the roads in that vicinity, and who have of late been stealing from and attacking emigrants to Idaho." [111] The battle of Bear River, "the severest and most bloody of any which has occurred with the Indians west of the Mississippi" ensued on January 29, 1863. [112] Although all the chiefs involved in the battle were Shoshone, historian Brigham Madsen reports that "the significance to the Bannock [lay] . . . in the effective and merciless manner in which the troops of the United States could and did check the resistance of a hostile tribe." [113] In July of 1863, United States Indian agents and military personnel negotiated treaties with Chief Washakie and the Eastern Shoshoni and with Chief Pocatello of the Northwest Shoshoni. In October of that same year, treaties were signed with the Western Shoshoni at Ruby Valley and the Gosiute Shoshone of Tuilla Valley.

By August of 1863, four Bannock chiefs informed James D. Doty of the Utah Indian Superintendency that their people "were in a destitute condition and . . . desired peace with the whites and aid from the government." Chief Tosokwauberaht (Le Grand Coquin) and two sub-chiefs, Taghee and Matigund signed the treaty of Soda Springs on October 14, 1863. The treaty established an estimated total Bannock population of one thousand, to whom the United States government would pay five thousand dollars [114] a year in annuity goods in compensation "for damages done to their pasture lands and hunting grounds." Article III of the treaty "exacted a promise from the Bannock that they would not molest travelers along the Oregon and California trails and along the new roads between Salt Lake City and the mines near Boise City and Beaver Head." [115]

|

Perspectives from Indian Country TO THE PUBLIC: From information received at this department, deemed sufficiently reliable to warrant me in so doing, I consider it my duty to warn all persons contemplating the crossing of the plains this fall, to Utah or the Pacific Coast, that there is good reason to apprehend hostilities on the part of the Bannock and Shoshone or Snake Indians, as well as the Indians upon the plains and along the Platte river. The Indians referred to have, during the past summer, committed several robberies and murders; they are numerous, powerful, and warlike, and should they generally assume a hostile attitude are capable of rendering the emigrant routes across the plains extremely perilous; hence this warning. [Indian Commissioner Charles E. Mix,

1862, quoted in Brigham Madsen, The Bannock of Idaho, p.

128.]

These Indians [Bannock and Shoshoni] twelve years ago were the avowed friends of the White Man I have had their Young Men in my Employment as Hunters Horse Guards Guides &c &c I have traversed the length & breadth of their Entire Country with large bands of Stock unmolested. Their present hostile attitude can in a great Measure be attributed to the treatment they have recd from unprincipled White Men passing through their Country... Outrages have been committed by White Men that the heart would Shudder to record. [Major John Owen (1861), quoted

Madsen, The Bannock of Idaho, p. 124.

|

Emigrants' Response to the City of Rocks

We are creatures shaped by our experiences; we like what we know, more often than we know what we like. . . . Sagebrush is an acquired taste, as are raw earth and alkali flats. The erosional forms of the dry country strike the attention without ringing the bells of appreciation. It is almost pathetic to read the journals of people who came west up the Platte Valley in the 1840s and 1850s and tried to find words for Chimney Rock and Scott's Bluff and found and clung for dear life to the cliches of castles and silent sentinels. [73]

While descriptions of a typical trail experience, transcending the vagaries of route and year of travel, are a dangerous historical exercise the same is not necessarily true of generalizations about migrants' psychological response to their journey. Historian John Mack Faragher, in his comprehensive study Women and Men on the Overland Trail, argues that emigrant diaries reveal a striking similarity in their pattern of organization and in their emphasis. "Things they had done that day" form the third most common notation; reports on families' health, comfort, and safety, the second.

|

The City of Rocks [It] is a city not built by hands, neither is it constructed out of wood or brick, but is made of a material more enduring than either... It is, in fact, a city of rocks... The space between the rocks is sufficiently wide to admit a horse and rider, so that one can ride in between and around them. They remind one of a grave yard, so solemn the place appears, and as one rambles among these rocks it seems to him almost as if the were trespassing upon sacred ground. [Charles Nelson Teeter (September

1865), quoted in Wells, untitled manuscript, p. 40.]

During the forenoon we passed through a stone village composed of huge, isolated rocks of various and singular shapes, some resembling cottages, others steeples and domes. It is called "City of Rocks," but I think the name "Pyramid City" more suitable. It is a sublime, strange, and wonderful scene — one of nature's most interesting works... Eight miles from Pyramid City we recrossed, going southwest, the forty-second parallel of latitude, which we had crossed going north, on the eighth day of June, near Fort Laramie. [Margaret A. Frink (July 17, 1850),

quoted in Wells, untitled manuscript, p. 45.]

Camped at Steeple or Castle Rocks here is a sublime scenery to the Romantic the rocks resemble an old City of Ruins there are thousands, of names here I registered Mine on a large Rock which we named the Cast[le] Rock hotel. [Richard August Keen, June 22, 1852,

quoted in Wells, untitled manuscript, p. 48.]

|

The most common notations, however, were of things they had seen that day: "the emigrants were startled and in some cases overawed by the imposing natural landscape and strange climate through which they passed. In terms of sheer preponderance, men and women emigrants mentioned the beauty of the setting more than any other single subject." [74]

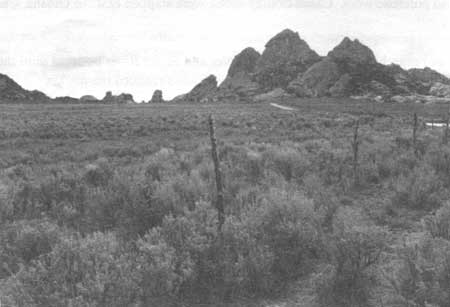

Those who traveled through the City of Rocks described the city in poetic and awe-struck detail. [75] And, as Wallace Stegner would later note, their descriptions of the "weird" configuration are striking in their consistent retreat to castles and silent sentinels. Rather than pathetic, this retreat may be a simple reality of language: they used the words they knew to describe what they had never seen. Yet their cliched adjectives do not disguise the wonderment with which they viewed the city or their extreme gratitude for the geographic diversion in a monotonous journey (Appendix A). [76]

Despite months on the trail, many had not yet adjusted to the size or immutability of the western landscape: upon approaching the vast Pyramid Circle, Helen Carpenter described a land base of "about an acre"; Lucena Parsons predicted "a few more years & then [the City rocks] will be leveled to the ground."

Carpenter wrote:

Emerging from [Echo Pass] we came into what is known as Pyramid Circle. There was perhaps a acre of partially level land with a good sized stream flowing through it. On this level, and the hills which encircled it, were the most beautiful and wonderful white rocks that we ever saw. This is known as the City rocks and certainly bears a striking resemblance to a city. To be sure it was a good deal out of the usual, for the large and small houses were curiously intermingled and set at all angles. There was everything one could imagine from a dog house to a church and courthouse. [77]

Vincent Geiger echoed:

You can imagine among these massive piles, church domes, spires, pyramids, &c., & in fact, with a little fancying you can see [anything] from the Capitol at Washington to a lovely thatched cottage. [78]

At City of Rocks, emigrants generally described what they saw, rather than what they did. Yet the logistics of the City of Rocks camping experience are easily recreated. As it had for the previous 100 days, camp had to be made and broken; the stock cared for (although the relative abundance of grass would have spared men the task of driving the herds miles from the trail); men, women, and children fed; in Indian country, in bad years, a careful watch mounted. Carpenter describes the ritual of travel, nooning, and camping:

the plain fact of it is we have no time for sociability. From the time we get up in the morning, until we are on the road, it is hurry scurry to get breakfast and put away the things that necessarily had to be pulled out last night—while under way there is no room in the wagon for a visitor, nooning is barely enough to eat a cold bite—and at night all the cooking utensils and provisions are to be gotten about the camp fire and cooking enough done to last until the next night.

Although there is not much to cook, the difficulty and inconvenience of doing it, amounts to a great deal—so that by the time one has squatted around the fire and cooked bread and bacon, and made several dozen trips to and from the wagon—washed the dishes . . . and gotten things ready for an early breakfast, some of the others already have their night caps on—at any rate it's time to go to bed.

In respect to women's work the days are all very much the same.... Some women have very little help about the camp, being obliged to get the wood and water (as far as possible), make camp fires, unpack at night and pack up in the mornings. [79]

Yet with all that, more than one woman would have echoed Carpenter's grateful "Am glad I am not an ox driver." [80] Men were charged with "the care of wagons and stock, driving and droving, leadership and protection of the family and party." On a normal day of travel:

the men of each family were up between four and five in the morning or cut their oxen from the herd and drive them to the wagon for yoking and hitching. The wagon and running gear had to be thoroughly checked over.... Normally a man drove each wagon . . . [and] some men herded and drove the stock to the rear of the line. A good morning march began by seven and continued until the noon hour, when drivers pulled up, unhitched their oxen, set the stock to grazing, and settled down for the midday meal the women produced.... Driving and droving were strenuous and demanding occupations.... Most [men] drove by walking alongside the trail. . . . Walking the fifteen or so miles of trail each day was, in the best of conditions, enough to tire any man Driving, and especially herding the cattle, meant eating large portions of dust: "It has been immensely disagreeable for the drivers today for a Northwest wind drove the dust in clouds into their faces . . . Am glad that I am not an ox driver." [81]

City of Rocks provided a welcome diversion from these travel rituals. Carpenter wrote:

While the stock was being cared for the women ad children wadered off to enjoy the sights of the city . We were . . . spellbound with the beauty and strangeness of it all. . . [82]

J. Goldsborough Bruff "dined hastily, on bread & water, and while others rested, . . . explored and sketched some of these queer rocks." [83] Young Harriet Sherrill Ward was similarly impressed. In a joyful description she painted a camp scene very different from the scenes that had preceded and those that would follow:

At eave we encamped in Pyramid Circle, a delightful place indeed. . . . Our tents and wagons grouped together and a merry party tripping the light fatastic toe upon the green, whose cheerful, happy voices echo from the hills around us, presents a scene altogether picturesque and novel." [84]

Emigrants consistently referred to the city as one of the memorable scenic wonders of a phenomenal journey: "This is one of the greatest curiosities on the road" wrote Eliza Ann McAuley in 1852. [85] Others agreed:

[Our] camp was pitched in a unique spot between Independence and Hangtown, one to be remembered along with Ash Hollow and Independence Rock for genuine singularity. . . . 'The manuscript of God remains Writ large in waves and woods and rocks.' [86]

Encamped in Granite City one of the finest natural places of its kind in the World, I banter the World to beat it. [87]

Within the Circle is one of the coldest springs seen on the route — and the Circle is surrounded on all sides with lofty mountains, covered with ever green Cedars; rendering the whole one of the most beautiful, grand. pictures[que] and delightful scenes I ever saw. [88]

|

I came to the junction of the roads [California Trail and Salt Lake Alternate], where there were many sticks set up, having slips of paper in them, with the names of passengers, and occasionally letters to emigrants still behind. [A. Delano, July 23, 1849, excerpt

provided by City of Rocks National Reserve.]

|

The City was unusual not only as a geographic oddity but also as a register of those who had gone before and as a rare and valued opportunity to communicate with those who followed. Count Leonetto Cipriani described "a cave used as a mail deposit... There were many letters, but none from the wagon company, a sure sign that it had not yet come by." The cave, at the base of what J.G. Bruff christened Sarcophagus Rock, is no longer visible, presumed buried by years of erosion and deposit. Yet elsewhere in the city vestiges of historic graffiti remain, marked with wheel grease or tar:

From the human standpoint, this Pyramid Circle is of greater interest because here we have another registration book of transcontinental travel. Rocks, walls, and monuments are covered with thousands of names and dates, and bear, as well, messages to on-coming friends and acquaintances. Some names date back to the earliest explorers. . . . The road from the Missouri River westward is lined with penciled messages or names and dates of passage. . . but Pyramid Circle is the volume de luxe. [89]

Although names and dates of travel are the dominant extant inscriptions, an occasional message remains legible, including O.E. Dockstater's terse "Wife Wanted." Emigrants also platted the city, signing rocks as "NAPOLEON'S CASTLE," and "CITY HOTEL"; those monoliths nearest the central trail were the most heavily inscribed. [90]

The larger countryside surrounding the City of Rocks, viewed in mid-August — at the end of the summer drought — was greeted with substantially less enthusiasm than the city itself. The vast majority of emigrants were "driven by a farmer's motives," and judged the passing countryside through the filter of what they had left behind in the well-watered east and what they expected to find in verdant California. They noted favorably the adequate grass along the Snake and Raft rivers but disdained the lands lying beyond the immediate water courses. [91]

In 1847, Chester Ingersoll reported:

. . . Since leaving the South Pass, it has been one entire volcanic region, all burnt to a cinder. The rock and stone look like cinders from a furnace. We have not had any rain for two months worth noticing. [92]

H.B. Scharmann cautioned:

The land . . . from Fort Laramie to California is not worth a [farmer's notice], I think. It consists of nothing but desert-land and bare mountains covered with boulders and red soil which makes them resemble volcanoes. The best thing the traveller can do is to hurry on as fast as possible from one river to the other. [93]

Leander Loomis added:

And we believe that some day there will be [gold] Discoverys made through here that will astonish the world. [I]f there is not something of this kind, in this country, it is folly in our opinions, for our Government, to try to settle it with White men, — for there is no timber through here, and if there was, there is (comparitive) no land fit for farming purposes from the Missouri to the Humboldt. [94]

Only the far-sighted recognized that grazing "would claim a high place on these lands." [95] The first generation of emigrants left their messages on the rocks and hurried to the next river, voicing no inclination to stay.

"When we had all gratified our curiosity, we bid the place adieu and rode away." [96]

"The Indian Menace"

There was reason to hurry. Although Indian danger along the overland trail has been greatly exaggerated (many more emigrants succumbed to drowning, disease, and accident; reminiscences of overland travel are much more likely to contain accounts of massacres than daily diaries), the Northern Shoshone and Bannock Indians between Fort Hall and the Humboldt were "considered among the most troublesome of the entire trail." Ninety percent of all armed conflict took place west of South Pass. [97]

The California and Oregon trails passed through the center of the tribal country of the Bannock (a branch of the Northern Paiute) and of the Northern Shoshone. Until approximately 1851, their interaction with emigrants was friendly, if cautious. In 1850, Hugh Skinner, reported that Shoshone Indians directed his party to water. Throughout the 1840s, emigrants hired the Western Shoshone to cut and carry grass and to watch and herd emigrant stock during overnight encampments. [98] In 1851, Caroline Richardson reported that "we are continually hearing of the depredations of the Indians but we have not seen one yet." [99]

As emigrant numbers increased through the early 1850s, the drain on the tribes' traditional grazing resources intensified, leaving Indian lands impoverished. Increased emigrant numbers also spelled increased white/American Indian contact: emigrants reported a dramatic increase in the number of stock stolen, while the Indians complained of unprovoked attacks, and federal Indian agents complained of the unethical behavior of white traders "who plied the natives with whiskey and sold them guns and ammunition." [100] Bannock and Shoshone hostility was further fanned by federal overtures to other tribes. In 1858 Indian Agent C. H. Miller argued that the government owed the Bannock just compensation for the destruction of their traditional winter range and the depletion of their hunting grounds. Without such payments, Miller and the "mountaineers" with whom he had consulted believed that the Indians would attack the first trains out of Fort Hall in 1859, in a desperate bid to prevent the destruction of those resources upon which they depended absolutely. Furthermore, "it has been in the most manly and direct manner that these Indians have said that if emigrants, as has usually been the case, shoot members of their tribes, they will kill them when they can." The federal government failed to negotiate successfully with either the Bannock or the Northern tribe, and the attacks continued. [101]

Most emigrants died individually, in isolated incidents, yet it was the massacres that captured public attention. In 1852, 22 emigrants were killed in the Tule Lake Massacre, and 13 in the Lost River Massacre; in 1854, 19 died in the Ward Massacre, 25 miles east of Fort Boise; in 1861, 18 members of the Otter-Van Orman train were killed 50 miles west of Salmon Falls on the Snake River. [102] The massacres were generally attributed to the Bannock and Shoshone, although eyewitnesses, Indian agents, army personnel, and the Oregon legislature reported the participation of "out-cast whites" who "led on . . . bands of marauding and plundering savages." [103]

Although the threat of death was of greatest concern, many more emigrants would experience the loss of their livestock: "it was the art of stealing horses which, at least according to emigrant testimony, the Indians had absolutely mastered." [104] Such theft was a significant blow, depriving emigrants of a food source, a transportation source, and the oxen, mules, and horses that pulled their wagons. In 1860, while traveling along the Raft River, emigrant James Evans wrote,

Indians hostile through all this region; came around camp every night, but could not be seen during the day. They stole 50 horses from one company. We kept two men constantly with the cattle whenever they were loose, and every man who had horses kept them constantly under his eye during the day . . . Kept two men watching around the encampment during the night with double barrelled shot guns, and revolvers. [105]

Others in the City of Rocks region were not so vigilant — or so lucky. On September 7, 1860 "Indians" who spoke English well attacked a four-wagon train in the City of Rocks vicinity, stealing 139 cattle and six horses. A month later, the Deseret News reported an attack on a wagon train encamped near the City of Rocks: "except for hunger, thirst and terror there were no casualties... The emigrants did, however, lose nearly all of their possessions." [106] In September of 1862, the Deseret News reported that Indians were pasturing over 400 head of stolen emigrant cattle on land just east of the City of Rocks. [107] By October of 1862, the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise had warned that "every train that has passed over that portion of the route in the City of Rocks since the 1st of August has had trouble with the Indians." [108]

In 1860, California-bound emigrants successfully petitioned for Army protection. Lieutenant Colonel M. T. Howe and 150 soldiers from Salt Lake City's Camp Floyd assumed responsibility for the main overland trail and the Lander Cutoff. Howe established a depot at the Portneuf River from which he escorted trains along the road between Fort Hall and the Humboldt Sink, through the City of Rocks. [109]

In 1862, Major Edward McGarry's US Army expedition killed 24 Indians in the City of Rocks vicinity, in retaliation for the Indian attacks. [110] Two years later, as the Indian assaults continued, Brigadier-General Connor ordered the Second California Volunteer Cavalry to "take steps to capture or kill the male adults of five lodges of Snake Indians who have for years infested the roads in that vicinity, and who have of late been stealing from and attacking emigrants to Idaho." [111] The battle of Bear River, "the severest and most bloody of any which has occurred with the Indians west of the Mississippi" ensued on January 29, 1863. [112] Although all the chiefs involved in the battle were Shoshone, historian Brigham Madsen reports that "the significance to the Bannock [lay] . . . in the effective and merciless manner in which the troops of the United States could and did check the resistance of a hostile tribe." [113] In July of 1863, United States Indian agents and military personnel negotiated treaties with Chief Washakie and the Eastern Shoshoni and with Chief Pocatello of the Northwest Shoshoni. In October of that same year, treaties were signed with the Western Shoshoni at Ruby Valley and the Gosiute Shoshone of Tuilla Valley.

By August of 1863, four Bannock chiefs informed James D. Doty of the Utah Indian Superintendency that their people "were in a destitute condition and . . . desired peace with the whites and aid from the government." Chief Tosokwauberaht (Le Grand Coquin) and two sub-chiefs, Taghee and Matigund signed the treaty of Soda Springs on October 14, 1863. The treaty established an estimated total Bannock population of one thousand, to whom the United States government would pay five thousand dollars [114] a year in annuity goods in compensation "for damages done to their pasture lands and hunting grounds." Article III of the treaty "exacted a promise from the Bannock that they would not molest travelers along the Oregon and California trails and along the new roads between Salt Lake City and the mines near Boise City and Beaver Head." [115]

|

Perspectives from Indian Country TO THE PUBLIC: From information received at this department, deemed sufficiently reliable to warrant me in so doing, I consider it my duty to warn all persons contemplating the crossing of the plains this fall, to Utah or the Pacific Coast, that there is good reason to apprehend hostilities on the part of the Bannock and Shoshone or Snake Indians, as well as the Indians upon the plains and along the Platte river. The Indians referred to have, during the past summer, committed several robberies and murders; they are numerous, powerful, and warlike, and should they generally assume a hostile attitude are capable of rendering the emigrant routes across the plains extremely perilous; hence this warning. [Indian Commissioner Charles E. Mix,

1862, quoted in Brigham Madsen, The Bannock of Idaho, p.

128.]

These Indians [Bannock and Shoshoni] twelve years ago were the avowed friends of the White Man I have had their Young Men in my Employment as Hunters Horse Guards Guides &c &c I have traversed the length & breadth of their Entire Country with large bands of Stock unmolested. Their present hostile attitude can in a great Measure be attributed to the treatment they have recd from unprincipled White Men passing through their Country... Outrages have been committed by White Men that the heart would Shudder to record. [Major John Owen (1861), quoted

Madsen, The Bannock of Idaho, p. 124.

|

The Kelton Road — "The Stage Era"

The flow of emigrant traffic through the City of Rocks ebbed after 1852 and virtually ceased following the 1869 completion of the transcontinental Union Pacific Railroad. [116] The City of Rocks remained an important transportation center, however, serving as a relay point and rest stop on the mail and stage route connecting the railhead at Kelton, Utah with the boom mining communities of the Boise Basin.

Since the founding of Salt Lake City, the Salt Lake Alternate to the Overland Trail had served as a freight route connecting the interior basin with the Pacific coast. Beginning in September of 1850, George Chorpenning and Absalom Woodward's government-sponsored mail wagons ran from Fort Bridger to Sacramento, by way of the Salt Lake Alternate and Granite Pass. [117] The route was abandoned in September of 1853, in response to harsh winters and Indian attacks, yet resumed briefly in 1858, when the Mormon War disrupted the San Bernardino route. Concord coaches or four-horse mud wagons passed through the region once a week, from July to December, 1858, when the route was again abandoned in favor of a central Nevada route west of Provo. [118]

Beginning ca. 1860, a local version of the famous Pony Express also ran through the City of Rocks, along a route that extended from Boise to Brigham City, Utah, by way of Rock Creek, Oakley, Goose Creek, City of Rocks stage station, and the Raft River Headwaters, and Kelton Pass. [119]

The discovery of gold in the Boise Basin in 1862 created a new market for Salt Lake goods, which in turn, resulted in a modification in the abandoned Chorpenning & Woodward route. Circa 1864, Ben Holladay of the Holladay Overland Mail and Express Company initiated a run from the railroad at Kelton, Utah, to Boise Basin mining communities. Holladay's coaches traveled to the City of Rocks region by way of the Salt Lake Alternate (Figure 8). Here they turned north, rather than west, proceeding over Lyman Pass (a gentle breach of the Albion Mountains), to Rock Creek along the Snake River. John Hailey of Boise purchased the Boise to Kelton route from C. M. Lockwood in 1868. [120]

|

|

Figure 8. Concord Gulch (Idaho State Historical Society photograph