|

FORT PULASKI AND THE DEFENSE OF SAVANNAH

Originating on the slopes of the Appalachian Mountains, the Savannah

River flows east, forming the boundary between South Carolina and

Georgia. Twelve miles from the coast it passes Savannah, joined by

hundreds of interconnecting channels twisting their way into the sea.

Among the channels are hundreds of tidal islands. They are covered with

grass and reeds and resemble a savannah at low tide. Closest to the

ocean is a deposit of mud lying between the two channels of the Savannah

River; it is Cockspur Island and the home of Fort Pulaski.

Fort Pulaski was part of the defense of Savannah, the most strategic

point along the Georgia coast. The expanding international cotton

industry made Savannah a major international port in the pre-Civil

War South. Three railroads converged on the city. Shipbuilding, marine

industries, and railroad shops were the primary military industries.

Forts such as Pulaski had two missions—to prevent the passage of

ships and to resist attack. Stopping ships required the proper number

and caliber of guns. Ground defense required inaccessibility and

distance from bombarding artillery. Fort Pulaski was ready for both

missions. Before the Civil War, the chief engineer of the United States

Army had said, "You might as well bombard the Rocky Mountains as Fort

Pulaski. . . . The fort could not be reduced in a month's firing with

any number of guns of manageable caliber."

Cockspur Island had been the site of forts since

pre-Revolutionary War days. First was Fort George in 1761, a

palisaded log blockhouse dismantled and abandoned by patriot forces in

1776 because it was indefensible against the British fleet. Fort Greene,

named for the Revolutionary War patriot Nathanael Greene, who is buried

on nearby Mulberry Grove Plantation, was built in 1794-95. In 1804 a

hurricane swept Cockspur, destroying the fort and drowning part of the

garrison. The island remained unused until the 1820s.

|

A SKETCH OF FORT PULASKI FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY BY "AN OFFICER OF

THE NAVY."

|

Fort Pulaski was part of a coastal defensive system begun after the

War of 1812 that stretched from Maine to Louisiana. Although Cockspur

was chosen as a site in the early 1820s, construction did not begin

until 1829. The original plans called for a structure identical to Fort

Sumter—a two-story pentagonal fort with three tiers of guns.

Engineers determined that Cockspur's muddy composition would not support

such a weight of masonry. The plan was modified to a single story, one

row of casemate guns, and above, a row of parapet (barbette) guns.

Construction was initially supervised by Major Samuel Babcock. In the

autumn of 1829 Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, newly graduated from the United

States Military Academy, arrived as Babcock's assistant. Ill health

prevented Babcock from taking an active role and it fell to Lee to

locate the site of the fort and to begin the construction of the

drainage canals and dikes. Assigned to Virginia in 1831, Lee would not

visit the fort again until the Civil War. In 1833 the partially

completed fort was named for Count Casimir Pulaski, who had been

mortally wounded in 1779 in the battle of Savannah. Malaria, yellow

fever, typhoid, and dysentery halted work each summer. Work continued,

largely under the direction of Lieutenant Joseph K. F. Mansfield, and

the fort was completed in 1847.

|

AN ILLUSTRATION OF SAVANNAH, GEORGIA, CIRCA 18634. (FMTW)

|

Twenty-five million bricks were used to build the fort; most were

made on nearby plantations. Granite and sandstone were brought from New

York and Connecticut. The Corps of Engineers rented slaves from

neighboring plantations for hard labor; masons and carpenters came from

Savannah and the North. Twenty 32-pounder naval guns were installed in

1840. Although the fort was designed for 150 guns, not a single gun was

added until after it was seized by Georgia authorities in 1861.

Fort Pulaski has five sides, called faces. Two guard the south

channel of the Savannah River; two, the north channel. The gorge, the

least vulnerable side of the fort, faces west toward Savannah. The three

ocean-facing angles of the fort each had a short face, the pan

coup&ecute;, at the angle of the walls. Each pan coup&ecute; has a single

casemate and embrasure (opening) for a gun to protect the potential

blind spot at the angle. All the walls of the fort are seven and a half

feet thick and rise twenty-five feet above the water-filled moat. The

gorge is protected by the triangular demilune, which has been remodeled

and differs today from the original design. The entire structure is

surrounded by a moat, 48 feet wide around the fort and 32 feet wide

along the demilune.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

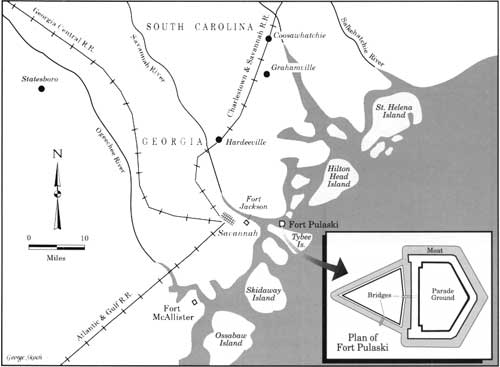

Principal transportation routes and defenses of Savannah.

Fort Pulaski protected this important commercial center from seaborne attack.

The fall of Pulaski greatly strengthened the Federal blockade of

Southern ports. Fort Pulaski protected this important commercial center

from seaborne attack. The fall of Pulaski greatly strengthened the

Federal blockade of Southern ports.

|

South Carolina passed her Ordinance of Secession on December 20,

1860; the news was greeted in Savannah with celebration and

demonstrations of support.

|

South Carolina passed her Ordinance of Secession on December 20,

1860; the news was greeted in Savannah with celebration and

demonstrations of support. Six nights later, the militia and

torch-bearing citizens marched through the city. That same night Major

Robert Anderson's Federal troops slipped from Fort Moultrie on Sullivan

Island into Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Outraged Georgians

protested in Savannah; the mob called for the siezure of Fort Pulaski

before it, too, could be used to block the river and access to the port

of Savannah. On January 1, 1861, Governor Joseph E. Brown met with

Colonel Alexander R. Lawton, commander of the 1st Volunteer Regiment of

Georgia, along with various regimental officers, to plan the seizure of

Fort Pulaski. Meetings continued the next day. Early on January 3,

details of infantrymen and artillerymen, accompanied by six small

artillery pieces, marched to the waterfront in the rain, amid cheering

crowds. There, they boarded the commandeered United States sidewheel

steamer Ida and descended to Cockspur. Landing at the north

wharf, the Georgians marched into the fort, then under the care of an

ordnance sergeant who surrendered the fort, its rusting guns, and a

small supply of powder and ammunition. Taking possession of the fort,

Colonel Lawton raised the Georgia flag over the ramparts. On January 16,

1861, the Georgia state convention met to consider the state's course;

they voted to withdraw from the Union and passed Articles of

Secession.

Fort Pulaski had been neglected badly over the years. The quarters

were unfit to live in; the overgrown parade was unusable; a morass of

silt and marsh grass filled the moat. Even with the labor of 125 slaves,

the Georgians spent months restoring the fort to livable and defensible

condition. The men strung a telegraph wire between the fort and

Savannah.

During the first half of the year, the 1st Regiment of Georgia

Volunteers, along with other state troops, prepared Fort Pulaski and a

network of defenses on neighboring islands and waterways. These defenses

stretched from earthen Fort McAllister on the Great Ogeechee River into

South Carolina to the north.

|

THEODORE DAVIS MADE THIS DRAWING OF THE FORT IN MAY 1861. (AMERICAN

HERITAGE PRINT COLLECTION)

|

In October 1861, Major Charles H. Olmstead took command of Fort

Pulaski; he would shortly be promoted to colonel. A native of Savannah,

he had been educated at the Georgia Military Academy in Marietta and was

a businessman as well as regimental adjutant when Georgia seceded.

During 1861 two lines of coastal defenses were developed in Georgia.

A series of batteries and forts were erected on the outer, "barrier,"

islands, and a series of additional defenses were constructed further

inland along major waterways. With the fall of Hilton Head Island in

November 1861, the outer line was subsequently abandoned.

During 1861 and the first six weeks of 1862, thousands of pounds of

gunpowder and ammunition were brought to the fort. In addition, Olmstead

was able to boost his artillery complement to 48 guns, including 12-inch

mortars, two English Blakely rifles, and 10-inch columbiads.

The Ida continued to visit the fort daily, bringing such

supplies as she could carry. Most of the arms, lumber, food, and

gunpowder was brought on barges towed by other steamers.

|

THIS PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN AFTER THE BOMBARDMENT OF THE FORT SHOWS A

CONFEDERATE COLUMBIAD AND A MORTAR. (LC)

|

On February 21, 1861, Captain Josiah Tattnall, a native of Savannah,

resigned from the United States Navy and became the flag officer of the

Georgia navy. Tattnall's force consisted of five small, armed

steamers—the Savannah, his flagship, and the Sampson,

Lady Davis, Resolute, and Huntress. They patrolled the

intercoastal waterway and other shallow channels between the various

marshy islands, reassuring residents who feared Federal raids. The

vessels also towed supply barges and delivered stores to Fort

Pulaski.

During the autumn of 1861, rumors reached the Confederates that

Union forces were assembling for an invasion of the South Atlantic

coast.

|

On May 27, 1861, the first Federal blockading vessel arrived in Tybee

Roads at the mouth of the Savannah River. The port was now "closed,"

although a few more blockade runners were able to dash in during the

subsequent months. After additional blockaders arrived, members of the

1st Volunteer Regiment on Tybee Island, southeast of Cockspur Island,

erected a sand fort near the lighthouse, which was at the northeastern

end of the island. The armed fort kept the blockaders at a distance and

discouraged landings by Federal forces. During the autumn of 1861,

rumors reached the Confederates that Union forces were assembling for an

invasion of the South Atlantic coast.

|

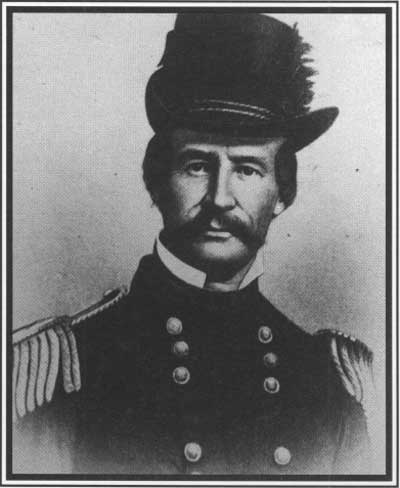

BRIGADIER GENERAL QUINCY A. GILLMORE (USAMHI)

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL THOMAS W. SHERMAN (USAMHI)

|

In early November General Robert F. Lee was appointed commander of

the newly consolidated Confederate Department of South Carolina,

Georgia, and East Florida. He arrived in South Carolina on November 7,

1861, the day that Port Royal Sound fell to a Federal army-navy combined

expedition. Lee immediately ordered Confederates to abandon Hilton Head

and Saint Phillip's Islands bordering the sound. He then began to

organize his new plan. He would abandon exposed Georgia defenses at

Darien, Brunswick, and on the Saint Marys River and had the artillery

and troops sent to Savannah. Lee planned to guard the coast with cavalry

and use the Savannah, Albany and Gulf Railroad to move troops from

Savannah south to any threatened points along the coast.

The Federal success on the South Carolina coast was the culmination

of War Department plans hatched five months earlier. Union strategy

called for blockading Confederate ports. Port Royal Sound, South

Carolina, and Fernandina, Florida, were selected as coaling stations to

sustain Federal ships in Southern waters. Commodore Samuel F. Du Pont

and Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman led the joint expedition. After

the naval bombardment drove away the defenders, infantrymen quickly

occupied Hilton Head Island. Sherman, a native Rhode Islander, was a

United States Military Academy graduate and had served as an artillery

officer. He commanded three brigades and three attached regiments. Among

Sherman's staff officers was chief engineer Captain Quincy A. Gillmore,

ordnance officer Lieutenant Horace Porter, and chief topographical

engineer Lieutenant James H. Wilson. All would have full careers during

the subsequent four years.

Sherman quickly occupied adjacent South Carolina Islands and secured

the harbors of Port Royal and Saint Helena. The day after Confederates

abandoned Hilton Head Island, the Georgia troops removed their guns from

the sand fort on Tybee Island and withdrew. Sherman and Gillmore did not

land on Tybee Island until November 25. They went to the northeast shore

and, from over a mile away, examined Fort Pulaski through telescopes.

Both men believed that they could reduce the fort from Tybee using a

combination of mortars and breaching guns, the conventional armament for

such a task. Within a week, Gillmore ordered twenty mortars, eight heavy

rifled guns, and eight columbiads.

|

GOVERNOR JOSEPH E. BROWN OF GEORGIA. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

COLONEL CHARLES H. OLMSTEAD (NPS)

|

Conventional military doctrine called for plunging mortar fire to

penetrate and disrupt the parapets and destroy the underlying casemate

arches while the smoothbore columbiads slowly shattered the brick wall.

Rifled guns were a new development, and few military experiments

deploying them against masonry fortifications had been published. Rifled

guns were reported to be more effective than smoothbore guns of

comparable caliber when fired from distances of a mile away. Gillmore

was familiar with these European reports and chose to add a few rifled

guns to his requested armament as an experiment. Although General

Sherman had little enthusiasm for the rifled guns (he believed that the

mortars and columbiads could eventually reduce the fort), he consented

to Gillmore's experiment.

In early December, Colonel Rudolph Rosa's 46th New York Infantry

occupied Tybee Island. They were soon joined by members of the 3d Rhode

Island Heavy Artillery, who mounted guns in the abandoned Confederate

sand fort at the northeastern end of the island. The 7th Connecticut,

commanded by Colonel Alfred H. Terry, joined the New Yorkers in late

December.

On the afternoon of December 29, the newly promoted Colonel Olmstead

was working with a casemated 32-pounder. Three Federals walked out on

Kings Point and, standing on the ruins of a burned house, made "defiant

and indecent gestures toward the fort." Olmstead later recalled that he

wanted to get the elevation "of our 32 Pounders for that particular

spot, and accordingly had one of the guns trained upon the group, but

without the slightest thought that there would be anything more than a

scare for the men. But the shot hit the middle man and probably tore him

to pieces. Through my glasses I could see the two others crawling up to

the body on hands and knees, and then getting up and running away as

fast as their legs could take them; its probability of its being made

again with a smooth bore gun at that distance, (a few yards short of a

mile), is infinitesimally small."

Olmstead did not know, but he had cut in half a private in the 46th

New York. The event made a big impression on the New Yorkers, many of

whom were still talking about it a month later. Rumor among the Federals

on Tybee Island was that because of the incident, Olmstead had been

promoted to colonel. Olmstead had actually received his new rank on

December 26, three days before the incident.

As Federal forces continued to strengthen their grip on the

coastal islands, Lee persevered in strengthening the inner coastal

defenses of his department.

|

As Federal forces continued to strengthen their grip on the coastal

islands, Lee persevered in strengthening the inner coastal defenses of

his department. He visited Fort Pulaski in January 1862, accompanied by

Governor Brown, Brigadier General Lawton, and a dozen other army and

naval officers. After touring the fort and viewing Olmstead's

preparations, he told the colonel, "They will make it very warm for you

with shells from that point [Goat Point and Kings Landing on western

Tybee Island] but they cannot breach your walls at that distance." Lee

knew that the greatest distance that balls could be effective against

masonry walls was 800 yards and Tybee Island was over 1,700 yards away.

Lee, perhaps unaware of experiments with the new rifled guns, was

wrong.

During his visit, Lee directed Olmstead to build sandbag traverses

between the barbette guns to protect gunners from bursting shells, to

dig ditches on the parade ground to trap rolling shells and to tear down

the wooden structures along the officers' quarters. Lee further told

Olmstead to erect blindage around the entire interior circuit of the

fort to cover the casemate doors and to cover the blindage along the

gorge with several feet of earth. After Lee's visit, Confederates

floated rafts of timber for the blindage down the river into the south

channel and up the small irrigation canal into the moat.

|

CONFEDERATE CREWS PLACED OBSTRUCTIONS IN THE SAVANNAH RIVER TO BLOCK

FEDERAL VESSELS. (FMTW)

|

In Wall's Cut, a short channel joining the New and Wright Rivers in

South Carolina, both rivers roughly parallel to the Savannah River,

Confederates had driven pilings and sunk a hulk to obstruct passage to

Federal shallow-draft vessels from Port Royal Sound. In mid-January

Union soldiers removed the pilings and secured the now-drifting hulk to

one side of the channel. Although Sherman and Du Pont initially planned

a joint expedition to bypass Fort Pulaski and take the city of Savannah

at the end of January, they called it off when naval officers objected

that the channels north of the Savannah were too shallow.

Sherman, in the meantime, had ordered Gillmore to examine Jones

Island for a possible battery site. Gillmore located a point of dry

ground on the Savannah River side of the island, an area that was but a

few inches above water at high tide. The battery site was 1,300 yards

across the island from the closest wharf site on the north shore.

Jones Island was a gelatinous mixture of mud and grass roots.

Gillmore described it:

The substratum being a semi-fluid mud, which is agitated like

jelly by the falling of even small bodies upon it, like the jumping of

men, or the ramming of earth.... Men walking over it are partially

sustained by the roots of the reeds and grass and sink in only five or

six inches. When this top support gives way or is broken through they go

down two or two and one-half feet and in some places much

farther.

|

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA, PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1865 SHORTLY AFTER THE WAR. (LC)

|

In preparation for building the wharf and walkway across the island,

soldiers on Daufuskie Island cut 10,000 pine trees during the first four

days of February. Rafts of poles, along with sandbags, were brought to

Jones Island and a wharf was completed on February 8. A corduroy pathway

across the island enabled the infantrymen to carry sandbags and planking

for a battery site across the island; they completed their work during

the night of February 10. The next two nights, during a winter

rainstorm, Federals began to move six cannon across the semifluid

island and to the battery platform. Teams of 35 men were responsible for

moving two guns at a time, guns that weighed more than two tons apiece.

First, three pairs of planks fifteen feet long, one foot wide, and three

inches thick were placed in tandem. The first gun was rolled to the end

of the first pair. The second gun was rolled onto the second pair. Then

the last pair was taken up and pulled into position in front of the

first gun. The men sunk to their knees at every step. They were soon

unable to hold the slippery, slimy planks and had to attach ropes to

drag them forward. Gillmore ordered the men to cease their efforts

about 2:00 A.M., and to resume the following night.

The same officers, with new teams of men, resumed their efforts the

next night. The wet, cold infantrymen repeated the procedure again and

again until the guns reached the battery platform. The slippery mud

offered poor traction for the wheels; frequently a gun would slip off

the plank and immediately sink to the axle. The men would carefully

lever it back onto the track and begin anew. Guns sliding off the track

frequently hit the poles and flipped them up, slamming the men into the

mud.

Despite the hardship, the six guns were in the battery before sunrise

on February 12. The site was named Battery Vulcan; the tide lapped

within eight inches of the platform. The following day Federal soldiers

saw a column of smoke across the waving marsh grass. The unsuspecting

Ida came steaming down the Savannah River on a regular visit to

Fort Pulaski. Battery Vulcan opened on her; five of the six guns

recoiled into the ooze and the Ida continued unharmed to Fort

Pulaski; she later returned to Savannah by way of Lazaretto Creek. The

soldiers remounted Vulcan's guns and enlarged the platform.

On February 20, the Union forces erected another six-gun battery,

Battery Hamilton, on the western tip of Bird Island, across the north

channel of the Savannah River from Battery Vulcan. Two days later they

sank a hulk near Decent Island in Lazaretto Creek, closing all possible

routes of resupply to Fort Pulaski. Except for an occasional courier

delivering mail and newspapers, the fort was cut off. By this time Fort

Pulaski had 48 guns, 45 in the fort and 3 mortars in outside batteries

facing Tybee Island.

Before Tybee Island's occupation, one Union observer described it as

an outer strip of sand dunes, covered with bushes and low trees,

encompassing salt marshes. "The uplands [are] covered with stunted growth

of live oak, long-leaved pine, cedar and an occasional palmetto. The

marshy strips are clothed in grasses, reeds, [and] strange looking

willows." Many of the sand hills were up to twenty feet high.

On Tybee's east and north shores there were several areas of higher

ground; the siege batteries would be constructed on the north shore. The

distance from the landing site on the northeast end of the island to the

future battery sites was two and a half miles. The last mile was low and

marshy and would be crossed by a road corduroyed with brushwood and

bundes of sticks in full view of the fort's guns.

|

BATTERY HAMILTON ON BIRD ISLAND. (FL)

|

By late February Tybee Island was occupied by the 46th New York, the

7th Connecticut, two companies of the 1st New York Volunteer Engineers,

five companies of the 8th Maine, two companies of the 3d Rhode Island

Heavy Artillery, and a few members of Lieutenant Wilson's company of

engineers. On February 21 the first piece of the Tybee Island siege

artillery arrived. Captain Gillmore would direct all of the engineer

operations for the preparation of the bombardment of Fort Pulaski. The

commander of the New York Engineers, however, was a colonel. Gillmore

was able to persuade his commander, Brigadier General Sherman, to

appoint him as acting (brevet) brigadier general in the interest of an

appropriate command structure. Needless to say, Gillmore politicked

actively for the appointment behind the scenes.

Over the next seven weeks, thirty-six guns arrived: twelve 13-inch

mortars, four 10-inch mortars, six 10-inch columbiads, four 8-inch

columbiads, five James rifles of varying calibers, and five 30-pounder

Parrott guns. The tube of the 13-inch mortar weighed 17,000 pounds; the

tube of the 10-inch columbiad weighed 15,000 pounds. Wharf facilities

for unloading the cannon tubes and carriages did not exist on Tybee

Island.

The James rifle had been developed by Rhode Island militia general

Charles T. James. Its distinctive cone-shaped projectile consisted of a

cast iron body and a cage of slanted iron ribs that started near the

middle and extended to a solid ring at the lower end. The core of the

lower half was hollow and the spaces between each of the eight ribs

communicated with the central core at their lower ends. The ribbed lower

half of the projectile was encased with soft lead and covered with tin

and a greased, sewn canvas jacket. When the gun was fired, the expanding

gasses entered the open center of the cage and swelled through the

openings between the ribs, forcing the soft lead and tin into the

grooves that the greased cam as served to lubricate. The eight elongated

ribs and openings resembled a wheel hub and Confederates in the fort

would later refer to these projectiles as "cartwheels." James

projectiles were generally double the weight of the similar smoothbore

caliber roundshot; for example, a 42-pounder James projectile weighed 84

pounds.

|

WITH WEAPONS LIKE THIS 13-INCH MORTAR, THE FEDERALS HOPED TO PUMMEL FORT

PULASKI TO OBLIVION. (USAMHI)

|

|

A WARTIME SKETCH OF TYBEE ISLAND SHOWING THE MARTELLO TOWER AND

LIGHTHOUSE. (BL)

|

The Parrott gun had been developed by Robert P. Parrott, supervisor

of the West Point Foundry. He developed a manufacturing process for cast

iron rifled cannon shortly before the Civil War. The tube was rotated

horizontally after casting and was water-cooled from the inside, which

allowed its more slowly cooling exterior to compress and strengthen the

interior. While the hot tube rotated, a wrought iron band was slipped

over the breech and, because the tube was rotating, it cooled and

clamped itself uniformly providing reinforcing strength. Projectiles for

the Parrott gun had a soft metal plate at their base to take the rifling

when fired.

Since there was no wharf for getting the guns ashore at Tybee Island,

an individual tube or gun carriage was loaded into a lighter on which a

platform had been prepared by laying thick planks across the gunwales.

The Atlantic beach of Tybee was "remarkable for its heavy surf." At high

tide, the soldiers ashore pulled the lighter toward the shore with

ropes. Others, sometimes 50 men, would tip the lighters and roll the

gun tube into the water. At low tide, up to 250 men would pull on ropes

fastened to the tube or carriage and drag it above the high tide line,

a labor that could take more than two hours.

The infantrymen then prepared a sling cart to move the guns inland.

First, the gun tube or metal carriage would be placed on a pair of skids

made of a pair of twenty-foot long foot-square timbers braced together

by three cross pieces. The men then elevated one end of the pair onto

the axle of a pair of heavy wheels. They then pulled the gun tube to the

middle of the skids. Finally, they elevated the other end of the pair

onto another pair of wheels and the sling cart was ready.

The eleven battery sites were built on the northwest shore of Tybee

Island. Construction of the batteries, gun platforms, magazines, and

splinter-proof shelters; hauling supplies; and mounting the guns and

mortars was all done at night, frequently in driving rain. All work was

covered with brush before dawn to conceal it from the Confederates. Once

a safe parapet was complete, work could continue behind it with more

freedom. Parties of men did mechanical tasks during the day; they

arrived before daylight and returned to camp after dark. By the end of

February most of the batteries were under construction. Lieutenant

Horace Porter supervised the landing of the guns and supplies and their

transport across Tybee.

Work progressed slowly. Wooden platforms were constructed to hold the

heavy guns. When the weight of the guns and their metal carriages

cracked through the platforms, soldiers added iron tracks to reinforce

the wood. Soldiers also constructed powder magazines and bombproofs and

covered them with a thick layer of protective sand. A sheltered corduroy

road connected the batteries.

Moving the guns and carriages was difficult. The men worked at night.

Teams of up to 250 men pulled the sling carts. Commands were conveyed by

whistles: stop, start, slacken the ropes. The last mile was over boggy

ground and wheels would sometimes slip into the mud and sink five feet

to their hubs, If the cart could not be levered back onto the road, the

gun tube was cut loose and rolled onto firmer ground and then reattached

to the sling cart. All of this was done in the dark without a word

spoken. Slowly, over seven weeks the soldiers completed the batteries

and placed the guns. They unloaded powder, shot, and shells at the small

island wharf. These were stored near the lighthouse and in magazines

sited near the batteries.

|

SIEGE MAP, BASED ON GILLMORE'S OFFICIAL REPORT, SHOWING THE FEDERAL

BATTERIES ON TYBEE ISLAND AND THOSE ALONG THE SAVANNAH RIVER TO THE WEST

OF FORT PULASKI. THE RIFLED GUNS THAT BREACHED THE FORT'S WALLS WERE

FIRED FROM BATTERIES SIGEL AND McCLELLAN, OVER 1,600 YARDS AWAY.

(BL)

|

|

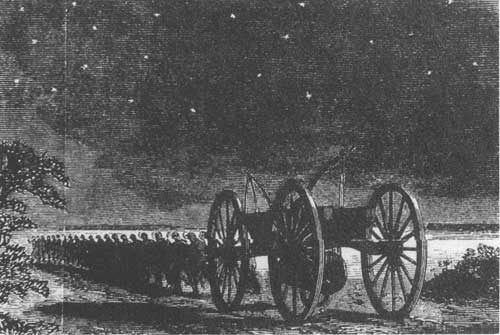

FEDERAL INFANTRYMEN HAULING A MORTAR WITH A SLING CART AT NIGHT ACROSS

TYBEE ISLAND. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

THE MARTELLO TOWER ON TYBEE ISLAND WAS BUILT ABOUT 1815. (USAMHI)

|

Gillmore had requested ten rifled guns for experimental use during

the bombardment. Familiar with published reports of European trials, he

wished to use the rifled guns against masonry Fort Pulaski. He

originally located the guns too far to the east and it was through the

cajoling of one of his engineer assistants, Horace Porter, that he

eventually came to move them to the batteries closest to the fort. Had

Gillmore initially believed the rifled guns would have been effective in

reducing the fort, he would not have spent seven weeks moving the heavy

mortars and columbiads into place before beginning the bombardment of

Pulaski.

Confederates were suspicious of the apparent inactivity on Tybee

Island. On the night of March 22 three rebels slipped across the south

channel of the Savannah River and discovered a Federal battery. At 10:00

P.M. the scouts delivered their report to Olmstead, who immediately

ordered the fort to fire at the western end of the island. At dawn, he

was unable to see if he had caused any damage. Although Pulaski's guns

caused no problems for the Federals, Olmstead now knew that the Federals

were preparing for a bombardment.

On March 30 a group from the 46th New York on a reconnaissance along

Wilmington Narrows were captured by members of the 13th Georgia. The

Yankees "made little resistance & seem perfectly well satisfied to

be captives." Several prisoners described the batteries, as well as

their armament, for the anticipated bombardment of the fort. The

Savannah Republican published the information the following day,

and couriers slipped across the marsh and through the Federal lines and

brought the information to Colonel Olmstead on April 4. By now, of

course, the isolated Confederates could do nothing but wait.

General Thomas Sherman was unpopular with many of his subordinate

officers. He also was criticized in the Northern press for his seeming

inactivity. By March 1862, he had secured Port Royal Sound, Hilton Head,

and the surrounding South Carolina islands, Tybee Island, and in early

March the port of Fernandina, Florida. His three brigades were stretched

thinly. Although he could raid the interior, he did not have sufficient

men to move inland and permanently occupy any more territory. Efforts of

the troops on Tybee had been kept from the Northern newspapers by an

embargo on letters going north. Finally, however, the War Department

gave in to popular clam or and replaced Sherman with Major General David

Hunter.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL HENRY W. BENHAM (USAMHI)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL DAVID HUNTER AS DEPICTED IN A PREWAR ILLUSTRATION.

(USAMHI)

|

Hunter had graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1822.

He had served fourteen years, resigned, and returned to serve as

paymaster during the Mexican War. A politically active abolitionist, he

had accompanied Lincoln's party to the District of Columbia for the

1861 inauguration. Slightly wounded in the Battle of First Manassas, he

had then replaced Major General John C. Fremont in Missouri, where he

brought relative order to the chaos of Fremont's regime.

Accompanying Hunter was Brigadier General Henry W. Benham, an 1837

graduate of the United States Military Academy. An engineer officer,

Benham had made his career with the army. Although highly regarded as an

engineer, he had not thus far distinguished himself in the war.

Hunter and Benham arrived at Port Royal Sound on March 31. Sherman

briefed Hunter on the state of affairs, especially the progress of works

against Fort Pulaski. Hunter immediately began reorganizing his

Department of the South, which included Federally controlled enclaves in

Georgia and Florida. He placed Benham in command of the Northern

District, which covered the same territory previously commanded by

Sherman. Sherman briefed Benham in detail about preparations against

Pulaski. Hunter then officially thanked Sherman, and shortly thereafter

Sherman departed for a new assignment in the West.

Although Sherman had not been a popular commander, Du Pont, who had

worked with him longest, reflected:

poor fellow, a more onerous, difficult, responsible, but thankless

piece of work no officer ever had to do, and none ever brought to such a

task moe complete self-sacrificing devotion—he ploughed, harrowed,

sowed, and it does seem hard that when the crop was about being

harvested he is not even allowed to participate in a secondary

position.

Since Benham's new areas of responsibility covered exactly those of

Sherman, Du Pont felt this gave "more point to the recall, or rather

making it [a] recall which was unnecessary if not unjust."

Benham immediately met with Gillmore to review plans for the

bombardment of Fort Pulaski. Gillmore remained Benham's chief engineer;

Porter, his chief of ordinance. On April 1, Benham inspected the works

on Tybee Island. He pressed Gillmore to complete the Tybee batteries;

Benham was concerned about the lack of additional batteries at other

sites that could provide concentric fire against the fort from opposite

quarters. He ordered a mortar battery on the eastern end of Long Island

and began reviewing the possibilities of battery sites on the South

Carolina islands north of Fort Pulaski.

The Confederates continued preparing for the coming bombardment. By

now the blindage against many of the casemate doors had been covered

with heaped dirt. In early April the garrison pulled down the colonnade

in front of the officers' quarters and mess rooms. They deepened the

trenches on the parade. Squat piles of sandbag traverses sat between the

parapet guns. One Confederate recorded in his diary that he put his

trust "in God, ourselves, the mosquitos & sand flies."

|

THIS 1863 PHOTOGRAPH SHOWS FORT PULASKI AFTER THE SURRENDER. THE 3D

RHODE ISLAND HEAVY ARTILLERY ARE AT PRACTICE WITH SMOOTHBORE AND SIEGE

GUNS. (USAMHI)

|

On the afternoon of April 9, a small party of Confederates slipped

out of Fort Pulaski and rowed to Long Island, a mile and a half from the

fort, where they discovered the mortar battery. Disabling the mortar by

driving a tenpenny nail into the fuse hole, they returned to the fort

with shells, powder, fuses, and other artillery supplies.

Beginning in April the Connecticut and New York men began intensive

drills on the guns. Instructed by the Rhode Island artillerymen, they

practiced everything but firing. The infantrymen were under a distinct

disadvantage because they were unable to get the range of their pieces

before the bombardment opened. Many of the Federal officers were not

optimistic about the success of the bombardment and feared that if it

dragged on for long, a Confederate ironclad, then known to be under

construction in Savannah, might pass Batteries Vulcan and Hamilton and

jeopardize the Federal endeavor.

|

|