|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION III:

INVENTORY OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES THE WEST SIDE

A. Southern Panamints and West Side Road

1. Panamint Mining District

a) Formation and Establishment of Boundaries

The precursor of the Panamint Mining District was the Telescope District, organized in 1860 by members of the Dr. S.C. George expedition who had penetrated into the Wildrose and Panamint regions. Named for nearby Telescope Peak, this early district was located on a spur of the Panamint Range bordering Death Valley on the west. Although the mines in the area were not heavily worked in the first few years after their discovery, the late 1860s and early 1870s saw some rough beginnings of a mining industry there. An 1872 newspaper article speaks favorably of the richness and extent of the Telescope District mines, which, it states, had been located some three years earlier. The lead, silver, and gold ores were said to be comparable to those of Cerro Gordo, besides being easy to smelt because of the nearby pinyon pines and clay necessary for the reduction process. [1]

On 1 February 1873 four notices were posted in the mountains of the Panamint Range, informing the prospecting community that:

There will be held at the camp of R.C. Jacobs & Co., in Mormon Canyon at the southern end of the Panamint Mountain Range, on February 10, 1873, a miners' meeting, for the purpose of organizing a new mining district, and forming laws to govern the same. All claim owners are respectfully invited to be present at said meeting.

R. C. Jacobs

W.L. Kenneday [Kennedy]

R. Stewart [2]

The meeting was subsequently held as advertised, resulting in the formation of the Panamint Mining District. Boundaries were established as follows:

Commencing in "Windy Canyon" (a point four miles north of Telescope Peak) at a point called Flowery Springs, and running thence in an easterly direction, following the said "Windy Canyon" to the summit of the range; thence down the east side and out to the center of Death Valley; thence southerly to "Mesquit Springs," on the eastern slope of "Slate Range;" thence westerly to the summit of "Centrie Canyon," and down the same to its mouth, continuing the same course westerly to the center of "Slate Range Valley;" thence northerly to a point in "Panamint Valley" ten miles due west from "Flowery Springs;" thence easterly ten miles to the place of beginning." [3]

Laws and regulations were adopted and Robert Stewart elected recorder for a one-year term beginning 10 February 1873. The recorder's office was to be located in Surprise Valley, where most of the principal claims were found.

b) The District's Future Seems Assured

By 30 August 1873 the prospects of the new district still looked favorable:

It is represented by experts, who have visited it for speculative purposes, as being one of the very richest and most prolific districts on the Pacific Slope in silver ores. Some one hundred silver lodes have been discovered and located, which for body and richness stand, at least in the State of California, unrivalled--the lodes running from two to thirty feet in width, and assaying from $200 to $1,200 per ton of ore. [4]

Even allowing for the tendency toward excitability and gross exaggeration common to the average California mining prospector of this era, men of some experience and supposed sound judgement and caution felt that this district had distinct economic possibilities. The best route to the mines was said to be from Havilah by stage to Little Owens Lake, seventy miles away by the Havilah and Independence stage route, and from there by mule trail, "a short two day's ride of fifty-five miles." [5]

Newspaper clippings and journals of the time give some indication of the ensuing fortunes of the Panamint District. In December 1879 some Panamint miners organized the "Breyfogle" District twenty miles north of Panamint. The main lode, of the same name, produced ore assaying from around $500 to almost $4,000. [6] By the year 1881 the Inyo Consolidated Mining Company of New York, which had purchased the Garibaldi and North Star mines in the Rose Springs (Wildrose) District circa 1876, had also purchased the only mill and several promising locations in the Panamint District and were working vigorously with much success, the mines and mill having produced about $60,000 worth of ore already. [7]

c) Mining Activity Spreads in Southern Inyo County

In July 1887 valuable ores were stilt being discovered in the surrounding country, but discouraging to miners was the fact that the rich ore could not be shipped easily or speedily to market. By May 1894 the California mining news correspondent of the Engineering and Mining Journal was projecting 11a decided tendency toward a mining boom in Southern California this year. Never within 10 or 12 years has such general interest been manifested as is shown at present. There are now more new enterprises, and apparently substantial ones, than ever before. . . ." By this time a new district referred to as South Park was springing up around Red Rock and Goler canyons, with lucrative results appearing inevitable. [8] The Redlands Gold Mining Company was in business by the summer of 1894 and was enthusiastically purchasing prospects. It even erected a ten-stamp mill five miles south of Panamint Canyon, which two years later, however, was not producing much. [9] Hampering progress in this more southerly area too was its distance from a railroad and lack of wood and water.

A correspondent of the Pacific Coast Bullion made a trip to Death Valley about this time, and in addition to describing the sights and geologic wonders of the area, reported on the current mining situation. Panamint City, he said, now housed only a watchman guarding the mill and storehouses, leaving itinerant prospectors the run of the town. He went on to explain that lawsuits had closed the mines for awhile, but the litigation was now settled and eighteen claims had been recently patented; unfortunately the current price of silver was too low to work them profitably.

The correspondent remarked that few mines were being worked in the Panamints. Charles Anthony's Defiance Mine near Post Office Spring at Darwin was operating, although no mill existed on the property. The only other mining activity centered around the Redlands Gold Mining Company. Heavy transportation costs were still hindering mining in the mountains contiguous to Death Valley. [10]

The revival of a large-scale mining industry in the Panamint District in the late 1800s evidently centered around Tuber Canyon properties. In April 1897 a Mr. Donahue and others purchased property there for $15,000 preparatory to commencing exploratory work. [11] A correspondent to the Independent wrote from the new town of Ballarat in the Telescope Range in June 1897 that "the future of this camp and district as a gold mining proposition is very bright and assured." [12] The country had a good water supply, plenty of wood available on the nearby summits of the Panamint Range, and fruit could be grown in the mountains. Quail were an abundant food source. [13] Among current activities mentioned was the work in Tuber Canyon, where development and prospecting were pushing ahead vigorously, with considerable San Francisco capital being invested there. [14] The Tuber and Aurora claims were active, while in Jail Canyon the Gem and Burro groups were being worked. In Pleasant Canyon, near the old town of Panamint, the Worldbeater and other Montgomery properties had closed down until a new bigger mill nearer the mines could be bought and installed. Claims in the Mineral Hill and Redlands Canyon areas further south were showing some unrest, with many claims changing hands. The prospecting stage here had passed, and efforts were now being made to further develop those lodes whose extent and richness were becoming evident. A custom mill was sorely needed, although it was being rumored that a three-stamp mill would be moved into the vicinity soon. [15]

Other southern Inyo County mining efforts consisted of "chloriding" operations, notably in Shepherd's, Cottonwood, and Emigrant canyons, where development of the lodes was much hampered by their inaccessibility. Revenue Canyon mines on the western edge of Panamint Valley also harbored rich strikes. [16]

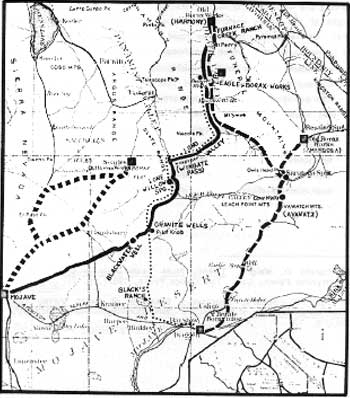

The new town of Ballarat was now the gathering place for Panamint Range miners, prospectors, and the Indian community. The Fourth of July celebration in the year 1897 was replete with "foot races, hammer and stone-throwing, burro and horse racing, giant powder salutes and a grand tug of war, in which every male inhabitant and visitor to the place, Indians included, took part, save one who from his immense size and strength was debarred from either side and officiated as referee." [17] Talks on the significance of the day entertained the visitors from almost every canyon in the evening. A stage and mail line between Ballarat and Garlock was about to commence, consisting of a single round trip weekly, to be increased to tri-weekly when cooler weather came and mining activity resumed. The main portion of the town's business and freight came through Mojave and Garlock (which evidently had the nearest custom mill, 150 miles away) because of lower freight charges and passenger fares from that direction. Although mail communication was desired through Owens Valley and Independence, the residents there were antagonistic toward facilitating this because of the camp's close communication and financial ties to the southern towns. [18]

Also in this year mention was made of construction of a Randsburg Railway from Kramer station on the Santa Fe and Pacific to Randsburg, and a possibility evidently existed of the line being projected to Salt Lake City, thus making another transcontinental route. The Los Angeles trade would be increased tenfold, it was argued, by bringing the line north into the Panamint Valley from Kramer and tapping the Searles borax fields, the Argus and Slate ranges, and all the mining camps in Redlands Canyon, Mineral Hill, Pleasant Canyon, Happy Valley, Surprise, Hall, Jail, and Tuber canyons, and the Wildrose area, not to mention the Argus, Revenue, Snow Canyon, and Modoc mines on the west side of the valley. [19]

By 1897 new placer locations had been found on the east side of the Panamints, panning $30 to $40 per day. The central Panamints were still quiet, Panamint City now containing but two residents, sole witnesses to the steady decay of the town's large stores, saloons, and billiard halls full of furniture. The only operating business was a large, fully-stocked hardware and implement store selling goods to miners at incredibly low prices. Several mills in the vicinity full of machinery were idle. [20]

By April 1898 Ballarat sported a population of nearly four hundred, at least one hundred of whom were gainfully employed. It contained substantial adobe houses and was the outfitting point for the Panamint Range, Snow Canyon, and other nearby districts. Mines were being worked near Willow Spring to the south; the Burro Mine in Jail Canyon had recently been bought, the new owner also purchasing the Redland Company's mill; the South Park mines were producing; and the Tuber Canyon mines were doing well, as were the Mineral Hill properties four miles south of Ballarat. [21]

From 1898 to 1899 freight teams left Johannesburg, sixty miles south of Ballarat in Kern County, for the Argus Range hematite iron-ore deposits, some yielding $8 a ton in gold, and for the Panamint District high-grade silver-lead ore mines. Although Johannesburg was the best outfitting point for a prospector coming to Panamint from the south, Keeler, the closest railroad stop to the Panamint Range, was more accessible for people from the north or from Nevada. [22]

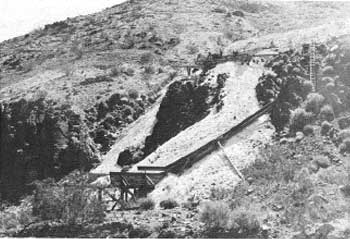

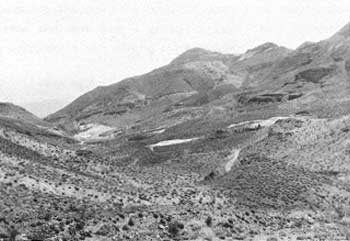

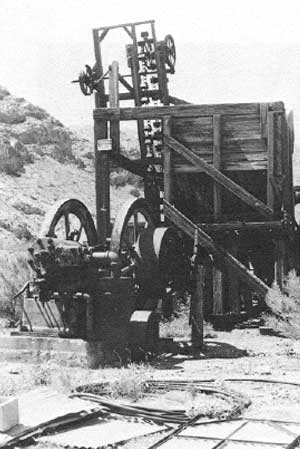

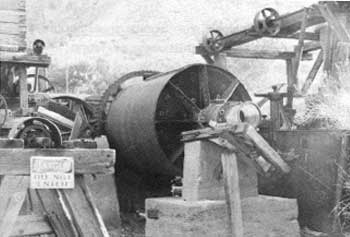

d) Interest in the Panamints Spreads to Nevada

By February 1900 the Panamint District continued strong and reported much activity. Ballarat, in the process of heavy construction, held much commercial importance in the area because of its central location arid accessibility to miners in the adjacent mountains, its good water supply, and its proximity to the railroad. Mines in the Panamints were producing ore that could be easily milled or on which cyanide treatment was effective. Principal mines in the western Panamint Range were still in Tuber, Jail, and Pleasant canyons, and at Mineral Hill. In Tuber Canyon a twenty-five-ton Bryan mill had been erected and in Jail Canyon a three-stamp mill was operating. The Radcliffe Consolidated Gold Mining Company was running a twenty-stamp mill in Pleasant Canyon, and ore was being transported from the property by tramway at low cost. [23]

By 1902 the Inyo Gold Company of Los Angeles, which owned mines in Tuber Canyon, near Panamint, and the Tuber Mine at Ballarat, was shipping in a fifty-ton cyanide plant to wash tailings from the Tuber and also ore from there. This was in addition to a six-stamp mill already on the Tuber Mine property. [24] In the early 1900s the Panamint District began attracting the attention of prospectors from the Goldfield, Nevada, area. [25] Because earlier prospectors had been intent only on silver, it was now thought that vast amounts of gold probably remained. Geologically, the southernmost part of the range seemed to be similar to the Tonopah, Goldfield, and Bullfrog districts, and good opportunities were imagined to exist for those who took the time to look.

Jail Canyon was still the best producer in the Panamints, boasting the Gem Group and rich Burro Mine. In Surprise Canyon, Jack Curran had located some good gold claims near Panamint City. The Radcliffe Group in Pleasant Canyon was still producing, as was the World Beater just above it. Coyote Canyon, between Goler and Redlands, was the location of a great strike showing ore of a high assay value, more than $35, some shoots running up to $125 and $230 per ton. Prospects looked good further south except for a lack of capital. [26] New locations were constantly being made, though, since water and wood were plentiful. Several companies were already operating in the Redlands area and it was thought that summer and fall would bring an influx of desert prospectors.

By autumn the entry of prospectors from the Tonopah, Goldfield, and Bullfrog fields into the Panamint region seemed even more imminent, despite the region's isolation from railroad transportation facilities and roads, which cast doubt on the success of every mining venture. But because remote areas of Nevada were proving to be profitable, new hope was seen for the Panamint area, especially because these prospectors from Nevada were familiar with the problems and frustrations of desert mining. [27]

In the meantime the original Panamint Mine seemed slated for a comeback. An October 1905 newspaper article stated that Jack Curran, the "King of the Panamints," had relocated the old mine, which it reported was at one time bonded for $5,000 to an English syndicate. Some later history of the once-roaring silver camp was presented, although some facts, such as those regarding population figures, are open to question. The article reported that $700,000 was spent developing the old mine (improvements, wages, etc.). Currently remains of the twenty-stamp mill, saloons, and stone warehouses could still be seen. The canyon was deserted, the article continued, when silver, once selling for $1.29, was demonetized, and the lack of good transportation facilities in addition made mining in the area unprofitable. After the camp was deserted, the owners of the mine fell into dissension over some matter. The workmen were not paid, and in retaliation took over possession of the property, which they worked until they received due compensation. After setting fire to some of the buildings, they scattered, and the town was left to the elements. [28]

Several more well-known prospects were appearing in the Panamints at this time in Hall Canyon, such as the Pine Tree Mizpah and the Valley View, and prospecting was becoming a much more organized and systematic business. A party of four men from Goldfield came into the Panamint Range in November 1905 equipped with fourteen burros, an elaborate camp outfit, and a determination to cover as large a territory in as short a time as possible. The head of the party, who also held interests in Colorado mines, stated that in the Panamints he saw the same class of ore as at Leadville, but of higher grade. Colorado investors, he allowed, were very interested in the value of ores that could be found here. [29]

During the early 1900s mining in the Panamint section was booming: mineral resources were good, geological conditions promising, new mining camps were being established nearby at Greenwater, and at Emigrant Spring, Harrisburg, and Skidoo, and Nevada mining men were now investing large sums in the Panamint region. Full forces of men were at work, reminding people of the early days of Tonopah and Goldfield. The new camp of "Panamini," mentioned earlier, was predicted to be one of the most prosperous of western mining camps, with water being piped a mile and a half to supply all needs. [30]

Mining was not easy for men in this region, as evidenced by the statement of a mining engineer in 1906 that the bodies of eight prospectors who had died from heat stroke in the Panamints were brought in during his stay. The average temperature for several days was 116°F., even at midnight, while the thermometer would rise to 135°F. by noontime. In contrast, by the first of March 1907 Skidoo and Ballarat were buried in deep snow. Other problems existed in addition to vagaries of the weather, one group of prospectors reporting a difficulty centering around settlers in the Panamint Valley who staked and restaked mining claims, but never worked them, effectively preventing their exploration by bona fide mining men. [31]

The price of silver in 1907 was holding steady, running around 75¢ in New York, as high as it had been for several years. Locations were still being made at this time around old Panamint City. While another new "Panamint" was in the throes of birth just across the mountains in Johnson Canyon, miners arriving to work there were also crossing over to the old townsite and staking claims in this still-mineral-rich area. The finding of high-grade silver ore was mandatory in order to realize a profit because of transportation problems. One miner locating here reported sixteen patented locations around the old mill site, where a dozen vacant buildings were left from the boom days. [32]

e) Consistent Production Continues into Late 1900s

For the next few years mining continued in southern Inyo County on a profitable scale. At Cerro Gordo, Darwin, and other places on the west side of the Panamints steady ore production was maintained. By 1912 the Panamint Mine had been purchased by Al Meyers of Goldfield-Mohawk fame, the property's productive record having reportedly been two to three million dollars. The mine had been idle since 1893, but rehabilitation work was to commence immediately; the ore was to be shipped to Randsburg, the nearest railroad point, seventy miles away.

A summary of Panamint Range mining activity in the early 1920s appeared in the Inyo Independent Most operations in the section were concentrated on the western slope, except for the Carbonate silver-lead mine on the east edge and small gold mines at Anvil Spring in Butte Valley. The Trona Railroad and American Magnesium Company's monorail system were ameliorating somewhat the transportation and isolation problems that had existed in the area for such a long time.

Producing properties were located in Goler Canyon (Admiral Group, Shurlock, Gold Spur); South Park Canyon (Gibraltar); Hall Canyon (Horn Spoon); Jail Canyon (Gem Group, Burro Mine); and Tuber Canyon (Salvage Mine and mill, Sure Thing Group). The Pleasant Canyon mines (World Beater, Radcliffe, and Anthony mines) were now all idle. The Panamint Mine under Myers's ownership was being resurrected by modern mining and milling equipment. [33] The Panamint Mining Company determined at this time to construct a stone and gravel toll road beginning at Surprise Canyon and climbing east 5-1/2 miles to the old Panamint City site. The purpose of the toll was to get revenue from miners in that area to assist in road maintenance, and as such was a venture similar to the later Eichbaum toll road built further north a few years later. [34]

All along the Panamints refinements in technique were expected to finally make the old silver-lead deposits below the 200-foot level pay. By the early 1930s silver was expected to stabilize at a high market figure, and the mining community eagerly anticipated great things for the Panamint Valley and environs. In the mid-1930s Tuber and Jail canyon mines were operating on a large scale, the development of mines in Pleasant Canyon was being well financed, and Goler Wash, now more accessible, was being explored. No big strikes were made during the late 1920s and early 1930s, but prospectors kept combing the hills and earlier operations kept producing. [35]

Leasers and owners both were working in the Ballarat District by the late 1930s, and the consensus of opinion was that "taken as a whole the Panamint Range, while not spectacular, is a consistent [sic] producer, an estimated 5000 tons having been shipped from there during the present year." [36] The diversified resources of Inyo County were just now starting to be fully realized, and companies such as Sierra Talc and the Pacific Coast Talc Co. were involved in development work in the Darwin district. This somewhat offset losses in lead and silver mining in the area, whose condition was stagnant due to the low market price of these particular metals. Despite this, it was concluded by mining officials in the county that "the mining industry in southern Inyo seems to be thriving at the present time. It has as always many difficulties to contend with, especially in the gold producing districts. The greatest need there is milling facilities closer to the properties. It should be borne in mind that the shortest mine to mill [route] established in the immediate vicinity, (and] a program of more and better improved roads would be the greatest single factor toward increased prosperity of the miner and thereby of our whole county. [37]

Overall, production levels reached now seemed to stabilize due to increased values in market prices, newer machinery, and improved roads and processes. On through the 1940s and 1950s the Darwin District, Tecopa District, and Modoc and Slate Range regions continued to produce steadily. The Panamint mines were leased in 1947-48 by the American Silver Corporation, which performed some work on them. The properties that originally initiated exploratory work in the area--the Alabama, Hemlock, East Hemlock, and High Silver patented claims, and the unpatented East Hemlock and High Silver mill sites--were privately owned, as were the Challenge, Comstock, Eureka, Hudson River, Marvel, Stewart's Wonder, Wyoming, Star, Little Chief, Independence, Ida, and Panamint Central patented claims, and Stewart's Wonder, Challenge, Little Chief, and Wyoming patented mill sites, plus four other unpatented claims, but all were idle. [38] Tungsten was later found on the Stewart's Wonder, Challenge, and other claims in the Panamint mines complex, and soon a strong resurgence of interest in the Panamint Range centered around this strategic mineral. The renewed interest was attributable to some price stability occurring as a result of the federal government's stockpile sales policy and to the absence of tungsten imports from mainland China. [39] Exploration in this new field was short-lived, however, as it proved to be further north on Harrisburg Flats.

f) Impact of Panamint and Other Early Mining Districts on Southern Inyo and Death Valley History

The mining districts west of Death Valley have played an important and productive role in Inyo County's economic and social history, and are worth further study on their own. What is important, and what has hopefully been transmitted in this short chapter, is a realization of the extreme and lasting influences exerted by these early communities and their inhabitants on the later mining progress of southern Inyo County, including especially that of Death Valley. The amount of territory covered by Owens and Panamint valley prospectors, and by businessmen on the lookout for a promising investment, was phenomenal, especially in light of the dearth of transportation facilities available at the time. These peregrinations were the primary means by which men in the Death Valley camps and in the Nevada fields further east were kept apprized of mining conditions in surrounding areas and the methods most successfully used in extracting ore. The exploitation of these western mining districts has been at times energetic, at times frenzied, and always sporadic. By dint of much persistence and experimentation, however, the groundwork was laid here for the more systematic and technologically sound methods that ultimately produced such gratifying results in later mining operations in the southern Panamint, Wildrose, and Ubehebe sections of Death Valley during the next few years.

g) Panamint City

The first boom town of the Panamint Range was Panamint City, in an area first discovered in January 1873 by R.C. Jacobs, W.L. Kennedy, and R.B. Stewart, who located eighty or ninety claims in the vicinity. Two necessities for successful milling operations--timber and water--were plentiful near the site immediately south of Telescope Peak and about 100 miles from Independence.

As word of the strike leaked out, excitement once again prevailed in southern Inyo County. Numerous parties left immediately for the district with wagonloads of tools and provisions. Principal lodes were the Wide West, Gold Hill, Wonder, Wyoming, Marvel, Pinos Altos, Surprise, Challenge, Beauty, Chief, Cannon, Venus, King of Kayorat, Esperanza, Silver Ridge, Garry Owen, Balloon, Panamint, Mina Verde, Blue Belle, Sunset, and Pine Tree. [40] Optimism about affairs at Panamint ran high. An August 1873 edition of the Independent quoted a Lagunita, California, resident who told of the "exceedingly fair ores" being taken out of the district. "Panamint prospects are improving daily," he stated, "I think we have in this camp the most intelligent and liberally inclined miners that perhaps ever got together. [41]

To reach the Panamint Valley and the scene of the new strike, on mules or in wagons, afoot or on burros, one had to branch east from the bullion trail at Lagunita (Little Lake), about fifty-five miles distant, and follow a burro path across the Coso and Argus ranges. Jacobs, realizing that the area's development was dependent upon a good communications system, proceeded to raise funds in Los Angeles by subscription for a more convenient road going south of the mountains via what is now Searles Lake and the north end of the Slate Range. Because the future of the Panamint mines seemed promising enough at this point to warrant such investment, money was quickly raised on the West Coast, many of the businessmen there recalling the lucrative trade the city had established earlier with Cerro Gordo.

By mid-June 1874 the road was completed over the Slate Range where it connected with the Surprise Canyon section. Although this latter road was almost immediately washed out by a cloudburst, it was soon repaired and the entire route ready by mid-August 1874, whereupon Jacobs hurriedly shipped in a ten-stamp reduction mill from San Francisco to process ore from his Wonder Mine.

Earlier, around 18 December 1833, E.P. Raines, a well-known mining man and promoter, in an effort to finance the camp, journeyed to Los Angeles to enlist support for the Panamint District. An article in a Los Angeles paper of 13 December stated:

Messrs. Vanderbilt, Kennedy and Rains arrived here Wednesday from Inyo county with some very rich specimens of silver ore from the Panamint district. The specimens are exhibited at the Clarendon creating quite a little excitement, particularly among those who are unfortunately not interested in the lead. The ore is familiarly known as copper silver glance, but does not contain enough copper or other base metals to prevent it from being easily crushed. The claim is situated about sixty miles south east of Cerro Gordo and was located last January by Mr. Kennedy. It presents the most encouraging prospects and will be developed as soon as the necessary tools and machinery can be procured. It is estimated that the ore will turn out about $1,000 to the ton [42]

Raines did finally succeed in persuading Senator John P. Jones of Nevada, who had already made a fortune in the silver mines of Nevada's Comstock lode, to look into the matter in the spring of 1875; impressed, he in turn interested his fellow senator, William M. Stewart of Nevada, and other capitalists in investing in the Panamint lodes. Together they organized the Panamint Mining Company in 1875 with a capital outlay of $2,000,000. [43]

With the entry of these moguls onto the Panamint mining scene, the attention of the western mining community was safely captured. Jones's and Stewart's Surprise Valley Mill and Water Company became the area's principal business enterprise. Stewart ultimately bought up Jacobs's ten-stamp mill; the Surprise Canyon Toll Road that ran up Surprise Canyon to Panamint, built by Bart McGee and others for $30,000; a site for a twenty-stamp quartz mill; and all principal mines of the area. 44 First-class ore was shipped to England for smelting (an indication of its richness); the rest would be reduced in the projected local mill and furnace. [44]

In November 1874 a wagon road from the Owens Valley through the Coso and Argus ranges to the Panamint Valley was opened, and twice-weekly service was initiated. Later in November a second stage line brought visitors east from Indian Wells, connecting with San Francisco and the West Coast. Stages also were routed from San Bernardino and Los Angeles.

By November 1874 the population of Panamint City was close to 1,000. The main, mile-long, muddy, rutted street was lined with rubbish and tents, about fifty buildings, either frame or stone, and log or rock huts in which the hardy miners huddled for warmth. The town supported many business establishments and the usual number of saloons, all demanding exorbitant prices for goods. The Bank of Panamint was begun, a first indication of stability, and even a newspaper, the tri-weekly Panamint News printed its first issue on 26 November 1874. A cemetery was located a short distance up Sour Dough Canyon.

Senator Stewart soon made known his need for someone to export his ore and bring in machinery essential for the continuing productivity of his mills. Remi Nadeau, the French-Canadian involved in Cerro Gordo freighting, was the logical choice, but too expensive. A San Bernardino freighter was contacted, and he began hauling freight through Cajon Pass and across the Mojave Desert in October 1874, creating as a side effect a vast new business for his hometown. Realizing the profits that were daily being lost, Los Angeles teamsters entered the trade by early November, directing their teams past Indian Wells and on to Panamint. And not surprisingly, soon Remi Nadeau and his Cerro Gordo Freight Company joined in transporting the heavy flow of goods passing between Panamint City and Los Angeles. The latter truly began to share in the prosperity created by the Panamint boom, as lumber, grain, flour, and whiskey passed in large quantities to the growing camp full of thirsty men.

By December 1874, the height of Panamints career, the Surprise Valley Company operated six mines and employed 200 'miners. [45] In the middle of that month Jacobs's ten-stamp mill began production. Population of the camp was now between 1,500 and 2,000 men. A Frenchman, Edmond Leuba, deciding to visit the active town, left Los Angeles around December 1874. He constantly met people on the road going to and from Panamint, attesting to the thriving commercial activity between the two places. Unfortunately he arrived at the mouth of Surprise Canyon at nighttime and had difficulty avoiding the teamsters who were coming down the steep, narrow canyon road even at this time of day. This was a toll road, costing Leuba $3.00 for his two horses and a wagon. Three miles further east the ravine opened out and the lights from many fires were visible in the canyon. Mining blasts sounded every instant. He found a place for his horses in the shelter of a tent and lodging for himself in the dug-out cellar of a restaurant, which he shared with "a dozen figures looking more or less like candidates for the gallows." [46]

Next morning the Frenchman commented on the bright sun and intense heat of the canyon. Panamint camp, he saw, was "composed of about fifty huts made of logs, tents and little houses partly dug out of the rocks." [47] Work there progressed until January when the snow became too deep. At that time many of the miners left camp for warmer regions, and the population dwindled markedly.

|

| Illustration 6. Upper part of Panamint City, 1875. Photo courtesy of G. William Fiero, UNLV. |

Commenting on the quantity of saloons in the town, Leuba next proceeded on a guided tour of the Panamint mines, which he stated

have been very little worked as yet. The deepest shafts are not more than seventy-five feet below the surface and the tunnels showed very little development. But it is in these first workings that they have found the richest ore and that which is easiest to work. Only two mines, so far as I know, have produced good ore to a depth of five hundred to six hundred feet. There is no mill for the reduction of this ore as yet at Panamint. The richest ore is sent to San Francisco at a transportation cost of $80 to $100 a ton, while the second class ore is heaped up at the mouth of the shafts from which it is extracted, awaiting the time when it can be treated here. [48]

Leuba seemed to think the mines were daily diminishing in value, and the reduction processes becoming more and more difficult. He says this condition lasted over into the next year, when Panamint began losing people to Darwin, where lead in the deposits made reduction easier and less costly.

By the spring of 1875 full-scale production in the area was almost a reality, and toward the end of June 1875 the Surprise Valley Company's twenty-stamp mill was started up. Bullion was regularly shipped via the Cerro Gordo Freight Company's mule teams, and work for everyone was plentiful. The economic mainstays of the camp--the Wyoming and Hemlock mines--were producing heavily.

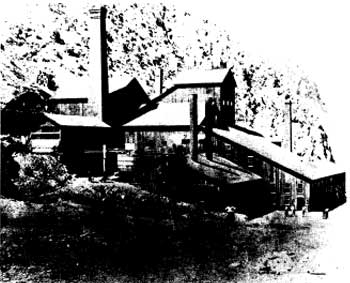

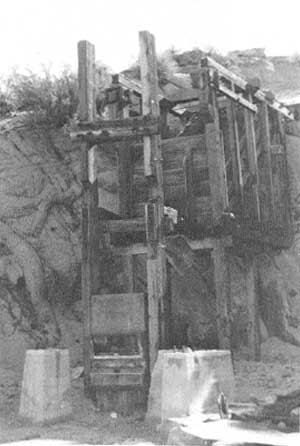

|

| Illustration 7. Jones's and Stewart's twenty-stamp mill and furnace in old Panamint City. Date unknown, but probably prior to 1877. Photo courtesy of DEVA NM. |

|

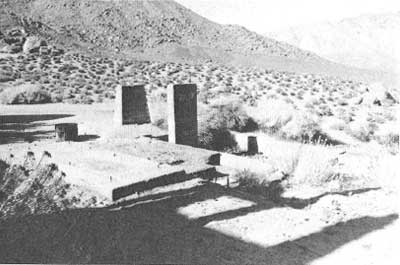

| Illustration 8. Ruins of old Panamint City smelter, date unknown. Photo courtesy of DEVA NM. |

As happens in boom towns, however, the halcyon days could not last, and by the end of 1875 the thriving era of Panamint was coming to a close. As Leuba had noticed, many miners were now heading toward Darwin and the New Coso Mining District, where it was warmer and prospects looked good for employment. The Panamint News even moved there early in November, becoming the Coso Mining News By the spring of 1876 the Wyoming and Hemlock mines were depleted.

This, in addition to other discouraging factors--no new discoveries in the area; the demonetization of silver; setbacks experienced by Jones and Stewart at their silver prospects in the Comstock lode, resulting in depletion of their financial reserves; and the impossibility of realizing a profit on refractory ores whose yield was not commensurate with their recovery cost--caused the Surprise Valley mill and mines to shut down in May 1877. Stories also circulated of "stock jobbing; of grafting and trouble among the grafters; of seizures by stockholders who were not mining men; of fortunes spent in building a mill where a smelter was needed; of consequent failure, disappointment, abandonment and complete depopulation of the once flourishing camp." [49]

h) Personalities

Though the rip-roaring early boom days of Panamint might have ended, the townsite and surrounding area still supported some interesting characters, both male and female. Men such as John P. Jones and William M. Stewart (founders of Panamint City), Jack Curran ("King of the Panamints"), Frank Kennedy ("The Duke of Wild Rose"), January Jones, Clarence Eddy ("The Poet Prospector"), Harry C. Porter ("Hermit of the Range"), Shorty Harris, and Chris Wicht ("Seldom Seen Slim") all made their contributions to the history of mining in the Panamint Range.

The women are not without their share of the limelight, too, however. Notable among them was Mrs. Mary A. Thompson, owner and operator of the Panamint lead mine in 1926. Mrs. Thompson had stirred up some local animosity by not allowing prospectors on certain sections that she considered part of her holdings. She was brought to court over this in Independence where she was convicted and given a suspended sentence. Her affairs did not improve, as seen by a later newspaper report that she was searching for her two children, ages 16 and 20, who, she claimed, had been spirited away by "the lawless element of Death Valley," consisting of "numerous bootleggers who ply their lawless trade far from the seeing eyes of the law." Despite their attempts to steal her mine because she had attempted single-handedly to drive them from the region, she did not intend to give in: "I will fight them until I get my children back and rid Death Valley of them." [50]

In the mid-1930s Mrs. Thompson was still in trouble. Convicted on ten counts of failing to pay wages to laborers, and facing 600 days in jail or a $1,200 fine, she was appealing her case to the superior court at Independence. It must have been quite an interesting court session when, during one afternoon's proceedings, Mrs. Thompson became hysterical and fainted, necessitating an adjournment of court for the day. [51]

A 1969 newspaper article mentions another woman living in the Panamint Range area. In 1935 Panamint Annie (Mary Elizabeth Madison) began her reign as "Queen of Death Valley." A truck driver on the New York to Chicago route, she quit that job and moved to Death Valley to live out her days. Residing in a shack at Beatty, Nevada, she spent her time prospecting and puttering around the junk piles at her home. She was still alive in 1969 at age 58. [52]

|

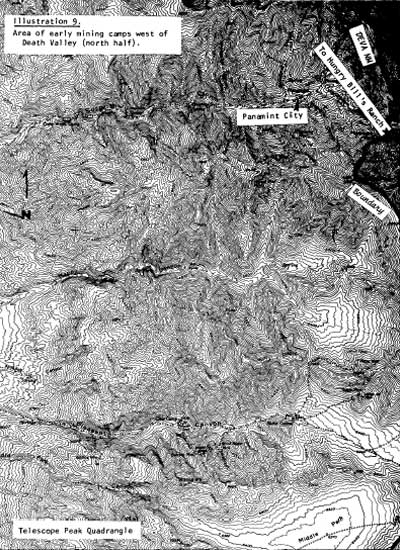

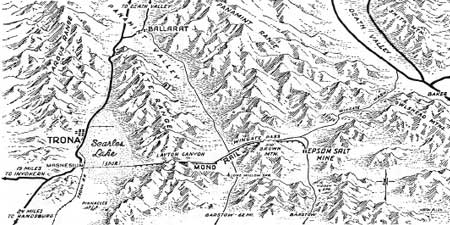

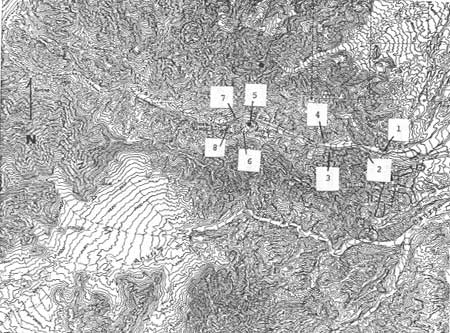

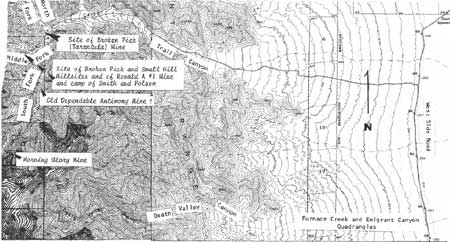

| Illustration 9. Area of early mining camps west of Death Valley (north half). |

|

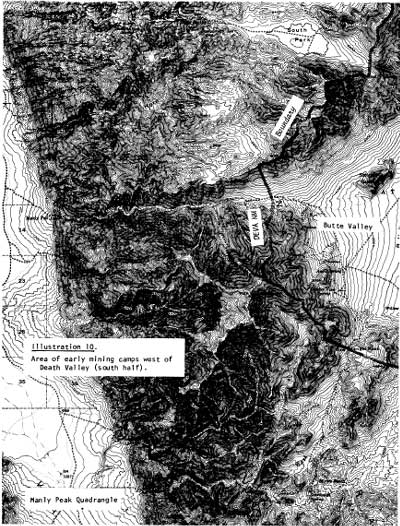

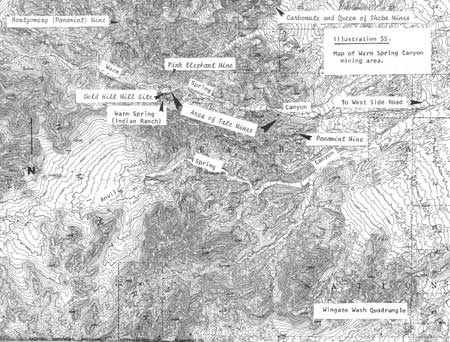

| Illustration 10. Area of early mining camps west of Death Valley (south half). |

i) Sites

The following is an attempt to locate and briefly identify some of the more important mines on the western slope of the Panamint Range. This list is by no means conclusive. An attempt has been made to mention these mines chronologically in order of discovery date. The similarity in name between many of these and other claims within the borders of Death Valley NM makes the task of sorting out relevant material a time-consuming one.

(1) Wonder (of the World?) Mine, Bob Stewart Lode, Mina Verde, and Sunnyside

These mines were among the principal claims filed on by the founders of Panamint City. On 21 June 1873 deeds were submitted by R.C. Jacobs transferring to someone referred to as "Paladio" one-eighth interests in the "Bob Stewart" lode and the Mina Verde, Wonder of the World, and Sunnyside mill sites and timber claims for $1,500 plus other considerations. [53]

In November of the same year notice appeared of the sate by "R.T. [B] Stewart" of a one-half interest in the Wonder Mine for $20,000 to "a San Francisco party by the name of Rains (probably E.P. Raines]." [54] The Wonder Mine was the original find of R.C. Jacobs.

In the Death Valley NM mining office a memo was found with the notation "Scotty's Claim locations." One of these is for a quartz claim "in the Furnace Mountain Mining District," lying on the "Death Valley slope about 40 miles west of Saratoga Springs." Date of discovery was 1 January 1905, the claim to be known as the Death Valley Wonder No. 16 Mine. This would appear to be east of the original Wonder Mine, possibly in the Butte Valley District. [55]

(2) Ino, Jim Davis, Hill Top, Alta, Comstock, Gold Star, World Beater, Big Bill, Elephant, Florence, Gem, General Lee, Gold Note, Golden Terry, Little Till, Lookout, Mammoth, and Summit Mines

By 1897 these claims in Pleasant Canyon were all owned by the South Park Development Company. [56]

(3) Mohawk Lode

This claim was originally filed for record on 18 July 1874 so that a shaft could be sunk and developed for whatever metal it contained. The lode was situated on a hill north of Surprise Canyon and Browns Camp, and was located by C.D. Robinson and R.D. Brown. A second location, filed for record on 8 October 1874 by William Welch and George Ranier[?], locates the claim about 500 feet above the Wonder Mine. [57]

4) Silver Queen Lode

Situated "about 500 yds. SW of the Bullion Lode," this claim was filed for record on 22 August 1874 by C.D. Robinson and John Mantel. [58]

(5) Homestake Lode Home Stake Lode

Two claims by this name appear on the records. The Homestake Lode "situated about 3/4 mile from the mouth of Woodpecker Canon on w. side of the gulch" was filed for record on 7 September 1874 by W.W.(N?) McAllister.

The Home Stake Lode "about 1/4 mile East of Hemlock [Mine]" was filed for record 22 September 1874 by John Kelle and J.B. Durr. [59]

(6) Sheba Lode

This was situated near the summit of the divide between Marvel Canyon and "Canon Gulch," about one-half mile from the divide separating Surprise and "Happy Valley" (Happy) canyons. It was filed for record 8 September 1874 by persons unknown. [60]

(7) Sun Set Mine

A relocation of the Star of Panamint, this claim was filed on 20 October 1874 by Henry Carbery(?), W. McCormick, and W. Scott. [61]

(8) Nellie M Mine

This mine, not to be confused with the Nellie Mine north of Hungry Bill's Ranch in Johnson Canyon, was filed for record on 2 November 1874 by John Small, R.M. McDonell, Charles W. Dale, and L. Rodepouch. It was situated in Woodpecker Canyon on the west side "opposite the third ravine." [62]

(9) Star of the West Mine

Filed for record on 1 December 1874, this mine, located by J.J. Gunn, John Gough, and John Williams, was situated on the west side of Woodpecker Canyon about 200 yards north of the Bismark Mine. [63]

(10) Christmas Lode

"This lode is situated on a hill whose ridge runs nearly eaqual and paralell with Sour Dough Canon, and about one mile from Surprise Valley, said lode is situated between the red formation nearly at the Base of said hill and runs for thirty along crest of the hill Fifteen hundred feet to a white formation at the Northerly line of the lode." It was filed for record 31 December 1874 and claimed by Wellington Hansel Jackel. [64] A North Extension of the Christmas Lode comprised 1,500 feet on the north side of Surprise Canyon filed for record 5 February 1875 by John Fruke, Arthur Bryle, Michael Bryle, and E.H. Boyd. [65]

(11) Christmas Gift Mine and Co. No 1 Mine

To add further confusion, this claim was filed for record on 3 January 1875 by Walter R. Maguire and R.J. McPhee. It was situated "about 300 feet more or less in a North by East direction from the Harrison boarding house. . . ." [66] The No. 1 Mine joined the east end of the Christmas Gift, and was located 5 July 1896 by John Casey, Charles McLeod, and John Curran. [67]

(12) Exchequer Lode

James Dolan, W.W. Kitten, and Thomas Sloan filed this claim about one mile west from the head of Woodpecker Canyon on 25 October 1874. [68]

(13) North Star Mine

Filed for record on 20 January 1875 by M.G. Fitzgerald, A. McGregor, D.J. Sweeny, and M. Holland, ". . . this Ledge to be known as the 'North Star' . . . is situated part on the East side of a ridge running into Narboe Canon & crossing the divide about 1,000 feet West of the Gipsy Bride ledge, between Surprise Valley and Narboe Canon and about 2-1/2 miles in a Northwest direction from the town of Panamint." [69]

(14) Argenta Lode

This claim was filed 27 April 1875, and was located in the center of the west fork of Silver (Sour Dough) Canyon. [70]

(15) Uncle Sam Lode

On 11 April 1880 John Lemoigne filed a claim on the Uncle Sam Lode, situated one mile north of the Torine Mine. [71] (This latter was located 3/4 mile south of the Gambetta Mine and one mile east of a spring in Happy Valley Canyon.) Another Uncle Sam Lode was recorded 17 December 1883 in the Union District about one mile East of the Barns Mill site. [72] In 1931 an application for a patent for an Uncle Sam Lode in the Slate Range Mining District appeared. [73]

(16) Magnet Mine

First mention found of this mine was an 1884 notice that this property in the Telescope Range, south of Panamint, owned by Spear and Thompson, was doing well, much development work having been performed in the past few months. [74] Another report of the mine in 1884 called the Magnet "the only mine in the district [Panamint District] which promises good returns." [75]

(17) Grand View Mine Anaconda Mine

This mine, located rather nebulously "2 miles in northerly direction from spring in Emigrant gulch and about 2 miles in southerly direction from Mineral Hill and about 5 miles in NW direction from Anvil Springs and just south of Buckeye Mine in Panamints," was discovered by W.M. Sturtevant and recorded 11 October 1888. [76] By September 1892 a Grand View Quartz Mine in the Panamint Mining District was owned by the Death Valley Mining Company. The location given of T21S, R45E, would seem to place the mine east of the Panamint City area and north of Gold Hill. [77] This is probably the same mining company owning the lodes in the Gold Hill area. The Death Valley Mining Company, represented by J.H. Cavanaugh, was listed as being delinquent with $23.96 in taxes in 1912. The properties concerned were Lot No. 62, the Anaconda Mine, and Lot No. 63, the Grand View Mine. [78]

In February 1917 the Anaconda Mine (20 acres) and the Grand View Mine (18 acres), owned by John W. Cavanaugh and the Death Valley Mining Company, were offered for sale by the Inyo County tax collector. [79] The two properties were still being advertised a month later. The least amount for which the properties could be purchased was $281.50. [80]

A note in the mining office at Death Valley National Monument stated that the "Anacada (Anaconda?)" quartz and Grand View quartz mines were located near Panamint City in Woodpecker Canyon, "a stones throw away" from the monument boundary. [81]

(18) Willow Spring Mine

This mine, recorded in 1896, was located three miles west of Panamint Toms stone corral. This probably refers to the stone structure up Pleasant Canyon. [82]

(19) Mountain Girl Mine

In 1930 this gold mine was situated at the head of Happy Canyon, about four miles south of the Panamint City townsite. [83]

(20) Black Rock Nos. 1 2 3 and 4

These quartz claims in the Panamint Mining District were deeded in 1922 by J. B. Oven to Mrs. C. Kennedy. [84]

(21) New York Idaho and Dolly Varden Mines

In 1898 a one-third interest in these claims was given by J.F. Ginser to Peter B. Donahoo for $10. [85]

(22) Republican Mine

A mine owned by George Montgomery and associates, it was working steadily and milling high-grade ore in the early 1900s. [86]

(23) Cooper and Mountain Boy Mines

Located near the base of Sentinel Peak, these were owned in the early 1900s by the Gold Crown Company, which intended building reduction works. Much high-grade ore was present. [87]

(24) Valley View Mine

This claim, recorded in 1896, was located on the west side of the Panamint Range, one mile south of Pleasant Canyon and 1-1/3 miles east of Post Office Spring. [88]

2. Gold Hill Mining District

a) History

Some confusion in researching Gold Hill results from the fact that two similarly-named regions existed in the vicinity of Death Valley. A very early Gold Hill Mining District was formed east of Death Valley in the 1860s by a certain Mr. Shaw, and accounts from this area, also referred to as Gold Mountain, appeared quite frequently for a time. The Gold Hill region within Death Valley National Monument is in its southwest corner, in the Panamint Mountain Range, at the northeast end of Butte Valley and north of Warm Spring. It did not see its first activity until around the 1870s. [89]

On 7 May 1875 a Certificate of Work on the Gold Hill No. 1 claim was filed, the work consisting only of an open cut.

It is doubtful that this claim was actually located on what is today known as Gold Hill, because an 1881 location notice for the Bullion Mine, "formerly known as Gold Hill No. 1, Richmond, and Victor Mine," filed by Robert Mitchell, describes it as being situated "at or near head of Quartz Canyon, about 2-1/2 miles from Town of Panamint." [90]

The first positive documented evidence of mining activity occurring on the Gold Hill just north of Butte Valley consists of several site locations filed by Messrs. R.B. Taylor (president of the Citizen's Bank at South Riverside), W.C. Morton, and R.W. Beckerton of South Riverside, San Bernardino County, California. [91] These early claims were filed within the Cleaveland Mining District, which at some early date encompassed, or was thought to, some of these mining properties. No information on the boundaries or establishment dates of this district were found in the Inyo County Courthouse.

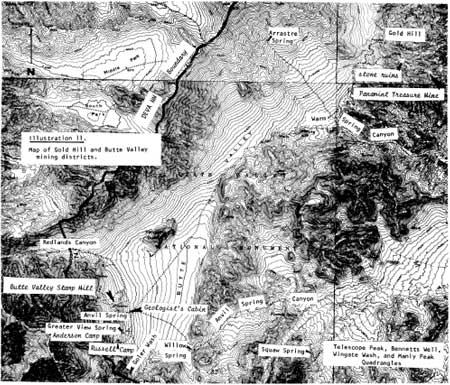

|

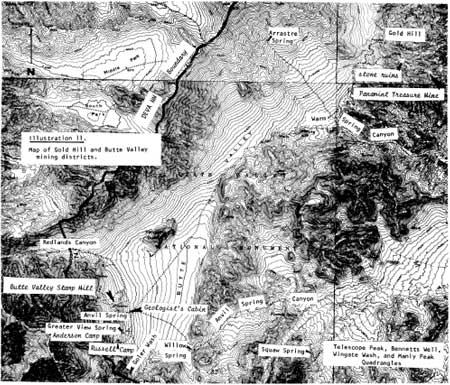

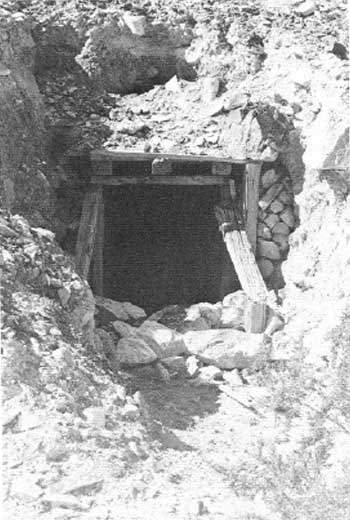

| Illustration 11. Map of Gold Hill and Butte Valley mining districts. |

The ten mines these men located probably included some of the following:

(1) Taylor Quartz Mine and Mill Site

The Taylor Quartz Mine (20.54 acres), situated in the Cleaveland Mining District one hundred yards west of the Treasure Mine, was located first on 11 May 1889 and relocated on 28 August 1890, probably to change the mining district name and at the same time affirm ownership by the Death Valley Mining Company. It was recorded in the district 11 May 1889 and 1 September 1890, and was filed with the county recorder on 6 June 1889. Over $100 worth of assessment work was carried out on the Taylor Mine at Gold Hill, then said to be located in the Panamint Mining District, for the year 1890. The mine was subsequently patented on 21 December 1893. [92]

The directions given for the associated Taylor Mill site (4.42 acres) variously describe it as being located in Indian Toms (also referred to as Panamint Tom's) Canyon, four miles easterly from Gold Hill, and about two or two and one-half miles east from Butte Valley. Water from the mill site, to be used for mining, milling, and domestic purposes, was to be conveyed partly by six-inch-diameter iron pipes and partly by a ditch two feet wide and one foot deep. The mill site, located on 28 August 1890 by the Death Valley Mining Company, and recorded 1 September 1890, was patented on 21 December 1893. [93]

(2) Gold Hill Quartz Mine and Mill Site

The Gold Hill Quartz Mine (19.66 acres) was first located on 30 April 1889 by Morton, Beckerton, and Taylor. Said to be situated in the Cleaveland Mining District, five miles west of Death Valley and about 2-1/2 miles east of the "Chief Mine, it was recorded in Inyo County on 6 June 1889. The mine was relocated in the Panamint Mining District on 28 August 1890 by the Death Valley Mining Company, with the following note appended to its papers:

The above notice was recorded through error in what was thought to be Cleaveland Mining District but upon the 30th day April 1889 and [sic] rerecorded in Panamint Mining District Inyo County Cal. upon day and year as above stated.

The mine location was given as on the north slope of Gold Hill, about two miles east of the Chief Mine and about 500 yards east of the Treasure Mine. Over $100 worth of assessment work was performed on the Gold Hill Mine for the year 1890, and it was subsequently patented on 1 May 1893. [94]

The associated five-acre mill site plus water recorded in the Cleaveland Mining District on 30 April 1889 were to be used by Morton, Beckerton, and Taylor in connection with mining, milling, and domestic purposes. Both mill site and water claim were said to be situated in Marvel Canyon, about five mites west of Death Valley. They were recorded in the Inyo County recorder's office on 6 or 7 June 1889. [95]

(3) Death Valley Mine

The original Death Valley claim in the Panamint Mining District, "situated 1/2 mile south of where the Panamint and Death Valley Trail crosses the summit and on the Death Valley side of the ridge," was discovered by John Lemoigne and others on 6 June 1879. The next possible mention of the claim occurs in the form of a location notice for a Death Valley Mine, situated in the Cleaveland Mining District, "about 1-1/4 miles north of Chief Mine." It was located 13 May 1889 by Taylor and Beckerton and was recorded on 6 June 1889. The claim was evidently relocated and rerecorded on 14 November 1890 by the Death Valley Mining Company, who described the mine as being "Situated 1-1/4 mile NE of Chief Mine and about 2 mites North of Death Valley Mining Company's Boarding House at Gold Hill and adjoins the Beckerton Mine to which it runs parallel in Panamint Mining District." A third relocation notice by the Death Valley Mining Company on 9 August 1893 located the claim "about 1-1/4 miles NE of 'Ibex' Mine and about one mile north of Death Valley Company's Boarding House." Possibly the Ibex Mine is a later relocation of the Chief Mine, about which the writer could find no mention in the county courthouse records. [96]

(4) Treasure Quartz Mine

This claim (20.39 acres) was first located on 30 April 1889 by Beckerton, Morton, and Taylor. Said to be situated in the Cleaveland Mining District, two miles northwest of the "Chief Mine," it was recorded in the county records on 6 June 1889. According to the survey plat of the claim, the mine was relocated on 28 August 1890 and rerecorded 1 September 1890. At the request of R.B. Taylor, president of the Death Valley Mining Company, for an inspection of the claim, the Panamint Mining District recorder found that over $100 worth of assessment work had been accomplished at the mine for 1890. It was patented on 20 March 1893. [97]

(5) No 1 (No One) Mine

This claim, situated in the Cleaveland Mining District, 1,000 feet west of the Taylor Mine and joining the Gold Hill Mine on the east, was located 10 May 1889 by Morton, Beckerton, and Taylor and recorded with the county on 6 June 1889. Over $100 worth of assessment work was performed on the mine in 1890. Whether or not this mine is a relocation of the Gold Hill No. 1 located in 1875 is conjectural. [98]

(6) Silver Reef (Reefe) Mine

This claim was first recorded on 6 June 1889 in the Cleaveland Mining District, having been located on 17 May 1889 by Morton, Taylor, and Beckerton. It was relocated and refiled on 11 December 1890 by the Death Valley Mining Company. In the relocation notice its position is given as "1/2 mile west from Death Valley Mining Company's Boarding House at Gold Hill and is crossed by trail leading from Gold Hill to Panamint in Panamint Mining District." [99]

(7) Ibex Mine (formerly Chief Mine?)

This claim, situated "alongside trail leading from Panamint to Gold Hill about one mile west from Death Valley Mining Company's Boarding House at Gold Hill," in the Panamint Mining District, was not located and filed on until December 1890 by R.W. Beckerton, so it was probably not one of the original ten Gold Hill properties. [100]

(8) May Mine

This claim was located on 7 May 1889 by Morton, Beckerton, and Taylor, and recorded with the county on 6 June 1889 in the Cleaveland Mining District 14 mile southwest of the Chief Mine. Rerecorded and refiled on 11 December 1890 by the Death Valley Mining Company, its location was further stated as "3/4 mile west from Death Valley Mining Co's Boarding House being crossed by trait leading from Gold Hill to Panamint and is on west slope of Gold Hill" in the Panamint Mining District. [101]

(9) Breyfogle Mine

This claim "west of trail going to Panamint and about 600' south of Ibex Mine," was located in the Panamint Mining District on 9 August 1893, and so was not one of the original, ten claims in the area. It was a relocation of the "Bryfogle [sic] Mine' 600' south of Ibex Mine to north of Gold Hill trait which it crosses." A man by the name of S. Smith relocated the mine again as the "Bryfogle Quartz Mining Claim" on 1 January 1896. The mine was described as a lode of quartz-bearing copper adjoining the Nutmeg Mine "on SW side tine and is south of Panamint Trail about 1000 feet and North West of Gold Hill about 3/4 of mile. Is on low divide between Panamint Mts. and Gold Hill." A second notice of relocation in 1896 gave its spelling as "Breyfogle" again and stated it was a relocation of the Breyfogle Mine formerly claimed by Henry Gage. [102]

(10) Oro Grande Mine

The first mention found of this claim was a 9 August 1893 relocation notice filed by Henry T. Gage. The location given was "on south slope of Gold Hill about 2000' west from Taylor patented mine and about 2000' SW from Treasure patented mine in Panamint Mining District." Four years earlier, on 27 May 1889, a Notice of Appropriation for the waters of Oro Grande Springs, "situated 3 mites west of Chief Mine and about 8 miles north of Anvil Spring in NW corner of Butte Valley in Butte Valley Mng. District," was filed by Frank Winters and Stephen Arnold. The waters, to be used for mining, milling, and domestic purposes, were to be developed by ditches, pipes, and flumes. [103]

(11) Beckerton Mine

This mine was located 14 May 1889 by Morton, Beckerton, and Taylor, and recorded with the county on 6 June 1889. It was situated in the Cleaveland Mining District, 1-1/4 miles northeast of the Chief Mine and 1,000 feet north of the Death Valley Mine. [104]

(12) Georgia Mine

This claim was located 19 May 1889 and recorded on 6 June 1889. Also in the Cleaveland Mining District, it was situated 1-1/2 mites north of the Chief Mine and was supposedly a northern extension of the Breyfogle Mine. [105] If so, there must have been an earlier recordation of this latter mine than the one found by this writer.

According to the Inyo Independent the mines in the Gold Hill region were first discovered by an Indian who imparted the information to a man named Carter who immediately told R.B. Taylor, C.M. Tomlin of Riverside, and a Mr. Nolan about them. These four men went and examined the ledges, located several claims, shipped in provisions, and hired two young men, Stephen Arnold and Frank Withers, to work their claims. As incentive they gave the boys some nearby properties, and then returned home. Although word of the find slowly leaked out after the boys returned to the coast, causing others to take an interest in the area, no one knew much about the ore, which was rumored to range from $80 to $250 per ton. It was also said that Taylor was contemplating opening a road into the property. [106]

Papers incorporating the Death Valley Mining Company "to do a general mining business" for fifty years were filed in the office of the Secretary of State on 13 July 1889. The principal place of business was South Riverside, San Bernardino County, California, and the following were listed as directors: R.B. Taylor (S. Riverside), W.C. Morton (San Bernardino City), R.W. Beckerton (S. Riverside), H.R. Woodall (S. Riverside), and J.H. Taylor (S. Riverside). The corporation had one million dollars of capital stock divided into 10,000 shares worth $100 each, though the amount of capital stock actually subscribed was $60,000, raised by the five directors plus James Taylor, Sr., and W.A. Hayt. [107] Soon after its organization the company obtained U.S. patents for at least five of its mines: Treasure (20 March 1893), Gold Hill (1 May 1893), Taylor (21 December 1893), Grand View, and Anaconda.

Further news of the new camp was available a couple of months later, when it was reported that the "ores are rich in gold, the veins strong and well defined, and as far as opened have every indication of permanency." [108] Prospects appeared so encouraging and Taylor and his associates had accomplished enough labor that reduction works seemed warranted. Other miners had also moved into the area and owned promising properties. In these early days at Gold Hill it is probable that Indian labor was utilized at the mines and that they were taking the ore three miles west to Arrastre Spring to process it.

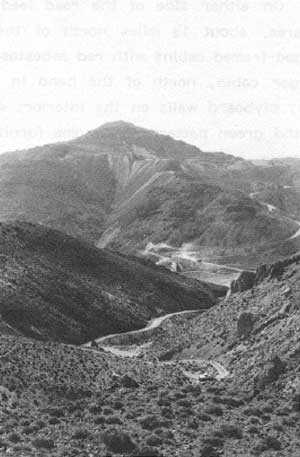

By 1896 the mines at Gold Hill were still being worked. A Richard Decker was evidently running the operations for R.B. Taylor, and the veins still looked promising. [109] The mines produced so well, in fact, that by the fall of 1897 R.B. Taylor and his business partners James P. Mathes of Corona and W.A. Hayt of Riverside were able to sell a group of five of their free-milling mines to an English syndicate for $105,000. The Independent reported that "This is the most important sate of Inyo mining property that has yet transpired in the 'southeastern' districts. . . ." [110] The mines involved were the Treasure, Taylor, Gold Hill, Grand View, and Anaconda, located "about seven miles southeast from Panamint and ten miles northeast from the head [mouth?] of Pleasant Valley; are at the north end of Butte Valley and near the head of Anvil Canyon. . . ." Dumps In the Gold Hill area had already accumulated 500 to 600 tons of ore, not free-milling as had been rumored, but impregnated with copper and iron. Water could be piped to the mines from Arrastre Spring and of course lumber was available on the higher mountains. The only major problem hindering development revolved, as usual, around lack of easy access to mine and market. It was suggested that a road be cut down Butte Valley past Anvil Spring to connect with the old "Coleman road," probably meaning Wingate Pass. [111]

Taylor evidently had negotiated a further sale of Gold Hill property by 1899, for reports were found that he then sold the Gold Hill mine "known as the Death Valley mining property" to New Yorkers for $207,000. They were supposedly going to spend another $100,000 erecting a forty-stamp mill, bringing in other machinery, and in making needed improvements. The sale was made because the owners (Taylor and Beckerton) did not have sufficient capital to fully develop the mine. [112] By the next year the Death Valley Mining Company had reportedly been doing extensive work in opening up its properties in order to fully determine their extent and richness. A sixteen-foot vein of solid auriferous ore had been exposed, and some sort of reduction works were needed. An Inyo newspaper reported that

This section in the near future will become an important factor in the gold production of the State. The veins are large, the nature of the ground admitting of extraction at a minimum expense with water and fuel handy. [113]

The year 1900 also saw the entrance of a new mining company into the Gold Hill region as the Gold Hill Mining Company, a wealthy New York-based firm, announced intentions to begin activities there around the first of March. [114]

Future transactions concerning the Gold Hill Mine are somewhat confusing. In April 1900 the Independent reported that this claim had been resold on the seventeenth "to Mr. Taylor, a banker of South Riverside, for $207,000." [115] In May an article stated that the Gold Hill "lead mines" had been sold to some southern California capitalists (possibly including Mr. Taylor) who were envisioning commencing operations there immediately. [116] By 1904 the Gold Hill Mining and Development Company was in some financial difficulty, appearing on the Delinquent Tax List of Inyo County for the year 1903 because of taxes due on the Taylor Mine and Mill Site (Lots 39A and B, comprising twenty-five acres), the Gold Hill Mine (Lot 37, twenty acres), and the Treasure Mine (Lot 38, twenty acres). The amount assessed the company was $39.46. An assessment of $8.10 for the very same property was made against an L.A. Norveil, who apparently held a mortgage on-these properties, possibly as executor of the W.H. Greenleaf Estate that is mentioned in the assessment. [117] Suffice to say, ownership of the claims had become fairly involved by this time.

No detailed mention of the mines in this area over the next few years came to light. In 1906 two other persons, Ralph Williams and Bob Murphy, were mentioned in connection with mining properties on Gold Hill, and both reports indicate that satisfactory progress was still being made in the area. [118] By 1911 the Delinquent Tax-List of Inyo County listed John W. Cavanaugh as being assessed $25.01 in state and county taxes for the Anaconda Mine (Lot No. 62 Mineral Survey, twenty acres) and the Grand View Mine (Lot No. 63 Mineral Survey, twenty acres). The Gold Hill Mining and Development Company, of which Cavanaugh was the secretary, was assessed $25.51 in overdue state and county taxes again for the Taylor Mine and Mill Site and the Gold Hill and Treasure mines. [119]

In February 1917 these three mining locations are reported as having been sold to the state on 28 June 1904 for 1903 taxes (Deed No. 72). Since no effort had been made in the past five years by the Gold Hill Mining and Development Company to redeem the properties, they were being offered for sale. The total assessment levied, including overdue state and county taxes for 1903, penalties on delinquency and costs, total interest at 7% per year from 1 July 1904, plus smaller miscellaneous costs, fixed the price asked at at leas? $82.60. [120]

The Anaconda and Grand View mines had already been sold to the state on 25 June 1901 for non-payment of taxes during 1900. Cavanaugh and the Death Valley Mining Company were being assessed a total of $149.50 in back taxes, $27.19 in penalties, and $84.99 in total interest charges. This plus miscellaneous costs brought the minimum purchase price of the two properties to $281.50. The minimum purchase price of the Taylor, Gold Hill, and Treasure mines, still up for sale, had fallen slightly, to $799. [121]

The 1932 Journal of Mines and Geology presents a capsulized summary of the current workings at the Gold Hill Mine. It comprised four patented claims on the east slope of the Panamints at an elevation of 5,400 feet. The owners at that time were Fred W. Gray of Los Angeles and William Hyder of Trona, California, but the property was under lease at the time to Miss Louise Grantham, also of Los Angeles. Gray and Hyder said the property, patented in 1894, had been deeded to the state, from whom they bought it in 1919. The owners claimed there were three tunnels on the property (the longest, 300 feet) from which were coming "lead carbonates and galena, with gold and silver as associate minerals." Rumor was that Miss Grantham intended to construct a mill to process the ore at Warm Springs, about four miles southeast of Gold Hill. [122] (More information on this mill will be found in the Warm Spring section of this report.) A 1948 USGS Bulletin stated that the Gold Hill Mine, producing gold, silver, and lead, was owned (or operated) by Messrs. James and Dodson of Lone Pine, California, in 1940. [123]

In 1951 the Journal mentions several Gold Hill area mines: 1) Golden Eagle Group of six claims on the southwest slope of Gold Hill (T22S, R46E, MDM). These were owned by Louise Grantham and development consisted of a 40-foot tunnel with 10-foot winze. High-grade gold, silver, and copper was present, but in this year no activity was recorded; [124] 2) Panamint Treasure Mine (Taylor, Treasure, Gold Hill) on the southeast slope of Gold Hill. This ninety-acre holding comprised the three patented claims above plus three unpatented fraction claims and a mill site at Arrastre Spring, all owned by Louise Grantham and associates of Ontario, California. A 50-foot adit and a 100-foot adit were present on the Taylor Claim with ore assaying on the average 1.02 ozs. gold, 9.4 ozs. silver, and 3.2% lead. From 1931 to 1941, 150 tons of ore were shipped and 300 tons milled, but the property was now idle; [125] 3) Red Eagle Group (Blue Bird Group) on the southwest slope of Gold Hill comprised six unpatented claims also owned by Louise Grantham. Workings on the now idle property consisted of a 50-foot shaft, an open cut, and a 100-foot adit. Assays on the ore returned lead, silver, and smaller amounts of gold. [126]

A partial list of mining claim locations within the monument in 1960 reveals that the Gold Hill area contained at least twelve unpatented and three patented gold, silver, and lead claims. [127] The files in the Death Valley National Monument mining office offer a more complete look at the more recent claims and the present mining situation in the Gold Hill area:

In 1975 Gold Hill proper contained fifteen claims owned by Ralph Harris of Victor Material Co. of Victorville, California, and his son Harold: the Treasure Quartz Mine (patented), Taylor Quartz Mine (patented), and Gold Hill Quartz Mine (patented); Panamint Treasure Fractions #1, #2, and #3 (located 20 February 1937); Golden Eagle #1, #2, and #3 (located 30 July 1935); Red Eagle #1, #2, and #3 (located 31 July 1935); and Bullet #2 and #3 (located 30 April 1942), and #4 (located 19 September 1956). All claims were located for gold, except the Red Eagle Group, which was located for lead and silver. The patented Taylor Mill site, although associated with mining at Gold Hill, is located at Arrastre Spring about four miles west. The Red Eagle Mill site (located either 19 or 24 April 1946) is located at Six Springs, two miles northeast of Arrastre Spring in Six Spring Canyon.

b) Present Status

The claims listed earlier are all included within the Panamint Treasure Claim Group and lie in the vicinity of Gold Hill, north of Warm Spring Canyon, in protracted Sections 14, 23, and 24, T22S, R46E, MDB and MDM.

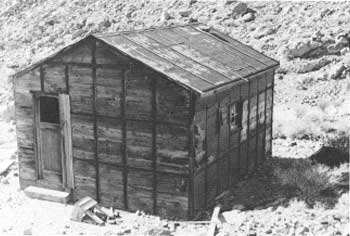

(1) Gold Hill Area

The Gold Hill area is reached by a rough dirt road taking off in a northerly direction from the Butte Valley Road about 2-1/2 miles west of its intersection with the Warm Spring Canyon Road. About 1/4 mile north on this road some ruts veer to the west, leading about another 2-1/2 miles up a steep four-wheel-drive slope to Arrastre Spring. Proceeding north on the main road, however, for about another two miles leads to a fork in the road, the northernmost route leading up over a hill to a site marked "Prospect" on the USGS Bennetts Well quadrangle. This area is on the Bullet claim, and according to on-site observations made by Rich Ginkus in July 1974, the site contains a 30-foot shaft fifty feet south of the road approximately 1,500 feet from the road's end where remains of two old wooden buildings were found along with a rusting gas or diesel generator. A nearby adit about 100 feet long contained mine rails. Three other smaller cuts are also present. It did not appear that any recent work had been done in the area. [128]

The southern fork leads to an area marked "Mine" (Red Eagle Claim) on the USGS quadrangle. This road has been extended since the area was officially mapped, so that instead of ending in the wash below the prospect area, it switchbacks up the side of the hilt, finally trending on east toward the summit of the saddle south of Gold Hill. The mine workings viewed by this writer along this newer extension of the road appear to be exploratory in nature, consisting of small adits and open cuts along the sides of three gullies, with no structures or mining artifacts in association.

The writer followed along the road to about the 5,000-foot elevation point on the saddle below (south of) Gold Hill. Here were found the remains of a small stone structure, whose walls measured approximately twelve by fifteen feet. Some wood scraps, fragments of metal cans, and pieces of murky white glass lie in and around the ruins. About thirty-seven paces northeast is a small beehive-shaped mound of stones one to two feet high--probably a claim marker. This structure was the only item of historical interest found during this exploration of Gold Hill.

|

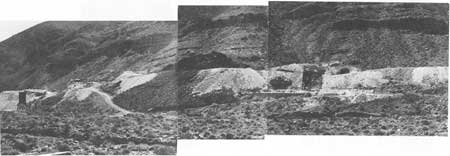

| Illustration 12. Ruins of small stone structure on saddle south of Gold Hill, view from northwest. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 13. View of stone structure from southwest. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978 |

(2) Panamint Treasure Claim Group

Investigation of the Panamint Treasure Fraction #1-#3 lode claims, made a month later, proved much more productive. The best way to reach the area (other than by helicopter) is on foot via a burro trail leading west from the Sunset Mine, which is located at the end of a road veering west from the stockpile of the Montgomery (Panamint) Talc Mine. After an exhausting uphill climb of two hours duration the site was found on the southeast slope of a ridge southeast of Gold Hill.

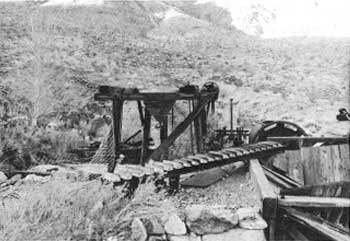

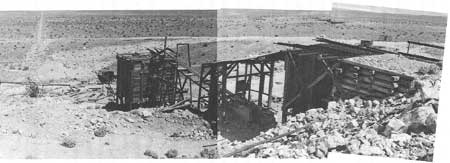

The complex consists actually of two distinct sites. The most easterly one contains two adits--an upper 226-foot tunnel that was worked and a lower one used as living quarters. The second site, around west on the south slope of the same ridge, contains a third adit and a tent site. An extensive tramway system still exists at the first location, complete with cable and supports This was used to transport ore from these main workings down the mountainside 1-1/2 miles probably to the wash just north of the ridge that lies northwest of the Warm Spring Canyon-Butte Valley roads junction. Time did not permit driving up this wash to see if any structures remained at the bottom of the tramway.

|

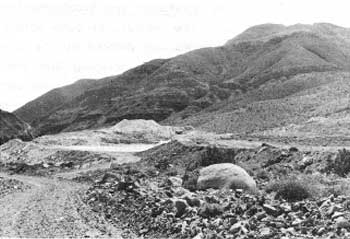

| Illustration 14. View toward west-northwest of Panamint Treasure Claim. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 15. Model A frame possibly supporting air compressor for Panamint Treasure adit. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

Reportedly, work on the lodes here stopped in 1941, a date that corresponds closely with the cultural remains left on site, of which there are many. Examining the property is difficult because of the steepness of the slope and the fact that it is covered with loose rock from mining activity. Descent to the lower workings is possible only by holding on to the tramway cable.

In front of the upper adit is a Model A frame containing a Phillips 66 battery, which might have functioned as an air compressor. A pipe with a gate valve leads from here to a nearby adit. Various debris (tin cans, rubber hosing, nails, hand drills, a windlass, an axe handle, and drill stems) is scattered over the slope. In the upper adit, whose main tunnel branches off in about seven different directions, creating a fairly large open central area, were many items of interpretive interest. Just inside the entrance on the floor is an almost-full box of bits and some drills (labelled "Timken Roller Bearing Co., Mt. Vernon, O."). A large Fairbanks scale on wheels stands nearby, all its weights still in place. Also on the floor near the entrance are an adze handle, coiled rubber hosing, and a small rusted oil can. In the exploratory tunnel furthest west are two picks leaning against the wall. The tunnel at this point was being excavated upwards for a height of about six feet, and the entire excavation was filled with crickets. Nearby are the remains of a dynamite box and a burlap specimen bag.

As stated earlier, several exploratory tunnels branch off from the main one, but some were backfilled or went in only a few feet. On the south side of the main tunnel is a stoped-out area below a short cut-off bank. An ore cart built from half of a steel drum placed on wheels was pulled by a cable up short wooden tracks to the main tunnel level. Pieces of rope, big sheets of burlap, and blanket remains are scattered around. On one of the latter is imprinted: "Plummer Bag Mfg. Co., Bags, Tarpaulins, & Tents, San Pedro & L.A., 108#. An old shoe, made in Taiwan, lies on the floor. Atlas powder box fragments and fuses are also found.

|

| Illustration 16. Adit to Panamint Treasure Mine to right, storage pit to left. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 17. Adit used as living quarters, Panamint Treasure Mine. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

Near a shallow pit just outside the tunnel entrance is a dugout storage area. Scraps of the Los Angeles Examiner, dated in April (probably 1940 or 1941 judging from the news content), and some canvas bags (sample sacks?), one with a drawstring, were found here. Further searching revealed four dry-cell batteries fastened together, some waxed paper from dynamite boxes, and the head of a sledgehammer.

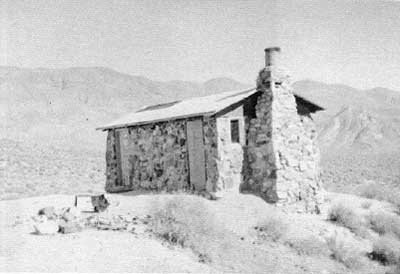

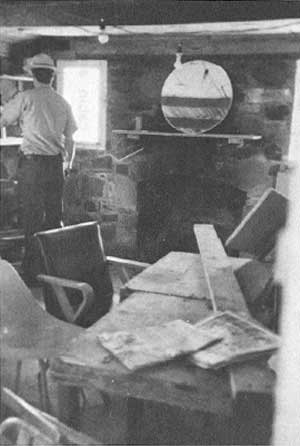

Below this first tunnel is a stone wall, undoubtedly shoring up the entrance and providing a working platform area. The next tunnel downhill was definitely used as living quarters. A stovepipe projects from the entrance, which has a wood frame opening to which a canvas door is attached. In front of the door were found soldered tin cans and Mason jars. Inside the tunnel are a wealth of household goods: Alber's Flapjack Flour cases, Fluffo vegetable shortening (4 lbs./49¢); a 1941 Saturday Evening Post a dime western magazine; a Los Angeles Times dated 15 December 1940; a five-gallon oil can; a shovel; another Mason jar with vertical ridges encircling it; a saw; a cooking pan; a wall shelf fashioned from an explosives box; a coffee can full of pinto beans; a can of Diamond A cut green beans; a 24-1/2 lb. A-1 flour sack made into a pillow covering; two sacks of flour; a spoon; a skillet; strips of jerky in a bottle; two pie tins; a small square pie pan; two small homemade stools; a four-legged table; and two metal bunks, one with a feather pillow. A cardboard box was found addressed to "K.H. Grantham, Wilmington, Ohio." Nearby was a postcard addressed to "Fritz" from "Mother and Dad Gibson." Outside the entrance are a small warming oven with shelves, a homemade pitcher, a milk can with a wire handle, the remains of a water bag, gear parts, and an electric line fastened to the rocks above the door.

|

| Illustration 18. Metal tramway terminus, Panamint Treasure Mine. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |

|

| Illustration 19. View south down slope along route of tramway cable. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978. |