|

Denali

A History of the Denali - Mount McKinley, Region, Alaska Historic Resource Study of Denali National Park and Preserve |

|

Chapter 5:

CHARLES SHELDON AND THE MOUNT MCKINLEY PARK MOVEMENT

A native of Vermont, where as a youth his interest in natural history could flourish, Charles Sheldon went on to Yale and bright prospects in the profession of law. Then the family business supporting this progression collapsed. But with a good start and his own talent and determination Sheldon became a success in the rail-road business. He served as general manager of a railroad in Mexico from 1898 to 1902. During this time his investments in Mexican mining allowed him to retire from active business in 1903 at age 35. From that time on his avocation as a hunter-naturalist would become his public-service vocation in a life dedicated to preserving North American game animals. [1]

It was in Mexico that Sheldon's particular interest in the mountain sheep of North America first took hold. Learning that Dr. Edward W. Nelson of the U.S. Biological Survey (forerunner of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) had done biological studies in Mexico, Sheldon contacted him in 1904. Sheldon's association with Doctor Nelson and his equally distinguished colleague Dr. C. Hart Merriam became a moving force in Sheldon's life. He decided to devote his natural history interests to furthering the work of the Biological Survey, especially as it related to the preservation of game animals and their habitats. Nelson and Merriam became his mentors in the mammology and specimen-collection work that eventually brought him to the Denali region in 1906 to study the white Dali sheep of the North. [2]

From all accounts and from original documents that trace his altruistic career Charles Sheldon emerges as a loyal, dependable, and friendly man. In his scientific work his search for facts was indefatigable. As a seasoned man of affairs he was astute in the ways of politics and could spot a rascal at a distance. He did not suffer fools, but friends he never forgot—no matter their station in life. He was indeed of the Eastern elite, but he was no elitist, as his enduring friendships with and favors from and to Alaskan friends demonstrate.

Physically Sheldon was a sturdy 5 feet 10 inches tall, weighing a hard 170 pounds. He was inured to hardship as the price of the wilderness adventures he savored and followed to the day of his death in 1928 at age 60. Harry Karstens and others of his Alaskan associates admired Sheldon as a fellow woodsman, a man to be trusted on any trail no matter how long and tough it might be. This was a compliment bestowed rarely on people from the Outside.

Teddy Roosevelt, the archetype of the strenuous life in the turn-of-the-century era when Sheldon rose to prominence, had this to say about his fellow hunter-naturalist in a review of Sheldon's book The Wilderness of the Upper Yukon (1911):

Mr. Sheldon is not only a first-class hunter and naturalist but passionately devoted to all that is beautiful in nature, and he has the literary taste and ability to etch his landscapes into his narratives, so they give to the reader something of the feeling that he must have had when he saw them—and that this is no mean feat is evident to everyone who realizes how uncommonly dreary most writing about landscape is, for the average writer either treats the matter with utter bareness, or, what is worse, indulges at much length in "fine writing" of the abhorrently florid and prolix type.

Mr. Sheldon hunted in the tremendous Northern wilderness of snow-field and torrent, of scalped mountain and frowning pine forest; and in all the world there is no scenery grander in its lonely desolation than that which he portrays. He is no holiday hunter. Like Stewart Edward White, he is as skillful and self-reliant a woodsman and a mountaineer as an old-time trapper, and he always hunts alone. The chase of the Northern mountain sheep, followed in such manner, means a test of every real hunter's quality—marksmanship, hardihood and endurance, nerve and skill as a cragsman, keen eyesight, and high ability as still hunter and stalker. Mr. Sheldon possesses them all. Leaving camp by himself, with a couple of crackers and a piece of chocolate and perhaps a little tea in his pocket, he would climb the mountains until at last he saw his game, and then might have to spend twenty-four hours in the approach, sleeping out over-night and not returning to camp until late the following evening, when he would stagger downhill through the long sub-arctic dusk with the head, hide, and some of the meat of his game on his back. . . .

But the most important part of Mr. Sheldon's book is that which relates not to hunting but to natural history. No professional biologist has worked out the problems connected with these Northern mountain sheep as he has done. He shows that they are of one species; a showing that would have been most unexpected a few years ago, for at one extreme this species becomes the black so-called Stone's sheep, and at the other the pure white, so-called Dali's sheep. Yet as Mr. Sheldon shows in his maps, his description, and his figures, the two kinds grade into one another without a break, the form midway between having already been described as Fannin's sheep. The working out of this fact is a matter of note. But still more notable is his description of the life history of the sheep from the standpoint of its relations with its foes—the wolf, lynx, wolverine, and war eagle. [3]

Sheldon was not only a hunter-naturalist and gifted writer, he was also a man of broad philosophical perspective. The preservation of wild places and the wildlife inhabiting them, to which he devoted the specific actions of his public life, had a much broader objective. He believed that "the continued vigor and moral strength of the American people," would, in a closing America, be maintained only if the Nation's "forests, mountains, waterways, parks, roadways, and other open spaces" continued to provide opportunities for both energetic and contemplative outdoor recreation. Every generation of Americans, he asserted, must have these opportunities. They were part of the character-forming American heritage. It was incumbent on the federal government, through the various agencies that manage such landscapes, to aggressively provide for the health and welfare of the people through a national recreation policy that would foster and coordinate this critical public service, ramifying its benefits through all jurisdictions from federal to state to local. The particular points of this policy, as he sketched it about 1920, included a comprehensive recreation plan encompassing the great national parks and forests and wildlife preserves, as well as smaller regional and near-urban spaces for easy access for all; educational programs to guide the conservation of these open spaces; and the exclusion of economic development in the National Parks. [4]

In taking this stance, Sheldon joined the national debate then raging in American conservation policy. He was too practical a man and too politically attuned to espouse an extreme preservation position. At the same time, he differed from the prevalent utilitarian notion that all natural resources should be developed for economic ends. He believed that chosen landscapes should be maintained in pristine condition as reminders and places of generational reliving of the frontier experience that had driven America's history. His was a balanced concept that paired the Progressive conservation movement, organized around the "wise-use" ideas of Gifford Pinchot, with the older ideas of George Perkins Marsh and John Muir, which asserted man's obligations to the natural environment and the intangible benefits to be derived from Nature's unaltered works. In such balance would be found both the Nation's economic health and its spiritual salvation. [5]

Teddy Roosevelt's description of Charles Sheldon's field work on the Upper Yukon suffices for understanding his mode of operation at Denali. During his first visit in the summer of 1906, he and Harry Karstens, along with packer Jack Haydon of Dawson, traveled almost continuously with packhorses, living largely off the game that they hunted. Their rudimentary equipage and provisions allowed them to set up and fold camp with minimum effort. Typically, when a campsite was chosen after a day of travel, Sheldon took off alone while the men performed camp duties. He hiked over the ridges and into the lower elevations of the mountains noting everything he saw—game trails and other signs, and the animals themselves. He killed as necessary for meat. They entered the Denali piedmont and valley via Eureka ("about twenty tents and a few cabins"). At the head of Moose Creek they reached the crest of the outer hills overlooking lower Muldrow Glacier and McKinley River. Here ". . . Denali and the Alaska Range suddenly burst into view ahead, apparently very near."

I can never forget my sensations at the sight. No description could convey any suggestion of it. I have seen the mountain panoramas of the Alaska coast and the Yukon Territory. In the opinion of many able judges the St. Elias range is one of the most glorious masses of mountain scenery in the world. I had viewed St. Elias and the adjacent mountains the previous year, but compared with the view now before my eyes they seemed almost insignificant.

Three miles below lay the glacial bar of the Muldrow Branch of the McKinley Fork, fringed on both sides by narrow lines of timber, its swift torrents rushing through many channels. Beyond, along the north side of the main Alaska Range, is a belt of bare rolling hills ten or twelve miles wide, forming a vast piedmont plateau dotted with exquisite little lakes. The foothill mountains, 6,000 or 7,000 feet in altitude and now free from snow, extend in a series of five or six ranges parallel to the main snow-covered range on the south. Carved by glaciers, eroded by the elements, furrowed by canyons and ravines, hollowed by cirques, and rich in contrasting colors, they form an appropriate foreground to the main range.

Denali—a majestic dome which from some points of view seems to present an unbroken skyline—rises to an altitude of 20,300 feet, with a mantle of snow and ice reaching down for 14,000 feet. Towering above all others, in its stupendous immensity it dominates the picture. Nearby on the west stands Mount Foraker, more than 17,000 feet in altitude, flanked on both sides by peaks of 10,000 to 13,000 feet that extend in a ragged snowy line as far as the eye can see. [6]

Sheldon began his survey for sheep at the foot of the Peters Glacier moraine. Several days there produced no results, so the party got ready to move northeasterly along the piedmont, paralleling the range. The mountain loomed directly above the Peters Glacier camp, and Sheldon could not resist it. He had found old camps left by Judge Wickersham and Doctor Cook, so he must try at least the lower reaches of the mountain. On July 27 he climbed up the spur that curved around the east side of the glacier, then zigzagged upwards through soft snow to a point several thousand feet above the plain where the walls became vertical:

. . . As the clouds lifted, leaving the vast snow-mantled mountain clear, I seated myself and gazed for more than an hour on the sublime panorama. There was not a breath of wind, and no sound except the faint murmur of the creek far below, and the cannonading and crashing roar of avalanches thundering down the mountain walls.

Great masses of ice kept constantly breaking away from far up near the summit. Starting slowly at first, they increased in momentum and size, accumulating large bodies of snow and ice, some of which during the rapidity of the descent were ground into swirling clouds resembling the spray of cataracts. When the sliding material pitched off the glacier cap and struck the bare walls below, enormous fragments of rock were dislodged and carried along with the mass, which finally fell on the dumping ground of the moraine. Then, before the clouds of snow had disappeared from the path of the avalanche, the rumbling of the echoes died away and silence was again supreme. During the four hours that I was there, nineteen avalanches fell—some of them of enormous proportions. Eleven were near by and visible throughout their descent.

Behind me reared the tremendous glacier cap in all its immensity. To my left Peters Glacier filled the deep valley between the north face of the mountain and a high adjoining range; to my right was the northeast ridge of Denali; and, as far as I could see, on both sides of me were the spired crestlines of the outside ranges.

Directly below us was the newly formed moraine of Peters Glacier, the glacier itself appearing like a huge white reptile winding along the west side. Not yet smoothed by the elements, this moraine was one confused mass of drumlins, kettle holes, eskers and kames. Many miniature lakes glistened in the depressions; patches of green grass and dwarf willows along the water courses, with flowers and lichens, added a wealth of color to its desolate surface. Along the base of the mountain was the dumping ground of the avalanches—a wild disorder of debris.

Through bisected ranges of mountains I could see the rolling piedmont plateau, filled with hundreds of bright lakes, and still beyond could look over the vast wilderness of low relief all clothed in timber, until the vision was lost in the wavy outlines of rolling country merging into the horizon. Far to the northwest Lake Minchumina, reflecting the sun, fairly shone out of the dark timber-clad area surrounding it.

Alone in an unknown wilderness hundreds of miles from civilization and high on one of the world's most imposing mountains, I was deeply moved by the stupendous mass of the great upheaval, the vast extent of the wild areas below, the chaos of the unfinished surfaces still in process of moulding, and by the crash and roar of the mighty avalanches.

The sun was low; a dark shadowy mantle was cast over the wild desolate areas below; the skyline of the great mountain burned with a golden glow; distant snowy peaks glistened white above sombre-colored slopes not touched by the light of the sun, which still bathed the wide forested region of the north. A huge avalanche ploughed the mountainside not a hundred and fifty yards to my left, while clouds of snow swept about me.

Awakening to a realization that I had been and was still in a path of danger, I slowly made the descent. [7]

Frustrated by the lack of sheep, Sheldon and his men packed up and moved on, keeping close to the range. The ridges near the lower Muldrow were also barren of sheep. So they kept on toward the Toklat River headwaters. The plateau reminded Sheldon of "a well-stocked cattle ranch in the West, except that here cattle were replaced by caribou." [8]

A painful carbuncle on Sheldon's ankle forced a 3-day halt, even with Karstens' pocket knife field surgery. Sheldon accepted this delay with equanimity, for the weather was perfect, and the layover gave him a chance to enjoy the smaller creatures:

The abundant ground squirrels amused us, marmots whistled on the moraine, Canada jays flew about, the tree sparrows and intermediate sparrows sang continually, and waxwings and northern shrikes were particularly plentiful. White-tailed ptarmigan with broods of chicks were near; the wing-beats of ravens passing overhead hissed through the air; Arctic terns flew gracefully over the meadows; and the golden eagles soared above the ridges. Old bear diggings were everywhere, but no large animal was seen except a big bull caribou which Haydon saw on the moraine. Our numerous traps failed to capture any mice, nor did we see any sign of these small mammals, always so interesting to the faunal naturalist. [9]

Finally, on August 5, with walking staff in hand, Sheldon and the others made their move for the Toklat headwaters. A nearby sheep trail and a white object in the distance cheered Sheldon, despite the pain of his affliction:

Sheep at last! I thought. But the field glasses revealed a grizzly bear walking along smelling the ground for squirrels or pawing a moment for a mouse. Under the bright sun its body color appeared to be pure white, its legs brown. It seemed utterly indifferent to the eagle, which again and again darted at it. Continuing, it often broke into a short run, pausing at times and throwing up its head to sniff the air—always searching for food. [10]

At last, at camp that night, Sheldon "looked toward the top of a mountain directly ahead and on a grassy space just below the summit saw twelve sheep, which the glasses showed to be ewes and lambs. This was my first sight of sheep in the Alaska Range; how elated I felt." [11]

Finding timber at the main forks of the Toklat, under the rise of Divide Mountain, the expedition set up its main camp. For 10 days Sheldon roamed the nearby crags finding sheep in numbers "more abundant than I had ever imagined." Groups of 60 or 70 ewes and lambs were not unusual. But even here, Sheldon's objects—to study the life history of these sheep and to collect representative specimens—could not be fulfilled, for not a ram did he find on the Toklat

On August 16, with Sheldon's time running short for return to the Yukon and steamboat passage out, Sheldon and Haydon packed one horse and rode east toward the mountains of the Teklanika drainage. On that day of transit, with sheep on every mountain, Sheldon estimated that he saw at least 800 sheep, more likely 1,000. Excepting a band of young rams on the Toklat-Teklanika divide, they were all ewes and lambs. Disgusted, Sheldon sent Haydon back with the horses and, alone, made camp near Sable Pass.

Next day, on the north end of Cathedral Mountain, which he named as he scanned it, Sheldon saw a group of sheep high up. Getting closer and using the glasses, he saw that they were rams. Closer yet he could distinguish their big horns—these were old rams, nine of them with "strikingly big horns." Despite the day's long hike Sheldon instantly began the stalk, crawling across the flats visible to the sheep, crossing swollen glacial streams, and finally getting into the cover of the mountain flanks where he could climb rapidly. A squall of wind and rain heightened his sense of wild excitement in the magnificent mountain panorama. Low clouds made the crestlines seem suspended over a broken horizon.

The final hour and a half of the stalk required all of his patience, skill, and strategy—inching along when in view, moving only when the rams had their heads down feeding or were turned away, absolutely silent during his progress on knees and elbows over rough, loose rock. Finally he reached the brink of the canyon beyond which the rams were feeding. The rain had become a drizzle, but the strong wind still favored him:

Finding a slight depression at the edge I crept into it and lay on my back. Then slowly revolving to a position with my feet forward, I waited a few moments to steady my nerves. My two-hundred-yard sight had been pushed up, and watching my opportunity, I slowly rose to a sitting position, elbows on knees. Not a ram had seen or suspected me. I carefully aimed at a ram standing broadside near the edge of the canyon, realizing that the success of my long arduous trip would be determined the next moment. I pulled the trigger and as the shot echoed from the rocky walls, the ram fell and tried to rise, but could not. His back was broken. The others sprang into alert attitudes and looked in all directions. I fired at another standing on the brink, apparently looking directly at me. At the shot, he fell and rolled into the canyon. Then a ram with big massive wrinkled horns dashed out from the band and, heading in my direction, ran down into the canyon. The others immediately followed, but one paused at the brink and, as I fired, dropped and rolled below. Another turned and was running upward as I fired and missed him.

For a moment, after I had put a fresh clip of cartridges in the rifle and pushed down the sight, all was silence. I remained motionless. Then came a slight sound of falling rocks and the big ram appeared, rushing directly toward me—coming so fast that he crossed the slope to the brink of the canyon before I could get a bead on him. He dashed down the steep opposite side and came running up only twenty feet away, when I fired. He kept on, but fell at the edge of the canyon behind me. Two other big rams were following, but when I fired at him, they separated. One ran up the canyon and as he paused a moment, I killed him in his tracks. The other had gone below but at the sound of the shot, started back. When he reached the top I fired and he rolled down near the bottom. A smaller one ran up the slope near by, but I paid no attention to him.

Then another appeared on the edge of the canyon, where the first two had been shot. He had returned from the bottom of the canyon and seemed confused as to which way to run. Since his horns were large, I pushed up the two-hundred-yard sight, and brought him down. Another then came running out of the canyon directly toward me, and turned up the slope. As his horns were not very large, I let him go. The remaining three rams must have ascended through the bottom of the canyon for they were not seen again.

Seven fine rams had been killed with eight shots—and by one who is an indifferent marksman! My trip had quickly turned from disappointment to success. [12]

After dispatching the wounded animals Sheldon descended the mountain in darkness and reached camp about midnight. He made soup and tea and sat by the fire to dry his clothes—wet since the morning's first stream ford. Then he worked on his journal notes to record "the success of that memorable day." Now followed several days of intensive labor by Sheldon, still alone: butchering the sheep and hauling meat, skins, and skulls down the mountain; treating skins and skulls for specimen preservation; noting stomach contents, physical condition, and measurements. On the third night after the hunt, Karstens appeared with the horses, and next day the lot was hauled to the main camp. Sheldon's main work of the summer was done. He had tracked the Dall sheep in their Denali haunts and gathered specimens that could be analyzed by scientists and mounted for display in the American Museum of Natural History.

A flight of cranes winging south brought mixed emotions. Their urgency sparked his own not to miss the last steamboat before freezeup. At the same time, he knew that he had just begun to understand the Dall sheep and the larger world of the Denali region. Karstens had become a real companion—not only was he a master of all practical matters of camp life and travel in the wilderness, but also "brimful of good nature" and agreeably interested and helpful in the work that Sheldon was doing. [13] It would be hard to leave this life of freedom in a place that so fully requited Sheldon's spiritual, intellectual, and physical ideals.

But he would come back. The weeks of frustrating search for the big rams had become a symbol of all he did not know.

I realized that the life history [of the white sheep] could not be learned without a much longer stay among them and determined to return and devote a year to their study. With this in view I planned to revisit the region, build a substantial cabin just below my old camp on the Toklat, and remain there through the winter, summer, and early fall. [14]

The return trip through the nearly deserted camps of the Kantishna and down that river and the Tanana got him back to the Yukon in time. The Dawson-bound steamer Lavelle Young. crowded to bursting in that last-chance-out season, picked him up at Tanana Station, a cluster of saloons, gambling houses, and trading company warehouses, with an Indian village on one end and the Army's Fort Gibbon on the other. From Dawson another steamboat took him to Whitehorse, where he boarded the White Pass train to Skagway, whence he departed by ocean steamer on October 22.

Sheldon's year in residence in the lee of Denali, from about August 1, 1907, to June 11, 1908, [15] allowed systematic, season-by-season observation of the wildlife whose mysteries he had started to plumb the previous summer. From the home cabin that he and Karstens built at timberline on Toklat River, Sheldon ventured forth in good weather and bad. On long trips, say to the Teklanika Mountains, he and Karstens would set up camp and Sheldon, alone or sometimes with Karstens as hiking companion, would tramp the country noting the distribution and movements of the animals. He aimed to get a definitive picture of the life history of Dall sheep. During that pursuit he also gathered facts on other species, with a particular interest in the ever-shifting caribou, whose abundance in a given place one day and total absence the next intrigued him. In time he began to discern patterns that linked their seemingly random movements. He noted, too, the predictability of the sheep, whose pastures, changing with the seasons, largely defined his own rounds. Birds, bears, moose, foxes, and the multitudes of small creatures, including many species of field mice and voles, caught his attention, and their habits were noted as he tracked the sheep. The rutting behavior of caribou and sheep he described. Predation and flight, the antics of animals at play—all these he recorded.

For a man like Sheldon each season was another act in Nature's drama, each valley or ridge a setting, each event a scene. Winter landscapes, appearing to casual observation dim and lifeless, spoke strongly to Sheldon of life, of infinite adaptations by the many creatures that survived and found sustenance there despite deep cold and darkness only faintly relieved by a horizon-hovering sun. And then, of course, came spring: light, renewal, return of migrant birds, flowing waters, greening of plants, and then the short summer's surge to start the new generations.

The Wilderness of Denali—essentially Sheldon's field notes edited by Nelson and Merriam after his death [16]—captures the endless fascination of this naturalist's Shangri La. In short, Sheldon fell in love with this country. The rush to accomplish too much that previous summer was replaced by a deliberate and contemplative energy. During this year he had time for people, and he became fast friends with Joe and Fanny Quigley. He got to know Tom Lloyd and his partners—Karstens' old comrades, the future Sourdough climbers—sharing with them his understanding of the mountain's topography. He met some market hunters, men he understood, but whose work worried him.

As Sheldon roamed the Denali wilderness another purpose—beyond the life history of the sheep—began to take form. He later confided to Madison Grant, fellow Boone and Crockett Club member and historian of the Mount McKinley Park movement, that it was the club's interest in establishing game refuges, particularly in Alaska, ". . . which inspired in him the thought of preserving this area after personally studying the situation in that land." [17]

As long-term chairman of the club's Game Conservation Committee, Sheldon would help lead the club's evolution from the original ideal of a comradeship of riflemen and hunters toward a far-reaching ethic of conservation. This transformation matched the Nation's evolution from frontier to almost old-world conditions. [18] In Alaska, even then the Nation's last frontier, the Boone and Crockett Club, under Sheldon's leadership, would focus its new concerns on the establishment of a park-refuge that would preserve Denali's wildlife.

Except for the nascent idea, the park movement was still in the future when Karstens and Sheldon shared camp together. They did talk about market hunting: its potential impact as the surrounding country developed, and the waste entailed by the hunters feeding their dogs half or more of the meat taken before it could be delivered to the mining camps or Fairbanks.

As they roamed the country the idea of a park-refuge found embodiment in the landscapes occupied by the wandering animals. In a letter written on July 25, 1918, Karstens recalled his work with Sheldon beginning in 1906:

He was continually talking of the beauties of the country and of the variety of the game and wouldn't it make an ideal park and game preserve. . . . He came in the following July hunting for the Biological Survey and stayed a year, during that time . . . we had located the limits of the caribou run. We would talk over the possible boundaries of a park and preserve which we laid out practically the same as the present park boundaries. [19]

With a sorrow he could not describe Sheldon left Denali and Alaska in the summer of 1908, never to return. But the idea of a "Denali National Park" (so named in his journal entry of January 12, 1908) [20] remained fresh in his mind. He envisioned accommodations and facilities for travel that would allow visitors the same enjoyment and inspiration that he had been privileged to experience. The essence of the park would be its heraldic display of wildlife posed against stupendous mountain scenery.

Upon his return to New York, Sheldon broached the park idea to his friends in the Boone and Crockett Club. He was heartened by their enthusiastic response. But all agreed that the time was not ripe for a public campaign. Congressional interests had turned from conservation issues, and the club, Sheldon included, had more urgent business to attend to. For the time being the prospective park's remoteness, paired with the decline in nearby mining activity, would have to suffice for its protection. [21] As Sheldon and his colleagues bided time they refined the park concept.

Then in 1912, began a series of events that would vault the park proposal into the public arena. That year Congress passed Alaska's second organic act, providing for territorial status. To the existing offices of governor and non-voting delegate to Congress, the act added a territorial legislature. This body offered a political focus for working with the people of Alaska on the park proposal. Moreover, during the period of the park movement the delegate to Congress would be Judge James Wickersham, a friend of Sheldon's and an occasional dinner guest at Boone and Crockett Club affairs.

Tacked onto the organic act was a rider creating an Alaska Railroad Commission that would report on "the best and most available routes for railroads in Alaska which would develop the country and its resources." [22] President William Howard Taft appointed as chairman of this commission Alfred Hulse Brooks, another old friend of Sheldon's through their association in the Explorers Club. The commission quickly did its work and in early 1913 recommended two railroads to the Interior: one from Cordova to Fairbanks via the Copper and Tanana rivers, giving access to the Yukon Valley; the other from Seward via the Matanuska coalfield and Susitna River, then over the Alaska Range into the Kuskokwim Valley, opening up Alaska's second largest drainage system. After heated debates over the proposed routes and the socialistic implications of a government-built and-operated railroad, a single compromise route to Fairbanks via the Susitna and Nenana rivers was chosen. This route would tap both the Matanuska and Nenana coal fields. And, through purchase, it would start off with 71 miles of privately built Alaska Northern Railroad track running from Seward to Turnagain Arm of Cook Inlet, and another 39 miles of the Tanana Valley line from Fairbanks.

Fears of socialism subsided in Congress as railroad entrepreneurs testified in favor of a government railroad to open up Alaska's Interior. They maintained that except for short mining-associated railroads, private efforts had failed to overcome Alaska's terrain, climate, and vast unpopulated spaces. A government railroad was essential if the Interior were to be opened to commerce, homesteading, and general progress of the sort that had followed railroad land grants and financial incentives in the Trans-Mississippi West. Finally the Alaska Railroad Act passed Congress and President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law on March 12, 1914. [23]

The Congressional focus on Alaska legislation (organic act, railroad, coal leasing, land grant college); [24] the certainty of increased market hunting to supply railroad construction camps on the east side of the Denali region; and the prospects for gold-mining revival, coalfield development, and town-building along the rail line—all leading to yet more depredations on Denali's game—brought the park proposal to a head.

On September 21, 1915—with railroad construction already underway—the Boone and Crockett Club formally resolved to endorse the proposal for creation of a Mount McKinley National Park in Alaska. (Sheldon would continue to urge the name Denali, but Mount McKinley won out.) Sheldon and Madison Grant comprised a committee to carry the resolution into effect. Sheldon opened the campaign with letters to Delegate Wickersham and his old friend Doctor Nelson of the Biological Survey. [25]

Sheldon brought Wickersham in by seeking his views on the park proposal and how it might be received in Alaska, to which Wickersham promised careful consideration. But the letter to Nelson was a detailed statement of strategy. After noting that the time was now ripe for pushing the proposal and sketching boundaries that would "include a wide area of the best sheep, caribou, and moose country," Sheldon confided to Nelson:

Before doing anything about it, I wish to go to Washington with the plan complete as I wish to project it and win over Wickersham, the delegate from Alaska. He was once a strong friend of mine and I have been careful to say nothing publicly against him [in debates over the proposed Alaska Game Law], always with a view to winning him to this project at the opportune time. After I get him and the Secretary of the Interior and a few influential senators and congressmen, I shall start the campaign by a B. and C. [Boone and Crockett Club] dinner in Washington composed of congressmen and senators and others specially with a view to this plan. I shall try to win over the Alaska people first. You should say nothing about this yet, since I want to make Wickersham feel he is the leading spirit of it etc. etc. . . . After the plan is well underway then my successor on the Game Committee will have a definite object to work for. I believe that the creating of a demand for this in Alaska will be the key to the whole problem and perhaps I can assist in establishing this. . . . It is absolutely necessary that it should not get out in any detail until I see Wickersham and so arrange things that he will get the credit for the idea which the B. and C. Club will stand behind and support.

The railroad which will reach that part of the country in two or three years makes a good reason for the Park, if the game is to be preserved as a reserve for that part of the country which is somewhat far for market hunters of Fairbanks. This letter to you marks the date when the idea is launched. [26]

Sheldon's calculated approach was not frivolous intrigue. During the park proposal's gestation the Boone and Crockett Club and other big game groups had been working with the Biological Survey and Congress to strengthen the Alaska game code. A law of 1908, passed over Alaskan objectives, had set bag limits to reduce the wholesale slaughter of bears and other species, and it had established a system of game wardens, game-guide registration, regulations, and permits to be administered by the territorial governor under the technical guidance of the Biological Survey. This law and the system it begat, including the inevitable "bureaucratic absurdities" (e.g., a late waterfowl season that postdated southerly migrations from northern Alaska), aroused Alaskan ire. The argument that Alaska's game was part of the Nation's public domain immediately polarized national vs. local interests. Those who subsisted on game, those who hunted for the town and camp markets—remote places where beef could not be raised and cost a fortune when imported, and those who routinely killed bears wherever found because they were "savage beasts" had no patience with Eastern Establishment and federal interference. Successive territorial governors and the territorial legislature after 1912 reflected overwhelming Alaskan sentiment when they called for home rule over Alaska's wild creatures. "Arrogant cheechako" (i.e., greenhorn, especially of the Eastern variety) battled "local bar-room bear hunter" over the fate of Alaska's wildlife, in a frame of argumentation little changed to the present day.

The onset of World War I—which among other things caused inflation and diverted shipping from Alaskan waters, further stressing tenuous supply lines—exacerbated the struggle between stateside conservationists and Alaskans. The latter called for a ban on all hunting restrictions so they would not starve or be bankrupted by "the beef monopoly." [27]

The first hints of this wartime game preservation battle—which would become nationwide—registered in Alaska even before the United States entered the war in April 1917. This was partly a result of vastly increased U.S. ship-borne trade with the Allies centered on food and war material.

In this heated atmosphere Sheldon and Doctor Nelson would advocate a middle course toward market hunting that recognized Alaskan difficulties but would yet avert lasting damage to Alaskan wildlife (e.g., game shot legally could be sold). But other conservationists stood firm on the main tenet of game preservation in this country: no commercial hunting. [28]

Thus, from the inception of the park idea to its enactment, the Mount McKinley park refuge proposal had to dodge and weave through a political minefield of strenuous opposition in Alaska. In addition, the conservation community itself would split over compromises on hunting that were the price paid for critical Alaskan support for both realistic hunting controls and a Mount McKinley National Park. The adamant and inflexible William T. Hornaday of the New York Zoo and the Permanent Wildlife Fund would brook no bending of the ban on commercial hunting. Sheldon and Doctor Nelson viewed him as intemperate, a potential derailer of those moderate game-and park-law provisions essential for any controls over Alaska's game. All those who understood the situation in Alaska knew that absolute solutions would fail in the vast territory with its mere handful of game wardens. [29]

In this context of larger affairs—international, national, and territorial—political acumen was essential to the life of the park movement and its successful conclusion. Proponents had to play both ends against the middle with perfect timing. For example, the respected Stephen Capps of the U.S. Geological Survey reported that market hunters were taking 1500 to 2000 Dall sheep from Denali's Toklat and Teklanika basins each year. This disturbing news, published in the National Geographic Magazine in January 1917, helped push the park bill through Congress the very next month.

As there were dangers, there were also opportunities when the Mount McKinley park movement began in 1915. That same year conservation-minded Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane invited his former college classmate Stephen T. Mather to come down to Washington and run the national parks himself if he didn't like the way others were doing it, as Mather had complained in a letter. Indeed, administration of the 13 existing national parks, plus several national monuments and other units, left much to be desired. No system as such existed. Rules varied from park to park. Superintendents and custodians a were a mix of military and civilian personnel. Some of the latter, being local political appointees, made up their own rules as they went along. Loose guidance from successive Secretaries of the Interior meant that nobody was really in charge. The parks were orphans of the federal government. [30] Secretary Lane, reflecting the aggressive executive-branch philosophy of the Wilson administration, wanted to change this.

Mather came to the department from a background of successful business and newspaper experience. He was 47, dynamic, and financially independent—ready to perform public service for the wildlands he loved. As Lane's assistant for National Parks Mather teamed up with Horace M. Albright—a young research assistant who had been studying the condition of the parks for Lane. Their joint objective was to get Congressional sanction for a National Park Service that would manage the parks and monuments as a system. This reform became reality in August 1916 with passage of the National Park Service Act. Mather became Director and Albright Assistant Director of the new bureau. [31]

Into this activist and expansionist camp came Sheldon's proposal for a new national park in Alaska. As it turned out, Mount McKinley would become the first national park admitted to the system after creation of the National Park Service.

|

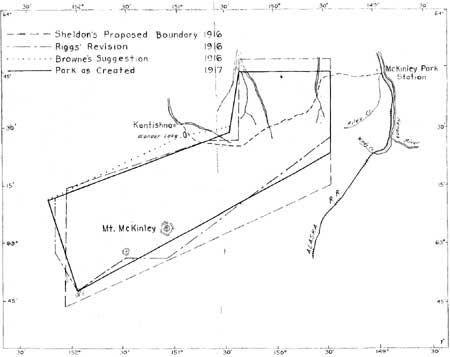

| Proposed boundaries for Mount McKinley National Park, 1916-1917. Kauffmann, Mount McKinley National Park, Map 1. |

Sheldon wrote to Mather on December 15, 1915, using the Boone and Crockett Club's Game Preservation Committee letterhead, which listed such conservation luminaries as Sheldon himself (chairman), Charles H. Townsend, E.W. Nelson, and George Bird Grinnell. Sheldon described his visits to the Denali region, his love of its wilderness and wildlife attributes. He said that on this continent only the Grand Canyon could compare to the "region of the Alaska Range for the grandeur of the scenery and the topographical interest . . . From his first visit, Sheldon related, he had "believed that someday this region must be made a national park." The imminence of railroad construction made this time "peculiarly auspicious" for legislation because the proposed park's "vast reservoir of game" would otherwise be destroyed to supply meat for the construction camps. The park's status as a game reservation would have to be made explicit in any bill. Interests of miners on the fringes of the park would have to be protected. But the boundaries Sheldon had recommended should exclude significant areas of mineralization from the park. It was essential that Delegate Wickersham be assured that his local constituents would be protected. Only then would Wickersham introduce the park bill, giving it Alaska's stamp of approval. The Boone and Crockett Club would stand behind the effort and assist in its passage through Congress. Sheldon then proposed a meeting with Mather to be followed by presentation of the proposal to Secretary Lane. The letter ended with a note of urgency: Postponement of action on Mount McKinley National Park could lead to destruction of its wildlife values, the key reason for designating such a park in the remote Alaska wilderness. [32] This letter defined the substance of the struggle for park legislation and the counterpoint arguments of the opposition. Mather endorsed the proposal without quibble, accepted associate membership in the Boone and Crockett Club, and on January 6, 1916, addressed the club's members in terms of his and Secretary Lane's full support for Sheldon's plan. [33]

The park idea soon captured the imagination of a significant part of the Eastern elite, including government leaders and scientists in the conservation and wildlife preservation fields. It was a simpler time, those early years of the century. The excessive layerings of today's government did not exist. Movers and shakers in business and government interlocked through their schools, career paths, and clubs. Phone calls and hastily scribbled notes sufficed to align key people when a change of course or a tactical diversion was necessary to steer a piece of legislation, as the McKinley park proposal would demonstrate.

Coincidentally, as the park movement got underway, Belmore Browne of the Camp Fire Club of America independently evolved a similar plan for the Denali region's preservation. When he presented his proposal in Washington he was surprised to find the Boone and Crockett Club and his friend Charles Sheldon already in the field. Quickly the two clubs joined forces and brought into the fold the American Game Protective and Propagation Association, whose president, John B. Burnham, would become overall coordinator of the legislative effort.

Alaska delegate Wickersham—always conscious of the needs of his Alaskan constituency—saw the advantages of the park in bringing visitors to Alaska from around the world. He would introduce the park bill in the House in the spring of 1916. Thomas B. Riggs of the Alaska Engineering Commission (and later governor of Alaska) saw the park as an aid to the fledgling Alaska Railroad, whose 400-mile wilderness route from Anchor age to Fairbanks would benefit from tourist traffic. He would, with Sheldon and Browne, draft the park bill, using Sheldon's recommended boundaries. With remarkable speed the teamwork of the three clubs and the inside help of Lane and Mather at Interior propelled the park bill into the hands of receptive legislators and onto the legislative docket. Wickersham's bill in the House, introduced April 16, 1916, was matched by an identical companion bill introduced by Senator Key Pittman of Nevada.

Then momentum slowed as amendments unacceptable to Wickersham and other members of Congress jammed progress. These difficulties would be overcome, finally. But yet another hitch doomed the House bill in 1916. The House Committee on Public Lands, following an informal rule, would report favorably on no more than two national park bills in a single session. Just as the McKinley bill got close, two other park bills were reported, so the House delayed action. Pittman's Senate bill, however, passed unanimously.

When Congress resumed in January 1917 the park-bill proponents were ready. Their work during the Congressional recess resulted in piles of letters and editorials favoring creation of the park. Dr. Stephen Capps' supportive article in the January 1917 National Geographic Magazine also greeted the returning Congressmen. It stressed the urgency of stopping market hunting before Mount McKinley's wildlife was killed off. Several legislators attended the first National Park Conference, staged largely for their benefit, hearing pleas for the Mount McKinley legislation by Sheldon, Browne, and Mather, among others. Earlier committee hearings on the bill had given proponents another forum. The bill passed on February 19. And—in recognition of his park idea and tireless efforts to bring it to fruition—Charles Sheldon was delegated to deliver the act personally to President Wilson, who signed it on February 26, 1917, and gave the pen to Sheldon. [34]

Many years later Horace Albright recalled a footnote to this triumph: Sheldon had moved from Vermont to Washington to shepherd the park bill through. During the climax of the legislative process he had haunted the halls of the Capitol and mobilized his cohorts for the final push. Finally, he took a day off, and that was the day the bill passed. Next day, Albright, acting as Park Service director at the time, saw Sheldon approaching his office, jumped up, grabbed his hand, and congratulated him for leading the creation of this great park. For his part, Sheldon stood aghast. Unaware of the bill's passage he had dropped by simply to check progress. His day off made him miss the vote. "He kicked himself the rest of his life that that was the one day he didn't go up there." [35]

The Mount McKinley National Park Act reserved some 2,200 square miles laid out in a rough parallelogram nearly 100 miles long and averaging 25 miles wide, running from the southwest to the northeast. At its upper end it expanded to the north to include the mountainous sheep and caribou country of the Toklat and Teklanika drainages. The boundaries excluded the Kantishna mining district and the forested moose country to the northwest where many miners wintered and hunted. The park captured the ridgeline of the Alaska Range, which backdropped the bordering piedmont plateau, the great valley of the Denali Fault, and the north-side outer ranges crossed by the north-flowing Toklat and Teklanika rivers.

As Sheldon himself described the park, it was a country

mostly above timberline, and yet with tongues of timber extending up the rivers. Outside of the rough ranges are gently rolling hills, hundreds of little straggling lakes, a region which, when roads are once established there, and conveniences for tourists, you can ride all over it with horses. It is accessible in every part, and the game of the region will be constantly in sight, a thing which is not true of most of the regions of our other national parks. [36]

The price of this idyllic vision had been compromise. Delegate Wickersham had promised to protect his constituents in Alaska, and he did so. In addition to the Kantishna and northerly hunting-ground exclusions (which cut into the extended ranges of Denali wildlife), the law provided that prospectors and miners could locate new mining claims within the park. They could also "take and kill game therein for their actual necessities when short of food," but not for sale or wantonly. [37]

Amendments proposed by some conservationists to give the Interior Secretary greater regulatory control over these mining-related provisions had proved inimical to the bill's passage. Wickersham dug in his heels and was suspected of pushing the House Committee to render favorable reports on two other national park proposals, thus using up its first session quota and killing the McKinley bill in 1916. But the pragmatism of Sheldon, Burnham, and Grinnell, among others, led to withdrawal of such amendments, and the bill proceeded to passage in the second session. These and other maneuvers lend a chess-game intricacy to the trail of correspondence during this period, much of it in the Mount McKinley Correspondence File (1916-24) in the National Archives.

The practical views of the chief sponsors, plus the urgency of protecting Mount McKinley's splendid assemblage of wildlife from the construction and development impacts of the railroad, had pushed the Mount McKinley proposal to enactment. Without that urgency—given plausibility by the repute of the chief sponsors, and by earlier revelations of wanton slaughter during the Alaska game code hearings—it is doubtful that the bill would have gone through. Alaska was a remote wilderness territory except along the coast and the major rivers. What need for a park designation in the mountainous Interior? Certainly the high mountains—girt by sub-ranges, vast gorges, and immense glaciers—needed no protection. So it boiled down to the wildlife, as the Congressional-hearings testimony amply demonstrates. [38]

Visitors would view that wildlife, which, with the mountains, composed that living landscape that had so moved Sheldon and shaped his vision. The utility of a great, unhunted game refuge in Alaska's center lent practicality to a proposal esthetic at its core. Here would be a reservoir of animals, which, upon overflow to surrounding regions, would supply the staunch miners and pioneers at frontier's edge. Thus would development of the country proceed apace, aided by visitors to the park whose locally expended funds would fuel progress, and whose enchantment with the country might lead to their own or others settlement there. [39]

On paper, all of this seemed certain to come about. But having created the park, Congress then rested. Minuscule appropriations proposed by the National Park Service and the Interior Department failed of passage. The war and immediate postwar turmoil had much to do with this. Whatever the causes, the park would suffer from this neglect.

Within a day of two of the President's signing of the park act, Sheldon had dashed off a note to Mr. Grinnell: ". . . I have been working to have included in the Sundry Acct. appropriations bill 10,000.00 for protection of the park and surveying the East North South and West line so that the game areas will be known." [40] But as Sheldon feared, the confusion of the last days of the session sidetracked this minor bit of business. The park would remain vacant of protectors, unmarked on the ground, and prey to poachers for more than 4 years.

During this interval, letters to Sheldon from his Alaska friends reported that poaching in Mount McKinley Park was on the increase. Railroad construction and the towns that sprang from its camps pushed on the park. So did the mining camps rejuvenated by the railroad. The National Park Service, frustrated by failure of its funding requests, arranged with the Governor of Alaska to have his wardens visit the park occasionally, but these rare inspections yielded nothing of protection, only evidence of the need for it.

In a resolution of January 10, 1919, the Boone and Crockett Club respectfully urged that Congress appropriate not less than $10,000 for a ranger force, with proper quarters and equipment, to protect the wild animals of the park, with a final paragraph that chided the Congress for its 2-year delay. [41] Five days later the Camp Fire Club of America issued a similar resolution. [42]

Territorial Governor Thomas Riggs, upon receipt of a copy of the Camp Fire Club resolution, wrote to the Interior Department requesting aid for the park so that its function as a game reservoir for the surrounding country, and its wildlife attraction for tourists, would be protected. Interior's Assistant Secretary John Hallowell responded to Governor Riggs with assurances that the Department had consistently pressed for appropriations for the park. He quoted Park Service Director Mather's memorandum in response to the Governor's plea: ". . . ever since the creation of the park, we have each fall submitted, with our other park estimates, one for Mount McKinley, to the amount of $10,000, the limitation placed in the organic act." Hallowell concluded his letter to Riggs with the hope that the House Appropriations Committee would see the light in the coming year, but warned that the war-debt problem was making many useful projects postponable. [43] Still there was no result.

More than a year later, on November 17, 1920, Sheldon wrote to Grinnell:

. . . to me the worst news is that the game, particularly the sheep, in the McKinley Park are rapidly being killed off by the market hunters. . . [and the new influx of miners to the Kantishna]. Unless all the clubs in N.Y. and Burnham get together and make a drive for an appropriation this winter, there is serious danger to the game, particularly as the railroad will reach there soon. [44]

A month later, in a letter to the House Committee on Appropriations, Sheldon cited all of the above, including fears that renewed mining activity in the Kantishna might cause a full-scale rush that would "add to the slaughter already going on there." He concluded with the information that "plans for a wagon road to this region have been completed." [45]

The conservationists' bombardment and the desperate efforts of Steve Mather and Horace Albright finally jolted Congress to action. An $8,000 appropriation was passed for 1921. The park's pioneer era would soon begin.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

dena/hrs/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 04-Jan-2004