|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION III:

INVENTORY OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES THE WEST SIDE

D. The Valley Floor

1. Presenting Death Valley to the World

a) Resorts Open in the 1920s

Death Valley, land of terrible thirst, whose strange beauty and unique geology long have been associated with romance and mystery--and strange tales of heroism and lingering death--is about to lose its distinction as one of the few remaining regions of the globe known only to the adventuring trail breaker, the hardy prospector and the perspiring borax worker.

Soon the eye of the ubiquitous tourist will view with unconcern its legendary terrors and gaze in perfect comfort and safety upon its grim wonders. Civilization again extends its frontier--and the goodly company of adventurers lose one more of the rapidly vanishing 'far places" of the earth. [1]

|

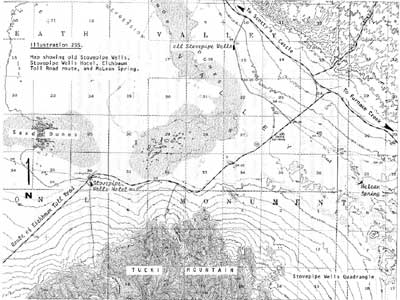

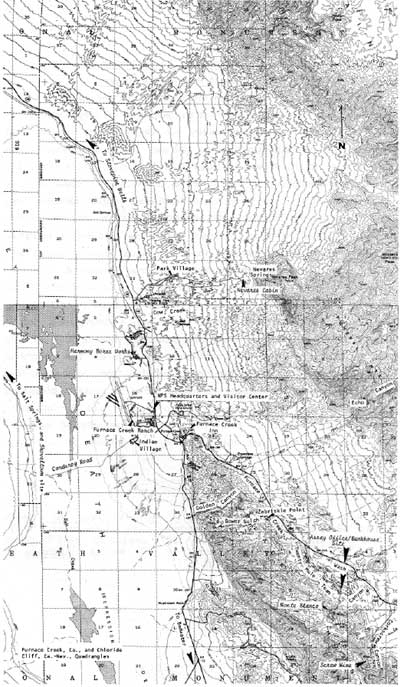

| Illustration 255. Map showing old Stovepipe Wells, Stovepipe Wells Hotel, Eichbaum Toll Road route, and McLean Spring. |

Not until the 1920s did Death Valley's general isolation from the public end and its spectacular scenic and historical resources open up not only to the neighboring populace but eventually to people across the nation and around the world. H.W. Eichbaum accelerated this chain of events by construction of his Stovepipe Wells resort in 1926 in the upper part of Death Valley--the first tourist accommodations in the area. Its northerly location and the fact that it was most easily accessible over the Panamints from the west meant that it attracted people primarily from southern California and the Owens Valley area. The road leading from that hotel south toward Furnace Creek Ranch was, however, a fair desert road, and the opening of Furnace Creek Inn in 1927, offering a whole new segment of the valley to public view, was an added incentive to journey in that direction.

This later hotel was operated by the Pacific Coast Borax Company, which after the cessation of mining activity at Ryan became interested in promoting tourist travel to Death Valley in order to continue operating and making profits off its Death Valley Railroad and its facilities at Ryan and Death Valley Junction. Important strides were made in encouraging travel to the area when the company's project gained the support of the Santa Fe and Union Pacific transcontinental railroads, whose promotional campaigns for package tours did much toward introducing people to this part of California. The chance to be transported in relative luxury on the railroad all the way from Los Angeles, and then to be motor bussed to nearby scenic wonders, meant a comfortable and relatively easy trip for many.

The blessings and approval given to the promotion of tourism here that was offered by various National Park Service officials such as Stephen T Mather, director, certainly were not detrimental to the success of the undertaking. Indeed, Mather was an active consultant with the railroad men and others concerned with the planning phases of the Furnace Creek Inn operation.

Usually it required only one exposure to the valley's awe-inspiring vistas and strange geological formations, and perhaps one day of basking in the temperate climate (further warmed by the knowledge that one's friends elsewhere were suffering winter's hardships), to convince people that here was truly another magnificent winter playground. The chance to view Mt. Whitney, highest point on the continent, and at the same time marvel at its lowest elevation, Badwater, on the floor of Death Valley, was an opportunity not to be missed.

According to Harry Gower, an engineer for the borax people for almost fifty years, this venture into the tourist business was not an easy one for the company or its employees:

Looking back, however, at the adversities of past years, no one can now imagine why we were so anxious to get into the hotel business in Death Valley in 1927. Maybe it looked like a good idea then but certainly in 30 years no great profits from it have plied up in the Company coffers. The principal headaches and drawbacks were the short winter season and the consequent bother and expense of opening up in the Fall, recruiting a staff and then closing down again before the next period of hot weather. Other problems could be listed, such as generation and failures of electric power, production of water, operation of the laundry and the ruinous effect on our equipment of the extremes of the weather, dust, flash floods, etc. [2]

b) Tourism Increases When Area Becomes National Monument

Increased travel was insured when the area was turned over to the federal government as a national monument in 1933, for federal guardianship of its vast acreage meant a corresponding improvement in its roads and facilities. The region's attraction was unique in that it was most endurable and hospitable during the winter when other national parks were blocked by ice and snow. Thus it was in a position to absorb much of the tourist trade crowding into California's sunnier climes. Phenomenal progress was soon made in constructing and either hard surfacing or oiling new highways within the monument, and in opening up new trails and water holes to enable ever-expanding exploration of the valley's resources. Eventually an airport was needed, campgrounds were constructed, and housing for government employees was added. This rapid development resulted in an increase in visitation to the area from only a few thousand in 1933 to almost 50,000 in 1936.

Resorts were enlarged to accommodate the visitor influx, Furnace Creek Inn having to add a second dining room, a larger lounge, and improved furnishings. Furnace Creek Ranch added housekeeping cottages and more cabins. Even the Amargosa Hotel at Death Valley Junction enjoyed a profitable business. All three main Death Valley hotels are important and significant in their own ways. Furnace Creek Ranch is the, oldest establishment, having been founded initially as a supply point for the Harmony Borax Works, producing food for both its stock and workers. It was opened for visitor accommodation in 1933. The Stovepipe Wells resort was built from scratch by H.W. Eichbaum, and first opened its doors in November 1926. Its success helped encourage opening of Furnace Creek Inn in February 1927 by the Pacific Coast Borax Company.

Since then the different hotels have enlarged and expanded their services and facilities. Today they are the main supply centers in the area and are smoothly and professionally run operations, catering to thousands of. visitors annually by providing accommodations, food, books and literature on the region, and generally performing a valuable service in helping acquaint visitors with the inspiring beauty and absorbing and romantic history of this once formidable part of California.

2. Stovepipe Wells Hotel

a) History

(1) Old Stove pipe Wells

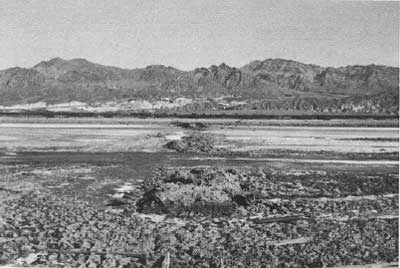

Long before the present Stovepipe Wells resort was conceived of as a viable tourist operation, the site now referred to as old Stovepipe Wells was a life-saving source of water in the arid desert land of northern Death Valley. Situated on the eastern edge of the sand dunes about five airline miles northeast of the present hotel site, these two shallow pits dug into the sandy floor were undoubtedly originally utilized by the Indian inhabitants of the valley prior to the memorable trek of the '49ers that opened the country to white penetration. Their central location would have made them accessible to Indian groups either crossing between the Amargosa Desert and the Cottonwood Mountains via Daylight Pass, or traveling north or south along the valley's central axis. Originally unmarked, and its whereabouts often obscured by layers of blown sand, the well's location was probably first known only through word of mouth, making its detection by thirsty prospectors wandering up and down the valley an. often desperate and time-consuming task. Eventually it occurred to some enterprising individual, who had access to the necessary materials, to stick a length of stovepipe a few feet into the water source and thus insure easy discovery of the site from all directions. [3]

Heavy usage of the well by white men did not actually occur until the mining booms, in Rhyolite, Nevada, and Skidoo, California; the intense excitement and awareness of commercial opportunities they generated initiated a steady and continuous stream of travel over the intervening sixty miles or so of steaming desert. In such a desert environment all springs and water sources are cherished, but Stovepipe's location halfway between Rhyolite and Skidoo seemed to make it a natural waystation for the area also. Sometime probably early in the 1900s a first attempt was made to make of the wells something more than a brief rest stop.

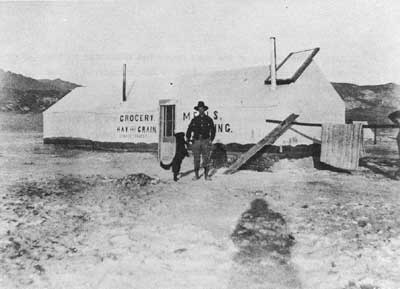

Sensing that the increased traffic along here could become a source of revenue, some hardy businessman or inventive prospector dug himself a cellar space out of the shifting sands, measuring about eighteen by twelve feet, which he then surrounded on three sides with four- to five-foot-high walls fashioned from beer bottles stuck together with mud. Several inches of earth over tarp-covered timbers insulated the roof. from the burning desert sun. Initially concerned only with dispensing a limited assortment of foodstuffs along with a liberal amount of beer from the Tonopah brewery (kept reasonably cool in a tub covered with soaked sacks or tarps), the proprietor soon acquiesced to repeated demands for cool lodging facilities and installed two beds in his cellar for use by overnight visitors.

The water available from the wells was not what would be termed delightfully refreshing, as discerned immediately from one man's account of his experiences after drinking the "poisoned water" of Stovepipe Springs:

My canteens were exhausted when I arrived there [old Stovepipe Wells], and I disregarded the admonition and drank. The water is very low in the spring, is of a yellowish appearance and intensely nauseating in taste. Its odor is very disagreeable, and it can be smelled for half a mile away. Nevertheless, I filled my canteens, and drank of it while there. As I proceeded on my journey my legs became unsteady and I found it difficult to continue my usual pace. I lay down thinking to gain strength, but no improvement was noticeable. The distance between Stove Pipe and Hole-in-the-Rock is about 14 miles, and I fully realized that it was by all odds a case of make this or die . . . . I struggled forward, my legs becoming more and more uncertain. In addition to this everything was getting dim before me, and I appeared to be rapidly losing my eye sight . . . . I could no longer walk and the only means of locomotion left me was to crawl on my hands, and knees. I was almost blind, too . . . . I was 36 hours in making the 14 miles between the two points, and it looks more like a miracle than anything else that I am. alive to tell the tale. [3]

|

| Illustration 256. Bottle dugout, old Stovepipe Wells, in the 1920s. From Margaret Long Collection, courtesy University of Colorado Library, Boulder. |

With the initiation of stage and freight service between Rhyolite and Skidoo in 1906, it became apparent that a more permanent and better-stocked waystation was needed to adequately provision and succor the additional travelers. By February 1907 Stovepipe Wells, in addition to being the one-night stopover on the Kimball Bros. stage route between Rhyolite and Skidoo, was also the first telephone office in the valley. According to J.R. Clark, superintendent of construction on the Skidoo-Rhyolite road and one of the proprietors of the Stovepipe roadhouse,

affairs at Stovepipe are more than satisfactory. There is a commissary tent, a boarding house, lodging house and several additional tents, a corral and feeding stable and accommodations in every respect for pilgrims crossing the hot sands. The spring is now inclosed and the water is consequently much improved . . . . The water is the only fresh water within several miles . . . . The road house at this point is an absolute necessity and facilitates travel from Rhyolite, providing a stopping point at the end of an easy day's drive. [5]

Two months later improvements to the complex were being made, and a feature article on the station in the Rhyolite Herald's pictorial supplement presented a clear picture of what services could be expected there:

The rusty stovepipe is gone, and there stands in its place a full-fledged road house, way down in the depths of the desert isolation. Many a prospector, tired, worn and weary, has travelled far to the protection of this water hole, marked only by the single piece of pipe; perhaps many a prospector has drunk from its slimy waters never to rise again, being too faint, too famished, to consider the advisability of bailing out the hole and waiting for a fresh supply. The water at Stovepipe is good., provided it is frequently drawn off, but alike most desert water holes it soon becomes stagnant and unfit for use. The coming of the road house has eliminated all the bad features of the water, which is now considered of the best.

The Stovepipe road house is quite an up-to-date place. The, equipment includes a grocery, eating house, .bar, lodging house, corral, stock of hay,, grain and provisions,--a little community in itself where travellers may find rest and food for themselves and their beasts. Just now, decided improvements are in progress. A fly is being added to the main tent, walls are being dug, bath room installed, and a pump is being placed to take care of the water. Hammocks will be added for the comfort of guests. Good accommodations have been provided for ladies. Free water is furnished, and every day the place is alive with freighting outfits, etc. going between Rhyolite and Skidoo. Stovepipe is 25 miles from Rhyolite; the half-way station. Meals are 75 cents; beds, 75 cents. The telephone. connects Stovepipe with the outside world, via Rhyolite. [6]

|

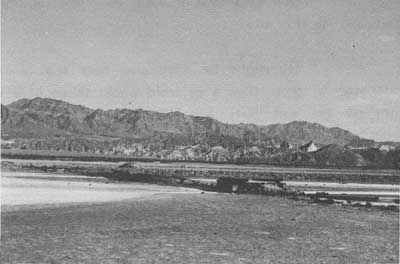

| Illustration 257. Stovepipe Wells waystation, taken by Veager and Woodward on Death Valley Expedition, 1908. Photo courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

| Illustration 258. Present old Stovepipe Wells site. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

Perhaps showing signs of getting carried away with the success of their venture, the owners of Stovepipe were Seven contemplating eventually turning the area into a winter resort:

The water is believed to possess great medicinal properties, the winter is as a delightful spring, and with the addition of comfortable bungalows, houses of entertainment, out door games, on the hard baked sands, and many other features that might be added, Stovepipe could be made a place where those in delicate health or suffering from pulmonary troubles, might find permanent relief. If the sun cure has merit, it could be worked to the limit at Stovepipe. . . [7]

With the gradual decline of Skidoo and Rhyolite as great mining centers around 1908 came the simultaneous demise of the Stovepipe Wells waystation and its gradual abandonment. The article above, however, was certainly a portent of things to come, but it was not until nineteen years later that a young engineer from southern California was able to bring the project to fruition.

(2) Eichbaum Toll Road Brings Visitors to Death Valley

Herman William Eichbaum, born in Pennsylvania in 1878, received a degree in engineering at the University of Virginia before the lure of the West brought him to Rhyolite, Nevada, during its initial bonanza days. Blessed with an open and inventive mind, Eichbaum's engineering talents soon surfaced with his design and construction of the first electric plant in that young city in 1906. Soon turning to mining exploration of the Ubehebe and Goldbelt areas, Eichbaum acquired a taste for prospecting and an appreciation of the beauty and potential of Death Valley that stayed with him all his life and that eventually determined the direction of his future endeavors. When Rhyolite faded, Eichbaum went to southern California where he eventually married a society girl, Helene Neeper, and turned his inventive talents toward creating popular recreational activities on Catalina Island and at the seaside resort of Venice.

During his sojourn in Death Valley Eichbaum had envisioned the recreational potential of the area and had dreamed of constructing a resort among the buttes east of the sand dunes and overlooking Stovepipe Wells. Now, bolstered by several years experience in catering to the public., and well-versed in what the public demanded in its entertainment facilities, Eichbaum determined to make his dreams of opening up Death Valley to tourism a reality. Rejected by the Inyo County Board of Supervisors when he petitioned to construct a toll road from Lida, Nevada, into Death Valley via Sand Spring, Eichbaum alternatively proposed a route over Towne Pass. But still the supervisors were loathe to contribute at taxpayer's expense to what seemed to them such an ill-conceived venture.

Undaunted even after another application was voted down, this time for a franchise to build two toll roads at his own expense, and in an effort to alleviate previous objections, Eichbaum revised his plan to include only construction of a road from Whippoorwill Springs (Darwin Wash) across the Panamint Valley and over Towne Pass to old Stovepipe Wells. [8] Supported by a petition signed by several hundred persons, including representatives of the borax company and even Death Valley Scotty, Eichbaum's application was at last granted by unanimous vote. [9]

Although getting this far must have seemed quite a project to the young visionary, the hard work was only just beginning. After three viewers appointed by the Board of Supervisors, in consultation with an engineer selected by Eichbaum, had decided on the route over Towne Pass and the best method of building the road, construction work began:

A Mr. Miller, Eichbaum's right-hand-man, was superintendent over a crew of six to eight men, including a driver, a grader, several rock throwers, and a cook. Few of them stayed throughout the job . . . . The first road cut was made by a 30-Caterpillar tractor pulling a seven-foot road grader. Then it was widened to a passing width. Rocky outcroppings often determined the width of the road as well as its contour. No blasting was done. As one of the crew described it, they "kinda detoured around" the rough canyon of the present route toward the summit. [10]

In spite of frustrations over mud and washouts that often delayed supplies and construction work, the labor slowly progressed. The floor of Death Valley was reached by spring, and attempts we're then made to clear and grade the roadbed on through to the east side of the valley. It, was not long, however, before the futility of combatting the constantly shifting sands was realized, and the grade had of necessity to be stopped at the sand dunes 4-1/2 miles short of Eichbaum's long-dreamed-of goal. Certification of completion of the toll road was made on 4 May 1926, after which the county supervisors fixed the toll rates between Whippoorwill Springs and Stovepipe Wells as follows: $2 for each auto or motorcycle; 50¢ for each occupant of a truck, trailer, wagon, auto, or motorcycle; $1 per head for each animal, whether driven or led; with rates for trucks, wagons, and trailers to be determined by tonnage. [11] Revenue from the tolls was put in a fund for road maintenance.

The new road into Death Valley, although rough and containing curves that were often difficult for cars to negotiate without considerable backing, was acclaimed for providing direct access to the valley from Los Angeles via Owens Valley, enabling thousands to finally experience first-hand the oft-mentioned scenic splendors and unrivalled panoramas of the region. Eichbaum's immediate plans envisioned sightseeing buses leaving Los Angeles each morning and staying overnight at Lone Pine before continuing on to Death Valley for the next night's stay. The return trip would then be started the following day back to Lone Pine. In addition, Lone Pine was visualizing construction of a road west to the base of Mount Whitney, enabling a one-day ascent of that peak. It was thought that the double drawing-card of visiting the highest and lowest spots in the United States within the space of only a few days would be irresistable to tourists. [12]

(3) Construction of the Resort Begins

With the details of tourist travel to Death Valley worked out, Eichbaum's attention could now focus on construction of his resort, the first unit of which was projected to cost around $50,000, his intention being to add more facilities as the occasion warranted. After Eichbaum's original plan to build a hotel in the buttes east of old Stovepipe Wells turned out to be impractical, an alternative decided on was to initiate construction near the wells themselves. But even this compromise location was doomed to disappointment:

One day six trucks of lumber for the new development were reported arriving at the sand dunes; though we didn't believe it we drove up there to see what it was all about. The proposed route to the Wells lay north of the big dunes and one truck was out there sunk deep in the sand as the others waited cautiously on firm ground for Eichbaum's arrival. He showed up finally, had a long look and then told the drivers to dump their loads where they stood without a chance to reach the wells one place was as good as another. Thus, the site was selected. . . . [13]

It was Eichbaum's contention that in the temperate climate of Death Valley solid frame structures were unnecessary, so the premier unit of his resort consisted of modified tent houses with walls that were beaverboard below and screened on the upper portion, with roll-up canvas awnings available for any further protection against the elements that was deemed necessary. Advertising for the resort and the connecting bus service was immediately started in Los Angeles, stressing such amenities as electric lights, running water, scenic tours, and topnotch service. The original camp consisted of twenty small cabins or "bungalettes" and some larger buildings supplemented with army tents. A revolving beacon light on the roof of the main building served to guide wanderers to the oasis. In these beginning stages of the hotel's development the toll road ran between the main building and the guest cabins and on into the sand dunes.

Bungalette or Bungalow City, as it was familiarly known for a short while, opened for business 1 November 1926, operating on the American plan. The first party of tourists arrived a few days later. Despite the relative luxuries and modern conveniences available here, the basic necessities were still important, and in a manner demonstrating remembrance of the agonies suffered by earlier and thirstier visitors to Death Valley, on 15 November "a crowd of merrymakers dined and danced in celebration of the formal opening of a new 24,000-barrel water well," making possible an additional 1,000 gallons of water an hour. [14]

By the end of November the virtues of the area and of the resort were being extolled in a flowery descriptive tribute by the automobile editor of the Los Angeles Examiner

Death Valley, always mysterious, intriguing and beautiful, until this time has been practically closed to the general motoring public. Now it can be reached and seen in its entirety and in absolute safety[,] comfort, and convenience, either by stage or by private car . . . . It [Stovepipe Wells Hotel] is a city of fifty bungalettes. Their snowy white sides, offset by green and white canvas sun shades, with green roofs, form a vivid contrast. to the gray-black sands. At one end of this bungalette city is a restaurant where a former chief [sic] of the St. Catherine Hotel at Catalina serves tasty delicacies, while radio and Victrolia [sic] entertain. At the other is a store, electric light plant and baths. Across the street men toil with mortar and sand, building tennis courts, a swimming pool, which will be canvased [sic] covered and farther over a nine-hole golf course, plus a landing field for airplanes. This landing field is important, for when completed Eichbaum proposes to put into service passenger planes from Los Angeles, with a combination trip that will make a visit to this country most unusual. [15]

|

| Illustration 259. Eichbaum toll road, showing "Bungalow City" and sand dunes, in the 1920s. From Margaret Long Collection, courtesy University of Colorado Library, Boulder. |

|

| Illustration 260. Stovepipe Wells Hotel. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

Added entertainment possibilities he failed to mention were the trail rides complete with pack animals and with old-time famous prospectors as guides; or for those unaccustomed to. such a rigorous mode of transportation there were large Buick sedans available for sightseeing in comfort. A stage service employing huge Studebaker cars equipped with the latest appointments daily left Los Angeles on tours to Death Valley via Lone Pine. A year-round operation, in the summer the cars took people to Mount Whitney and other scenic spots in the Sierra Nevadas.

By far the largest and most entertaining social event of the year, eclipsing even the opening day, was the Thanksgiving turkey dinner to which all the long-time residents of the valley were invited, the guest list including such notables as Shorty Harris, John Cyte, Bill Corcoran, Jack Stewart, and a host of others. From this time on the resort became a favorite rest stop and gathering point for area prospectors, a place where they knew they would always be welcomed and cared for. [16]

This life Eichbaum had chosen was not an easy one. Despite the widespread and enthusiastic campaign inaugurated to promote tourism in the area, there were still many who remained unconvinced that the desert offered much potential for positive enjoyment. This was especially disheartening to one who was such a firm supporter of the area's natural and historical resources. Another frustration was the basic mechanics of operating an expanding complex in such an isolated area. Most supplies were hauled in from Lone Pine, a long and exhausting trip, while laundry had to be done at Beatty. Because of the salty and brackish content of the water--from the hotel wells, cooking and drinking water had to be imported from Emigrant Spring. Hotel employees were hard to keep in this isolated area, the necessary complement consisting of a clerk, bellhop, cook, two waitresses, and two guides. Some if not all of these workers were evidently blacks, one woman visitor commenting on the "army of colored help all dressed in white duck." [17] The. road was kept in shape by a crew of five maintenance men.

(4) Easter Sunrise Celebration the First of Several New Tourist Services

Probably the biggest boost to tourism in Death Valley was provided by the first Easter sunrise service for the unknown dead of the valley, organized by the Eichbaums to take place on 17 April 1927 in the sand dunes northeast of the resort. The program included a stirring address "dedicated to the memory of the courageous men and women who braved the terrors of the desert in bygone years" [18] and delivered near a large wooden cross set on the crest of the highest sand dune; 100 schoolchildren strew desert flowers over the dunes, the entire program closing with a rousing rendition of "Onward Christian Soldiers" as the sun rose over the Funeral Mountains. [19] The event was so popular and attracted so many people from Los Angeles by private car and motor tour that the service became a ritual each year. [20]

By late October 1927 plans were being made for an ice plant at the resort, and a new unit of rooms being contemplated was to have double walls with a six-inch space between through which cool air would be forced from coils connected to the ice plant. Another ritual repeated this month was the "desert rat" Thanksgiving Dinner, offering the crusty old-timers a tantalizing assortment of delicacies ranging from lobster from Catalina Island to a shank of wild mountain goat in addition to the traditional fowl. How times had changed for the likes of "Johnny-Behind-the-Gun" and "Shorty" Harris! [21]

Two innovations were introduced toward the end of 1929 and beginning of 1930. On 15 December 1929 the first passenger air service into Death Valley was begun. The 350-mile plane tour, in a tri-motored six-passenger sedan, provided its patrons with a view of Yosemite Valley and Mount Whitney before landing on the arid floor of Death Valley. Pack trains and motor cars with guides met the visitors at the Stovepipe Wells landing field and conducted trips to some of the various historical sites in the area. [22] Another enterprise Eichbaum became involved in was the construction of a road to Death Valley Scotty's Grapevine ranch, which would connect with the toll road near the sand dunes, reducing the distance to the ranch and Castle to only thirty-five miles from the present eighty-five-mile route via Beatty and Bonnie Claire. This project opened to the tourist trade not only Scotty's ranch and Castle but also the Ubehebe area, rich in scenic wonders and mining activity. [23] This road led north from the sand dunes toward Cottonwood Canyon, ran by the Indian burial mounds in this vicinity, and then cut across to the western base of the Funeral and Grapevine mountain ranges, which it followed directly to Scotty's ranch and Castle. The later modern highway to Scotty's Castle was superimposed over much of this route.

(5) Toll Road Abolished After Creation of National Monument

It is tragic that the man to whom Death Valley owes so much for its popularizing as one of California's major attractions and most popular winter vacation spots should not have lived to see the region he loved so well become a national monument. A sudden attack of meningitis struck Eichbaum at the age of forty-nine and resulted in his death a few days later on 16 February 1932. A year later, on 11 February 1933, the desolate but beautiful valley that had been the scene of so much hardship and so few rewards for so many became a national monument.

Although Helene Eichbaum was continuing to run the Stovepipe Wells Hotel and toll road, cries were now being heard that toll charges were inappropriate for a national monument and that either the county, state, or federal government should take over the route and remove them. The loudest objections to the tolls were coming from Inyo County residents who, of course, utilized the route more often, and from miners who were currently working claims within the monument and frequently needed to visit them. It was felt that purchasing the road immediately and continuing to use it for a while would give the state time to thoroughly study possible alternative entrances into Death Valley from the northwest that might then connect with other state roads not yet built.

It was hoped at first that the Inyo County Board of Supervisors could be persuaded to purchase the route, it appearing to be the most logical buyer for several reasons: first, Inyo County residents were the loudest protestors to the toll second, acquisition of the road would more clearly define a state route through Death Valley from Shoshone to Independence, thus financially benefitting towns along the highway; and third, Inyo County was more indebted than either the state or federal governments to the pioneer road-building work accomplished by Eichbaum and might be more liberal in the purchase price. [24]

It was the California Division of Highways, however, that finally purchased the 30.35 miles of toll road from Stovepipe Wells to Darwin Wash for $25,000 in December 1934; the seventeen miles of the newly purchased road located within the monument boundaries were subsequently turned over to the NPS. Although the route over Towne Pass was a little too narrow to be easily negotiated by cars and the grades were a bit too steep, the state decided that this was still the only logical entrance point into Death Valley from the west. Only slight changes were made to the route near the summit so that it would be more easily navigable.

The Stovepipe Wells Hotel has gone through several changes of ownership, finally being sold in 1966 by the General Hotel Corporation to Trevell, Inc., a firm operating stores and filling stations in Yellowstone National Park. The NPS has now taken over ownership of the resort. [25]

b) Present Status

The Stovepipe Wells Village complex today offers patio rooms, motel rooms, and deluxe units with a commanding. view out over the sand dunes toward Death Valley. Also present near the main building for visitor pleasure are a swimming pool, restaurant, and cocktail lounge, while across the street are a store, gas station, and a large campground with trailer hookups. Wells drilled in the 1940s now provide potable drinking water. Here and there on the grounds are several relics reminiscent of the monument's early mining days, including an arrastra, ore cars, an old wagon, and even a couple of "mountain canaries."

c) Evaluation and Recommendations

The Stovepipe Wells resort of today, situated in the north-central end of the monument about sixteen miles east of towne Pass and adjacent to the sand dunes, is a far cry from the small tent camp opened in 1926 by Bob and Helene Eichbaum. The rude tent cabins have given way to pleasant air-cooled rooms, while the rough and narrow Eichbaum toll, road has been replaced by a stretch of modern paved highway over which visitors can easily speed between beautiful Owens Valley and the monument. The significance of the Stovepipe Wells Hotel site lies in its association with Bob Eichbaum who first recognized the potential of Death Valley as a winter resort and spent thousands of dollars turning it into one of California's major tourist attractions. Until his efforts were begun, Death Valley was for all intents and purposes inaccessible to the general motoring public who were deterred by the lack of good roads and of dining and sleeping facilities in the area.

By expending a considerable amount of time and money on advertising and on initiating sightseeing tours in this desert region, Eichbaum was able to attract the Los Angeles crowd, whose utilization of the area as a winter resort, Eichbaum knew, would ensure a prosperous future for the valley whose beauty he wished all to enjoy. Eichbaum's interest in encouraging the tourist trade in the area was certainly not mercenary; he probably never totally regained reimbursement for all his many expenditures. His dedication to good service is shown by the fact that he even kept a crew at Stovepipe through the summer months when the resort season was over to provide aid for those inexperienced visitors who might enter the valley and become victims of the heat. [26]

Because of this and similar altruistic actions on the part of both husband and wife, Eichbaum was one of the valley's best-liked residents, beloved by tourists and prospectors alike. The debt owned him by the monument and by Inyo County residents, to whom his business ventures incidentally brought added profit through increased traffic in the Owens Valley area, is immense. He truly fulfilled his vision, conceived during his early prospecting days in the Panamints, "that some day he would go back and open Death Valley, with its beauty, its mystery and history to the world." [27]

The Stovepipe Wells Hotel site was recommended for inclusion on the National Register as being of regional significance. The publicizing of the hotel as the first resort in Death Valley lured vast numbers of tourists there, whose delight in the area and appreciation of its natural and historical resources eventually led to designation of the area as a national monument. The present buildings on the site, however, are not historically significant, having been extensively remodeled and changed over the years. The placement of an interpretive marker on the resort grounds giving some of the hotel's early history is recommended. The Eichbaum toll road (present California State Route 190) has been nominated to the National Register as being of regional significance. Portions of the original trace can still be seen near the modern resort structures. The old Stovepipe Wells site on the 3-1/2-mile-long unpaved road connecting State Highway 190 and the Scotty's Castle road, is also eligible for nomination to the National Register as being of local level of significance. It functioned as an important early waterhole and later was the site of an essential waystation serving the freight teams, passenger stages, and pedestrians travelling back and forth between Rhyolite and Skidoo in the early twentieth century.

(Note: The Stovepipe Wells Hotel and Eichbaum Toll Road have both been declared ineligible for the National Register by the State Historic Preservation Office due to a lack of integrity.)

|

| Illustration 261. Map showing Nevares cabin, Furnace Creek Ranch, Furnace Creek Inn, Corduroy Road, Shoveltown, and Furnace Creek Wash sites. |

3. Furnace Creek Inn

a) History

(1) Pacific Coast Borax Company Foresees Tourist Potential of Region

In the 1920s, as it became apparent to the Pacific Coast Borax Company that the emphasis of borax mining was swinging away from Death Valley for the present, leaving that region with a still-functioning railroad and comfortable living quarters at °Ryan, it was decided that this might be a propitious time to start encouraging tourist travel to the area in order to make some money off these still-usable facilities. Other factors, too, seemed to assure the probable success of such a venture: first, the main transcontinental railroads were now enjoying a lucrative business transporting visitors to the various national parks and other scenic attractions in the West, imbuing Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad officials with the desire to cash in on some of this trade; second, the apparent success of H.W. Eichbaum's enterprising venture at Stovepipe Wells further north was a strong indication of the enormous attraction that this seemingly-hostile but greatly romanticized area held for outsiders; and third, the delightful temperatures of the valley during the months from October to May would be a great enticement to people tired of winter's bleakness and cold winds. All these were strong incentives for initiating some sort of tourist operation that could utilize existing materials and buildings and that involved only a minimum of additional expenditure. [28]

The primary concern of the company centered around providing adequate and comfortable accommodations. It was first thought that the natural and easiest solution would be to house people at Furnace Creek Ranch, and plans were accordingly made to add ten or twelve bedrooms plus dining facilities to that place. On further thought, however, this locale seemed too remote from Ryan, and thus impractical as a tourist headquarters. And so, after lengthy consideration of such alternative locations as Ryan and Shoshone, it was finally suggested by a consultant knowledgeable in such matters, who had been imported from the Desert Inn at Palm Springs for just this purpose, that the small mound and former Indian ceremonial area at the mouth of Furnace Creek Wash would be an ideal site. Not only was a good fresh water supply available 6,000 feet up the wash at Travertine Springs, but the view up and down the valley and of the surrounding mountains was breathtaking. The architect Albert C. Martin was hired to prepare plans for a Spanish-style building, and native Panamint Indians were immediately put to work manufacturing adobe bricks for its construction. [29]

(2) Union Pacific and Santa Fe Railroads Encouraged to Promote Death Valley

In these early days of auto travel the surfaced highway east from Los Angeles ended at San Bernardino, with the branch roads to Ryan and Death Valley being so primitive and lonely that people hesitated to travel them. Taking advantage of this timidity, the Pacific Coast Borax Company extensively promoted use of its own standard-gauge Tonopah & Tidewater and narrow-gauge Death Valley railroads. The two transcontinental lines--the Union Pacific and Santa Fe--were then persuaded to promote package tours to the area during October to May. Through-Pullman service in standard sleepers would be offered between Caliente and Beatty and Los Angeles and Beatty on an every-other-day basis, and in either direction. Initially the Pullmans would be run three times weekly, with the service increased to daily runs the following year. New cars were added to the lines to handle the anticipated influx of tourists. Crucero, 220 miles east of Los Angeles in San Bernardino County, was to be the transfer point at which the Pullman cars would be dropped and switched to the T & T tracks for the ninety-six-mile run north to Death Valley Junction. From here visitors would ride the last twenty miles to Ryan via a gasoline-powered combination express and passenger railcar on the Death Valley line. At Ryan large Union Pacific seven-passenger open touring buses used in the Zion-Bryce Canyon tours during their summer season would meet the people and transport them to the Inn. It was advertised that travelers could leave Los Angeles at six o'clock in the evening and be snugly settled at Furnace Creek Inn the next morning. [30] According to the T & T's general agent, cost of the entire side trip, including Pullman fares between Crucero and Death Valley Junction, fares on the Death Valley Railroad between Death Valley Junction and Ryan and return, bus tickets, hotel accommodations for one night at Furnace Creek Inn, and meals for two days, was set at an incredible $42.

(3) Furnace Creek Inn Opens to the Public

Construction of the hotel started in September 1926, and its official opening was held with a minimum of fanfare on 1 February 1927. The structure was only partially finished, and its number of rooms and furnishings soon proved completely inadequate. A stay at the resort included side trips by motor bus to such nearby attractions as Dante's. View, the Devil's Golf Course, Furnace Creek Ranch, Harmony Borax Works, Gower Gulch, and the abandoned borate camp of (New) Ryan, which still evoked considerable interest despite the cessation, of mining activities there. At the latter place the highlight of the tour was a grand ride over the "baby-gauge" railroad, which in former years hauled borax from the now abandoned deposits to the Death Valley Railroad at (New) Ryan. Open-air cars transported fascinated visitors through tunnels, along the precipitous mountainside, and even inside some of the mines where they could actually see tools and equipment left just as they were when mining operations ended.

|

| Illustration 262. Eleven-passenger Union Pacific tour bus used by Death Valley Hotel Company. View taken in Furnace Creek Wash. No date. Copy of print loaned by Stovepipe Wells Hotel, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

During its first year of operation, Furnace Creek Inn consisted only of a main building housing a spacious lobby and pleasant dining room with wings on either side containing bedrooms opening onto a veranda that encircled the entire building. Day-to-day operations proceeded under the experienced and watchful eye of Miss Beulah Brown, summer manager of the Old Faithful Lodge at Yellowstone. Although the area had not yet been designated for national monument status, such an idea had earlier been proposed, so that both Horace M. Albright, then superintendent of Yellowstone NP, and Steven Mather were consulted during the formulation of plans for the promotion of tourism in the valley. The NIPS was not officially involved in operation of the Inn either, but it was tacitly agreed that it would be operated in about the same manner as other national park facilities. [31]

The tourist business increased steadily, and in the fall of 1927 five more terrace rooms on either side of the parking area had to be added. In fact, new construction at the hotel continued over the next ten years, until the present capacity of about seventy rooms was reached. The following timetable of events is roughly accurate, though sources tend to disagree on some points:

1927-8: terrace rooms built 1928: ten more rooms added 1929: seventeen-room annex completed for employees who had previously been housed in tents and cabins behind the hotel swimming pool and dressing rooms installed 1930: twenty-one-room adobe two-story north wing connected to main hotel; stone unit built back of kitchen for Chinese kitchen help 1934: lower lounge and recreation room added, plus gardens and pools between terrace and north wing; twenty-five fan palms planted plus Deglet Noor palm seedlings from Ranch 1935: four-story central tower unit of twenty-four rooms erected; four ten-room units built for help up the wash from the Inn 1937: two more buildings for employees built; excavation under dining room for bar and cocktail lounge 1938: present garage built 1940: new stone service station built south of garage

Local stone was used in some portions of the complex, the rustic stonework and retaining walls being built by a Spanish stonemason from Madrid, Steve Esteves. [32]

Electric power at the Inn was first generated by four small Kohier units, followed by installation of a 25-KW-capacity pelton wheel across the wash in 1929. As additional energy was required, a 100-hp diesel engine was installed at the Ranch with connections to the Inn, but it proved insufficient for the job. A replacement 225-hp diesel, reinforced by the pelton wheel, was then used until public utility lines were completed.

Abundant fresh water was available at Travertine Springs just up the wash from the Inn. Water was channeled in ditches to a settling box and from there conveyed 6,000 feet downhill in a 12-inch pipe to the pelton wheel at the Inn, which directed it via an open ditch through the grounds, swimming pool, and gardens, and on to the date palm grove and golf course at the Ranch. A plant now recycles up to 100,000 gallons of water a day, enabling it to be used twice. In 1936 a plant experimental station was established at the entrance to Park Village, where botanic experiments were conducted with the objective of growing native shade trees for use at desert villages and resorts. The terraced gardens at Furnace Creek Inn are a spectacular example of what a plentiful water supply and knowledge of planting techniques can accomplish in an arid region. Domestic water came from Texas Spring to the northeast and was stored in a reservoir for use by both the Ranch and Inn. [33]

Meanwhile, about 1928 the old mine buildings at Ryan east up Furnace Creek Wash were converted into the Death Valley View Hotel. In fact, the baby gauge railroad was first run in connection with its promotion, although later it became an independent tourist attraction on its own, providing visitors with an unforgettable scenic and educational experience. The boost to rail travel so greatly anticipated by opening up Death Valley to the public never materialized, as auto travel became ever more popular. On 1 December 1930 the Death Valley Railroad filed an application with the ICC for abandonment of its thirty-mile narrow-gauge system linking (New) Ryan and Death Valley Junction. No objections being made, operations ceased 15 March 1931. Its tracks were ultimately removed, and in the process one of the large trestles from the shoulder of the Greenwater Range was dismantled and its massive timbers used for beam framing in the bar at Furnace Creek Inn. [34] This termination of service left the Ryan hotel completely isolated, forcing its closure in January 1930. The Gowers, who had been running it, moved to the deserted mill town of Death Valley Junction, where they remodeled the old company dining room and dormitories into the Amargosa Hotel, open to the public. This establishment never reached the status of a resort, but did serve as a pleasant overnight rest stop. The Ryan hotel was now used only as emergency housing during crowded holiday seasons, such as Easter week of 1936. (New) Ryan was virtually uninhabited now except for a caretaker, but the baby gauge continued carrying passengers for twenty more years, being discontinued finally in the 1950s.

(4) Sightseeing in the Valley

Prior to the proclamation of Death Valley as a national monument on 11 February 1933, highways in Death Valley were constructed and maintained by the county and private interests, the borax company having been able to accomplish only occasional light work on them. With the advent of the federal government on the scene, highway work was rushed through, with much help provided by the CCC, and the approach routes were taken over by the California State Highway Commission. The state soon completed blacktopping the surface of a main route from Baker, California, via Death Valley Junction to the east boundary of the monument. It also surfaced all but thirty miles of the highway from Lone Pine to the western boundary of the monument. The NPS then hard-surfaced the road between the east and west boundaries, thereby finishing a safe and comfortable route between Baker and Lone Pine that became a heavily-used communications link between the Owens Valley and eastern Inyo County.

This improved roadwork immediately generated heavy auto travel, causing the Union Pacific to pull out of the tourist trade here in the early 1930s. For a while the borax people conducted their own sightseeing tours by means of an automobile passenger line known as the Death Valley Transportation Company, using local cars and employee drivers. This company was intended both as a motor passenger and freight service operating not only between Death Valley Junction and Furnace Creek Inn, but also along the Grapevine Canyon road to Bonnie Claire, Nevada, and on the Daylight Pass road to Beatty. Soon an agreement was concluded transferring the Death Valley Transportation Company franchise to the Hunter Clarkson Company, a Santa Fe Railroad subsidiary that previously operated cars out of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Despite their attempt to provide luxury tours, complete with a fleet of open Cadillacs driven by men attired in Western garb accompanied by women guides, the market was simply not there, and the Santa Fe also pulled out after only two seasons, convinced that the delight people experienced in driving their own cars through the beautiful scenery was a feeling too powerful to overcome. What little touring service was required was supplied thereafter by smaller private companies. [35]

|

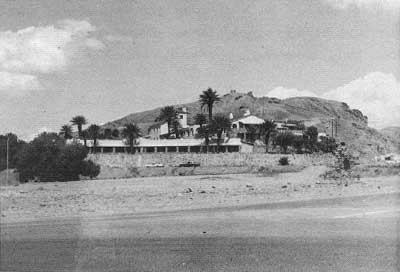

| Illustration 263. Aerial view of Furnace Creek Inn. Photo courtesy of G. William Fiero, 1976. |

|

| Illustration 264. Furnace Creek Inn showing stonework. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

In 1956 Fred Harvey, Inc., took over management of the Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch for the borax company; since 1969 Harvey, now an Amfac affiliate, has owned both establishments.

b) Present Status

Today the Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch are the largest resorts in Death Valley, the former being the more luxurious of the two and operating from October through May. Its sixty-seven units offer superb accommodations on the American plan, and in addition such services and recreational opportunities as beauty and barber shops, formal dining room, cocktail lounge, gift shop, golf, swimming, tennis, horseback riding, and hiking.

c) Evaluation and Recommendations

Furnace Creek Inn is the only one of the three resorts within Death Valley that has gained architectural significance by retaining most of its exterior structural integrity.

The basic layout of this Spanish-style complex has changed little, except to increase in size, since its construction in the 1920s.

The Inn ranks in importance with Stovepipe Wells in not only pioneering in the tourist industry by opening up an entire new scenic area for public enjoyment, but also shares credit for enhancing the state's reputation as a beautiful and enjoyable winter playground. The Inn's associations with the two transcontinental railroads and several touring services during its early years spread Death Valley's fame widely and finally introduced vast numbers of people to the central and southern sections of the monument.

The resort also is significant because of its connection with the borax industry and its promotion of tourist development at Ryan; it was even able for a short while to prolong that town's existence as well as that of the narrow-gauge Death Valley Railroad. Because of their interest in keeping tourist routes open to and throughout the valley, the borax employees were largely responsible for constructing and maintaining the monument roads during these years.

Due to its continuing role as a tourist facility that for over fifty years has helped promote California's attractions as a winter resort area, and because of its architectural and site integrity, the Inn appears to meet the criteria of eligibility for the National Register as being of regional significance. The resort should be marked by an interpretive sign briefly presenting the structure's history.

4. Furnace Creek Ranch

a) History

(1) Greenland Ranch Supplies Food to Borax Workers and Serves as Mule Train Depot

The industrial phase of Death Valley history began with the discovery of borax there by Aaron and Rose Winters and the subsequent purchase of their claims by William T. Coleman in the early 1880s. After establishing a location for his open-air borax refinery about 1-1/2 miles north of the mouth of Furnace Creek, Coleman next addressed the need for a supply point to provide essential provisions for his mules and for his workmen at this plant and at his Amargosa works. [36] A logical place for this operation was the spot near the mouth of Furnace Creek Wash that had been homesteaded in the 1870s by one "Bellerin" Teck, an unknown and still vastly mysterious figure who live there for a short while, raised alfalfa and barley, and then seemingly disappeared from the annals of history.

The ranch consisted of a large adobe house with a wide northern veranda, and was first referred to as "Greenland" and occasionally as "Coleman." It was given its present name by the Pacific Coast Borax Company sometime after 1889. It is recorded that about 1879 Coleman, enjoying a certain affluence at this time, sent to Italy for gardeners to supervise agricultural development of the site. At great expense the soil was scientifically fertilized and various types of trees planted in the resulting dark and heavy loam. A half-acre pond was constructed and water from the Funeral Range was diverted from Travertine Springs to the ranch via a stone-lined ditch to irrigate thirty or forty acres of alfalfa and trees.

With about forty men actively employed at the borax works, and considering its vital function as a terminus station for the twenty-mule teams, where wagons could be repaired while men and animals enjoyed the luxury of a few days' leisure after their exhausting round-trip haul to the railhead, the ranch became an important center of operations. Under the guardianship of James Dayton and by dint of constant irrigation, livestock flourished in this barren desert, as did the growth of melons, vegetables, alfalfa, figs, and cottonwoods. The presence of water, shade trees, and grass in the area led to temperatures that usually ranged from eight to ten degrees cooler than elsewhere in the valley, and by 1885 the farmstead was rich in alfalfa and hay, while cattle, hogs, and sheep were supplying fresh meat for the tables of the Harmony borax workers.

(2) Pacific Coast Borax Company Takes Over Ownership and Ranch Becomes Friendly Oasis for Prospectors

The promotional possibilities offered by this cool oasis greatly appealed to Coleman, who at one point envisioned eventual establishment of a resort here. These dreams were rapidly deflated by the downward spiralling of his economic fortunes, which ultimately forced him to mortgage all of his holdings to Francis M. ("Borax") Smith and eventually lose them all to that great entrepreneur in 1890. Smith's stewardship began with the closing of both the Harmony and Amargosa borax works, his business efforts now being concentrated solely on his new mine at Borate. Jimmy Dayton, however, remained as watchman for the borax plant and caretaker of the ranch farm. Some idea of the style of life he led here can be gained from the following account of a visit to his headquarters:

He [Dayton] cooks his food in a frame kitchen and sleeps in an adobe bedroom. The walls of the bedroom were plentifully adorned with lithographs of young women, such as the tobacco-makers distribute gratis. Two shotguns and a rifle stood in one corner. A prospector was keeping the house for Dayton during the latter's absence, and every day I was there he killed, with the shotgun, numbers of duck, teal, butter-ball and mallard, which, in their journey from the north, came down to see what kind of feed could be had on the alfalfa meadows, and in an artificial, half-acre fish pond at one corner of the oasis. The rifle is sometimes used on the sheep in the Funeral range to the east . . . . Had we wished, we might have had carp from the pond, which was stocked some years ago, while flocks of quail were seen in the brush about the fields. [37]

Initially Smith displayed none of Coleman's enthusiasm for creating a resort or other type of vacation spot at the ranch, and ran it solely as a commercial venture. As the shade trees grew and the fruit trees prospered, the spot turned into a friendly oasis frequently visited by prospectors and other wanderers in need of rest and refreshment. The buildings were improved and new tropical trees planted, but otherwise little change in the general layout resulted.

Dayton served as caretaker and foreman of the ranch for about fifteen years, until his death in 1900. By the early years of the next century one Oscar Denton had taken over his duties, and with the help of local Indians was continuing to raise alfalfa and figs. After the turn of the century, the ranch was the scene of increased activity as dozens of prospectors combed the nearby ranges as part of the new southern Nevada mining boom centering around Tonopah and Rhyolite and their environs. The ranch was the resting place where these "desert rats" could lounge beneath the trees and bathe in the ditches white awaiting supplies ordered to be sent to Denton from Death Valley Junction. This was

the place to which everyone went whenever loneliness overcame him and he needed human association and conversation. The old time Death Valley prospectors traveled alone, their burros the only companionship they had. Without Furnace Creek Ranch, Oscar Denton, and the Panamint Indians, Death Valley would have been intolerable. [38]

(3) Precautions Necessary Because of Unbearable Summer Heat

There were, however, a few drawbacks to life at this veritable shangri-la, not the least of which was the intense °summer heat. The 1883 report of the California state mineralogist attempted to describe the difficulties experienced by residents of the Furnace Creek area:

The atmosphere presents many peculiar features, among others, causing a feeling of lassitude and weariness and an intense thirst upon very slight exertion. Many of those who have been for a month or more residents of the valley complain of an affection [affliction] of the eyes, which become sore and weak . . . . During the visit of Mr. Hawkins, in May and June, 1882, almost every afternoon a burning wind, fierce and powerful, sprang up, blowing articles of considerable weight some distance, and hurling the coarse, hot sand with such force as to lacerate the face when exposed, the men being frequently obliged to wear veils and goggles. The heat was severe, the thermometer averaging from 95° to 100° Fahrenheit in the shade . . . . The stones and cement became so hot by ten o'clock A. M. that work was suspended until late in the afternoon, and at night the men frequently rolled themselves in thoroughly wet blankets in their endeavors to keep cool. [39]

A New York reporter who visited the spot in the early 1890s presents a vivid description of the consequences of the environment and the effort necessary to survive the extremes in temperature:

While making the ditch which supplied the ranch with water, J. S. Crouch and O. Watkins slept in the running water . . . . Philander Lee . . . while at work on the ranch, regularly slept in the alfalfa where it grew under the shade of some willows and was abundantly irrigated.

Other effects of the arid air are found in the utter ruin, within a few days, of every article of furniture built elsewhere and carried there. . .

Meat killed at night and cooked at 6 in the morning had spoiled at 9 . . . . Eggs are roasted in the sand. [40]

The ranch's location 178 feet below sea level on the floor of the valley and at the foot of the Funeral Range, (making it the lowest place in the western hemisphere where vegetation thrives), promotes such a constantly warm environment that young palms and other tropical plants had to be set in the shade of houses or older trees to ensure their survival. In summer, activity on the ranch ceased during the daylight hours, the enervating atmosphere making all but the most perfunctory tasks impossible. Mostly time was spent lounging in hammocks hung across the wide veranda. Water bags within arms reach provided necessary periodic relief. Harry Gower mentions dining with Oscar Denton on the ranchhouse porch in the breeze generated by a five-foot fan revolved by water power. [41] The pervasive stillness of the day, however, was in contrast to the evening bustle, when ranch chores were performed and the more pleasant aspects of life--eating, drinking, and playing cards--were indulged in with gusto.

The products of the ranch were being continually improved over the years. In 1906 it was noted that

One of the most wonderful sights in Death Valley is the Furnace Creek Ranch, owned by the Pacific Coast Borax Company. They can raise almost anything there. They have fresh eggs and milk the year round. The weary prospector may put his hungry burro in the corral, and fill him up with good alfalfa for 35 cents per night. There is plenty of water, over fifty inches running in the ditch, and more in a pipe line. [42]

Around fifty head of cattle were being raised and five crops of hay gathered a year. The poet-prospector Clarence Eddy wrote during a visit to the ranch that for four bits a head one could eat fresh eggs, lettuce, turnips, carrots, parsnips, and pumpkin pie, plus real cow's milk. In July 1907 the only white man present at the ranch was reportedly a W.A. Northrop who continued the cultivation of watermelons, muskmelons, corn, alfalfa, and cantaloupes. [43]

(4) Indian Population

One interesting aspect of life on the ranch was the Indian population that gathered there. Furnace Creek had habitually been a social center and contact point for three linguistic groups: the Shoshonis from the north, the Southern Paiutes from east of the valley, and the Kawaiisu from southern Death and Panamint valleys. [44] After John Spears had stopped at the ranch in 1892 he described the following visit by a neighboring Indian and gives some indication of their lifestyle:

While at the ranch it was visited by a native sportsman--a little black, dirty Paiute. He was dressed in cast-off clothing of white men, and was armed with a bow and three arrows. The bow was of juniper, backed with raw sinew, and the arrows were of reed, tipped with juniper. They were effective against rabbits, rats, and lizards, and so satisfactory to the Paiute sportsman . . . . The Indians had burned some acres of mesquite and brush along Furnace Creek in their hunting for rabbits and rats. There is very little meat about them, but everything is fish that comes to the Paiute net, including the kangaroo rats. [45]

|

| Illustration 265. Pacific Coast Borax Company's Furnace Creek Ranch, about 1909. From Rhyolite Herald Pictorial Supplement, March 1909. |

The Indians employed as ranchhands were described by a desert photographer, Clarence Back, in 1907 as being extremely uncommunicative, often not speaking to their employer for weeks.

In 1910 George Bird Grinnell described Indian women and children in April trapping rodents and lizards in the mesquite thickets around the ranch, catching them in deadfall traps or nooses and boiling them in kettles. [46] In 1922 Edna Perkins described the "Panamint" Indians living at the ranch in this manner:

The Indians . . . are employed as laborers, when they will work. The superintendent, a vigorous, silent Scotchman, was extremely pessimistic about them. While we were there they had "the flu" and all we ever saw them do was sit around the corral waiting for supplies to be handed out. The women and girls, with heavy melancholy faces, gathered and stared at us. They stared with the stolid curiosity of cattle, not like burros who twitch their ears saucily, though they have the burro's reputation for thievishness. The superintendent kept everything under lock and key. The only Indian who showed a sign of life was an old fellow who prowled around with a gun after the birds and wild ducks that make the ranch a resting-place in their flights across the desert. We were told that there was only one gun in the whole encampment and that the younger men hunted with bows and arrows. Most of them looked stunted and their faces were wrinkled like the skins of shrunken, dried-up apples, as though the valley were taking toll of the generations of their race. [47]

(5) Ranch Contemplated as Health Resort

In the fall of 1907 rumors were circulating to the effect that Borax Smith was now entertaining visions of developing his Furnace Creek ranch as a winter resort, and was even contemplating extending a branch line of the Death Valley Railroad to provide access to both his borax deposits along Furnace Creek Wash and the ranch. This plan was amplified somewhat in early 1908 into establishment of a health resort for persons suffering from pulmonary disorders and related afflictions. The climate here, especially the density of the air, its increased pressure, and the higher percentage of oxygen, were all thought to have a curative effect on such diseases. It was said that a large sanitarium plus a hotel and bathhouse would be erected.

By February 1907 the Furnace Creek ranch was described as "a great stretch of green--a magnificent spread of emerald in a grimy, desolate bed of shale and sand." [49] Three hundred acres were reportedly under cultivation, with experiments successfully carried out in growing alfalfa grasses, vegetables, melons, apples, and pears. [50]

(6) Official Weather Station

Back in April 1890 Greenland Ranch had been selected by the Weather Bureau of the Department of the Interior as an official weather station, and it had been duly fitted with rain gauges and a thermometer. In 1922 the U.S. Weather Bureau established a substation here, tests run over the previous ten years having shown that this was the hottest region in the United States. The average of the extreme maximum temperatures reported since 1911 had been 125°F. Almost daily during June to August at the ranch temperatures of 100°F. or higher occurred, with the temperature of 134°F. on 10 July 1913 believed to be the highest natural-air temperature ever recorded with a standard thermometer exposed in the shade under approved conditions. Even the water providing irrigation for the ranch has a temperature of between 74° to 100°F. During this time period the ranch was experimenting with poultry raising in addition to a lucrative business in the production of dressed meat. [51]

|

| Illustration 266. Furnace Creek Ranch, about 1915. |

|

| Illustration 267. Furnace Creek Ranch, 1916. From Dane Coolidge Collection, courtesy of Arizona Historical Foundation. |

(7) Date Growing Introduced

The growth of dates was introduced to the Furnace Creek ranch about 1921 or 1922, supposedly at the behest of Pacific Coast Borax Company officials who suggested it as an added source of revenue. This planned extension of the date industry in a most unexpected direction was arrived at after extensive research conducted by Dr. Walter Swingie, principal originator of the date industry in America. The man who had supervised the successful government date operations in the Coachella Valley of California, Bruce Drummond, was engaged to direct the Furnace Creek venture. In addition to some California native "wild date palms" and specimens of a Canary Island native, selected samples of the ° Deglet Noor (Date of Light) palm were also set out. This latter tree is not native to the New World but was introduced from Africa in 1898. Of the several varieties of soft dates experimented with by the government in these initial years, it quickly proved the hardiest, and now comprises most of the Ranch's present large grove. The site's comparative isolation made it ideal for growing pest-free. stock. In the 1930s fertilizer was trucked in from the Pahrump ranch southeast of Death Valley Junction to be applied to the palms. One major obstacle to their growth, the fact that were were no bees in the, valley, necessitated hand pollination of the trees. Dates have been the principal product of the last fifty years, the other experiments with winter vegetables, cotton, and citrus trees enjoying lesser success. Excellent crops are produced, and the fancy dates are shipped to market and are also available in gift packages at the ranch. [52] During the 1920s the ranch also produced two hundred tons of alfalfa annually that were fed to a herd of high-grade beef cattle that were in turn fed to the men at Ryan.

(8) Ranch Turned into Tourist Resort

In 1930 when the hotel at Ryan closed, the borax company felt that some type of accommodations should be offered in the valley that would be less expensive and of a more relaxed sort than were found at Furnace Creek Inn. Because of their ranch's abundance of water and its level building site, it seemed the logical place for such an undertaking. Eighteen tent houses that had formed the construction camp at the inn were moved down to the site. To these were added several workers' bungalows from the just-completed Boulder (later Hoover) Dam, which were moved to the site and remodeled for tourist use. A 16 x 36-foot boarding house and cabins (now removed) from the abandoned Gerstley Mine near Shoshone were also used to bolster the accommodations.

The Ranch first opened its doors for business in 1933, and for two years the wives of the Ranch foreman and mechanic operated the hotel, which underwent a continual program of enlargement and expansion over the next ten years. The balance of the cabins were built in the period from 1935 to 1939, with the lobby, store, and dining room constructed in 1934-35. In 1936 a building originally erected for drying dates was being used as a schoolhouse for fifteen or twenty elementary schoolchildren. (Also in that year the Ranch was the terminus again for a commemorative run by the U.S. Borax Co. twenty-mule team.) The recreation hail was built in 1936, the kitchen enlarged in 1952, and the office and swimming pool added during 1951 to 1952. [53]

|

| Illustration 268. Date orchard at Furnace Creek Ranch at harvest time. Photo by George Grant, 1939, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

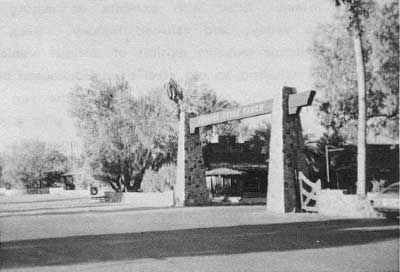

| Illustration 269. Furnace Creek Ranch entrance. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

The advent of World War 11 not only postponed a $150,000 building program for the Ranch planned by the Pacific Coast Borax Company's London offices, including a projected new lobby, dining room, coffee shop, and kitchen, plus new parking facilities and fifty new cabins, but also resulted in a shutdown of services. By the time this took place, however, the Ranch did have accommodations for 350 people, plus a nine-hole all-grass golf course that had been added in 1930 for the Inn guests but that was used equally by Ranch customers. After the three-year hiatus, the Ranch, Inn, and Amargosa Hotel reopened in 1945 and were run for ten years by Charles Scholl. In 1955 they were all leased to the Fred Harvey organization, which decided to concentrate its operations within the valley, resulting in sale of the Amargosa Hotel in 1959. The newest units at the Ranch, located alongside the golf course, were completed in 1975, and' other recreational facilities, such as tennis courts, were completed in 1977. [54]

The highlight of a tour of the Ranch today is a visit to the borax museum, begun in the 1950s as an educational opportunity for guests. The old borax office building from Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon was moved to the Ranch around 1954, and its interior filled with exhibits on mining, Indian populations of the valley, and railroad history. Back of this structure is an outdoor museum exhibit of antique vehicles and mining equipment, including an old steel-tired buckboard belonging to Borax Smith, an early stagecoach used on the run between nearby mining towns, and other assorted wagons, plus a stamp, a ball mill, a whim, the Death Valley Railroad Engine No. 2, and miscellaneous souvenirs such as the small Death Valley Chuck-Walla printing press rescued from Greenwater and the original twenty-mule-team barn moved up from Mojave. On one side of the entrance to the Ranch is Old Dinah--the high-wheeled oil-burning steam tractor used on the Borate to Daggett route for a year or so and then put into service hauling between Beatty and the Keane Wonder gold mine in the Funeral Range. After its twenty-year abandonment in Daylight Pass, it was towed down to the Ranch in 1932 to be added to the Furnace Creek Ranch museum collection. On the other side of the entrance are some borax and water wagons.

b) Present Status

Today this Fred Harvey-owned resort offers simple wooden cabins, fancier pool- and golf-side rooms, and deluxe motel units. Opportunities for recreation are provided, including a beautiful golf course, a swimming pool, and horseback riding, and also available are an outdoor restaurant, a coffee shop, a cafeteria, a general store selling food, books, and souvenirs, a post office, and an airstrip. Trailer and camping sites are located nearby. The resort's location is enhanced by the presence of the National Monument Visitor Center immediately to the north.

c) Evaluation and Recommendations

The site on which Furnace Creek Ranch is now located is one of the most historically significant spots in the monument. Its location near the mouth of Furnace Creek--a steady water supply throughout the year--made possible its development as a farm operation as early as the 1870s. Prior to this the area was probably visited frequently by members of the surrounding Indian populations to the north, south, and east. Little is known of the extent of this early aboriginal activity or of the life of the first Anglo homesteader on the site. The Furnace Creek ranch gained major importance as the supply 'point for the Harmony and Amargosa borax works and as the northern terminus of the twenty-mule-team wagon route between Harmony and the railhead at Mojave. Perhaps its most important contribution, if the many prospectors and other desert travelers in the area during the early 1900s could be polled, was its service in providing shade, water, and some semblance of social amenities in a harsh, often brutal, environment, and its status as a meeting-place where fellow "desert rats" could get together and socialize, swapping stories and dreams before embarking again on the never-ending quest for riches. Initially producing mostly alfalfa and hay for stock, the ranch later raised and dispersed beef to feed workers at the nearby borax camp of Ryan.

An interesting sidelight to the ranch's history would be a determination of the amount of influence it exerted on the development of the various Indian groups who either resided at or visited the ranch. One would gather from the rather scathing comments on the native inhabitants presented earlier in this section that hardly any mingling of the races occurred, but it must be remembered that these observations were made by one-time visitors to the area, and fairly sophisticated ones at that. The more mundane and less "cultured" mining community undoubtedly had daily, and thus more influential, contact with the native population.

The ranch's later evolvement into a tourist resort is not considered notable because the tourist industry had already been given its start by the construction of Stovepipe Wells Hotel and then of Furnace Creek Inn. Most of the early buildings of the complex that were architecturally significant because they were a curious mixture of old mining cabins and construction bungalows imported from surrounding desert communities have long since been removed. The present structures date from the 1930s on. The site should be provided with an interpretive marker presenting highlights of the ranch's early days and pointing out its significant role in Death Valley history.

5. Nevares Cabin and Homestead

a) History

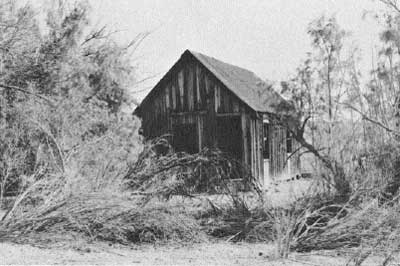

The small undramatic wooden cabin with nearby root cellar that comprises the Cow Creek Ranch are located immediately southwest of Nevares Spring. The site was evidently co-owned in the early 1900s by Adolphus ("Dolph") Nevares, a Death Valley prospector of Spanish-American descent, and Montillus Murray ("Old Man") Beatty. The former was a native of San Bernardino who retained a permanent home there all his life. He worked as a prospector for the Pacific Coast Borax Company in the early years of the twentieth century, acquiring the job mainly because of his part in one of the company's most publicized episodes--the search in 1900 for the company caretaker, Frank Dayton, who was long overdue from a trip into the desert. When he was finally found, the victim of a heart attack or sunstroke, Nevares was appointed caretaker in his place and served in that capacity until his advanced age forced his retirement. While working for the borax company he lived on a homestead near their headquarters at Furnace Creek in a cabin bought at a nearby mining town, dismantled, and rebuilt on its present location. The copiously-flowing spring nearby facilitated the growth of a small orchard in which fruits and vegetables were raised. [55]