|

SURRENDER IN THE CENTER

By midafternoon Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles who commanded a division in

Bragg's corps, sensed the futility of further attacks on the heavily

defended Hornets' Nest sector. He thus instructed staff officers to

collect artillery in an attempt to hammer the position into submission.

Likewise, Beauregard began to shift forces, including several batteries

of artillery, from the left to the center, in response to reports of

heavy concentrations of Union forces blocking the Southern advance

there. In addition, individual Confederate battery commanders, without

instructions by superiors, personally redeployed their field batteries

to engage the stubborn Federal defense holding the Union center. The

result of this hour and a half of shifting and deploying cannon was that

by 4:30 all or parts of eleven Southern batteries had been assembled

opposite the Hornets' Nest. Tradition, including General Ruggles

himself, has placed the number at sixty-two, but fifty-three is probably

a more accurate number of cannon employed at any one time in the

resulting bombardment.

The thirty- to forty-five-minute barrage, heavy as it was in this

largest concentration of field artillery yet experienced on any North

American battlefield, may not have been as spectacular as often

portrayed. The letters and diaries of several Confederate artillerymen

whose batteries participated failed to mention the event. One ranking

artillery officer, in postwar years, implied that the cannonade lasted

only a few minutes. It did succeed, however, in driving off the

remaining Federal batteries supporting the Union Hornets' Nest line.

|

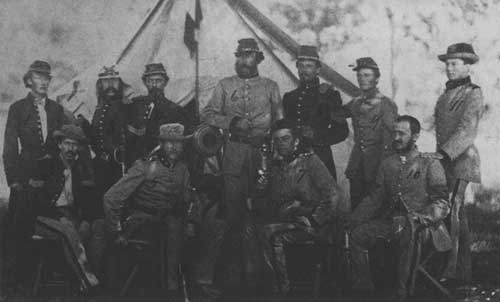

OFFICERS AND NONCOMMISSIONED OFFICERS OF CAPTAIN ARTHUR M. RUTHLEDGE'S

TENNESSEE BATTERY. THIS BATTERY JOINED ELEMENTS OF TEN ADDITIONAL

CONFEDERATE BATTERIES TO BOMBARD THE HORNETS' NEST IN THE LATE AFTERNOON

OF APRIL 6, 1862. (TENNESSEE STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES)

|

Although a significant portion of the Federal left under General

Hurlbut made a stubborn temporary stand at Wicker Field, by 4:00 P.M.

Grant's left was making a rapid fighting withdrawal toward Pittsburg

Landing. This move exposed Prentiss's left flank in the Hornets' Nest,

forcing him to refuse his left, which now faced to the southeast and

engaged the Confederates swarming up the River road. A similar

retirement occurred on William Wallace's right by John McClernand's

Union division, leaving the Union forces holding the Federal center

isolated. General Wallace was stunned to learn of the breakup of Colonel

Sweeny's brigade on his right. Many of Sweeny's men had retreated with

McClernand's troops. Sweeny's breakup permitted the Confederates moving

on the left to turn the right flank of Wallace's line and penetrate into

the Federal rear. At 5:00 both Wallace and Prentiss dispatched orders

for their men to withdraw. But already, thousands of Southerners were

advancing rapidly around both Wallace's and Prentiss's exposed flanks to

threaten a complete envelopment of the Union center. In the ensuing

confusion, some Union troops managed to shoot their way out and escape

toward the landing through a narrow outlet along the Corinth road, but

others never received orders.

About 5:30, after six hours of heavy fighting, the Hornets Nest

defense finally collapsed. Most of the Federal units were surrendered

individually by their field officers. William Wallace had been mortally

wounded and left for dead on the field. Meanwhile, General Prentiss

surrendered in a heavily wooded area dubbed "Hell's Hollow." In all,

Confederates captured some 2,250 men. As the triumphant Southerners sent

up a loud cheer, a still defiant Benjamin Prentiss said, "Yell, boys,

you have a right to shout for you have this day captured the bravest

brigade in the United States Army."

As white flags of surrender were raised throughout the smoke-filled

forest, some Federal units attempting to escape still continued to

fight. The situation was both confusing and deadly for several minutes.

Other Union soldiers who had surrendered defiantly smashed their muskets

against trees so that the weapons would not fall into enemy hands. Col.

William T. Shaw, commanding the 14th Iowa Infantry, was nearly knocked

insensible by a low branch as he attempted to escape. When he regained

his wits, he looked up to see a major of the 9th Mississippi standing

over him saying, "I think you will have to surrender." Meanwhile, a

couple of Confederate cavalrymen snatched the flag of the 12th Iowa and

dragged it unceremoniously through the mud.

Neither in his abbreviated battle report nor later in his memoirs did

General Grant provide much insight or comment on the day-long stand made

by the defenders of the Hornets' Nest. But the courageous stand made by

Wallace's and Prentiss's men had gained the surviving Federal forces

precious time. Since 4 P.M. the Hornets' Nest had occupied the full

attention of the majority of Confederate forces still effectively

engaged on the field. Now, with darkness casting a shadow over the

field, the hour was getting late for Beauregard's Confederates.

|

|