|

City of Rocks

Historic Resources Study |

|

HISTORICAL CULTURAL RESOURCES IN THE CITY OF ROCKS NATIONAL RESERVE

The historical cultural resources within City of Rocks National Reserve most clearly reflect two phases of Euroamerican expansion into the west: the westward migration of the mid-1800s, and the settlement (homestead) era (1888-1929). Other themes important to the exploration and subsequent development of the region (e.g., the fur trade and development of the mining frontier) did not directly impact this small area at the southern end of the Albion Mountains. Tourism and recreation represent the most recent trends that have contributed to development within the area.

Although many different manmade resources are found within the reserve, their number is small relative to the number of improvements that once existed there. The area that they occupy is minor, compared with the expanse of open land that has never had, or does not obviously appear to have had, any improvement. The upper reaches of the reserve, those areas that consist mostly of rock, and slope, and timber, retain a wild appearance. The lower elevation basins have been more substantially altered. Currently, these areas are relatively free of structural components excepting various small scale elements such as fences and corrals. The once-numerous residential/outbuilding clusters of the dry-land farms no longer break the visual continuity of the two basin floors; remains of their presence consist only of artifact scatters, sometimes in association with stone foundations. Perhaps the most dramatic change within the lower basins is in the character of the vegetation. These basins no longer contain the mosaic of sage and native grasses that the westward emigrants would have encountered. The grubbed, plowed, and seeded fields of the dry-land farmers of the 1910s and 1920s have, in most cases, reverted to sagebrush mixed with non-native weedy grasses and forbs. In some areas, former cropland contains the ubiquitous sage interspersed with crested wheatgrass — the latter introduced to increase the quality of the range for cattle. [298] Questions of vegetative species composition aside, the current landscape character of the reserve is much the same as it would have appeared to emigrants passing through during the late summer months, after livestock from previous emigrant trains had grazed the lower elevations of the basins.

The following discussion is broken into three parts. The first presents information regarding cultural resources associated with westward migration. The second contains a description of the cultural resources associated with the settlement period. The final section includes a discussion of the configuration of historically significant resources within the reserve, and suggestions regarding the manner in which they may be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. Figures for Section 5 are presented at the end of the discussions.

Overland Migration

Resources historically associated with westward migration include:

Trail ruts and topographical indicators of trail routes

Inscription rocks

Geological landmarks with cultural value and historically important viewsheds

Encampment sites.

The first type of resource, includes both small-scale elements such as discontiguous segments of trail ruts, as well as areas where natural features (either grade or topography) define the trail route. Trail ruts are sets of parallel tracks left by the wagon wheels. In some areas, only a single pair of tracks is visible (Figure 19), in others (most notably in Section 23 T16S/R23E), several pairs of tracks occur roughly parallel to each other. Single sets of tracks tend to occur in topographically restricted areas, multiple alignments tend to occur in more level areas where drivers were able to spread out and travel abreast of one another. Multiple tracks may also be an indication of the need to avoid certain obstacles (e.g., a mud hole after a summer thundershower, or an eroded boulder).

|

| Figure 19. Single set of trail ruts on north side of Pinnacle Pass - view to north. |

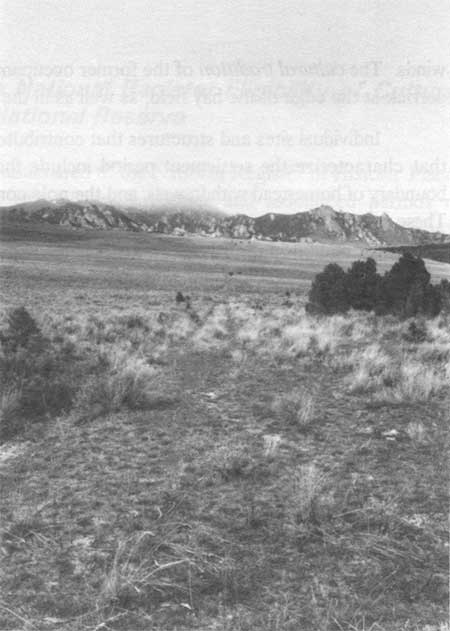

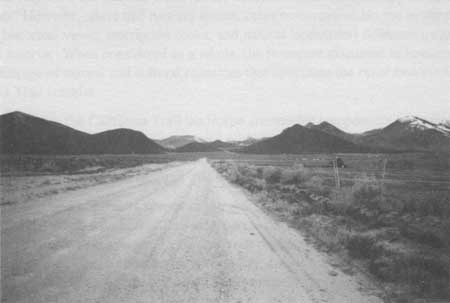

The second indicators of trail alignments are topographic restrictions — usually ridge saddles or canyons. The entry into the Circle Creek basin at the northeast edge of the reserve is a good example of a canyon restriction. Here, the close alignment of three steep topographic features restricts travel from the upper Raft River valley into the Circle Creek basin to two narrow passages on either side of a small steep-sided knoll (Figures 20 and 21).

|

| Figure 20. Looking west to City of Rocks entrance near Circle Creek. California Trail passed on either side of the small conical knoll in center of photo. View is from county road west of the City of Rocks National Reserve. |

|

| Figure 21. Looking east from inside the Circle Creek basin to the small conical knoll and the two routes of the California Trail. Raft River valley visible in rear-ground of photo. |

Within the reserve, Pinnacle Pass (10CA590) is probably the most prominent topographic restriction — located in the middle of a long continuous ridge of eroded granite, and marked on the west side by the Twin Sisters. Traveling east to west, emigrants would have faced a gradual ascent on the north side, followed by a steeper descent on the south. A distinct set of ruts is found on both the north and south sides of this pass (Figure 22) through an area containing moderately deep soil and vegetated primarily with sagebrush, except at the summit, where bedrock lies very close to the surface. [299]

|

| Figure 22. Trail ruts on south side of Pinnacle Pass - view to north. |

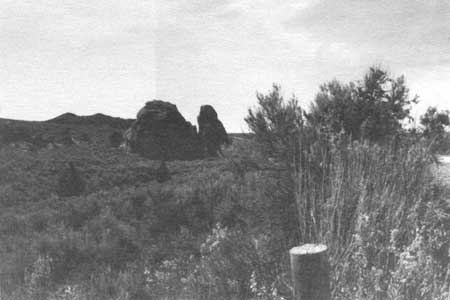

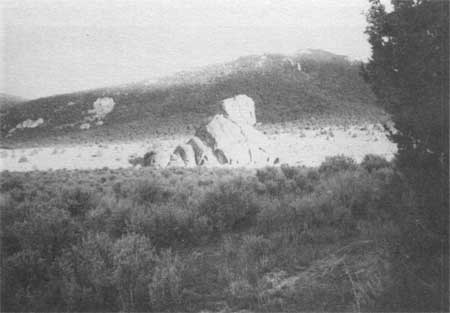

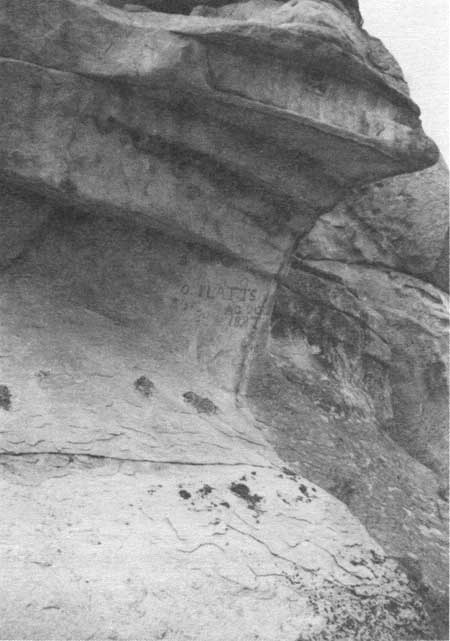

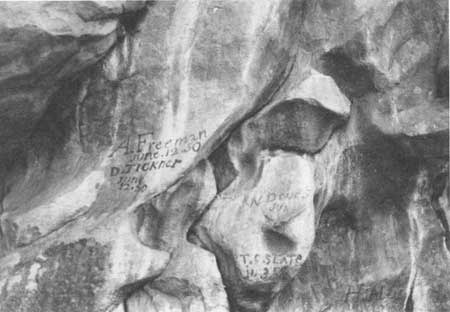

The inscription rocks are primarily located in the vicinity of the Circle Creek basin. A total of eleven monolithic granite outcroppings have been previously identified that contain inscriptions (10CA564, 575, 585, 586, 587, 588, 589, 591, 595, 596 and 597). These include the principal rock formations such as Camp Rock (Figure 23) and Register Rock (Figure 24), as well as less prominent formations (Figures 25 and 26). Inscriptions are barely visible on some rocks, having been badly eroded by wind (Figure 27). The most common inscriptions include the name of the transcriber and the date of the inscription, and are painted on the rocks with axle grease (Figure 28). A few inscriptions are incised — a more time-consuming process.

|

| Figure 23. Camp Rock (10CA504) to right with "Elephant head" and "Pagoda" (10CA585) to left - view to east. |

|

| Figure 24. Register Rock (10CA574). View is to south from County Road - formerly the California Trail. |

|

| Figure 25. Site 10CA591 - the "Monkey Head" - view to east. |

|

| Figure 26. Detail of inscriptions at the "Monkey's Head" - 10CA591. |

|

| Figure 27. Detail of eroded inscription at 10CA596, "Kaiser's Helmet." |

|

| Figure 28. Detail of inscriptions on Register Rock. |

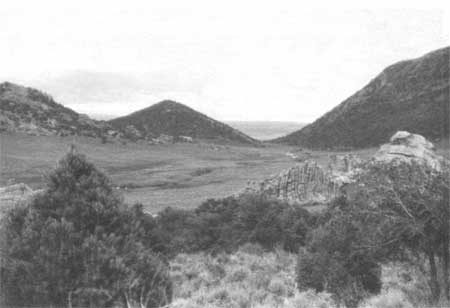

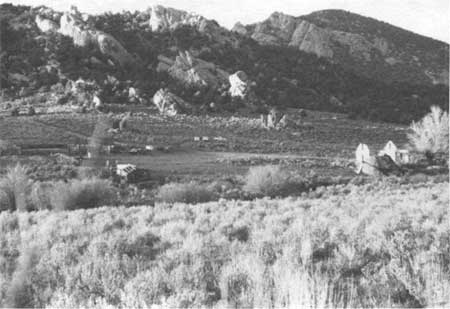

Within the reserve the most obvious example of natural features with cultural significance is the "rock city" that rims the Circle Creek basin. The basin is reported to have been a preferred campsite for emigrants, graced with a reliable source of water and a natural meadow. Emigrants on the main California Trail would have seen the outcroppings above the Little Cove while they were still in the main Raft River valley. However, it is within the Circle Creek basin that the effect of the outcroppings is most strongly felt. Although it is actually quite large (one and one-quarter miles east/west by three-quarters of a mile north/south), the huge scale of the rocks makes the basin appear smaller and more sheltered than it actually is (Figures 29 and 30). It is not until one walks from one side of the basin to the other and stands at the base of a large outcrop that one realizes their great size. The viewshed of the Circle Creek basin, incorporating all lands from the stream channel to the top of the peaks that encircle the basin, represents a historically important view and setting for the Circle Creek encampment and the California Trail. [300]

|

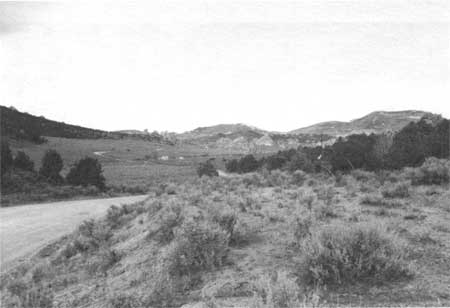

| Figure 29. Looking southwest into Circle Creek basin from main City of Rocks access road. |

|

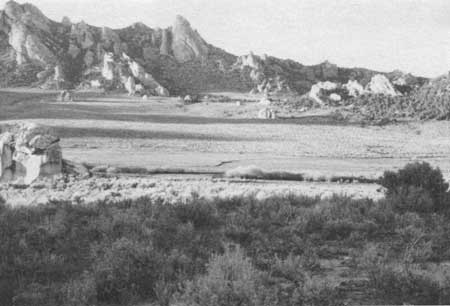

| Figure 30. Looking north across Circle Creek basin to granite formations that rim the basin. |

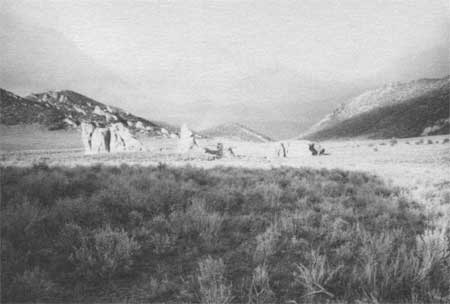

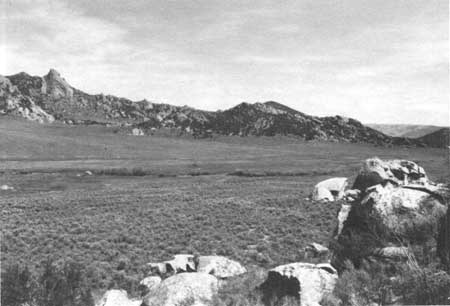

Another area that likely was used as an encampment is the basin northeast of the ridge that contains the Twin Sisters and Pinnacle Pass. Although this area does not appear to contain as reliable a water supply as the Circle Creek basin, several springs are located in the vicinity. The broad expanse of the basin bottom would have provided forage for livestock, and the area in general was a place to rest before the last uphill pull to Pinnacle Pass. As stated previously, this basin is marked by the Twin Sisters — a prominent landmark — and by the rocky ridge and series of bedrock outcrops that rim the west side of the basin. Like the Circle Creek basin, this area represents a historically important setting for the California Trail.

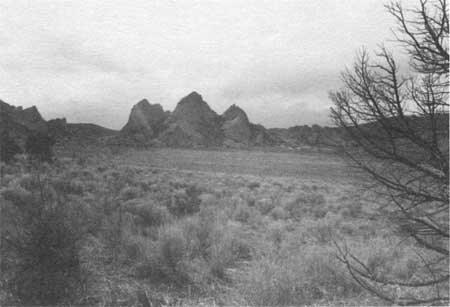

A separate discussion of the cultural importance of the Twin Sisters is warranted. Both travelers on the main California Trail (Figure 31) and those using the Salt Lake Alternate commented on this formation. For those using the Salt Lake Alternate, the Twin Sisters was the only component of the City of Rocks observable from the trail (see Figure 3). It marked the junction of the two trails, and for a few, the final point for choosing between California and Oregon as their final destination.

|

| Figure 31. The Twin Sisters viewed from the Twin Sisters basin - view to west. |

The drainage that contains the junction of the two trails also represents a historically important setting. Here, the Cedar Hills block further southerly progress; east/west progress is facilitated by a breaks in the topography of the hills. The Salt Lake Alternate enters the reserve from the east, through Emigrant Canyon. Westward travel along the combined routes proceeds up a gentle incline, and then down into the valley of Junction Creek.

The historically significant viewsheds described above are integral to the City of Rocks cultural landscape; their integrity is critical to the integrity of the cultural landscape as a whole. Consideration should be given to enlarging the reserve boundary to include the components of historically significant viewsheds that are located outside the present reserve boundary.

Resources Related to Settlement

Cultural resources associated with the settlement period include:

Boundary demarcations (small-scale elements such as fences and corrals)

Remains of residential clusters and irrigation improvements

Historic and modern-era mines.

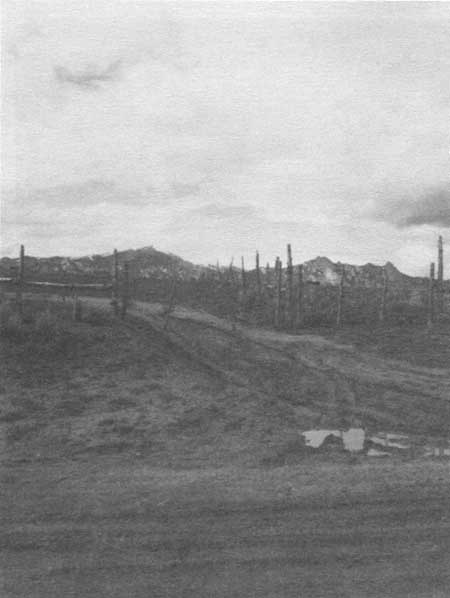

As stated previously, the number of extant resources remaining from the settlement period is small compared to the number of improvements that once were present within the reserve. The most common structures of the settlement period are the fences (and gates) that mark the boundaries of homestead withdrawals. Fence lines usually are built along section lines, and reflect the pattern of withdrawing land according to government land surveys. Although the fabric has been replaced, most fences erected on private lands are still made of juniper posts and barbed-wire (Figure 32). [301] Although the area is no longer used for dry-land farming, the fences continue to mark section lines and currently separate livestock pastures.

|

| Figure 32. Overview of juniper post and barbed-wire fence. |

Other small-scale elements include a limited number of isolated corrals (built with poles and dimensional lumber). These are found in isolated areas (away from residential building clusters) and reflect the use of the area for livestock grazing and management (Figure 33).

|

| Figure 33. Pole stock corral located within Eugean Durfee homestead withdrawl - view to northeast. |

The remains of the residential clusters associated with homestead withdrawals occur in a variety of configurations. Some have been reduced to simple artifact scatters and depressions. These include the Mikesell homesite (10CA594), the Charles Fairchild homesite (10CA593), the Thomas Fairchild homesite (Figure 34), and the Walter Mooso homesite. Others, such as the Moon homesite (10CA551) [302] and the John Hanson homesite, contain a richer array of resources, which includes artifact scatters, aboveground ruins of buildings or structures, and foundation remains (Figures 35 and 36). Although these sites would not be considered individually eligible, they function as contributing components of the landscape within which they function as placemarkers of past homestead activity.

|

| Figure 34. Looking north to large limber pine that marks the location of the Thomas Fairchild homesite. Artifacts are distributed across the rocky outcrop at the base of the tree. |

|

| Figure 35. Building ruin at the Moon homesite. |

|

| Figure 36. Foundation remains at the John Hanson homesite. |

Only one historical homestead property, the Circle Creek Ranch, retains the residential cluster (Figure 37), irrigation improvements and an intact hay meadow. This property is located in the Circle Creek basin, where George Lunsford withdrew 160 acres under the 1862 Homestead Act, receiving a patent to his land in 1888. Lunsford sold his land to William Tracy in 1901. This parcel, plus 160 adjacent acres patented by Mary Ann Tracy as a Desert Land entry, formed the nucleus of the Circle Creek Ranch. The Tracys established their homesite farther east than Lunsford's original improvements, nearer the California Trail. They spent years constructing a substantial stone house (now in ruins) to replace their log dwelling (possibly one of Lunsford's original buildings). The stone used in the construction of the home is from a quarry located about one mile southwest of the homesite, on a rocky knob that is locally known as "Mica Knoll." [303]

|

| Figure 37. Looking north northeast to residential building cluster, ruins of Tracy's Circle Creek Ranch. |

William Tracy built a series of dams on Circle Creek and irrigated a small hay meadow with a ditch extending from the ponds (Figure 38). The current property owner (Nickleson) continues to use this meadow for agricultural purposes. Although he no longer harvests hay, the meadow is leased to a local rancher, who turns cattle into the meadow to graze during the summer and fall. This use requires that the meadow be "dragged" in the spring, in order to break up and disperse the cow manure. This continuity of use has kept the meadow free from sagebrush. A Mormon hay derrick is located at the north margin of the meadow — testimony to previous, more intensive use of the hay field.

|

| Figure 38. Overview of irrigated hay meadow on Circle Creek Ranch, the residential building cluster is located at the extreme right of photo - view to northeast. |

Only two mines have been developed within the reserve, neither of which was formally withdrawn for mineral development. The mines are included under the general settlement theme, because they both appear to represent "moonlighting" activities of people whose primary livelihood was derived from agricultural pursuits.

The first mine is the feldspar/stone quarry located on Mica Knoll and discussed above in the context of the Tracy's Circle Creek Ranch. Local informants refer to the "Lloyd mica mine" also being located on the knoll. Indeed there is evidence of at least nine separate excavations that extend over the top and sides of the knoll (Figures 39 and 40). These excavations are small and it does not appear that the volume of material (mica and/or feldspar) removed from the area was very large.

|

| Figure 39. Detail of excavations on Mica Knoll. |

|

| Figure 40. Detail of roofed excavation on Mica Knoll - view to north. |

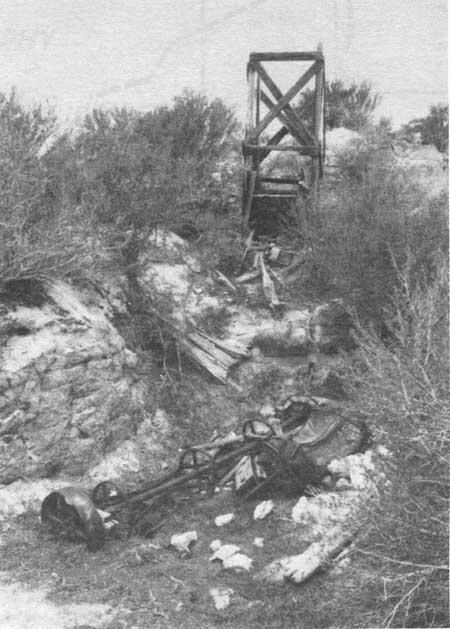

The second mine is referred to by local residents as the "Vern White mica mine," and appears to represents a late 1940s/1950s endeavor (Figure 41). Local informants indicate that the mica from this mine was used for insulation. [304] Local tradition regarding this mine explains that it was developed as part of a stock scam (i.e., shares were sold to investors when there was really no indication that the mine would be profitable), and that it was short-lived. The first tradition has not been confirmed; it is possible that the owner of the mine believed that he could produce a marketable quantity of mineral from the deposit, and that he did not intentionally mislead investors. [305]

|

| Figure 41. Tipple and Ore Bin at Vern White Mesa mine. Main excavation is behind (southwest) this structure. |

Recommendations Regarding the National Register Eligibility of Cultural Resources within City of Rocks National Reserve

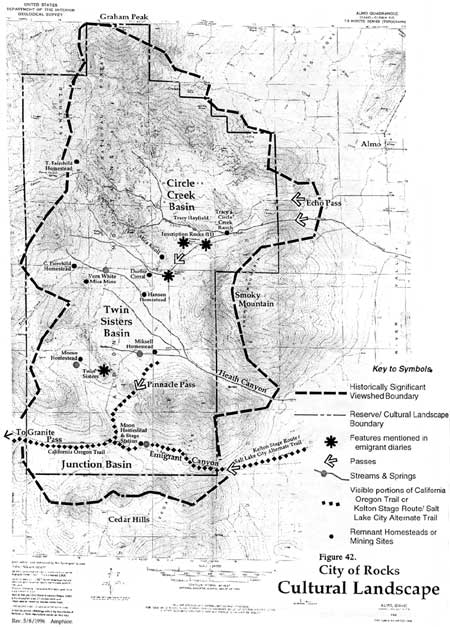

HRA recommends that the reserve be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as a rural historic landscape, representing two historical themes and associated periods of significance. The district would qualify for listing under National Register criterion A, under the area of significance entitled Exploration and Settlement. Figure 42 shows the principal cultural and natural resources that contribute to its significance, including significant historic viewsheds that should be considered for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, but are outside the reserve boundary. The historic district boundary is the same as the reserve boundary.

|

| Figure 42. City of Rocks Cultural Landscape. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Extant historical cultural resources located within the reserve are associated with westward emigration and with the settlement era. With regard to the theme of emigration, a discussion of the character of migration trails is in order. The selection of a trail route is, in essence, a human response to the natural environment. The individuals who pioneered and promoted various routes did so on the basis of the needs of the emigrants who would follow. They took advantage of the natural land contours to seek the path of least resistance (for wagons and livestock) and, when necessary, diverted to access natural resources (water and livestock forage), and human services (supply centers, blacksmith shops, etc.). Emigrants attributed special importance, (cultural value), to various natural features observed along the trail — usually features that broke the monotony of slow travel through a landscape that changed little from day to day.

Within City of Rocks National Reserve, the California Trail does not appear as a continuous set of trail ruts. However, where trail ruts are absent, other resources within the larger trail corridor (significant historical views, inscription rocks, and natural landmarks) delineate its general route through the reserve. When considered as a whole, the resources discussed in Section 5.1, form a continuous linkage of natural and cultural resources that constitute the rural historic landscape of the California Trail corridor.

Nested within the California Trail landscape are smaller components representative of the settlement period. Of the properties associated with this theme, the Tracy's Circle Creek Ranch comprises a small historic district. This district consists of the ruins of the residential building cluster, the circulation system of dams and irrigation ditches, and the hay fields.

The Tracy property exhibits several of the characteristics found in rural historic landscapes. The selection of the original withdrawal, to incorporate the water source and natural meadow, and the placement of the hayfield adjacent to Circle Creek represent patterns of land use typical of the early homestead period. The southern property boundary, constructed with juniper poles and barbed wire, reflects the division of property according to government surveys, and thus the overall spatial organization of the homestead era. The response to the natural environment is evident in the selection of construction materials for the buildings in the residential cluster and the boundary fences, and in the placement of the complex near the edge of the basin in an area protected from prevailing winds. The cultural tradition of the former occupants is apparent in the presence of a Mormon hay derrick at the edge of the hay field, as well as in the use of stone in the dwelling. [306]

Individual sites and structures that contribute to our understanding of the cultural traditions that characterize the settlement period include the quarry on Mica Knoll, fences that mark the boundary of homestead withdrawals, and the pole corral on the Eugene Durfee homestead property. These cultural resources reflect human responses to the natural environment and patterns of land use of the second period of historical significance.

Although modern, non-contributing improvements occur within the proposed district (e.g., the modern county road), they do not detract significantly from the overall character of the area, which retains its historical appearance. Overall, the district retains sufficient integrity for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

ciro/hrs/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 12-Jul-2004