|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION IV:

INVENTORY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES--THE EAST SIDE

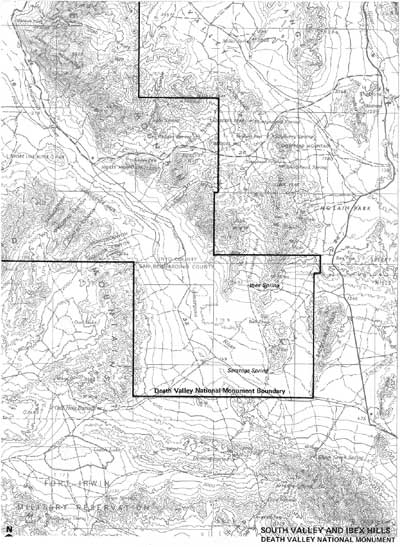

D. South Death Valley and the Ibex Hills

1. Introduction

This section of Death Valley is perhaps the most desolate region within the Monument. Dominated by the dry sink of the Amargosa River, the landscape consists mostly of sand, salt, and the low Ibex Hills. The region has always been isolated from any centers of population, however small, and the present road network completely bypasses. Two spots of vegetation, Ibex Springs and Saratoga Springs, possess practically the only signs of life within the area.

As might be expected, historic activities within this region have been centered around those two springs, which represent the only sources of water in the south valley. Saratoga Springs was known as a dependable water source by 1880, and Ibex Springs shortly thereafter. For most of the ensuring hundred years, the use of these two springs, by travelers entering or leaving the valley, has beer the only activity of note.

Small-scale mining attempts, however, have taken place. The original Ibex Mine was opened in the 1880s, and ran for a few years. A very brief niter rush swamped the south valley with prospectors in 1902, and a more prolonged rush occurred during the Bullfrog boom years. This latter rush saw the brief exploitation of several mines in the Ibex Hills, and an ill-conceived attempt by gold-mad promoters to dredge the floor of the desert. With the demise of the Bullfrog boom, the area reverted to practical desertion until the modern talc mining operators began in the 1930s. With the exception of the dormant talc mines, whose edifices dominate the physical remains in the region, very little is left with which to interpret the earlier years. Time, weather, sticky-fingered prospectors, and salvaging talc miners have combined to erase all but the most minute signs of earlier activities.

|

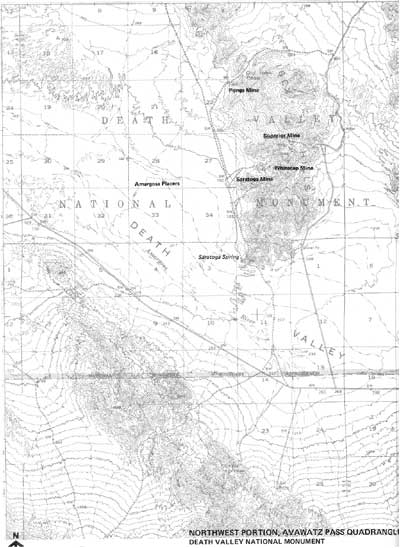

| Illustration 244. Map of South Valley and Ibex Hills. |

In brief, the South Valley and Ibex Hills region has seen periods of short and intermittent life, interspersed between years of practical desertion. The history of the area as a whole is not a continual tale of mans exploitation, but rather a series of brief and unconnected attempts to wrestle wealth from the barren ground. There is little left within the region with which to interpret its spotted past.

2. The Ibex Springs Region

a) Ibex Hills Gold and Silver Mining

1. History

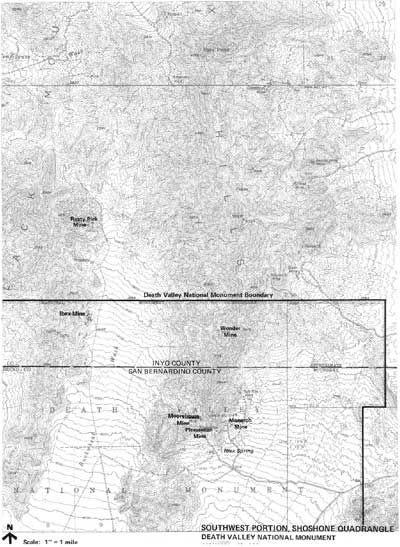

Early references to mining activities in the Ibex Hills area are somewhat questionable, due to vague and contradictory geographic references in the contemporary newspapers and journals. The first serious mining to take place in this region apparently began in December of 1882, with the incorporation of the hex Mining Company--a Chicago based group. The exact location of the original Ibex Mine is undetermined, but it is probably safe to put if within a mile of the Ibex Mine located on the 1951 Shoshone quadrangle.

The Ibex Company had good luck initially, as evidenced by its decision to build a five stamp dry roasting mill in 1883. Following the completion of the mill, several loads of silver-lead ore were shipped out, but production was never extensive. This early mine soon experienced all the problems which would plague later mining efforts in the Ibex region--intense heat, water shortages, exorbitant freight costs--thus preventing the profitable extraction of any but the highest grade of ore. As a result, the original Ibex Mine was never very successful. In 1889 the mine was operated only sporadically due to fuel problems, and by 1892 the mine and mill were idle. [1]

|

| Illustration 245. Southwest Portion of Shoshone Area. |

For the next several years, the Ibex district was deserted, with the sole exception of Frank Barbour, who relocated the Ibex Mine and performed the necessary assessment labor year after year. Then, after fifteen years of isolation, Barbour was suddenly crowded with company--a result of the prospecting wave set off by the Bullfrog boom.

In June of 1906, a party of three prospectors on their way north towards the Greenwater District discovered the Orient Group of claims approximately two miles north of the Ibex Mine, and the rush was on. Within a year, three major claims, as well as many minor ones, had been staked. The Busch brothers, prominent mining promoters from Rhyolite, purchased two of these, the Orient and the Rusty Pick Groups. The third, the Evening Star Mine, one mile from the Rusty Pick, was owned and operated by the Heckey brothers, who moved their wives and families to the site. Meanwhile, Frank Barbour continued to push development on the old Ibex Mine. [2]

Attempts to develop these mines continued throughout 1907 and 1908. By December of 1907, the Orient had forty sacks of ore ready for shipment, and the Evening Star, which boasted a sixty-five foot shaft, had taken out almost twenty tens of ore for eventual shipment. The problems encountered by the mines were emphasized by the cost of $20 per ton freightage, merely to get the ore from the mines to the railroad, twenty miles away. Nevertheless, prospects were bright enough to warrant a Christmas dinner hosted by the Heckey women, and attended by the miners of the region.

Developments continued during the early months of 1908. In February, the Busch brothers bonded the Orient and Rusty Pick claims to a Goldfield operator, and the Heckey brothers readied their first carload of ore for shipment, claimed to be worth $85 to the ton. By May, the Rusty Pick shaft was down to eighty feet. Then, due to a combination of summer heat, lack of development funds and the failure of promising ore leads, this portion of the Ibex District suddenly slowed down. [3]

By May of 1909, a year later, the Rusty Pick Mine, which had been sporadically active, still had only 200 total feet of development work, and had made only one shipment of ore, worth $50 a ton Nevertheless, the Busch brothers managed to bond the mine again, to Chicago and Goldfield operators. The new owners promised immediate and extensive developments, but the promise went unfulfilled.

The following years saw occasional activity, but little real mining. In 1910 the Busch brothers managed to bond the Orient and Rusty Pick once more, but no work was done on the property. Funds were so low on the Evening Star property that the former partners were suing one another to recover the costs of assessment work. Although several men were at work on the Rusty Pick again in 1911, by the end of the year Pete Busch, the mining promoter, was reduced to performing his own assessment work. By this time, the Evening Star group had been abandoned, as John and Melvin Heckey left with their families, to join their brother Ross in Alaska. [4]

In the meantime, a few miles southeast of the "old hex Mine, the area in the vicinity of Ibex Springs had undergone a very similar experience. Like the "old' hex Mine, the Ibex Springs region pre-dated the Bullfrog boom, but did not undergo any serious developments until the effects of that boom had spread southward. The first known miner in this area was Judge L. Bethune, who located three claims at Ibex Springs in April of 1901. When Judge Bethune got drunk and died in the desert in 1905, his mine immediately became lost and subject to all the folk tales peculiar to lost mines. In this case, however, it was not lost for long, for the mine was relocated in January of 1906. [5]

The new locators, primarily Rhyolite men, incorporated themselves as the Lost Bethune Mining Company in October of 1906, and with a capitalization of $1,250,000 began development work. Bunk houses and a boarding house were erected at Ibex Springs during 1907 and by March of 1908 the mine's eight employees had sunk a shaft 200 feet deep, had fifty tons of ore on the dump and had shipped over 300 tons, which averaged $43.30 per ton. Despite this encouraging start, however, the demise of Rhyolite, which curtailed the flow of development funds and increased freighting and supply expenses, had its effect upon the Lost Bethune. Although monthly shipments of high grade ore were still reported in May of 1909, the mine was abandoned the next year. [6]

Five years later the Ibex District experienced a revival of sorts. Leading the way was the old Ibex Mine, still owned and operated by Frank Barbour. The mine employed twenty men in 1915, and was termed a regular shipper. Across the wash to the east, the Wonder Mine had been developed, and plans were announced to erect a mill. In 1916, by which time Barbour had sold out, the Ibex had fifteen men at work, and the new owners were planning to construct a 2,800-foot aerial tramway from the mire on the side of the mountain down to the wagon road below. In 1917, although the Wonder had already become idle, the Ibex was still active. Nineteen men were employed, paid at $4 per shift, and seven or eight tons of ore were being trucked out daily--the tramway had not been built. By 1921, however, the mine was again idle, and this time it had breathed its last. [7]

One other mine bloomed briefly in the Ibex region. The Rob Roy, about one mile north of Ibex Springs, was located in 1914, and by 1915 was described as well developed and shipping ore of good quality. This mine was periodically active as late as 1924, when the owners, the Ibex Springs Mining Company, received a patent for four lode claims and one mill site. As quietly as it had appeared, however, the Rob Roy sank back into obscurity, and with the exception of lonely prospectors who still roamed the desert dreaming of riches, the Ibex region lay quiet. [8]

2. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendation

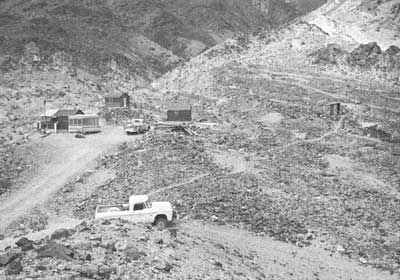

Very little remains to mark the sites of all this activity. Ground explorations have failed to specifically mark the site of the '19th-century mine and mill of the Ibex Mining Company. Given the extensive activities of following years and the prevalent practice of cannibalization, however, this lack of physical evidence is not surprising.

The 20th-century remains are hardly more promising. The main efforts in the Ibex Hills area were centered around the Rusty Pick, Orient, and Evening Star Groups, all of which were north of the Monument boundary, and thus were not examined. At the Ibex itself, sporadic prospecting and development work, which was carried on even into the 1970s, has succeeded in erasing all signs of earlier activities. Examination of these sites reveals unnumbered holes in the ground, but little else.

A similar tale is told at the Ibex Springs area. Here, all trace of early 20th-century mining has been completely obliterated by the talc mining carried on in later years. Thus, with the exception of the buildings at Ibex Springs (discussed below)., there are no remains worthy of preservation consideration in the Ibex Hills area. There is potential for historical archaeology, particularly around the "old" Ibex Mine.

|

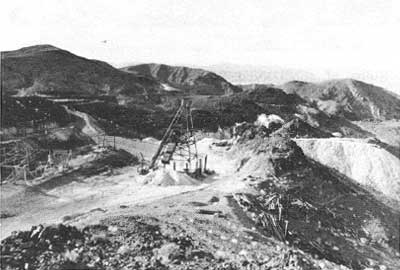

| Illustration 246. General view of the Ibex Mine area in 1978. Note numerous dumps, pits, and cuts in vicinity. 1978 photo by Linda Greene. |

b) Ibex Springs Area Talc Mines

1. History

The last stage of mining activities in south Death Valley opened in the mid-1930s, when John Moorehouse located 16 talc claims a short distance northwest of Ibex Springs. By 1941, Moorehouse had managed to extract 1100 tons of talc. After a short period of idleness, Moorehouse then leased his claims to the Sierra Talc Company in the mind-1940s. Sierra Talc developed the ore bodies extensively, and produced almost 62,000 tons of ore by 1959. By then the talc seams were largely depleted, and the mine was operated only sporadically until about 1968. Site examination leads to the conclusion that no more than assessment work, and very little of that, has been done since the latter date.

Two other talc mines were also operating during this same general time period. Ralph Morris and associates located the Monarch group of four claims in 1938, and operated it until 1945, when it was also leased to the Sierra Talc Company. Sierra Talc operated the mine until 1950, with a total production between 1938 and 1950 amounting to 46,000 tons. The mine was then idle for six years, until it was leased to the Southern California Minerals Company in 1956.

Just to the south of the Monarch is the Pleasanton group of two talc claims, first opened in 1942. The Sierra Talc Company acquired the lease to this group also in 1946, and total production for the mine reached 16,000 tons by 1947. The Pleasanton was then idle for several years, until the Southern California Minerals Company acquired its lease in 1956, and connected the underground workings with those of the Monarch. Operated together, the Monarch and Pleasanton yielded another 7,500 tons between 1956 and 1959, for a total combined production of 69,500 tons. Between 1959 and 1968, intermittent operations were continued, but site examination indicates that little serious production was undertaken during that time. Both the Monarch and Pleasanton mines are now idle, and have been for several years. [9]

2. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

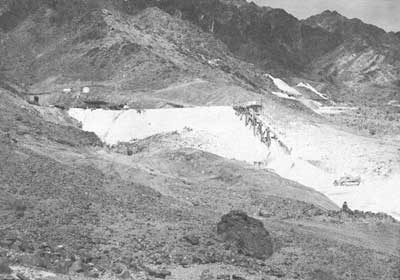

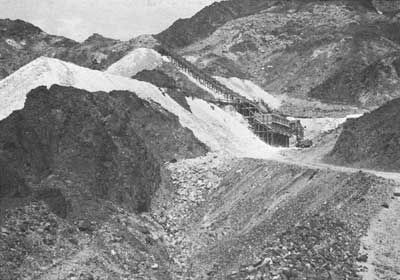

Due to the recent nature of these mining activities, extensive structural remains are present in the area. At the Moorehouse, which consists of three distinct levels, the progressions of mining activities can clearly be seen through the development of mining structures. The lower and middle levels, reflecting the lode mining activities of the earlier years, contain extensive complexes of adits, ore bins, ore chutes and tramway networks. These wooden structures are rather picturesque, are in relatively good condition, but are not of historic significance due to their lack of age. A policy of benign neglect can best be suggested for this complex, for the lack of historic significance does not warrant any preservation funds being spent at this time. Conversely, the mine structures certainly should not be destroyed or carted away, as the value of the complex will obviously grow with age.

The upper level of the Moorehouse reflects the latest period of development and assessment work, being nothing more than an extremely unsightly complex of scars, pits, and heaps left over from stripping operations.

Both the Monarch and Pleasanton also have extensive structural remains. At the Monarch, these consist mainly of a small living compound, containing three 1940s era living shacks, a cookhouse, and various support buildings. These shacks are all of poor construction, although they are still in reasonable shape. They warrant no preservation or concern. The Monarch Mine workings consist of a small complex of adits, tramways and ore bins, all in very poor shape. Again, the best policy should be to let them rest in peace.

At the Pleasanton, more extensive mining structures remain. Like the Moorehouse, the Pleasanton was worked on several levels, with a (collapsed) connecting shaft in between. On the lower level is a large loading dock and tramway network, used for loading both Monarch and Pleasanton ores during the latter years of combined operations. On the upper workings are several shafts and adits, complete with a partial tramway and a wooden headframe. Although interesting, these structures are not nearly as complete as those of the Moorehouse, and benign neglect is again recommended.

Viewed as a whole, the best extant representation of recent talc mining operations in southern Death Valley is contained in the structures of the Moorehouse Mine. The remaining structures at that site are the most extensive, of the best condition, and reflect several different periods of mining activity. As stated before, however, even this complex does not warrant preservation efforts at the moment. The Moorehouse structures should remain relatively intact for a period of time, however, since the only access road to the area brings the visitor (who would have to be a four-wheeler) directly into the front of the Monarch -Pleasanton areas, with the Moorehouse tucked behind a low ridge out of sight. As Such, the Moorehouse will probably remain relatively untouched for some time, and should be kept in consideration far potential future preservation efforts.

|

| Illustration 247. Homestead of Tom Wilson, a former employee of Southern California Minerals Company, who built this complex to avoid paying rent in the company town of Ibex Springs. Photo by Park Ranger Hill, 1962, courtesy Death Valley National Monument library, #2670. This site, adjacent to the workings of the Monarch Talc Mine, had changed very little by 1978, with the exception of natural deterioration of the structures. |

|

| Illustration 248. View of the lower workings of the Pleasanton Talc Mine in 1962, when the mine was still sporadically active. Note the white talc dumps of the Monarch Mine to the upper right. Photo by Park Ranger Hill, courtesy Death Valley National Monument Library, #2674. |

|

| Illustration 249. View from above, of lower level workings of Pleasanton Talc Mine. 1978 photo by Linda Greene. |

|

| Illustration 250. View of upper level workings of Pleasanton Talc Mine. 1978 photo by John Latschar. |

|

| Illustration 251. Lower, and older, level of workings at Moorehouse Talc Mine in 1962. The scene has changed little in succeeding years, with the exception of normal deterioration of the structures. Photo by Park Ranger Hill, courtesy Death Valley National Monument Library, #2673. |

|

| Illustration 252. View of more recent strip mining activities on upper level of Moorehouse Mine. 1978 photo by John Latschar. |

c) Ibex Springs

1. History

Desert watering holes are difficult places to interpret, and Ibex Springs is no exception. Although we know from the data that certain activities took place at Ibex Springs during certain periods of time, constant use of the watering hole by prospectors, travelers and miners for almost one hundred years has slowly erased all but the most recent signs of the past. Nevertheless, certain of the remaining structures can be identified and dated.

The first specific references to Ibex Springs were in connection with the "old" Ibex Mine of the 1880s. Unfortunately, both the mine and the spring moved around constantly in the vague geographic descriptions given in the early accounts, making it impossible to pinpoint any specific activities. Ibex Springs, however, was undoubtedly the water source for the old Ibex Mine and Mill.

During the Bullfrog boom years of the early twentieth century, references become more specific. The locators of the Lost Bethune Mine, which was in the immediate vicinity of the springs, described the area as having old arrowheads and stone cooking pots laying around, and told of the "remains of old buildings that no modern Indian could or no Mormon would build." One of these buildings, a three-sided stone structure, was converted into a bunkhouse by the miners. Subsequent descriptions of the locale in 1907 described it as a fine camp of bunk houses, boarding house, etc. Whether these buildings were constructed of stone, wood, or canvas is unknown. [10]

With the demise of the Bullfrog era mines, the small camp at Ibex Springs was deserted, and became fair play for the needs of wandering prospectors and travelers. Although we can not be certain, it is probably safe to surmise that little remained of the camp by the time the Ibex talc mines opened in the mid-1930s. Throughout the active operations of the Moorehouse, the Monarch and the Pleasanton from the 1930s to the 1950s, and the intermittent mining of the 1960s, Ibex Springs was exploited as a water source for mining and living needs, and a fairly substantial camp appeared. Since the talc mines have remained in private hands until recent years, the remains of this camp have escaped large-scale destruction, and dominate the present scene.

2. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

The talc mining camp at its height consisted of a dozen wooden buildings, including a bathhouse with plumbing, several sheds and storehouses, and several living quarters. Most of the buildings were constructed of boards and plasterboard, and had electric lights and propane appliances. The spring was improved by the talc miners by means of a concrete spring house and collecting tank, from which water was pumped or flowed to the shacks. The area is spread with numerous artifacts of very recent vintage, such as car hoods, Pepsodent toothbrushes, and a plastic Zenith radio casing. Although the buildings themselves remain in a fairly good state of repair, the proliferation of junk throughout the site makes it an eyesore.

Interspersed among the modern ruins are signs of the more removed past, such as remnants of stone walls, dugouts, and storage caves. Most of these are located in the northern part of the complex, nestled against the slope of the hills. The most important are two stone dugout/shelter ruins, consisting of three to four foot high wails, constructed of unmortered rock. Bottles in a small dump near the dugouts date the ruins to the Bullfrog era boom, and the dugout shelters were undoubtedly used as temporary shelters before the erection of the "fine camp" of the Lost Bethune Mining Company. No other surviving structures can be positively dated from the Bullfrog era.

|

| Illustration 253. Ibex Springs townsite in 1962, during last years of use. Photo by Park Ranger Hill, courtesy of Death Valley National Monument Library, #2690. |

|

| Illustrations 254-255. Top: View of typical structure of Ibex Springs townsite, showing deteriorated condition in 1978. Bottom: One of two small stone cabins on hillside to the north of Ibex Springs townsite. 1978 photos by John Latschar. |

Due to the great predominance of the scene by the modern talc mining camp, there is very little historic integrity left at Ibex Springs. The modern camp is certainly not of historic significance. The early 20th-century stone ruins have more interest, but due to a great proliferation of such type ruins throughout the Monument, and the fact that the more modern structures negate the integrity of these remains, preservation efforts are not warranted on this site. Since the older stone ruins are small, difficult to locate, and are tucked away out of sight of the rest of the camp, a policy of benign neglect should lead to no more than natural deterioration of the site.

3. Gold and Nitrate

a) Amargosa Gold Placers

1. History

In 1907, the intense gold fever which gripped the Death Valley region spilled out from the mountains surrounding the valley into the desert floor below. Following the strikes at Rhyolite, Lee, Greenwater, Gold Valley, Ibex, Harrisburg and Skidoo, anything seemed possible, for gold was being found practically everywhere a prospector stuck a pick into the rocks. Moreover, the men who searched for gold on the barren floor of the desert had a theory--one that seemed to make the discovery of riches a foregone conclusion.

In the original 1849 California gold rush, the initial finds had been in the stream beds below the mountains, where gold nuggets and flakes had been washed down from the lode claims in the mountains above. As time and experience proved, a prospector could find the original lodes by following the stream beds or geologic faults back up the valleys and mountains, until he found the source of the gold. In Death Valley, the opposite theory was proposed. Since gold had already been found in so many of the valleys and mountains surrounding the desert floor, there must be some on the floor itself, washed down through thousands of years of erosion. The only problem was to find it.

The first indication of this effort came in March of 1907, when the Inyo Register reported that over 40,000 acres of land had been located as placer claims on the floor of south Death Valley, straddling the Inyo-San Bernardino County line. Since the Register was somewhat detached from the immediate scene of the excitement, it was somewhat skeptical of the prospects, wondering what anyone expects to do with about 70 square miles of Death Valley . . .

The Bullfrog Miner, however, was much more interested. As the local paper, vitally interested in the welfare of any mining enterprise in the area, the Miner gave the erosion theory much more credit. 'It is held by scientists who have made a study of the situation that the floor of Death Valley, or the great sink which ranges below the sea level, probably contains some of the richest gold deposits to be found in the world.

The Miner reporter had undoubtedly been talking to a Rhyolite prospector, Clarence Eddy, who was the leading proponent of the new theory. "Death Valley proper," Eddy later explained in detail,

contains about 500 square miles. Within this area there is sufficient wealth to make every poor man in the world richer than Croesus; to make King Solomon's mines and Monte Cristo's treasure look like penny savings banks. It is literally composed of gold, silver, copper and lead. . .

For ages the rains and snows have been beating these mountains down into Death Valley. They are filled with the precious metals. Cold, silver, copper and lead abound here. The great quartz rocks, on account of their weight go down. Down, down, down, they have rolled for centuries! The melting snows and rains of winter keep the. surface of the basin damp throughout the season. The entire surface of the valley is composed of the highest chemical matter. There is salt, saltpetre, iron--every chemical known to science, in one form or another. Vats of vast areas have formed which are perfect quagmires of chemicals under constant action.

Well, these highly mineralized rocks, largely impregnated with the precious metals, are constantly rolling down into this cauldron of chemicals. They have been doing it for ages and centuries, as already stated. The dampness of winter set the processes to work. The hot suns of summer follow. No drugests graduate not, assayer's crucible ever performed more scientific functions!

The quartz may be seen there in all stages of decomposition. It melts under these processes like the snows in the burning sunshine above. In a few years the ore is a part and parcel of the bed of this great sink--a mixture of strong chemicals in powdered and liquid form that work on and on with the centuries, filling higher and higher the great basin that has become one of the seven wonders of the world.

For time immemorial the ores of the mountains have been rolling down into the valley; the processes have been as busy as nature itself. Gold is indestructible. It may be 100, 1000, or 10,000 feet below, but it is there, and when the process is discovered by which it may be reclaimed, all the world will be rich, and gaunt poverty will cease its weary journey in the land. [11]

Not one to rest upon his theories, Eddy had already located the most promising spots in this bed or riches. Together with F. L. Gould of Reno, Eddy had made a prospecting trip to the region during the early part of 1907. His partnership with Gould soon dissolved into competition, however, as Gould managed to secure the backing of a San Francisco operator, J. A. Benson (ironically, a man who had already been convicted of government land frauds). Gould and Benson led a party into the desert region in November of 1907, in order to test the sands and locate desirable placer claims. While the Gould-Benson party was quietly acquiring placer locations (they may be the ones who located the 40,000 acres mentioned above), Eddy was more noisily doing the same, Having obtained some capital backing from Salt Lake and Rhyolite, Eddy made a trip to the vicinity of Bennett's Well with Judges L. O. Ray and J. A. Largent of Rhyolite. Ray and Largent were convinced of the possibilities. "It would require dredgers to handle the dirt," they reported, "but it is argued that there is plenty of water--salt water--to be had at almost any part of the valley, and that machinery of this kind could be easily operated. Neither judge, however, was sufficiently convinced to put up any further, money.

Nevertheless, Eddy made another trip to the valley in December, when he located 112 placer claims in the vicinity of Bennetts Well and Tule Hole, in the name of his Salt Lake financiers. The Gould-Benson group, in the meantime, was busily surveying the valley.

The fever continued through January of the next year. Eddy staked out 1,220 acres for his company, and the Gould-Benson interests, reportedly organized as the Death Valley Placer Mining Company, drilled test holes and found water, some 300 feet west of Bennett's Well. The test holes showed returns of from 50 cents to $3.50 in gold per cubic yard of dirt, far more than enough to support a successful placer operation. Further test results in February showed returns of $2.00 in gold and 30 cents in silver per cubic yard. Encouraged by these indications, the Gould-Benson group actually ordered a dredger in order to begin mining.

Eddy, however, who felt that Gould and Benson had stolen his idea, was not having so much luck. Apparently his Salt Lake financing had fallen through, for in late February James Edmunds, of Chicago, arrived to inspect Eddy's placer claims. Edmunds, however, was not very optimistic, following a short trip to the claims. In fact, his conclusions, released to the Rhyolite newspapers, succeeded in bursting the overdue bubble. His faith, reported Edmunds, was "considerably shaken in the theory. Shattered would probably be the proper word to use in the premises . . " There may well be gold somewhere in the valley, but there certainly was none where Eddy took him. In summary, Edmunds stated, it is fooling away time to look for placers. As usual in such circumstances,one candid statement was all it took to completely bust a mining fever. Even the Bullfrog Miner sadly concluded that Eddy's theory now seemed to be based on "child-like" hopes. [12]

Eddy, however, was not so easily discouraged. Nor was Gould, who by this time had lost both his dredger and his San Francisco backers. Naturally, the two again teamed up and attempted to advance their scheme once again. Two prospectors with a theory and no money, however, could obtain no results, and the great dream of dredging the floor of Death Valley for millions in gold soon faded away.

Clarence Eddy's dream, though, was hard to kill. In 1932 and 1933, during the depression, prospectors again flooded the west, searching in desperation for that one quick discovery which meant instant wealth. Again, the floor of Death Valley was not ignored. Six miles northwest of Saratoga Springs, an unidentified group dug shafts and drill holes, testing for placer gold. 1,500 samples reportedly turned up gold to the value of 55 cents per cubic yard, but no production resulted, due to difficulties in devising a method of recovery. At the same time, a group headed by one T. A. Rhodimer, working in essentially the same area as had the Gould-Benson group, claimed to have uncovered over 100 million cubic yards containing in excess of $1.00 in gold per yard. When a potential developer, the Natomas Company, sent out an expert in the fall of 1938, the old story was repeated. The experts tests showed only traces of very fine gold, and the scheme collapsed.

In 1958, the dream was reborn once more. The Mineral Productions Company of Colorado acquired leases on the same seventeen sections of ground northwest of Saratoga Springs, and again initiated tests. Although they reported assays from a trace to over $1100 per yard--with an average of around $1.00--every type of drilling equipment which was tested failed in action. In 1959, the American Zinc, Lead and Smelting Company investigated the area, but soon quit, as did Transworld Resources. Thus, despite glowing reports in at least one mining journal, and the claims of the Minerals Production company that 98 percent of the gold was recoverable by cyanidation, no serious attempts towards actual mining got off the ground. [13]

Following the flurry of 1958-1959, no further attempts were made to open placer mines in south Death Valley. Another hopeful prospector did file claims on thirty-two locations in the fall of 1973, in essentially the same area tried by Benson and Gould in 1907 and Mineral Production in 1953. As could be expected, recording of locations was the nearest he got towards actual mining.

2. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

Due to the nature of these abortive placering attempts on the floor of the valley, absolutely no physical clues remain to help locate the precise areas where these activities took place. The early placer claims were made in two areas: the vicinity of Bennett's Well, and the general area northwest of Saratoga Springs, along the Inyo-San Bernardino County line. More precise locations, however, are impossible. Obviously, no historic structures of any significance are in the area concerned.

There is, though, an excellent interpretive opportunity connected with this story. A feasibly located interpretive sign, placed somewhere along the road leading to or through south Death Valley, would have a decided impact upon tourists. Perhaps nothing could better impart the real meaning of gold fever than to stand in the heat of the valley, staring across the shimmering floor of the sink, trying to comprehend the dream of the men who thought it possible to float a dredger in the middle of that wasteland.

b) Amargosa Nitrate Mines

1. History

The history of nitrate mining in south Death Valley is very similar to that of the gold placering attempts. Both types of mining activity were in the same general region, both left little or no traces on the land, and neither resulted in any production at all.

Attempts to find nitrate in the area, however, predated those of the gold hunters. As early as 1892, a mining engineer named J. M. Forney issued an ambiguous study of nitrate claims in the area roughly fifteen miles northeast of Saratoga Springs and fifteen miles southeast of Shoshone--outside the present Monument boundaries. In 1896, several groups of prospectors recorded large claims of from 1160 acres to 2,760 acres in this region, but no further activities took place. [14]

The first--and only--true rush to the area was in 1902. Again, the rush was the result of a promising report, this time by the California State Mining Bureau. Its Bulletin 24, published in the summer of 1902, described in glowing detail no less than eight niter fields in the south Death Valley region, totaling some 32,000 acres. In the opinion of a modern geologist, the "erroneous assertions" made by this report have been responsible for raising unjustified hopes from 1902 until today.

But the damage had already been done, and the rush was on. Of the eight fields described in the report, four were all or partially within the present-day borders of the Monument. Contemporary descriptions are vague, but it is evident that much of the ensuing pandemonium took place within the confines of the park.

The San Francisco Chronicle was the first paper to report the beginnings of the grand rush. In October of 1902, 900 men were reported either in the valley already or poised to make the rush. In an interview with a gold prospector, who professed not to be interested in niter, the following was excerpted:

is there niter there? There is enough niter in Death valley to make it a center of population and life instead of the center of desolation and death that it has long been. Tens of thousands of men will be employed. Railroads will be run into the valley from all points. From what I have seen and learned I should say that Death valley will prove to be the rival of Chile as a producer of niter.

Within a week, however, the bad news come in. On October 13th, an official of the Geologic Survey denounced the rush:

. . . There is, in my opinion, not the slightest chance that anybody going in to locate nitre will make a dollar. The demand for saltpeter is comparatively small, taking all manufactoring, mining and medical and chemical uses, including gunpowder manufacture, and the market is held at present by a trust that controls all the saltpeter to fill all the demand in sight.

In strikes me as a little short of insanity for the average miner to go into Death Valley to locate nitre claims. I have been through Death Valley and know what such a trip means. So far as profit is concerned they might well make a rush on Salton basin and locate salt claims. [15]

The geologist was undoubtedly correct. Either due to his more pessimistic statements, or to the inevitable disappointment of prospectors already on the scene, the rush faded as quickly as it had appeared. Very few of the prospectors even had enough hope left to bother recording any claims which they might have made.

Following the grand rush of 1902, more desultory efforts in the niters beds of south Death Valley appeared from time to time. In the fall of 1905, it was reported that the state government was inspecting the beds, and again in April of 1906, the unconvinced California State Mineralogist called attention to the possibilities of the region. In 1907, two companies, the Pacific Nitrate Syndicate, and the American Niter Company, ran tests in the area. The Greenwater Times and the Greenwater Miner reacted to the news in the manner to be expected of Greenwater papers, claiming that the "largest powder works in the world are to be established at the southern extremity of Death Valley." Even the Bullfrog Miner scoffed at that.

The Pacific Nitrate Syndicate ran fairly extensive tests in the area during the next year or two, and had enough employees on the spot during 1909 to warrant the erection of several tents and frame buildings at Saratoga Springs. When the tests proved futile, one of its employees, A. W. Scott, Jr., filed on 160 acres of niter claims in the immediate vicinity of Saratoga Springs, and continued the efforts for a short time. Scott was also kind enough to leave behind a photograph album, Niter Lards of California, depicting life at Saratoga Springs in 1909 and 1910. [16]

Further study of the areas niter beds was undertaken by the U.S. Government in 1912 and 1914, and by the California Nitrate Development Company in 1914 and 1916. The only concrete results of all this study and testing were recommendations that further tests and studies be made. Finally, in 1922, the USGS issued the definitive report of the niter deposits of the region. Eleven deposits in and near south Death Valley were exhaustively studied, including the two major deposits within the Monument boundaries: the Saratoga bed, lying south and southwest of Saratoga Springs, and the Confidence bed, running ten miles north and south of a point directly opposite of the Confidence Mill site.

The results of these studies effectively put an end to nitrate prospecting in Death Volley. Speaking in general of the entire area, the report concluded that

Nitrate salts in extractable quantities have been found in the deposits described in this report, but considered in relation to the needs of the country, even for a very short period during the emergency of war, these deposits were not regarded as of immediate practical importance, because of the relatively high cost of any known method of collecting and extracting such nitrate in a commercial form, as compared with the cost of getting the nitrate from Chile.

More specifically, the Saratoga deposits were considered "too small to be worth consideration as a source of nitrate even under war conditions," while the "most abundant sort" of niter found in the Confidence field was "too poor," and "the richest is too scarce, to be exploited commercially." Thus died the niter mines of Death Valley, without ever having produced. [17]

|

| Illustration 256. Niter lands of California--this was the desolate country which attracted the great nite rush of 1902. Photo from "Niter Lands of California," courtesy Death Valley National Monument Library, #3083. |

2. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

Again, like the gold placers of the same region, the nature of the activities involved in niter prospecting left little or no visible scars on the ground. True fanatics, armed with accurate and specific maps and research data, will be able to find various cuts and trenches scattered throughout the area, but absolutely no remains of historic significance will be found.

The short-lived camp at Saratoga Springs connected with niter prospecting will be discussed in the Saratoga Springs chapter below.

4. The Saratoga Springs Region

a) Saratoga Spring Area Talc Mines

1. History

Shortly after the discovery of talc mines in the Ibex Springs region, several more talc deposits were located to the south, in the hills north of Saratoga Springs. The first of these was the Ponga, a single talc claim about three miles north of Saratoga Springs, which was located by Ernest Huhn in the mid-1930s. After sinking a small shaft, Huhn depleted either his capital or his desire to develop the claim (or perhaps both), and it lay idle until 1948, when it was eased to the Southern California Minerals Company. This company worked the deposit from 1948 to 1955, obtaining 12,554 tons of commercial talc. The Ponga has been idle since 1955, and is now owned by Pfizer, Inc.

The Superior Mine, located in the midst of the hills north of Saratoga Springs, was the next to be developed. Consisting of three claims, this mine was owned and operated by the Southern California Minerals Company from its beginning in 1940 until recent years. The Superior Mine was easily the most developed and most productive talc mine in the southern Death Valley region, producing 141,000 tons of ore during its most active period, 1940-1959. The Superior remained in intermittent operation through the early 1960s. Its now dormant facilities are owned by Pfizer, Inc.

Adjacent to the Superior is the Whitecap Talc Mine, also owned and operated during its active life by the Southern California Minerals Company. Consisting of a single body of ore, the Whitecap was worked between 1947 and 1951, yielding 6,315 tons of ore. The mine has not been operated since 1951, and is now the property of Pfizer, Inc.

|

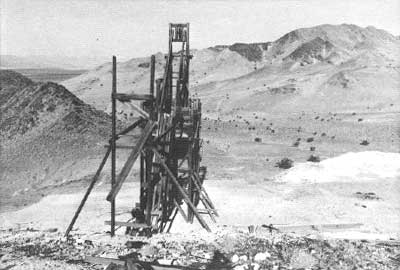

| Illustration 257. Map of the Northwest portion of the Avawatz Pass Area. |

To the southwest are the three groups of workings known collectively as the Saratoga Mine. The northern group of this complex was opened in 1944 and worked for one year by the Champco Minerals Company, which extracted about 1,000 tons of ore. After lying idle for several years, the Saratoga complex was leased by the Southern California Minerals Company, which opened new bodies of talc in the south group in 1949. These were worked for several years until being abandoned in 1954, having produced only small amounts of talc. Finally, in 1955, the central group of claims was opened by the Southern California Company, and intermittently operated until the mind-1960s. As a combined total, the output of the three groups of the Saratoga Mine are estimated as having produced 5000 to 10/000 tons of talc. All the Saratoga holdings are now idle, and are in the possession of Pfizer, Inc.

During the active phases of these Saratoga Springs area talc mines, ore was hauled by truck to various railroad points for shipment to processors in Los Angeles and Ogden, Utah. The usual shipping point was Dunn Siding on the Union Pacific Railroad, about 28 miles southwest of Baker, California--a point approximately 64 miles from the mines. [18]

2. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

As a group, the Saratoga Springs talc mines closely resemble those of the Ibex Springs area. At the Ponga, which was essentially a lode operation (with a minimum of bulldozer exploration and assessment work), there is a wooden ore bin, a collapsed wooden headframe, an engine house foundation, and two shafts. All of these structures are in poor condition, and none possess any historic significance.

The Whitecap site contains only a wooden headframe and ore bin, but both are in excellent condition. The Saratoga groups contain the usual assortment of wooden ore bins, headframes, tramway remnants, and foundations-in various stages of deterioration. As in the case of the Ponga, both the Whitecap and Saratoga were essentially shaft and lode operations, with a minimum of bulldozer stripping carried on in the later years of development.

There is not much to differentiate between the Ponga, the Saratoga, or the Whitecap. The wooden mining remains are relatively intact and most are in good shape, probably because all three mines were operated by the same company, which refrained from stripping abandoned sites, in case of future developments. As in the Ibex Springs area, a policy of benign neglect is recommended. There is certainly nothing within these sites to warrant the utilization of preservation money, and their remoteness from general tourist traffic will probably preserve these remains with only a usual amount of natural deterioration.

The Superior Mine, reflecting its greater period of production, has more extensive structural remains. These are, however, of a more modern period than found elsewhere in the region, and consist of tin and frame living shacks and mine buildings, as well as a steel headframe. In a mining sense, this site is the most important one in the area, but it is also the most unsightly and the least historic. Judging from the condition of the camp, operations in the last years were carried out on a shoestring budget. As a result, the area today resembles a modern garbage dump more than a possible historic site. When the underground talc lodes ran out, the company resorted to stripping operations before giving up, leaving the area pitted with large and small gouges and holes, and destroying the possibility of interpreting the earlier years of activity. This general condition of the site, coupled with the modern flavor of the remaining structures, makes the Superior mine unworthy of any preservation efforts.

|

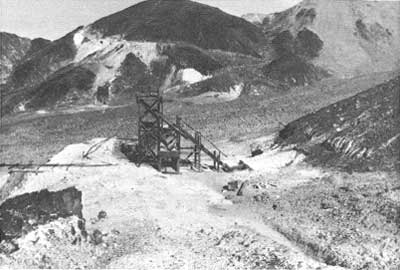

| Illustration 258. Partial view of the Superior Talc Mine workings, showing steel head frame, steel frames for abandoned buildings, and dumps. 1978 photo by John Latschar. |

|

| Illustrations 259-260. Top: Ruins of short-lived Ponga Talc Mine, overlooking south Death Valley. Bottom: Wooden headframe and hoisting works of Whitecap Talc Mine. 1978 photos by John Latschar. |

|

| Illustration 261. Saratoga Talc Mines: View from middle group of workings north towards northern group. 1978 photo by John Latschar. |

|

| Illustration 262. Saratoga Talc Mines: View of southern group of workings. 1978 photo by Linda Greene. |

b) Saratoga Springs

1. History

Like Ibex Springs to the north, activities at Saratoga Springs have been constant and varied over the last hundred years, for the springs have long been the most important watering spot in the south Death Valley region. As with Ibex Springs, little remains to bear witness to Saratogas past, due to the destruction wrought by years of harsh weather and the sticky hands of generations of prospectors and travelers.

The first printed mention of Saratoga Springs is connected with the 1871 Wheeler survey. Although accounts are somewhat contradictory, a portion of the Wheeler party apparently camped at the springs, and named them after the well-known resort of Saratoga Springs, New York. Whether or not the springs were first discovered by Wheelers party, they soon became known to travelers, teamsters and prospectors of the desert region, and were important desert stops for all. Although the accounts again vary, the springs were a primary watering hole for the famous 20-mule team borax wagons during the 1880s, as they were on the direct route from the old Amargosa borax works, and the alternate route for the Harmony borax works of Death Valley. [19]

After the borax works were closed in the ate 1880s, the springs reverted to the occasional use of prospectors and travelers, until 1902, when the mad nitrate rush began. These rushers left almost as soon as arrived, however, and the springs were quiet again until the reverberations of the Bullfrog boom reached down into south Death Valley. Then, in 1905 and 1907, occasional references were made in the Rhyolite newspapers to gold and silver miners who had prospects nearby. None of these prospects panned out, and activity around the springs soon declined. In 1909 the niter prospects were again investigated, and due to the efforts of A. W. Scott, we have a pictorial account of life at the Saratoga Springs mining camp. But Scott's camp only lasted a year or two, and the springs area was subsequently deserted. The only visitors for the next twenty-odd years were lonely prospectors and tourists, who slowly but surely dismantled what had been left behind by earlier occupants. A 1921 visitor saw no signs of life in the vicinity of the springs. [20]

In the 1930s, with the opening of the Saratoga district talc mines, the springs once more became an important source of water. Throughout the life of the Ponga, Superior, Whitehouse and Saratoga mines, all water for the daily use of the mines and miners (with the exception of drinking) was drawn from Saratoga Springs. At the same time, a small resort and water bottling effort was carried out by a local entrepreneur. World War II killed the resort, due to gas rationing, and the water bottling business soon followed suit. The mines were slower to die, and continued to draw upon the Spring waters until the 1960s, when they finally closed. [21]

|

| Illustrations 263-264. Top: Stone cabin built ca. 1890, converted to blacksmith shop in 1909 by Pacific Nitrate Company. Photo from "Niter Lands of California," courtesy Death Valley National Monument Library, #3076. Bottom: Same site, 1978. Photo by Linda Greene. |

|

| Illustration 265. Pacific Nitrate Company's camp in vicinity of Saratoga Springs, at its height ca. 1910. Photo from "Niter Lands of California, courtesy of Death Valley National Monument Library, #3104. |

|

| Illustration 266. Second stone cabin, Saratoga Springs area, probably built by Pacific Nirtrate ca. 1909, may be seen through framework of cabin under construction. Photo from "Niter Lands of California, courtesy of Death Valley National Monument Library, #3092. |

|

| Illustration 267. Spring house at Saratoga Springs, undated, ca. 1930. Note tourist accommodations in right background. Photo courtesy Death Valley National Monument Library, #1563. |

2. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

Little remains upon the site of all this activity. While this is not unusual for a desert watering hole, the situation at Saratoga Springs is further confused by conflicting data concerning the two principal remaining structures--the remnants of two stone cabins.

O. A. Hutford, a compiler of popular lore, wrote that in 1901 there were two old stone houses at the springs, built in the 1890s, and used as a saloon and a store for the borax teamsters. A. W. Scott, however, in his photograph album "Niter Lands at California," labeled one of the structures as a stone house built by a "one lunger" about 1889, who lived there for two years. Scott's niter company converted the stone house into a blacksmith shop.

Scott's pictures, taken between 1908 and 1909, also show halt a dozen tent and frame structures built in the vicinity of the springs during that period, including a store and a spring house. Although it is not certain, the spring house appears to be the one used by the Saratoga Water Company in the 1930s.

Unfortunately, through the depredations of time, weather, and economic talc miners, no remnants of the frame or tent structures built by the niter company are now visible. The only extant structures at Saratoga Springs are the slowly crumbling walls of the original two stone houses built sometime prior to the turn of the century. The smaller of these is little more than a pile of rubble, but the larger one is still partially intact. Constructed of unmortered stone, with dimensions of nine feet by twelve feet, the three to four foot high waits of this ruin are clearly discernable. [22]

Due to its sensitive location, just north of the fish pool at Saratoga Springs, the site of these stone ruins should be subject to a policy of benign neglect. Although they are a part of an interesting site, the ruins do not justify preservation or stabilization funds, but should be protected against vandalism, and made a part of the interpretation of the long history of Saratoga Springs.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

deva/hrs/section4d.htm

Last Updated: 22-Dec-2003