|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION I:

INTRODUCTION TO DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL MONUMENT

A. Summary of Mining Activity

1. Slow Beginnings

The mineral resources of the Death Valley area have been assessed and investigated ever since the days of the California Gold Rush. Extending over a period of at least 120 years, the fascinating and often complex mining history of the region has unfortunately been overshadowed by the much shorter but more romantic adventures experienced by the Bennett-Arcane party and other groups of the '49ers who attempted to cross the valley floor on their way west to the goldfields. For several years after their harrowing travails this desolate area was regarded as a vast, forbidding tract, and only a few daring souls finally ventured into it again in the 1850s, enticed by rumors of the Lost Breyfogle Mine and the fabulously-rich Gunsight Lead. Many unfortunates, unaware of and unequipped for the hardships involved, perished from the heat, the lack of water, and other excruciatingly painful inflictions perpetrated by the harsh environment. Their persistent endeavors, however, not only resulted in formation of several early mining districts, but also contributed enormously to the growing store of knowledge about the topography and resources of the region that was slowly being acquired through military surveys and personal exploratory forays.

Mining in Inyo County, and especially in Death Valley, was slow in gaining momentum, though by the early to mid-1860s there were reportedly fourteen quartz mills and 130 stamps at various locations in the county. [1] Despite their enthusiastic beginnings, the early mining districts met a notable lack of success in their endeavors to extract and process their ore due to a variety of reasons, including lack of money, primitive and inefficient technological methods, the constant threat of Indian depredations, the scarcity of water and fuel, and especially the absence of nearby transportation facilities, which made it economically impossible to mine any but the highest-grade ores. The silver excitement at Panamint City, lasting from about 1874 to 1877, roused the mining community for awhile from its sluggish state, and was soon followed by the establishment of other mining ventures in such places as Chloride Cliff, Darwin, Lookout, and Lee.

From the 1880s to the early 1900s, however, only sporadic and limited mining operations were attempted in the Death Valley region. None of the camps lasted, again due mainly to the factors mentioned earlier, which still exercised a strong influence over the course of mining in the valley and the surrounding mountain ranges. The still-limited financial means of most miners left them little option--to either strike enough pay dirt immediately to finance future operations, or else shut down. The exciting discoveries of gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota, at Leadville, Colorado, at Tombstone, Arizona, and elsewhere in the West attracted many men away from the region who were already discouraged by their inability to make paying propositions of their remote and inaccessible mines in Death Valley. It was actually the discovery of nonmetallics in the area, initially of borax and later of talc, that ensured the region's industrial future, for in time these commodities far outweighed the more sought-after metallic elements in lasting commercial value.

2. A New Century Brings Renewed Interest in Metallic and Nonmetallic Resources

Not until the early 1900s did conditions become conducive to large-scale hard-rock mining operations, prompted by a renewal of interest in gold and silver. By this time more people had penetrated the desert regions, and responsible authorities were encouraging the immigration by locating and marking water supplies, roads, and trails with signs and designating them on maps. The primary instigator of this move was the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, which had earlier negotiated passage of a law in California calling for the erection and protection of water supply sources in the state's deserts. The U.S. Geological Survey improved on the situation by surveying certain parts of the southwestern deserts and subsequently publishing maps showing existing trails and water supplies. [2]

A variety of metallic minerals were exploited in Death Valley during the 1900s, including gold (Bullfrog Hills, Skidoo area, Ubehebe, Chloride Cliff, Funeral Mts., Black Mts.); antimony (Wildrose Canyon); copper (Greenwater District, Black Mts.); lead, zinc, and silver (Ubehebe, Lemoigne Canyon, Galena Canyon, Wingate Wash); and tungsten (Harrisburg Flats, Trail Canyon). This activity resulted in the formation of several boom towns whose progress paralleled for a while the maturation of Goldfield, Tonopah, and Rhyolite in Nevada. Much of the productivity witnessed in places such as Bullfrog, Skidoo, and the Ubehebe region was directly attributable to lessees. Often large companies working a particular mine were not immediately successful in blocking out large quantities of shipping ore, due either to time or circumstances, and consequently requested that lessees take over and try their luck. More often than not they were remarkably successful, tending to be more careful in their prospecting work and generally more interested in quality than quantity. Striving to find pay ore as quickly as possible, they worked hard, and were one of the prime factors in the successful development of a mine and thus of the surrounding area. The larger Death Valley towns of the first decade of the twentieth century flourished until the financial panic of 1907 hit, causing in most of them an immediate slowdown of work and often total cessation of mining activity. Prosperous large-scale metallic mining in Death Valley ended, for all practical purposes, by about 1915, though Skidoo, for one, managed to hold on for a few more years.

During World War I nitrate prospecting was carried on in the Ibex and Saratoga springs areas, prompted by the nation's need for the product for use in explosives and fertilizers. After World War II, in the 1950s, tungsten prospectors combed the hills near Skidoo and in Trail Canyon, mostly covering areas previously claimed or prospected. This activity was a direct result of new price stability and the absence of tungsten exports from mainland China. [3] Lead and silver deposits in Wingate Wash were also investigated at this time. A major talc industry that had begun during World War I but that had never thrived because of a limited market and the remoteness of the deposits started up again after the Second World War, as did uranium prospecting.

The search for and mining of metallic resources in the monument has generally been sporadic because of its dependence on the fluctuating selling price of a certain commodity, which in many cases has resulted in the development of particular properties over and over again and the reopening of others because the initial owners were ignorant of a mineral that had since become of economic significance. Most nonmetallic mineral deposits, except for the major talc and borate ones still being worked today, have been of only marginal importance, detrimentally influenced to a great degree by their scattered occurrence in isolated geographic locations, the high transportation costs involved in taking them to market, and the always variable law of supply and demand. All mining in the area has been subject to shifts in international. monetary policies and market controls and to stiff competition with foreign vendors.

3. Attempts are Made to Regulate Mining Within the National Monument

Prior to establishment of the national monument, all publicly-owned lands in the area were open to mineral entry under a federal mining law of 1872 that was designed to promote American mineral development in the nineteenth century. Although lands withdrawn by Presidential Proclamation are normally not open to further mineral location, an Act of 13 June 1933 specifically reinstated rights to mineral entry in some parks, subject to regulations regarding their surface use. Existing claims with valid rights could also continue work. By January 1976 active interest was being maintained in about 1,700 unpatented claims (34,000 acres) in Death Valley. [4] On the valid ones the owner held prospecting and mining rights, but not title to the surface.

Before the repeal of mineral entry provisions in certain units of the National Park System by Public Law 94-429 on 28 September 1976, many inflammatory arguments had arisen between those (primarily in the mining profession) holding the extreme view that mining and prospecting should be allowed to continue unrestricted regardless of any harmful effects, and advocates of the diametrically-opposed belief (NPS officials and environmental groups) that lands within a national park or monument should not be exploited for commercial production, especially of minerals. By 1971 approximately 50,000 unpatented mining claims were estimated to have been located within the monument, 30,000 of which had been filed since 1920, during an era when people were desperate for extra sources of income. About 8,000 acres of private inholdings were patented, the majority of which are mining properties. Today five privately-owned companies possess the largest holdings: U.S. Borax and Chemical Corporation; American Borate Corporation; Pfizer, Inc.; Fred Harvey, Inc.; and Trevel, Inc. Until passage of P. L. 94-429 an average of 200 to 300 new claims were being located in the park annually. Under this law those claims not recorded with the Interior Department by 28 September 1977 were declared null and void. [5]

4. Validity Tests and Stricter Land-Use Regulations are Imposed

Although this law successfully prohibited new mineral entries, existing patented and unpatented claims were still a problem to be dealt with. This has necessitated long and costly investigation by NPS officials and scientists into the validity of unpatented claims within several units of the NPS. If a claim is judged valid, the Park Service may exercise either of two options: permit mining to continue, subject to regulation by the Secretary of the Interior in accordance with strict environmental safeguards, or, if mining activity in that particular spot is potentially detrimental either physically or aesthetically, the federal government has authority to purchase the property. If a claim is determined to be invalid by NPS personnel, the government will initiate court action to declare it void. Patented mineral deposits of known economic value in Death Valley are limited to talc and borates, whose large reserves ensure new exploration and development attempts in the near future.

Today, in order to mine Inside a unit of the park system, the owner of an unpatented valid mining claim or even of a patented one must submit a proposed plan of operations to the park superintendent and regional office that complies with the environmental safeguards set by Congress in 1976, which incorporate provisions of the National Environmental Protection Act. Archeological and historical clearance must also be given to the project. Other restrictions are imposed by permits that are necessary for constructing roads or vehicle trails or for many other mining-related activities.

5. Controversial Aspects of Mining in NPS Areas

One of the most recent threats to the integrity of the national parks related to mining exploration was that posed by a National Uranium Resource Evaluation group intending to survey thirty-seven national parks for forty-five minerals and metals under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy. The stated purpose was to identify lands favorable for the exploration of nuclear-energy fuels. The survey had been authorized by Congress in 1974 to determine whether this country had enough uranium to operate nuclear power plants. The proposal greatly alarmed environmentalists, who feared it would lead to wholesale commercial development of natural areas within the park system. Antagonism also arose between park superintendents and survey personnel, the former also of the persuasion that exploration of such resources in a national park is improper and that it is generally impossible to reconcile large mining operations with an area's integrity as a historic, scenic, and natural preserve. The surveyors, on the other hand, generally held the belief that parks should be opened to mining on a limited basis if the presence of a commodity sufficiently valuable to the national welfare is indicated. The potentially voluble argument was ended by NPS Director William J. Whalen's directive prohibiting such surveys within National Park Service areas. [6]

6. Death Valley National Monument Mining Division

Mining operations in the Death Valley region are carefully monitored by an efficiently-manned mining office, headed by Robert T. Mitcham, monument mining engineer. Death Valley is the only Park Service unit requiring such a large, full-time mining office and staff to administer its minerals management program. This office, aided by rangers who keep tabs on mining activity and enforce the regulations and conditions of the special-use permits, attempts to minimize the impact of mineral exploration and development on the monument, to discourage any prospecting activity involving surface disturbance unless it is related to valid mining claims or demonstrated mineral potential, and to determine officially the status of claims being used illegally and/or on which there are dilapidated structures and broken-down equipment. [7] Without the dedicated efforts of this office, working closely with the park superintendent, the Western Regional Office, and mining company officials, the effects of mining on the human, animal, and plant ecology of the area would have been irreparably damaging.

Within the boundaries of Death Valley National Monument today are the remains of mining ventures whose periods of productivity spanned the years from the late 1850s, when Mexicans first reportedly attempted to work silver and gold deposits using only the most primitive of mining techniques, to today's modern talc and borate operations that employ massive machinery and precise scientific methodology to locate and extract the ore. Only traces of the earliest mines and their associated camps can be found, although in several instances valid, historically significant structures remain in the form of mining-related apparatuses or dwelling and milling structures. Unfortunately, more recent activities involving the search for gold and tungsten in the 1930s and 1950s resulted in the abandonment of a tremendous assortment of unsightly junk on many claims within the park. Despite the fact that many metal and wood components have been salvaged over the years either for scrap or use at other claims, there are still plentiful reminders of past occupation in the form of rusty cars, battered appliances, and dilapidated tin shacks.

B. Setting

1. Land of Varied Attractions

Death Valley National Monument lies mostly within the state of California, although the Bullfrog Hills area in its northeast corner extends over into Nevada. The park was created by Presidential Proclamation on 11 February 1933, and after some boundary changes it now encompasses about 3,000 square miles of varied desert and mountain terrain. Its landscape has been shaped by tremendous volcanic forces resulting in faulting and folding of the earth's crust. Subsequent erosion and deposition have resulted in the spectacular badlands formations along Furnace Creek Wash and in the large alluvial fans at the mouths of the many canyons that open onto the valley floor. Evidence still remains of the Ice Age lake that once filled the valley, formed by runoffs from the nearby Sierra Nevada glaciers.

It is a land of strong visual contrasts, none of which were appreciated by the first white men who entered the region. This group of '49ers became lost in Death Valley while seeking a shortcut to the California goldfields, and escaped only after days of severe hardship and deprivation. Today's visitor is able to view the spectacular scenery from well-maintained roads, and comfortable accommodations help make a visit to the area a most enjoyable experience. Driving along the valley floor from the southeast to the north one passes through about 200 square miles of salt flats, beginning in the sticky playa clay around Saratoga Springs and ending in the salt pinnacles, pools, and marshes that make up the salt pan in the middle section of the valley. Here also is Badwater, lowest elevation in the United States and consequently one of the park's main tourist attractions. Further north near Stovepipe Wells Resort are fourteen square miles of picturesque sand dunes, fascinating because of their instability that makes them victim to the ever-shifting vagaries of the wind and light. In the most northern section of the monument is the Ubehebe, an area of volcanic activity characterized by several craters, foremost among them being Ubehebe Crater, 800 feet deep and one-half mile in diameter. Other tourist attractions in this area include the Racetrack Valley, stage for the moving rocks, and Scotty's Castle, a mansion blending Spanish and Italian designs that was built in the Grapevine Mountains by Albert Johnson, a Chicago millionaire, for Death Valley's enigma, Walter Scott.

In contrast to the parched valley floor, the surrounding high mountain ranges harbor forests of juniper, mountain mahogany, and pinyon and other assorted pines, while thirteen species of cactus are found at slightly lower elevations. Animal life in the area covers a broad spectrum, ranging from chuckwallas, lizards, and snakes, to rodents, the more exotic pupfish and tarantulas, and larger mammals such as the coyote, fox, feral burro, and desert bighorn sheep. The extreme heat of the valley forces a nocturnal life-style on the animal population, somewhat restricting the public's view of them.

2. Weather and Temperature

For about six months of the year, in fact, the heat on the valley floor is unbearable, with temperatures in summer normally climbing well above 100 degrees F., resulting in a phenomenally high ground temperature, especially on the salt pan. The mountain air is generally several degrees cooler, however, prompting the early Indian inhabitants to live on the floor of the valley only during the winter, and migrate to the higher spots in the summer. Rarely is rain able to pass over the enclosing mountain ranges, making precipitation almost nonexistent on the salt flats. Average annual rainfall is about 1.7 inches, though in some years rainfall is inordinately heavy, washing out roads and precipitating flash floods. The unfortunate effects are somewhat alleviated by the appearance in spring of numerous patches of glorious wildflowers, contrasting strikingly with the dark volcanic hillsides.

3. Topography

Death Valley itself is a deep north-south trough thousands of feet below the summits of the mountains that border it. The driving distance from the foot of the Last Chance Mountains in the extreme northwest corner of the park to a point near Saratoga Springs in the southeast corner is a little over 130 miles; the width of the valley varies from around five to over fifteen miles. At about its midpoint the valley narrows and its axial direction swings to the northwest-southeast. Also at this point low sedimentary hills begin to intrude on the desert floor, and have been construed by some as dividing the valley into two separate and distinct entities. An early 1890s government report, in fact, referred to the southern section of the park as Death Valley proper and to the northern arm as Lost Valley, a distinction continued by a host of later writers. Today, however, the entire area is considered an integral whole despite its variations in topography.

4. Panamint Range

The Panamint Mountains that parallel Death Valley on the west were thus designated by Dr. Darwin French in 1860, although the significance of the name is not known. Highest point in the range is Telescope Peak, 11,049 feet above sea level, and a prominent landmark that remains snow-capped most of the year. It is particularly impressive in contrast to the flat, arid desert floor immediately in front of it. The northwest quadrant of the park is bordered by the northern extension of the Panamints, the Cottonwood Mountains, which stretch north from Towne Pass. Their northern tip extends into the Ubehebe area, separating Hidden Valley from the main valley floor. Highest peak of this range is Tin Mountain, 8,953 feet in elevation. Bordering on the west side of Racetrack Valley is the extreme southern end of the Last Chance Range.

5. Amargosa Range

Extending down the east boundary of the park is the Amargosa Range, an all-encompassing term that includes three distinct series of mountains: the Grapevines, in the northeast corner, possessing the longest valley frontage end the highest ridges, culminating in Grapevine Peak at 8,738 feet above sea level; the Funeral Mountains, facing the midsection of the valley and located between Boundary Canyon and Furnace Creek Wash; and the Black Mountains, rising steeply from the salt flats in the southern end of the monument and extending south to merge with the Ibex Hills. The Owlshead and Avawatz mountains close off the southern end of the valley.

6. Roads and Trails

Access to Death Valley is possible via a comparatively large number of mountain passes, many of which, due to the valley floor's situation below sea level, possess relatively steep grades. From the west, entrance can be made via Searles Lake and Trona across the Panamint Valley to Ballarat, thence up into the Panamint Range through Wildrose Canyon, along the old road once used by freighters carrying goods from Johannesburg to Skidoo and environs. The route was originally pioneered by burro trains hauling charcoal from the kilns in Wildrose Canyon to the Modoc Mine in the Argus Range. In Wildrose Canyon the road forks, the southern branch proceeding on to the kilns and Thorndike's camp close to the Panamint crest near Telescope Peak, the other going north toward Harrisburg Flats and Emigrant Spring. Old trails lead across the flats to Skidoo and other nearby mines and prospects. The Harrisburg road has been extended on to the crest of the Panamint Range at Aguereberry Point from which a gorgeous panorama of the valley floor unfolds below. North of Emigrant Spring the road exits from Emigrant Canyon out onto Emigrant Wash, in the north-central part of the valley, joining California State Highway 190 just east of Towne Pass. This faster route crosses over the Panamints from Lone Pine, following the tracks of the old Eichbaum toll road, a forty-mile stretch built in the 1920s from the foot of Darwin Wash to Stovepipe Wells in order to promote tourism in the valley. These two routes are handy for traffic bound between Los Angeles and Goldfield or other northeast Nevada points.

In the extreme north part of the valley, entry can be made from the east over a good paved road from Sand Spring through Death Valley Wash. Another good route from the east leaves U.S. Route 95 at Scotty's Junction and winds down Grapevine Canyon past Scotty's Castle. Titus Canyon, a little further south in the Grapevines, is a one-way road from the east branching off of the Beatty-Daylight Pass Road, and is characterized by a sandy and tortuous grade varying in width and steepness throughout its approximately twenty-eight-mile length. Originally built to promote the short-lived boom town of Leadfield, it is often closed due to washing and erosion. It is now used mostly for leisurely sightseeing trips. The next large pass south, Boundary Canyon, is one of the earliest-known entryways, probably having been traversed by one group of the '49ers. Travelers from Beatty or Rhyolite enter here, and then can go either south to Furnace Creek, west to Stovepipe Wells Hotel, or north to Ubehebe. Furnace Creek Wash is the most famous early passage to the valley, as evidenced by its designation as the "Gateway of the '49ers." It provides access northwest from Shoshone or Death Valley Junction and, like Boundary Canyon, is a natural break in the mountains. Travelers can also enter the monument west from Shoshone and Tecopa via Salsberry Pass.

In the southeast corner of the monument several smaller routes unite near the south boundary before entering the valley below Ibex Spring. One comes from Mojave, Randsburg, and Johannesburg via Granite Wells and Owl Holes Wash; one originates in Barstow and Daggett and approaches the valley by way of Garlic Spring, Cave Spring, and Cave Spring Wash; while a third enters from Silver Lake through Riggs Valley. These are old desert roads built from water hole to water hole, and their use varies according to climatic conditions. Another now-unused route entered the southwest corner of the valley via Wingate Pass, rounding the south end of the Panamints. This road, originally used by the borax-carrying twenty-mule teams, is always sandy, sometimes washed, and always tricky to navigate. Only twenty or so miles of the route are now open to travel, the remainder being part of the Naval Weapons Range.

7. Water Holes

Water is always a precious commodity in desert environments, and no less so in Death Valley, which contains an about-average supply of watering places, although slightly more than Panamint Valley, its higher neighbor to the west, and many more than Saline Valley to the northwest, which contains not a single water source. Most of Death Valley's supply, however, is characteristically warm and tainted with minerals. Several important water holes are located along West Side Road, including Gravel Well; Bennetts Well, named for Asa Bennett of the Bennett-Arcane party of '49ers; Shortys Well; and Tule Spring, now thought to have been the last camping spot of the Bennett-Arcane party before their rescue. In the Panamint Range are Wildrose and Emigrant springs, both heavily used by Indians and miners. Further north on the valley floor are Salt Well, located beside the main valley road four miles southwest of old Stovepipe Wells, actually nothing more than a pothole filled with saline water that is used mostly by stock; Stovepipe Wells, originally two holes about five feet deep providing good water for early Indian and miner transients and later for the Rhyolite-Skidoo trade; Sand Spring, north of the monument boundary; Grapevine Springs near Scotty's Ranch; Daylight Spring near Daylight Pass; Hole-in-the-Rock Spring in Boundary Canyon; Furnace Creek; Bradbury Well in the Black Mountains; and Ibex and Saratoga springs further southeast.

Valley watercourses consist of the Amargosa River, an intermittent stream flowing north through the southeast corner of the monument near Saratoga Spring and continuing up to the vicinity of Badwater Basin where it loses itself in the salt flat. Because it never carries much of a flow it often peters out before reaching even this point. Salt Creek, an undrinkable stream, flows south from about the vicinity of Stovepipe Wells thirty miles down the middle of the valley, and is responsible for the often marshy conditions near the salt pools where it terminates in the Middle Basin area. Furnace Creek, given this name by Dr. Darwin French in 1860 supposedly because of the presence of a crude ore reduction furnace in the vicinity, is fed by Funeral Mountain springs, mainly Travertine and Texas. Its plentiful water supply has enabled the Furnace Creek Wash area to become a veritable garden spot and eventually the site of two large resorts.

8. Tourism

In the years since its opening to the public Death Valley National Monument has become one of California's most popular scenic areas. Its rich and varied history involving the Indian, emigrant, and mining communities, is a constant source of interest and amazement to visitors. Their new appreciation of the area's scenic splendor and of its wealth of prehistorical and historical resources linked to its early aboriginal and mining cultures has done much to dispel the vision of Death Valley as a hot, barren wasteland. [8]

C. A Note on Historical and Archeological Resources of Death

Valley

1. Limited Scope of Present Study

The reader who is looking in this study for another rehashing of the adventures and adversities of the '49ers as they groped their way out of Death Valley, or for another summary of the early penetrations into the region by the Dr. Darwin French and Dr. S. G. George expeditions of 1860, the surveying mission of Lt. J. C. Ives in connection with the U.S.-California Boundary Survey of 1861, or for a resume of the accomplishments of the Wheeler Expedition of 1871 or of any of the later government surveys or U.S. Army reconnaissances, or of the biological survey of 1891, will be sorely disappointed. Although carrying the general title of Historic Resource Study, this work focuses totally on a history of Death Valley mining activities, past and present, and has consciously ignored more than a cursory mention of earlier white visitation. Mention of them can be found in varying degrees in almost every book on Death Valley, and Benjamin Levy's background study written for the NPS in 1969 contains detailed information on their various contributions.

2. Archeological Research and Fieldwork

In the realm of archeological resources, the park is estimated to contain approximately 1,400 archeological sites, most of them prehistoric. A few specialized archeological investigations have been undertaken in the past, such as those conducted by William J. Wallace and Edith S. Taylor in the Butte Valley and Wildrose Canyon areas, but most surveys have been accomplished only under threat of some type of imminent surface disturbance. The most recent archeological work has been carried out by personnel of the Western Archeological Center, Tucson, in the form of reconnaissance surveys requested to be made within 117 claim group areas to determine what resources are present, their condition, and the probable effects of renewed mining activity on them. Little historical archeology has been carried out in the monument in past years, but a number of new sites with potential for historical archeologists have been discovered as a result of the archeological center's recent work and of field explorations by historians from the Denver Service Center. Recommendations of the latter as to historical sites warranting further investigation by archeologists are found in this report. These sites could add substantially to our knowledge of mining techniques, communication and access routes, life-styles, and dwellings of this desert environment.

|

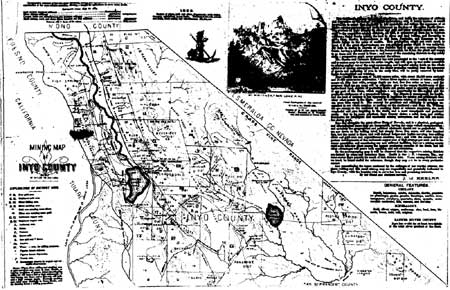

| Illustration 1. "Mining Map of Inyo County," by J. M. Keeler, 1883. Courtesy of Inyo Co. Clerk and Recorder, Independence, Ca. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

deva/hrs/section1.htm

Last Updated: 22-Dec-2003