|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION IV:

INVENTORY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES--THE EAST SIDE

C. The Black Mountains

1. Introduction

As the reader is by now undoubtedly aware, the history of the entire east side of Death Valley was dominated by the great Bullfrog boom. This influence, which we have already seen in the Bullfrog Hills and the Funeral Range, was no less evident in the Black Mountains, to the south of the Funeral Range. Like the above territories, the history of mining in the Black Mountains is dominated by the story of various and sundry booms and busts, all subsidiary to the Bullfrog boom to the north. At a glance, therefore, the history of the mines and mining camps in this section is not too different than those related above. But there were two distinct phenomena which showed up in this section. Although neither of these are particularly surprising on their own rights, they both emphasize telling points concerning the success or failure of desert mining camps.

The first was the amazing stampede into Greenwater. That spectacular rush will be described in more detail later, so it suffices to point out here that in Greenwater we see the final culmination of the unbelievable boom spirit which had been prevailing in the desert mining camps since the discovery of Tonopah in 1900. Since that discovery, scores of boom towns had been added to the map in southern Nevada and southeastern California, and each seemed to proclaim to the world that the new era of mining booms was here to stay. Untold riches were buried beneath the desert floor, and all one had to do was dig almost anywhere to secure a fortune. That spirit reached its height in conjunction with the Greenwater stampede--and the subsequent Greenwater bust marked the beginning of the decline of the early twentieth-century mining booms.

|

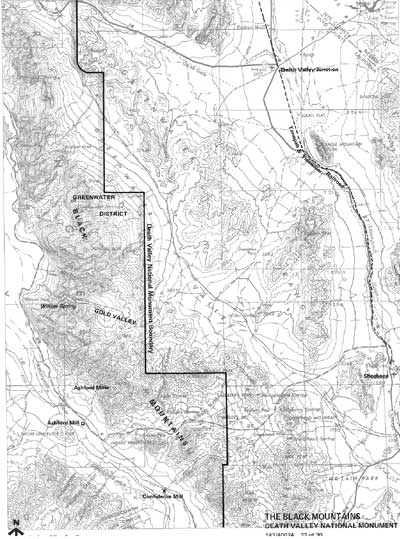

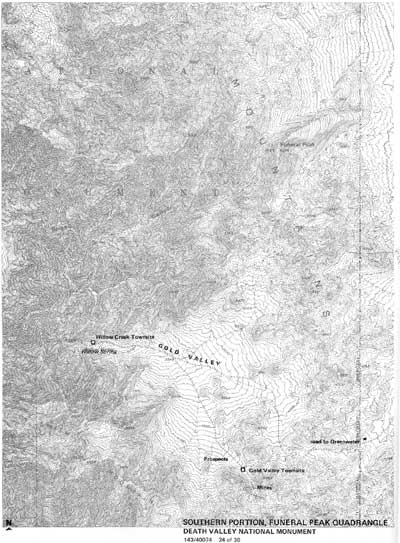

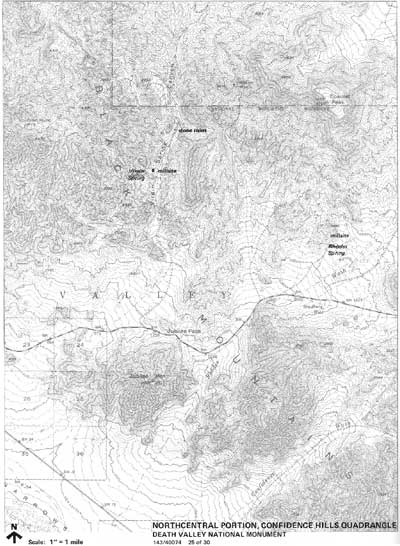

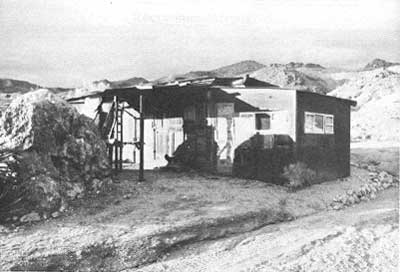

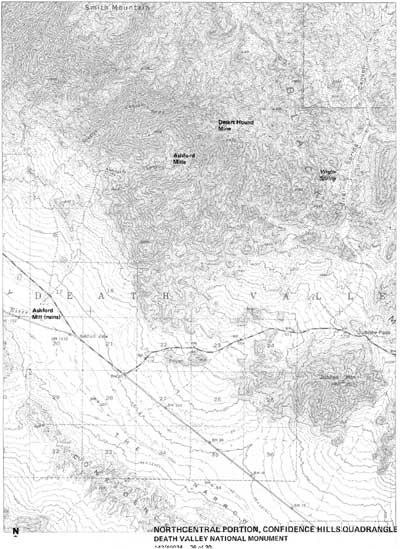

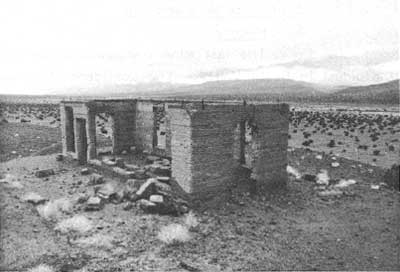

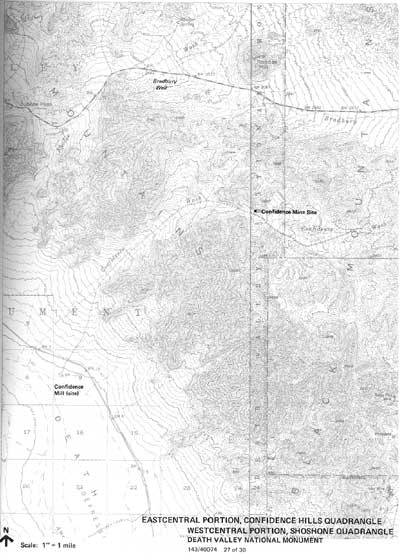

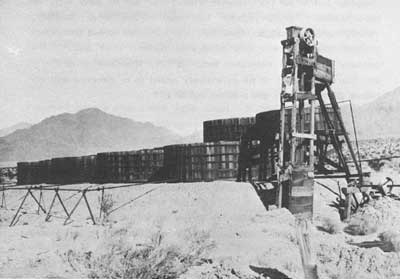

| Illustration 189. Map of the Black Mountains. |

On a less psychological note, the mining camps of the Black Mountains also pointed out quite clearly the ever-present handicaps against which desert mining camps were forced to struggle--the search for water, fuel and transportation. At the time of the mining booms in the Black Mountains, Rhyolite was far and away the largest supply center in the entire Death Valley region, and the farther south one moved from Rhyolite, the more expensive food, fuel and supplies became. Thus the farther one moved from Rhyolite, the more expensive it was to open a mine, and the richer one's ore had to be in order to reap a profit. In addition, the fact that water sources grew fewer and farther between as one moved south multiplied the problems of expenses and even survival. Mines, in short, which would have become producers in the Bullfrog Hills were totally unprofitable in the Black Mountains. These dual problems of water and transportation are the constant factors in the determination of the success or failure of mines in this section.

On an entirely different note, it seems fitting to give the reader a word of warning at this point. This study has been based heavily upon the accounts of mines as printed in contemporary mining camp newspapers and national mining journals, neither of which sources are completely reliable, Mining camp newspapers were always wont to emphasize the positive and ignore the negative in their reporting, for the success of the paper depended upon the success of the camp. Thus, as we have seen time after time, mines which are reported to be healthy, productive and rich in one issue of a paper are suddenly closed by the time the next issue hit the street, without a word of explanation from the friendly editor. National mining journals, while more prestigious, are hardly more reliable in their weekly coverage, since the great majority of their news came from the editors of local papers, who served as stringers for the national syndicates.

But the editors and papers should not totally shoulder the blame, for they in turn relied upon the mine owners and superintendents for their information. With this in mind, the following article, which appeared in the Inyo Independent in 1882, should be enough to emphasize the dangers of relying upon such biased sources for information concerning a mine:

Recently, says an exchange, a Nevada man invented a lying machine, and went around trying to sell 'em. The machine was warranted to trot out a first-class lie on any subject, at a moment's notice. But it didn't sell well. He took it to an editor. Said the editor: "Come, you get out of this. I tell the truth in my business." The inventor presented it to a lawyer, but he also looked horror-stricken and offended. A fishing party looked hankeringly at it, but their language was to the effect that they abhorred untruth. At last the disheartened inventor tried a mining superintendent, who flew mad in a minute. "You scoundrel," he cried, "do you mean to insult me?" "No," tremblingly answered the man. "Then what in blazes do you mean by offering me that thing?" "Why I--I thought you might occasionally want to use it in your business." "You wretch, what do you take me for?" "Oh, sir, I didn't mean to insinuate that you could tell a lie." "That's it " cried the superintendent; "that's what I'm mad about. You conceited ass, you think you're able to invent a machine that I can't lie all around, and that without an effort. I never was so insulted in all my life! Get!" And he immediately set to work writing his weekly reports.

Since this type of reporting was more evident in Greenwater than in any other boom camp in Death Valley, a word to the wise should be sufficient.

2. The Greenwater District

a. History

Greenwater Valley was the site of the most spectacular boom in the history of Death Valley mining. While other districts, such as Bullfrog, Lee-Echo, Panamint, Skidoo and Leadfield had their booms, which saw rushes into new mining areas and the establishment of new mining camps and towns, Greenwater surpassed all the others in the brilliance of its birth. Within a year and a half from the beginning of the rush to Greenwater, the deserted desert was home to over two thousand inhabitants in four towns, seventy-three incorporated mining companies, and was the focal point of over 140 million dollars worth of capitalization.

But it was not only the amazing rush to Greenwater which sets it apart from other booms, for Greenwater also experienced the shortest life ever recorded for a boom camp of its size. Within one year from the height of the boom, all but five of the companies had left the district, and Greenwater was practically deserted. By the end of two more years, everyone had given up, and the Greenwater Valley, the scene of so much bustle and excitement a short time before, was once again completely deserted. This combination of a tremendous boom, a brief life and then complete desertion, all within the space of less than four years, has made Greenwater a name which is still anathema to the investing public, and dear to the hearts of desert folklorists. Few, if any, mining camps in the American west have ever combined such initial excitement with such total disappointment.

Inevitably, considering the popular place of Greenwater in the annals of western folklore, it is sometimes difficult to separate the fact from the fiction surrounding the history of the district--and there is no lack of either. Although the argument about who really discovered Greenwater started as early as 1906 and has continued ever since, it seems apparent that the honor must be divided. Some prospectors later claimed that they had made copper locations in Greenwater Valley as early as the late 1890s, but the obvious difficulties inherent in mining copper in an isolated spot caused such locations, if made, to be abandoned.

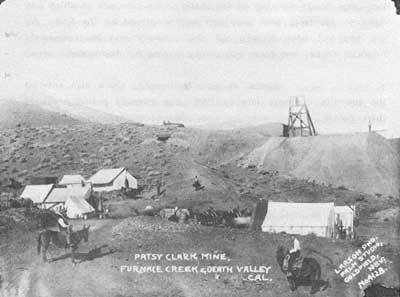

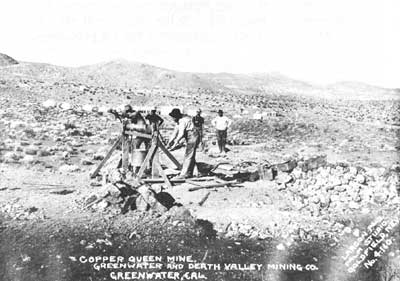

The real discovery of Greenwater, as with most throughout the Death Valley area, came about as a result of the Bullfrog boom, sixty-five miles to the north. As noted before, the great rush to the Bullfrog Hills soon filled up the ground in that vicinity with location notices, and late-arriving prospectors were forced to move farther afield. Two such men, Fred Birney and Phil Creasor, ambled south down the east side of the Black Mountain Range, and in February of 1905, while looking for gold, uncovered rich surface croppings of an immense copper belt in Greenwater Valley. Birney and Creasor sent samples of their find to Patsy Clark of Spokane, a well-known copper mining operator, and Clark was sufficiently impressed to buy the claims from the two men in May.

Hearing of Clark's new holdings, which held amazingly high copper values at the surface, F. August Heinze, the "famous copper king" of Butte, Montana, also visited the new locations, and was equally impressed. The rich surface showing was so promising that Heinze and his partners immediately bought sixteen copper claims from another pair of early prospectors for the neat sum of $275,000. Commenting upon the transaction, which brought newspaper attention to the area, the Inyo Independent reported that the "vast copper deposits in the Funeral [sic] range have long been known to prospectors, but their inaccessability to the markets prevented working." Now, with the booming camp of Bullfrog to the north, and the promise of railroads into the desert regions, the transportation and supply problems would be much less severe, although the Greenwater Valley was still a long way from civilization.

As the news quickly spread that two of copper's biggest operators had located in Greenwater, a mile rush ensued. Prospectors and mining men started to flock into the Greenwater area in order to stake out close-in ground. As usual with a new boom, transportation problems exceeded all others, and many prospectors, including one who reported for the Inyo Independent were reduced to walking from Bullfrog into the new district, a task which took three days. The work was rough, since even in September the thermometer reached 113 degrees in the afternoon, and the reporter-prospector found that he was forced to sit down and rest after building each monument to mark his claims. The heat was not alleviated by the total lack of water in the district, and prospectors who ran out of water were forced to leave their location work and return to Bullfrog, the nearest point of civilization. [1]

By late June of 1905, Patsy Clark already had eight men working at his property, and a shaft had been sunk thirty-five feet into the ground. As the year progressed, other operators entered the scene, including Arthur Kunze, who secured some of the best looking ground in the area and had five men working it by the end of the year. As 1906 opened, Kunze, Clark and Heinze began to have plenty of company, for innumerable other mining promoters, prospectors and miners were entering the district. Clark established a mining camp near his mine to support his operation, and other small camps sprung up along the valley floor as mires began to open almost daily.

|

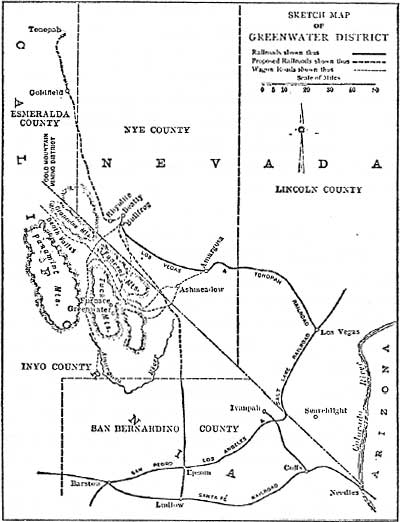

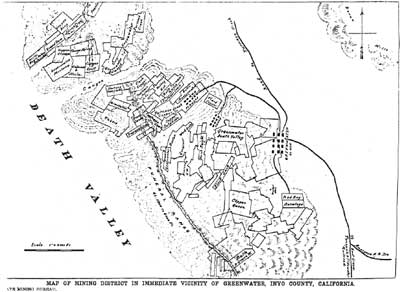

| Illustration 190. A somewhat inaccurate map, published in late 1906, which nevertheless shows the relative distances involved between Greenwater and Rhyolite and Amargosa, its two main supply points. |

As the rush to the area continued, however, it soon became apparent that the lack of an adequate water supply anywhere in the vicinity would be a major problem. "The water proposition is the serious drawback in that section at present, and will be a matter of considerable expense," remarked a Rhyolite stock broker, "yet the earmarks of the country seem to show that any expense would be justified, judging from the surface indications." Those surface indications were were indeed so rich that men and money continued to rush into the district, regardless of the serious problems of water and transportation. As the spring progressed, some of the biggest names in Nevada mining joined the boom, and fortunes reaped in Tonopah and Goldfield were reinvested in the promising new district.

"All of the great copper magnates are looking to this section," reported the Inyo Register in May, "which is destined to become the next great copper district of the world." That prediction seemed to be borne out by June of 1906, as the copper belt was "proven" to be at least seven miles long. Four of the larger mines had by now been incorporated into full-fledged mining companies, and Greenwater seemed assured of a long and lively life.

The rush slowed down somewhat during the hot summer months of 1906, although the future of the district looked even better when both the Las Vegas & Tonopah and the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroads, which were building into the Bullfrog District, expressed interest in tapping the new copper belt into the south. The local papers declared that the district "will make one of the greatest copper camps in America," and the continuing rush caused the major national mining journals to take notice of the area. "The weather in Death Valley is the only thing that prevents Greenwater from having one of the biggest booms on record in this country," wrote the Bullfrog Miner. "But even the midsummer heat of the "terrible region" does not keep prospectors out. Hardly a day passes that Bullfrog prospectors are not seen starting out for Greenwater." in early July, a stage line was started from Ash Meadows into the new district, and water, which was being hauled in from fifteen miles away, was selling for $5 per barrel. [2]

During one week of July, seven different properties were bought and sold in Greenwater, and by the end of that month, the demand for surveying and assaying support for the prospectors and promoters was so great that two offices had been established in the district. Over fifty miners were working for the five companies which had started sinking by the end of July, innumerable others were combing the hills for promising locations, and the Greenwater Miners Union was organized. A crude road from the Rhyolite area had been carved out, which cut travel time to five hours by auto, but still the water problem plagued the development of the district. In addition, so many claims were being located, sold, exchanged and relocated that inevitably conflicts began to arise between claim holders.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars had changed hands by the end of July, as feverish trading of mines and claims took place. Five mining companies were organized, and the capital stock of four of them reached the figure of $5,750,000. "This week auto after auto loaded with prospective investors has gone to Greenwater, and the demand locally for horses and rigs has almost exceeded the supply," reported the Bullfrog Miner. The rush was causing scarcities in Greenwater, and water rose to $7.50 per barrel, while horse teed was almost as hard to find. But the rush continued, and "As is usual in new Nevada mining camps the townsite epidemic has broken out in a decidely virulent form. No less than three towns are already planned, and it is a difficult matter at this time to tell which is going to be the commercial center of the district. That there will be a flourishing town in the district goes without saying, but which and where it will be is a matter of conjecture at this writing. It has the most observing man guessing."

As more and more prospectors flooded into the area, concerns began to arise over their welfare. Printed warnings were published in the Rhyolite papers, warning prospectors to bring all the food and water they would need into the district with them, since none could be provided there. Water was being hauled from Furnace Creek in Death Valley, but "Teams making the trip to the creek and back, fifty miles, drink about as much as they can deliver, making it almost impossible to get any reserve supply. Unless travelers heed the timely warning there is liable to be real suffering, and perhaps a number of deaths," Several mine owners, who were importing water to meet the demands of mining and to supply their employees, publically warred prospective visitors that they could no longer afford to sell water to private individuals.

But despite all these serious problems, there was no denying the allure of the Greenwater District, and the rush continued in August. By this time, the district was beginning to take shape, competing towns had been surveyed and platted, and one of them had established a boarding house. On July 29th, a meeting was held to organize the new district, in order to alleviate some of the problems caused by conflicting claims, and to remove the necessity for prospectors to travel all the way to Independence, California, to record their claims. The population of the district was now estimated at 300, and several stores and a restaurant had opened for business. Kimball Brothers, the staging kings of Rhyolite, announced a new stage line which would make thrice-weekly trips into Greenwater, and one traveler counted over 100 freighting wagons heading towards the district in one day, straining their resources to supply the growing demands of the new boom camp. Canned tomatoes were an especially popular item for sale at the crude tent stores, since they were cheaper than water, which was now selling for $10 a barrel, and quenched the thirst almost as well.

The rush to the new region had several unique aspects, which the local newspapers were quick to spot. Due to the extremely rich surface showings, money was pouring into the district at a tremendous rate, before ground was even broken. As the Rhyolite Herald noted, money seems to have beat labor to the scene of activity, as the big capitalists were on the ground and buying claims when no work has been done. It is not a poor man's region," agreed the Bullfrog Miner, "but one which will require a great deal of money to develop it."

All this business, of course, was good for the Rhyolite area merchants, and the new boom was looked upon favorably. "All Nevada is taking a hand in this rush," noted the Inyo Independent "as practically the whole of the United States has been told of its marvelous deposits of copper, which are revelations to geologists and mining men in general. Although the district hardly needed another spur to its boom, it got one anyway on August 10th, when the organization of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was announced. Promoted by Charles Schwab, the steel and mining millionaire whose name was magic to Nevada miners, the new company was incorporated for $3,000,000, and together with Patsy Clark's Furnace Creek Copper Company, assured "a thorough and complete development of the district."

By the middle of August, the townsite rivalry was beginning to take shape, as two major competitors emerged from the dust. Arthur Kunze was the chief promoter of the first, and his town seemed to have the edge. Alternating between the name of Kunze and Greenwater, Kunze's townsite was located midway between the mines of the Furnace Creek Copper Company and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company--the districts two largest mines. By mid-August, Kunze's townsite boasted of two stores, and a hotel, a restaurant and several corrals were under construction. The Salsberry Water Company was under contract to Kunze to keep the camp supplied with water, and a petition was sent in for the establishment of a Post Office.

The Kimball Brothers obligingly routed their stage line to Kunze's townsite, and the Tonopah Lumber Company, in addition to establishing a lumber yard to supply the hectic construction pace, sent down several 12-horse teams, to be used in hauling supplies from Johnnie Siding of the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad to the new townsite. The lumber company, in addition, supplied a 2,500 gallon water tank for the townsite company, and Kunze's plat of the town, which showed thirty-two blocks with over 550 lots for sale, was approved by the Inyo County Commissioners on August 13th. Assessing the situation, the Bullfrog Miner predicted that Kunze's camp seemed to have the inside track over it main rival, the townsite promoted by Harry Ramsey.

Just to add to the confusion, Ramsey also insisted on calling his townsite Greenwater, although it was commonly called Ramsey, and less commonly called Copperfield. Whatever it was called, its location was hard to pin down, since it was variously described as being one to four miles east or southeast of Kunze's camp. Nor did Ramsey help alleviate the confusion when he moved his site around at least once. Nevertheless, Ramsey vigorously promoted his own town, and even tore down his iron office building at Rhyolite and moved it to Greenwater-Ramsey-Copperfield.

As the rush continued, one observer counted $25,000 worth of supplies heading into the Greenwater District in one day, and another counted 200 miners and prospectors in the area, not including those who were out in the hills surrounding the camps. The Engineering Mining Journal assessing the Greenwater boom, noted that the "copper finds there recently have brought about an excitement equal to that at Bullfrog two years ago. Hundreds of people from Tonopah, Goldfield, Lida, Palmetto and the Bullfrog towns are traveling towards Greenwater in all sorts of conveyances. As high as $200 is being paid to automobile companies for transportation by wealthy operators who are anxious to get in early."

But getting into Greenwater was not that easy for those who could not afford the $200 to rent an auto. Those who arrived by train via Johnnie Siding could sometimes hitch a ride on one of the big freight teams constantly traveling between the railhead and Greenwater, but that trip took from twelve to fifteen hours. The Kimball stage took just as long, for the relatively reasonable rate of $18 per passenger, but spaces were limited, and numerous travelers found themselves forced to wait at Johnnie Siding for a day or two before their turn on the stage came. One migrant described his trip to the Bullfrog Miner, "It's a fright of a trip; 55 miles from Johnnie siding,; sand most of the way. Stage leaves Johnnie siding 3:00 p.m.; had supper at Ash Meadows; camped for the night 10 miles this side of it." Once arrived at Greenwater, the situation was not much better. "About 70 to 100 men here and about 100 gallons of water, 15¢ per gallon. Meals $1 transiently, regular 1.50 a day. Store and a restaurant here and about a dozen tents. The camp is on Kunze's ground. Clark [Patsy Clark's mining camp, also known as Furnace] is about 2 miles west and Ramsey 2 or 3 miles east"

|

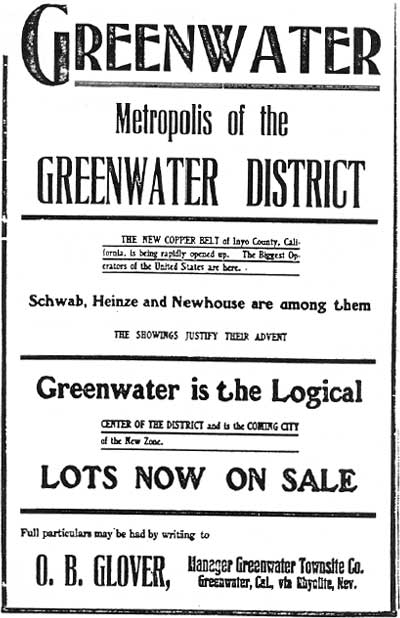

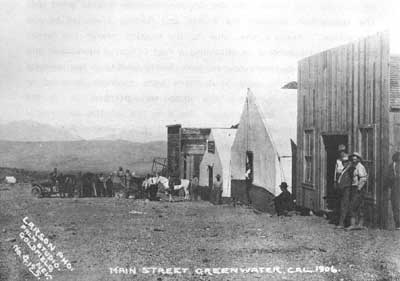

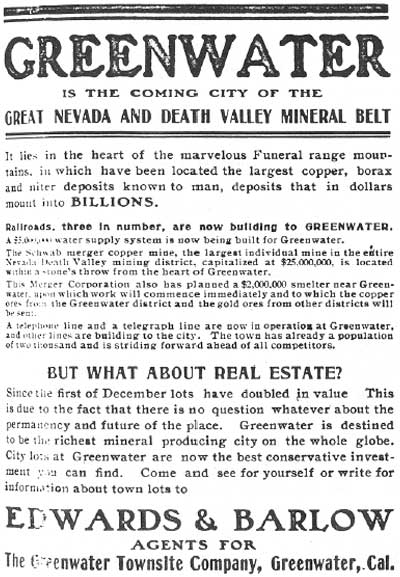

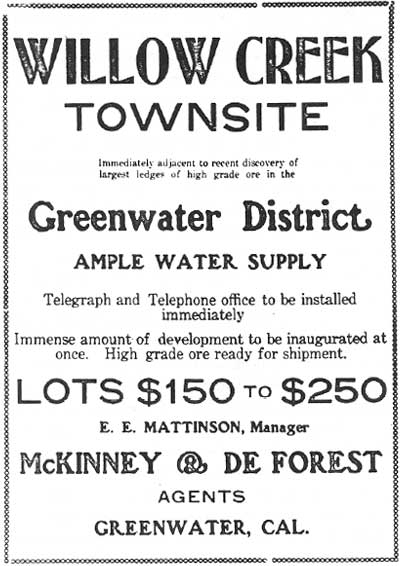

| Illustration 191. Advertisement for Ramsey's townsite, variously known as Greenwater, Ramsey and Copperfield. From the Bullfrog Miner, 31 August 1906. |

As August came to an end, the Greenwater District braced itself for the increasing rush which would undoubtedly come with the cooler weather of the fall and winter. Arthur Kunze and Harry Ramsey continued to promote their towns, and endeavored to attract the merchants which would make their camps the winner. Ramsey formed the Greenwater Townsite Company to promote his camp, and by the end of August he had a restaurant, two saloons, a hotel and a store. Kunze, meanwhile, had completed arrangements with several merchants, and the Greenwater Banking Corporation was organized, with a capitalization of $100,000, as well as the Greenwater Mercantile Company, which planned to erect a large general merchandise store. In addition, Kunze's site had a lodging house, a store, a saloon, a restaurant, and a number of tents as well as a "first class assay office.

Kunze seemed to have an advantage over Ramsey, since his townsite was higher in the hills, and was cooler than Ramseys site, which was on the floor of Greenwater Valley--an important consideration. The local folk, however, were divided in their assessment of the future winner of the townsite struggle, although the Rhyolite Herald picked Ramsey's camp to win. But whoever won, "the townsites are lining up for the struggle of supremacy and everything points to a prosperous fail and winter." [3]

As the fall season opened, the anticipated rush to the Greenwater District exceeded all expectations. The ingoing stages were crowded beyond capacity, and the congestion of freight and passengers at Johnnie Siding grew alarming. Huge piles of freight built up at the railhead, and many prospectors were reduced to walking the fifty-five miles to the camps. The competing townsites took advantage of the rush to proclaim their respective appeals. Ramsey's camp, despite being moved, still gave stiff competition to Arthur Kunze's town and Patsy Clark's camp of Furnace--although the latter was never intended to be more than a convenient camp for the miners working at Clark's Furnace Creek Copper Company mines. Dr. S. Trask of San Francisco was persuaded by Kunze to move into his town and start a drug store, a new saloon was started, and Bob Brogleman, proprietor of the Greenwater Mercantile Company, began construction of his large store. Several more boarding and lodging houses sprang up at Kunze's camp, until he could boast that ample boarding and lodging accommodations could be had. The Greenwater Banking Corporation started in business, and although the price of water declined slightly to 15¢ per gallon, water was still such a problem that the Ash Meadows Water Company was organized, at a capitalization of $3,000,000, in order to pump and pipe water in from that site to the growing towns of Greenwater.

By the middle of September, Jack Salsberry of the Tonopah Lumber Company reported that he had sold 150,000 board feet of lumber in Greenwater, and had orders backed up for 300,000 feet more. In addition, the lumber company had contracted to haul 625 tons of freight into the district, including 120 tons for the Kunze townsite and 16 tons alone for Brogleman's store. The lumber company by now had large water holding tanks erected at both Kunze's and Ramsey's townsites, and had several six-horse teams constantly hauling in water to supply the tanks.

Even though over 100 men were employed in the fourteen mines working in the district, labor was becoming scarce, as most men preferred to prospect on their own in the hopes of striking it rich, rather than settling down to a regular job. But as the boom continued, the camps seemed to show signs of being able to handle the influx of migrants. Although water still cost from $8 to $0 per barrel, "and the expense of feeding a mule is still as great as the money paid by a sojourner at a first-class hotel in New York City," there was at least enough tents so that most men who wished could sleep under cover, and it was possible to obtain food in the camps. In order to supply the increasing crowds, the Kimball Brothers increased their stage service from Johnnie Siding to a daily basis, and promised to try to make the trip to Greenwater in one day.

Al Neilson, the recorder of the Greenwater District, reported on September 21st that he had recorded 700 claims since the district was officially organized on September 6th. The Inyo Independent reported in mid-September that the district now had at least 1,000 people, with more crowding in every day. As could be expected in the midst of such a boom, trading in Greenwater stocks went wild. One company, the Independent reported, could fix its total value at $5 million based upon the selling price of its stock, even though it had sunk only to a depth of 280 feet, and had shipped no ore. The Associated Press, in turn, reported that during a two week period in September, sales aggregating a grand total of $4,125,000 had been made in Greenwater, and the "price of everything in the district has shot sky high." The Engineering & Mining Journal noted that Greenwater was "no place for a poor man, as provisions and water are both high in price, though on the other hand any prospect which may be found may be sold."

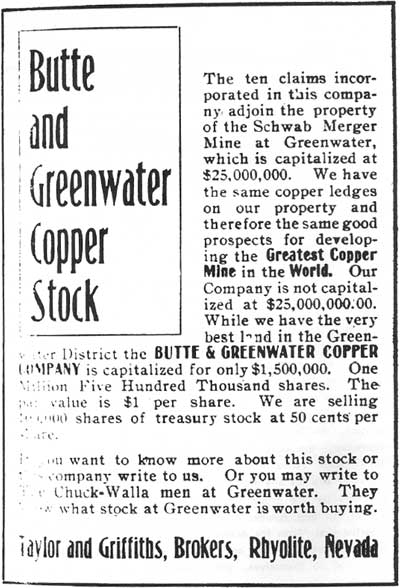

The Rhyolite brokerage firm of Taylor & Griffiths, who were gleefully trading Greenwater stocks as fast as they could get their hands on them, also reported the same trend. "The interest in the Greenwater district is intense. The demand for good properties is far in excess of the supply." As examples, Furnace Creek Copper stock, which had a par value of $1, and which was initially sold for 50¢ per share, was now trading around $4.50 per share, and Greenwater Death Valley was selling around $2. Furnace Creek Extension stock was put on the market at its par value of $1 per share, and was immediately oversubscribed, even though the company had not yet stuck a single pick into the ground. Greenwater, in short, was a promoters dream.

As September came to an end, it seemed sometimes that all of Rhyolite was decamping for the new district. Ramsey's town reported a population of 200, and at Kunze's, Bob Brogleman reported doing a land office business at his merchandise store, even though he hadn't finished building it yet. The Rhyolite papers began to blossom with large and elaborate advertisements placed by Greenwater companies, most of whom were not yet working. In September alone, six more mining companies were incorporated, bringing the total in the district to sixteen. The capitalization of thirteen of those companies totaled over $20 million. [4]

The month of October saw the height of Greenwater's boom, as everyone took advantage of the cooler fall weather to get into the district and locate good ground. During this month alone, fourteen more mining companies were incorporated in the district. As usual, some of these companies had mines, and some did not. With the great proliferation of mines and mining companies, moreover, the less honest of the mining promoters found it easy to cash in on the unbelievable boom spirit which surrounded the Greenwater name. Taking their cues from the two leading mines of the district, the Furnace Creek Copper Company and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, a confusing list of mining companies appeared on the local trading boards, as well as those in San Francisco and New York. Who, for example, could hope to remember the difference between the Furnace Creek Copper Company, the Greenwater Furnace Creek Copper Company, and the Furnace Creek Consolidated Copper Company, let alone the Greenwater Consolidated Copper Company, the Greenwater Copper Mining Company, the Greenwater United Copper Company, the United Greenwater Copper Company and the Greenwater Copper Company, each of which was a distinct organization?

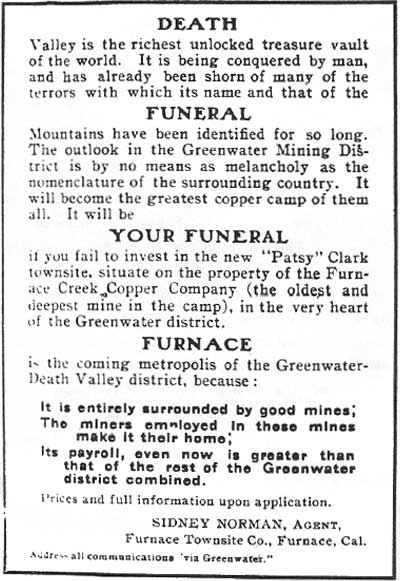

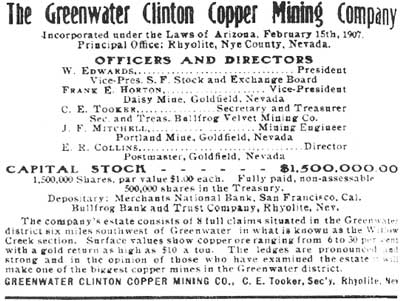

|

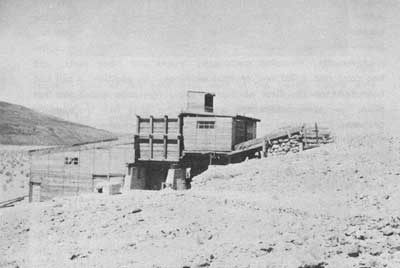

| Illustration 192. Ramsey, Greenwater District. Unfortunately, our only photo of Ramsey's townsite, alternatively known as Greenwater, Ramsey and Copperfield, is a rather poor one. This view was taken by representatives of the Engineering & Mining Journal during their trip to the area in October of 1906, and was printed in the Journal of December 15th. Photo courtesy of William Metscher collection, Central Nevada Historical Society. |

|

| Illustration 193. An early Greenwater mining advertisement, from the Rhyolite Herald, 19 October 1906. |

As with the mines, the towns of Greenwater also entered a true boom period. Construction began in early October on a two-story building for the Greenwater Banking Corporation, and a safe was ordered to store its money. By the middle of the month, the Inyo Independent reported that investment capital in the new district had already reached the $15 million mark. Every prominent copper operator in the United States had some interest in the district, and claims had been staked for twenty miles on every side of Greenwater. Over forty mining engineers had made reports on the mineral potential of the area for their respective employers, and it was the "unanimous opinion that Greenwater will excel in copper production, both the camps of Bisbee and Butte." [5]

The district by this time had 450 men and four women, and Kunze's town of Greenwater had five saloons, three restaurants, two general merchandise stores, and three lodging houses, where cots or springs on an old dry goods box cost $1 per night. Telegraph and telephone lines were being run from Bullfrog to Greenwater, and were nearing the town. Some luxuries were available, but when the first case of champagne entered the district, there were so many potential buyers that it was put up for action and sold for $150. Due to the lack of ice, liquor and water were both cooled by being stored in gunny sacks. The water itself served many purposes, first being used to wash dishes, second to wash clothes, and then given to the mules and burros to drink.

Happily, wages soared as high as prices, since miners who were willing to work steadily instead of prospecting on their own were somewhat rare. Unskilled miners and common laborers commanded $4.50 per day, carpenters were paid $8 daily and were in great demand due to the building boom, and expert miners received $5 to $5.50 per day. No one worked more than an eight-hour day. The boom is growing more tremendous with each day, summed up the Inyo Independent "Tons of machinery are being crowded into the Greenwater district; freight has become congested; every team for miles has been pressed into service and people are hurrying into the district as fast as the stage line can carry them."

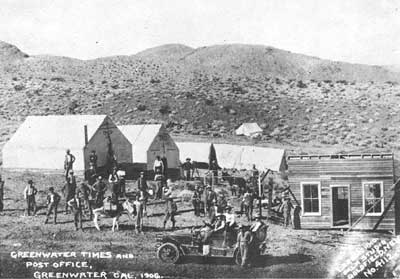

Between forty and fifty mule teams were hauling in supplies from Johnnie Siding, but no progress was made in reducing the back-load which was still piled high at the railhead. Kunze's camp of Greenwater was booming, and as much as $1500 was reported to have been paid for an inside lot. Kunze even succeeded in landing the pearl of every self-respecting mining camp, its own newspaper. On October 23d, the first issue of the Greenwater Times appeared on the streets. It was an eight page paper, published every Tuesday by James Brown and Frank Reber, and halt of its eight pages were canned material. Nevertheless, the rest of the issue was chock full of new, gossip and tidbits, some confusing and most exaggerated.

By this time the camp of Greenwater was beginning to change from a tent to a board town, and the Greenwater Times was sure to note all the newly constructed buildings. Bob Brogleman, proprietor of the Greenwater Mercantile Company, had a thirty by sixty toot frame building with a "handsome rustic front," which housed his store, hotel and restaurant. Messrs. Smith and Owsley had the newest saloon, in a twenty by thirty-foot frame building with a shingled roof, John Salsbury had an eighteen by thirty-foot office building almost completed, and his thirty by sixty-foot store building would be finished in a few days. Arthur Kunze's building was almost completed and it would house the Post Office, which had been granted to his townsite, as well as the bank and his private office. E. L. Phelps had his saloon in a boarded tent, Tom Murphy was building a men's furnishings store, and J. J. Griffith had let a contract for a twenty-room hotel. Commenting upon the building boom, the Greenwater Times smugly predicted that it was "safe to prognosticate that Greenwater will be growing thirty years hence." After all, the "future of the city of Greenwater is surely as open and easily read as any book--and the reading says it's the greatest copper city of a century."

The advertisements carried in this first issue of Greenwater's paper give an insight into other business establishments in the town. In addition to the ones mentioned above, the Greenwater Brokerage Company, the Greenwater Restaurant, Edward Behten's real estate, investments and mining office, the Do Drop Inn, the Greenwater Lumber Yard, the McKinney Glover law, mining, real estate and brokerage company, the Greenwater Club, Hunter & Hutner's civil, mining and electrical engineering firm, J. C. Davidson, notary public, Reber & Company's real estate and mining information offices, the Bank Saloon, and Kennedy & Lass's assaying and surveying service, all placed advertisements in the paper.

The booming mining business was also good for the labor interests, and by late October, the Greenwater Miners Union was over 00 strong. Meetings were held every Tuesday, and the Greenwater Townsite Company donated two "very fine lots to the union, where they intended to build their union hall. The miners started a fund drive to build and staff a union hospital, and proudly proclaimed its motto across the pages of the Greenwater Times "It is Justice the World Needs! Not Charity!"

In other news, the Times reported that the chief engineer for the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad was in town to select the best rail route into the district, and that due to public demand for living space, Patsy Clark had agreed to throw open his townsite of Furnace, which had hitherto been reserved for employees of his mine. Then, as was fitting, the first issue of the Greenwater Times closed with a large advertisement for the Greenwater Townsite Company. Greenwater was, according to this ad, "The Greatest Copper City of the Century." The payroll at its mines already exceeded that of Beatty, Bullfrog and Rhyolite combined, and $52,500 in real estate had been sold in Greenwater in the month of September. Still, however, business lots were available at "ground floor prices" to anyone interested.

Less than a week later, the Inyo Independent took its turn at marveling at the wonder of the eastern California desert. Lock at the place, the paper said, where back in July only one tent was to be seen. Now Greenwater was a well laid out city, with over 1,000 people in the district. At the present rate, the population would be 2,000 before the year was over The Bullfrog Miner, noting the same week that nearly $20,000,000 had been invested in 100 claims in the last six months at Greenwater, agreed that "by far the most sensational jump into prominence of any mining camp added to the map in many years is that of Greenwater . . . Greenwater is without doubt the greatest copper mining territory ever found in the world." Only the Engineering & Mining Journal, the far away and much more staid publication, managed to hold its breath. In a much more realistic appraisal, and one which immediately became immensely unpopular in Greenwater, the Journal noted that the "district is too new, however, to permit of trustworthy predictions as to its future, and it will take many months before development work can be carried far enough to establish its real value, and make it a factor in copper production. The present indications, however, are promising."

Although the Engineering & Mining Journal was absolutely correct in stating that it would be many months before anyone began making money by mining copper, that was too cold an assessment for a boom town. There were much easier and quicker methods of making money in a boom town, and although all of them were risky, there was not a lack of men who were wilting to try. Charles Crismor, for example, was a favorite Horatio Alger-type story much played up by the local papers. Arriving in Rhyolite in January of 1906 with 30¢ in his pocket, he had entered the restaurant business there. With the advent of the Greenwater boom, Crismor had grubstaked two prospectors with left-over food from his dining room, and by the 1st of November had sold the claims which they staked for a $150,000 profit. Such was the way money was made at Greenwater. The promoters who bought those prospects, in turn, incorporated a mining company to find cut if there was any ore in the ground, and sold stock shares to the investing public, which by now extended from the west to the east coast. The promoters paid themselves salaries out of the proceeds of the stock sales, and used the rest of the funds to look for ore. Only if ore was found would a profit flow back to the stockholders. H the meantime, as long as the boom lasted and people could be persuaded to invest their money in Greenwater's mines, everyone on the ground was making money.

As the boom continued and the mineral district spread farther and farther out across the desert, new towns appeared to accommodate those miners who lived too far from Greenwater, Copperfield or Furnace to walk to work. South Greenwater, for example, was started on the grounds of the Pittsburgh-Greenwater Copper Company, fifteen miles south of Greenwater itself, in early November, Later that month, the town of East Greenwater was started, to serve the mines in that area, approximately eight miles east. At about the same time, the first gas hoists began to arrive in the district, marking the transition of some of the companies from the exploration to the development stage of mining. Eleven more mining companies were incorporated in November, bringing the total in the district to forty-one. Many times that number of small mines, locations and prospects were also being held and worked by individual miners who were awaiting the proper price to sell their locations to mining companies.

And the towns continued to grow. Our best information concerns Kunze's Greenwater, since the Greenwater Times naturally boosted its own town over the rival camps. By November 6th, Greenwater had two barber shops, and twenty wooden buildings were in the course of construction. A lawyer had moved to town, to take advantage of the lucrative fees involved in the inevitable mining conflicts, Paul Wiesse had started a butcher shop, and two more restaurants were ready to open, bringing the total to five. T, E. Blake opened a shoe repair shop, two more offices full of mining engineers and surveyors opened, and J. C. Collins announced the grand opening of his Undertaker and Scientific Embalmer' services. So many carpenters were now in camp, serving the demands of the building boom, that they organized themselves as a local branch of the Nevada carpenters union.

Despite the boom fever, there were several firms besides the Engineering & Mining Journal which managed to resist the excitement of the rush. William Clark, president of the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad, for example, resisted the heavy local pressure to begin immediate construction of a branch line into Greenwater, and instead more reasonably announced that the branch road would be built "just as soon as we are fully assured of the camps' permanency." The pressure on Clark was tremendous, for if Greenwater did turn into a productive camp, the first railroad into the district would reap enormous profits. !n addition, the Greenwater fever had invaded the Clark family itself, for J. Ross Clark, William's brother, had invested in the district and incorporated the Clark Copper Company.

By the middle of November, the Greenwater phenomenon could no longer be called a boom or a rush in the usual meanings of those terms, and the Inyo Register described it best as a "stampede." No less than 100 people, said that paper, were arriving in the district every day, and still the demand for labor far exceeded the supply, since most of the newcomers preferred to look for their private bonanzas rather than settle down to shift work in the mines. As a partial remedy, mine superintendents had taken to placing pickets down the trails leading into town, in order to grab the miners as they arrived, and offer them jobs.

But the district still had several rather insurmountable problems, and in mid-November one of them was graphically highlighted when one of the water wagons serving the holdings tanks of the town broke down. An immediate panic ensued, and water prices shot up to $20 per barrel before the wagon could be repaired. It was a reminder, if any need be had, that Greenwater would never become a producing district until the water and transportation problems were solved, for under the present services only the very highest grades of copper ore could be profitably shipped out of the district.

|

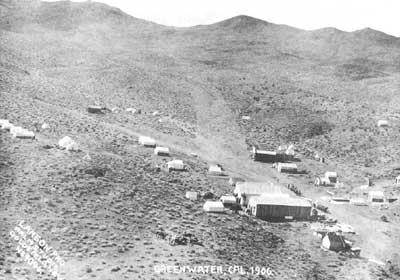

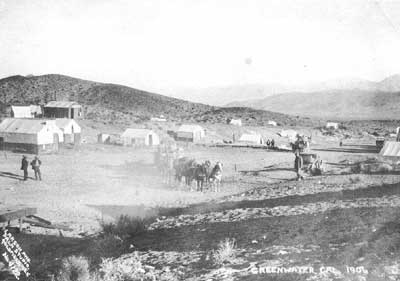

| Illustration 194. View of Kunze's Greenwater in late 1906, shortly before the townsite merger of Kunze and Ramsey's townsites. One large wooden building has been completed, and another is in the course of construction, while numerous tent and frame structures, the common mode of living, are much in evidence. Note the piles of lumber on the ground, the two freight teams in the middle of the street, and the feed yard in the center foreground. Photo courtesy Nevada Historical Society. |

|

| Illustrations 195-196-197. Several street scences in the bustling life of Kunze's Greenwater townsite. Unfortunately, shortly after these photos were taken, the townsite merger was announced, and most of the buildings were taken down and moved out into the flat to the site of New Greenwater. Photos courtesy Nevada Historical Society. Unfortunately, no photos survive of the combined town of New Greenwater, formed by the merger of Kunze's and Ramsey's camps. |

By the end of November, the Greenwater stampede was of such proportions that although the district had yet to ship a single sack of ore, it was getting almost weekly coverage by the national mining journals. California and Nevada prospectors, miners and capitalists are thronging into the new copper camp of Greenwater . . . . as fast as they can get there by automobile, stage, wagon, burro or afoot wrote the Engineering & Mining Journal "The trails across Death Valley and the Amargosa desert are filled with men on the way. Rich men, ready to buy anything with a likely look are plentiful, which is a sure proof that the camp is on the boom . . . . From a population of 75 at the end of October, the camp has grown to 1,000 in a few weeks, and not less than 100 men a day are arriving. Labor is in demand, and already about 500 miners have been set to work on the big properties, and as fast as experienced miners come in they are at once given employment." As one single example of the continuing boom, Thomas W. Lawson of Boston, a noted copper operator and millionaire, purchased the Greenwater Red Boy and Greenwater Saratoga Mining Companies in late November for a reported $2,000,000 in hard cash, and immediately announced plans to erect a copper smelter. Indicative of this boom spirit purchase is the fact that Lawson intimated that the smelter would be built at Greenwater, regardless of the fact that there was no where nearly enough water anywhere around Greenwater to support a smelting plant. One wonders how carefully Lawson considered his purchase before laying down his money.

By now the Greenwater boom was so great that the competition between the Kunze and Ramsey townsites became impractical. Kunze's site, due to its location nearer the larger mines, and its success in obtaining a Post Office, a newspaper and several leading business houses, was clearly leading in the townsite race over Ramsey's camp, but there were problems involved in Kunze's physical location. His camp was perched up in the Greenwater Hills, practically on the end line of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company mines, and only a wooden fence kept drunken miners from walking off the end of one of Kunze's streets into one of the mines' shafts.

In addition, the leading mine owners of the district realized that a railroad was an absolute necessity for the future prosperity of Greenwater, and building a railroad into Kunze's town would be difficult, due to its location in the hills overlooking Greenwater Valley. Nor were the railroad interests very anxious to build directly into the heart of the mining district, for they had painfully learned at Tonopah how expensive it was to lay tracks over active and conflicting mining claims. Thus the railroad companies, both for ease of construction and avoidance of involvement in expensive land battles, preferred to build their rail heads at spots away from the actual mines. Charles Schwab, in turn, was growing uneasy at the prospect of a large town night on top of his mining claims, since that would lead to difficulties in opening up new ground when the time came. For a combination of these reasons, the leading promoters of the district decided in late November to move Kunze's camp of Greenwater away from its present location and down into the Greenwater Valley below, where railroad construction and and acquisition would be much easier and less expensive. After all, the planners at this time were expecting Greenwater to blossom into a city of thousands, rivaling the other great copper towns of the United States, such as Butte, Montana, and there simply was not enough room at Kunze's site for such an expansion.

As a result, Harry Ramsey's camp of Copperfield, which had never enjoyed the prosperity of Kunze's, suddenly found itself saved. A new Greenwater Townsite company was incorporated, which bought out the interest of both Ramsey and Kunze in their old townsites, and backed by the capital of the leading mining promoters, announced that the entire Kunze townsite would be moved down into the valley, near Ramsey's old site. Owners of lots in both Kunze's and Ramsey's old townsite would be given lots of equal value and location in the new town, and the new combined townsite would carry the name of Greenwater.

After the announcement of the townsite consolidation, the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad reported that it would build a spur into the new site, and John Brock announced that he would soon start construction on a $60,000 hotel. All was not well, however, for with the coming of winter, although mild snowfalls helped alleviate the water shortage, the cold weather immediately pointed out another serious supply problem in the district. Wood was almost unavailable as a fuel to warm the tents and buildings of the district, and Greenwater residents began to experience a "lively skirmish to get enough greasewood to keep warm."

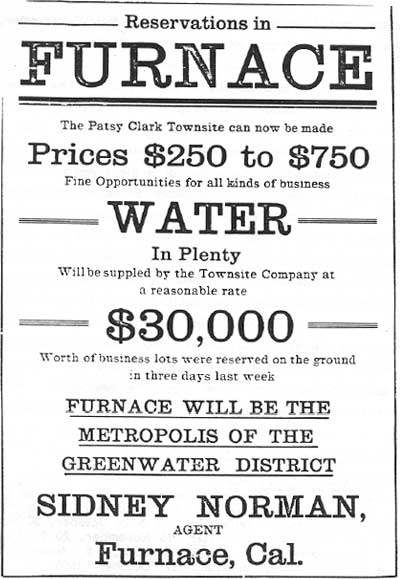

Then, just to keep the townsite situation from becoming too calm, Patsy Clark decided to promote his townsite of Furnace, and ads began running in the Rhyolite newspapers. Lots were on sale, according to the ads, for $250 to $750 apiece, and over $30,000 worth of lots had already been sold. FURNACE," the ad proclaimed, "WILL BE THE METROPOLIS OF THE GREENWATER DISTRICT."

But wherever they were located, and whatever they were called, all the towns of the district continued to expand. The Southern Nevada Telegraph and Telephone Company completed the extension of its telegraph lines into the district in mid-December, and promised that the telephone lines would soon be finished as well. Wells were being sunk by several hopeful individuals and water was struck in one, eighteen miles from town. The Greenwater Townsite Company began laying pipe from Greenwater Springs to the townsite, although the flow of that spring was nowhere near enough to accommodate the demand.

By the end of 1906, with the population of the district pushing 1,500, the boom was finally slowing down, although everyone blamed the unprecendented cold weather rather than any abatement of the Greenwater fever. Several snow storms in late December caused much suffering, and the price of greasewood, which became increasingly scarce, rose to $15 a wagon load. Twenty loads, it was reported, were necessary to equal the burning power of a normal cord of wood. The cold weather stopped work on most of the mines, for only those whose shafts were deep enough to escape the effects of the weather were able to continue work. Still, nine more mining companies were incorporated in the district in December, bringing the total to fifty, and everyone sat back, waiting for a break in the weather, so that Greenwater's unprecendented stampede could continue. During the lull in the the action, the townsite move began, and New Greenwater, "The Greatest Copper Camp on Earth," was born. [5]

|

| Illustration 198. The first advertisement for Clark's townsite of Furnace. From the Beatty Bullfrog Miner, 8 December 1906. |

Hard on the heels of the townsite consolidation came the news of another large merger, which set even the feverish minds of Greenwater agog. Several of the leading mine owners, realizing that the district needed a smelter in order to become a producer, announced the formation of a giant merger towards that purpose. On December 15th, Charles Schwab, John Brock, and some financiers from Philadelphia formed the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company. The merger company had a capital stock of 5,000,000 shares, par value $5 each, for a total capitalization of $25,000,000--an amazing sum which astounded even such boom-hardened towns as Goldfield and Tonopah. The new corporation was essentially a holding company, and consisted of the majority interests in the Greenwater Death Valley Copper company, the United Greenwater Copper company, and the unincorporated mines belonging to Brock and the Philadelphians. By pooling their resources, Schwab and his partners hoped to be able to cut costs and erect a large smelting plant for the reduction of the ores from each of the mines. Although no specific site was announced, Ash Meadows immediately became the leading contender for the smelter site, due to its proximity to a plentiful water supply and the railroads.

The new company announced that it would build its own branch railroad from the mines to the smelter area, thirty miles away, and that work would immediately begin on the railroad spur, the water development at the smelter site, and construction of the smelter itself. A smelting expert was hired by the merger company for $25,000 per year to supervise the selection of the plant site and construction of the smelter. In the meantime, although the mines involved in the merger came under the umbrella supervision of the new corporation, each would retain its separate identity and would continue to pursue its own development independently.

Spurred by this news, developments at Greenwater continued at a rather hectic pace. The townsite merger was being carried out, and in addition, Patsy Clark, who stayed outside of both the townsite and mining mergers, continued to plug his town of Furnace, By January 1st, that site was described as containing stores, business houses and a hotel. A separate stage line connected it with Amargosa, and a Post Office had been requested.

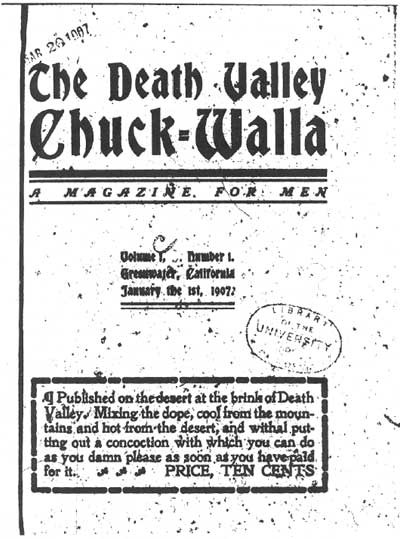

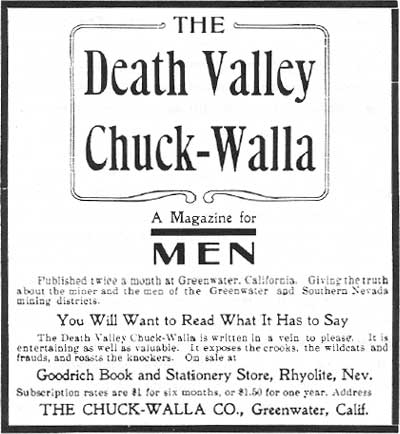

The new townsite of Greenwater was likewise experiencing growth, in addition to the confusion of consolidation. A second weekly newspaper, the Greenwater Miner, was started by an editor who was attracted to the boom district all the way from Nome, Alaska, and several more assaying, surveying and brokerage offices opened. But January saw yet another young publication start up, which turned out to be one of Greenwater's unique claims to fame, On January 1st, the first issue of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla hit the streets. The little magazine, published by C. E. Kunze and C. B. Glasscock, was best described by Glasscock in later years as "freakish." it was printed on butcher paper, for economy, and the two young editors launched their enterprise with a total capital stock of $35. As its advertisements read, it was "A Magazine for MEN." It was "written in a vein to please. It is entertaining as well as valuable. It exposes the crooks, the wildcats and the frauds, and roasts the knockers." And, as the cover declared, it was "Published on the desert at the brink of Death Valley. Mixing the dope, cool from the mountains, and hot from the desert, and withal putting out a concoction with which you can dc as you damn well please as soon as you have paid for it. PRICE, TEN CENTS."

The first issue of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla was especially unique, for it vividly described the total contusion inherent in the townsite move which was currently taking place. In an article, aptly titled "A Town on Wheels," the movement was portrayed: ". . . pandemonium reigns. Saloons and boarding houses, stores, and brokerage firms are doing business on the run and trying to be on both sides of the mountain at one time. A barkeep puts down his case of bottles on a knoll en route from the old camp to the new, and serves the passing throng laden with bedding and store fixtures . . . . The butcher kills a cow en route and deals out steaks and roasts to the hungry multitude hurrying back to the old camp to get the necessities for the new. Those who remain in the old camp are walking two miles to the new to get the eggs for breakfast. Those who have journeyed to the new are walking two miles to the old to get their mail, and a pair of socks. Through it all Jack Salsbury, Harry Ramsey and the Townsite Company smile . . . Questions as to the cause of the change are referred to the anti-publicity committee, and picturesque and forceful language as to the advisability of the change noted and filed for reference.

The Chuck-Walla had other aspects as well. Although the editors were totally committed to boosting the Greenwater District, they also realized that the proliferation of fraudulent mining schemes would hurt the district in the long run, and made it their pet project to uncover mining companies who were bilking the public. The first issue carried a long article damning the manipulations of the Boston-Greenwater Copper Company, promoted by J. Grant Lyman and his Union Securities company, Lyman, it may be remembered, had been arrested in Boston for pushing stock sales for non-existent mines around the Bullfrog area, and he was doing the same at Greenwater.

By January 4th, the Rhyolite Herald was able to report that the townsite consolidation was complete. Although the total population of the district and its towns was not easy to estimate, since so many men were constantly thronging through the hills, the Herald estimated it at between 1,500 and 2,000. More important, however, for the development of the mining district, was the report from the Fairbanks-Morse Company that it had received orders for at least twenty hoists of various sizes for the district, which indicated that more and more companies were beginning the transition from exploration to the development stage of mining. All the district needed in order to pass from a boom camp into a permanent mining town was for one big mine to make the next step, from development into production.

|

| Illustration 199. Front cover of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, printed on butcher paper (which makes it extremely difficult to reproduce), showing the actual size of the magazine. |

|

| Illustration 200. A typical advertisement for the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, this one appeared in the Rhyolite Herald on 8 February 1907. |

New Greenwater, meanwhile, reported thriving business. The townsite company surveyed 2,200 lots in over 130 blocks at the new site, and reported brisk sales. Lots on main Street sold from $500 to $5,000 apiece, and the county supervisors of Inyo county approved the townsite plat. The continuing cold weather, however, put a damper on business, as one miner reported that it was "fiercely damnable, and we put two-thirds of the time trying to rustle greasewood enough to keep from freezing." Despite the snowfall, water was still in short supply and was selling for $10 per barrel.

Nor were freight difficulties made any easier by the weather. The trip from Johnnie Siding by a loaded freight wagon took three to four days, and freight costs were still extremely high, due to the lack of enough teams to supply the demand. Freight charges from Johnnie Siding to Greenwater were $60 per ton, which succeeded in driving subsistence costs at Greenwater through the roof. The Greenwater Bank, however, reported no lack of business due to high costs, and in one week early in January reported $20,000 worth of transactions. Visitors to the district at this time could watch four separate surveying parties on the ground at the new townsite, as both the Las Vegas & Tonopah and the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroads had survey crews considering lines into the town, and the Southern Nevada Telegraph and Telephone Company also had two crews out, surveying lines for the telegraph and telephone extensions into New Greenwater, Farther up the road, a fifth survey crew could be seen laying out a new access road into Furnace. All in all, as the Engineering & Mining Journal noted, "There seems to be no diminution of the rush to the Greenwater . . ." The Journal however, was still puzzled about the Greenwater madness, for as it noted, "as yet none of the camps in that region has become productive."

The Engineering & Mining Journal was not the only publication to wonder at the immense rush into Greenwater. The Mining World, in late January, noted that "It is too early to predict the possibilities of this district. Its remoteness from transportation facilities and water have retarded its development, but notwithstanding the many difficulties encountered, very active work is being prosecuted on about 50 different properties. During the next six months, exploratory work will have probably progressed sufficiently to determine the persistence of the ore deposits. That was the crux: why was so much money being poured into the district, when the very existence of the ore deposits below the surface level had not yet been proven? Apparently the boom spirit, which had been ravaging throughout Nevada and eastern California since the bonanza discoveries at Tonopah and Goldfield, reached its height at Greenwater. In addition, since copper deposits at other camps such as Bisbee and Butte had always improved with depth, everyone assumed that the same would hold true for Greenwater. Since the surface richness at Greenwater far surpassed that of any copper camp ever, who could fail to think that Greenwater could indeed become the Greatest Copper Camp on Earth?

One paper, at least, did think exactly that. In late January the Goldfield Gossip printed its own assessment of the Greenwater District, and it was one which flew directly in the face of all the local predictions. "We have dissected reports from as many sources as possible regarding the future of Greenwater," wrote the Gossip "and all these agree that the camp would never make a production of copper to amount to anything." As might be expected, that report caused an immediate and extreme reaction from the Greenwater papers, particularly the Death Valley Chuck-Walla which more than adequately fulfilled its promise to "roast the knockers." The Bullfrog Miner also scorned the Goldfield Gossip's assessment, and printed its own: ". . . there can be but one future for Greenwater and that will be expressed by the six words 'Greatest Copper Camp in the World."

In the end, however, no one would know for sure whether Greenwater would turn into a producer or not until the actual time arrived, and meanwhile the Greenwater District enjoyed its booming prosperity. In late January, the Greenwater Times and the Greenwater Miner reported that the district had enjoyed its first marriage celebration. The growing affluence of the desert camp was also indicated by the notice of a piano for sale, and the Death Valley Auto Company was established, In addition, a town government committee was organized to supervise sanitary and police measures, and Inyo County appointed a Justice of the Peace and a constable for the district. District Recorder Nelson informed the papers that 3,000 location notices had been made in his book during the last five months, and estimated that probably 1,500 more had been recorded directly into the Inyo County books at Independence.

|

| Illustration 201. A typical Greenwater mining advertisement, as it appeared in the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, 15 February 1907. |

By mid-February, the Rhyolite Herald reported that it was confident that the Tonopah & Tidewater would build a branch into the Greenwater District, and even speculated that the road would be finished by June 1st. The Death Valley Chuck-Walla in its mid-February issue, put the population of the district at 2,000, including 500 in the town of Furnace, which was beginning to emerge as a real rival to the new Greenwater townsite. By this time, seventeen more mining companies had been incorporated since the first of the year, bringing the total of incorporated mining companies in the district to sixty-seven, but not all of them were working. Indeed, some of them never worked at all, as they were designed more to mine the pockets of gullible investors than to mine the ground. The Death Valley Chuck-Walla in one of its more valuable contributions, listed the mines of the area, and indicated that twenty-three of them were actually mining for copper.

Many of the mines listed by the Death Valley Chuck-Walla were not working, although most were planning to, and the magazine went on to specifically denounce several which it had proven were frauds. Neither the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mining Company, for example, nor the Greenwater Consolidated Mining Company appeared to own any ground in the district, although both were actively advertising and selling stock. The Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mining Company in particular seemed to be relying on the close similarity between its name and that of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company to bilk unwary investors of their money, for the latter was one of Greenwater's biggest active concerns.

|

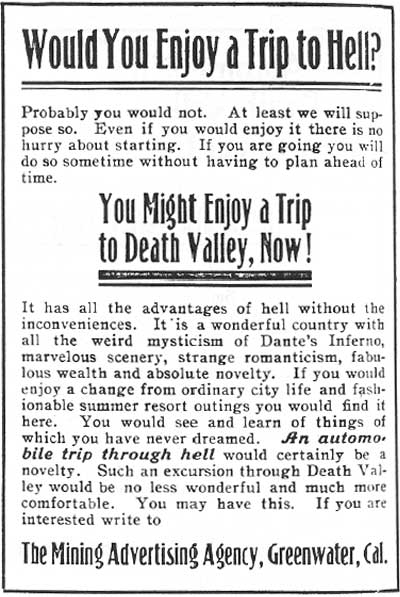

| Illustration 202. An advertisement for the combined town of new Greenwater, as it appeared in the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, 15 February 1907. |

The same issue of the Chuck-Walla carried a large ad for the Greenwater Townsite Company, which optimistically forecast that Greenwater would soon be the center of three railroads. The district's population, according to the ad, was over 2,000, and two telephone and telegraph lines were doing business. "Since the first of December lots have doubled in value. This is due to the fact that there is no question whatever about the permanency and future of the place. Greenwater is destined to be the richest mineral producing city on the whole globe." In addition, the magazine carried ads for several new Greenwater businesses, including the Greenwater Drug Company, and Alkali Bill's Death Valley Chug Line, a fanciful name for a desert character and his one automobile, who claimed he could take anyone anywhere for the proper price. Greenwater was now becoming so full of its own future, that the Engineering & Mining Journal reported that "From the desert comes the news that the Greenwater people believe that they are growing so rapidly that they need a county all to themselves, with Greenwater as the county seat."

But as February drew to a close, there was a decided slackening in the great Greenwater boom. The district had now been opened for well over a year, and had been in a boom stage for more than half that time, and as of yet, none of the companies which were sinking their shafts had found any ore under the surface which could compare with the rich surface streaks that had started the boom. This fact, while slow to dawn upon the district itself, was beginning to become apparent in the nation-wide stock market. The Rhyolite brokerage firm of Taylor & Griffiths also noted the trend, and commented in late February that the demand for Greenwater securities of acknowledged merit . . . has not been what it should be," but went on in the same breath to push stock sales. From a development standpoint, this district is making a most excellent showing . . . . The surface showing in the Greenwater district has never been surpassed in the history of copper mining . . . . It is now time for the man who is inclined toward copper to get in and secure same of this stock while it is low.

The Bullfrog Miner also noted the same slight slackening of the Greenwater boom, and reported that while "there is somewhat of a dullness pervading the camp, as far as the influx of people and industries is concerned, the properties are looking mighty fine. In a way, Greenwater was starting to succumb to its own over-blown boom publicity, for after the stampede to the district began to subside, everything else looked less than normal by comparison. [6]

But at the time, no one could possibly have hoped to persuade a Greenwater citizen that the bloom was beginning to fade. On March 1st, the papers reported that the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company was beginning to work on the smelter site at Ash Meadows. More immediate encouragement came from the news that Mr. Lemle was opening a sub-agency for Budweiser at Greenwater, and was arranging for daily ice delivery via auto. "If he can run his autos over the hot roads fast enough to keep the ice from melting en route," said the Death Valley Chuck-Walla "he will surely catch the trade." During the same week, the Greenwater Meat Company was organized, and advertised that it would drive cattle across two mountain ranges from Owens Valley, California, to Greenwater, in order to furnish a constant supply of fresh meat daily to Greenwater inhabitants. The Furnace Townsite Company also stepped up its advertisements, and the Greenwater Townsite Company countered by running its own ads, plugging the unique and desirable aspects of its camp. In its bi-weekly rundown on Greenwater mining, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla was able to list twenty-one mines and mining companies who were actively working in the district.

Still, qualms of uneasiness were beginning to be felt around the district. The Bullfrog Miner was the first local paper to admit such, noting that "As yet there are no real mines in Greenwater, as mining men understand the term." The paper went on to qualify that statement, adding that the working shafts are down several hundred feet and the ore bodies are well enough defined so that the owners know that they have immense quantities of very valuable rock, but the workings so far have been confined to these shafts and no effort has yet been made to take out ore except such as was necessary in sinking the shafts." Privately, many Bullfrog operators were glad to see that the Greenwater boom was abating, for at the height of the rush, the drain of investment money towards Greenwater had decidedly hampered the operation of the mines around the Bullfrog District.

The mid-March issue of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla noted little change in the district, with nineteen companies actively working. On the brighter side, the Inyo Register reported on March 15th that articles had been filed at Jersey City, New Jersey, to incorporate the Tonopah & Greenwater Railroad Company, with the purpose of building a railroad from the Amargosa Borax works to the Greenwater District. A capital stock of $500,000 had been created, and the construction of such a road, which would easily tie into the Tonopah & Tidewater, would mean a ready outlet for Greenwater's ores. Although no announcements were made, the Inyo Independent speculated that the recent incorporation undoubtedly meant that the Tonopah & Tidewater itself had decided not to build into Greenwater. The new railroad company was expected to start work soon, and complete the line by July 1st. Two routes had already been surveyed into the district, but no decision had been made as to which one to use.

|

| Illustration 203. A later advertisement for Patsy Clark's townsite of Furnace. From the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, 1 March 1907. |

By the end of March, the Bullfrog Miner put the population of the district at 2,000, which indicated that for the first month since the district had been discovered, it had not grown. Both Greenwater and Furnace, however, were described as being very alive and bustling, and both townsites had hotels, lodging houses, saloons, feed corrals, freight companies, meat markets, auto lines, brokerage houses, attorneys, newspapers, boarding houses, etc. In addition, three railroad lines had been surveyed into the district, the Ash Meadows water company was working on getting water piped into the district, and an electric light system was projected for the towns.

But the boom had definitely slowed, as evidenced by the incorporation of only seven more companies in the district in March. The following months of April and May would see one additional company incorporated during each, bringing the total of incorporated mining companies in the Greenwater district to seventy-three. Although that was more than enough, the cessation of incorporations meant that the exploration stage of the Greenwater district had finally drawn to a close, after a short but extremely violent boom, and the future of the district now depended upon what ore bodies were found under the ground during the subsequent development phase.

On April 1st, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla reported that twenty-four companies were presently engaged in finding out exactly what did lie under the surface of the ground. The pipe line for the Ash Meadows water system had been ordered, and a telephone connection had been completed between Greenwater and Furnace, enabling conversation between the two rival towns. Plans had also been announced for a new $50,000 hotel.

|

| Illustration 204. One of the most delightful advertisements of the Mining Advertising Agency, run by the editors of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, which epitomizes their distinctive style, 1 April 1907. |

|

| Illustration 205. Advertisement for Alkali Bill's famous auto line, from the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, 1 April 1907. |

Two weeks later, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla was able to report twenty-six companies working, but as of yet no one had found sufficient ore bodies beneath the surface of the earth to warrant full-scale production mining. Towards the end of April, the Bullfrog Miner reported that 300 men were working in the district, with about half being employed in the mines around Greenwater and the other half around Furnace. The payroll for the district was approaching $50,000 per month. The townsites had settled down from the boom period, and Greenwater was described as being mainly a rag town, although it had some wooden and one iron building. Lumber was still very expensive, costing $130 per thousand board feet, which depressed the building industry, but the bank was thriving, and business in general was good. Water still sold for the very high price of $7.50, as compared to $5 per barrel which had been the highest price Bullfrog had known in its early boom days.

By the first of May, although twenty-six companies were still actively engaging in development work, it was becoming very apparent that unless someone found a large profitable copper lode soon, the district would be in trouble. The investing public, which by now expected great things from the district which had boomed so brilliantly, was becoming impatient, and as another month passed without any big ore strikes being made, stock prices began to slip.

The Death Valley Chuck-Walla noted the stock slump, but blamed it on the eastern Wall Street stock manipulators "who wish to bear the stocks until they can be purchased at a rate far below their real value and therefore at great profit." In reality, the Greenwater boom had led to too great of expectations from the investing public, and suspicions of a gigantic fraud were now beginning to form among the ranks of far-off investors. Nor did it help the Greenwater District that the first effects of the Panic of 1907 were beginning to be felt on the eastern stock markets. Naturally, shares of mining companies which were still in the initial stages of development were among the first to be unloaded by cash-hungry investors. Still, no one was ready to give up, least of all the naive young men publishing the Death Valley Chuck-Walla They could write with pride that their magazine was read by more than nine thousand stock brokers across the nation, although they sadly noted that only 1,000 of them had paid for their subscriptions. [7]

On May 1st, the Ash Meadows Water Company ordered 135 miles of pipe for its various lines into Greenwater, Lee and other spots. The line to Greenwater, it announced, should be completed by the middle of August, when water would be available for around $4 per barrel. During the same week, Inyo County belatedly got around to implementing a full civil government for the district, appointing a deputy sheriff, a deputy district attorney, a deputy assessor, a deputy tax collector and a new Justice of the Peace. By the middle of the month, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla could report 300 miners still at work. One company had no less than six gas hoists going full blast, and several were down to the 300 and 400-foot levels. Unfortunately, no ore bodies had yet been found.

|

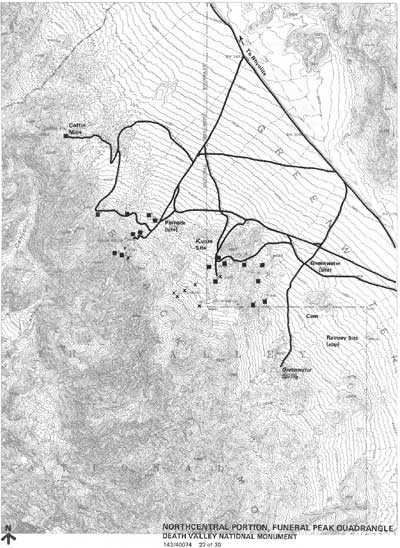

| Illustration 206. Map of mining district in immediate vicinity of Greenwater, Inyo County, California. California State Mining Bureau, Bulletin #50, September 1908. Map data compiled in May 1907. |

Towards the end of May, the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad announced the opening of Zabriskie Station, which cut the distance between Greenwater and the railroad considerably. The company also announced the establishment of an auto service between the station and Greenwater, with connections to both daily trains. The auto ride would take two and a half hours, and tickets were available from the commercial agent permanently stationed in Greenwater. The Inyo County commissioners also announced plans to consider the erection of a turnpike from independence to Greenwater, at an estimated cost of $1,000, whereby travel time between the two towns would be shortened by several days.

On June 1st, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla could still point to twenty-five companies at work, and although no sizeable ore bodies had yet been found, no one seemed quite willing to give up. Articles from the district's two other papers, the Greenwater Times and the Greenwater Miner, also contained the same hopeful spirit, and the Engineering & Mining Journal noted that fifteen gas hoists were at work throughout the district, and that more miners were at work than ever before. For once, the labor problem seemed to be solved, for the buying and selling of claims had ceased with the coming of harder times, and more and more miners were willing to give up their dreams of instant wealth and settle down to earning a steady wage. In late June, the Inyo County Board of Supervisors let out bids to construct a branch jail at Greenwater, and announced that the proposed sixteen by twenty-foot stone and cement building would contain three cells.