|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION III:

INVENTORY OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES THE WEST SIDE

B. Emigrant Wash and Wildrose Canyon

1. Thorndike Camp

a) History

Thorndike Camp, located between the Charcoal Kilns and Mahogany Flat, in the Wildrose section of the Panamints, was once part of a 160-acre homestead filed on by John Thorndike (Thorndyke), a well-known Owens Valley miner, in order to provide a pleasantly-cool summer retreat for his wife Mary, an area schoolteacher. Thorndike came to the Death Valley region in 1903 from Maine, where he was born and had attended college. Working first as an assayer at the Ward Mine in the White Mountains, he later moved to mines in the Coso area and around Darwin. During these years he is mentioned in connection with the Modock Mine, which he superintended, [1] and the Custer Mine, near Darwin, which he co-owned and managed. In 1920 he married a Darwin schoolteacher, Mary K. Stewart. [2]

Thorndike's next move was to Ballarat, where his name was linked to the rich Gibraltar silver-lead mine in South Park Canyon, which he supervised, [3] and to the Big Horn lead-silver property eight miles southeast of the town that was one of four claims comprising the Honolulu Mine, worked intermittently from 1907 on, producing mainly during World War II. Thorndike was superintending the latter property in the 1920s over a force of fifteen miners who were building a five-mile auto/truck road to connect with the Ballarat-Trona road to be used for heavy ore shipments to the smelters. It has been said that this was the first mine to ship ore from the Panamints by truck. Thorndike's contribution to the area's development must have been considered substantial, for South Park Canyon has also been known as Thorndike Canyon. [4] In the late twenties Thorndike also held half interests in the Sunrise, Pine Ridge, and Panorama Nos. 1 to 5 mining claims, mining district unknown. [5]

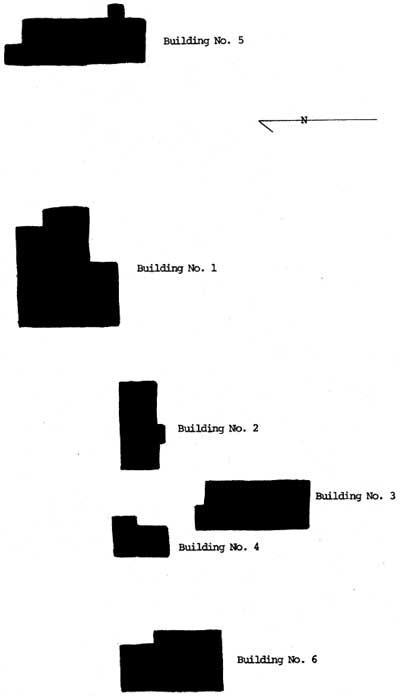

Around the mid-1930s Thorndike filed on a 160-acre homestead in the Panamints at the eastern end of Wildrose Canyon, the property extending from the bottom of the canyon up as far as Mahogany Flat and climbing about 600 feet in elevation. Six structures were erected by the couple in the approximate center of their holdings, including:

living quarters, a two-room frame building with an attached screened porch;

a cabin, a two-room frame building;

a kitchen/dining room, a two-room structure;

a laundry/shower room, a frame building with access to hot and cold water;

a sleeping cabin, a two-room frame unit with an attached screened porch; and

a garage/shop, a two-room, dirt-floored frame structure housing the complex's electrical plant. [6]

|

|

|

|

Although originally the Thorndikes presumably planned to occupy this property only a few months each summer, because of the number of buildings erected it is possible that they later envisioned developing the area for commercial purposes. This seems to be substantiated by a 1939 newspaper article reporting the unbelievable story that a Trona, California, man had been given permission to build a ski lift above the Charcoal Kilns near Telescope Peak; in connection with the skiing operation, it was mentioned that guests visiting the lift will find comfortable accommodations at Thorndike's camp." [7] The Thorndikes lived intermittently on the property until 1954; in 1955 the entire 160-acre homestead was bought by the U.S. Government and integrated into Death Valley National Monument.

b) Present Status

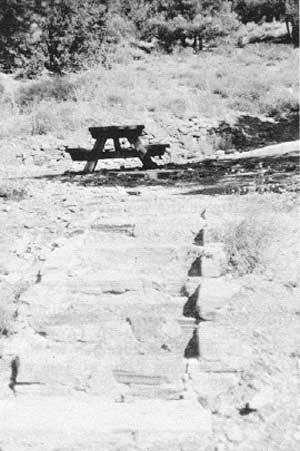

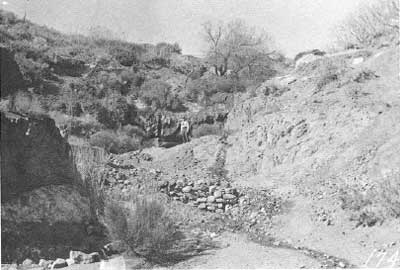

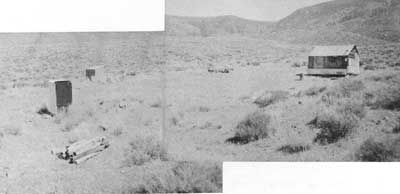

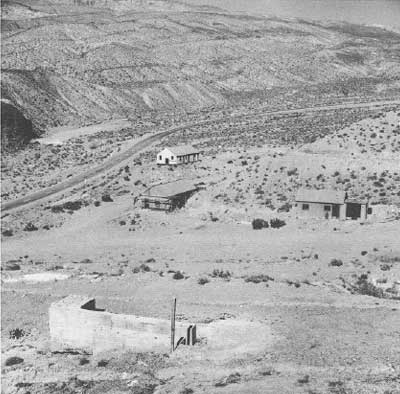

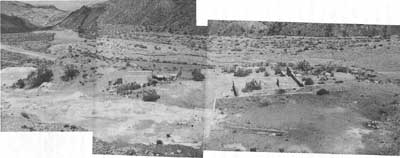

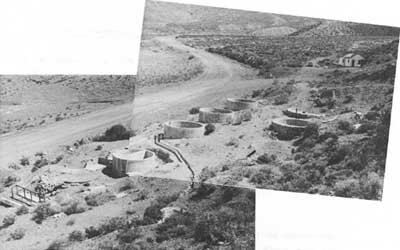

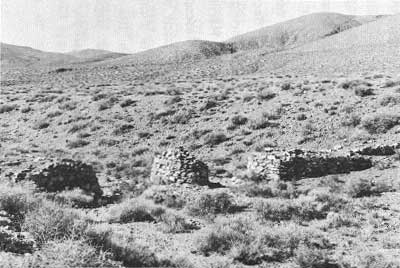

Thorndike Camp is located about 3/4 of a mile beyond the Charcoal Kilns, and is reached via a steep, low-gear road that continues on through the campground to Mahogany Flat. No buildings are standing on the site, although some concrete slab foundations are visible, as well as the remains of a small fish pond, a stone stairway, and some stone retaining walls.

c) Evaluation and Recommendations

The Death Valley Shoshone were attracted to the Wildrose area of the Panamints as soon as the summer heat began to force its way into the lower elevations of the valley. The area around the present Thorndike Campground was especially inviting as a summer campsite because of the presence of several springs in the area as well as the pleasant coolness of the surroundings due to the narrowness of the canyon and its relatively high elevation. These were undoubtedly also the attractions that led John Thorndike to homestead there. [8]

|

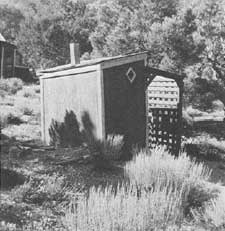

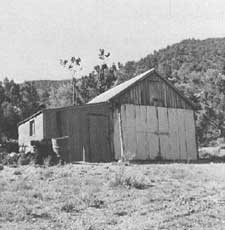

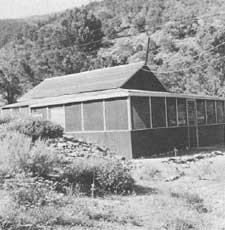

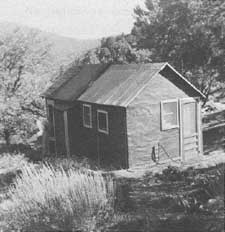

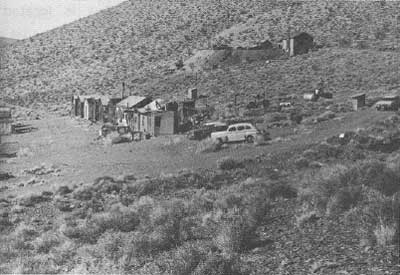

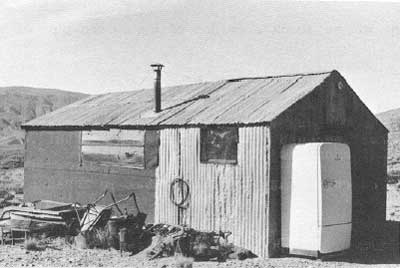

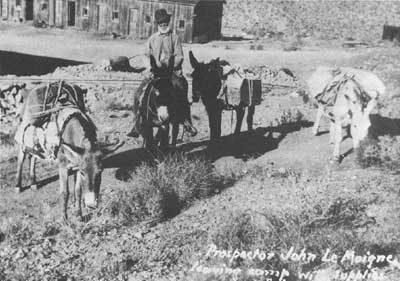

| Illustration 119. Thorndike Homestead. From Hopper, "Appraisal of Thorndike Property," 1954. |

|

| Illustration 120. Goldfish pond (?) at Thorndike Camp site. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 121. Stone steps and wall in background are all that remain of Thorndike homestead. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

No significant remains of the Thorndike homestead are found in the campground. Despite its earlier association with a well-known Death Valley region prospector, the site no longer possesses historical integrity or significance.

2. Wild Rose Mining District

a) Early Activity

Referred to from about 1873 to the spring of 1888 as "Rose Springs District, the area loosely bordered by the Panamint Mining District on the south, Townsend Pass on the north, Panamint Valley on the west, and Death Valley on the east, was first opened to easy access from the Panamints by W. L. Hunter and J.L. Porter, who had located some promising claims in the vicinity. [9]

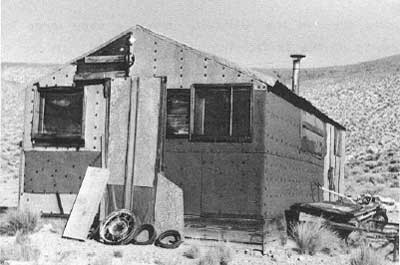

By March 1876 the district was seeing a vast amount of activity. The Inyo Mining Company had bought seven well-defined ledges in the area and had set up headquarters at the North Star Mine (formerly owned by the Nassano Company). The start of operations there and at the Garabaldi (Garibaldi) was only awaiting the arrival of Remi Nadeau's freighting teams bringing needed tools and stores. A townsite was being laid out to house the many miners entering the district over the improved wagon road from Warren Springs in search of work and property:

There are other valuable ledges in the district, and ample room for other companies to invest; and, as spring advances, we will, no doubt, have quite an influx of capital, as there are several parties of prospectors who have been in here at times for a year or more, and who hold ledges of considerable merit, from whom capitalists can purchase a set, or even several sets or groups of. ledges, numbering from three to 10 or 12, and which now lie undeveloped, together with mill sites with sufficient water for milling their ores. The records show that about 165 ledges have been located, and the necessary amount of work performed on the most of them to hold them for the year. [10]

b) First Locations

By 1882 the area was being referred to variously as the "Wild Rose District", and "Rose Spring Mining District," although the former designation was not official until several years later, It was rumored that a silver mill was soon to be erected because of the profitable and immense ledges being struck, and indeed a notice of location was filed on Wild Rose Spring itself for "conducting and carrying on a General Milling and Reduction Works." [11] Property filed on during this period included the Inyo Silver Mine, 113 miles North from Rose Spring and adjoins SE quarter of Virgin Mine"; Blizzard Mine "5-1/2 miles East from Emigrant Spring on right-hand side of trail leading from Mohawk Mine to Blue Bell Mine and is about 8 miles air line north of Telescope Peak"; Valley View Mine "6 miles East of Emigrant Spring on Mineral Hill & lies on right-hand side of trail leading from Springs to Blue Bell Mine & is ca. 2 miles SW of latter"; Argonaut Mine (Nellie Grant), "situated about four and 1 miles South, from the Mouth of Emigrant Canon at what is known as Hunter & Porters rock house near Emigrant Spring & is immediately South of the Jeannetta [Juniata?] Mine and is a relocation of the Uncle Sam Mine"; and the Jeanetta Mine "on the West side of Emigrant Canon about 4-1/2 miles above . . . near Emigrant Spring and is a relocation of the Nellie Grant Mine." [12]

In July 1884 the Mohawk (earlier known as North Star), Blue Bell (aka Garibaldi), and Argonaut (aka Nellie Grant) mines shipped about ten tons of ore to the smelter that yielded over 3,000 oz. of silver bullion. Due to the lack of milling facilities in the Wild Rose area, it was necessary to ship the ore across the Panamint Valley to the ten-stamp plant of the Argus Range Mill and Mining Company in Snow Canyon. This tedious trip was undertaken by the owner of one of these properties who

is a strong believer in this district . . . . The milling test was very satisfactory, coming up to 85 and 90 per cent of the assay value by the most ordinary process, and bullion 75 and 80 fine, carrying a light per cent of copper. This district shows a large amount of high grade ore. Some of the most promising ledges have been considerably developed, giving encouragement that they will make mines of great and permanent value. Natural and good roads lead to these properties and to the wood and water, which are both found ample for mining and milling purposes and are contiguous to the mines. There are hundreds, and I may say thousands of tons of this fine milling ore out and in sight, and no milling facilities near at hand to work it profitably, and the owners, mostly miners, are unable to undertake the erection of reduction works. The climate is very healthy and the finest in the world for continuous mining. [13]

By this time other producing mines in the area are mentioned: the Juniata (possibly the Jeanetta mentioned earlier), contiguous to the Argonaut, and the Virgin six miles south of these and near the Blizzard. Because of the encouraging results at the Snow Canyon Mill, the owners of the latter two were endeavoring to find capital to finance construction of a ten-stamp mill in the area of the mines. [14]

c) Formation of District and Establishment of Boundaries

On 4 April 1888 a formal meeting of local miners was held at Rose Springs for the purpose of organizing a new mining district in light of the fact that all the books and records of the previous district had been lost and no recorder had been active for the last two years. The new entity was to be known as the "Wild Rose Mining District": "The north boundary line shall be Townsends Pass in the Panamint range of Mountains. The western boundry [sic] line shall be Panamint Valley. The Southern boundry line shall be the North line of Panamint District. The Eastern boundry line shall be Death Valley." [15] A later description of the Wild Rose District, whose boundaries were possibly expanded after the strike at Harrisburg, reads:

Beginning at Williams canon to the center of Panamint Valley, thence north to a line running east and west through Cottonwood canon to Surveyors' Wells, thence to Salt Creek, south to Bennett's Wells, and west to place of beginning. The district is adjacent on the south and west to the recently organized South Bullfrog district. [16]

More mines were recorded during this time: the Weehawken (Weehawker?) Mine "about 2-1/2 miles from Coal Kilns in northerly direction and about 7 miles in westerly direction from Death Valley"; Antimony Mine "2-1/2 miles from Rose Springs on south side of road leading to coal kilns and 1/2 mile from summit of mountains leading to Fever [?] Canon"; Consolidation Mine "1-1/2 miles south from North Star Mine and formerly known as Consolidated." [17]

d) Mining Companies and Further Locations

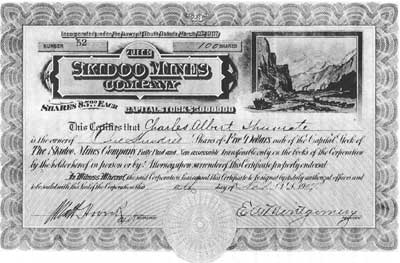

By 1906 several mining companies held interests in the Wild Rose District: the Telescope Peak Mines Syndicate was an Arizona incorporation with a treasury stock of 600,000 shares, owning seven gold and copper claims covering about 140 acres in the Wild Rose District. Offices were maintained in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Phoenix, Arizona; [18] the Panamint Mountain Mines Syndicate, another Arizona incorporation under the same management as the Telescope Peak Company, with a treasury stock also of 600,000 shares, owning sixteen full gold claims covering 320 acres each in the Wild Rose District; [19] the Wild Rose Mining Company, whose interests were represented by W.B. Gray, Dr. U.V. Withee, and W.H. Sanders, and which owned gold, silver, copper, and lead properties with surface values ranging from $9 to $716 (by 1924 the company's property above Wild Rose was proving to be one of the big gold and silver mines in the district under the management of Charles Grundy. Nineteen thousand tons of ore assaying $29 per ton were ready to be mined, and by March the ore was assaying $300 to $500 a ton in silver, with gold and lead present, too); the Rush Company, owning prospects near the Wild Rose, and involved in building a road into the canyon; the Death Valley Gold Mining Company recently incorporated by California capitalists; and the Kawich-Bullfrog Company. The Wild Rose, Rush, Kawich-Bullfrog, and Death Valley Gold Mining Company properties were all stated to be approximately two miles from Harrisburg. [20]

Other mines mentioned at this time, but on which no further information was found, are the Last Hike, Venus and Mars groups of claims located by Tom Knight in the Wild Rose District. [21]

e) Heliograph Dispatches

An interesting technological development related to mining during this time involved the initiation by the Rhyolite Herald of the heliograph method of communication in an attempt to facilitate transmission of the latest news from the surrounding mining districts to its readers:

The latest move is to receive heliograph dispatches from the Funeral and Grapevine ranges, which will be flashed to us from the mountains twenty-five to fifty miles away. Death Valley will signal from the top of Chloride Cliff in the Funeral range, while the California Bullfrog, Doris Montgomery and Breyfogle will flash their news from the Doris camp. Wild Rose district will span Death Valley with a ray of light to the Doris camp and that station will repeat the messages to us.

Who knows but that this wireless telegraph will be the means of saving life? . . . The instruments are now being constructed and as soon as completed and other necessary arrangements made, the signaling will begin. [22]

f) Settlement of Emigrant Spring Brings Need for Road to Keeler

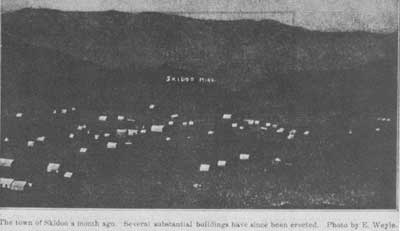

By the summer of 1906 Emigrant Spring(s) was the site of what was projected to be a great mining camp with good ore showings in the surrounding properties that were attracting much investment capital. Thirty men were employed in the area, and there was talk of erecting a twenty-stamp mill. The biggest project under contemplation at this time was construction of a road from Keeler to Emigrant to replace the over-100-mile-long Johannesburg-Emigrant supply route that was costing shippers 4-1/2¢ per pound. The new route would not only reduce this distance by about 45 miles, correspondingly reducing production costs and speeding development, but would also open up a remunerative Owens Valley-Emigrant trade in agricultural products. [23]

A letter from Ballarat in late summer of 1906 declared that results from strikes near Emigrant Spring were still more than satisfactory. Freight teams from Johannesburg were arriving everyday, a pipeline was being built at Skidoo, and there was an influx of mining men from Goldfield and Bullfrog. The two disadvantages seen for the area were its distance from a railroad and the bad reputation the country held for heat and difficulties in mining. [24] By this time the Cashier Mine at Harrisburg, the Sheep Mountain strike, and the Golden Eagle at Skidoo were all in the throes of new development work. [25] By the fall of 1906 the wagon road from Keeler to Emigrant was still not an established fact, although it was being strongly pushed by miners in that section. Darwin Wash was considered to be the most feasible route for the trail, being both cheaper and more direct. [26]

Individual narratives on Harrisburg and Skidoo will follow in later sections. Suffice to say at this point that both were extremely busy at this time, thus ensuring some longevity for the Emigrant (Wild Rose) District. A six-horse stage was running twice a week between Ballarat and Emigrant Spring, where there was a saloon, grocery store, corral, and restaurant. Plans were underway to complete connections on a road from Skidoo to Daylight Springs and then on to Rhyolite. It was justifiably feared by those advocating the Keeler-Emigrant Road that all the potential revenue to be gained in the district could easily be siphoned off to Nevada, and Owens River Valley farmers and merchants would lose out completely:

Get together! Build the wagon road! This means work for Inyo's ranchers and their teams, and when completed will open a market for their produce, where they will not have to submit to extortionate railroad charges. The cost of this road would be trifling compared to the immense advantage to be derived therefrom. The Emigrant-Skidoo-Harrisburg country has arrived and it remains for Inyo's people to profit thereby.

Inyo is now in the limelight from a mining standpoint and it, remains for our County officials and the taxpayers to offer every facility in the shape of good roads and provisions to the host of men who are delving in the mountains and developing the resources of these vast store houses of golden treasures. This will be for the good of the County as a whole. Let no narrow feeling of sectionalism retard the work. [27]

Conditions of life were not easy in the Wild Rose area as shown by an item in December 1906 stating that all work at Skidoo, Harrisburg, and the surrounding country was temporarily stopped because of a heavy snowstorm that had deposited three to four feet of the white stuff in the area. Due to lack of fuel and adequate housing, the only option available to the miners in the section was to leave for lower elevations. In contrast, in August 1908, three or four miles of the Emigrant Wash Road were completely obliterated by a cloudburst, the road being five feet deep in water carrying 50- and 100-pound boulders. [28]

g) More Properties Located Throughout 1940s

By 1907 a few more properties were being recorded: the Combination-Goldfield and Nevada-Tonopah owned by J.H. Allen, Geo. Raycroft, and A.D. Myers; Wild Rose Annex #1, "one mile east from Harrisburg and Joins Wild Rose Group on East," located 1 March 1907 by Weyle and Clewell; Oro Blanco Mine about 3-1/2 miles south of Harrisburg," located 25 March 1907 by Nat Levi, H.L. Culvert, and O.E. Hart; Taylor Mining Claim "2 miles south of Harrisburg and one mile east of narrows on Ballarat Wagon road. Claim is on south side Wood Canyon and joins with Good Dope [Hope?] Mining Claim #2 on west," located 13 April 1907 by 0. Ewing and Wm. Taylor. [29]

Due to the expansion of mining activity and the consequent desperate need for a body of men to adjust and settle the disputes constantly arising over conflicting interests in mining claims and town lots, some important resolutions relative to the location of mining claims in the Wild Rose District were adopted at a meeting of the miners of the Wild Rose District held at Skidoo on 15 April 1907. Besides setting up procedures for marking and recording claims and performing the necessary location work, a motion was adopted to elect a ten-man Arbitration Committee to settle local disputes in the mining community arising over ownership. [30]

In late May 1907 a proposal was mentioned for a turnpike leading from Greenwater via the old Daggett borax road to Furnace Creek Ranch, then to Surveyor's Wells, over Emigrant Pass to Darwin, and connecting there with the road to Independence. The following February roadwork was being pushed between Keeler and Emigrant, with a connection soon to be made to the Wild Rose road. Ten men with two teams were working in the Darwin Wash area. [31] The exact population of the Wild Rose District in the early 1900s is not known. Registration for primaries in 1914 revealed forty-one persons registered in the Emigrant precinct, thirty-nine men and two women. By 1916 there were only twenty-three voters registered there. [32]

In 1923 development and prospecting work were still being carried out in the area, a number of new properties mentioned as being active in the Wild Rose District between 1909 and 1938. Because nothing further is known of them and because rarely is their exact location clear, only brief mention of them will be made:

1. Two Friends Nos. 1, 2, and 3.

2. Silver Star Nos. 1, 2, and 3 and Old Spanish Mine

3. White House and White House Nos. 1, 2, and 3.

4. Snowfall and Snowfall Nos. 1-11 approximately 240 acres, owned by the Golden Glow Mines Corporation of Utah.

5. Veta Grande de Plata Nos. 1-6 at Emigrant Spring.

6. Chesamac Mine six lead and silver claims eighteen miles northeast of Ballarat, development in 1926 consisting of shallow tunnels and open cuts worked by two men.

7. Mother Lode three miles east of Emigrant Spring.

8. Yellow Horse Mine

9. Western Mine Western No. 2, adjoining the Moonlight Mining Company property (in Nemo Canyon?).

10. Extension No. 1 Mine

11. Big King Mine

12. Edna Nos. 1-3.

13. Treasure Hill Mine twelve claims comprising 488 feet of shafts and tunnels in 1938. [33]

One of the more substantial mining companies formed in the district in the late 1920s was the Emigrant Springs Mining and Milling Company started by H.W. Eichbaum and associates in 1929. (More details on this company will be presented in the Skidoo section of this report.) In the 1940s the Skidoo District underwent a revival of mining activity. Both the Skidoo Mine and the nearby Del Norte Group were being actively developed as was the Gold King Mine one mile east of Journigan's Mill. Other mines functioning from this period on were the: Emigrant Mine three lead and silver claims active in the 1940s; Rose Mine four tungsten claims comprising an unsightly deserted camp along the charcoal kilns road, registering no production or mining activity since the mid-1950s; and the Wildrose Mine four silver claims last worked in the late 1950s. [34] Also during the fifties sporadic tungsten exploration was carried out in the vicinity of Skidoo.

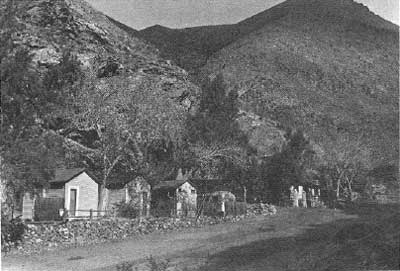

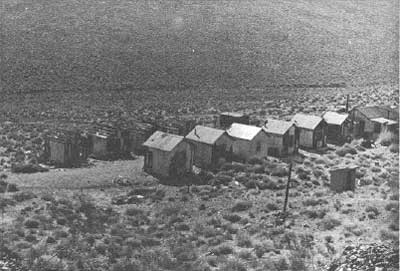

h) Historic Wildrose Spring Stage Station

At least one historical resource of the Wild Rose area met its demise in the early 1970s. This was Wildrose Station, once located about mile below Wildrose Spring on the main road through Wildrose Canyon. Its service to the public began as a shady oasis providing a water spot and resting place for prospectors and mule teams, possibly as early as 1878; it then functioned as a stage station on the Ballarat-Skidoo route from about 1908 to 1917. The site consisted then of a wooden station, a corral, and blacksmith shop. After World War I the site saw only intermittent occupancy, but by the early 1930s offered cabins, a small curio shop/store, eating facilities, and gas to tourists. Composed of structures reputedly moved on site from abandoned mining camps about 1932, the camp was deemed unsuitable for modern tourism, and it was recommended that all the buildings except for the nineteenth-century forge site be destroyed. The concessionaires were forced to vacate the premises, which soon fell prey to vandalism and finally destruction. Today only foundations remain, topped by a few picnic tables and a comfort station. According to one author, this was the location of the miners' meeting in 1873 that organized the "Rose Springs Mining District." [35] If true, it may also have hosted the 1888 meeting that created the Wild Rose Mining District.

|

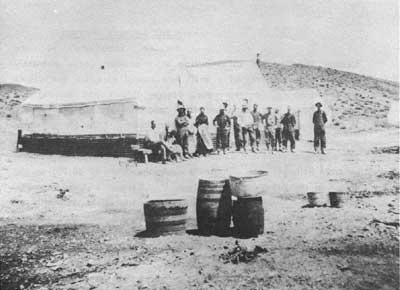

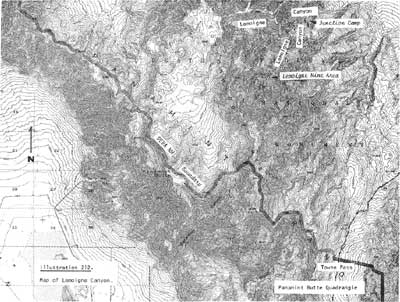

| Illustration 122. Emigrant Spring in Emigrant Canyon, no date. Photo courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

| Illustration 123. Wildrose Station in Wildrose Canyon. These cabins are atop the site of an old stage station serving the Ballarat-Skidoo run. Photo by W.F. Steenbergh, 1964, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

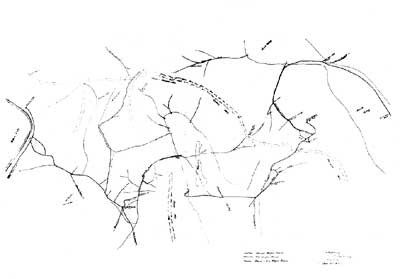

| Illustration 124. Wagon roads in western Death and Panamint valleys. Plotted by A.M. Strong, county surveyor, July 1907. Note Wildrose Station, where John Callaway (Calloway) operated a cafe at this stage stop between Skidoo and Ballarat. Note also the Indian Ranch on Cottonwood Creek just to the left of Lost Valley (upper arm of Death Valley). This feature will be discussed later in the section on Hunter Ranch. Courtesy of Inyo Co. Recorder, Independence, Ca. |

i) Sites

(1) Wildrose Canyon Antimony Mine

(a) History

i) Possible Site of Earliest Mine Location in Monument

It has been suggested that the Wildrose Canyon antimony deposit in the Panamint Range was found in 1860. An early discovery date would seem to be supported by a letter from Rose Springs appearing in the Panamint News in 1875 listing mines in the general vicinity: . . . and last, but by no means least, the Old Combination Company's ledges, situated about three miles southeast of here, and discovered by Dr. George some twelve years since, and now placed under the management of A.A. Ringold, who is also one of the pioneers of this and Slate Range District of twelve years ago.

The mines of this company have quite an interesting history. Shortly after their discovery a company was formed and men put on to prospect the ledges; the men were driven out by Indians in the Spring of 1863, and four of the party killed; since then their ledges until now have remained idle. [36]

Chalfant, in speaking of the discovery of the Telescope District in 1860, states that "W.T. Henderson was named as superintendent of the Combination mines." [37] Later in this article he remarks that "the antimony deposit near Wild Rose spring, in the Panamints, was found during this period, if we accept the evidence of a chiseled 'July 4, 1860,' in its tunnel." [38] Wheat, however, states that on Christmas Day, 1860, the party [George expedition of 1860] crossed over into Wild Rose Canyon near the site of the present Death Valley National Monument Summer Headquarters, and on that day discovered a deposit of antimony ore which was appropriately named the "Christmas Gift Lode." This was the first mining claim to be located in the Panamint Range . . . ." [39]

According to information acquired by Richard Lingenfelter, at the University of California at San Diego, a Combination Gold and Silver Mining Company was incorporated on 26 July 1861, controlling over 9,900 feet of claims worth approximately $990,000 in the Telescope District. Dr. George was president of the company, which in 1862 owned the Christmas Gift and other nearby mines.

The first official documented evidence of what might be this mine found by the writer was a notice of location recorded on 8 August 1882 by Frank Beltic and filed on the "Original Antimony Mine in Rose Spg. Mng. Dist. 2-1/2 miles SE of Rose Spg. AKA Inyo Antimony Mine." [40] Also found was a location notice for the Inyo Antimony Mine, giving the same location as above, and filed the same day by Chris Crohn, Paul Pefferle [sic] Frank Betti, and S.D. Woods. [41]

ii) Antimony Mining in the Region

The antimony industry in the United States was still in its nascent stages in the 1880s and was centered completely in the western states. Extensive reduction of antimony ores was taking place in Utah by 1884, and deposits also existed in Nevada. Up to 1892 most of the entire small output of antimonial ore produced in the United States came from California mines. Occurrence in the Death Valley region encompassed southern Esmerelda County, eastern and southeastern Inyo County, and northern San Bernardino County, with the Panamint deposits situated approximately in the middle of this belt. [42] None of the attempts to work these western deposits had so far proved successful.

Throughout the next few years the Wildrose antimony deposit underwent very little active development work, even though by 1887 this metal was quoted at $150 per ton in London. [43] Obviously the site's remote location and the lack of investment capital, coupled with a still undeveloped market, precluded any serious mining operations here. In January 1889 mines in this same general area were relocated and filed on by a William Hannagan (Hannigan or Harrigan) and a Joe Donalson (Danielson). [44]

The extent of mining accomplished by these men is unknown, but that the mines were regarded as potentially lucrative is evidenced by the fact that a year later they were bonded for $3,000 to G.A. Smith, a real estate dealer and mining speculator of Los Angeles, who intended to work the property and possibly build a reduction plant in the vicinity. [45]

Smith's optimism about the mine's future was based in large part on his assumption that a railroad would soon be extended from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles, putting the valuable mineral deposits of the Panamint country within easy reach of cheap transportation. But until that longed-for and necessary event took place, he declined to expend money on mine development. [46]

By 1891 antimony mining was showing signs of increased activity and of becoming an established industry. Over near Austin, Nevada, in Lander County, antimony mining was becoming highly profitable by that year. An English syndicate was working some mines in the area and making regular shipments to Liverpool, England, for reduction. The ore was averaging over sixty-five percent antimony per ton, and at the production rate of nearly 100 tons of ore a month from the mines the company was able to declare two dividends. Still, most of the antimony ore needed in the United States came from foreign producers, such as Borneo, the European states, Algeria, Australia, and New South Wales. The major use of antimony during this period was as an ingredient in certain alloys, providing hardness and stiffness, and a lesser use was in medicinal salts. Because of its somewhat restricted applications, the market for the metal was still limited. [47]

By 1893 reduction works for antimony ores had been established in San Francisco and were treating ore from California and Nevada, the latter state having eclipsed the former in production of this metal. That year the total output of antimony was 200 tons, estimated in value at $36,000. Four hundred tons of ore had produced this amount of antimony, of which California supplied fifty. The Wild Rose Mine, comprising eleven claims, was evidently furnishing slight amounts of ore at this time, although lack of capital was still preventing its full development. The deposit on the north side of Wild Rose Canyon was also opened at this time. [48]

iii) Development of the Monarch Combination and Monopoly Mines and the Kennedy Claim

In January 1896 three notices of location were filed by Frank C. Kennedy: one for the Monopoly Mine, two miles from Wild Rose Spring and composed of the former Hillside and Intrinsic mines; a second for the Monarch Mine, 1-1/2 miles from Wild Rose Spring and comprising the former Antimony and Smokeless Powder mines; a third for the Combination Mine, joining the Monarch, about 1-3/4 miles from Wild Rose Spring, and composed of the former Jersey Bell, Lotta, and Helen G. The Kennedy Claim was first located on 1 January 1897. [49]

In 1900 Frank Kennedy's antimony mines in Wild Rose Canyon were bonded to George Montgomery and E.M. Dineen, two Los Angeles men who later, in association with a C.B. Fleming, bought them in anticipation of building a wagon road to Darwin and of erecting a twenty-five ton smelter nearby, enabling production on a large scale. A contract was immediately let to haul the ore, which could be shipped to San Francisco and New York. [50] The first carload of antimony ore shipped by the new owners left Johannesburg in September 1900, with expectations high of a good return and the incentive thus provided to actively push further work. The success of this initial shipment was either not reported or the statement simply not located by this writer, but by the next year, Inyo County was leading in the California production of lead, soda, and antimony ($700 worth). [51]

By November 1901 the four mines of the Wildrose Group were being developed by an eighty-foot-long open cut and four tunnels, all producing-ore reportedly averaging fifty percent antimony. [52] The pattern of ownership of the Wildrose claims is difficult to follow during the early 1900s. In 1902 a forfeiture notice appeared in the Inyo Independent issued by A.W. Eibeshutz and directed toward C.B. Fleming, J.S. Stotler, and E. M. Dineen, referred to as co-owners of the Monarch, Combination, Monopoly, and Kennedy mines in the Wild Rose Mining District. In 1903 the only reference found to the mines suggested that work had been stopped, evidently due to the lack of good transportation facilities. [53] Frank Kennedy is again mentioned in connection with ownership of some Wildrose antimony claims several years later, in partnership with a Jeff Grundy, J.T. Hall, and Miles Sargent. A gold, silver, and lead strike was reported on their antimony property in 1907, causing some mild excitement in the area. Whether this encompassed the subject claims is uncertain, because several mineral properties had by now been filed on in the area by various individuals. [54]

By June 1909 Frank C. Kennedy was understood to be the owner of the "large and entirely undeveloped deposit of valuable antimony ore . . . in Wild Rose Canyon . . . between Keeler and Skidoo. . . ." [55] By this time Kennedy, J.S. Stotler, and A.W. Eibeshutz had already secured a patent on the property, having held the ground through the years by annual assessment work. According to other records found, however, the Monarch, Combination, and Monopoly claims, referred to as the Monopoly Antimonium Group and comprising forty-two acres, were patented on 11 October 1909, in the name of George Montgomery et al (Mineral Patent No. 83128). [56]

The Inyo Register reported in 1914 that J.E. (?) Eibeshutz and Frank Kennedy sold the antimony mines at Wildrose to some capitalists envincing an interest, as earlier parties had, in erecting a smelter and possibly a furnace to process the silver-lead ores found in association with the antimony. [57] Apparently by late fall of 1914 construction of reverberatory, oxidizing, and blast furnaces had finally started in Wildrose Canyon, with a force of fifteen men expected to begin operations by December.: Probably the new operators felt that the impending war would have a healthy effect on the metal market and make the concentration of low-grade deposits practicable. The current owner of the antimony property was L.C. Mott of San Francisco, whose interest in the reduction plant at this time was purely on an experimental basis, to determine if the antimonial matte could be refined to a pure enough state to make the plant economically worthwhile. By January 1915 twenty-two men were working in thirty openings on the property. [58]

By April 1915 from five to ten trucks, each averaging three tons of ore per day, were making daily trips to the railroad depot at Trona. From there ore was shipped to the Merchants' Finance Company smelter near Los Angeles. A six-ton reverberatory furnace about two miles from the mine was still treating the sulphide ore, which was being found in promising quantities and of a commercial grade. [59] The antimony mines shut down temporarily in the fall of 1915, for reasons not disclosed. By May of that year title to the property had been transferred from Mott to the Western Metals Company of Los Angeles. During Mott's ownership hundred of tons of high-grade ore had been shipped, running about fifty to seventy percent antimony. Because prices for the ore were fairly high (49¢/lb.) during that time, some profit accrued. Probably the mine was shut down either because of the wretched condition of the roads over which the trucks had to haul the ore to Trona or because the price of antimony soon dropped to under 30¢/lb. In December, however, the property was again shipping--six tons of ore a day--using Mexican contract labor. Despite its last slowdown, the Wildrose Mine was hailed as the largest individual producer of antimony ore in Inyo County for the year 1915. [60]

In 1917 a description of the Wildrose Mine reported that many of the early open cuts and drift tunnels had either been filled or had caved in, so the extent of workings was almost impossible to estimate. Currently thirty Mexican laborers were hand drilling and picking the open cuts and sorting ore from old dumps on the property. Five 2-1/2-ton auto trucks were hauling the ore, averaging around thirty-five percent antimony, the forty-five miles to Trona for shipment to the company smelter at San Pedro, California. [61] Greatest production from the property seems to have occurred during the years of World War I, during which time Western Metals Company reportedly mined about 4,000 tons of ore containing thirty-five to forty-two percent antimony. Recovery from the nearby smelter was low, however, and actual production was probably less than 1,000 tons. [62] From 1918 to about 1936, activity on the Wildrose Mine property, consisting of the four patented claims plus several held by location, was sporadic. [63]

By 1938 small-scale operations were occasionally attempted at the mine. An E.B. and Margaret Spitzer of Trona screened ore on the Monarch dump and also attempted some mining on the Kennedy Claim. Their Denver Mine (exact location unknown to the writer) in Wild Rose Canyon produced a small amount of antimony ore that was treated at the nearby mill. The property owners, A.C. MacClure (McLure) and A.G. Barnes of Los Angeles, were pondering whether or not to treat the low-grade ore and that on the dumps, while a T. F. Pierson and Associates of Los Angeles were busy locating eleven other claims in the area. [64]

In 1951 the four patented claims (Monarch, Combination, Monopoly, and Kennedy) were owned by James C. Davis of Los Angeles, the Andrew G. Barnes Estate, the A.C. McLure Estate, and Ruth F. Bastanchury. In 1972 when the Monarch, Combination, and Monopoly claims were appraised by mining engineers, Mrs. Bastanchury (then Mrs. Boeckerman) held an undivided 3/4 interest in the property, while Carl D. Dresselhaus and Lawrence J. Rink shared the remaining 1/4 interest, acquired by a tax deed. The property had been briefly leased for a period in 1970. [65]

(b) Present Status

The Monarch, Combination, and Monopoly patented claims, along with several unpatented ones, are located in the Wildrose Mining District on the south side of Wildrose Canyon in the Panamint Mountain Range about 2-1/2 miles southeast of the Wildrose Ranger Station. They are located on and near Antimony Ridge, extending over the ridge into Tuber Canyon, at elevations ranging from 5,500 feet to 6,400 feet. These three claims form an L-shaped parcel of 42.33 acres reached by an unimproved jeep road veering south for roughly a mile off the graveled road that leads west to the ranger station.

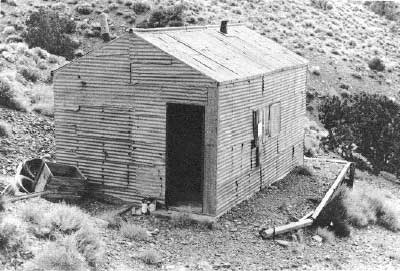

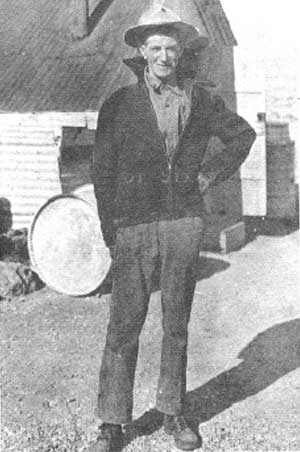

When Western Metals Company was working the Wildrose Mine during World War I, the mine workings consisted of several open cuts and narrow tunnels. According to pictures taken at the time, the ore mined high up on the slopes of Antimony Ridge was hauled by burro train to a long ore chute descending down the hillside to a bin. The nearby mining camp consisted of a combination of frame structures and large tents. [66]

The Monarch workings today consist of open cuts, small adits and stopes, and inclined shafts; the Combination Claim contains an adit and open cuts; and the Monopoly shows an open cut and rat holes. The road to the property ends at the main open cut on the Monarch Claim, and from there trails must be taken to the other workings. A dump area nearby contains purple glass fragments and bottles, indicating early activity. There are no structures on the property.

The Kennedy veins, formerly known as the Wildrose Mine, are reached by jeep road on the north side of Wildrose Canyon, about two miles north of the Monarch deposit, and about 1-1/2 miles northeast of the Wildrose Ranger Station. They are located on a small ridge at an elevation of about 5,100 feet. Workings consist of open cuts and small adits. No structures exist here either. [67]

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

Antimony development in the western states was mildly successful, first in Utah and Nevada and then in California. The Wildrose deposits in Death Valley are in a poorly defined district that saw only sporadic activity through the years, full commercial development of the deposits here being hampered by their remoteness, the consequent lack of good transportation facilities, their small size, and an unsteady market. Their highest production level was reached during World War I--about 1,000 tons--while the other antimony deposit within the monument, the Old Dependable in Trail Canyon, produced mostly during 1939 to 1941, but only about 70 tons worth. Several antimony mines have operated in California. In 1915 when the Wildrose Mine was the largest individual producer, there was one other operation in Inyo County (near Bishop), five in Kern County, and one in San Bernardino County. [68] Other deposits in Inyo County were later found in Trail Canyon in the Panamint Range and on the west slope of the Argus Range.

|

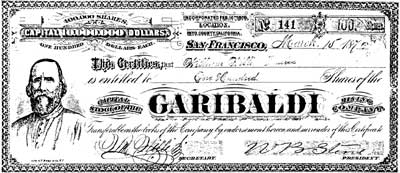

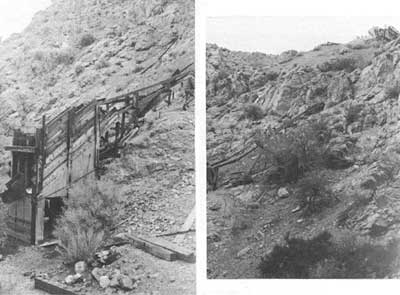

| Illustration 125. View of prospects and working area looking northeast, Wildrose Antimonium Group of Mines. Photo by John A. Latschar, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 126. Wooden platform site, Wildrose Antimonium Group of Mines. Photo by John A. Latschar, 1978. |

Although new uses had been found for antimony during the war years, such as in matchheads and in the smear on matchboxes, the market continued unsteady and the prices paid for ore subject to considerable fluctuation, making only high-grade deposits economically feasible to mine. The threat of overproduction and a consequent lowering of prices prohibited much development of lower-grade deposits such as the Wildrose ones, which contained only a few high-grade pods and pockets. Because the deposits are widely scattered and no single one is large enough to be mined profitably, because low-cost methods of treating such low-grade ore are necessary, and because of the high cost of transportation, the ruggedness of the area, and the lack of a large water supply nearby, the deposits could never be profitably mined at the prevailing market prices, except for small tonnages of high-grade ore that could be handsorted. During the war years, 1915 to 1918, the average price for metallic antimony was 22.06¢/lb., and from 1919 to 1938 it was 9.97¢/lb. Mines in the Wildrose area could only be economically viable if prices ranged between 16-2/3¢ and 33-1/3¢/lb. [69]

The concrete foundations about one-half mile south of the junction of the gravel Wildrose Canyon Road and the dirt road to the mines, which were tentatively proposed by the LCS crew as the remains of the reduction plant built about 1915, were identified by the Wildrose ranger as the ruins of a communications relay building instead, probably of the relay station shown on the USGS 1972 topographic map of Death Valley. Field crews from the Western Archeological Center have located two sets of ruins in Wildrose Canyon not inspected by this writer. One of them sounds as if it might be the ruins of the reduction furnace.

The Wildrose Antimonium Group of Mines consists of four patented properties--the Monarch, Combination, and Monopoly claims on the south side of Wildrose Canyon, and the Kennedy Quartz Claim on the north side. In addition, there are several individual deposits and prospects located near the first group. The Monarch deposit, referred to as the Wildrose antimony Mine, appears to have been the site of the most concentrated mining efforts in the area and contains the most extensive workings. The precise discovery date of the Wildrose Canyon antimony mines is unknown, but on the basis of information acquired during this study, it is the writer's opinion that the first claim formally staked within the boundaries of the present national monument was in the vicinity of the present Wildrose Canyon Antimony Mine. Because of its early discovery date and its association with Dr. S.C. George, who played an instrumental part in the -early exploration and mining history of the Death Valley region during the 1800s, and because it was the more productive of the two areas mined for antimony within the monument, the site is considered eligible for nomination to the National Register as being of local significance.

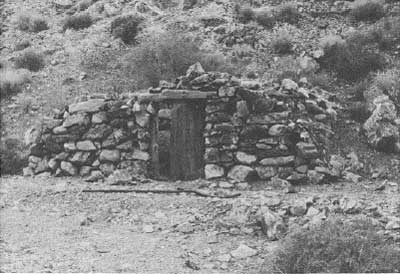

(2) Wildrose Spring Cave House

(a) History

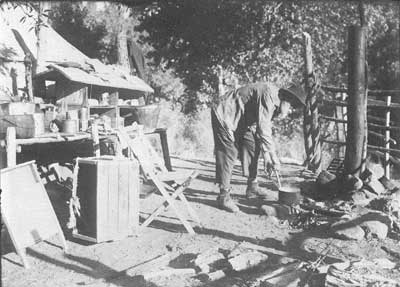

Wildrose Spring, located on the Wild rose Canyon Road about 1 miles south of its junction with the turnoff to the Wildrose Ranger Station, was long a popular campsite and meeting place for the Death Valley Shoshone, who traveled seasonally in search of pinyon nuts from the floor of Death Valley to the upper Wildrose area via Death Valley Canyon on the east' slope of the Panamint Range. [70] It may be safely assumed that roving travelers and prospectors camped at the spring from the time of earliest mineral explorations in the region. When the Wildrose charcoal kilns were producing for the Modoc Mine, Wildrose Spring would have been a natural rest stop for the burro teams hauling the charcoal west. Pete Aguereberry, Shorty Harris, and others frequently camped there in travels between Harrisburg and Ballarat in the early 1900s. While Skidoo's mining operations flourished between 1906 and 1917, the Wildrose stage stop existed less than one-quarter mile further south, consisting of a station, corral, blacksmith shop, and other outbuildings.

Dates of occupation for the Wildrose Spring cave house could not be definitely ascertained. Allusions to similar structures in the area were found, however: a 1904 water location for "Lower Emigrant Spring" mentioned that the spring was situated "on down canyon about half mile from cave house in Wild Rose Mining District on road to Death Valley"; [71] Burr Belden, in relating the experiences of Shorty Borden in Death Valley, recounts that he "arrived in Death Valley early in the 1920's and put blankets down in an Emigrant Canyon cave which he enlarged, fitting the opening with a door and window." [72] Both these references, however, appear descriptive of a structure or structures further north in upper Emigrant Canyon.

Frederick Clark, who drove a stage between Ballarat and Skidoo in 1910, said that he changed horses at Wildrose Stage Station, "which was located about a quarter of a mile down the canyon from the old Kennedy-Grundy place, now removed from the present highway." [73] The distance given here corresponds perfectly to the location of the cave house and a nearby platform site. The two men mentioned were associated with antimony mines in the Wildrose area during this time period and certainly might have had some sort of shelter or home here. In 1915 Wildrose Spring was described as a "much-used camping place on the road to Death Valley by way of Emigrant Springs. The water is very good and the supply is plentiful." [74]

Edna Perkins, during her journey through Death Valley in the 1920s, met a small group of cowboys driving cattle to a feeding ground in Wildrose Canyon. The impression she gives is that they were heading for a spring near the charcoal kilns, but upon reaching Wildrose she and her companions found the cattle and also a two-room stone shack with an iron roof near "the spring at Wild Rose." [75]

(b) Present Status

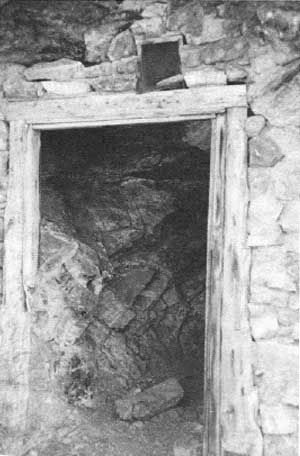

The Wildrose Spring cave house is hewn out of the cliff on the east side of the Wildrose Canyon Road on the edge of the wash near the spring. Its timber-framed door is shored up and strengthened by a surrounding masonry wall. The room itself measures about six by fifteen feet and is spanned by timbers. A small screen vent has been placed above the doorway. About 200 feet north of the cave entrance and also along the edge of the wash is a level platform site supported by a stone retaining wall. The possibility exists that this was associated with the cave in some way. [76]

|

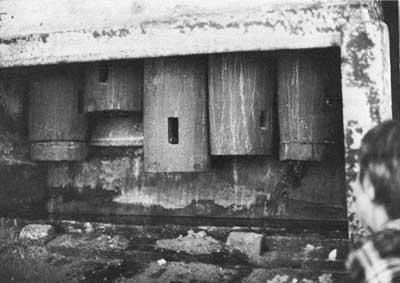

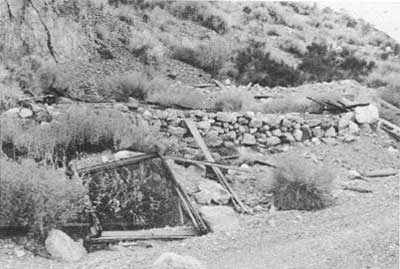

| Illustration 127. Closeup of entrance to Wildrose Spring cave house, showing interior wall. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 128. Wildrose Spring cave house entrance. Note possible leveled building site on hillside to left of cave. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

Too little data has been found on the Wildrose Spring cave house to either determine its purpose or imbue it with any historical significance. It is possible that it dates to at least the early 1900s when this route between the Panamint Valley and the Emigrant section was heavily utilized by stage and foot travel. Whether it was originally, designed as a cool and protected temporary home or camping spot, or whether it served as a cold-storage vault or spring house for a residence or store of some kind on the nearby platform site is unknown. Nonetheless, the cave is an interesting resource and a policy of benign neglect is recommended.

(3) A Canyon Mine

(a) History

This site was not visited by the writer in 1978, but was inspected by Bill Tweed and Ken Keane in connection with the LCS survey in 1975. The area was once accessible either via a 2-1/4-mile-long unimproved dirt road leading east down A Canyon from the Emigrant Canyon Road and eventually turning into a foot trail necessitating a 1-1/4-mile-long hike to the mine workings, or by following about a one-mile-long dirt road leading north from the Wildrose Canyon Road about 2-3/4 mites east of Wildrose Ranger Station. This latter route led to a corrugated-metal structure undoubtedly connected with the mine workings, which are one-half mile further north on the ridge along a foot trail. In later years a bulldozer road was pushed north up the ridge from Wildrose Canyon over to the mine and on over the ridge down into the head of A Canyon. All these routes were heavily washed during flash floods in September 1975, making the site accessible only by foot.

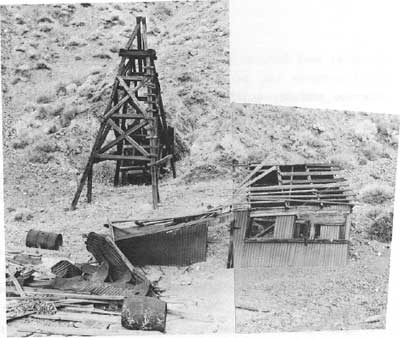

The mine workings themselves consisted of a solid wooden headframe standing over a wood-lined shaft. A collapsed wood frame tool shed and blacksmith shop, roofed with corrugated metal and built on the dump near the shaft, had partially collapsed by 1975. A good-sized brick forge was still located inside the building. Bulldozer prospecting was evident in the general vicinity of the mine.

The only mention found of early activity in the area is a notation mentioning the discovery by Reno men of high-grade silver ore in A Canyon reputedly running up to 2,500 ozs. in silver. [77]

(b) Present Status

The current appearance of the site is unknown.

|

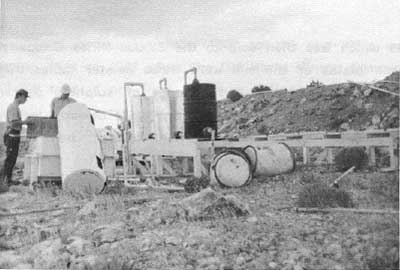

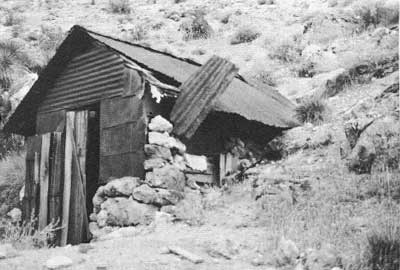

| Illustration 129. Headframe and tool shed, A Canyon Mine. Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

|

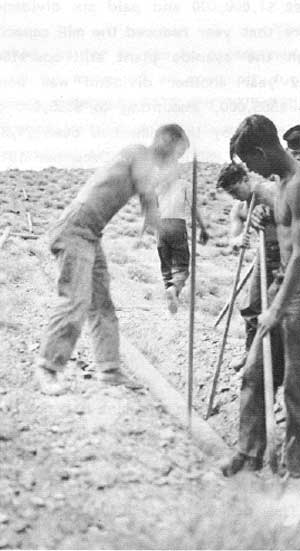

| Illustration 130. Forge inside tool shed, A Canyon Mine. Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

The LCS crew determined that this site was probably a 1920s to 1930s operation. The only structures on site of any particular interest were the headframe and the timbered inclined shaft, both being solidly reinforced and in relatively good condition. On the basis of current data, this site has no significance in the history of mining in Death Valley. Benign neglect is recommended.

(4) Nemo Canyon Mines

(a) History

Mining activity in the Nemo Canyon area was contemporary with mineral development at Skidoo and Harrisburg. The only claims in this area of which specific mention was found are the Eureka Nos. 1, 2, and 3, located 10 April 1908 by Judge Frank G. Thisse of Skidoo and situated in Nemo Canyon about 1,500 feet east of the Skidoo pipeline. [78] Judge Thisse returned to Skidoo in April 1908 to have samples of his ore assayed; the results were so encouraging that a small rush ensued to the discovery site. James Arnold, general manager of the Skidoo Trading Company, was in partnership with Thisse, and proceeded with a wagonload of supplies to the area with intentions of setting up a camp. Because of its proximity to the pipeline and its location within one-half mile of the wagon road, it was assumed that the mine would be easy and cheap to work and profitable to develop. With visions of the birth of a new bonanza camp, many people descended on the area within a short time from Harrisburg and other surrounding communities. The extent of development activity at other mines in the canyon is unknown, although there were notices of more strikes in the ensuing months. [79]

Frank Thisse's original find evidently later became known as the Nemo Mine and was referred to in August 1908 as a profitable gold- and silver-producing venture whose silver samples were assaying over 2,000 ozs. of silver and 1 oz. of gold per ton. Although still owned by Thisse and associates of Skidoo, the property was under lease to S.E. Ball and partners (later connected with the Tucki Mine) who were extracting and shipping ore averaging around $300 per ton. [80] Another large strike was reported in Nemo Canyon during the winter of 1908, with assays yielding over $200 in gold and 86 ozs. of silver per ton. The area was at this time evidently judged to have some promising production potential, because word was soon being spread by none other than Shorty Harris that a ten-stamp mill was to be erected. [81]

The eleven claims comprising the Nemo Mine were leased by George Cook and Joe Wosnieck about three weeks later, and ore was soon uncovered assaying up to $3,300 a ton in silver. The site was being touted as "one of the very best silver properties in the county. [82] Prospective purchasers Wingfield and Scott, of Goldfield fame, and Bob Montgomery of Skidoo, had examined the claims, whose purchase price was set at $50,000 by Thisse and J.R. Mason, the co-owners. In addition Cook and Wosnieck were demanding $20,000 for their interests, making a total of $70,000, a sum not considered exorbitant for a property on which there was indication of a deeper, richer, and more permanent ore body yet to be developed. [83] At this time the site consisted of both surface and underground workings.

The Goldfield capitalists evidently decided not to invest in the promising mine, possibly deciding the asking price was a bit steep. Whatever the reason, Cook and Wosnieck continued to operate their lease, happily discovering that the ore body grew larger with depth, and by January 1909 they had assembled 300 tons of silver for shipment to the Four Metals Company smelter in Keeler. An experimental consignment of three tons was sent there by wagon in February, with values ranging from $600 to $700 a ton. Because the smelter could not assure treatment before two or three weeks, the ore was then shipped to Hazen, Nevada, for processing. [84]

Another strike in Nemo Canyon was announced in March 1909 by a brother of Bob Montgomery (owner of the Skidoo Mine) who reportedly found silver ore assaying 2,800 ozs. in silver and 4 ozs. in gold per ton. Meanwhile the Cook lease on the Nemo Mine was still yielding a great quantity of high-grade ore, worth over $300 per ton. Five outfits were now operating in Nemo Canyon and in Wood Canyon immediately to the north, most being company ventures, with some leasing activity. [85]

From 1909 to 1920 there is a noticeable dearth of information about mines in Nemo Canyon, indicating that despite its spectacular early production record during the short period from the spring of 1908 to the spring of 1909, the area never attracted much investment capital. In January 1920 notice appeared that a certain J.J. King was leaving Independence for Nemo Canyon to check up on some mining claims he owned there. S.E. Ball, who had held a lease on the Nemo Mine property in 1908, was still working a silver claim in Nemo Canyon in 1922, and had reportedly removed ore worth $10,000 from the mine through the years. [86] This might refer to the Grey Eagle lode mining claim in Nemo Canyon, one-third interest in which was transferred by Ball and Ed Attaway to Maude E. Attaway in 1924. [87]

During the mid-1930s Walter M. Hoover and a man named Starr were mining in the area and processing the ore in a small cyanide plant north of Journigan's Mill. In 1938 the Journal of Mines and Geology listed a Nemo Canyon Antimony Mine, comprising six claims at an elevation of 5,000 to 6,000 feet. Owned by a Death Valley Junction resident, the mine's limited development involved only open cuts and some shallow shafts. [88] The names of two claims in the Nemo Canyon area were found in the monument files. The Nemo Gold Claims, thirteen in number, were the result of fraudulent promotions by the Blue Chip Mining Company. The Nemo Chief, two gold claims with no production record, served only as the home of an itinerant miner. By 1971 Omar L. Heironimus, owner of the Nemo Silver Corporation of Beatty, Nevada, acquired the water rights to a spring near the Journigan Mill site, and was leasing the property with the intention of cyaniding the tailings dump there. By this means it was hoped to acquire enough capital to mine Heironimus's gold and silver properties in Nemo Canyon. [89]

|

| Illustration 131. Building site in foreground and prospecting activity along hillside in back, Moonlight claims. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 132. Nemo #1 Mine, later relocated as Christmas Mine. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

(b) Present Status

Adjacent to the road to the Christmas Mine, on the south side and about one mile east of the Wildrose Canyon road, is a site marked by a Mine Hazard Area" sign. No structures remain, but it is assumed from the burned boards and assorted metal refuse on the ground that at least one wooden building once stood here. Purple glass has been found in the area. In the hills immediately to the south are some adits and prospect holes that were not visited by the writer--mining activity appeared to be minimal.

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

Mineral development in Nemo Canyon, beginning' about 1908, appears to have been of relatively short and discontinuous duration, never sustaining such large-scale activity as found at Harrisburg or Skidoo. The largest operation in the vicinity was apparently the Nemo Mine. Its notice of location placed it slightly over one-quarter mile east of the Skidoo pipeline, which passed through the camp at the site labelled "Christmas Mine" on the USGS Emigrant 'Canyon quadrangle map and continued south. It therefore seems plausible that the Nemo Mine, referred to in the 1930s as the Nemo Canyon Antimony Mine, was the earliest location of what later became the Nemo #1 Mine operated by Omar Heironimus and a man named Mondell. This property, on a hillside south of the "Christmas Mine" at about 6,000 feet elevation, was relocated by Ralph Pray in 1974 as the Christmas Mine. It will be discussed in the following section. The site located a mile east of the Wildrose Canyon Road and designated by three adits on the USGS Emigrant Canyon quad contains the Moonlight claims, owned. originally by Heironimus and later also relocated by Pray. (A 15 April 1927 article in the Mining Journal, p. 29, mentions the Moonlight Group of seven claims in the Wild Rose Mining District, recently acquired by Long Beach, California, investors for $755,000.) None of the mining sites in Nemo Canyon meets the criteria of evaluation for associative significance necessary for nomination to the National Register.

End of Volume I, Part 1

Beginning of Volume I, Part 2

(5) Christmas (Gift) Mine

(a) History

A Christmas (or Christmas Gift) Mine antimony lode was reportedly discovered by Dr. S.G. George on Christmas Day 1860, during George's unsuccessful second attempt to locate the lost Gunsight lead. [90] Earlier that year he had headed a contingent that joined forces with the New World Mining and Exploration Company from San Francisco, headed by Col. H.P. Russ, and together they had entered Owens Valley. George and a detachment had separated from the main body here and headed east, discovering promising ledges in the rugged Panamints and organizing the Telescope Mining District. Returning to San Francisco, some unscrupulous people involved in these discoveries managed to secure investment capital there that would, they assured, be sunk into development of the Telescope District mines. Instead, most of these con artists left town with the monies; none of the original discoveries were actually placed on the market, nor were any of the companies formed to work. the Telescope mines legitimate.

Late in 1860 the George party made another trip out from Visalia, California, into the Death Valley country, resulting in discovery of a Christmas Gift Mine on December 25. Not having the necessary equipment to work the mine, and because winter was at hand and snow was already falling, the expedition started home. The following year W.T. Henderson and three others began work on a 150-foot tunnel to tap the Christmas ledge, but they were eventually driven out by unfriendly Indians. [91]

It is the writer's opinion, due to personal research findings and discussions with others familiar with mining activity in this section, that the so-called Christmas lode discovered by Dr. George is not the Christmas Mine found on the USGS Emigrant Canyon quad, but is instead what is today known as the Wildrose Canyon Antimony Mine southeast of the Wildrose Ranger Station. On the basis of data procured it appears that the workings found at what is presently labelled the Christmas Mine were first excavated in connection with work in Nemo Canyon in the early 1900s. As mentioned in the Nemo Canyon section, one of the present Christmas Mine sites is a relocation of the Nemo #1 Mine. In 1906 labor was performed in this area by the Christmas Mining Company under E.F. Schooley. Notice was found in 1908 that a Dan McLeod held a two-year lease on the Christmas Gift in the Panamint Range, "probably the oldest known mine in the county," on which he intended to install a twenty-horsepower gasoline hoist. The most recent owner of this property has been the Keystone Canyon Mining Company of Pasadena, California, Ralph E. Pray, president. [92]

In researching the Christmas Mine it is easy to become confused initially by references to the productive and more developed Christmas Gift Mine that was part of the Mackenzie Group (including the Pluto and Lucky Jim) four miles north of Darwin. This was a silver-lead mine being worked at least by 1890 and through 1948. [93]

(b) Present Status

The area designated Christmas Mine on the USGS Emigrant Canyon quad consists of two sites and is reached via dirt road leading east from the Emigrant Canyon Road about 4-1/4 miles south of Emigrant Pass. The mine camp is about 1-3/4 miles east of the Emigrant Canyon Road; the only extant building there is a small wood and corrugated-metal shack. The cabin is posted "Property of Christmas Mining Co." and contains only some bedsprings and chairs. Also on-site are a tin-sided pit toilet and two building sites southwest of the cabin. Nothing remains on them now but piled lumber and an old refrigerator. The burned ruins of a dugout can be found, consisting of a shallow hole filled with metal scraps. Northwest of the privy is a stone masonry support that once carried a portion of the Skidoo pipeline across a wash. The support is fifteen feet long, four feet wide, and two feet high. The pipeline scar is visible continuing on up over the hills to the southwest. Continuing east from the residential area on a four-wheel-drive road one arrives after one-half mile at the scene of some prospecting activity. Not much is left on site. Near the road is the ruin of a collapsed dugout or timbered adit, with beams visible protruding from the rubble. On west, around the top of the hill, are a caved-in stope and the remains of a timbered shaft. Much metal refuse lies around, but there are no building remains.

|

| Illustration 133. Christmas Mine residential area, view to east-northeast. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 134. Caved-in shaft at prospect site due east of residential area. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 135. Masonry support for Skidoo pipeline, near Christmas Mine camp. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

A dirt road south from the residential area leads to a more complex mining operation, the Nemo #1 Mine that was relocated as the Christmas Mine by Ralph Pray in 1974. Remains on site consist of an ore bin, rails, trestle bents, and several small shafts, one of which was framed and timbered with pinyon pine logs, testifying to the longevity of mining operations here. Three of the shafts appeared to have been operated by means of hand winches. In 1975 some prospecting work was still being carried out in the tunnels. [94]

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

A history of mining activities within Nemo Canyon may. be found in an earlier section. Although the spot labelled Christmas Mine on the USGS Emigrant Canyon quad map has been thought of as the site of the first claim staked within the present monument boundaries, it is fairly certain that George's early discovery was actually made further south. Sporadic attempts to work this Christmas Mine all the way up through the 1970s have been made, with its largest production during World War I. Exact output figures have not been found, however. [95]

The remains at both this site and at the. Christmas Mine immediately south are a strong mixture of old and new, and it is difficult to determine which workings were the result of the earliest mining activity. The discovery of rounded pinyon pine log framing in the shaft at the second site indicates that this operation was underway early, with the ore bin and rail system being later additions. This site is not eligible for National Register status due to a lack of importance in Death Valley mining history. Purple glass on the residential site further north suggests an earlier occupancy than indicated by the miner's shack standing there today. Dating the workings at the Christmas Mine prospect site near the cabin is almost impossible because of the lack of physical evidence. These last two sites are not deemed eligible for nomination to the National Register due to a lack of integrity and associative significance. The Skidoo pipeline support near the mine camp will be included within the route of the pipeline on the revised Skidoo Historic District National Register form.

|

| Illustration 136. Shaft lined with pinyon pine logs, Christmas Mine (formerly Nemo #1). Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

|

| Illustration 137. Open stope at Christmas Mine (formerly Nemo #1). Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

(6) Bald Peak Mine

(a) History

This site, located about 1-1/2 miles northwest of Bald Peak, was not visited by this writer, both because of its inaccessibility and because it had been inspected by two members of the LCS survey crew, Bill Tweed and Ken Keane, in December 1975. The area is reached via a dirt road leading east for 2-1/2 miles from the Emigrant Canyon Road about 1-1/2 miles south of Emigrant Pass. This access was reportedly badly damaged by heavy rains in the fall of 1975.

The site appeared to Tweed and Keane to be a talc operation, dating from perhaps the 1940s or 1950s. On-site was a wooden-framed building with corrugated-metal walls and roof standing on a level platform area that was supported by a corrugated-metal retaining wall. A short distance further southeast up the canyon was a good-sized one-chute ore bin; the mine workings were located on top of the steep slope behind. [96]

|

| Illustration 138. Corrugated-metal cabin at mine 1-1/2 miles northwest of Bald Peak. Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

|

| Illustration 139. Ore bin at Bald Peak mine. Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

(b) Present Status

The present condition of the mine structures is unknown.

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

This site, probably a post-Depression Era talc operation, lacks National Register eligibility. The scarcity of data on the mine suggests little production and associative connection with any of the more important miners or mining companies that operated in Death Valley.

(7) Argenta Mine

(a) History

The earliest reference to an Argenta Mine, albeit an ambiguous one, was an 1875 notice that "Argenta" was the new name being given to the Jupiter Mine owned by the Parker company, evidently located somewhere in the Panamint region. [97] It is highly unlikely, however, that the Argenta Mine near Harrisburg was ever worked this early.

As far as can be determined, this latter mine was first located in 1924, was operated by the Rainbow Mining Company in 1925, and then by the Southwestern Lead Corporation from 1927 to 1928. In 1927 notice of the mine appeared in the Inyo Independent when the Argenta Nos. 1-12 mining claims in the Wild Rose District were deeded first from Ed L. and Hazel Wright of Los Angeles to Charles W. Stanley, and then by him and his wife, Lulu G., also of Los Angeles, to the Southwestern Lead Corporation of Delaware. At the same time an Alonzo and Martha E. Stewart of Los Angeles deeded the Argenta Group (Argenta, Leadfield, and Woodside mining claims) for $5,000 to Southwestern Lead Corporation. A bit confusing is a later notice of the transfer of deeds to the Argenta, Leadfield, and Woodside mining claims for $2,000 from a D.M. Driscoll of Los Angeles to the same Alonzo Stewart. Theoretically, this should have preceded Stewart's transfer of ownership to Southwestern Lead. [98]

Around 1930 George G. Greist, evidently an employee of the lead company, filed suit against C.W. Stanley and the Southwestern Lead Corporation in lieu of unpaid wages. A Decree of Foreclosure and Order of Sale were instituted against the company in May of that year for $3,699.85, and the Argenta, Leadfield, Woodside, Thanksgiving, and Argenta Nos. 1-12 mining claims were offered for sale. [99] The litigation resulted in Greist becoming the new owner, relocating the property as nine silver-lead claims. This gentleman, referred to as a one-time sheriff of the Panamints, was indicated as living at the mine in 1933 and being a neighbor of Pete Aguereberry. [100]

|

| Illustration 140. Argenta Mine. View to southwest of main street of mine camp, February 1969. Photo by Chief Ranger Homer Leach, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

| Illustration 141. Argenta Mine camp, view to west-northwest showing bunkhouses and upper mining level, February 1969. Photo by Chief Ranger Homer Leach, courtesy of DEVA NM. |

In 1943 the property was owned by Greist and an Ed L. Wright and was under lease to H.T. Kaplin and Sam Nastor of Los Angeles, with Greist superintending the operation. Development at this time consisted of a 30-foot shaft on top of the ridge and a 630-foot adit with lateral workings and a crosscut. Ore assaying 17% zinc had also been found in an open cut south, of the shaft. The average grade of ore shipped contained 12% zinc, 5% lead, 2.80 ozs. silver, and .08 oz. gold. Seventy tons of lead ore shipped assayed 27% lead and $8 per ton in gold and silver. Equipment on-site included a machine shop, an electric-light plant with a Fairbanks-Morse gas engine, an Ingersoll-Rand portable compressor, an assay office, and assorted boarding- and bunkhouses. By 1950 only George Griest was named as owner, employing two men in prospecting work at the north end of the adit.

Two other properties mentioned in Wood Canyon were the Combination Group, owned by Wilson and associates and worked in the early 1900s, and the Arnold Plunket claims to the south. [101]

(b) Present Status

The Argenta Mine is located in the Wildrose Mining District along a ridge on the north side of Wood Canyon at an elevation of about 5,500 feet. The site is about 1-1/4 miles east of the Emigrant Canyon Road via a dirt cutoff just before the canyon road crosses Emigrant Pass. The owner, George Griest, never made much of an attempt to mine here, living off public charity until the early 1960s when he became eligible for a California State old-age pension. [102]

The mine area consists of two levels of workings. Lower on the hill is the "main street," once lined on both sides with about twenty assorted small, one-room boarding and bunkhouses and with other camp necessities such as a chicken coop. All buildings are presently in a shocking state of decay due to weathering and vandalism. Most of the structures, which were built of wood, plasterboard, and corrugated metal, have completely fallen in or been pulled down. The only items of any interest are on the north side of the street, in the form of remains of a stone dugout with a wooden false front, and, just southwest of this, a round, concrete cistern built underground, appearing to have a capacity for several thousand gallons of water. In the photographs of the camp site taken in 1969 the stone dugout appears to have been located behind a large building in the center of the community that probably functioned as the cookhouse. The dugout was probably the root cellar and the cistern nearby stored the camp drinking water.

Higher and further north on the hillside is a timbered adit and the ruins of at least two other buildings, one having been a two-story frame structure on the edge of the dump, and the other a smaller one-story frame building, possibly the assay office. Only the flooring and basement level framing of the larger building remain somewhat intact; the other structure is completely destroyed.

An incredible amount of refuse is evident everywhere on the site, ranging from modern garbage to old machinery parts to vintage 1940s and 1950s car bodies, the entire site resembling a tremendous junkyard.

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

The Argenta. Mine never yielded a profitable output nor do any structures of historical significance remain on the property. The site was not an important Death Valley mining operation and is not eligible for inclusion on the National Register.

|

| Illustration 142. Argenta Mine. View to west-northwest down main street of mine camp showing almost total destruction of buildings. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 143. Argenta Mine. View to northwest of mining area showing remains of two-story building. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978 |

(8) Napoleon Mine

(a) History

The Napoleon and Napoleon Nos. 1-2 quartz claims, situated one-half mile south of Harrisburg, were located by Pete Aguereberry on 1 January 1911 and recorded on 24 January. The location date of the Napoleon No. 3 was not found in the record books, but it was probably several years later, since it was not filed for record until 14 September 1935. [103] The Napoleon No. 1 is east of the Napoleon Claim and the No. 2 is south of it. The No. 3 joined the Napoleon No. 2, but on which side is unknown. The only reference to these claims in the literature was found in Pipkin, who was evidently told by Pete that after he had done some development work on the Napoleon he leased the claim to two men who reportedly removed $35,000 in gold ore from the mine within a six-month period and then abandoned it, leaving it ruined by improper timbering and gopher holing. [104] This large a sum seems open to. question. In 1946, when Pete's estate was settled, ownership of the Napoleon Nos. 1-4 was divided among the heirs, Ambroise Aguereberry receiving an undivided one-half interest, and the other half being given equally to Joseph, Arnand [Arnaud], James Peter, Mariane, and Catherine Aguereberry. [105]

The Napoleon Group is mentioned in the Journal of Mines and Geology in 1951 as comprising four unpatented claims, the Napoleon Nos. 1-4, owned by Ambroise Aguereberry of Trona, California. Development consisted of an 80-foot-deep inclined shaft and several adits, all within an 8O0-foot radius. Most of the ore mined has been removed from three adits southwest of the shaft. During sporadic operations from 1937 to 1939 lessees had shipped fifty-five tons of gold- and silver-bearing ore to custom mills, but the operation was currently idle. [106]

|

| Illustration 144. Shaft, tram rails, and ore chute at Napoleon Mine. Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

|

| Illustration 145. Ore bin and collapsed chute southwest of main adit, Napoleon Mine. Photo courtesy of William Tweed, 1975. |

(b) Present Status

The Napoleon Mine is situated on the north side of a ridge about one mile south-southwest of the Cashier Mine workings. The site consists of two working levels--the lower containing a main adit and an ore chute, with a timbered vertical shaft between, some dry-stone retaining walls, and the remains of a mine tramway. Uphill about one-quarter mile southwest of this first complex are a second ore bin with a collapsed chute and several adit entrances. Purple glass has been found on this site.

(c) Evaluation and Recommendations

The Napoleon Mine has no significance except for its association with Pete Aguereberry, which is minimal. The writer does not recommend that it be included within the boundaries of the proposed Harrisburg Historic District. The site does not offer potential for further research or historical archeology.

(9) Harrisburg

(a) History

i) Shorty Harris and Pete Aguereberry Strike Ore on Providence Ridge

As is the case with most important events when two or more strong-minded participants are involved, the details surrounding the discovery of the first strike at Harrisburg Flats are open to controversy. The find was made by two of Death Valley's most noted mining personalities--Pete Aguereberry and Shorty Harris. The former's version of the tale is that around the first of July 1905 the two men met at Furnace Creek Ranch, by chance, and decided because of the heat of the valley to pull out for the Panamints together and do some prospecting, although Shorty was actually more interested in getting to the 4th of July celebration at Ballarat. After negotiating the old "dry trail" through Blackwater Wash, they arrived on the open plateau now known as Harrisburg Flats, about nine miles northeast of Wildrose Spring.