|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION I:

INVENTORY OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES THE WEST SIDE

E. Furnace Creek

1. Borax Mining in Death Valley

a) Early Production in Region Limited

Borax was first produced commercially in the United States in California at Clear Lake north of San Francisco, from about 1864 to 1868, at which place the industry flourished until the early 1870s when borax began to turn up in large and purer quantities in several of the alkaline marshes of western Nevada (notably Columbus and Teel's) and eastern California. Large deposits were located in the Saline Valley playa northwest of Death Valley as early as 1874, prompting an extensive number of borax land locations up through the 1890s; the discoveries underwent only limited development, however, because of the lack of railroad facilities, the extremely harsh climatic conditions, and the basic fact that they were simply not rich enough to make their exploitation economically viable. In 1874 minor production began in earnest at Searles Lake in San Bernardino County west of the Slate Range where construction and operation of a refinery ultimately turned that valley into one of the most extensively worked and most productive borax areas of the region. Neighboring deposits were subsequently found in marshes near Resting Spring southeast of Death Valley and on the salt pan north of the mouth of Furnace Creek.

b) Harmony and Eagle Borax Works Process "Cottonballs"

The discovery of borax in this latter location was made in 1881 by Aaron and Rose Winters, whose holdings were immediately bought by William T. Coleman and Company for $20,000. He subsequently formed the Greenland Salt and Borax Mining Company (later the Harmony Borax Mining Company), which in 1882 began operating his Harmony Borax Works, a small settlement of adobe and stone buildings plus a refinery. The homestead later known as Greenland Ranch immediately to the south was intended as the supply point for his men and stock. The Amargosa Borax Works in the vicinity of Resting Spring and also a Coleman enterprise was run during the summer months when the extreme heat adversely affected the refining process in the valley. A small-scale borax operation--the Eagle Borax Works--had been begun by a Frenchman, Isadore Daunet, in 1881, and was located further south in the valley near Bennetts Well. It lasted only until 1884 when the inefficiency of its operation combined with personal setbacks resulted in Daunet's suicide. It is frankly amazing that any of these works experienced half the success they did, for their distance from main transportation systems and the daily hardships involved in working under uncomfortable desert conditions were severe obstacles to their economic success.

c) Discovery of Colemanite Revolutionizes Industry

The type of borate being exploited on the salt flats of Death Valley was ulexite, in the form of "cottonballs" that were scraped off the salt pan and then refined by evaporation and crystallization. It was initially believed that this was the only form of naturally occurring borax that was commercially profitable. Continuing exploration in the area by Coleman Company prospectors and others soon confirmed that the playa borates that were presently being worked were actually a secondary deposit resulting from the leaching of beds of borate lime. The primary deposit, a richer form of borate later named in honor of W.T. Coleman, occurred in beds and veins similar to quartz-mining operations. In 1883 three men--Philander Lee, Harry Spiller, and Billy Yount--stumbled upon a large mountain of such ore south of Furnace Creek Wash in the foothills of the Black Mountains. Selling 'Mount Blanco (Monte Blanco)" to Coleman, reportedly for $4,000, they left, having made their fortune off the borax industry. Within a year an even larger deposit east of the Greenwater Range and about seven miles southwest of Death Valley Junction was also found. It was beginning to appear that this was the southernmost lode in a rich colemanite belt stretching northwest to southeast along Furnace Creek Wash from here to the area of present-day Furnace Creek Ranch. Coleman also bought this property, naming it the Lila C.

These discoveries that were soon to revolutionize the borax industry in the United States seemed destined for the moment to lie untouched, for several basic reasons: first, these larger and more concentrated deposits required underground mining methods; second, more sophisticated techniques were necessary for their refinement as they were not readily soluble in hot water; third, no transportation lines extended into this undeveloped area, fourth, no nearby supply center existed; fifth, this badlands region was so scorchingly hot in summer that it precluded mining activity during that season; and last and perhaps most important, Coleman's desert refineries were doing so well that he seemed justified in continuing their operations for a while yet.

d) Pacific Coast Borax Company Turns Attention to Calico Mountain Deposits

These extensive and pure deposits would probably have remained undeveloped if not for the discovery in 1883 of more colemanite ledges in the Calico Mountains twelve miles northeast of the railroad at Daggett in San Bernardino County. Because of their proximity to the railroad these deposits posed a serious threat to Coleman's Death Valley business. Immediately buying up the most important lodes, he decided to look to the future and initiated research at his Alameda, California, refinery in order to determine a profitable method of refining this material. Meanwhile, his Harmony and Amargosa works continued production.

With the dissolution of Coleman's financial empire in 1890, Francis Marion ("Borax") Smith took possession of his holdings at Borate, in the Death and Amargosa valleys, and his Alameda refinery, and consolidated these and other miscellaneous properties into the Pacific Coast Borax Company. In addition he took over the colemanite deposits in the Furnace Creek Wash area. Declining borax prices due to borax imports from Italy and a consequent glut of the product on the market prompted Smith to close down his Death Valley holdings and concentrate on operations at Borate, where richer ore could be refined by less expensive processes. These became the first major underground borate workings in the United States, and during the years 1890 to 1907 Borate became the chief producer of borax and boracic acid in the country. In time, however, the workings had been carried to such a depth that the cost of their further development was prohibitive, causing Smith's attention to turn once more to his Death Valley reserves.

e) Borax Mining Returns to Death Valley and the Lila C

Hindering development of the Lila C Mine was its isolation, but fortunately profits from the Calico operation were sufficient to subsidize construction of the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad, projected to stretch from Ludlow on the Santa Fe line to Death Valley Junction and on to Goldfield, Nevada. Work at the mine started even before the railroad was finished, the initial ore recovered being transported to market via twenty-mule teams, once more pressed into service. The T & T Railroad, begun in May 1905, reached Death Valley Junction by 1907, and a seven-mile-long spur was immediately laid reaching to the Lila C camp of Ryan station. Borate was abandoned and all its equipment moved to the new area where a calcining plant was also installed. The Pacific Coast Borax Company had not forgotten its holdings further west near Death Valley, however, as evidenced by a newspaper report in 1909 that due to the low price of borax the Lila C might have to be abandoned in favor of the more cheaply-mined deposits of Mount Blanco that existed in inexhaustible quantities, such a move being possible with construction of a narrow-gauge from Ryan to the deposits. [1] As the ore at the Lila C began to play out about 1914, plans were already underway to shift operations to reserves further west on the edge of Death Valley. Company engineers had determined that the large deposits here would keep the company going for years, while more was always available on the Monte Blanco and Corkscrew claims.

|

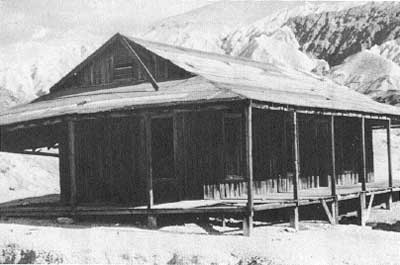

| Illustration 279. Ruins of buildings, and waste dumps, at Lila C Mine, 1943. Photo by Alberts, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

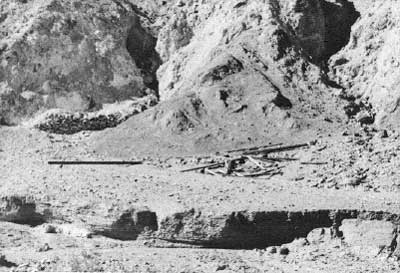

f) The Death Valley Railroad Shifts Activity to (New) Ryan

A new railroad was needed in order to open up these deposits, and this resulted in construction of the Death Valley narrow gauge operating from Death Valley Junction to the newly-opened mines. In January 1915 the Lila C was closed, though not completely abandoned, and American borax activity shifted to the new town of Devair, almost immediately renamed (New) Ryan, on the western edge of the Greenwater Range overlooking Death Valley. A new calcining plant was built at Death Valley Junction to handle the lower-grade ores coming from the Played Out and Biddy McCarty mines. According to the original Death Valley Railroad survey, (New) Ryan was to be only the temporary terminus for a °line eventually extending down Furnace Creek Wash to the Corkscrew Canyon and Monte Blanco deposits as they were needed. This projected extension never materialized, however, because the Ryan mines--the Played Out, Upper and Lower Biddy, Grand View, Lizzie V. Oakley, and Widow--proved even more productive as development increased until 1928 when a deposit of easily-accessible rasorite, more economical to mine due to its proximity to the company's new processing plant, was discovered near Kramer (later Boron), California, again precipitating a shift in mining operations. When the Death Valley Junction concentrating plant shut down in 1928, a significant era in borax production and processing in the Death Valley region came to an end. From then until 1956 borate mining all but ceased, with mines being kept on a standby basis and furnishing only small tonnages to fill special orders. This lull continued until Tenneco, Inc., started open-pit operations at the Boraxo Mine near Ryan in 1971, and subsequent activity seems to suggest that borax mining will again become a significant part of the region's industrial future. [2]

|

| Illustration 280. Mining camp of Ryan, 1964. Photo by Bill Dengler, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

2. Furnace Creek Wash

a) History

(1) Early Mining Districts

The claims staked in the vicinity of Furnace Creek Wash in the early 1880s became part of either one of two mining districts. On 3 November 1882 the Monte Blanco Borax and Salt Mining District was established with boundaries

Commencing at the south east corner of Death Valley Borax and Salt Mining District, 2 miles east of the mouth of Furnace Creek, thence running north 15 miles, thence east 15 miles, then south 30 miles, thence west 15 miles and then north 15 miles to point of beginning. [3]

This district included most of the borax sites being worked or held in reserve today, such as the DeBely, Low Grade, Little Shot, Dot, Hard Scramble, and Monte Blanco borax deposits. The Death Valley Borax and Salt Mining District, formally established on 25 May 1883, had boundaries

commencing two miles East of the mouth of Furnace Creek wash and running North parallel with the Mountains fifteen miles, Thence West across Death Valley fifteen Miles Thence South along Panamint Mts. fifteen miles Thence East to place of beginning. [4]

|

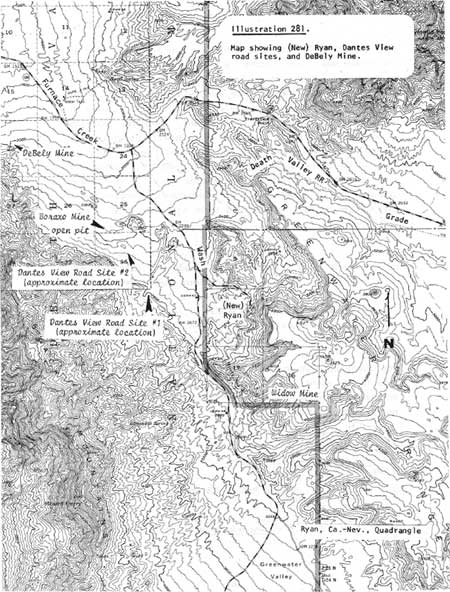

| Illustration 281. Map showing (New) Ryan, Dantes View road sites, and DeBely Mine. |

(2) Development of Area by Pacific Coast Borax Company

During all the years that the colemanite deposits south of Furnace Creek Wash had been held in abeyance by the Pacific Coast Borax Company, they had not been totally neglected. The company had, in fact, been very careful to establish legal title to the many claims that had been located for them in the area by various prospectors (many subsidized by the Pacific Coast Borax people), and also diligent in performing the necessary $100 worth of improvements necessary each year to maintain ownership. The original discoveries had been located in 1883 and patented in 1887 as placer claims, but it was later perceived by the extent and depth of the ore that these were actually lode deposits, making the basis for the original patents somewhat shaky. This obstacle was overcome by simply incorporating the earlier strikes within the boundaries of newer lode claims. Encouraging prospecting in the area and keeping track of resulting locations, carrying out the necessary surveys, and patenting location rights according to government regulations, while also performing annual assessment work, were time-consuming and often legally-complicated tasks, but by the 1900s when it was thought that these resources might be needed to bolster the failing supplies of the Lila C, the company had successfully obtained indisputable mining rights throughout the Monte Blanco and Corkscrew Canyon areas.

In the 1880s the company's annual assessment work, performed until federal courts confirmed their patents and made protective work unnecessary, was carried out by men either from Harmony Borax Works or the Monte Blanco camp. When borax activity moved to the Calico Mountains around 1890, groups of men left there by wagon each winter to tackle this duty. In the early 1900s men from the Lila C and then from Ryan set up temporary camps on the various claim groups and performed the work. When around 1916 the ever-present threat of claim jumping materialized and some disgruntled employees spurred on by competitors tried to take over some company claims in the area, it took the U.S. Supreme Court to confirm the original ownership. To prevent further encroachment the company proceeded to surround their more valuable Mount Blanco claims with fences of telephone wire string to °wood posts. Annual work was thereafter performed more conscientiously and careful records kept of the improvements made. [5]

Although only very limited development work was carried out on the slopes of Mount Blanco, the area's resources were fully recognized and considered ripe for development if ever needed. When, for instance, a closure of the Lila C was being considered around 1909 or 1910 because of the low price of borax and the expense of recovering it from here, work in the Furnace Creek Wash area increased in preparation for a possible shift of operations. [6]

In the early 1920s another colemanite deposit of exceptional purity was located about 1-1/2 miles from the Death Valley Railroad and supposedly adjoining Pacific Coast Borax Company property. The "discoverers"--W. Scott Russell, C.A. Barlow, and a W.H. Hill--formed the Death Valley Borax Company, moved gasoline hoists and other equipment onto the site, erected a camp, and determined to work the properties "declared by geologists to be the most remarkable and among the richest deposits on record." [7] These claims were filed for patent the next year as the Boraxo Nos. 1 and 2 lodes. A sticky legal question arose due to the fact that this property had earlier been located as the Clara lode Claim by the Pacific Coast Borax Company, and a patent applied for that, unknown to the company, had been rejected on rather nebulous grounds. The company, therefore, assuming ownership, ceased annual assessment work, unwittingly opening the way for later relocation of the site. Ensuing litigation found in favor of the usurpers, forcing the Pacific Coast Borax Company to later buy it back. It ultimately became known as the Boraxo Deposit, and, as stated earlier, its exploitation by Tenneco, Inc., starting around 1970 has renewed borax operations in the Death Valley region. [8]

In 1924 W.F. Foshag of the U.S. National Museum wrote a piece on the mineral deposits of Furnace Creek Wash, noting that the mines of the area were found in either of two districts: the Ryan District, composed of the Biddy Mccarthy (McCarty), Widow, Lizzie V. Oakley, Lila C and Played-Out deposits, and the Mount Blanco District, which was not being mined at that time but had been opened earlier by several exploratory tunnels. This latter area, he said, could be reached from Ryan "by continuing down the Wash past The tanks and taking the only road to the south leading into the clay hills flanking the Black Mountains on the north. The road leads directly to the deposits but the last mile must be made on foot." [9]

In 1956 the Pacific Coast Borax Company was reorganized into the U.S. Borax and Chemical Corporation, which still retains the early mining properties of the former smaller organization in the Death Valley region, including those in the Furnace Creek Wash area extending from the monument boundary west of Ryan northwest to Monte Blanco and then on to Gower Gulch. In this latter canyon quite limited exploratory and assessment work has been done through the years, as evidenced by the presence of only short adits and shallow shafts. The Corkscrew Mine at the head of Corkscrew Canyon has been developed by two adits, but its ore body is considered about exhausted. From 1953 to 1955 colemanite recovered here went into air-dispersed fire retardants for use against forest fires. Utilization of such a retardant, and consequently any further development of the mine, was doomed in the early 1960s by the U.S. Forest Service's determination that boron-based retardants caused soil sterility and were in addition less effective than other products. The DeBely Mine also operated in the mid-1950s to supply borates for this purpose. [10]

b) Present Status

Field work concerned with the Furnace Creek Wash historical sites was conducted in several areas which will be covered here individually, beginning with two sites west of the Dantes View road.

(1) Dantes View Road Sites #1 and #2

At the junction of the Ryan and Dantes View roads a gravel access branches off to the southwest, currently used in connection with mining operations on the Sigma-White Monster ore body. Off this main road tracks lead slightly further west and southwest toward two or three adits dug into the foothills. There is slight evidence of possible habitation sites (ground depressions, wood refuse) but no structural ruins are extant. Site #2 is north of this area and appears to be a borax site contemporaneous with those examined further west in the vicinity of Monte Blanco. At least it manifests the same type of stone walls and mounds. Metal refuse, mainly tin cans, lies all around. The only mine development consists of two adits. This site overlooks the Boraxo open-pit mine on the north side of the ridge.

|

| Illustration 282. Adit at Dantes View road site #1. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 283. Adits and stone wall at Dantes View road site #2. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 284. Close-up of one side of stone wall at Dantes View road site #2. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

(2) DeBely Mine

This open-pit site is reached via a faint road branching to the southeast off the Corkscrew Mine road. Most of the activity here has been limited to the south side of the ridge where surface scraping is evident. Some underground activity has resulted in adits on both sides of the ridge and a couple of vertical shafts.

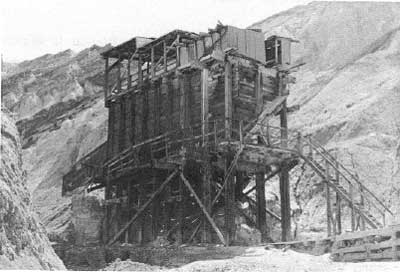

(3) Corkscrew (Screw) Mine

The entrance to this site is through a locked gate east on Route 190 about 1-1/4 miles beyond the exit road from Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon. Mine workings found here alongside a wash consisted of several adits, a huge wooden four-chute ore bin, and an adjacent platform loading area. Activity here was all underground.

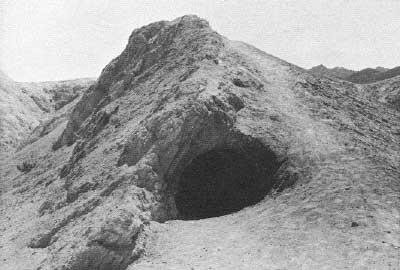

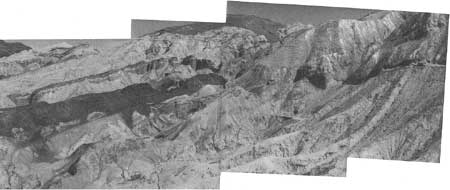

(4) Monte Blanco

This district is about one-half mile south of Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon Road and extends about three-quarters of a mile east-west. Extensive prospecting activity has taken place throughout the hillsides along Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon road and between it and the Monte Blanco area. Resources found near Monte Blanco include a collapsed dugout, used either for habitation or storage, fashioned from sandbags. Some timbering was exposed and bits of pinyon pine bark were found imbedded in the sand. Stretching over every ridge are fence posts, some with wire still attached, and several bails of wire were also found lying on the ground. These are boundary lines remaining from the early 1900s when the Pacific Coast Borax Company endeavored to discourage claim-jumping by enclosing their richest claims.

|

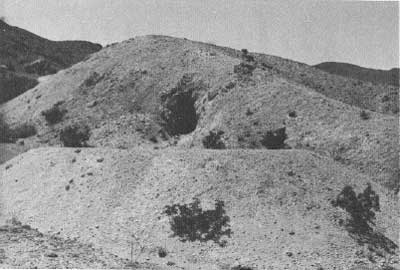

| Illustration 285. DeBely Mine, view to northwest. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 286. Ore bin at Corkscrew Mine. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

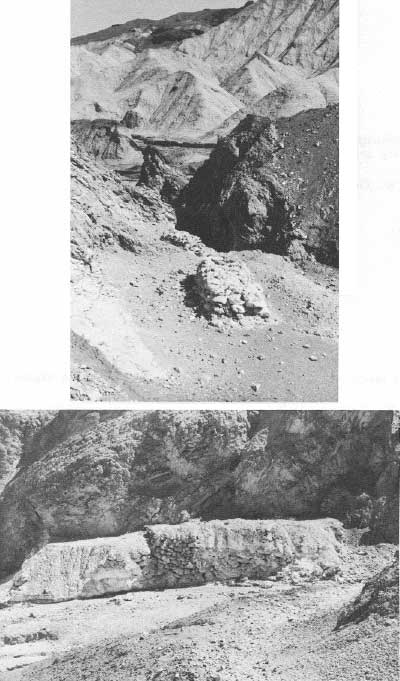

The pyramidal-shaped light-colored formation referred to as Monte Blanco shows signs of thorough exploration. On its north face are five stone foundation walls, probably loading or machinery platforms. One wooden chute remains intact, though there is evidence nearby of others. A wagon road circling in front of the mountain makes a complete loop back to the access road, which eventually intersects with another mining road further east and leads back down toward the Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon Road.

Southeast of Monte Blanco is another lofty ridge on which several adits have been worked and on which more stone walls are periodically visible. The long road leading up toward this area has been shored up at one point by means of a low stone wall that carries it across a wash. Many signs of human habitation of the area (leather fragments, tool parts, canvas broken glass, tin cans, etc.) have collected here in the dry streambed. From a vantage point further up this trail, views are afforded over the ridges at other small mining operations and remnants of tram rails leading from adits. The road finally ends after a steep climb at an adit and waste dump site. Alongside the road skirting the edge of the hill here are two large stone mounds, similar to those at the Dantes View road site #2. The first is fifteen feet long, five feet high, six feet wide, and fairly level on top. The second triangular-shaped mound east of this is a mass of piled rocks with sides measuring fifteen to eighteen feet long. Narrow passageways have been left between the rock piles and the hillsides.

|

| Illustration 287. Adit typical of those along Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon Road. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 288. Ruins of sandbag dugout in small wash near Monte Blanco mining area. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

|

Illustration 289. "No ledge or series of

ledges anywhere in the world contains the immense amount of borate

quartz shown on the surface of this mountain of colemanite. It is a body

of ore measuring 100 feet in width and 5000 in length . . . . It is a

borax quarry, whose limitation cannot be roughly conjectured, but it

must exceed by thousands of tons any known borate deposit." Quote from Goldfield News photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 290. Stone loading platform and wooden chute on face of Monte Blanco. Note other stone walls at left of picture. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

Descending from this ridge, the road eventually joins with the Monte Blanco road and together they head back toward Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon. Immediately north of the intersection of these last two roads is the site of the office/bunkhouse/ore-checking station serving the Monte Blanco miners in the 1880s. Although the original wooden structure was moved to Furnace Creek Ranch and remodeled on the interior in the 1950s, the dugout cellar remains. Much debris from the occupation period is strewn on the ground. Northeast of the cellar is a tent site distinguished by tent weights forming an irregular stone alignment. Across Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon Road is another such tent site. Dumps abound in the vicinity.

(5) Gower Gulch

The Gower Gulch mining area is reached either by trail south from Golden Canyon or by following the old 1-1/2-mile-long wagon/auto road from Zabriskie Point that was built in the 1880s by the Pacific Coast Borax Company to facilitate annual assessment work on the ten claims they held in the gulch. The road led to a two-tent camp established as headquarters for men working in the area. [11]

Approximately one-half mile southwest of Zabriskie Point and down in the gulch is a building site on the south side of the dry streambed. Timber remnants are found here in association with a sturdy rock wall, four to five feet high and relatively clear on top, structures similar to which were found at all borax sites in the Furnace Creek Wash area. Also nearby, along the side of another gully are two smaller isolated stone mounds, one two feet high, two feet wide, and seven feet long, the other three feet wide, two feet high, and ten feet long. Short exploratory tunnels have been dug into the ridges here.

|

| Illustration 291. Wagon road and mining area on hillsides east of Monte Blanco. View toward southeast. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 292. Close-up view of two stone mounds found at end of wagon road in above picture. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

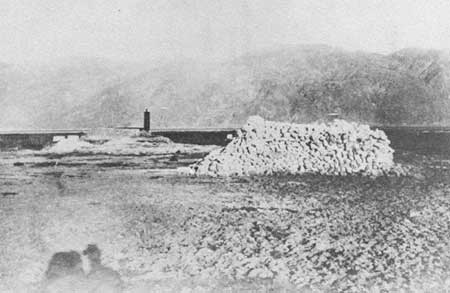

| Illustration 293. View of Eagle Borax Works, photographer and date unknown. Note stone mound (shelter ruin?) similar to those found in Monte Blanco area. Photo courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

| Illustration 294. Monte Blanco assay office on site in Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon. Note cellar entrance on right side of building. |

|

| Illustration 295. Cellar of above structure. Entrance is at top of picture. |

|

| Illustration 296. Tent site across Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon Road from cellar site. Note dump in foreground. Photos by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

Continuing west down the road, which follows the gulch streambed, numerous adits can be seen to the north and south up various gullies and washes. Another large foundation, built of crumbly clay "bricks' and about seven feet wide, showed up at another site south of the watercourse near an adit. About 1-1/2 miles down the gulch is a large group of adits (Six plus) and more stone walls. A long switchback trail extends up over the ridge to the northwest, shored up at points along the hillside. From here on to the mouth of the canyon the gulch narrows considerably, eventually ending in a high dry waterfall, so that this area would be the last place from which entrance or exit could be easily made to these claims. This is the point at which Harry Cower implies a temporary campsite was established for assessment work in the area.

c) Evaluation and Recommendations

(1) Importance of Borax in Death Valley Mining History

The Furnace Creek Wash sites, although subjected to exploratory and assessment work, have not sustained extensive underground mining development. Since 1883 the ore beds here have been regarded as reserve deposits that would be developed if the more accessible and thus more easily mined deposits owned by the Pacific Coast Borax Company in the Calico Mountains and later at the Lila C or Ryan became depleted.

|

| Illustration 297. Wagon road leading from Zabriskie Point into Gower Gulch. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 298. Building site located at spot where wagon road reaches bottom of Gower Gulch. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 299. Two types of stone structures found in Gower Gulch. Photos by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 300. Area of borax mining activity at west end of Gower Gulch. At least five adits are visible. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 301. Switchback trail leading off to northwest from site in picture above. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

Although the possibility once arose that these deposits would be opened up in connection with mining activity at Ryan in the 1900s, the discovery of, and subsequent preoccupation with, the rasorite deposit near Kramer, California, effectively halted further extension into this area. It has only been since the early 1970s that borate mining on a large scale has returned to Death Valley. As borax deposits east of Furnace Creek Wash near exhaustion (the Boraxo ore body is now almost depleted), the mineral belt extending from Ryan northwest along Furnace Creek Wash to the Death Valley floor takes on renewed importance as a still untapped and potentially valuable source of colemanite and the possible site of continuing borax operations.

Certainly the evolution of borax mining--from the establishment of the relatively short-lived Eagle and Harmony Borax Works through the productive years of Borate, the Lila C, and Ryan, up to present-day sophisticated mining operations at the Boraxo and Sigma open pits--is an essential though complex component of the monument's history. The romantic legends that arose around the long, dusty treks of the early borax teams, and later the impressive production records of the region's colemanite properties, drew public attention to the Death Valley area. Construction of the railroad to Ryan facilitated establishment of a large-scale and self-sufficient settlement there, and with the resultant influx of miners and, later, visitors to the town, further development of the valley as a scenic recreation area was inevitable.

The badlands country south of Furnace Creek Wash is closely connected to borax development both on the valley floor and outside the monument at Borate, the Lila C, and Ryan. It is the largest undeveloped borax area within the monument and potentially extremely valuable to the borax industry. Complicating the issue is that it also contains several cultural resources important to the area's mining story and that are not found elsewhere in the area. As stated earlier, it was the discovery of colemanite here that contributed to the demise of the cottonball gathering and evaporation and crystallization techniques carried out at Harmony Borax Works. The evidence of underground work here and the varied types of mining-related resources found during the survey provide a marked contrast to the technological processes and living styles connected with the salt pan operations. Incorporating the history of this area into monument programs would be a logical extension of the interpretive effort centering around borax mining in Death Valley and environs.

(2) Variety of Cultural Resources Present

Several significant cultural resources found in this area have thus far not been found elsewhere in the monument to the writer's knowledge. Three types of tent sites may be represented: in some instances the tents were placed directly on the ground and secured by wires attached to stone weights. Examples of these are found near the Monte Blanco assay office site along Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon Road marked by rock alignments. In Gower Gulch tents might have been erected on some of the high stone platforms constructed along the sides of washes. In one instance, at least, they appear to have been erected on low stone foundations and reinforced with wood around the sides. The sandbag dugout found west of Monte Blanco, although it might have only been used for storage, might also have been a shelter against the intense heat and blinding sandstorms before it caved in. The subterranean excavation alongside Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon Road is all that remains on-site of the oldest extant building in Death Valley. This area, with its accompanying tent sites, privy pit, and refuse dumps, has potential significance for historical archeology.

The large stone mounds and the many rock walls and platforms found in the Furnace Creek Wash area require further study to determine their exact purpose. No documentary data alluding to such structures in connection with borax operations has been found; it is possible that historical archeologists could discover some clue as to their function. The large wooden ore bin at the Corkscrew Mine is not significant structurally, resembling bins at many of the quartz-mining operations in the monument, and is of fairly modern vintage. It is, however, the only ore bin in the monument connected with borate mining of the 1950s.

Considering its role in the development of the borax mining industry in California, and the varied cultural remains from the 1880s through the 1950s in evidence along Furnace Creek Wash, this area of Death Valley National Monument is particularly significant. Because some of these sites were not covered during the 1977 archeological survey, it is recommended that an archeologist from the Western Archeological Center inspect the area from Corkscrew Canyon northwest to Gower Gulch and evaluate the significant historical and archeological resources there.

(3) National Register Nominations

The Monte Blanco mining area and the assay office site that was contemporary with it possess National Register eligibility for several reasons: Monte Blanco was the location of the original colemanite discovery in Death Valley in the early 1880s; an interesting dugout variation and large stone platforms and mounds not found elsewhere in the monument to date are found in the vicinity of. Monte Blanco; the cellar site, in addition to being the original location of the oldest extant building in, Death Valley, contains early tent sites in association and has potential for further discoveries by historical archeologists. The Gower Gulch area should be included in such a historic district because the sites here are a continuation and expansion of Pacific Coast Borax Company activities at Monte Blanco.

According to John Craib's 1977 archeological survey of Death Valley mining claims, some of the prehistoric archeological sites found in the Wash area have been determined to be of regional significance, and nomination forms are being prepared by the Western Archeological Center nominating the Furnace Creek Wash unit as part of a larger archeological district.

Furnace Creek Wash (California State Route 190) has added National Register eligibility as the "Gateway of the '49ers," the route followed into Death Valley by early gold-seekers searching for a shortcut to the California goldfields.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

deva/hrs/section3e.htm

Last Updated: 22-Dec-2003