|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION III:

INVENTORY OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES THE WEST SIDE

C. Cottonwood Mountains

1. Hunter Cabin

a) History

William Lyle Hunter, born in Virginia in 1842, came to the Death Valley region in the late 1860s. Marrying a girl from Virginia City, Nevada, Hunter subsequently settled down to a life as stockman, miner, and explorer. During the Cerro Gordo excitement he drove a large train of pack mules, realizing a considerable profit from this venture. Exploring widely in the surrounding region during these years, Hunter was among the first to penetrate the Ubehebe section (referred to then as part of the Rose Springs Mining District) in 1875, locating some valuable copper claims there. He and his compatriots are said to be responsible for changing the name of the area to "Ubehebe." In the lush green hills and forested area south of the Ubehebe District, where a variety of springs provide an abundance of water, Hunter grazed the mules and horses he raised and no doubt used in his pack trains. This green swath later became known as Hunter's Ranch Mountain, and was still being used many years later by his grandson Roy as pasture land for his cattle. Among other discoveries made by Hunter and his partner John Beveridge were those of the Belmont silver Mine east of Cerro Gordo and the Beveridge District in 1877. [1]

|

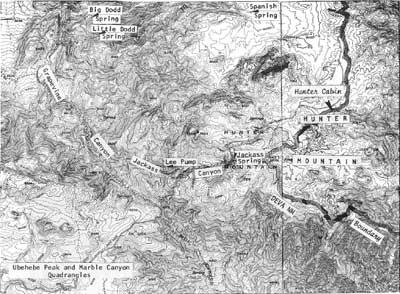

| Illustration 221. Map of Hunter Mountain. |

In 1897 Hunter and Reuben Spear, with whom he worked the Ulida Mine, were still performing development work "on old claims at 'Hunter's ranch.'" [2] The property was at this time crossed by an early mining trail leading east from Keeler to the Ubehebe region. Traversing the Inyo Range south of Cerro Gordo, it crossed the head of Panamint Valley "and finally ascends a superbly wooded and amply watered upland for many years known as Hunter's Ranch." [3] From the area of today's Lee Pump trails led to Saline Valley to the north, to the Lee Flat Mining District to the southwest, and on to Furnace Creek to the southeast via Cottonwood Canyon. Another reference to what is believed to be this area mentions the "several good camping grounds around the nut-laden trees and bunch grass of Hunter's Ranch." [4]

By 1900 Hunter and his family were living at George's Creek south of Independence, where he died in 1902 at the relatively young age of 59. In 1907 water from Hunter Ranch Creek 1/2 mile above Hunter Ranch was filed on for use by the Ulida Copper Company, which intended to pipe the water to its Ubehebe mine. Another location was filed five days later requesting 100 miner's inches on Hunter Ranch Creek 1-1/2 miles above "Indian Garden," the water to be piped to the Ulida Copper Company property for mining purposes. [5]

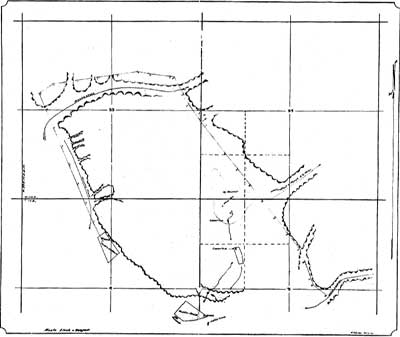

Three early survey maps were found, two of which show an irregularly-shaped plot of ground labelled "Hunter Ranch." The earliest map, dated 1924, presents a confusing array of buildings. It shows, for instance, a "Hunter Ranch" plot, complete with house, nearby Indian camp, and an extensive reservoir system, located between a ranch to the east (probably Steininger's) and another site referred to as "Scott's Old Ranch." The accuracy of this survey is extremely doubtful. Actually what is designated as "Hunter Ranch" on this map seems to refer to what is the Lower Grapevine complex today, with the "Scott's Old Ranch" site located about where the present swimming pond is (see Illus. 222). The township lines shown support this assumption.

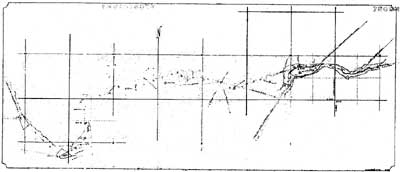

A 1927 survey again shows a Hunter Ranch in the vicinity of an "Indian Gardens" as mentioned in the water location notices filed by the Ulida Copper Company in the early 1900s. Otherwise, the same features are noted as in 1924: a house, an Indian camp site, and the reservoir. No corral complex is shown. On the same plat is the layout of the old Steininger place. The plot referred to on the earlier map as Scotty's old ranch appears on this survey but is unnamed, suggesting that an attempt was made to correct the earlier survey (see Illustration 223). [6] Some puzzling questions remain, however. Julian Steward, in his study on the Indian populations of the Great Basin/Plateau area does not mention the Hunter Mountain region as being home to any particular group of Death Valley Indians, although the presence of "Indian Gardens" might indicate that some occasionally occupied the lush area to avail themselves of the pinyon nuts and cooler air (see Illustration 223). An Indian camp did exist near Death Valley Ranch during construction of the castle, however, to house the Indian laborers. As late as 1955 Hunter's Ranch was sporadically utilized as a cattle ranch. [7]

b) Present Status

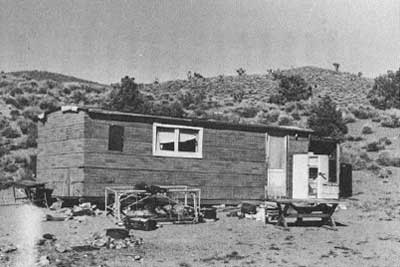

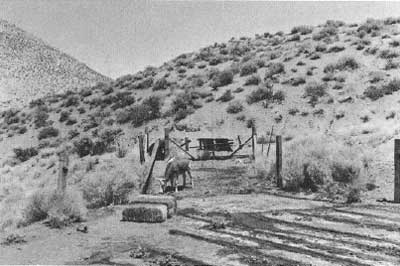

Hunter Cabin is located on Hunter Mountain on the west side of Death Valley immediately inside the National Monument boundaries and about 3/4 mile south of the Hidden Valley road that passes via Jackass Canyon to California State Highway 190. Although not inspected by this writer, the site was visited by the LCS crew in December 1975. Development at the site consisted of a one-room log cabin constructed of pinyon pine and measuring approximately twelve by twenty feet, a spring twenty yards uphill that had been opened up into a watering trough, and a primitive corral about one hundred yards northeast of the cabin. Visitors obviously have used the area in the past as a campground.

c) Evaluation and Recommendations

Either a "Hunters" or a "Hunters Ranch" is located on the "Itinerary of Scout made by Co. D, 12th U.S. Infantry, Commenced April 30th and ending May 25th 1875," the "Itinerary of Scouts made by Co. "D," 12th U.S. Infanty [sic] during May, June, July and August 1875," and "Route marched by Co. I, First Cavalry, Commanded by Capt. C. C. C. Carr, First Cav. from June 8th to June 25th [1875]." [8] According to Levy, however, the present Hunter Cabin was built by a "packer" named John in 1910, using materials salvaged from an earlier cabin at Lee Pump. [9] That place, however, is west of Jackass Spring, while the ranch site shown on the military reconnaissance maps is definitely east of this waterhole, implying that some sort of ranch layout existed at this precise location as early as 1875. The ranch area as far as can be ascertained was primarily used for grazing of the mules and horses that Hunter used in his pack trains or supplied to the army. [10] It is doubtful that it was ever occupied for any extended period of time, but was instead used mostly as a line camp.

|

| Illustration 222. Map dated 1924 showing "Hunter Ranch." From history files, DSC. |

|

| Illustration 223. Map dated 1927 showing "Hunter Ranch." From history files, DSC. |

|

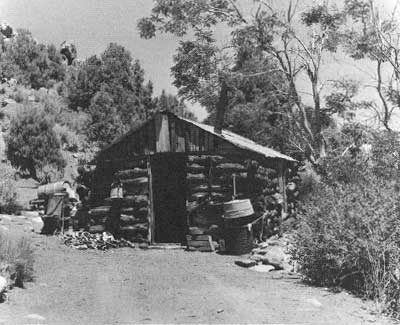

| Illustration 224. William Lyle Hunter cabin located just inside monument boundary northeast of Hunter Mountain. Later lived in by Bev Hunter. Photo by Wm. C. Bullard and Dan Farrell, 1959, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

| Illustration 225. Corral complex at ranch, 1959. Photo by Wm. C. Bullard and Dan Farrell, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

The Hunter Ranch complex is of more than passing interest for several reasons: first, because it was built by W. L. Hunter, father of one of Inyo County's foremost pioneer families and a founder of the Ubehebe Mining District; secondly, because of its location along an early historic military route from Camp Independence to Nevada, which later became a heavily-traveled trail into the mining areas of northern Death Valley, and because of its reputed status as a supplier of horses to the army troops; and thirdly, because of its interesting construction of pinyon pine logs. Because insufficient data exists to properly evaluate the ranch's role in Death Valley history or to justify placement of it on the National Register, it is recommended that it be accorded treatment of benign neglect. Camping in the area should be discouraged in order to lessen the dangers of fire and vandalism.

Hunter Ranch is one of only two small early homestead or ranching cabins viewed by this writer during survey trips to Death Valley, the other being the Nevares Cabin near Cow Creek. The Hunter cabin appears more rustic than the other, being built of pinyon pine logs squared on three sides to ensure a tight fit. Some of these have been spliced together because they were not long enough to extend the entire wall length. The cabin rests on a stone foundation on the downhill slope and directly on the ground on the other three sides. Other features of construction include: a one-by-two plank floor, square-cut corner log joints, rag chinking, a corrugated-iron roof resting on a pole frame, and a board-and-batten gable. Although somewhat protected by its location in a thick pine forest, a few conditions are leading toward the cabin's ultimate demise: decaying logs, an unstable floor, a loose roof, insect infestation, and water seepage from the nearby spring.

2. Ubehebe Mining District

a) Copper Veins Attract Attention

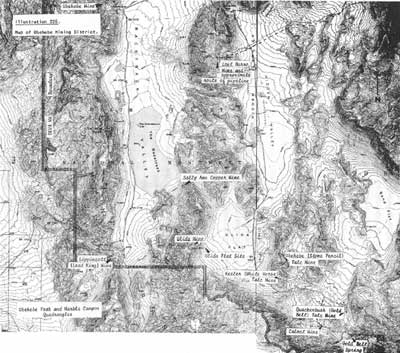

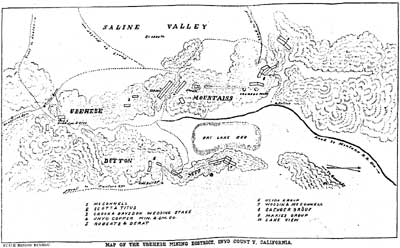

Located in one of the most remote and beautiful corners of the monument, the initial claims of this area were first discovered in the summer of 1875 by W. I. and J. B. Hunter, Thomas McDonough, and J. L. Porter. The Ubehebe mineral district, about thirty-five miles northeast of Keeler, includes an area about eighteen miles long by thirteen miles wide, bounded on the west by Saline Valley, on the south by spurs of the Nelson Range extending east to Hunter Mountain, on the east by the Cottonwood Mountains, and on the north by the southern end of the Last Chance Range. Two smaller mountain systems span the area north to south, the Ubehebe Range on the west being separated from the Dutton Range on the east by a two-mile wide valley containing the dryed-up lake bed known as the Racetrack. The exact derivation of the name "Ubehebe" is unknown, although it is thought to. be Shoshonean, meaning "big basket." It has been variously translated as "basket in the rock" or "basket in the sand." [11]

|

| Illustration 226. Map of Ubehebe Mining District. |

The principal find of the 1875 explorations in the area was an enormous eighty-foot-wide ledge of copper, referred to as the Piute Lode and showing ore assaying 15% to 67%. Immediately after its discovery on 2 July, Porter began experiments to determine the best method of ore reduction, ultimately concluding that it could be smelted profitably right on the grounds. [12] The famous Cerro Gordo Mine near Keeler was in a very prosperous condition at this time, and probably encouraged by its success and the general air of prosperity in the area, M. W. Belshaw, operator of a smelter at Keeler, purchased at least a portion of Hunter and Porter's Ubehebe properties that year and proposed erection of a smelting furnace on the edge of Saline Valley before early spring. This goal was never achieved. [13]

For many years thereafter little work was performed on the large and promising copper veins of the Ubehebe district, the problems characterizing all desert mining--lack of water and wood near the deposits, their isolation from rail centers and supply points, the difficulties of constructing and maintaining adequate roads through a hostile environment, the uneconomical methods of ore removal and transport--being present here in abundance. Reportedly the famous New York artist Albert Bierstadt became interested in the Ubehebe mines around 1886 and spent several days examining them. Although he made definite plans to purchase some property, for unknown reasons the deal was never consummated. Perhaps he too realized the many factors still militating against the success of mining ventures in the region. [14]

Not until the late 1890s did activity surface again. In 1897 a W. J. Ryan of Denver, representing Mr. N. O. Moore, one of the country's leading mining experts, bonded the copper mines of A. F. Mairs and J. F. Welsh for $15,000, with the promise that active development would commence immediately. True to his word, by early March Ryan had departed for the mine with a load of provisions and supplies to sustain the eight-man crew he intended to set to work on a large vein that showed promising amounts of gold as well as of high-grade copper. [15] Undeterred by the area's remoteness, Moore was overly and prematurely optimistic in his assurances that a railroad would penetrate the area if the copper deposits proved as extensive as they appeared. The first serious mention of a railroad connection again concerned the Randsburg Railway, which at this time stretched from Kramer station on the Santa Fe and Pacific only as far north as Johannesburg. If the line was extended to Keeler via Ballarat, it had been suggested, it could service also the Wildrose and Lemoigne Mine areas. A thirty-mile wagon road constructed from the Cottonwood Mountains south to some agreed-upon point on the line would then open up the Ubehebe copper region and provide the necessary incentive for developing these mines whose ores were carrying from 20% to 60% copper and from $6 to $32 per ton in gold. 16]

In addition to this suggestion for a possible railroad connection to the Ubehebe, a proposal was made two years later that residents of the Owens Valley region unite in construction of a road across the Inyo Mountains to the borax, copper, and gold deposits of " the Saline Valley and Ubehebe regions. Another possibility mentioned in 1899 was that the Carson and Colorado Railway would eventually be extended into the Panamint Valley and tap the Ubehebe region along 'the way. Despite the prevailing lack of transportation facilities, however, development was proceeding in the 1890s on the one big copper mine in the Ubehebe, whose workings already included a seventy-five-foot tunnel and a thirty-seven-foot-deep, shaft with crosscut. Water had to be piped in from a nearby spring and the ore transported to the railroad over a rough wagon road, probably west through Saline Valley. [17]

b) Boston Capitalists Become Interested

Around the late 1890s and early 1900s many Boston capitalists became interested in the copper mines of the Ubehebe region and the adjacent Saline Valley, probably as a result of the record price for copper (19-1/4¢/lb.) reached in 1899. In that year a representative of certain Salt Lake City parties, after a detailed preliminary examination of the Ubehebe area, reported to his employers that the copper deposits in the Saline Valley region--primarily the Ubehebe, Sanger Group, and Hunter and Spear properties--appeared to be of sizable value. One of these capitalists, a Mr. Scheu, came to the area to inspect the property firsthand and took options on a great number of locations in the district. Subsequently all parties from whom options had been acquired were summoned to meet with Scheu and an S. H. Mackay and transfer the subject properties. The syndicate purchasing them was reportedly capitalized for $75 million, and intended to hire miners and begin development at once to determine the depth and extent of the ore bodies. A railroad connection was deemed essential for the success of. the venture. A 1,000-ton-per-day-capacity reduction plant was even anticipated if water could be found; otherwise the ore would be shipped to smelters. An initial sum of $5,000 was paid toward purchase of the Sanger Group, with other transactions to follow. The ultimate outcome of the whole venture, however, was that Scheu and Mackay embezzled some of the money due the Eastern backers, disgusting the Boston group to such a degree that they washed their hands of the whole enterprise. [18]

In 1901 George McConnell and his associates bonded a group of mining claims at Ubehebe to a Boston syndicate for $125,000. About a half dozen groups of claims here, in fact, were under bond, for amounts varying from $25,000 to $50,000, when a financial panic of sorts enveloped the Boston commodities market, and the deals were never concluded. Copper prices reached rock bottom in 1902, when only 11¢/lb. was offered. Due largely to this copper slump, in that year the approximately eighty copper, gold, and silver claims in the Ubehebe, located within a radius of about six miles of each other, were only touched by assessment work, though results were still encouraging. [19]

A description of the Ubehebe area in 1903 again mentions its inaccessibility, despite which regular assessment work on all the main ledges and deposits had been regularly performed for the past several years. One pleasing aspect of mining in the district was that the mountainous terrain permitted mining by drift tunnels rather than shafts and hoisting methods, which was much more economical and a great deal less time consuming. The mineral-bearing zone was reached by only one wagon road, stretching from the Inyo Mountain Range across Saline Valley, its primary drawback being the extreme heat encountered along its course during the summer months. Properties in the north end of Ubehebe were at this time producing ore assaying $12 to $18 in gold, carrying some silver, and ranging from 5% to 20% in copper. Ore in the middle sections carried 4% or 80 lbs. pure metal to the ton, while the southern section was mostly idle. Railroad access was still necessary for realization of the region's full potential, and it was remarked at this time that if the Los Angeles, Daggett and Salt Lake Railroad was constructed, a forty- or forty-five-mile spur could open up the whole Ubehebe to the world market. As had been stressed often before during discussions of possible routes into the area, the best way to spark the interest of Eastern mining capitalists was to be able to offer better ingress and egress routes than the rough trails currently in use. [20]

c) Rising Copper Prices Benefit Ubehebe

Starting about 1904 the price of copper and of shares of copper-producing companies began a slow but steady rise. By 1905 the Ubehebe copper district was industriously active, and several properties were producing: the Spear brothers and W. L. Hunter had made three ore shipments returning 26.24% copper, $8 in gold, and 3 ozs. of silver per ton from their Ulida property; R. G. Paddock and H.L. Wrinkle of Keeler were beginning development of thirty claims; and S. H. Reynolds owned a group of claims from which he was procuring a more than satisfactory showing. A new record price for copper of 19-3/4¢/lb. was reached in 1906, and future prospects appeared bright indeed. Several factors were responsible for this dramatic change in the market: an increase in the amount of copper needed for electrical conduction purposes, the escalation in the building of trolley lines, the electrification of steam railroads, and the pressing need for copper in China and throughout the Far East for recoinage use after the Russo-Japanese War.

Finally consumption had overtaken production and created a strong demand both here and abroad for immediate delivery:

At the price copper is selling at the present time, it is no wonder that the mammoth copper properties of Saline valley and the Ubehebe districts are claiming the attention of mining men from all parts of America. These properties are reported as carrying a very high percentage in copper, and the only reason and drawback that keeps them from ranking as the foremost- copper properties of America, is their isolated position, lack of water, and being owned by people who have not sufficient means to enable them to build plants and furnish cheap transportation facilities. Men of capital are sending their agents here to investigate, and in every instance they seem to be much impressed by the magnitude and high values of the properties. If copper continues to hold to nearly the high figure it has attained, we feel confident that in the near future, the mines will be in charge of people who have ample means to bring the product of these properties in touch with the market. [21]

One of the large mining transactions that took place at this time was the sale of the Sanger and Mairs copper-silver-gold properties to a New York businessman for a reported $200,000. Coincidental with the impetus to copper mining provided by the advance in prices was the rising enthusiasm for the metal among the desert community, and on the East Coast especially, generated by the discovery of rich lodes such as those at Greenwater that created a new town practically overnight. Some of that bonanza camp's most prominent backers, such as John Salsberry from Tonopah, Jack Gunn of Independence, and Arthur Kunze also sent prospectors into the Ubehebe area. [22]

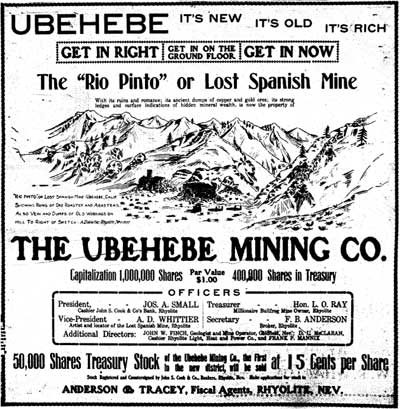

Almost instantaneously Ubehebe mining properties began to move. McConnell and associates again bonded some copper properties to a Salt Lake City firm; A. F. Mairs received a payment for his property adjacent to Saline Valley and also bonded seven claims to Goldfield people; a Salt Lake group was employing eight men on the Ulida Mine; a Mr. Whittier and associates discovered and filed on the Rio Pinto Group or Lost Spanish gold and silver mine north of Hunter's Ranch; the Guggenheim Smelter Company of the American Smelter Trust Company purchased forty of W. A. Sanger's claims, intending to erect a smelter twenty miles away in Deep Springs Valley; Goldfield people took a $100,000 option on a group of claims owned by John Miller, one of the pioneer locators in the area; and Senator Nixon and George Wingfield even acquired an interest in some area copper claims for $70,000. Except for six treacherous miles, a decent road now existed from Montana Station via Steininger's Ranch (later Scotty's Ranch near Grapevine Canyon), providing access to the region from Rhyolite and Greenwater. [23]

|

| Illustration 227. Advertisement for Lost Spanish Mine, Ubehebe Mining District. From Bullfrog Miner, 24 May 1907. |

d) Townsites are Discussed and a Mining District Formed

The spring of 1907 saw the systematic continuance of development in the Ubehebe area. Although as many as two townsites had been proposed, so far the only population centers were the small camps and groups of prospectors scattered here and there one-quarter to four miles apart from each other. Jack Salsberry, in the meantime, had bought Sanger's group of claims and was in the throes of trying to create a decent auto road from Montana Station to the site he had chosen for a town directly northwest of the Racetrack playa near the entrance to his mine property. This action probably contributed more than any other single factor to the influx of influential people into the area, not only from the neighboring towns of Salt Lake City and Rhyolite and Goldfield, but eventually from as far away as Boston and Philadelphia. Suddenly the desirable mining locations in the Ubehebe were accessible to all. "Mr. Lockhard says that you would almost think, from the people that are met in Ubehebe, that you were in the Bullfrog district," remarked one newspaper article. [24] The sixty-two-mile trail from Rhyolite was well traveled, and several large teams constantly moved over Salsberry's road to Bonnie Claire. A corps of surveyors from the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad were busy determining the most feasible route to the area, and four engineering outfits were already in the region surveying properties. Two townsites, Ubehebe and Saline (Salina) City, were reportedly being platted eight miles apart to house the population of fifty or so miners. Already a warehouse and corral had been erected at the latter site, and water would be piped in as soon as possible. The desire of the people in the area to form their own mining region separate from the Big Pine District was voiced in the spring at a meeting held in the Saline Valley salt works that culminated in formation of the Ubehebe Mining District. [25] Boundaries of the district, whose recorder's office was established at Saline City, were delineated thusly:

Commencing at Waucoba Peak, thence southerly along the summit of the Inyo range past Cerro Gordo Peak to Hunter Ranch trail, thence along Cottonwood creek to Lost Valley, thence northerly along the trail to Surveyors' Wells, thence northeasterly along Death Valley dry wash to northeast corner township 10 south, range 41 east, thence westerly on north line township 10 to Waucoba Peak. [26]

e) Ubehebe Copper Mines and Smelter Company Determines to Construct Railroad into Area

Several large properties were now operating in the Ubehebe: the Meyers; the Los Angeles Group; the Spears Group and Ulida; the Paddocks, Rooney, Wooden, and McConnell holdings; the Lakeview Group owned by Rhyolite people; the Joseph Cook (Crook) possessions, including the Wedding Stake; and the Valentine Group of fourteen claims. The newly-organized Ubehebe Mining Company, capitalized at one million shares, had bought the six Rio Pinto (Lost Spanish Mine) claims about ten miles from the new Saline City, plus the water right to Hunter's Springs. [27] The Sanger and Mairs properties, options on which were held by the Fitting Company, were some of the most notable claims in the district. Water was available several miles from the mines and was hauled in by wagon at $1 per barrel.

The largest and best-known mine in the Ubehebe area, as well as the most highly developed, was Jack Salsberry's property, operated by his newly-formed Ubehebe Copper Mines and Smelter Company, which opened offices in Baltimore to promote company stock in the large Eastern commercial centers. The mine was actively supported by a variety of Eastern capitalists who made several inspection tours to the area over Salsberry's recently completed road to Bonnie Claire. After one such jaunt the following comment was noted:

To many readers, Ubehebe is an unheard of camp, yet it is like many other sections in the state that are wonderfully rich in minerals but have not been brought especially to the attention of the people simply from the fact that those owning the properties are not looking for notoriety or endeavoring to boom their district. They are there to develop and mine their properties and secure substantial results to those interested in common with them and not for the purpose of advertising. [28]

Encouraged by the optimism and generosity of their supporters, Salsberry and Ray T. Baker, the two principals in the new company, conceived a plan of constructing a railroad to their mine from Bonnie Claire and of erecting a smelter there to reduce the ore before shipment. Persuading the prestigious banking and brokerage firm of Peard, Hill & Company of Baltimore, Maryland, to underwrite the bond issue for the project, work on a permanent survey of the proposed route was started with Salsberry receiving assurances that all bonds would be placed before 15 November and grading commenced shortly thereafter. The bonds were to be sold largely in Europe. It was planned that the forty-eight-mile-long standard-gauge track would head down Grapevine Canyon past the present site of Scotty's Castle, wind around Ubehebe Crater, and eventually reach Salsberry's mine near the 'northwest corner of the Ubehebe valley. The one million dollars worth of railroad bonds would be floated as a separate company to comply with the law, but in reality would belong to the Ubehebe Copper Mines and Smelter Company, thus greatly increasing its assets. The railroad would also haul ore for other mines in the area and thus hopefully soon become a regular dividend payer. Cost of the project was estimated at $800,000. In anticipation of the line's arrival, a well had already been sunk on Salsberry's new townsite to a depth of 155 feet, and as soon as water was reached, the site would be platted and the selling of lots would commence. [29]

Suggestions for opening up the area in another manner and from another direction included a proposed change in the Keeler-Skidoo wagon road route, bringing it through the Panamints further north at Townsend Pass and thus closer to northern mining properties. By fall 1907 the Kimball Bros.' Bullfrog Stage & Transfer Company started a regular weekly service to Ubehebe City, running the twenty-two miles to Grapevine the first day and the next forty miles on the second day. Corrals and buildings for the stage company were in process of erection at Bonnie Claire and Ubehebe, and stations were being established along the route. The stage leaving Ubehebe on Wednesday would arrive at Bonnie Claire in time to meet the Clark trains from Bullfrog and Goldfield. Four horses were to be used on the road, whose condition was described as "very bad." [30] Two survey crews were busy preparing townsite maps. Twenty tents were already on the ground, as were two saloons and a grocery store. Application for a post office was forwarded to Washington. Having failed in the well project, plans were being made to pipe water in from nearby springs. [31] Meanwhile Salsberry was sinking wells at various points along the Ubehebe wagon road for use by the big freight teams passing back and forth between Bonnie Claire and Ubehebe. He was also. buying coal lands in southern Utah and taking options on others to provide coke for the smelter he proposed. to erect near his Ubehebe Mine. [32]

f) Work Continues Despite Panic of 1907

The influx of Eastern and European visitors and investors to the area continued over the next several months, despite the hard times and depression leading up to the Panic of 1907. Although copper mining was still very strong in spite of the slump, a prophetic opinion was voiced at this time by a certain veteran desert prospector, Jim Titus, who ventured the observation that

It is the prevailing opinion that the predominant metal in the district is copper, and while some fine copper ore has been discovered on the surface, I think it will be found with deeper exploration, that gold, silver and lead will be the leading values. [33]

Properties in the area were being worked despite the tight money situation, with a force of about twenty-five men hoping to hold on until the financial situation across the country eased. In November Salsberry was reportedly working seventeen men on his company's claims, and expected to increase the force upon the arrival of new machinery. Several other companies in the area also were employing good-sized forces on annual assessment work. The townsite, meanwhile, was undergoing a construction spurt; water was being hauled in barrels from springs six miles away. Salsberry and some Rhyolite associates were also operating the Ubehebe Lead Mining Company, Ubehebe Sunset Copper Company, and the Ubehebe Contact Company, comprising a total of forty claims in the district. An Inyo Copper Company also existed. [34]

|

| Illustration 228. Ubehebe Mining District, 1908. |

The bubbling optimism centering around the proposed Bonnie Claire & Ubehebe Railroad continued, although initial construction was still in abeyance until all bonds were sold. Despite the money-market depression that had delayed the start of development, it was promised that the route would be in operation before mid-summer of 1908. Arrangements were still reportedly being made to erect a fine hotel and several residences and business houses at the terminus of the line at Saline City. Salsberry never saw fulfillment of his dream, however, for the closing of banks and consequent termination of a ready money supply scuttled the project entirely. Although a camp of Saline evidently did exist for a short while, it never became the prosperous railhead and mining center envisioned by its founder.

g) Mining in Ubehebe Hampered by Isolation and Transportation Problems

A 1908 report on California's copper resources lists several claims as still active in the area (note that the western boundary of the Ubehebe Mining District was somewhat nebulous, extending west across the Saline Valley toward the east slope of the Inyo Mountains):

Valentine Group--fourteen claims halfway between Keeler and Ubehebe. Owned by I. Anthony and D. Pobst of Lone Pine.

Navajo Chief Claim--one-quarter mile south of Dodd (Dodd's) Spring. Owned by W. T. Grant of Olancha and George McConnell of Independence.

Eureka Claim--One-eighth of a mile south of Dodd Spring. Contained 80-foot shaft and 100 feet of drifts. Owned by Jacob Stininger [sic] of Tule Canyon. Originally discovered in 1880s.

Trail Claim--at Dodd's Springs. Owned by W. T. Grant and George McConnell.

Dodd's Springs Claim--on same ledge as Trail Claim. Owned by Grant and McConnell.

Ulida Group--eight prospects in Dutton Range. Owned by Spear Bros. and William L. Hunter of Lone Pine. Adjoined by Keeler, Olancha, and Spear claims on northeast.

Copper Knife--one-quarter mile east of Racetrack. Owned by Grant and McConnell.

Anton & Pobst Claims--five claims sixteen miles east of Keeler, with twenty-foot tunnel. Owned by John Anton and David Pobst of Lone Pine.

Silver Hill--seven miles east of Independence. Owned by J. C. Roeper of Independence.

Green Monster--continuation of Silver Hill prospect, with 300-foot tunnel and two crosscuts. Owned by D. C. Riddell of Gilroy, Ca.

Copper Tail--adjoined Green Monster. Owned by Roeper.

Copper Point--one mile northeast of Green Monster. Owned by Max Fausel.

Inyo Copper Mines and Smelter Co.--owner of nineteen claims at southern extremity of Ubehebe Mountain. Camp was on old Ubehebe trail and workings one-half mile east of Bonanza property. Claims on which the most work had been pushed so far were the Excelsior, Fairbury, Fairbanks No. 4, Ormonde, Ormonde No. 2, Kenilworth No. 1, Kenilworth No. 2, Pluton and Ajax (Alta). R. G. Paddock of Keeler was managing the work. (Evidently this company's development did not ultimately amount to much.)

At the northern end of Ubehebe Mountain were the older claims on which work had just recently resumed. The Sanger Group controlled by John Salsberry, consisted of the Tip Top; Star, at the base of Ubehebe Mountain; Copper King one mile west of the Star and owned by W. A. Sanger of Big Pine; Prince Group four claims also owned by Sanger & Son; Bluejay, on the east side of Saline Valley and owned by A. Mairs of Independence (its only recorded production was in 1915 when Mairs shipped copper and silver ore); Red Bird owned by F. A. Mears of Big Pine; and the Good Luck Group owned by R. Lockhardt & Penrod of Rhyolite.

In the southern part of the Ubehebe Mountains were the Wedding Stake and Red Bear claims, owned by J. H. Crook and Sam Baysdon of Keeler. Other properties in the region were the Roberts & Derat and Woodin & McConnell claims the Lake View Group of eight claims one-half mile from the Lost Burro and under the same ownership, carrying gold and copper and located on the east slope of Tin Mountain, owned by W. D. Blackman of Rhyolite and associates; and the Scott Group of twelve claims near Dodd Spring, carrying gold, silver, lead, and copper, and owned by W. Scott and Mr. Titus. [35]

Despite the fact that improved machinery was facilitating mining operations in the early 1900s and that the high prices being paid for copper enabled the expenditure of more money in the search for it, the miners of the Ubehebe region were still hampered by several deficiencies: no ready water supply existed near many of the mines, which had to obtain water either from Dodds or Grapevine springs or from a new well on Tin Mountain; access was still difficult, the auto road to Bonnie Claire being the only decent route other than a thirty-five-mile trail to Keeler and Darwin and a long, hot wagon route from Alvord; and no smelter had yet been built in the area. As a consequence, tons of ore had to be stockpiled on the dumps to await cheaper transportation, the wagon haul making mining of any but the best-grade ore highly impracticable. Despite the problems, extensive development continued through the winter of 1907, into early 1908, with the Watterson-Smith lead and silver mine, considered the biggest undeveloped property of its kind in California, promising so well that two loads of provisions were hauled in to support a complete summer campaign. Another Ubehebe Mining Company was incorporated in Bishop, California, with W.W. Patterson.

Other properties that might have been included in the Sanger Group were the later Copper Queen No. 1, one-half mile north-northwest of Ubehebe Peak, the Copper Queen and Copper Queen No. 2, and the Bonanza (I-lessen Clipper) filed on by George Lippincott, Jr., in 1951 and located on the road between Racetrack Valley and Saline Valley about 2 miles from its junction with the road to the Lippincott Mine. According to McAllister the old Ubehebe pack-train trail from Owens Valley crossed the Bonanza property before intersecting the Racetrack Valley road to Bonnie Claire. Special Report 42, pp. 47-48. This report should definitely be studied for detailed information on other mines in the Ubehebe area (Watterson?) of Bishop as a principal in this company that owned 5 claims in the Ubehebe area. [36]

Plans were still being formulated for a railroad connection with the area, the fact that none ever succeeded certainly not being due to a lack of effort on anyone's part. By the fall of 1908 the vast reduction works at Ely, Nevada, were in need of large quantities of lead ores for fluxing purposes, and it was suggested that this problem could be solved by projecting an Ely & Goldfield Railroad, financed by F. M. "Borax" Smith, C. B. Zabriskie, and others, to Goldfield and then southwest down the valley between the Magruder and Slate ranges, swinging around Tin Mountain and passing down its west slope into the Ubehebe region. Another plan four months later to open up the immense bodies of low-grade rock that could not be profitably shipped by wagon was to outline a route from Cuprite, north of Death Valley, through Lida to Silverpeak, with an extension of the line running into Ubehebe. [37]

None of these tentative propositions ever bore fruit, however, and the declining price of copper and lack of investment capital in the first decade of the twentieth century, in addition to the need for improved transportation facilities, precluded any extensive, large-scale development work in the area, although a large number of promising prospects were being systematically checked. Arlie Mairs, operator, of the Blue Jay copper claims only twelve miles from the loading terminus of the thirteen-mile-long Saline Valley salt tramway, was solving his transportation problems by 1914 by shipping his ore via that contrivance. W. W. Watterson and Archie Farrington, operating the Ubehebe Mine, approached the problem from a different angle. Realizing that the transportation of ore by animal power would never be economically profitable, they decided to employ a ball-tread auto tractor provided by the Yuba Construction Company of Marysville for four trial trips at company expense. The distillate-burning engine would haul ore wagons loaded as trailers over the fifty miles to the Tonopah & Tidewater station at Bonnie Claire in a four-day round trip.

Such a tractor was envisioned as being more economical than trucks for hauling large amounts of ore because the latter required a separate truck and driver for each load and because often unloading over bad stretches or unusually high grades was necessary. The tractor, on the other hand, could haul loaded wagons over these difficult stretches one at a time with no unloading. It carried no load on its own wheels except the engine and a driver, making the Caterpillar-type machine so lightweight that it could be turned in a narrow road at sharper angles than trucks, which were often too top-heavy and unsafe on narrow roads with hard grades. [38]

h) Variety of Metals and Nonmetals Contribute to Ubehebe's Production Record

By 1916 several silver claims in the vicinity were still being worked, but tungsten strikes were also being made, having been first discovered on the dumps of old copper prospects. Most of these were located south of the Racetrack in the area of Dodd and Goldbelt springs. Because of low prices for this commodity around 1920, the tungsten mines were shut down,. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s the Ubehebe Mine was one of the most active mining operations, with part of it, the Butte Claim, being a principal lead producer in 1930. [39]

Recent copper activity in the region has occurred only at the Sally Ann Mine near the playa, but no production resulted. The principal metallic deposits in the area are the lead-silver-zinc properties stretching from the Ubehebe Mine in the northern section to the Shirley Ann Mine near Big Dodd Spring. Nonmetallic occurrences include, besides asbestos, four talc lodes (Homestake, Quackenbush, Keeler, and Ubehebe) whose reserves are thought to be substantial but whose productivity is limited by their remoteness.

Miners and prospectors were first attracted to the Ubehebe area in the late 1800s by the presence of copper ore, but it soon became evident that the isolation of the deposits made them almost impossible to work profitably. Exact figures on early production of the metal are difficult to determine because of the scanty and nebulous descriptions of these first properties. Many small mines probably kept no systematic records because they maintained no steady production. Because the only road adequate for shipping ore from the Ubehebe led to the railroad at Bonnie Claire, Nevada, most material went there, where it was often combined with Nevada ores, a practice tending to cloud the Ubehebe's actual production record. Also hampering the determination of productivity from each site was the tendency of early shippers to neglect to state the individual sources of the ore they moved. The first actual recorded production from the area was from the Ubehebe Mine, which shipped 491 ozs. of silver in 1908. From that year up to 1951 the metallic content of 4,788 tons of ore mined from the Ubehebe Peak area could be broken down as follows: 332 ozs. gold; 44,729 ozs. silver; 120,180 lbs. copper; 2,657,559 lbs. lead; 164,959 lbs. zinc. Annual lead production from the region has been less than 145,000 lbs. The annual copper production since 1930 has been under 1,000 lbs., while silver production usually did not exceed 3,700 ozs. a year. Gold has been recovered almost entirely from the Lost Burro Mine. The record for longest productivity in the area is held by the Ubehebe Mine, although it experienced a quiet period between 1931 and 1946, while the Lippincott Lead. Mine. has undergone the most continuous mining in recent years, from 1938 to 1952. [40]

i) Other Ubehebe Properties

The following is a list of a few other Ubehebe area properties not specifically mentioned earlier. This list is by no means a complete summary of all mining activity in the area:

Red Bell Group--four claims owned by Charles del Bondio and associates in the vicinity of the Racetrack playa. Bullfrog Miner, 15 June 1907.

B & B Group--gold and copper claims in the Goldbelt Spring section, owned by Len P. McGarry and Rhyolite associates. Bullfrog Miner, 14 September 1907.

Big Gun Mine--near Racetrack, owned by George McConnell. Inyo Independent, 29 November 1907.

Emerald Group--copper and lead claims near Wedding Stake, owned by J. P. Hughes. Bullfrog Miner, 1 February 1908.

Randolph--four miles from Lost Burro Mine and adjoining Racetrack, owned by McConnell, Dr. Woodin, and W. Grant. Bullfrog Miner, 20 February 1909.

Raven Mine--lead and silver property five miles north of Dodd Spring, owned by J. Crook and A. Farrington. Idle in 1926. Eakle et al., Mines and Mineral Resources p. 102; Journal of Mines and Geology 22 (October 1926):496.

Alvord Group--tungsten claims five miles west of. Goldbelt Spring. Located by William Elliot and Ray and Ross Spear of Lone Pine in 1916. No production and little development. Eakle et al., Mines and Mineral Resources p. 127; Journal of Mines and Geology 37 (April 1941):310.

Monarch Mine--tungsten claim between Dodd Spring and Goldbelt Spring, located in 1915 by Monarch Tungsten Co. of Denver. Eakle et al., Mines and Mineral Resources p. 127.

Butte Group--six claims midway between the Racetrack and Dodd Spring. Assessment work only. Owned by R.C. Spear, E.L. Spear, and Hunter of Lone Pine. Eakle et al., Mines and Mineral Resources p. 67.

Settle Up Group--five miles north of Dodd Spring, idle in 1926. Report 22 of the State Mineralogist 22 (October 1926).

Sally Ann Mine--copper mine on west slope of range east of Racetrack playa. Five lode claims owned by James Arnold, Orval Huffman, and Sally Ann Smith of Compton, Ca. Worked late 1947 to mid-1948. Copper deposit, known in 1905 and as early as 1902 when referred to as Copper Knife Mine. Mine camp consisted of cabin and two tent frames at edge of playa. Journal of Mines and Geology 47 (January 1951):37; McAllister, Special Report 42, pp. 46-47.

Blue Boy Group--six unpatented lode claims within 1/2 mile of east side of Racetrack on steep slope. Probably dates from around turn of century. Slight development. Walter Gould, "Mineral Report for the Blue Boy, Blue Boy #1, Blue Boy #2, Blue Boy No. 3, Copper King, and Homestake Lode Mining Claims in Death Valley National Monument, California, 13 June 1978," p. 1.

Homestake--about one to two miles south of Racetrack on road to Lippinott Lead Mine. Located 1934. Staked for talc. Gould, "Mineral Report," pp. 1, 3.

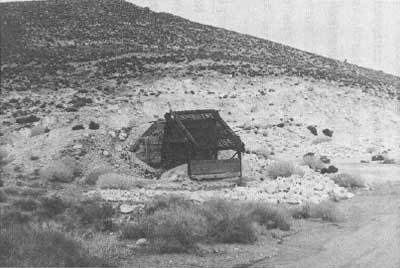

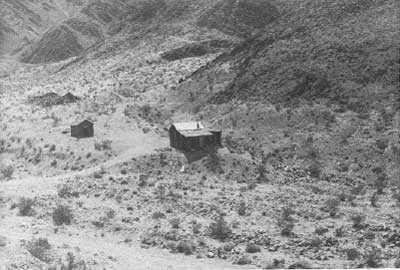

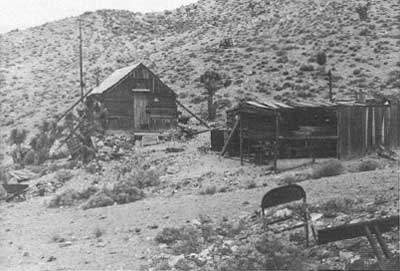

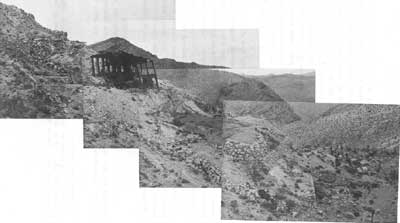

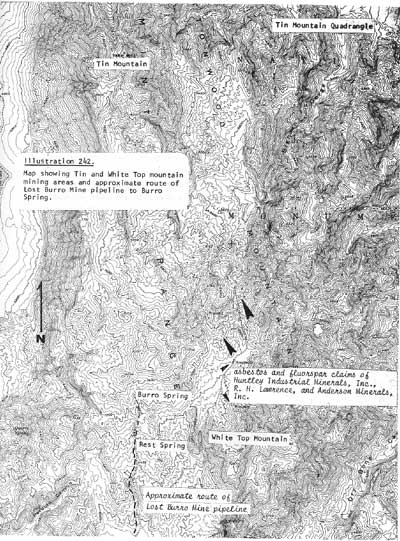

Tin Mountain and White Top Mountain--some copper prospecting activity was taking place on Tin Mtn. by 1908 on the property of John Miller, one of the early locators in the district. In the 1940s Huntley Industrial Mineral, Inc., owned asbestos property about three miles south of Tin Mountain in the general area of the prospects shown just northeast of Burro Spring on the Tin Mountain USGS quad. In the early 1960s roads had been bulldozed to several non-producing mines in the area worked by weekend prospectors. Anderson Minerals, Inc., at that time claimed placer locations in the Tin Mountain area and near Burro Spring and was intending to develop fluorspar. The Lawrence Asbestos and Fluorspar claims located on the north slope of White Top Mountain two miles northeast of Burro Spring have been explored by several lessees over the years, but have produced only a few hundred tons of asbestos and fluorspar. Much scarring in the area has resulted from dozer prospecting and road building. The property consisted of three fluorspar claims, thirty-two asbestos claims, and a millsite under, location by R.H. Lawrence of Mojave. In 1970s the lessees proposed to develop the fluorspar deposits and ship the ore to Barstow via truck. Today the area consists of bulldozed prospects and a miner's shack. Wright H. Huntley, pres., Huntley Industrial Minerals, Inc., to T.R. Goodwin, Supt., DEVA NM, 27 July 1949; District Ranger, Grapevine, to Chief Ranger and Supt., DEVA NM, 15 October 1963; Supt., DEVA NM, to Dir., WRO, 1 April 1971; LCS Survey by Henry Law and Bill Tweed, 3 December 1975.

|

| Illustration 229. Miner's cabin in White Top Mountain area. Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

|

| Illustration 230. Tin Mountain mining area. Photo courtesy of G. William Fiero, UNLV, 1973. |

Ubehebe Peak--M.S.&W. Inc., of Bishop located Jarosite lode mining group of 111 claims on west slope of peak in late 1960s or early 1970s. Samples taken reportedly showed high copper and molybdenum values. It was intended to diamond drill the property. Supt., DEVA NM, to Dir., WRO, 1 April 1971

j) Sites

(1) Ulida Mine and Ulida Flat Site

(a) History

Whether or not the Ulida Mine, situated in the Dutton Range about three miles north of Hunter Mountain, is the site of W.L. Hunter's original discovery that opened up the Ubehebe area to mining has not been conclusively determined by this writer. McAllister maintains that it is, and places the mine's discovery date at 1875 or before. According to observations made by Lt. Rogers Birnie, Jr., during his 1875 survey of the Death Valley region, eight locations had been filed in the Ubehebe area by Hunter in that year, and whether by coincidence or not the Ulida Group did initially encompass eight prospects: the Ulida, Sorbia, Sardine, H.M. Stanley, Kabba Riga, Virginia, Maryland, and Hunter. A 1906 notice states that the Hunter & Spear Mines "were the first found [in the Ubehebe area] and are comparatively the best developed. A later 1907 article, however, stated the property had been located only twenty-five years earlier. [42]

In partnership with the Spear brothers by 1902, Hunter had opened up the large outcroppings on the property, which also yielded gold and silver, by means of two 150-foot-long tunnels, one above the other, and had accomplished some minor stoping. Around 400 tons of ore were recovered, hand sorted, and packed on mules the seven or so miles to the Keeler wagon road over which they were hauled to town and then shipped to the smelter. The Spearses are reported to have shipped out sixty tons of ore returning gold and copper values of $600 a ton. [43] Upon Hunter's death in 1902, Reuben Cook Spear acquired the property.

The mine evidently remained idle for the next four years or so, its remoteness making it unprofitable to work. Then a Salt Lake City group, composed of Samuel A. King, Alfred Mikesell, Raymond Ray, and a Mr. Dalton of New York, rediscovered it and procured an option on twenty-one claims. Ore with a high gold and silver showing as well as substantial copper values was developed. [44] Ray and Mikesell subsequently turned their option over to the firm of King (Judge William H.), Burton, and King (Samuel A.?), who in 1907 sold the mine for a cash consideration in the neighborhood of $45,000 to $55,000 plus a sizable amount of stock shares in the Ulida Copper Company, incorporated for $5,000,000 by New York and Salt Lake City capitalists. The mine assets now consisted of a seven-foot vein of ore averaging 14% copper and from $3 to $10 in gold. Much iron was present in the ore, making it ideal for smelting. [45]

In April 1907 the Ulida was described as the "queen bee of the camp [Ubehebe}," [46] the property's development now being guided by the Ulida Copper Company, which immediately applied for 100 inches of water from Hunter Ranch Creek to be diverted to their property in the Ubehebe Mining District by gravity force. [47] In June development work at the mine was proceeding so satisfactorily that a sign was said to be hanging out on the property advertising "Forty Men Wanted." The adjoining Los Angeles Copper Group had also been incorporated into the company's holdings and was opened up at this time. [48]

For the next few months a large force of men kept busy performing assessment work and it was intended to keep at least five men working in the tunnel all winter. At a distance of about 250 feet in, a great strike in a blind lead was encountered, producing ore samples running 35% copper and $100 in gold. By March 1908 the strike on the Ulida ledge was reported as carrying values up to 60% copper, $14 in gold, and over 200 ozs. in silver to the ton. [49] Work was continuing to crosscut the vein and drift with it to the main contact.

In the summer of 1908 one of the groups visiting the Ubehebe area over the new Bonnie Claire road was a party consisting of Robert Wood, a London mining expert for the Ulida Copper Company; J.N. Dalton of Boston, president of the company; Samuel A. King of Salt Lake City, a company director; and R. C. Spear of Lone Pine. The company had incurred some indebtedness that it was now paying off, and under the supervision of a new local manager the development work was expected to become more extensive in a short while. Over six thousand dollars had already been expended in the mine by the company, which was sure this would evolve into one of the West's great copper properties. [50]

In 1912 Reuben Spear and his son Bev worked some outcroppings a few miles above the Ulida tunnel, hauling the ore by muleback the few miles to the wagon road to Keêler. In 1916 notice was printed of the discovery of tungsten by the Spear brothers on their Ubehebe copper property. Whether this refers to the Ulida Mine is not known. From here on, information on the property is scanty. P.E. Day and Cliff Palmer relocated the Ulida as the Morning Star Mine in 1935, and four years later W.G. Walker filed on it as the Walker Mine. From 1947 to 1949 Edna Horstmeier kept up assessment work on the claim. [51]

(b) Present Status

i) Ulida Flat Site

A very faint set of tracks leads from the Hidden Valley road west across Ulida Flat to the range of hills bordering its western edge. Here, near the mouth of the narrow gulley leading up to the Ulida Mine, are low stone foundation walls built into the hillside. They support leveled platform areas on which tents were probably erected. Several tin cans and 1-1/2-inch-diameter metal rods litter the site, on which purple (light and dark) glass can be found. Also seen were dark brown bottle fragments and parts of a typical turn-of-the-century light-blue glass medicine bottle.

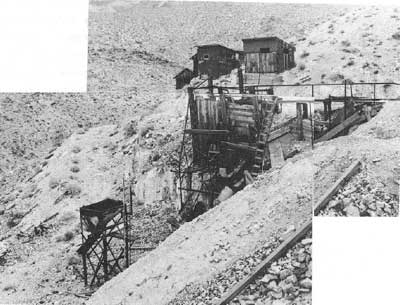

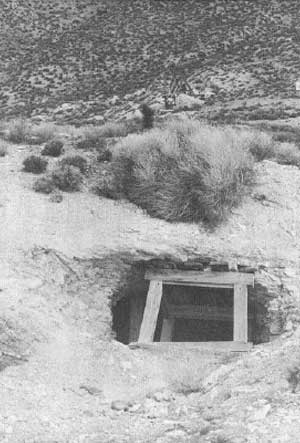

ii) Ulida Mine

The mine adits are located at the top of the gully directly above the Ulida Flat Site at an elevation of about 5,600 feet and are reached by a steep and rugged 1/2-mile burro trail. Tumbling down the ravine in the immediate vicinity of the mine are rusty tin cans of assorted sizes. The workings consist of a main adit entrance with nearby waste dump, and another caved-in adit with dump on the hillside immediately above. The main adit entrance is particularly striking because the rock face around the wooden entrance door is a vivid greenish-blue color, while the piles of ore stacked up near the entrance are of this same brilliant hue. In front of the door and north of the tram tracks is a shallow vertical shaft only about twenty feet deep. Assessment notices are bolted to the adit entrance door.

|

| Illustration 231. Ulida Flat Site, to northwest. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 232. 00 Main adit entrance, Ulida Mine. Vertical shaft to right near posts. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 233. Larger of two stone smelters at Ulida Mine. |

Immediately downhill from the mine are three stone items: furthest east are the ruins of what appears to be a large, elliptical-shaped oven or smelter, about nine feet in diameter and with remaining rock walls about 4-1/2 feet high. Forty feet west of this toward the mine and at the base of the main waste dump is another smaller structure of the same type, only about five feet in diameter. This also appears to be a smelter operation. Between these two structures is a stone forge 3 feet high and 3-1/2 feet long. A small burro shoe was found on one of its edges.

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

i) Ulida Flat Site

it is this writer's belief that the Ulida Flat tent site was probably inhabited by miners working the Ulida Mine and possibly others in the vicinity that adjoined the Ulida holdings. According to newspaper articles of the early 1900s several people were working in the area on the same lead, the Ulida vein being very clearly defined for a distance of at least three miles. The site appears to be large enough to hold about three tents. It will be incorporated into the Ulida Mine National Register nomination.

ii) Ulida Mine

The Ulida Mine, one of the oldest mines in the vicinity, was one of the early claims, if not the first, filed on by Hunter and one whose development, along with that of other properties in the district, eventually resulted in formation of the Ubehebe Mining District. For this reason and because of the presence of two early stone smelters on the site and an associated tent camp nearby, this property is considered eligible for inclusion on the National Register as being of local significance.

(2) Goldbelt (Gold Belt Spring and Mining District)

(a) History

First occupants of the Goldbelt Spring area were probably Saline Valley Panamint Indians, one seven-member family reportedly appropriating the site as a winter village despite its relatively high elevation. [52] The initial mineral discovery that precipitated a small rush to the neighborhood was that of free gold made by Shorty Harris in the closing months of 1904. Utilizing the same route followed into the Ubehebe region--via Willow Spring to Surveyor's Well and then up Cottonwood Canyon--eager prospectors staked the first locations on the northeast slope of Hunter Mountain. Access to the area could also be gained over a forty-mile trail from Keeler via Lee Landing (Lee Pump), skirting Hunter's Ranch, and then heading northeast to the new camp. Harris, L.P. McGarry, E.G. Padgett (Pegot or Paggett), Joseph Simpson, and W.D. Frey were credited with the first strikes.

Development of the area started immediately and culminated the following January in establishment of the Gold Belt Mining District, with A.V. Carpenter as recorder, and embracing the territory stretching from the Ubehebe District on the west eastward to the north arm of Death Valley and from Tin Mountain south to Cottonwood Canyon. Ledges averaging four feet in width and containing a high grade of free-milling ore in addition to copper stains were the source of this perceived wealth. Samples taken to town returned assays of $8 to $176 in gold, plus smaller silver values. The presence of fuel and water in abundance was considered extremely conducive to mining operations. One early location °was referred to as the Gold Nugget Group, assaying from $38 to $240 in gold, but neither this nor any of the other reported seventy claims in the district received any extensive development work at this time. Nonetheless plans for a townsite were already forging ahead. [53]

In February 1905 it was stated that sufficient capital had been secured to thoroughly explore the district, this support probably having been obtained from the San Francisco parties who bonded the Goldbelt mines about that time. [54] No information has been found relative to the ultimate extent of the Gold Belt Mining District camp, nor has its exact location been determined. By 1905 the camp was described as abandoned, the only work in the area having been performed on thin veins and lenses. [55]

Despite the obvious slackening of mining activity in the Goldbelt area, a few of the original locators stuck fast to their claims, confident that a great future yet lay ahead if the extreme hardships imposed by lack of transportation facilities and insufficient working capital could be overcome. Len P. McGarry, for one, 'general manager of the Bullfrog West Extension, continued assessment work on his claims, which were showing gold values of $10 to $150 and as high as 36% copper content, at least through 1910. [56] Only a scattering of notices for new claims in the vicinity exist for the next few years. Most information concerns the B & B Group, about ten miles south of Salsberrys camp, and owned by McGarry, some Rhyolite associates, and W.S. Ball, B.T. Godfrey, and H.W. Eichbaum. These men were also interested together in twenty-four other locations in the area, mostly situated about twelve miles southeast of Salsberry's headquarters. In 1907 the B & B contained a shaft and an approximately 200-foot-long crosscut tunnel intended to reach the main ledge, which showed assays from $6 to $622 at a depth of 18 feet. Another promising group was the Snowbound, carrying 12% copper values. [57] At the start of 1910 the B & B had been developed with a 280-foot tunnel and was still achieving high gold assays of $620. The Snowbound was also receiving annual assessment work, the two properties now owned by Annetta Rittenhouse of Los Angeles, H.W. Eichbaum of Venice, L.P. McGarry of Pioneer, and W.S. Ball of Rhyolite. [58]

A revival of sorts hit the area around 1916 with the commencement of tungsten mining encouraged by its acceleration in price at the outbreak of World War I. Again it was Shorty Harris who first found the ore near Marble Canyon, about one mile southeast of Goldbelt Spring, shipping out a few hundred pounds worth about $1,500 in early March. Subsequent locations were centered in the region south of the Racetrack near Dodd and Goldbelt springs. Keeler was the closest shipping point, but though the route from Keeler to Lee Pump was now fit for auto traffic, only a trail still led from there to the mine locations. [59] In 1941 the Shorty Harris Tungsten Mine, composed of two claims three miles south of Goldbelt Spring and ten miles east of Dodd Spring, was owned by Bert Hunter of Olancha and E.G. Mason of Los Angeles. The only other data found on this gold and tungsten property concerns its purchase by William C. Thompson of San. Fernando, California, who also owned the Saddle Rock. Group near Skidoo and the Lost Burro Mine in the Ubehebe. New access roads had by now opened up the previously untapped property, and new machinery had been purchased for its immediate exploitation. [60] Either no production or only a very small amount resulted from these efforts in open cuts and a twenty-foot adit.

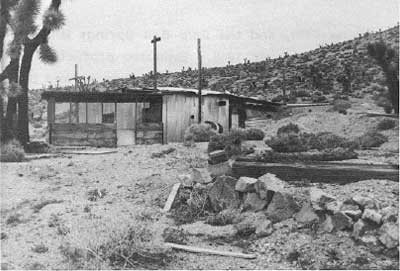

From the 1940s through the 1960s various small talc and other mineral operations existed in the Goldbelt area, but they were only sporadically active. The closest talc property whose workers might have resided at the camp site near the spring is the Quackenbush, but it is also possible that operators of the Calmet #1 through #27 wollastonite claims, about one-half mile northwest of the spring and owned by U.S. Minerals, occupied some of the cabins. This latter operation was envisioned as eventually developing into an open pit operation. Its thirty-one unpatented claims were located from 1959 on, and the #1 to #23. claims were worked as late as 1976 by Joe Ostrenger of San Fernando. In the 1960s the Goldbelt Spring camp was under lease to Sierra Talc, a company involved in exploration and development of several old claims in the surrounding area. (According to Belden, Mines of Death Valley, p. 65, Goldbelt Spring was an active mining camp in the 1960s.) The mill site was later obtained by William B. Grantham who quitclaimed it to Victor Materials Company, the present claimant.

|

| Illustration 234. Milk cow in garden of Goldbelt Spring community. 1959. Photo by Wm. C. Bullard and Dan Farrel, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

| Illustration 235. View of Goldbelt Spring community, looking southwesterly. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

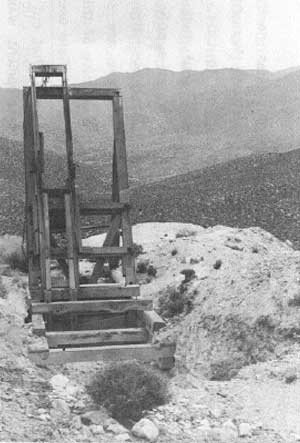

| Illustration 236. Loading or sorting structure, Calmet Mine. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

(b) Present Status

Goldbelt Spring is located about 4-1/2 airline miles northeast of Hunter Mountain at the head of Marble Canyon, the northern branch of Cottonwood Canyon. The presence of this valuable water source and its rather sheltered location made the site a natural spot for a small settlement. Today the ruins of what was once a moderately extensive mining community rest in the gully running from the spring to Marble Canyon. From their architectural style (or lack thereof) and meager furnishings, the three extant houses appear to date from no earlier than the 1930s or 1940s and probably have been occupied by talc miners, although no record of who actually built them has been found. One structure has already collapsed and another one burned. A root cellar and privy are also on site. Up toward the spring, to the southwest, is a small complex of fencing and corrals and a metal water tank. The spring, surrounded by a grove of rose bushes, lies about JOO feet above the bottom of the wash and is currently being utilized by the National Park Service as a burro trap.

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

No evidence of an early 1900s mining camp was found on the Goldbelt Spring site, the houses there now appearing to be of a later construction date. Because the 1905 Gold Belt Mining District saw little actual production or development, it is doubtful that permanent structures such as these were built at that time. The few talc camps existing within Death Valley National Monument will take on added importance as their numbers dwindle. Never constructed with long-term habitation in mind, their plywood walls and composition paper roofs fall easy victim to vandalism, fire, and natural weathering. The Ibex Hills talc mines in the southern part of the valley, in contrast to those in the Goldbelt area, possess greater production records, documented histories, and more physical remains of educational and interpretive value on site. For these reasons, the residential areas associated with them, such as the extensive one at Ibex Spring, are important also and should be accorded treatment of benign neglect.

Despite a lack of detailed information on both the Gold Belt Mining District and the Goldbelt Spring mining camp, it is recommended by the writer that the latter merits preservation as a representative type-specimen of a talc camp, displaying sufficient integrity of location, setting, and materials to provide an accurate portrayal, of the types of structures and methods of construction typical of communities occupied by talc miners in the Death Valley region during the 1940s through the 1960s. Reconstruction attempts at the Goldbelt Spring site are not advisable for several reasons:

1. the history of the site as far as is known does not warrant such an expenditure of time and money;

2. no photographs have been found showing the community's original appearance;

3. adequate supervision could not be maintained over the restored area; and,

4. the site's remoteness and consequent low visitation rate do not justify the expenses involved.

It is recommended by this writer that the Goldbelt Spring camp be preserved and efforts made periodically to arrest deterioration of the remaining structures. For those visitors who venture into this secluded corner of the monument, it is an eye-opening experience to suddenly discover this small community nestled in a lonely wash in the middle of such solitude. Under these conditions it is impossible not to attempt to visualize what life would have been like here and what sacrifices were made by those talc miners and their families who lived here in such isolation during comparatively modern times.

(3) Ubehebe Mine

(a) History

The Ubehebe Lead Mine actually began operations as a copper property, but its activities were somewhat overshadowed in the early newspaper accounts of mining in the area by those on the immensely wealthy and highly publicized copper properties of Jack Salsberry that lay nearby. The Butte Nos. 6-10 and West Extension Butte No. 3 were actually located in late 1906 through 1908, while the nearby Copper Bell Claim Group was not officially recorded until the late 1920s and early 1940s. Initial accounts of the property did not begin to appear until around the fall of 1907 when it was mentioned that "Messrs. Smith and Watterson of the Inyo County bank [Bishop] have sent in supplies and are about to begin operations on an extensive scale. [61]

In the course of pursuing annual assessment work on their claims, located one mile northwest of the new town of "Ubehebe," one of the owners picked up quite by chance a large rock sample that proved to be galena; further investigation- uncovered a four-foot solid ledge of this ore. Immediately the efforts of the eight men employed on the property were divided, four being put to work on the copper veins and four on development of the new galena ledge. During the assessment work, forty tons of lead ore were removed, running about $60 in silver per ton, a strike momentarily topping Salsberry's mineral showings. [62]

The Watterson stope was the first of five ore bodies opened up on the property, sometime after 1906, ultimately producing 700 to 800 tons of high-grade ore that was shipped to smelters. By February 1908 the eight-foot solid vein of lead was perceived to run entirely through the mountain, and was accordingly being opened up with drifts on both the Saline and Racetrack valley sides, making this one of the biggest and most-promising lead prospects in the district. Already over 250 tons of ore were on the dumps awaiting shipment. [63]

In March 1908 Archibald Farrington bought a one-third interest in the property for $6,000, while the other two partners, Smith and Watterson, were considering plans for construction of a road across the mountain range from the west to enable hauling of ore from the mine and salt from the Saline Valley deposits to Bonnie Claire. The new partnership incorporated as the Ubehebe Lead Mines Company, whose development work at the mine so far consisted primarily of one twenty-five-foot tunnel, all in ore, with a face showing of 70% lead and a high silver content. Two shifts were removing ten tons a day that were then teamed to the railhead at Bonnie Claire. [64]

A summer-long campaign on the property was planned, and in preparation for the isolated stay, two teams hauled 26,000 pounds of grain, groceries, and mining supplies to the site to sustain the crew during the long months ahead. A contract was also let at this time for hauling the ore recovered during the winter to the railroad at Bonnie Claire. In July it was reported that Watterson and his associates had organized the Ubehebe Mining Company to operate a group of 5-1/2 claims on which a tunnel had been excavated extending fifty feet and from which 1,000 tons of shipping ore were now available. [65] A month later the property was described as "easily the biggest undeveloped property of the kind in California." [66] A trial shipment of ore from the Watterson property sent to a Salt Lake City smelter at this time returned only $40 a ton on the average. This was not considered pay ore because of the long, time-consuming trip involved in getting the ore to Cuprite, north of Bonnie Claire and over sixty miles away. According to McAllister the first recorded production from property in the Ubehebe District was of silver from the Ubehebe Mine in 1908. [67]

For the next few years mostly assessment work was performed on the claims, and no startling discoveries were recorded. Development was primarily impeded by lack of water and other hardships associated with desert prospecting. In an attempt to solve the transportation problem, Watterson and Farrington made an agreement with a Frank A. Campbell to transport ores from the district by means of a Vuba ball-tread tractor, beginning with an initial trial run of 500 tons of ore. The outcome of this novel experiment was eagerly awaited by other mine owners in the area who were tired of the inadequacies of an animal-powered transportation system. Because it had heretofore not been worthwhile to perform extended development work, the depth of ore bodies in the Ubehebe Mine was not known, but the surface showings were immensely promising. [68]

The auto-tractor project turned out well, and in March 1916 Campbell was not only still hauling lead ore in the Ubehebe region, but manganese as well from Owl Holes to Riggs across the southern part of Death Valley. Production from the Ubehebe Mine now was sporadic, but reached a peak in 1916 when 254 tons of ore running 15% lead were shipped. [69] By 1917 development at the mine consisted of two tunnels, an upper one 60 feet long and a lower one 100 feet long, connected by a fifty-foot winze. Two ten-ton-capacity Yuba tractors still transported the ore to Bonnie Claire in a fifty-two-hour round trip at a cost of $8 per ton. By April the mine's three employees had produced 200 tons of 60% lead ore. [70]

The Copper Bell property, along with the Copper Queen-Blue Jay and Bonanza-Hessen Clipper, shipped a few tons of copper from 1916 to 1918 when prices were high for this commodity. The deposits in this mine were fairly high-grade, and much of the copper production reported from the Ubehebe Mine (over 15,000 lbs.) probably actually came from the Copper Bell workings, 1,000 feet east of the Ubehebe Mine on a southwest-facing hillside and controlled by the same owners. [71]

During the fall of 1920 some lead-silver-copper claims said to have been owned for many years by Arch Farrington were sold to the Arrowhead Rico Company of Tonopah for $125,000. A small crew went to work, primarily in an upper and lower tunnel. Fifty tons of ore had been sacked by January 1921 and it was estimated that three truckloads of ore would be sent to Salt Lake City monthly. The transportation cost would be $15 a ton to Bonnie Claire and $12 per ton over the railroad to the smelter. Sol Camp was installed as manager of the mine, which closed with a drop in lead prices. [72]

In 1922 W.W. and M.Q. Watterson and spouses deeded to Archibald Farrington. and J.H. Crook of Tonopah all their interests in the Smith-Watterson-Farrington mines. This transaction included the Butte Nos. 7-10, West Extension Butte No. 3, west half of Butte No. 6, Copper Bell No. 1, Copper Bell, and other properties. Crook and Farrington then deeded a one-third interest in these claims, plus the Copper Bell Nos. 4-6, to Charles E. Knox; smaller interests in these were later deeded to the Montana-Tonopah Mines Company and to Andy McCormack. [73]

The next step in the Ubehebe Mine's development was leasing of the property to Fred Dahlstrom and the Finkel brothers of Tonopah, Nevada, in 1928. The Snyder stope was opened about this time and turned out to be a very profitable venture. After paying $15 a ton transportation costs, the lessees netted $55,453 from twenty-five carloads of lead carbonate shipped to the U.S. Smelting, Refining and Mining Company at Salt Lake City. The ore averaged about 64% lead, 17 ozs. silver, 704 gold, and 1.7% zinc, and because of its adaptability for flux, gained for its shippers an additional $1 to $3 per ton bonus. The maximum annual recorded production of lead and silver for mines in the Ubehebe area in 1928 was attained by the Ubehebe Mine, which produced 1,120,343 lbs. of lead, 1,523 lbs. of copper, 15,222 ozs. of silver, and 17 ozs. of gold. [74]

Lead and silver mining was much less active in 1929 when lead prices dropped. The California lead output was down about 600,000 pounds from the previous year, and the number of miscellaneous shippers in Inyo County had vastly decreased. Principal lead producers listed in the Ubehebe District were the Estelle (?) and Butte. In these later years the Ubehebe Mine's production varied from 22 tons in 1929 to 379 tons in 1951. [75] Most development work was done prior to 1930. The Tramway stope was not mined until the tramway was installed, and then is said to have produced nine carloads for the lessees, one of which netted over $5,000. The No. 4 stope, discovered in 1930 and completely gutted by lessees after that, contained small quantities of molybdenum. Successive lessees after 1930 mostly enlarged the old stopes and cleaned them out in the search for shipping ore. [76] In 1937 Sol Camp returned to the Ubehebe Mine in an attempt to revamp mining operations because of a rise in lead prices. A contract was let to haul the ore to Death Valley Junction for shipment over the Tonopah & Tidewater to the smelter at Murray, Utah.

The Archie Farrington Estate owned the property in 1938, but the nine or twelve claims (figures differ) were under lease to Grant Snyder of Salt Lake City and C.A. Rankin of Los Angeles who were working a crew of ten. Trucks hauled the ore, reportedly carrying 50% to 60% lead with some silver, to Death Valley Junction, and from there it was shipped to Salt Lake City smelters. Principal development consisted of a long tunnel with drifts and crosscuts, with production so far totalling approximately $100,000 in lead-silver ore. [77]

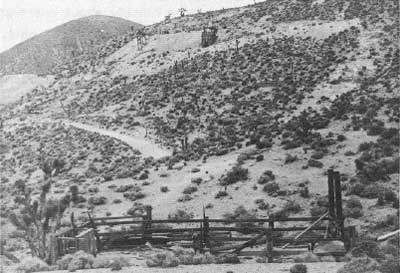

In the late 1940s Snyder was still working the property, which in 1946 consisted of eleven unpatented lode claims: the Butte Nos. 6-10, West Extension Butte No. 3, Copper Bell, Copper Bell Nos. 1-3, and the Quartz Spring Claim seven miles east of the mine. Five principal ore bodies were being worked: the Watterson, Snyder, Flat, No. 4, and Tram stopes. Facilities and equipment at the mine included a cook- and bunkhouse with three rooms, furnished with beds, a stove, and table; a small compressor house with a 100-cubic-foot compressor driven by an auto engine; a small air receiver; a dilapidated blacksmith shop with an anvil, vise, grindstone, and workbench; four mine cars; one jackhammer; and a tramway cable. [78]

The maximum recorded annual production of zinc in the Ubehebe District in 1948 was 53,854 pounds from the Ubehebe Mine. [79] Camp facilities in 1949 remained about the same. In the gulley near the portal of the main tunnel was one house with two large bedrooms and a kitchen, provided with beds and a coal cookstove, while a partially constructed house nearby could be completed for a second bunkhouse if needed. This complex adequately served about five to seven men. The mine workings consisted of two major tunnels, three short ones, and several cuts and shallow shafts penetrating the steep ridge. The Tram tunnel was located on the opposite side of the ridge from the camp, about 200 feet above the main tunnel. Ore from here was transported to the ore bin at the lower tunnel portal by a single-bucket tramway operated by a ten-horsepower gas engine on top of the ridge. Wheelbarrows brought the ore out of the tunnel to the tramway terminal. The Ubehebe Group now consisted of thirteen unpatented lode claims--the Butte Nos. 3-10 and West Extension Butte #3 in the lead zone, and the Copper Bell and Copper Bell Nos. 1-3 in the copper area to the east--plus the Quartz Spring Claim. No water supply existed on site, so that during shipping periods this precious commodity was hauled back from Beatty on the ore trucks and at other times one of the nearby springs was tapped and water stored in large drums on site. Total production of the mine at this time was estimated at 5,000 tons, containing 20% to 60% lead, an amount of ore that at the current 1949 market price exceeded $250,000 in value. Ore was hauled to Beatty, Nevada, and then either on to Las Vegas for rail shipment to Salt Lake City or trucked directly to Salt Lake City through Tonopah and Ely. [80]

In 1966 a lease/purchase agreement between the Ubehebe Lead Mines, Inc., and Basic Resources Corporation was initiated, but development was disappointing and BRC's interests were later quitclaimed back in 1968. [81] Ubehebe Lead Mines Company has owned the property ever since. Revised estimates of the total tonnage produced by the Ubehebe Mine are placed at about 3,500 tons, averaging 38% lead, 7% zinc, 12 ozs. silver, and .02 oz. gold per ton. The Copper Bell claims have averaged about 16% copper. [82]

|

| Illustration 237. View north of mine workings and aerial tramway, Ubehebe copper-lead Mine. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 238. View toward southwest of residential area across road from mine workings. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

(b) Present Status