|

|

FORTIFICATION IN THE CIVIL WAR

Fort Pulaski was part of a large system of fortifications that by

1860 guarded virtually every important harbor in the United States. As

such, it reflected an outlook that for nearly two centuries dominated

American military policy. With the army small and scattered over the

frontier, coastal fortification in fact was about as much military

policy as the country was willing to implement.

The first act of the first English colonists in Virginia in 1607 was

to build a fort. As the colonies expanded in the following centuries, so

did their penchant for fortifying any place deemed threatened or useful

as a refuge. By the time the Americans declared their independence from

Britain in 1776, they were decidedly fortification-minded. This outlook

was reinforced after independence by the Founding Fathers' distaste for

professional armies, as well as anxiety about threats from Britain or

other European nations. Forts offered physical strength at threatened

points and would bolster the militia who would rush to meet an attack.

The navy was the country's first line of defense, and forts protected

naval refuges.

|

THE NORTHWEST CORNER OF FORT PULASKI DURING UNION OCCUPATION. (USAMHI)

|

The first fortification program of the new nation was a series of

simple earthworks erected to meet a threat of war with France in the

1790s. A decade later, increasing tensions with Britain called for a

more sophisticated set of installations, the first public work partly

conducted by engineers American in birth and training—the early

graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The war that erupted in 1812 between the United States and Britain

saw few American successes, except for repulses of the enemy from

fortified places such as Craney Island in Virginia and Fort McHenry in

Maryland. The country was invaded several times, and only forts and

fieldworks offered any bright spots in a dismal story. The legacy of the

War of 1812 dominated military policy thereafter, in two

respects—the country was vulnerable to invasion, and forts answered

that danger.

Over the next half-century, army engineers erected works at every

major and many minor harbors along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and,

after 1850, on the Pacific as well. Like Pulaski, they were

sophisticated exercises in geometry and masonry, expressions of

principles worked out in European siege warfare and perfected in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They were no match, however, for

advances in military and industrial technology happening in the

nineteenth century.

|

THE FIERCE UNION BOMBARDMENT OF FORT PULASKI RENDERED IT—AND

MASONRY FORTS LIKE IT—OBSOLETE. (USAMHI)

|

The forts were built to withstand solid shot fired by smoothbore

cannons. The advent of explosive rounds fired by rifled guns spelled

their doom. As Union gunners demonstrated at Fort Pulaski in 1862,

rifled shot could penetrate fort walls, exploding within amid a shower

of splinters. The smoking holes in Pulaski's walls looked out on the end

of an era.

There was some attempt to reinforce the forts to meet the new

realities after the Civil War, but by 1875 they were mostly abandoned.

Advances in metallurgy, explosives, gun design, and shipbuilding went on

apace, and in the 1880s the country began another attempt to fortify

itself. Modern gun emplacements appeared at harbors around the country,

but they nearly always were outmoded before completion. Still the

country turned to fortifications with new types in the 1930s and

1940s.

Forts, however, were yesterday's answer to tomorrow's challenges,

which now came from above. They received their ultimate insult during

the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in 1941, after which it was

apparent that fixed coastal emplacements—whether Fort Pulaski or

something newer—no longer met the need. The last expression of

fort-mindedness was the NIKE missile antiaircraft installations of the

1950s, mostly abandoned within a decade.

Fort Pulaski exemplifies an important and long-standing part of

America's military past. Its dramatically sudden obsolescence in 1862

reflected more than the end of an era, however. It signaled the birth of

modern warfare.

— David A. Clary

|

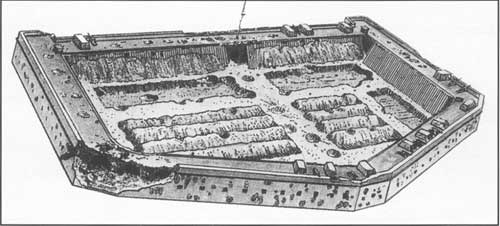

SKETCH OF FORT PULASKI AT THE TIME OF ITS SURRENDER ON APRIL 11, 1862.

(NPS)

|

|

Hunter initially planned to open on the fort on April 9, but

torrential rain fell all day. He postponed the bombardment. The day was

spent rushing preparations for an opening the next day. Bags of powder

for the 13-inch mortars had not arrived; the men would have to measure

powder with empty vegetable cans, pour it loose into the guns, and

adjust it in the chamber before firing. Columbiad shells were bound to

wooden sabots, or disks, with strips of tent canvas; the sabots were at

the end of the shell opposite the fuse hole and served to orient the

ball, fuse away from the charge, before firing. That night the Federals

suddenly discovered they had no fuse plugs for their 10-inch mortar

shells. The Connecticut men sat up during the night whittling mortar

fuses; after seven weeks' exertions hauling guns and building batteries,

they were content to sit and whittle.

The Federals on Tybee Island had constructed eleven batteries

containing 36 artillery pieces. Benham later remarked that Gillmore had

named the batteries for "the persons most prominent or most likely to

be so, in political or military service." The batteries, their

armament, and distance from Fort Pulaski are listed below:

| Battery |

Armament |

Distance to

Pulaski, yds. |

| Stanton | 3 13-inch mortars | 3,400 |

| Grant | 3 13-inch mortars | 3,200 |

| Lyon | 3 10-inch mortars | 3,100 |

| Lincoln | 3 8-inch mortars | 3,045 |

| Burnside | 1 13-inch mortar | 2,750 |

| Sherman | 3 13-inch mortars | 2.650 |

| Halleck | 2 13-inch mortars | 2,400 |

| Scott | 3 10-inch columbiads | 1,740 |

| 18-inch columbiad |

|

| Sigel | 5 30-pounder Parrotts | 1,670 |

| 1 48-pounder James rifle |

|

| (old 24-pounder) |

|

| McClellan | 2 84-pounder James rifles | 1,650 |

| (old 42 pounder) |

|

| 2 64-pounder James rifles |

|

| (old 32 pounder) |

|

| Totten | 4 10 inch mortars | 1,650 |

|

A UNION SOLDIER POSES WITH A 10" COLUMBIAD IN VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

Close to each battery was a service magazine filled with sufficient

powder for two days' firing. Nine hundred shot and shells for each gun

were also stored in the service magazines. A depot magazine near the

lighthouse held an additional 3,600 barrels of powder. Traverses

separated the guns in each battery, protecting the gun crews from

lateral explosions. Each battery had splinterproofs for the shifts of

men not on duty. Each battery had its own well. The advanced batteries

were all connected by trenches for safe communication. A bombproof

surgery was erected at Goat Point, near Lazaretto Creek, also the site

of the four batteries closest to Fort Pulaski.

That night Gillmore issued his final instructions, coordinating the

role of each battery. The eastern mortar batteries and Battery Totten

were to drop their shells on the parapet above the casemates to

penetrate the earth and collapse the underlying arches. Columbiads in

Batteries Lyon and Lincoln were to fire over the southeast wall and hit

the interior of the the gorge and north face. Batteries Scott and Lyon's

columbiads were to help silence the barbette guns and then direct their

fire at the pan coupé between the south and southeast faces. The

rifled guns of Battery Sigel were to incapacitate the barbette guns,

then direct their efforts to breach the pan coupé. The rifled

guns in Battery McClellan were to fire directly at the pan coupé

to attempt to breach the wall.

That night Hunter and Benham sailed from Port Royal Sound to Tybee;

Hunter anchored near the lighthouse early on the morning of April 10.

Hunter had invited Du Pont to accompany them, but the commodore regarded

it as "an army affair" at which he had no business. While Benham made

his final inspection, Hunter remained aboard his boat to prepare his

summons for Olmstead's surrender. Horace Porter noted the arrival of the

two new "stars," a reference to their shoulder straps of rank, and noted

that they were "as impatient for the fray as Roman ladies for the

commencements of a gladiatorial combat."

|

THE LIGHTHOUSE ON TYBEE ISLAND. (USAMHI)

|

As light dawned at 5:30 on the morning of April 10 Confederates in

Fort Pulaski discovered that mounds of sand at the west end of Tybee

Island had been leveled, brush cut away, and four batteries stood where

dunes had been visible before. Only part of Pulaski's artillery—ten

barbette guns, six casemate guns, and two mortars—could fire on

Tybee. Only four barbette guns and three casemate guns could bear on

Goat Point, site of the Federal rifled guns, four columbiads, and four

mortars.

At dawn Hunter sent Lieutenant Wilson over to the fort to demand its

surrender. Four sailors rowed Wilson over to Cockspur Island; Wilson sat

in the bow and an additional sailor in the stern held aloft a white

flag. Hunter's terms of surrender read:

I hereby demand of you the immediate surrender and restoration of

Fort Pulaski to the authority and possession of the United States. This

demand is made with a view of avoiding, if possible, the effusion of

blood which must result from the bombardment and attack now in readiness

to be opened.

The number, caliber, and completeness of the batteries surrounding

you leave no doubt as to what must result in case of your refusal; and

as the defense, however obstinate, must eventually succumb to the

assailing force at my disposal, it is hoped you may see fit to avert the

useless waste of life.

Wilson's orders allowed him to wait only thirty minutes for a reply.

A Confederate lieutenant, also with a flag of truce, politely received

Wilson at the south wharf. Leaving Wilson with his boat, the Confederate

returned to the fort. He rejoined Wilson exactly thirty minutes later

with Colonel Olmstead's sealed reply. With the Federal batteries

unmasked, Olmstead knew the moment he had awaited for two months was now

arrived. He used his thirty minutes to assemble his men, post them to

their guns, serve ammunition, and prepare the hospital. The colonel's

message to Hunter was brief:

I have to acknowledge receipt of your communication of this date

demanding the unconditional surrender of Fort Pulaski. In reply I can

only say that I am here to defend the fort, not to surrender it. I have

the honor to be, very respectively, your obedient servant,

Chas. H. Olmstead

Colonel, First Volunteer Regiment of Georgia, commanding Post

|

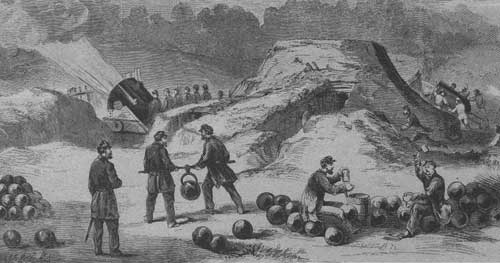

MORTARS FIRE FROM BATTERY STANTON ON TYBEE ISLAND DURING THE BOMBARDMENT

OF FORT PULASKI ON APRIL 10, 1862. (FL)

|

Hunter read Olmstead's reply, then quickly sent an aide to Porter

with the message, "The General sends his compliments and desires you

open the ball at once." At 8:15 A.M., Porter aimed and fired the first

gun, a 13-inch mortar in Battery Halleck. A member of the 7th

Connecticut gun crew chalked on the side of the shell, "A nutmeg from

Connecticut; can you furnish a grater?" The shell moved in a graceful

arc over Pulaski and exploded on its descent beyond the fort.

Confederate Lieutenant Henry Freeman offered the first response with a

32-pounder casemate gun. Initial firing on each side was slow and wild

but each soon learned the range of his targets. Within an hour, the

Federal batteries were firing three rounds a minute. The northwest shore

of Tybee Island was a line of smoke punctuated with blasts of flame. The

reverberation of fifty cannons from both sides made the ground shake. As

the morning passed, the guns, especially those of the Federals, gained

greater accuracy.

|

A HARPERS WEEKLY ILLUSTRATION OF THE ATTACK ON FORT PULASKI.

|

Colonel Rosa and members of his 46th New York manned the guns of

Battery Sigel. Rosa disregarded his firing instructions, mounted the

parapet, drew his sword, and directed all six guns to fire in one

volley. Continuing to fire in volley with great cheers, the men made up

in enthusiasm what they lacked in accuracy. Rosa was unable to control

his men, ignored his orders, and "was making bad work of it" when

Gillmore ordered him away. The New Yorkers refused to work their guns

without their colonel, so Gillmore sent them all packing and replaced

them with sailors, trained on artillery, from Du Pont's

Wabash.

Shortly before noon, the halyard of Pulaski's flagpole was cut by

a shell and the flag fluttered down. Thinking the fort had surrendered,

Federal soldiers mounted their pararpets and cheered their

victory.

|

Shortly before noon, the halyard of Pulaski's flagpole was cut by a

shell and the flag fluttered down. Thinking the fort had surrendered,

Federal soldiers mounted their parapets and cheered their victory.

Confederates soon removed the tangled flag from the parapet and

remounted it on a temporary staff—a cannon rammer—in the

northeast angle of the fort. A volley at the Federals sent them

scampering into their batteries and fire immediately resumed.

Confederate shells directed against the middle batteries frequently

fell short, splashing into the river. The marshes behind the breaching

batteries at Goat Point caught many Confederate mortar rounds, which

sank before exploding.

Inside the fort, a shot came through a casemate embrasure early in

the day, dismounting a gun and severely wounding one man. The James

projectiles were flaking brick. Olmstead wrote, "Thirteen inch

mortar shells, columbiad shells, Parrott shells, and rifle shots were

shrieking through the air in every direction, while the ear was deafened

by the tremendous explosions that followed each other without cessation."

After three hours of firing three casemate guns lay dismounted. Most of

the Confederate parapet guns, on the sea face, were dismounted by the

end of the first day. "The effect upon the fortification was becoming

disastrous," the colonel observed. Later during the first day of the

bombardment, Olmstead was in a casemate when a columbiad shot from Goat

Point struck the fort while the wall was still intact and "bulged the

bricks on the inside, a significant fact that left little doubt of what

the ultimate result would be." By the end of the first day's

bombardment, the wall had been flaked away and only two to four feet of

brick remained.

|

A CURRIER AND IVES RENDITION OF THE BOMBARDMENT. (NPS)

|

|

THIS THEODORE DAVIS SKETCH DEPICTS LIEUTENANT HORACE PORTER DIRECTING

MORTAR FIRE ON APRIL 11. (AMERICAN HERITAGE COLLECTION)

|

During the night of the first day's bombardment, Olmstead went out to

inspect the exterior of the fort:

It was worse then disheartening, the pan-coupe at the

south-east angle was entirely breached while above, on the rampart,

the parapet had been shot away and an 8-inch gun, the muzzle of which

was gone, hung trembling over the verge. The two adjacent casemates were

rapidly approaching the same ruined condition; masses of broken masonry

nearly filled the moat. . . . [In] the interior of the three

casemates... dismounted guns lay like logs among the bricks.

To his wife, Olmstead wrote that the angle opposite the Goat Point

batteries was shattered and that he knew that "another day would breach

it entirely."

Federal fire continued during the night, one round every ten or

fifteen minute's to prevent the defenders from sleeping. Early the next

morning, both sides resumed in earnest. Only three Confederate parapet

guns bore on Tybee and only one could reach the Goat Point batteries.

Benham and his staff, standing on a dune behind Battery Lyon, observed

progress through a large tripod telescope. They saw the growing pile of

rubble overflowing the moat. Shells from rifled gun's penetrated deeper

and deeper, fracturing the brick wall. Solid shot from the columbiad's

smashed the masonry, dislodging great slides of brick into the moat

amid rust-colored clouds. One Federal observed that with each shot that

struck the wall "a cart-load of brick [would] fall into the ditch." By

10:00 A.M. Benham could see the thinnest wall of a recess arch at the

angle. An hour or so later the next arch was visible. Toward noon three

casemate arches were opened. Gillmore now ordered the guns to begin

concentrating on the next adjacent casemate wall along the southeast

wall.

By now great masses of brick, loosened the previous day, filled the

moat. With the first visible opening, Tybee Island rang with "cheer

after cheer." "What a scream ran down the line when the first hole

appeared! Every shot that enlarged it was hailed with another yell."

Another Federal officer reported that "soon a huge opening appeared in

the wall through which a two horse wagon might have been driven."

Excited gunners redoubled their rate of fire and it seemed as if "even

the solid earth shook with the long thunder peal."

|

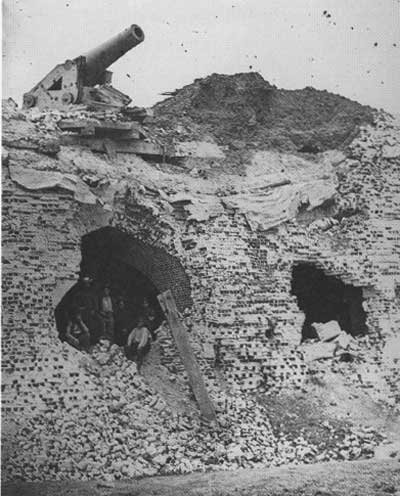

THE BREACHED PAN COUPÉ AS VIEWED FROM THE SOUTH OF THE

FORT. (USAMHI)

|

|

A BLAKELY GUN SITS ON THE BRICK-STREWN BARBEETTE. (USAMHI)

|

It was now apparent that the face of the southeast wall would be

peeled off. With the moat filled with brick debris, an assault party,

aided by ladders, could scramble over the nibble and into the fort and

overpower the garrison, the strength of which Federals had learned

earlier from deserters. Benham's aide, Major Charles G. Halpine, was

assigned to lead the assault. Knowing that two Irish companies were in

the fort, the Irishman Halpine wanted to lead the column. Scheduled for

April 12, the assault would prove unnecessary.

During the morning of the second day a Confederate shell burst over a

gun in Battery McClellan mortally wounding Private Thomas Campbell,

Company H, of the 3d Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. Horace Porter

observed that "his face was burned perfectly black, his left side torn

away and his left leg taken off. He lived three hours, spoke about his

wife and family, seized hold of his captain's hand and died." Campbell

was the only Federal fatality of the bombardment.

Inside Pulaski, Olmstead realized that "it was simply a question of a

few hours as to whether we should yield or be blown into perdition by

our own powder." By now seven barbette guns were disabled, the traverses

were "giving way," the west side of the fort was a wreck, and the

southeast angle was badly breached, allowing "free access of every shot

to our magazine." The magazine, in the northwest corner, was protected

by a large traverse; however, around 1:00 P.M. a shell entered an opened

casemate at the southeast angle, passed across the parade, and through

the top of the traverse to explode in the entrance way of the magazine.

The magazine was piled high with barrels of powder—twenty tons. The

magazine filled with light and smoke but did not explode. Olmstead knew

that the next such shot could blow up the fort beneath them all. He

realized he had reached the end. Beyond any help from the "Confederate

Authorities," he "did not feel warranted in exposing the garrison to the

hazard of the blowing up of our main magazine. . . . There are times

when a soldier must hold his position 'to the last extremity,' which

means extermination, but this was not one of them, there was no

end to be gained by continued resistance."

|

HEAVY TIMBERS OR BLINDAGE COVERED THE CONFEDERATE LIVING QUARTERS,

PROTECTING THEM FROM EXPLODING SHELLS. (NPS)

|

|

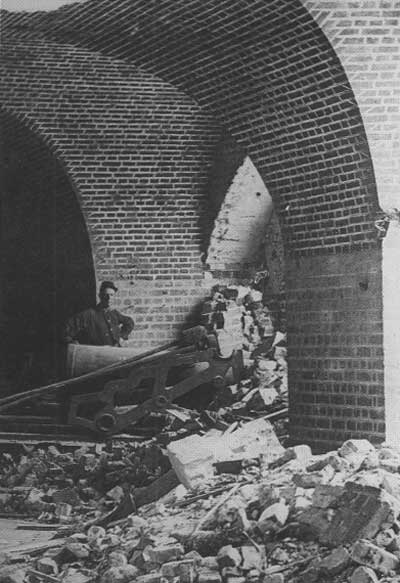

INTERIOR OF ONE OF THE RUINED CASEMENTS AFTER THE SURRENDER OF FORT

PULASKI. (LC)

|

Confederate fire ceased at 2:00 P.M., the Confederate flag was

lowered, and a white flag was raised. All but two parapet guns were

disabled; two casemate guns bearing on Tybee Island were dismounted, The

outer wall covering two casemates had been destroyed and that of the

adjoining casemate on either side was crumbling. Incredibly, only three

Confederates—A. Shaw, T. J. Moullon, and Isaac Ames—were

seriously wounded.

Benham and members of his staff gathered at Lazaretto Creek to find a

boat to take them over to Pulaski. A violent storm had blown throughout

the eleventh and the soldiers were unable to get their boat away.

Gillmore had joined Benham's party to cross to Cockspur Island and

accept the surrender; he left and found some of the Wabash

sailors, who, understanding tides and currents, quickly rowed him to

the fort. He entered, had the gates shut, and met with Olmstead for an

hour arranging the terms of surrender. When the other Federal officers,

led by Halpine, were finally able to reach Cockspur Island, Gillmore

kept them waiting outside the fort until he had the signed surrender

document:

ARTICLE 1. The fort, armament, and garrison to be surrendered at

once to the forces of the United States.

ART 2. The officers and men of the garrison to be allowed to take

with them all their private effects, such as clothing, bedding, books,

&c.; this not to include private weapons.

ART 3. The sick and wounded, under charge of the hospital steward

of the garrison, to be sent up under a flag of truce to the Confederate

lines, and at the same time the men to be allowed to send up any letters

they may desire, subject to the inspection of a Federal officer.

Gillmore left the fort as Halpine and his party entered to take

charge of the surrender of the fort and receive the officers' swords and

take possession of the flag.

|

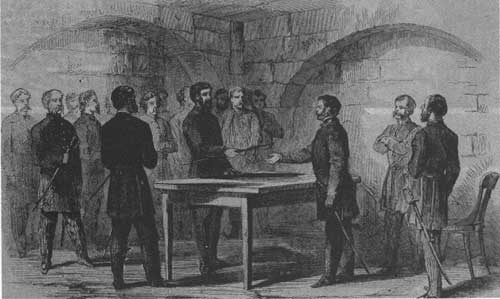

COLONEL OLMSTEAD AND HIS OFFICERS SURRENDER TO MAJOR HALPINE, ASSISTANT

ADJUTANT-GENERAL TO GENERAL HUNTER. (FL)

|

|

ILLUSTRATION OF FORT PULASKI AFTER ITS SURRENDER. (BL)

|

Twenty-six-year-old Colonel Olmstead handled the surrender

gracefully. He impressed all as "a man of superior character . . .

reflective countenance, and mild and gentlemanly manners." Once the

garrison had been assembled to stack arms, Olmsted asked if he might be

spared ordering his men to disarm. Halpine gave the necessary orders.

Next the officers surrendered their swords and sidearms. Olmstead

stepped forward first, placed his sword on the table, and said, "I yield

my sword, but I trust I have not disgraced it." The other officers came

forward according to rank and laid their swords on the table, "most of

them making a slight inclination of the head and showing good bearing."

A few sullenly threw their swords down. One said, "I hope to be able to

resume it to fight for the same cause." Another officer claimed to

have no sword and offered to surrender his sash, which was refused.

After the ceremony was finished, the officers adjourned to the mess

room where food and wine were served. Feelings of awkwardness lifted

during the informal conversation. One Confederate officer joked, "Why

you are only four and we three hundred and fifty; I think we ought to

take you." Another Confederate sarcastically asked a Connecticut officer

about wooden nutmeg's. Pointing to a 10-inch columbiad shot, the

Northerner answered, "We don't make them out of wood any longer."

Altogether, 361 Confederates surrendered, 24 of whom were officers.

Eighteen sick or wounded Confederates would remain in the fort; the

remainder were sent north to prison. Contrary to the surrender term's,

the prisoners were not allowed to take their private effects with them

into captivity. Those remaining in the hospital were not returned to

Confederate authorities but, when well enough, were sent north to

prison. The officers and men were exchanged in August and September 1862

and again served the Confederacy. Years after the war, Colonel Olmstead

was offered the opportunity to meet with Gillmore; the Georgian declined

because he felt that Gillmore had allowed Hunter to violate the terms of

surrender.

|

INTERIOR OF THE FORT AS IT LOOKED ON APRIL 12, THE DAY AFTER ITS

BOMBARDMENT. (BL)

|

|

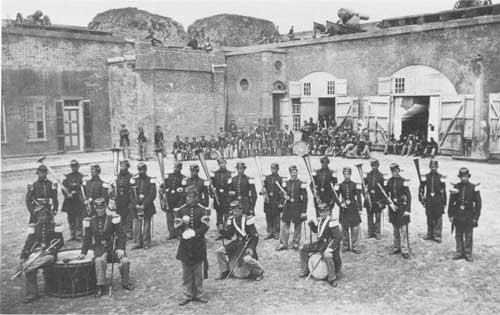

THE BAND OF THE 48TH NEW YORK VOLUNTEER INFANTRY INSIDE THE OCCUPIED

FORT. (USAMHI)

|

The 7th Connecticut immediately occupied the fort. Lieutenant Colonel

Joseph Hawley, of the 7th Connecticut, retrieved the white surrender

flag and sent it to his wife. Officers cut the Confederate flag into

fragments and sent them home as souvenirs of their victory. It had been

a year since the bombardment of Fort Sumter; Horace Porter wrote his

sister, "Sumter is avenged!" Along with members of the 1st New York

Volunteer Engineers, the Connecticut men began repairing the breach and

by the end of April the repair work was well under way; it was completed

the following month. Guns were removed from Tybee Island and shipped

northward, some destined for the siege of Fort Sumter. Batteries Vulcan

and Hamilton on the Savannah River were disarmed. On June 4, the 48th

New York replaced the 7th Connecticut; they remained for almost a year.

In June 1863, Pulaski's garrison was reduced.

Federals had fired over five thousand projectiles; the Confederates,

a third that many. Gillmore observed that the 84-pound solid James

projectiles had penetrated up to twenty-six inches. The lighter James

projectiles had penetrated twenty inches. Most of the damage was caused

by three James rifles—two 84-pounders and one 64-pounder. The

Parrott projectiles penetrated up to eighteen inches; however, they

frequently wobbled and flipped end over end and were of little use in

the bombardment. The columbiad's had less penetrating power but were

most effective, "crushing out immense masses of masonry." Fewer than 10

percent of the mortar rounds even hit the fort. The mortars caused none

of the anticipated damage to the casemate arches. As effective as the

Federal artillery was, it would have been even more so had the crews

been given opportunity to drill and fire their artillery pieces before

the actual bombardment.

|

UNION SOLDIERS PROUDLY POSE IN ONE OF THE GAPING HOLES CAUSED BY THE

CONSTANT BOMBARDMENT. (LC)

|

|

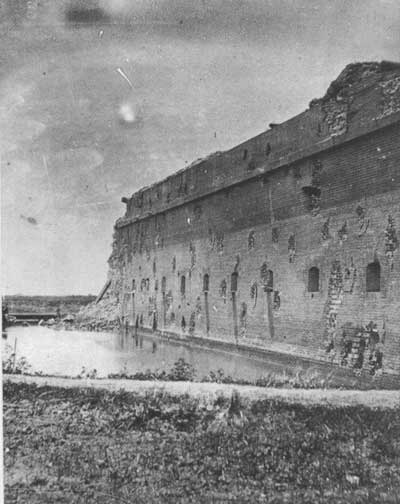

THE SOUTHEASTERN WALL WITH THE BREACHED PAN COUPÉ ON THE

LEFT. RUBBLE NEARLY FILLS THE MOAT AT THE POINT OF THE BREACH. (USAMHI)

|

The effectiveness of rifled artillery meant that future sieges and

bombardments could be prepared for far more easily. Instead of seven

weeks of heavy labor preparing batteries and moving heavy mortars and

columbiad's lighter rifled guns could be more quickly maneuvered into

position. Rifled guns would play a major role in Gillmore's next

endeavor—the siege and bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston

Harbor.

The use of rifled artillery revolutionized siege warfare. Before the

reduction of Fort Pulaski, masonry forts were regarded as impregnable.

Major General David Hunter best summarized the significance of what

happened on Cockspur Island:

The result of this bombardment must cause, I am convinced, a

change in the construction of fortifications as radical as that

foreshadowed in naval architecture by the conflict between the

Monitor and Merrimac. No works of stone or brick can resist

the impact of rifled artillery of heavy caliber.

After its capture, Fort Pulaski played little active role in the war.

It closed Savannah as a Confederate port. Held by a reduced garrison, it

would gain brief noteriety during 1864. In June, the Confederate

commander in Charleston, South Carolina, Major General Samuel Jones,

attempting to relieve the bombardment of his city, placed five generals

and forty-five field officers in quarters in parts of the city that had

been under constant shelling. He then notified Major General John G.

Foster, commander of the Department of the South. Foster retaliated

immediately, requested a similar number of Confederate prisoners of

equal rank, and placed them in a stockade on Morris Island under the

gun's of Fort Sumter. Jones soon realized that his strategy had served

no useful end; however, it suddenly became difficult to move the

prisoners from Charleston. Major General William T. Sherman had begun

his campaign into northwest Georgia and the Confederate prisoner of war

camp in Andersonville was believed to be among his possible objectives.

Hundreds of Federal prisoners were transferred elsewhere, and many began

to arrive daily in Charleston. Jones's problem suddenly changed when a

yellow fever epidemic erupted in the city. He was able now to transfer

his prisoners—officers to Columbia and men to Florence, South

Carolina—without authorization from his superiors.

Foster had accumulated 600 Rebel prisoners before the crisis passed.

Forty-nine were hospitalized, four had escaped, two had taken the

Oath of Allegiance to the United States, two had been exchanged, four

were dead, six were imprisoned elsewhere for attempting to escape, and

thirteen were "unaccounted for." Foster sent his 520 bedraggled men to

Fort Pulaski for imprisonment. Shoeless, dressed in rags, they were ill

with dysentery and pneumonia.

Colonel Philip P. Brown, of the 157th New York, now commanded the

fort. Knowing the prisoners were coming, he requisitioned blankets,

clothing, and firewood. His requests were ignored. Confined in the

casemates within an iron prison cage, the Confederates had neither

blankets nor decent clothes. Coal was absent and firewood scarce;

cookstoves could be lit only once a day. Colonel Brown fed the

prisoner's as well as he could from the garrison stores, for which he

was censured by his commanding general.

After conditions in Andersonville prison became known, Federal

authorities retaliated. On December 15 Brown was ordered to impose a

starvation ration: a quarter pound of bread, ten ounces of cornmeal, and

a half pint of pickles daily and one ounce of salt every five days.

Brown was instructed to allow the prisoners to purchase additional food

from sutlers, but they had no money to do so. Further, Brown was not

allowed to receive money from Confederate authorities.

Winter was unusually severe. The prisoners subsisted on their bread,

corn-meal, and pickles. Rats and an occasional stray dog or cat added to

their diet. There were no blankets and no fires. The men began to

succumb to scurvy in mid-January.

|

THE SOUTHWEST CORNER OF FORT PULASKI, 1863. (USAMHI)

|

Savannah fell to Union authorities on December 21, 1864, and by

January 21, 1865, Fort Pulaski was assigned to Major General Cuvier

Grover's District of Savannah. Six days later, the district's medical

director inspected the fort and the prisoners were immediately returned

to full rations. Four hundred and sixty-five—all that

survived—were sent north on March 5, 1865, to the Federal prison at

Fort Delaware.

In May 1865, the captured president of the Confederate States,

Jefferson Davis, was briefly imprisoned in Fort Pulaski. In command of

the detail escorting Davis northward was Brigadier General James H.

Wilson, who had served during the preparations to isolate, besiege, and

bombard Fort Pulaski earlier in the war. During the summer three

Confederate cabinet officers—Secretary of State Robert M. T.

Hunter, Secretary of the Treasury George A. Trenholm, and Secretary of

War James H. Seddon—were imprisoned in the fort. Confederate

assistant secretary of war John A. Campbell, Alabama governor Andrew B.

Moore, South Carolina governor Andrew G. Magrath, Florida governor

Alexander K. Allison, and Florida senator David L. Yulee were all

confined during 1865.

|

PAINTING OF TODAY'S FORT PULASKI FROM THE WEST SHOWS THE PLAN OF THE

FORT. STRUCTURES IN THE DEMILUNE WERE BUILT DECADES AFTER THE CIVIL WAR.

(NPS)

|

|

|