|

VI. Types of Forest History and Dynamics

The lodgepole forests in Crater Lake National Park have several

apparent types of stand history: Type 1) Those seral lodgepole forests

which are rapidly replaced by fir and hemlock need to be considered as a

part of the larger complex of fir-hemlock forests. At any one time, part

of this complex is in mature fir-hemlock forest, part in seral lodgepole

stands, and part in transition (Fig. 1).

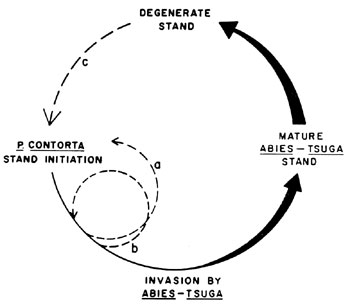

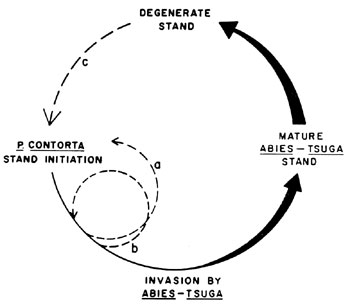

Figure 1. A proposed model of stand development in areas supporting

seral P. contorta forest on pumice soils. Heavy arcs indicate

phases in which intense fires are unlikely. Solid fine curves indicate

phases in which intense fires are more probable. Broken lines signify

fires. Fire types a and c are intense enough to initiate a new P.

contorta stand. Fire type b may initiate a new age class or only

burn the understory and tree reproduction. (from Zeigler, 1978).

Intense fires, which kill the fir and hemlock, create new lodgepole

forests, which may then develop into fir-hemlock with time. The

lodgepole reproduces poorly in these dense seral forests and beetle kill

hastens its demise. Litter is heavy; a reburn would probably kill most

of the lodgepole but would also produce a new lodgepole forest. In most

stands of this type, the major age class originated after white man

arrived. From historical records it seems that a larger proportion of

the area which can potentially support fir-hemlock is now in lodgepole

than there was in primeval conditions. This resulted from the many fires

in 1855 to 1900, some of which burned in mature forest. Type 2) Some

areas which can support fir-hemlock are invaded by trees only slowly

after forest destruction by fire, probably due to a relatively dense

herbaceous cover. Gradually the lodgepole pine increases in number, with

most reproduction being near older trees, forming islands of forest in

which fir and hemlock become established. These tree islands gradually

spread into the meadow between, and, probably after two or more

generations of lodgepole without a major disturbance, a closed forest

may form. In the meantime, however, some individual tree islands were

probably destroyed or thinned by local fires and by bark beetles,

delaying forest closure. Tree growth is very rapid once trees finally

become established, and they reach beetle-susceptible size at a

relatively young age. Type 3) In some lower elevation areas, contiguous

to the ponderosa pine forest, periodic ground fires probably maintained

a mixed forest of lodgepole, white pine, fir and hemlock. Fuel loads are

low, and the burns were probably small or patchy, and of low intensity.

Large trees, even lodgepoles, were scarred without dying, but most of

the reproduction in the burns would have been killed, and lodgepole

reproduction increased in the openings. One fire, which increased the

fuel load as dead trees fell, probably led to a greater chance of a

later reburn there. If a long enough time passed without fire, an

intense fire, killing most trees, could probably have been supported by

the accumulated fuel. Lodgepole re-invasion could have led to another

forest maintained by periodic ground fires. The burning interval between

the only two fires recorded on scars was 30 years, but now, 80 years

later, fuel loads still appear too low to allow other than patchy fires.

Type 4) Some areas appear to be lodgepole pine climax, where fir and

hemlock rarely establish. In the better sites, an open or patchy

lodgepole forest gradually may become a quite dense thicket, stopping

lodgepole reproduction at least in spots. In the patchy phase fires were

probably small or of low intensity due to discontinuous or light cover

of litter. These small fires and beetle kills delayed the development of

closed forest. After the forest closed, and most likely following heavy

beetle kill, intense fires occurred, killing all trees and beginning the

cycle again. After 75 years of fire protection, some of these forests

have developed densities and fuel loads which are very conducive to

intense fire and probably equal or exceed the maximum present under

primeval conditions. Type 5) Some climax lodgepole forests are very

sparse in all layers, and grow in habitats which appear incapable of

supporting denser forest. Fire would be confined to very small patches

of continuous fuel. It seems unlikely that extensive fires of any type

could have been supported. Reproduction occurs more or less

continuously. Beetle kill or local fires remove the older trees;

however, some with heavy mistletoe survive longer than any trees in

other communities. In these forests, fire effects appear minor, the

stands are in more or less a steady state, and further stand development

will be a process of primary succession, occurring only over many

generations of trees.

VII. Plant Communities in Lodgepole Pine Forest

Eleven communities were defined in the lodgepole pine forest. These

communities are named after the apparent climax tree species and

dominant shrubs and herbaceous species. A key for the identification of

the communities in the field accompanies this report as Appendix B. The

general distribution of these communities is shown in a type map

(Appendix C). We strongly urge that the map be used only for general

orientation and that the key be used when deciding management policies

for any particular location in the field.

In general, we found that no one community can be said to result

entirely from man's activities, though some types apparently prospered

as a result of the numerous fires that accompanied the white ' s arrival

in the area. One community appears to have experienced fairly frequent

ground fires, as well as quite severe fires. Contrary to the popular

belief that lodgepole pine is usually seral, we have found three

communities where lodgepole pine is the only tree even in old stands,

and is reproducing in large numbers.

Brief community descriptions are given below. Accompanying data are

presented in Appendices E, F and G. Included in these descriptions are

what we believe to be the disturbance histories and the consequences of

a fire at the present time. For more complete community description and

the facts upon which this summary is based the reader is referred to

Robert Zeigler's Masters Thesis. The number in parentheses beside the

community name corresponds to the number of the community on the type

map (Appendix C).

(1) Incense Cedar/Manzanita

This community is found on steep rocky slopes along Annie Creek

Valley. The vegetation includes sparse forest with numerous herbs and

shrubs growing among the rocks. Ages indicate that the fires that

probably infrequently burned this type likely originated in lodgepole

stands downslope from it.

(2) Lodgepole Pine/Bitterbrush/Sedge

Stands of this type are found in the northeast quarter of the Park

between Sharp Peak and Desert Creek at elevations between 1650 m and

1750 m. The herbaceous vegetation is similar to community 3, with the

addition of a shrub layer of bitterbrush and, to a lesser extent,

rabbitbrush goldenweed. These generally open stands are composed of

almost pure lodgepole pine. The apparent successful reproduction by

lodgepole pine in the absence of fire, and that all charcoal is from

lodgepole pine, indicate that this community is a true lodgepole

climax.

There is evidence of past mountain pine beetle activity, though

litter accumulation is still fairly light. Because of the patchy nature

of the ground cover, light ground fires were probably not extensive.

Fairly infrequent intense fires probably recycled the stand after heavy

fuel buildup. Most of the areas occupied by this community are probably

incapable of supporting either kind of fire at present.

(3) Lodgepole Pine/Sedge-Needlegrass

This community is found on flat areas and depressions with deep

pumice and/or scoria deposits at elevations from 1570 m to 2000 m. The

largest examples are in Pumice Flat, around the Pumice Desert and on the

west side of Sand Creek. The ground vegetation in this type is

characteristically depauperate, consisting mainly of a sparse, patchy

cover of sedges and grasses. There are very few, if any, shrubs. Though

there may be some hemlock and white pine near other communities,

lodgepole pine is usually the only tree species present in all layers.

Therefore, this community is considered a true lodgepole climax.

Most stands were extensively thinned by mountain pine beetle

epidemics in the first half of the century. The thinned stands support

relatively vigorous lodgepole regeneration. Most older trees are

severely infected with dwarf mistletoe. Considering the present fairly

abundant reproduction, this will probably lead to stands being heavily

infected with dwarf mistletoe; this was likely also the case in the

primeval forest.

Stands in this community probably burned only rarely and then only

over small areas The litter accumulation, even after 70+ years without

fire, is very patchy with islands of heavy fuels separated by large

areas of mineral soil Openings in the stand permitting lodgepole

regeneration probably resulted from beetle kills. Any fire starting in

this type would probably be quite small--limited to one snag or a

locally heavy collection of litter. That fire was relatively unimportant

in the community in pre-white man times is further supported by the

great ages of the stands and the scarcity of charcoal on the forest

floor. All charcoal is from lodgepole pine.

(4) Lodgepole Pine/Sedge-Lupine

This third lodgepole pine climax community is found in extensive

areas about the Park. It is most accessible on the west side of Sand

Creek. Other large stands may be seen northeast of Cascade Spring,

southwest of Sharp Peak, west of Timber Crater and southeast of Bald

Crater. Stands of this type, found between 1700 m and 1980 m, are

recognized by the presence of pine (Anderson's) lupine. In some areas

goldenweed and squaw current may be present.

Areas supporting this type were probably visited by intense fires in

the past as suggested by the presence of only one or two age classes in

all but 2 of 13 sample plots. Recent high bark beetle activity and

apparent ice breakage have led to very heavy litter accumulations in

some areas. This natural buildup has been increased by locally dense

reproduction, resulting in areas of apparently very high flamability.

These areas are also characteristically severely infected with dwarf

mistletoe. It seems likely that areas such as these would have burned

before now without fire suppression. Fire in the area would probably

result in nearly 100% tree mortality with a short term reduction in

fuel. Dwarf mistletoe in the stand would be eliminated or greatly

reduced. As mortality from the fire fell the fuel load would again

increase. Another fire, consuming this post-fire fuel and corresponding

reproduction, would probably permit the establishment of a stand of

vigorously growing trees in an open meadow-like environment.

The closed, highly flammable areas of this community are found

between the North Entrance Road and Timber Crater and at the

southeastern end of the Pinnacles Valley. Open stands, whose origins are

likely those hypothesized above, are found in the upper western

Pinnacles Valley, the area southwest of Sharp Peak, and west and north

of Desert Cone.

(5) White Fir /California Brome-Lupine

This community is found only in a small area northeast of the

Panhandle and west of Sun Creek at elevation 1460 m. White fir is the

dominant tree in the understory. There is extreme accumulation of litter

from past bark beetle epidemics in some areas. Age data indicate that

this type existed prior to the white man's arrival in the area.

Following 1855, fires may have increased the area occupied by this type.

A fire at present would probably destroy most of the stand in some

areas, with lodgepole pine re-establishing itself following fire.

(6) Subalpine Fir/Collomia-Peavine

This community is found in very wet areas near the headwaters of

Bybee Creek and Copeland Creek at about 1700 m. The community is best

distinguished by the presence of collomia and peavine, though very wet

sites may contain a rich flora. Lodgepole pine grows very rapidly on

these sites and both Shasta red fir and subalpine fir occur. The

dynamics of this type are probably quite similar to the subalpine

fir/goldenweed/aster-blue wildrye type (no. 7 below), though tree

invasion is even slower because of intense competition with herbaceous

species.

(7) Subalpine Fir/Goldenweed/Aster-Blue Wildrye

This relatively lush seral community is found between 1540 and 1920 m

in the vicinity of streams and at the base of steep ridges. The most

extensive stands are on the west slope of Mount Mazama, Munson Valley,

and along upper Sand Creek. Smaller stands occur near Sphagnum Bog,

Crater Springs and Pole Bridge Creek. Floristically, this type differs

from others in the presence of Cascade aster, blue wildrye, Green's

rabbitbrush and/or Rydberg's penstemon. Subalpine fir is also present in

almost all areas. Rather than being a true forest, the community is a

forest-meadow mosaic. Patches of relatively dense trees of all sizes are

separated by relatively lush meadows of lupines, grasses and sedges. The

islands of tree reproduction appear to be slowly spreading into the

meadow areas. Heavy litter accumulations occur only in the tree islands.

In older, nearly closed stands, such as those found in upper Munson

Valley, tree mortality from mountain pine beetle has been and continues

to be quite high among older, larger trees.

Most of these areas were burned before 1900 by ranchers, to improve

grazing for their herds. Age analysis indicates that most of the west

slope stands are of post-white man origin while those in Munson Valley

contain pre-white man age classes. Charcoal data indicate that some

earlier stands contained predominantly fir and hemlock. Fires in this

type, at present, would probably be limited to a few tree " islands'"

and the intervening meadow-like areas. In the primeval forest, intense

fires through nearly closed forests of this type probably resulted in

very open forest-meadow mosaics. These mosaics gradually closed over

several generations of trees, with closure retarded or temporarily

reversed by periodic light or small fires. The closed forests either

burned again or developed to pure fir-hemlock stands.

(8) Shasta Fir-Mountain Hemlock/Sedge-Lupine

This widespread seral community is found between 1690 m and 2080 m

through out the Park. Extensive stands may be found in the northwest

quarter of the Park, on the slopes of Timber Crater and in Castle Creek

Valley. This community is recognized by the presence of pine and/or

broadleaf lupine in an understory of conspicuous and apparently vigorous

fir and hemlock reproduction.

Bark beetle activity and breakage at galls on the main stems of

trees have contributed to a heavy accumulation of lodgepole pine litter.

Fires in this community would probably result in nearly 100% tree

mortality and a post-fire forest of lodgepole pine. However, litter

loads would again be high within a decade or two after the fire as

fire-killed trees fell.

Age analysis of stands comprising this community reveals that only

half of the stands contain trees which germinated before 1855. Charcoal

from some of the stands indicates that the sites were occupied earlier

by fir and hemlock forests. In addition, many stands contain old,

unburned logs and stumps that were obviously quite old firs and hemlocks

from a previous forest. Some stands contain surviving large trees of

these species. Other stands of almost pure medium-sized fir and hemlock

contain a few very large lodgepole pines and have considerable lodgepole

mortality on the forest floor.

These data and observations in this community suggest that:

1) A natural cycle exists where lodgepole pine forests are created

from mature fir-hemlock forests by fire. Lodgepole pine forests created

in this manner may be maintained as lodgepole by repeated fire for a

period of time before developing to fir-hemlock again (Fig. 1).

2) Fires caused by white man in the late 19th century increased the

area of this community and created areas of lodgepole that were

previously in fir-hemlock. Thus, the area of this community is larger

now than in the primeval situation.

(9) Mixed Conifer/Manzanita-Bitterbrush/Sedge

This community is found only in steep slopes northeast of Mazama Rock

at elevations around 1770 m. It is similar in structure and composition

to the Mixed Conifer/Manzanita community. It apparently experiences

periodic ground fire. Severe fires are probably infrequent.

(10) Mountain Hemlock/Grouse Huckleberry

This seral community, found between 1600 m and 1770 m, is recognized

by patches of grouse huckleberry in an otherwise depauperate understory.

Tree reproduction is mixed hemlock and fir with the former usually

dominant. The litter accumulation, age structure and apparent history of

this type are similar to the Fir-Hemlock/Sedge-Lupine community (number

8).

(11) Mixed Conifer/Manzanita

This is one of the communities of lodgepole pine that probably

experiences fairly frequent ground fires. It grows in small areas

throughout the Park between elevations of 1570 and 1900 m. The sparse

understory is dominated by pinemat manzanita and/or greenleaf manzanita.

Tree reproduction is well represented by Shasta red fir, western white

pine and lodgepole pine. Ponderosa pine may be found in stands on the

east side of the Park. A sizeable stand is found along Highway 62 north

of the Panhandle. Other stands may be found along the East Fork of Annie

Creek, the east side of Sand Creek, northeast of Mazama Rock and west of

Bald Crater.

These stands are typically quite old and heavily infected with dwarf

mistletoe. Bark beetle mortality is apparently continuous. Many trees

exhibit fire scars with the interval between scars on white pine being

between 30 and 40 years. This community probably experiences several

light fires be tween the infrequent severe fires which would be

responsible for stand destruction. These light, patchy fires would allow

continued reproduction by lodgepole pine.

|