|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION IV:

INVENTORY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES--THE EAST SIDE

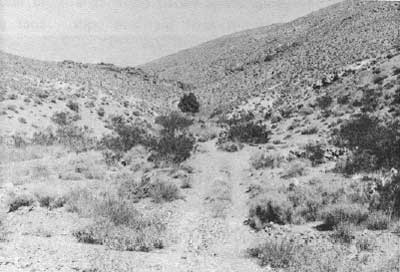

B. The Funeral Range

1. Introduction

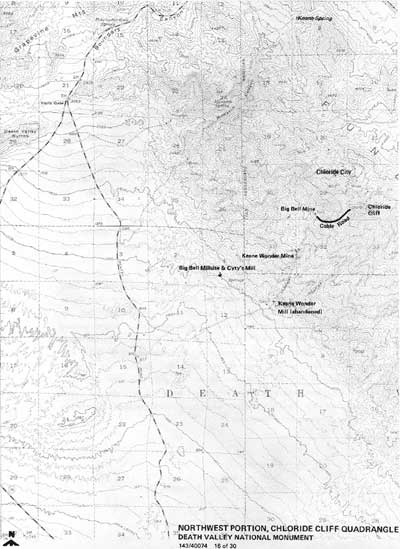

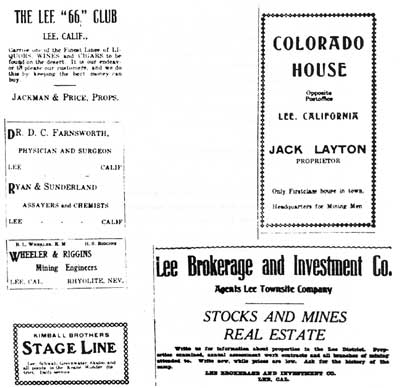

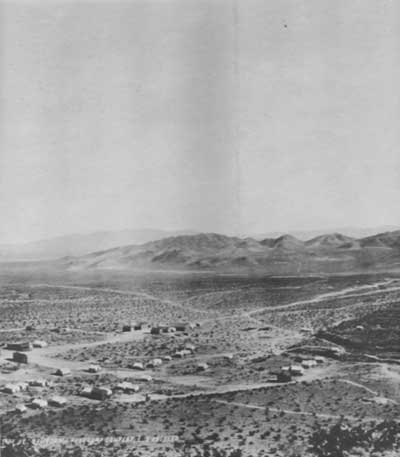

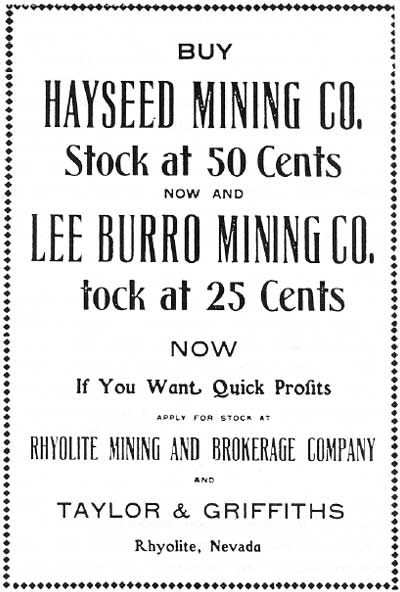

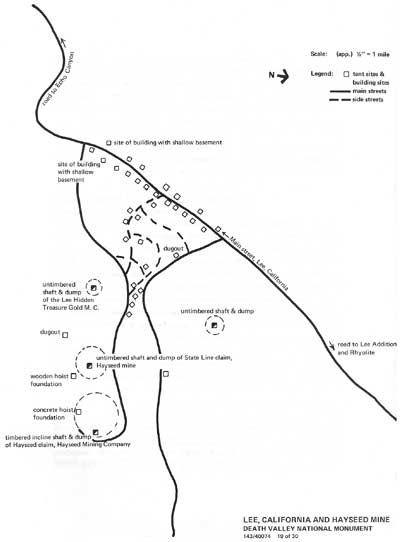

The canyons and hillsides of the Funeral Range, running down the east side of Death Valley, have seen a wide and varied mining history. One of the first mines in the Death Valley region, the Chloride Cliff, was discovered and worked here in the early 1870's, and one of Death Valley's most productive mines, the Keane Wonder, is also located in this area. But the real burst of activity within this region, lie so many others within Death Valley National Monument, was a result of the great Bullfrog boom.

In a sense, the Funeral Range and the Bullfrog Hills areas had a symbionic relationship. Although we cannot be sure, it is a good possibility that one of the reasons that the locators of the Keane Wonder mine chose the Funeral range to prospect in was their knowledge of the Chloride Cliff mine, which had operated briefly some thirty years before. Although the original Chloride Cliff mine was never really successful, that was due more to the difficulties and costs of transportation in the nineteenth century than to the lack of ore content at the mine, and the knowledge that there definitely was ore in the area probably drew the attention of early twentieth-century prospectors. We do know that once the Keane Wonder Mine was located, its early fame drew other prospectors to the region, two of whom went on to discover the Original Bullfrog Mine, which kicked off one of Southern Nevada's most spectacular mining booms.

The great success of the Bullfrog boom, in turn, stimulated a secondary rush to the Funeral Range, as prospectors fanned out over the adjacent territory on the theory that one good discovery would lead to another. In fact, as the Mining World wrote in January of 1906, when the rush to the Funeral range was well under way, "Death Valley is the best prospected section in the world. For many years the danger accompanying the investigation has lured men to prospect this ground, hoping that the danger had kept other men away."

|

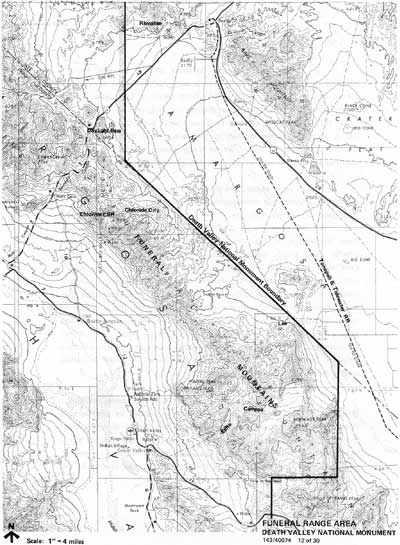

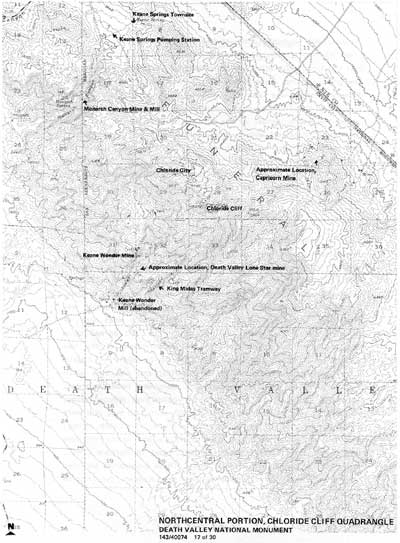

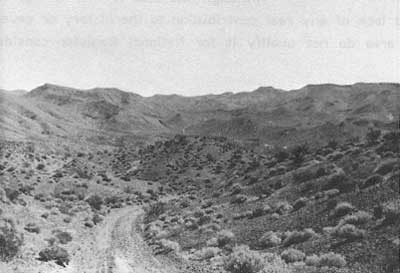

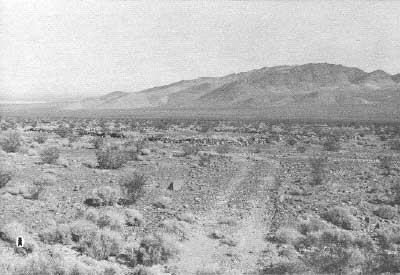

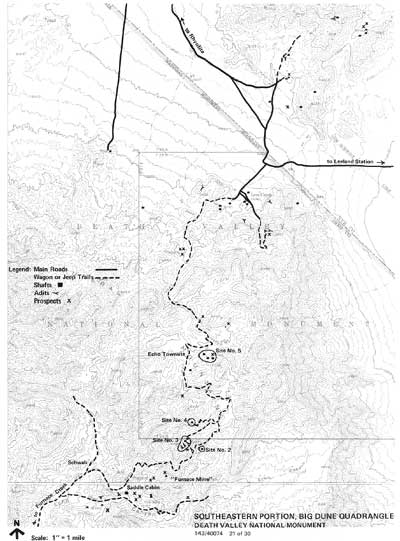

| Illustration 77. Map of Funeral Range Area. |

Although there is no doubt that the Funeral Range was covered with a swarm of prospectors during this time, their expertise was an arguable point. Another publication, the Mining & Scientific Press later called for a more thorough investigation of the possibilities of Death Valley, on the theory that the first mad rush to the region had been made by prospectors of questionable skills. "On the side favoring further prospecting around Death Valley it should be said that the prospectors have previously been the laziest lode-hunters on the desert. Much of the alledged prospecting has been done by "desert-rats," those half-mad desert tramps who never made more than a pretense of looking for ore. Their search was generally confined to trails between water-holes." The writer had a point, for many of the prospectors of the western mining frontier were no better than out-door bums, who followed the booms from one camp to another in order to cash in on the free-spending days of boom fevers. They were a representation of the losers of society, who found it easier to wander the hills in a vague search for gold while living off someone else's grubstake, than to look for a steady job.

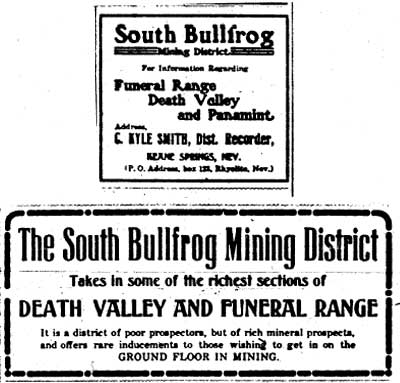

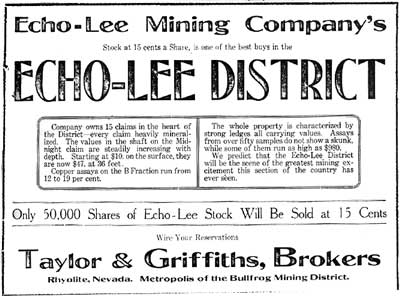

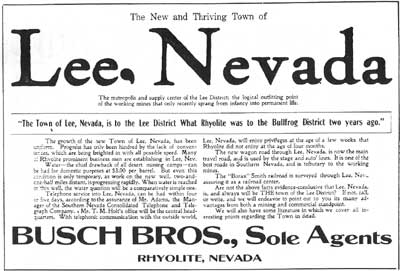

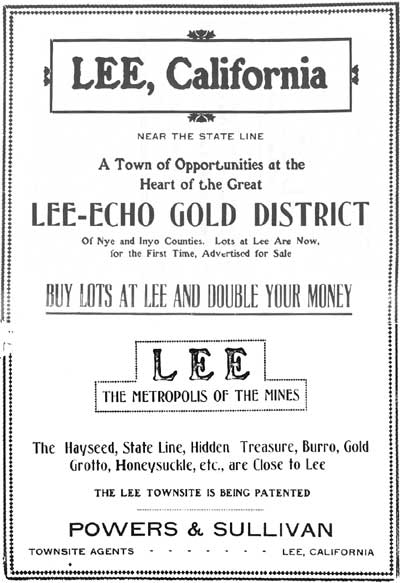

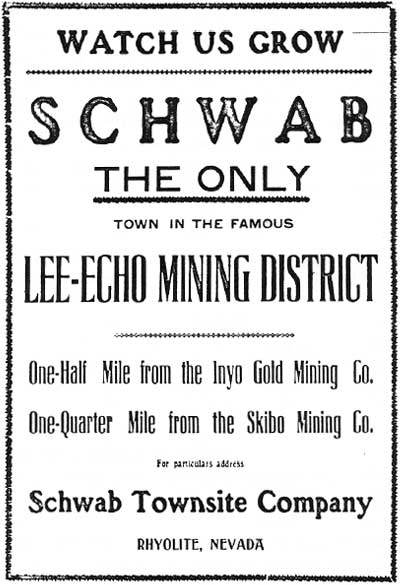

At any rate, whether experienced or not, dedicated or bums, the Funeral Range was thoroughly prospected in the years between 1905 and 1907, as the Bullfrog boom rose to its peak. Numerous mines and mining camps were established during that period, enough to cause the formation of two distinct mining districts subsidiary to the Bullfrog District. The South Bullfrog District was centered around the Keane Wonder and Chloride Cliff mines, in the northern half of the Funeral Range, and the Echo-Lee Mining District straddled the lower Funeral Range from Schwab on the west to Lee on the east. Between Daylight Pass on the north and Furnace Creek wash on the south, there was hardly a square mile of territory which did not contain a mine or prospect during this period. There was gold in the hills.

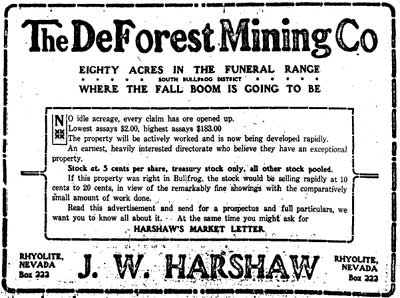

Unfortunately, there was not enough gold to support the number of miners who wanted some. The mines and prospects of the region were greatly exaggerated and over-publicized, due to the excesses of the boom fever. Every new location within these booming districts was hailed as the new Comstock lode, while similar discoveries in isolated regions which were not booming were totally ignored. Once that fever began to subside, however, the smaller mines were quick to fade away. Their demise was helped by two disasterous events which affected all of western mining: the San Francisco earthquake and fire in the spring of 1906 and the Panic of 1907. To a lesser extent the San Francisco disaster cut short the amount of investor funds which were available to the young mines of the two districts for exploration and development, but the real disaster was the Panic of 1907. It hit the booming districts just when the mining companies needed money the most, in order to build mills, improve roads, invest in machinery, and continue development.

These two events, coupled with the gradual demise of the Bullfrog District itself, foretold the eventual end of the South Bullfrog and the Echo-Lee districts. The smaller mines were the first to go, but they were soon followed by the larger ones, before any really had a decent chance to find out whether the ore in the ground was rich enough and extensive enough to make a real producing mine. The towns of the districts, such as Lee and Schwab, likewise died with their mines, and never were given the opportunity to develop into substantial mining camps.

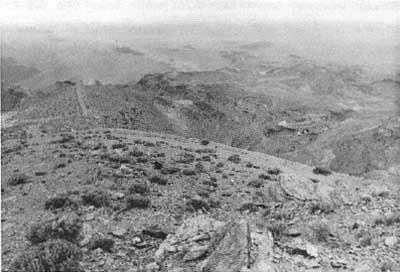

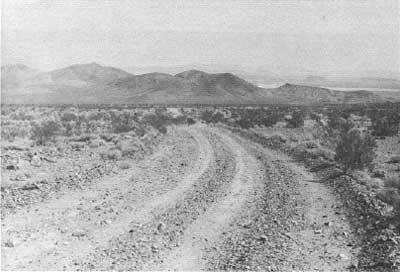

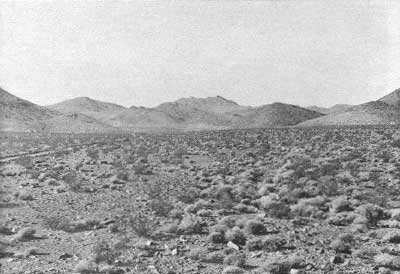

By 1910, the South Bullfrog and the Echo-Lee districts were almost deserted, with the notable exception of the Keane Wonder Mine, which steadily produced gold bullion throughout the years of discovery, boom and bust. But it, too, ran out of ore in the mid-1910s, and closed down. The Funeral Range was then left much as it had been found, except that uncounted shafts, tunnels, and prospect holes now dotted the countryside. Between 1920 and today, no significant mining has taken place within this region, although brief efforts were made to revive several of the larger mines. The scene today around most of these mines is much the same as it was seventy years ago. The only access to most of the region is along the old wagon roads and burro trails blazed by the Bullfrog era miners, and as years and washouts help the desert to slowly reclaim these roads, travel to the old mines and camps becomes more and more difficult.

But the South Bullfrog and the Echo-Lee districts were more typical than not of the life and death of mines and mining camps anywhere in the American west. For every famous mine and town, such as Goldfield and Tonopah, there were always hundreds of other mines and camps which tried and failed. The Funeral Range is, by and large, the history of such. [1]

2. Chloride Cliff

a. History

Chloride Cliff is a term which has been applied to a geographic area, a series of mines, a town, and a mining district. For the purposes of this discussion, Chloride Cliff will be used in its geographic sense, to define an area four miles square. This area starts at the Cliff itself on the south, where one may stand on an old mine dump and gaze down upon a spectacular view of Death Valley some 5,000 feet below, if the wind does not blow you off the side of the cliff. From here, the mining area stretches northwest beyond the site of Chloride City, with old mines and dumps covering the ridges and shallow valleys along the way.

The oldest mine on the east side of Death Valley National Monument, and one of the oldest within the entire Monument, is the original Chloride Cliff Mine. It was discovered on August 14th, 1871, by A. J. Franklin, a civil engineer employed by the U.S. Government to assist in surveying the Nevada-California state line. Although the story varies--some say he picked up a rock to kill a rattlesnake and found ore--Franklin somehow found what he thought was a vein of chloride of silver. He immediately staked out seven claims, called the Franklin Group, and the following October formed the Chloride Cliff Mining Company.

|

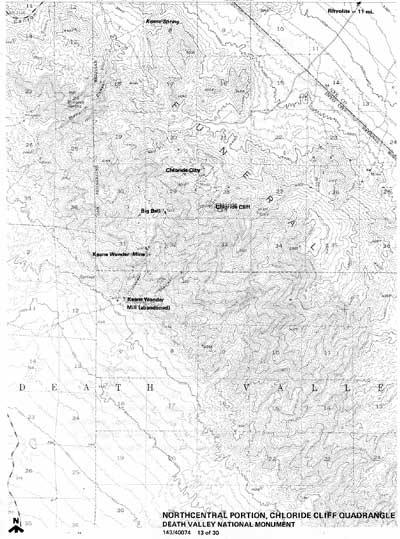

| Illustration 78. Map of North Central Portion of Chloride Cliff Area. |

In April of 1872, Franklin returned to his locations and began to work. Crude on-site tests indicated that his silver ore was worth between $200 and $1,000 per ton, and he began to dig a shaft. By July of 1873, when Franklin was employing seven miners, the shaft had been sunk to seventy feet, and he had nearly 100 tons of ore on the dump, ready for shipment. Transportation, however, was a definite problem, for there were as yet no distinct roads connecting Death Valley with any point of civilization. The mine was dependent upon San Bernardino, 180 miles away, for food and supplies, and although one man set a record for riding the distance in fifty-six hours, the normal string of pack mules took considerably longer to cover the route.

During 1872 and 1873, when the Chloride Cliff Mine was operating, pack trains arrived with supplies about every three months. As these mule teams traveled back and forth, they slowly identified the best route between Death Valley and San Bernardino, and by 1873, Franklin was proudly able to boast that a fully laden wagon could travel to within three hundred feet of his mine. This early route into the heart of Death Valley was subsequently used during the first years of borax mining at the Harmony and Eagle borax works.

But even with a new road to follow, the great expenses of packing in supplies and hauling out ore made the Chloride Cliff Mine unprofitable, unless a cheaper method of reducing the ore could be found. A newspaper reporter who visited the mine in 1873 summed up the situation facing Franklin. "in many things the prospects seem favorable, they have unquestionably struck a vast amount of ore but as yet the ledge is not sufficiently prospected to justify a great expenditure of capital in erecting works . . ." And while Franklin was trying to make up his mind, the great Panamint boom started on the west side of Death Valley, which made his small mine relatively unattractive to those who had capital to invest. After nearly two years of operation, the Chloride Cliff Mine shut down.

Given the poor records which have survived from these early days of mining, we have no estimate of production from the mine. The papers mentioned several times that pack mules were bringing out ore, but nothing more definite can be stated. But Franklin and his mine had a decided effect upon the future history of Death Valley. The wagon road blazed by his suppliers was used and improved by the large borax teams in later years, and Franklin had proved that there was ore in the Funeral Mountains. Thirty years later, when the Nevada mining boom began at Tonopah and Goldfield, prospectors remembered the old Chloride Cliff Mine, and came back to have another look at the area.

Franklin, in the meantime, did, not abandon his mine. Every year, he traveled back across the desert to perform the annual assessment work on the Chloride Cliff Mine, until his death in 1904. Then his son, George E. Franklin, followed in his footsteps, and kept the claim active via the required assessment work. Thus when the Bullfrog boom hit southwest Nevada, the younger Franklin held an active and valid claim, which could once more be profitable as transportation and supplies became cheaper through connections at the new boom town of Rhyolite. [2]

With the exception of the Franklins, the Chloride Cliff area was virtually deserted between 1873 and 1903, when the Keane Wonder Mine was located about two miles to the southwest of Chloride Cliff. Then, in 1904 the Original Bullfrog Mine was discovered, and the great Bullfrog boom was on. As the ground around the Bullfrog Hills was soon covered with locations, prospectors gradually spread farther afield and their attentions were naturally drawn rather quickly to the Chloride Cliff area. This region, after all, had already produced two mines, the Franklin Mine in 1873 and the Keane Wonder in 1903.

George Franklin was on the scene, and the new excitements caused by the Keane Wonder and the Bullfrog boom made him redouble his efforts on the old Chloride Cliff Mine. In the meantime, numerous other mining companies were appearing, as locations were made, bought and sold, and consolidated. The area around Chloride Cliff, from Daylight Springs in the north to Furnace Creek in the south, and from Death Valley on the west to the Amargosa Valley on the east, was swarming with prospectors, and in September of 1905 the South Bullfrog Mining District was formed. The old Chloride Cliff Mine, which was now commonly called the Franklin Mine, was included in the new district.

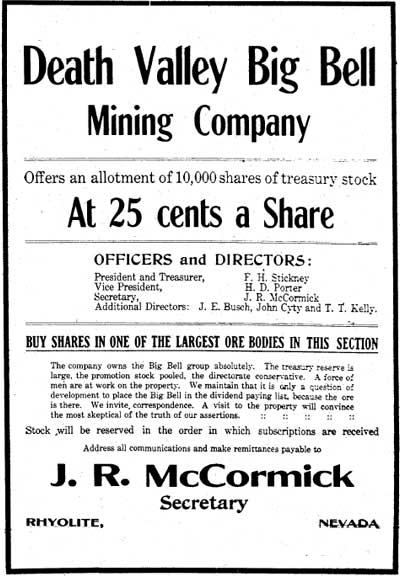

George Franklin soon had plenty of company. In the immediate vicinity of his mine, the Mucho Oro Mining Company began operations in April of 1905, the Bullfrog Cliff Mining Company was formed in October, and the Death Valley Mining and Milling Company appeared in November. These three companies, along with Franklin's mine, soon dominated the best ground in the Chloride Cliff area, and squeezed out the smaller companies and prospectors. By the end of 1905, the Mucho Oro had a tunnel in sixty feet and reported assays of $25 per ton. The Bullfrog Cliff Company, described as being "near" the Franklin Mine, was working ten miners, had a fifty-foot deep shaft, and reported ore values from $30 to $100. The Death Valley Mining and Milling Company, operating on ground next to the Bullfrog Cliff, reported five miners at work on two tunnels, with ore worth $40 to $60 a ton. George Franklin, still carrying on alone, reported average ore values in his old mine of $28.

|

| Illustration 79. Copy of an early stock certificate, date September of 1905. Courtesy Dr. Richard Lingenfelter. |

All this mining activity, naturally, called for a supporting townsite, or at the very least a small mining camp, and Chloride City was born in 1905. Located in a shallow and wide saddle 4,800 feet above Death Valley, the little town was placed in a very picturesque spot, for those who could stand the winds which constantly whipped across the Funeral Mountains and brought snow and blizzards during the winter months. Chloride Cliff is depicted on a 1905 map as being a few blocks square, and surrounded by mines and prospects. Water for the mines and miners was packed in from Keane Springs, three miles north, and wood for the barren Chloride Cliff region was brought in from ten miles away. Prospects were promising, however, and the Chloride Cliff area had all the indications of becoming another boom camp. [3]

During the first months of 1906, developments proceeded at the Chloride Cliff mines. The Bullfrog Cliff reported that it had enough ore in sight to support a small mill, and purchased water rights near Keane Springs. J. Irving Crowell, the mine's principal owner, went to San Francisco to conduct mill tests and arrange for financing. The Death Valley Mining and Milling Company continued to drive its two tunnels and reported in February that it had fifty tons of $50 ore on the dumps, and one hundred tons of lower grade. The company announced that it would send its ore to the new custom mill at Gold Center for processing, when that mill was completed. While awaiting that time, the mine shut down temporarily. The Franklin Mine also continued to work, reporting in March that its shaft was 150 feet deep, with average ore values of $17 per ton.

In April The Death Valley Company began mill tests upon its ore, to determine the best method of treatment, and let a contract to have its tunnel extended another 350 feet. Then, the San Francisco earthquake and fire occurred, and the Chloride Cliff mines cut back on operations, as everyone waited to see what effect the destruction of the West Coast's financial center would have upon the mines. Very little work was done through April and May, and in June the Death Valley Mining & Milling Company owned the only Chloride Cliff mine which was able to resume operations.

The San Francisco disaster seemed to be the last straw for George Franklin. In July he finally gave up and sold the mine which had been in his family since 1871 to a Pittsburgh syndicate for a reported $150,000. The new owners, however, made no immediate moves to reactivate the mine. The Death Valley Mining & Milling Company, however, forged ahead with its development plans and work, and began considering a mill of its own, since it was becoming evident that the Gold Center mill would never be completed. The company inserted large advertisements in the Rhyolite newspapers, pointing out to potential investors to opportunities presented by the promising mine. But the post-San Francisco climate was not conducive to investment in a small and unproven mine, the advertisements proved futile, and the Death Valley Company abruptly shut down operations in late July. All the Chloride Cliff mines were now idle. [4]

The mines of Chloride Cliff then went through a period of hiatus. During the last half of 1906, and all through 1907, 1908, and 1909, while the rest of the Bullfrog District and the South Bullfrog District were experiencing their biggest boom years, the Chloride Cliff mines lay idle. Despite the fact that the Keane Wonder Mine to the west was now producing gold month after month, and that the Chloride Cliff mines were surrounded by the boom and bust cycle taking place elsewhere in the South Bullfrog District, these mines saw no activity. The Death Valley Mining and Milling Company did announce plans to resume work in April of 1907, but it never did.

During this period, however, one thing did happen, for most of the Chloride Cliff mines were slowly consolidated into one large company. Exactly when this took place is unknown. The Franklin group was sold again in February of 1907, but the transactions involving the Bullfrog Cliff and the Mucho Oro mines are unrecorded. By December of 1907, though, the Chloride Cliff Mining Company had been formed, which included the properties of the Franklin Group, the Bullfrog Cliff and the Mucho Oro companies. J. Irving Crowell, the former president of the Bullfrog Cliff Mine, was the president of the new company. Crowell announced that work would be resumed on the combined property in December of 1907, but his promise went unfulfilled.

All during 1908 the only activity at the combined mines was the required assessment work, and the same was true in 1909. !n December of that year, however, Crowell was finally able to announce that work would be resumed shortly and this time his promise was met. The mines had been leased to the Pennsylvania Mining and Leasing Company, which intended to develop the properties of the Chloride Cliff Mining Company. The stockholders of the Pennsylvania company, said Crowell, were "disposed to put the property into producing condition," and had ample funds available for the task. [5]

Finally, in December of 1909, after an interval of over three years, serious work began on the property of the Chloride Cliff Mining Company. Development work began that month, and by the first week of 1910, the company was beginning to sack ore for shipment. The mine made a small twelve-ton shipment to a Rhyolite mill for testing purposes, and began to consider the construction of a mill at Chloride Cliff. The Rhyolite Herald proudly announced the resumption of work and described the holdings and prospects of the company in glowing terms. The Chloride Cliff Mining Company, it reported, had leased its entire holdings to the Pennsylvania Mining and Leasing Company. Prior developments on these properties, which included the claims of the former Franklin Group, the Mucho Oro Mine and the Bullfrog Cliff Mine, consisted of four tunnels ranging from forty feet to two hundred feet in length, and eight shafts from eighty to one hundred feet in depth. Prospects were extremely promising, said the Herald and the world would soon see a flow of gold from the long neglected mines of Chloride Cliff.

The ore tests carried out in Rhyolite were successful, with average values of $37 per ton obtained, and in late January of 1910 the Pennsylvania Company announced definite intentions to build a mill. During February the company began improving the road between its estate and Rhyolite, in order to facilitate the delivery of mill machinery. The Nevada-California Power Company, which was considering the extension of power lines to the Keane Wonder Mine, promised to extend another branch line to the Chloride Cliff mines when the Keane Wonder line was built. In late March the company's small mill arrived and was installed. It was only a one-stamp prospecting mill, with a ten to twelve ton daily capacity, but its purpose was to enable the company to conduct ore tests on the spot. The mine had a small supply of high grade ore, and hoped that by running it through the little mill, funds would be generated to build a larger one. The mill was installed on the side of the cliff below the old Franklin Mine, which was the main group of claims being worked.

By the end of April, the Rhyolite Herald was able to announce that the Chloride Cliff Mine was finally making good. The Pennsylvania Mining and Leasing Company had now expended $10,000 on improvements and developments on the property, and the new mill was installed. Hardly was it placed in operation, however, than the company found that the available water supply was too small to run the mill, and it was shortly abandoned. With its new mill useless, the company shifted gears and proposed to lease one of Rhyolite's idle mills, and to haul its ore into town for reduction there.

But developments came slowly. The company succeeded in leasing the Crystal Bullfrog Mill at Rhyolite, and obtained a 12-horse team to haul ore to the mill site, but as June stretched into July, no ore shipments were made. The company was employing eight miners at the mine, but developments proceeded at a rather slow pace. In the meantime, the Pennsylvania Mining and Leasing Company was undergoing internal reorganization, and in August J. Irving Crowell, president of the Chloride Cliff Mining Company, emerged as president of the Pennsylvania Company. Crowell was thus in charge of the company which was leasing ground from the mining company of which he was also president.

After the reorganization, activities quickened. One hundred tons of ore were treated at the Crystal Bullfrog Mill in August, and Crowell announced that the mine could keep the mill well supplied for quite some time. Average values of the ore taken to the mill were $35 per ton, and the mill reported savings of 90 percent of the value of the ore. Taking these figures, the mine should have received returns of $3,250 for the ore which was treated in August. With the initial successes, the company announced plans to increase its ore shipments in the near future, and searched for more horse teams to haul ore. The company still owned a good water right about three miles from the mine, but the cost of installing pipe and pumping water uphill to the mine would be high. Nevertheless, the company planned to do just that, provided that the ore values in the mine held up with development. Although sporadic work was being done on all the company's claims, the main mining effort was still being concentrated on the old Franklin Mine.

From August to October of 1910, the company continued to work. Ore output was increased, and the company soon had four sets of horse teams hauling ore from the mine to the mill. The dumps at the mine contained over 200 tons of milling ore, and seven tons were delivered to the mill each day. During September, the Pennsylvania Mining and Leasing Company also began to ship some high-grade ore directly to the smelters at Needles, California and Goldfield, Nevada. Then, in the middle of October, work stopped while more plans were made.

The company announced that it had decided to enlarge its own one-stamp mill at Chloride Cliff. Three hundred tons of ore had by now been processed at the Crystal Bullfrog Mill, but the average mill savings had only been 60 percent on the average $30 ore. The company was obviously losing much of its ore content, which it could not afford to do. The company planned to continue sending selected high-grade ores directly to the smelters, but would add two. more stamps to its own mill, as well as concentrating tables and cyanidation treatment. Water development was in progress at the company's source near Keane Springs, and the enlargement of the mill was of necessity dependent upon the delivery of water to the mill site. To do this, the Pennsylvania Company intended to install a four-mile pipe line and a pump at the springs. The costs would be high, but J. Irving Crowell stated that the ore uncoverings in the mine justified this kind of expenditure. The Rhyolite Herald supported Crowell's plans, for more development meant more work for local miners. Although only nine men were employed at the Franklin Mine, the company had hired as many as nineteen while ore shipments were being made, and the enlargement of the mill at Chloride Cliff would mean work for double that number of miners. [6]

As often happens, when a mine ceased work in order to develop future operations plans, it really meant that the company had no clear idea of what to d next. This was the case of the Chloride Cliff Mining Company and the Pennsylvania Mining and Leasing Company. Neither company had the resources to develop a small and isolated mine into a paying proposition, even if there was enough ore in the ground to warrant such expenditures. As a result, the Pennsylvania Company let its lease expire, and the mine lay idle as the Chloride Cliff Company searched for another source of capital. The solution was not found until April of 1911, when it was announced that the Chloride Cliff property was to be sold to an English corporation "of considerable financial strength."

J. Irving Crowell, who had been in London to negotiate the deal, told the Rhyolite Herald upon his return that a company was being formed in London to take over the property, and that a fund of several hundreds of thousands of dollars would be provided for a thorough prospecting and development of the twenty claims of the Chloride Cliff property. As soon as sufficient ore was uncovered, suitable machinery for reduction would be installed. This would likely involve the erection of an extensive wire tramway which would stretch from the mine to a new mill site, which would be located near the water source. In the meantime, the old Bonanza Hotel would be removed from Rhyolite and rebuilt on the Cliff property to house the miners.

The new company evidently meant business, for a representative of the Lechion Cable and Tramway Company of Denver, which had built the aerial tramway for the Keane Wonder Mine, arrived in mid-April to inspect that tramway and to propose plans for building another one for the Chloride Cliff Mine. But snags developed in the negotiations for the sale of the Chloride Cliff mines, and towards the end of May, the Rhyolite Herald was forced to announce that "negotiation for the ultimate purchase of the Chloride Cliff property is still in progress . . . ." The purchase was still expected to be completed, however, which would "result in activity on an extensive scale very soon."

For the next two months, negotiations lagged. Although the Herald reported that the second of three payments for the property had been made, final transactions were still stalled, and the paper speculated that the deal would be made in time for mining to start with the cooler weather of October. But during the following month of September, the sale was still not completed, although Crowell announced that the final payment of the $250,000 purchase price was expected soon, and that the new company intended to spend at least another $250,000 in developments and improvements on the property. But still the sale was not completed. Crowell made another trip to London in October, and reported on his return that everything was progressing well. The English syndicate in turn sent a mining engineer to inspect the property in November, and Crowell again announced that the deal was progressing satisfactorily.

By late December, the patient Herald was able to announce that the deal had finally been closed, and that the English managers were expected in town early in 1912, when work would be started. But in February the paper was still saying the same thing. By March of 1912 it became apparent that the sale had not been made, and that it never would be. Crowell worked the property himself for a short time, before announcing in June that "Permanent operations on this property are again placed in the future. . ." [7]

At this point our knowledge of the detailed activities at the Chloride Cliff become less perfect, as the Rhyolite Herald ceased publication. Still, even with the death of the Bullfrog District, Crowell hung on and worked the property by himself from time to time. In April of 1916 a small Lane mill was constructed on a group of claims just west of the abandoned site of Chloride City, but the mill operated only a few days, due to the shortage of water. A sixty-foot deep well which Crowell had dug about a mile from the new mill site went dry almost as soon as the mill was started. The mine and mill were listed as idle in 1917.

But Crowell still held on. Annual assessment work was done on the property through at least 1922, although Crowell was forced to sell a portion of his claims that year to satisfy some debts. In 1926 the mine was reported to be idle, and in 1928 it was sold to Louis McCrea of Beatty, who made several shipments of ore to a Salt Lake City smelter. The only recorded shipment during this time resulted in a profit of $47 per ton for thirty tons of ore. Between 1928 and 1931 several more shipments were made, but all were of small quantities, and in 1931 the property was being operated by the Chloride Cliff Mining & Milling Company, a new organization, which leased the mines from Louis McCrea. The new company, as usual, had grand plans to develop the mines and to pipe in water from twenty miles away, but as usual, nothing happened.

The mine, however, was still active in 1935, when six men were employed, who shipped 100 tons of ore in that year. At this time, all the mining work was being done on the surface, and it was reported, in an understatement, that the company needed "further equipment." In 1938, the California Journal of Mines and Geology reported that the mine, still owned by McCrea and his associates, had shipped about thirty tons per month between 1932 and 1936, before leasing the mine to the Coen Company who operated it from 1936 to 1937. After a few years of inactivity, McCrea was again reported to be shipping gold ore to a mill at Benton, California, in 1941.

During that same year, the Chloride Cliff area saw yet another mine make its appearance, when cinnabar was discovered a short distance northwest of the Chloride City site. The Crowell Mining and Milling Company undertook to develop this discovery, and erected a five-ton Cottrell mercury plant. But before more than an estimated 150 tons of ore could be processed, the small mercury plant caught fire and burned to the ground. The loss was too much for the company to absorb, and the cinnabar mine in turn was abandoned. This marked the last gasp of the Chloride Cliff area mines. Although intermittent prospecting and a few very small operations continued for several more years-forty-four claims were filed with the National Park Service between 1956 and 1960--no further significant activity took place. [8]

b. Present Status, Evaluation and Recommendations

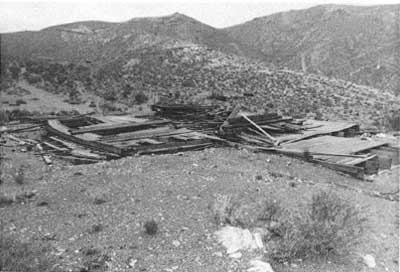

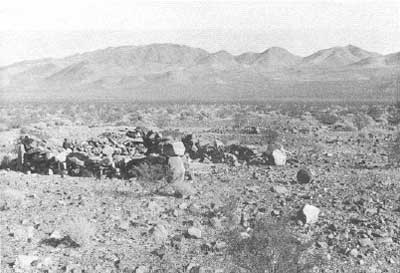

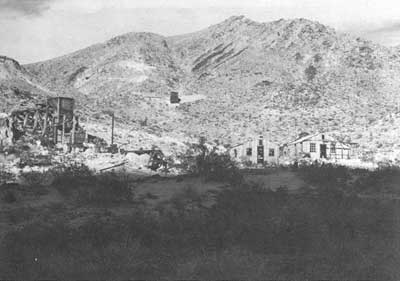

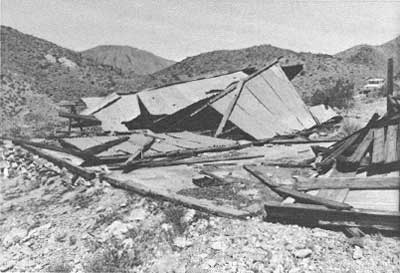

The entire Chloride Cliff area is cluttered with old shafts, adits and dumps, as well as collapsed buildings, dugouts, and several rather modern shacks. Some of these old mine sites indicate that activities were carried out over a period of several years, but most point to efforts lasting little more than several months. The mines were scattered over a four-mile square area, and significant remains may be found in five distinct groups.

At the southern end of the mining area, the site of the original Chloride Cliff Mine, or the Franklin Mine, can be positively identified. This mine group, which consists of four or five adits, with large stoped out areas in between, is situated on the very edge of a steep cliff (hence the original name), from which a spectacular view ranging from Badwater to Mt. Whitney may be seen. This is the, site of the original discovery of the Chloride Cliff Mine by A. J. Franklin in 1871. The mine was worked for two years by Franklin, and was then revived by his son and succeeding owners in 1905-6 and 1910. There are no structural remains at this site, and there is no way to identify which part of the mine was worked in the 1870s and which in the 1900s.

|

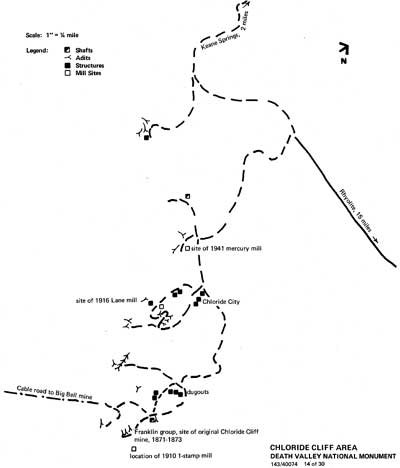

| Illustration 80. Map of Chloride Cliff Area. |

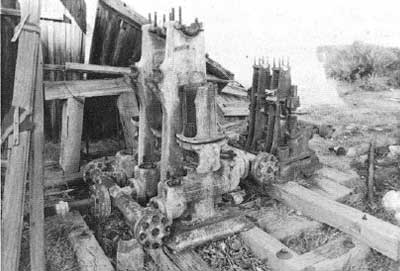

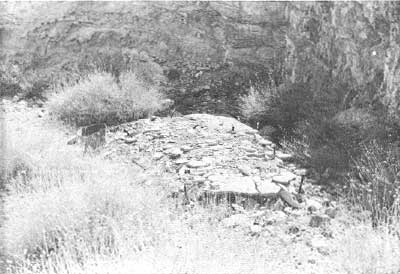

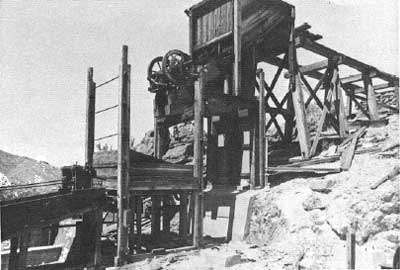

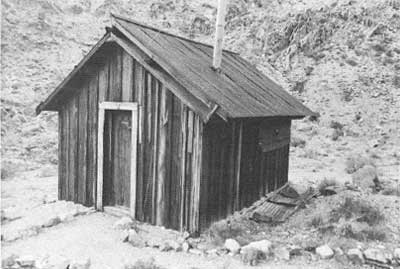

Part way down the cliff below this mine group stands the 1-stamp mill erected in 1910. There is very little evidence of a trail leading from the mine to the little mill, although a trail does descend from the mill site down into the ravine below. Remains of a primitive ore chute can be seen stretching from the mine about half way down to the mill site. The ore chute was obviously constructed of very cheap materials, and was used for a short time to slide ore from the mine down to the mill site. Several short exploration adits may also be seen along the trace of the ore chute. In addition, remnants of one inch pipe are scattered down the cliff side, tokens of the ill-fated effort to pipe water to the mill.

The 1-stamp mill itself is in excellent shape. Undoubtedly this is due to its inaccessibility, for anyone climbing the hill from the mill to the mine above would rue the addition of any extra weight. The mill machinery bears the markings of the Union Tool Company of Los Angeles, and the main support timbers stand twenty feet tall. The total lack of debris, waste rock or tailings around the mill indicate that it was briefly, if ever, used. When operations were abandoned at the mine above, only the engine and flybelt were salvaged. With a little oil, it looks as if the mill could run today, for virtually all its parts are intact.

|

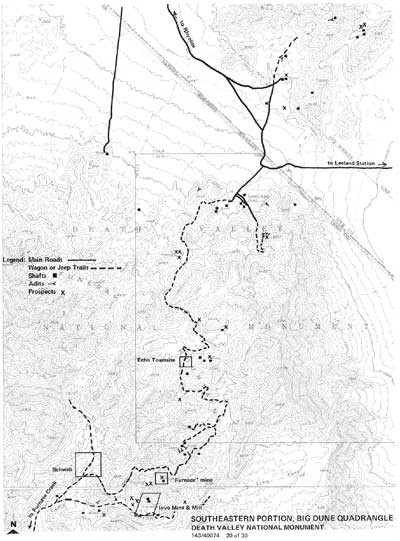

| Illustration 81-82. Top: Dumps of the Franklin Mine, site of the original 1871 discovery of silver ore. The floor of Death Valley, 5,000 feet below, can be seen in the background. Bottom: The one-stamp mill below the Franklin Mine, erected in 1910, but apparently never used. The Franklin Mine is over the top of the ridge in the upper background. The individual standing beside the stamp is six feet, two inches in height. 1978 photos by John Latschar. |

|

| Illustration 83-84. Top: One of the three dugouts located about one-half mile north of the Franklin Mine. This structure, which measures twelve feet by twenty feet, was divided into two rooms. The roof over the far room has been blown away, as the rocks which weighted down the tin roof had gradually disappeared. Bottom: Chloride City, viewed from the north. The town site itself was centered around the bare area in the center of the photo. The Franklin Mine is located on the south side of the ridge in the background, the 1916 Lane millsite is near the road visible in the right background, and the 1941 site mercury mill is to the right of the photographer. |

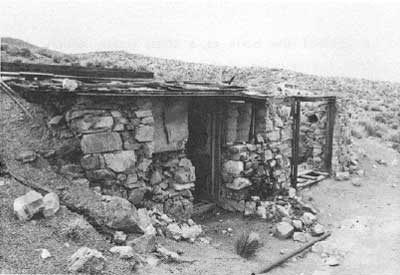

About one-half north of the Franklin. Mine is a group of three dugouts, obviously the homes of several miners during some stage of Chloride Cliff mining activity. The dugouts are lined up against the bank of a small wash, which shelters the structures from the ravages of the constant winds which sweep over the Funeral Mountains. The dugouts are constructed of native rock, stone, wood, and tin, and are in reasonably good shape. Although the historical data is unable to identify these dugouts with any particular phase of mining, bottles from a small dump down the wash date mostly from the 1930s, although some purple glass is evident. The relative intactness of these structures, one of which measures twelve feet square, and the others which are approximately twelve by twenty feet, would indicate that they were probably built in the 1930s.

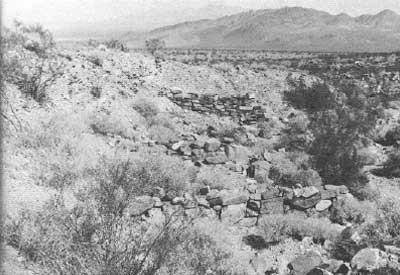

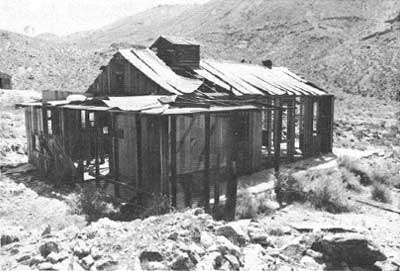

The third major grouping of structures is the site of old Chloride City. The town at its height in 1906 contained no more than four wooden structures, but two dugouts and numerous tent sites may be found in the area. Chloride City died in late 1906, when the local mines shut down for several years, and when mining returned to the area in the 1910s and the 1930s, the remnants of the building were used for whatever purpose seemed necessary. The wooden structures are now all collapsed, and have been stripped of most of their lumber. The largest of these collapsed structures, which undoubtedly was the boarding house, measures twenty-four by thirty feet, and the rest are about eight by twelve feet in size. The area around the old town site is heavily covered by prospect holes, adits and dumps, and it appears that the major mining efforts during the 1905-06 period took place in the general vicinity of Chloride City. Near one of the old adits, just south of the town site, is the grave of James Mckay, who died at an unknown age, at an unknown time, and of an unknown cause. His gravesite, situated in the midst of a long-forgotten mining camp, seems like a symbolic "tomb of the unknown miner."

|

| Illustration 85-86. Top: Chloride City, showing the remains of the boarding house. Bottom: Grave of James McKay, located about a quarter mile south of Chloride City. 1978 photos by John Latschar. |

|

| Illustration 87-88. Top: Ruins of the 1916 Lane mill, located just southwest of Chloride City. Photo was taken from the dump above the mill, showing the remnants of several concrete pedestals. The mill tailings are visible to the right front of the person in the photo, and the stone wall built to contain those tailings are just above his head. Bottom: Ruins of the 1941 mercury mill, showing the water tanks, and several levels of workings. 1978 photos of John Latschar. |

To the southwest of Chloride City, across the top of a small ridge, is the site of the 1916 Lane mill, built by McCrea and his associates. The mill is built on a medium-sized mine dump. A water tank was positioned on the side of a hill across from the mill, site, and a four to six foot high stone wall was built below the mill, to prevent the tailings from being washed down the mountain. The mill site itself occupies an area about thirty feet square, but only concrete foundations and posts remain to mark the site. Several adits, a leveled tent site, a dugout and an old frame and tin shack may be found in the vicinity of the mill.

Finally, about a quarter mile northwest of Chloride City, is the site of the 1941 mercury plant. There are more physical remains to mark the site of this mill, for a galvanized water tank, extensive concrete foundations, and the ruins of a brick furnace are easily identified. Although erosion makes it difficult to judge, the amount of tailings around this mill would seem to indicate a life of several months before the complex was destroyed by fire.

In summary, the structural remains in the Chloride Cliff area include three mill ruins, several dugouts, several wood and tin shacks, and the collapsed buildings at Chloride City. Together with the proliferation of mine dumps, adits and shafts too numerous to describe, these remains present an interesting panorama of mining efforts carried out in this region between the 1870s and the 1940s. Although the total output of all the Chloride Cliff mines is estimated to be only $35,000 during all these years, the variety of efforts represented in the area, together with the identification of the original 1871 Chloride Cliff Mine, make this property eligible for nomination to the National Register as a historic district. In addition to the remains described above, the ruins of the Big Bell Mine, situated one mile southwest of Chloride City, will also be included in the Chloride Cliff Historic District. The Big Bell Mine itself is discussed in a subsequent chapter.

The entire Chloride Cliff area cries out for protection. At present, there, are no attempts being made to protect the valuable and fragile historic resources remaining at the area, and the combined efforts of motorcyclists, four-wheel drive enthusiasts, bottle-hunters, and general scavengers are fast destroying the area. At least one of each type was seen in the vicinity when the author was examining the sites. The area should be thoroughly posted and regularly patrolled to discourage and prosecute destructive users.

In addition to protection, the Chloride Cliff district also presents Death Valley National Monument with a unique opportunity to interpret mining from the 1870s to the 1940s. The area is perfect for a self-guided tour, with visitors wandering the wind-swept region, stopping at various unmanned interpretive sites to reflect upon its long and varied history.

3. Keane Wonder Mine

a. History

in December of 1903, two prospectors wandered into the Funeral Mountains on the east side of Death Valley. Like so many others, these two men were among the horde of prospectors scanning the deserts and mountain ranges of southern Nevada for gold, spurred on by the. fabulous riches discovered shortly before at Tonopah and Goldfield. What brought them to this particular area is unrecorded, but perhaps they had heard about the old Chloride Cliff Mine, which had operated briefly in the Funeral Range in the 1870s.

At any rate, the two prospectors, named Domingo Etcharren and Jack Keane, found an outcropping of silver ore in the northern Funeral Range in December of 1903. The two men worked their discovery for several months, attempting to trace the outcropping to a silver lode, but they were unsuccessful. Then, quite by accident, Jack Keane discovered an immense ledge of free milling gold ore a short distance from the original silver location. The discovery was aptly named the Keane Wonder, and represented Keane's first major strike after eight years of desert prospecting.

Like the 1870 operators of the Chloride Cliff Mine, which was located only two miles above the new Keane Wonder, Etcharren and Keane were dependent upon Ballarat for supplies. But unlike 1871, eastern California and southern Nevada were prepared for a gold rush in 1904, and when the two men came into Ballarat in May of that year for a rest and re-equipment, news of their strike touched off a genuine gold rush. Other prospectors rushed to the Funeral Mountains to get in on the strike, and promoters began to negotiate with Keane and Etcharren for the purchase of their locations. By late May, the strike was "confirmed--that is, other prospectors and experts in the employ of mining promoters had examined the site--and Keane and Etcharren began to receive offers to sell their eighteen claims.

|

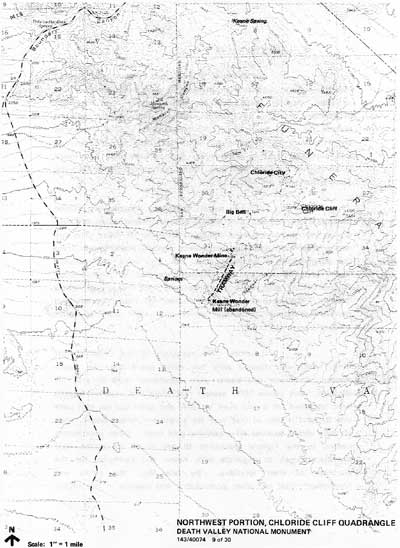

| Illustration 89. Map of Northwest Portion of Chloride Cliff Area. |

The two men, however, knew that they had something big, and decided to wait until the right offer came along. It did not take long, for within a few weeks the Keane Wonder was bonded to a well-known California mining operator, Captain J. R. Delamar. The terms of the bond called for Delamar to pay the locators $10,000 in cash immediately, for which Delamar obtained the rights to develop the locations for one year, with an option to purchase the mine at the end of that time for $150,000. The bond agreement was signed, sealed, and placed in the Inyo County Recorder's office on June 24, 1904, even though no one seemed to know for sure whether the mine was located in California or Nevada--a telling indication of the great lack of knowledge about the Death Valley region.

Delamar at once went to work, and shipped machinery and supplies to the mine. By the end of July he had thirty men working on the property. In the meantime, a decided rush was on to the Funeral Mountains, several other important discoveries had been made, and the Inyo newspapers reported that there "is a rush for the field from Ballarat and vicinity and pack jacks and canteens are in demand." By the end of July, one paper estimated that there were five hundred prospectors in the general vicinity of the new discovery. Two of these were "Shorty" Harris and Ed Cross, who were soon to discover the Original Bullfrog Mine. [9]

During the rest of 1904, Delamar's men feverishly worked the Keane Wonder Mine, racing against the one-year deadline to determine if it was worth the purchase price of $150,000. An assay office and a general office building were built at the site, and a wagon road was cut across the desert to within a mile of the mine, which was situated mid-way up the steep Funeral Range above Death Valley. By early 1905, their efforts to develop the mine were frustrated by the beginnings of the great rush to Bullfrog, which made horses and wagons almost impossible to obtain, and development work of necessity was slowed down. Nevertheless, enough teams were found to make the sixty mile haul from Ballarat, and fifteen men were still employed in driving two exploratory tunnels in March of 1905. The results of this work made the Keane Wonder look like a truly great prospect. "There is," reported the papers, "enough quartz in this mountain, and float, if it carries sufficient value, to run a 100 ton-a-day plant for twenty years."

By this time strikes were popping up all around the Keane Wonder. Stimulated both by it and the even greater Bullfrog strikes, literally hundreds of prospectors were swarming through the Funeral Mountains. In an effort to maintain some order and to record the numerous locations being made, the South Bullfrog District was soon created, encompassing within its boundaries and Keane Wonder Mine. Just to its north, the Chloride Cliff Mine had been reopened, the Big Bell had been discovered between the Keane Wonder and the Chloride Cliff, and numerous other mines began operations. Inevitably, these peripheral mines included one incorporated as the Keane Wonder Extension Mining Company.

As May 15th approached, when Delamar's bond on the Keane Wonder would expire, he started negotiations with Keane and Etcharren. In late April, he offered to buy the mine, but at less than the $150,000 stated in the bond agreement. Unfortunately for him, Keane and Etcharren had closely watched the development work done by his men during the past year, and they fully realized that they had a real mine on their hands. Such a thing happens only once in a lifetime, and they refused to accept a penny less than $150,000. Delamar either could not or did not want to pay that sum, and his option expired.

After Delamar's men left the property, Keane and Etcharren performed only sporadic work during the excessive heat of Death Valley's summer, while awaiting a new purchaser. They knew that their mine was too big for them to develop properly on their own, but all available investment money was being poured into the booming Bullfrog mines, and the Keane Wonder became almost forgotten. The two men, however, were patient and bided their time.

With the advent of cooler weather in September, Keane and Etcharren resumed work on their own. A small shipment of high-grade ore was sent to the smelter, and with the $28,000 which they received for it (which amounted to $1,867 a ton), they were able to employ a half dozen miners. Costs were comparatively low, since the mine could be worked through tunnels, thus avoiding the expenses of sinking and timbering shafts and hoisting the ore. With a bit of good luck, the shipment of occasional high-grade batches of ore would thus pay for the development of the mine on a small scale. With this plan in mind, the two men continued to work on their own through the remainder of 1905, employing five or six men, and waiting for the dust to settle around the Bullfrog boom, after which men with money would be able to see that their mine also had great potential. [10]

In early 1906, the prospectors' patience won out, as offers for the purchase of the mine were again made. L. L. Patrick obtained a bond for the property, similar to Delamar's of the previous year, with an option to purchase. Patrick immediately announced grand plans for the mine, including the erection of a 20-stamp mill at the foot of the Funeral Range, a mile from the mine and two thousand feet below it. Patrick and his men worked the mine for several months, while his engineers prepared surveys for an ore tram from the mine down to the mill site. But for an unknown reason Patrick decided not to exercise his option to purchase, and his bond expired in early March.

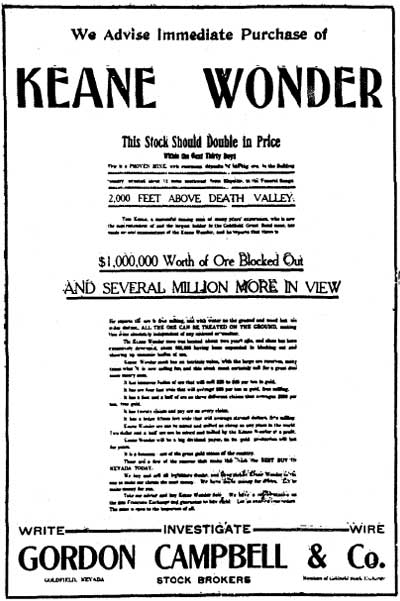

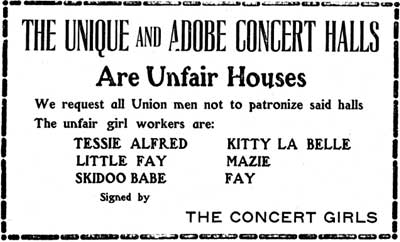

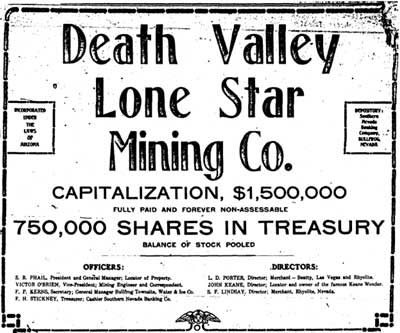

But by now promoters were standing in line for a chance at the mine, as soon as Patrick's bond expired, John F. Campbell and his associates jumped in. Campbell and his backers bought the Keane Wonder Mine outright, for a reported price of $250,000, $50,000 of which was paid to Etcharren and Keane in cash, and the rest given in form of stock in a company to be organized to develop the mine. The new company was incorporated in late March, with a capitalization of 1,500,000 shares. Jack Keane, who held a controlling stock interest, was elected president of the new company, with Campbell serving as vice president and Domingo Etcharren as secretary. The new company claimed to have forty to eighty thousand tons of gold ore on its twenty claims, and within a week, full page ads began to appear in the Rhyolite newspapers, offering stock for sale to the general public. The initial response was quite favorable, with Keane Wonder stock selling for 42¢ on May 4th, and 50¢ a week later.

|

| Illustration 90. Rhyolite Herald, April 6, 1906. |

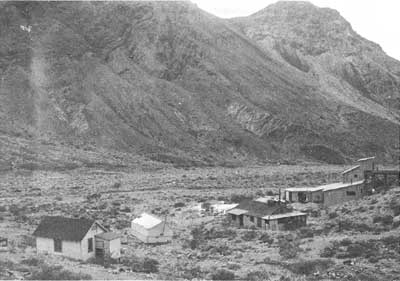

The new owners immediately resumed development on the property, and new ore strikes were soon made. Prospects looked extremely favorable for the company, for both wood and water were available within a reasonable distance from the mine, and the ease of tunnel mining indicated that development and extraction costs at the Keane Wonder would be relatively low. Within a short time the company had two mining camps established, one at the mine high on the side of the Funeral mountains, and the other located on the floor of Death Valley below. [11]

The Keane Wonder was by now receiving attention from papers as far away as Denver, Colorado. The mine had grown to twenty-two claims, comprising 240 acres of land, but even with the expenditure of $35,000 over the past year in development work, still only five of those twenty-two claims had been explored at all. But just when things looked brightest, disaster struck. The great San Francisco fire and earthquake of April 1906 effectively wiped out Campbell's fortune, which had an immediate effect upon the finances of the Keane Wonder Company. Development abruptly slowed down, and within a month reports were printed that Campbell was meeting in California with parties interested in buying the mine.

Campbell and his associates had no difficulty in finding a buyer. In late June, Homer Wilson, president of the Sildman Consolidated Mines Company of San Francisco, was in the Bullfrog District looking at various investment possibilities. On August 10th it was announced that Wilson and his associates had purchased the Keane Wonder Mine. The sale was heartily approved of by the local newspapers, which by this time had realized the financial distress caused Campbell by the San Francisco disaster. Wilson, who owned a string of mines in the Mother Lode country of California, was extolled as "one of the boldest and most successful operators" in California. The sale price was not released to the newspapers.

After several disappointments arising from previous sales, Jack Keane and Domingo Etcharren were now ready to sell out all their interests in the Keane Wonder, and this time they accepted full payment in cash, thus terminating their interests in the Keane Wonder Mine which they had discovered. Etcharren dropped completely out of sight and was never heard from again, but Keane's subsequent career can be sketchily traced. With the money from the sale of the Keane Wonder, Keane "who recently joined the ranks of those living on Easy street," invested in almost fifty claims in the Skidoo District on the west side of Death Valley. Within a few month's, however, Keane's luck turned sour. In September he was involved in a shooting affair in Ballarat, California, where after a night of drinking he wounded two local peace officers. Shortly after that he disappeared, to surface in Ireland in the fall of 1907, where it was reported that he was sentenced to seventeen years in jail for killing a man. The Rhyolite papers sadly commented upon this tragic end for one of the region's few lucky prospectors, but noted that when "drinking he usually resorted to his gun on very slight provacation." [12]

In the meantime, Homer Wilson and his associates went to work. The Homer Wilson Trust Company was incorporated, as a holding company for the Keane Wonder and other Wilson interests, and the new Keane Wonder stock was offered to the public. Advertisements in December of 1906 claimed that the first allotments of stock offered for sale at 50 per share had been oversubscribed in forty-eight hours, and that stock was now for sale from the company at 65¢ per share. Work was resumed at the mine in early November, and the company immediately ordered a 20-stamp mill and auxiliary equipment. The milling plant, announced Wilson, would consist of crushing by stamps, with amalgamation, concentration and cyanidation, and was expected to cost between $75,000 and $100,000. Wilson promised the press that his mill would be the first one in the Bullfrog region to begin operations.

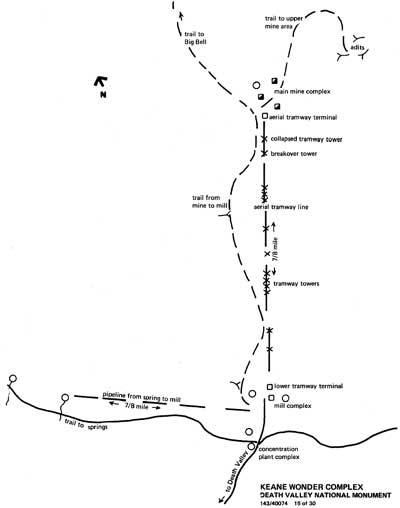

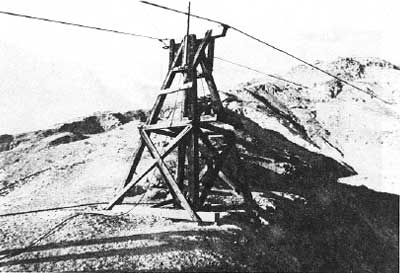

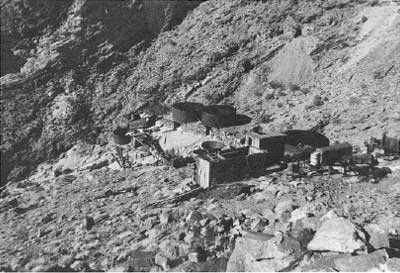

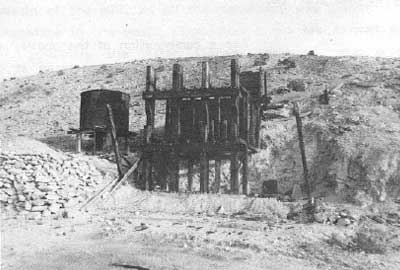

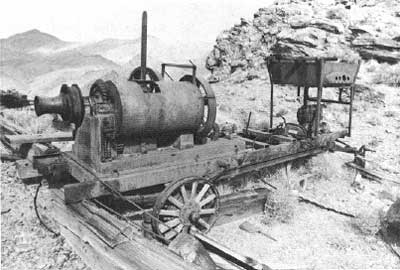

Ten men started preliminary grading work for the mill buildings in early December, and plans were drawn for a gravity tram to bring the ore down from the mine on the mountain to the mill site in the valley below. By late December, mill machinery began to arrive over the new railroad, including an 85-horsepower Coreless oil burning steam engine, which would be used to power the mill. The aerial tramway from the mine to the mill was surveyed, and the company decided to install a Riblet gravity tram, 4,700 feet long, wherein the loaded ore buckets coming down the mountain would pull the empty ore buckets and supplies back up to the mine. By the end of December, construction on both mill and tramway was under way, and in addition twenty men were still employed in the mine. The company announced that it had $650,000 worth of ore blocked out, which would suffice to feed the mill for several years. [13]

As 1907 began, luck stayed with the Keane Wonder Mine, sometimes in almost unbelievable proportions. The mine continued to look well, for as more tunnels were driven, more ore was found. Then, when some men began sinking a well near the mill site below the mine, they struck another gold ledge instead of water. The well was immediately turned into another working shaft. Twenty-five men were employed by the company in early January, and the foundations for the mill buildings were excavated.

During February, more mill machinery and equipment arrived over the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad. The machinery contract had been let to the Risdon Iron Works of San Francisco, and Walter Lyons, formerly employed by the rival Union Iron Works of the same city was hired as construction superintendent. The Porter brothers of Rhyolite, after intense competition, won the contract to haul some 255 tons of machinery, timbers and supplies from Rhyolite over Daylight Pass to the mill site, twenty-six miles away. As February and March progressed, machinery and supplies continued to arrive with regularity, and the Keane Wonder Mill began to take shape. As the framework for the main mill building began to rise above the desert in early April, the price of Keane Wonder stock rose with it, for investors were impressed by the final resources and energetic management of Homer Wilson. Keane Wonder stock was sold for 75¢ in early April, and 80¢ late in that month.

As equipment arrived, mill construction took priority over development of the mine, and all available labor was put to work at the mill site. The framework for the mill building was finished in April, the ore bins were built and the mortar blocks set. More men were added to the payroll, which reached $3,000 per month. Final costs for the mill were estimated at $85,000. At the same time, a group of men were put to work on the water supply for the mill, which was being developed in several different spots. As a hedge, the Keane Wonder Company purchased Keane Springs, about seven miles away towards the top of the Funeral Range, as well as the young townsite at the springs. The company also bought up several claims adjoining its own, in order to obtain a right of way for its aerial tramway between the mine and the mill, bringing its total holdings to twenty-six claims, comprising some 450 acres. Arrangements were made to extend a telephone to the mill site, from the Rhyolite-Skidoo line. As construction proceeded, stock demand rose, but few shares were offered for sale. "The holders of this stock are evidently willing to wait for the dividends which seem sure to come within a few months," surmised the Rhyolite Herald.

By mid-May, all the mill equipment and machinery had arrived, and most had been installed. In addition, the company had finished the construction of a new boarding house at the mill site, to accommodate the construction crew and the. future mill crew. Then, in July, with the mill essentially completed, the construction crews were shifted to the building of the aerial tramway. This would prove to be a long and laborious task, especially with the intense heat of summer, but the Keane Wonder Company pressed on, for it was in a decided race with the Montgomery Shoshone Company of Rhyolite to see who would have the first running mill in the Bullfrog region. The Keane Wonder was at a disadvantage in the race, for in addition to building a mill, it was also required to complete a tramway and many other auxiliary features. For example, in mid-July, a huge 25,000 gallon galvanized iron tank was built beside the railroad tracks in Rhyolite, to be used as a storage tank for the crude oil which would be hauled to the mill site to fuel the plant. According to the Bullfrog Miner, "This is the largest tank of the kind in the country."

But the construction proceeded well. By late July, the tramway towers were beginning to arise along the ridgeside, and the company predicted that the mill and tramway would be completed by September 1st. In the meantime, some miners had been put back below ground, and another strike of ore almost immediately resulted. Delays on the delivery of the huge tramway timbers slowed construction for a while in July and August, but other construction continued. The water and crude oil tanks at the mill were completed in early August, and the timbers for the tramway were laboriously dragged up the mountainside. Twenty-one thousand board feet of lumber were required for the upper tramway terminal, 28,000 for the lower, and 25,000 for the intermediate towers. The tramway had thirteen towers, with the longest span between them being 1,200 feet, and the vertical fall from top to bottom was 1,500 feet. During the height of tramway construction, the Keane Wonder Company employed no less than five mill wrights for framing the timbers for the terminals and tramway towers. Each tower rested upon a foundation measuring twenty-four feet square, in many cases blasted out of solid rock.

Despite the 105 degree temperature at the construction site in mid-August, the workers toiled on, with most work being accomplished during early morning and late evening hours. Finally, on September 14th, the last load of equipment for the towers was hauled out to the mill site, making a total of 1,500,000 pounds of freight which had been hauled from Rhyolite during the course of construction at a cost of $11,000.

Work was delayed somewhat in mid-September, when several men quit, stating that the food served at the Keane Wonder boarding house was "absolutely the worst ever put before a crew of working men on the desert." Mrs. Hull, the company cook, took exception to the accusation, and replied that "the provender is good and the parties making complaints are soreheads." Nevertheless, new men were found, and construction continued. In early October the tramway cable was stretched, and only the hanging of the buckets remained for the tramway to be completed. Homer Wilson arrived in town to witness the first days of the mill tests, and also to award a contract to the Porter brothers of Rhyolite for the transport of crude oil from the storage tank in Rhyolite to the mill site. Two tank wagons, holding twenty-one and twenty-seven barrels respectively, would make nine trips each per month, in order to satisfy the demands of the big steam engine. The tank wagons, which were owned by the Keane Wonder Company, were special heavy duty Studebaker models.

Finally, in late October, everything was ready for the machinery to be turned on for the first time. Homer Wilson, in an understandably pleased mood, told reporters that he hoped the 80-ton capacity mill would turn out $1,000 worth of gold per day when running at full speed. All mill tailings, he said, would be impounded, for the company expected to add cyanide tanks within a year in order to rework the tailings and thus extract the utmost in gold savings. In the meantime, the miners had 2,000 tons of ore broken down in the mine, ready to feed the mill. But due to the Panic of 1907, which had just hit the Nevada mining fields, Wilson was forced to make an emergency trip to Goldfield on October 27th, the day that the Keane Wonder Mill began to operate.

For the next month, everyone involved held their breath, waiting to see if the huge investment in labor and equipment would pay off. The equipment was turned slowly at first, as constant checks were made for defects in the machinery, and only forty tons were treated per day. But all the equipment worked well, and soon the tonnage was increased. On November 11th, the first bars of gold bullion were brought into Rhyolite, the result of the first three weeks run, and were estimated by one local paper to be worth $40,000. That figure was undoubtedly exaggerated, however, for the Keane Wonder Company did not announce its production figures, and another paper estimated the total output for all of November at only $25,000. But regardless of figures, the tramway and mill were evidently working well, and the company formally invited reporters and interested miners to visit the site and take a ride in its tramway.

In early December, a Rhyolite Herald reporter made such a visit. The mill was now running twenty-four hours a day, he reported, and was treating seventy to seventy-five tons per day. The ore being treated at the mill averaged $18 to $20 per ton, and the present mill equipment was saving 65% of the gold content. The tailings, which were being saved for later cyanidation, assayed at $3.95 per ton. Homer Wilson estimated the known ore reserves at 100,000 tons, and development work in the mine was increasing that figure faster than the mill could reduce it.

The ore bin at the upper tramway had a capacity of 100 tons, and an especially unique feature. Power from the gravity pull on the tramway was used to operate a preliminary ore crusher at the upper terminal, through which the rock passed before descending to the mill. In addition, a supplementary 13-horsepower gas engine was installed on the upper tramway terminal, so that the ore crusher could be operated when the tramway was idle. The tramway was supported by twelve towers and one breakover station. The highest tower was thirty feet, the lowest eighteen. The longest span between towers was 1,280 feet and was 500 feet above the floor of the canyon below. Each ore bucket on the tramway carried 600 pounds, and was loaded automatically. The material for the tramway included 95,000 board feet of timber and fifty tons of wire rope and terminal material, and the tramway rose on a grade of 1,000 feet per mile.

The ore buckets dumped automatically into the mill bin at the lower tramway terminal, which had a capacity of 200 tons. From there the ore passed onto suspended Risdon feeds, and under the Golconda pattern batteries, whose twenty stamps weighed 1,000 pounds each and dropped 100 times per minute. Inside amalgamation was by back plate and chock block with the ore passing from the screens onto a lip plate, and then falling into distributing pots and onto the apron plates. From the plates the pulp passed into the amalgam trap, and the sands went to the original classifier, with the coarse sands sent to two Wilfleys vanners and the fine sands to four Johnson vanners. Tailings were pumped into four Callow tanks, each eight feet in diameter, where 75% of the water was secured and pumped back into the tanks for use in the stamps. The tailings were impounded in dams and allowed to settle, with remaining water again recycled back through the mill. The amalgam was retorted and melted at the mill and finally converted into gold bullion.

Water for the mill was drawn from a well shaft 285 feet from the mill, and was pumped into a tank above the mill by an artesian pump. The mill itself was driven by a Corliss steam engine, with steam generated in a 126-horsepower Sterling boiler. The exhaust from the engine was used to heat a 100-horsepower Cochrane feed water heater, which heated the water to 210 degrees, thereby driving off the soda and other minerals which would have clogged the boiler. Crude oil was used to fire the boilers, and the works were lighted by electricity generated at the mill site.

The mill building was framed, and covered with galvanized iron. All the floors were concrete, with concrete foundations, mortar blocks and retaining walls. The tramway materials were from the Leschen Brothers & Company, a St. Louis outfit specializing in aerial tramways. Over forty different designs and combinations, said Wilson, were studied before the company finally decided upon this arrangement. Finally, the reporter concluded, the Keane Wonder Company had a fine camp established at the mill site, where Mr. and Mrs. Wilson lived. Other families included those of Vice-president and Mrs. Rogers, and mill superintendent and Mrs. Lyons. The Kimball brothers had established a twice-a-week stage line between Rhyolite and the mill, to satisfy transportation demands. [14]

|

| Illustration 91. The left half of the Keane Wonder Mill complex, which should be matched with the opposite photo. Note the piles of lumber and other materials, which would soon be used for the support buildings of the mine complex, the two small tent structures, and the large storage building. The cyanide plant, which would be built several years later, would stand on the slightly higher ground behind the large storage building. Photo from the Rhyolite Herald, 6 December 1907. |

|

| Illustration 92. The new Keane Wonder Mill, as photographed for the Rhyolite Herald in December of 1907. Although it is not a very good picture, it is one of the few remaining. The basic mill buildings have just been completed, but none of the support buildings, such as the building which later covered the lower tramway terminal (which is located behind the mill), have yet been erected. The tent houses in the foreground were boarding and bunk houses. |

But despite the excellent success of the Keane Wonder Mill, all was not well with the company. The Panic of 1907 hit the Nevada mining industry quite hard, and one of the earliest casualties was the State Bank and Trust Company of Goldfield, and its president, Thomas B. Rickey. When the State Bank and Trust failed and went into receivership in November of 1907, the effects upon the future of the Keane Wonder Company were made evident when the newspapers reported that the bank had loaned the company $200,000 for the construction of its mill and tramway. President Rickey promised that the loan would be made good, but as the Inyo Register pointed out, "The Keane Wonder is now practically owned by the State Bank and Trust Company," and the future of the company's finances was much in doubt.

But while waiting for the financial picture to become clearer, the Keane Wonder Mill continued to produce. It is difficult to give a reasonable estimate of mill output, since Homer Wilson was not in the practice of announcing bullion figures, but we do know that the mill was working steadily. Wilson brought in a bar of gold bullion to Rhyolite on December 7th, the result of twelve days' run, and the papers estimated its worth at around $16,000. Another gold brick was brought in on December 21st, estimated at $6,000. As a unique feature of the Keane Wonder operation, the gold bullion was shipped to the mint, which processed it and shipped back gold coins to the company, which were used to pay the Keane Wonder employees. The mill was still not running at full capacity by the end of 1907, due to difficulties in obtaining enough of a water flow to satisfy the mill demands. Average daily runs through the latter part of 1907 averaged seventy-five tons per day. But still, based upon a compilation of the more conservative newspaper estimates, the Keane Wonder Mill produced around $36,000 in gold bullion in 1907. [15]

As 1908 opened, the Keane Wonder Mill continued to produce, although the lack of an adequate water supply kept the mill from running at full capacity. Bullion estimated at $15,000 was brought in or January 9th, and another shipment estimated at $8,000 was sent to Rhyolite on February 5th. Even without being able to run full time, the mine and mill seemed to be operating most efficiently, for the entire costs of mining, traming and milling the ore was put at a mere $3 per ton. This efficiency, of course, was greatly helped by, the fact that the soft rock being mined at the Keane Wonder was being pulled out of horizontal tunnels and stopes, which alleviated the costly necessity of sinking and timbering shafts and of installing and operating hoisting machinery.

|

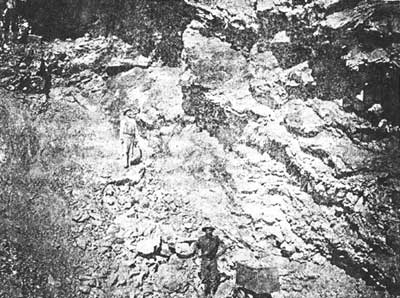

| Illustration 93. View of one of the working faces of the Keane Wonder Mine, showing the ease of mining. The ore at this point could be stripped directly off the face of the cliff, which saved the company thousands of dollars over the costs of tunneling, shafting, and timbering. From a booklet, "Bullfrong Mining District," published by the Rhyolite Chamber of Commerce, 1909. |

As could be expected, the troubles of the State Bank and Trust Company, which received wide publicity, caused a number of rumors to circulate concerning the Keane Wonder Company. The Inyo Register reported on February 13th that the mine and mill would close, due to those complications, but Homer Wilson hotly denied the rumor, stating that the mine had ore reserves sufficient to supply the mill for two more years. Two days later, as if to prove his point, Wilson brought in another gold brick estimated at $4,000.

By late February, the newspapers were able to begin untangling the affairs of the Keane Wonder Company and the State Bank and Trust. The Rhyolite Daily Bulletin reported that T. B. Rickey, the former president of the bank, had personally taken over the debt of the Keane Wonder Company to the bank, which amounted to $195,000. Since Rickey was also a heavy stockholder in the Keane Wonder Company, this seemed to bolster the future of the mine, for such a move would enable the Keane Wonder to avoid the long drawn out receivership settlement affecting the bank and all those connected with it. Further good news followed, for the discovery of an additional water source enabled the mill to begin running around the clock in late February. It immediately began to treat almost 80 tons per day, near full capacity, and Homer Wilson brought in another gold brick on March 5th, estimated at $7,500, bringing February's production to an estimated $15,000.

Further bullion shipments were made later in March, as an estimated $5,000 was brought in on March 19th, and another $1,700 on March 28th. A short time was lost for minor repairs, but the mill continued to function well. In late March, Homer Wilson, realizing that the continued rumors connecting the State Bank and Trust Company with his mine were having a detrimental effect, granted a long interview to a reporter from the Rhyolite Daily Bulletin.

The Keane Wonder, he said, had two years of ore supplies already blocked out, and further development work would undoubtedly increase those known ore reserves. The average ore in the mine, like that which had already been run through the mill, was around $16 per ton. The company would soon begin the construction of a cyanide plant to treat the mill tailings. At present the mill, without cyanidation, was saving about 62 percent of the ore content, and the addition of a cyanide plant would increase that savings ratio to 92 percent. When the plant was completed, Wilson hoped for a monthly production of $25,000 from the combined works.

Water shortages, however, were continuing to plague the company. Even with the addition of a new water supply, and with the unusual recycling arrangements built into the mill, full time operation was impossible. Thus the mill had settled into a schedule of twenty-four hour operation for four days, followed by sixteen hours for the next three, while the water supply was built back up.

Concerning the rumors connecting the mine and the bank, Wilson was most specific. The finances of the Keane Wonder Company, in his opinion, were in good shape. With the output of the property the last three months the company had paid off every cent of its indebtedness, and would be able to begin paying dividends the next month--unless, of course, such profits were put back into the expansion of the facilities, such as a new cyanide plant. The Keane Wonder Company, said Wilson, had absolutely no connections or entanglements with the State Bank and Trust Company. The mine did not owe the bank a penny, and whatever troubles Mr. Rickey was having involved only his personal stock in the Keane Wonder, and not the company itself. Rickey and Wilson together owned 875,000 of the 1,500,000 shares in the Keane Wonder, and whatever happened to Rickey's portion of those shares would have no effect upon the mine itself. In addition, the company still had 350,000 shares of treasury stock. These shares, which the company had never put on the market, could be sold at any time when the company faced financial difficulties. In summary, Mr. Wilson quite candidly put his mine into perspective. "We have not got what may be called a big mine or a high grade mine," he said, "but a nice little proposition that will clear good and dependable money every month in the year, and from the looks of things, for many years hence." [16]

April proved to be another good month for the Keane Wonder. Homer Wilson brought in three gold bricks estimated as being worth $30,000. The output for future months looked even better, for during April yet another source of water was located, which the company said was sufficient to supply a 60-stamp mill. Pipe line and pumping machinery were ordered, for the new water supply was 3,500 feet from the mine and 100 feet below it. Work on the cyanide plant, the company announced, would begin after the new pipe line was laid.

In addition, new ore bodies were discovered in the mine, which increased the company's ore reserves. Some of the new ore was high grade, and was called the best discovery in the history of the mine. Homer Wilson essentially agreed with that assessment, and stated that there "is perhaps enough ore in sight to wear out the 20-stamp mill that we now have in operation on the property." Even the announcement that a disgruntled stockholder named E. H. Widdekind had filed suit in the Esmeralda county district court, asking for a receiver to be appointed to the Keane Wonder Company, failed to dampen the enthusiasm surrounding the mine. Widdekind alledged "all kinds of crooked work," chiefly that Wilson had appropriated large amounts of the company funds to himself, but no one seemed inclined to believe the accusations.

During May, the mine and mill continued to produce, with an estimated total of $21,600. The decrease in bullion was due to continuing water difficulties, as the heat of summer cut down on the available water supply. Material for the new pipe line, however, was delivered in late May, and the company hoped to solve that problem shortly. But delays began to plague the. company in June. Leaks in the new pipe line delayed its utilization, although pumps and even a windmill was installed at different water sources. Still the twenty-five employees of the mine and mill managed to produce an estimated $15,200 during the month, with the mill running only about half the time. The long awaited cyanide plant was not yet started, due to the water problems.

In July, the extreme heat of Death Valley's summer began to take its toll. At the end of that month, the company announced that temperature had not been below 90 degrees for weeks, and was often above 124 even at midnight. Daily temperatures were usually up to 112 by breakfast and 124 by noon. Most men slept out of doors, and even eating was difficult, since the silverware was often too hot to handle. The boarding house cook flatly refused to allow a thermometer near his kitchen. The hot weather kept the water at near boiling temperatures, which made mill operation difficult. Still, over $11,000 was produced that month, and the ore reserves were enlarged. In addition, three new buildings were added to the camp, including a sixteen by forty-two foot residence for Homer Wilson and his family, a two-room office building and a new cook house. [17]