|

Death Valley

Historic Resource Study A History of Mining |

|

SECTION IV:

INVENTORY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES--THE EAST SIDE

A. The Bullfrog Hills

1. Introduction

In 1900 the state of Nevada was entering its third decade of depression. The incomparable Comstock Lode, which had stimulated the migration of 60,000 people into the Nevada territory, had financed a major portion of of the northern effort during the Civil War, had made Nevada into a state, and had spawned numerous smaller mining booms between the 1805s and the 1870s, had died out by 1880. Since then, no new strikes of importance had been found, the population of the state had fallen to 40,000, and the economy was suffering the effects of twenty years of decline. Some cynics even suggested that Nevada should revert to territorial status. Such was the fate of a state whose entire economy was built around the boom and bust cycle of a mining frontier. [1]

In 1900, however, the cycle was reversed. Silver was discovered at Tonopah that year, and massive high-grade gold deposits were located at Goldfield two years later. The great boom days returned to Nevada, and prospectors, spurred by dreams of untold riches, once again blanketed the mountains and deserts of Nevada. No more discoveries were made which rivaled the riches of Tonopah and Goldfield, but numerous smaller camps were established which bloomed briefly on the desert, dreaming of becoming another Virginia City. Rhyolite, the metropolis of the Bullfrog district, was one of these camps.

|

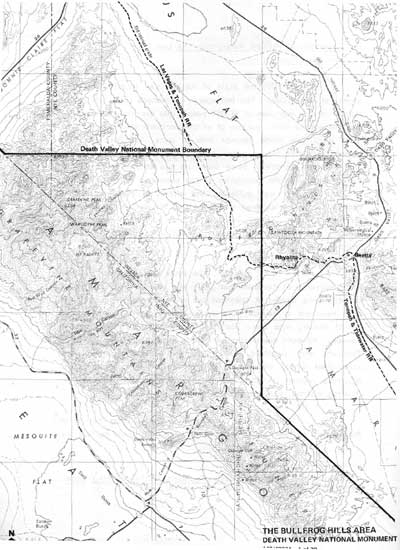

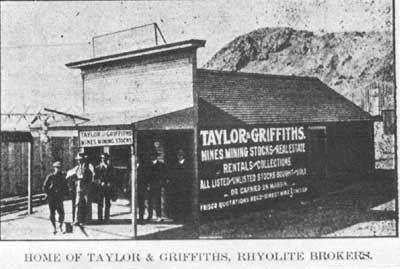

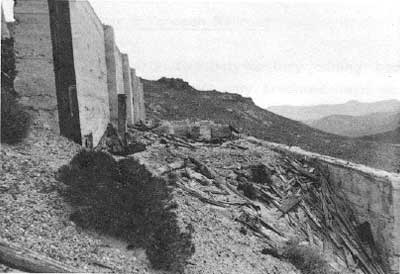

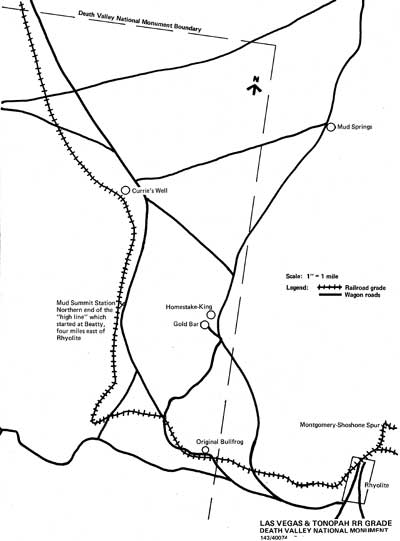

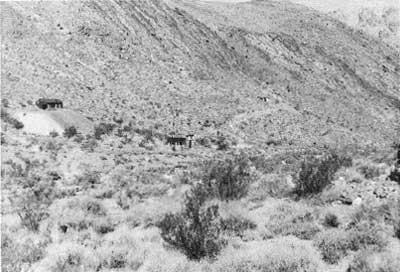

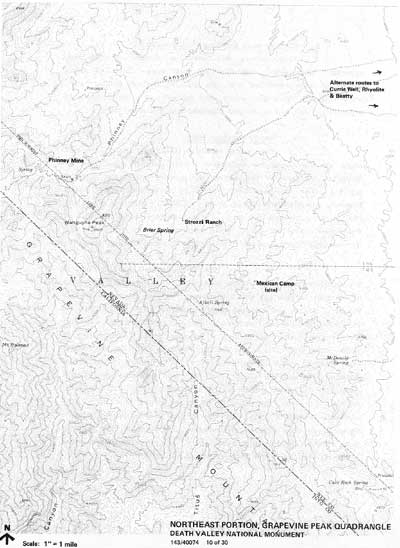

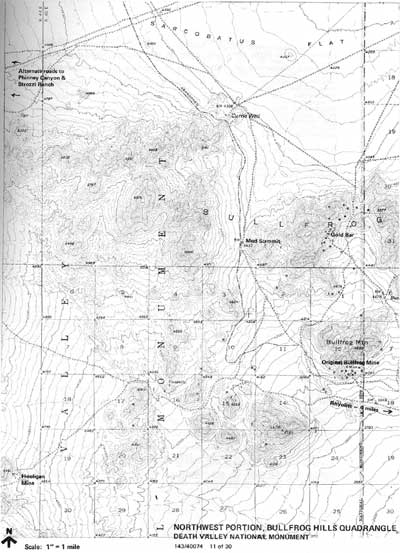

| Illustration 1. Map of the Bullfrog Hills Area. |

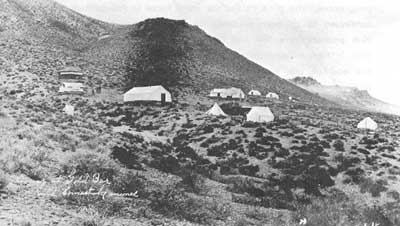

Gold was first discovered in the Bullfrog district in the summer of 1904. The initial finds were high-grade surface ore assayed at $700 per ton--just the kind of stuff to start a boom. Shorty Harris, one of the discoverers, later described the reaction of Goldfield when he and his partner, Ed Cross, brought in their samples:

I've seen many gold rushes in my time that were hummers, but nothing like that stampede. Men were leaving town in a steady stream with buckboards, buggies, wagons and burros. It looked like the whole population of Goldfield was trying to move at once. Timekeepers and clerks, waiters and cooks--they all got the fever and milled around wild-eyed, trying to find a way to the new "strike".

A lot of fellows loaded their stuff on two-wheeled carts--grub, tools and cooking utensils, and away they went across the desert, two or three pulling the cart and everything in it rattling. Men even hiked the seventy-five miles pushing wheelbarrows.

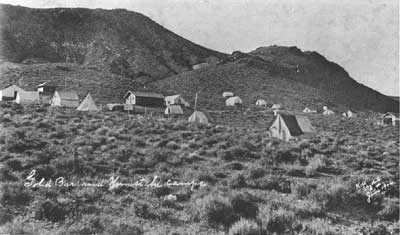

When Ed and. I got back to our claim a week later, more than a thousand men were camped around it, and more were coming every day. A few had tents, but most of them were in open camps.

That was the start of Bullfrog and from then things moved so fast that it made us old timers dizzy. [2]

Although Shorty Harris was guilty of much romanticizing in his later interviews, events did indeed move fast. Towns sprang up overnight in competing locations. Amargosa was laid out on September 30th and had sold 35 lots within three weeks. Beatty, to the southeast, was located on October 20th, and the towns of Bullfrog, Bonanza and Rhyolite were started by competing townsite companies in November--all within a few miles of each other. Amargosa reported 1,000 lots sold before the town was two months old, some for as high as $200 each, and by November the town boasted three stores, four saloons, two feed lots, restaurants, boarding houses, lodging houses, a post office and 35-40 other tent buildings. Prices, of course, were in proportion to the boom atmosphere and the costs of freighting 70 miles from Goldfield. Lumber for building was scarce and sold for $100 per 1,000 board feet, while hay for prospectors' burros and teamsters' mules went for $100 a ton.

The boom continued through the spring of 1905. Thirty teams a day left Goldfield for the Bullfrog district in January, and one traveler counted fifty-two outfits arriving in the district during one day in March. Confusion reigned supreme, especially for prospectors who left town for a few days in March, to find upon their return that the entire town of Amargosa had picked up and moved a few miles south to the town of Bullfrog. Bonanza's citizens had the same experience, as their town was moved to Rhyolite. Mining claims changed hands furiously, for ground near a publicized claim was worth $500 to $2,000, even if a pick had yet to strike the earth. By May, Rhyolite counted twenty saloons, a sure sign of wealth. [3]

|

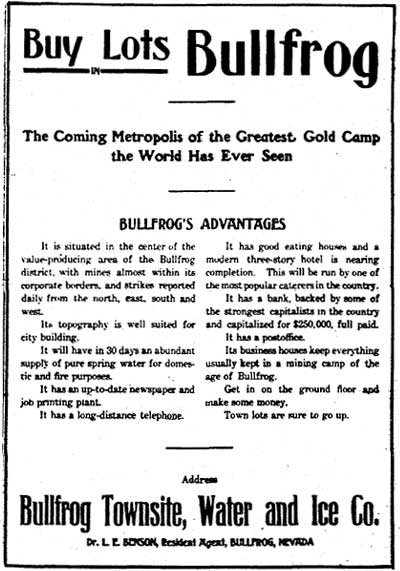

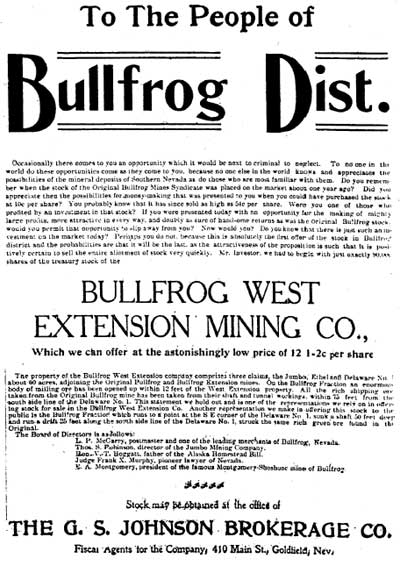

| Illustration 2. Early advertisement from the town of Bullfrog. From the Bullfrog Miner June 9, 1905. |

By late spring, the dust had settled a little, at least to the point where one could leave home overnight and expect the town to be in the same location when returning. Rhyolite and Bullfrog, located only three-fourths of a mile apart, had become established as the leading towns of the district, with Beatty, four miles to the east, running a poor third, and Gold Center barely surviving. Four daily stages connected the district with the outside world, post offices were running at Beatty, Bullfrog and Rhyolite, lots in Rhyolite which sold for $100 in February were selling for $4,400, and wheel and faro games were going twenty-four hours a day. "It reminds one of the old times," remarked one prospector. In addition, Rhyolite, Bullfrog and Beatty each had a bank, and each had a weekly newspaper. The Bullfrog Miner printed its first issue on March 31st, the Beatty Bullfrog Miner on April 8th, and the Rhyolite Herald on May 5th.

The boom kept pace through June. 3000 people were estimated to be in the district, the telephone line was completed to Bullfrog and Rhyolite, and the telegraph office opened. Over 300 messages were sent over the wires on the first day of operation, mostly to Goldfield brokers and stock dealers. By the first anniversary of the district in August, both Bullfrog and Rhyolite had their own piped-in water systems, Rhyolite had yet another bank, and the two towns had a population of 2,500, with another 700 at Beatty and 40 in the tent city of Gold Center. The Rhyolite Herald listed 85 incorporated companies working in the district. [4]

The pandemonium subsided somewhat in 1906, as the rush phase of the boom slowly turned into the more controlled phase of development. 165 mining companies were reported working in the district, and all had hopes of developing another mother lode with just a few more feet of digging. Rhyolite gradually won the battle with Bullfrog and by spring had emerged as the metropolis of the southern desert, when Bullfrog's store, saloons and newspaper moved up the hill to Rhyolite. Not one, but three railroads announced plans to construct lines into the district.

|

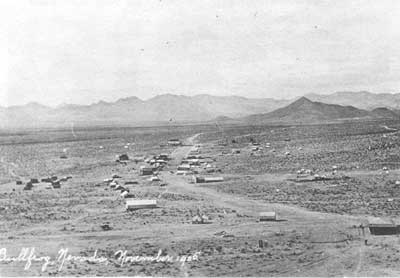

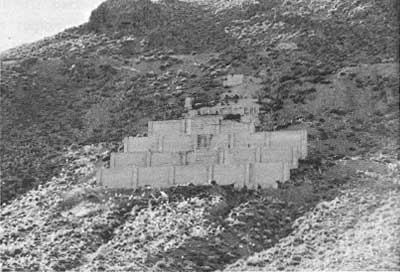

| Illustration 3. Bullfrog, Nevada, November 1905. Courtesy, Nevada Historical Society. |

|

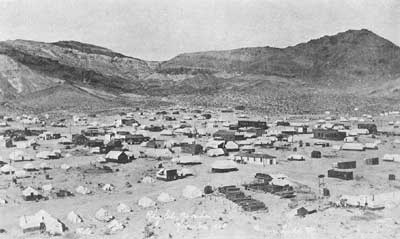

| Illustration 4. Rhyolite, Nevada, November 1905. Courtesy, Nevada Historical Society. |

Then, the first hint of disaster struck, with the earthquake and fire of San Francisco. Feverish developments slowed momentarily, as miners, owners, and promoters waited to see what effect the destruction of the west coast's financial center would have upon their fortunes. The boom spirit was still too prevalent, however, for the effect to be prolonged, and with the promise of financial aid (if needed) from mining promoter Charles Schwab, the bustle returned to camp. By the end of 1906, Rhyolite seemed assured of its self-proclaimed title of Queen of the Desert, when the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad completed its tracks into town. With the advent of cheaper rail freightage rates, the camp was certain to add to its monthly payroll of $100,000, and to continue its development. [5]

The year of 1907 was another good one. Fifty cars of freight per day were arriving over the Las Vegas & Tonopah in February. The town had grown to a population of 3,300, and lots at the heart of Rhyolite were selling for $10,000. A school census was taken which showed 250 children of school age, so a wooden schoolhouse was built, as was a concrete and steel jail for older folks. The Rhyolite Stock Exchange was incorporated and opened on March 25th, to ease the effects of feverish stock trading on the over-worked telegraph wires to Goldfield and San Francisco. In June, the Bullfrog-Goldfield Railroad came into town, opening rail connections with the north, and in September electric power was brought into town over the poles of the Nevada-California Power Company. The power was hooked into the already-wired homes, stores and offices of Rhyolite, as well as into the machinery of the big Montgomery-Shoshone mill, which soon began operations. Another newspaper, the Rhyolite Daily Bulletin appeared to compete with the district's three weekly papers. Production figures for the district went over $100,000 for the first time during the month of September, and the arrival of the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad the next month augured even more prosperity. [6]

|

|

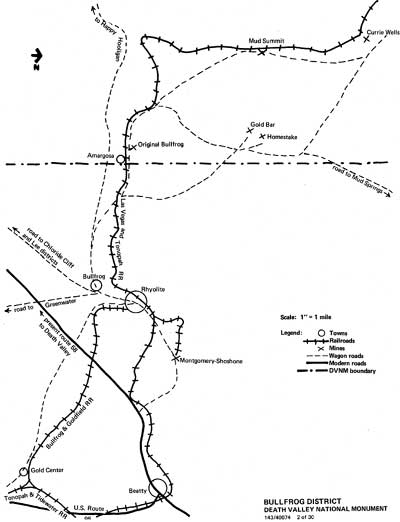

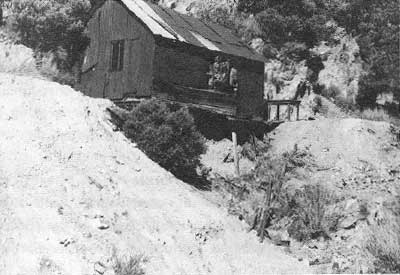

Illustration 5. Home of Taylor & Griffiths, Rhyolite

Brokers. Mining was the name of the game. For those who were not lucky enough to own their own mines, stock dealing was the next best thing. The firm of Taylor & Griffiths, one of Rhyolite's leading brokerage houses, was the site of much dealing, speculation and stock promoting. Photo from Rhyolite Herald, 15 June 1906. |

|

| Illustration 6. Prospecting in Death Valley was not a venture to be taken lightly. This victim, who was never identified, was found in the valley in 1907. Prospectors who found him estimated that he had been dead for two days. Photo courtesy of Death Valley National Monument Library, Neg #1138. |

Even the panic of 1907, which some would call a depression, did little to dampen the spirits of Bullfrogers. Newspapers noted, almost with wonder, that the panic seemed to affect the Bullfrog district much less than it did other mining camps in Nevada and California. The local banks were forced to issue script for a few months, due to the shortage of cash, but the local merchants gladly accepted it--even advertised for it--and the panic was put down to the manipulations of greedy eastern financiers. Despite the panic, property values sky-rocketted during 1907, and the year-end tax rolls reflected the prosperity of the young town, which was assessed taxes on almost two million dollars worth of real and personal property. [7]

1908 followed suit. The year opened with the big Montgomery-Shoshone mill treating 200 tons of ore per day, and with the promise of more mills to open soon, thus increasing the district's production and prosperity. To house all this money, the grand three-story, $60,000 John S. Cook Bank Building was completed in January. By February, all the banks were back on a cash basis, and reported that they had needed only half the amount of script which had been printed for use during the Panic. Production soared as new mills and mines went into operation, reaching an estimated $170,850 in the month of April. By September, the Bullfrog district ranked as the third largest producer in the state of Nevada, trailing only Goldfield and Tonopah. The Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad finished its magnificent passenger station in June, which immediately became one of the showcases of the southern Nevada region. By the end of the year, the Rhyolite Herald estimated the total production for 1908 as close to $1,000,000.

Construction continued apace, as the three-story concrete and stone Overbury building was completed in. December at a cost of $50,000. Now at its height, Rhyolite fairly bustled with activity. The newspapers enthusiastically claimed a population of 12,000, although a more probable estimate would be 8,000. The town now had an opera house, a new $20,000 concrete and steel, two-story school building, hotels, ladies' clubs, and even a swimming pool. The large concrete and stone buildings which dominated the main streets were flanked by hundreds of wooden stores, offices and residences, although a few late-arrivals still lived in tents on the outskirts of town. The Western Federation of Miners' local union, with its healthy membership, union hall and hospital, threatened to surpass the local at Tonopah. Rhyolite even had a manufacturing base of two foundaries and machine shops, and the Porter Brothers, leading merchants, had built their original tent store into a imposing building complete with freight elevators and a stock worth $100,000. Dane halls and brothels, ever a sign of prosperity in a mining camp, spilled over from their assigned districts on several occasions, drawing the attention of the town council. Rhyolite and the Bullfrog district, it seemed, had arrived. [8]

|

| Illustration 7. Rhyolite near its height in February 1908. The Overbury building, and the John S. cook Bank building, to its right, dominate the city. The tracks of the Bullfrog and Goldfield Railroad may be seen in the lower right and lower left corners. The lumber yard of the Tonopah Lumber Company is in the lower right, next to the city jail. The school house is not yet built. Various mines can be seen in the background, and the former city of Bullfrog is at the extreme left background. Photo courtesy of Nevada Historical Society. |

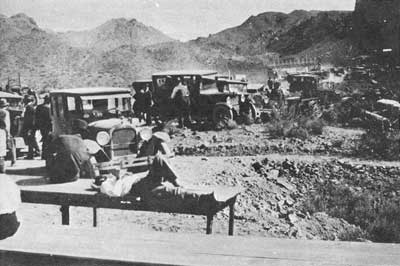

In the meantime, the Rhyolite and Bullfrog boom were having much the same effect upon the surrounding Death Valley country as Goldfield and Tonopah had had upon the entire state. Spurred by the Bullfrog boom and dreams of wealth, prospectors swarmed out of Rhyolite into the hills and deserts of southeastern Nevada and southwestern California. Backed by flush Rhyolite merchants and promoters, these men examined the countryside as it has never been examined before or since. For a while, the results seemed almost too good to be true, for strikes and mining camps blossomed out of the wilderness almost everywhere one could see. On the east side of Death Valley, the entire South Bullfrog district grew up around the Keane Wonder mine, while farther to the south arose the boom camps of Lee, Echo, Schwab, Greenwater, Gold Valley and Ibex. Farther to the west, across the Death Valley sink, prospectors out of Rhyolite found and established the mines and camps of Emigrant Springs, Skidoo, Harrisburg and Ubehebe. All these camps looked upon Rhyolite as the metropolis of the desert, and Rhyolite merchants, teamsters and outfitters, located at the railhead, profited immensely from being situated at the distribution center for the region.

As usual, however, the gold fever which swept the country contained more fever than gold. Some of the smaller camps died almost as soon as they were born, leaving little more than a ripple on the surface of time. Some, like Greenwater, spent all their energy on booming, and when the dust had settled, nothing was left to be seen. Most lasted a year or two, or even three. But with the exception of Skidoo and the Keane Wonder, all the smaller camps died before Rhyolite, and the fate of the offspring presaged the fate of the parent.

|

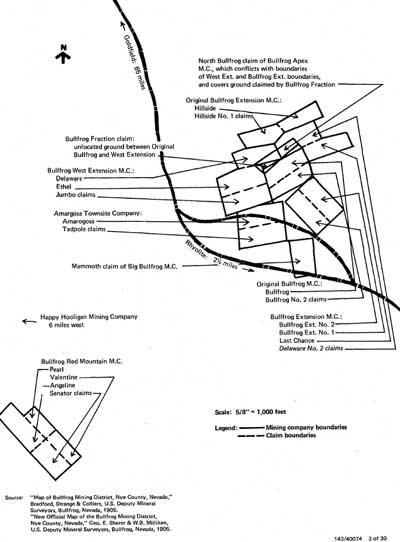

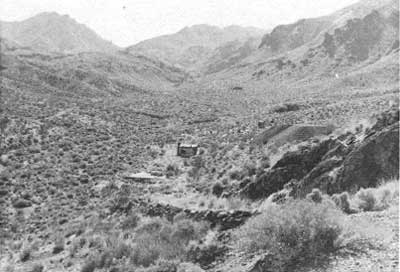

| Illustration 8. Sketch Map, Bullfrog District. |

On the surface, Rhyolite seemed as robust as ever in early 1909, and the citizens of the town even started a movement to split the county in two, making Rhyolite the county seat of the southern portion. Such ambitions, however, were hopeless, for the cracks were already appearing in the facade. Although the boom spirit had carried the Bullfrog district through the San Francisco disaster and the panic of 1907 without appearing to harm the camp, underlying problems were beginning to surface. Investor confidence was weakened by the financial difficulties, a fatal blow to any mining camp. Two of the three Rhyolite banks had closed by the end of 1909, and shady dealings involving two of the district's most promising mines further shook investor confidence. The Montgomery- Shoshone mill continued to mill its low-grade ore throughout 1909, but there is nothing romantic about low-grade ore. A brief new boom at Pioneer, to the north, seemed to arrest the process of decline for a short time, but a disastrous fire roared through that camp before it was even built, and it never recovered.

The process of decay is harder to document than that of boom, since the local newspapers would never, dare print any discouraging news, but the evidence was there. The Rhyolite Daily Bulletin was the first newspaper to close, printing its last issue in May of 1909, and the Bullfrog Miner followed suit in September. The December tax rolls told the real story. When the time came to ante up for county taxes, owners of 156 properties--or 28 percent of the total tax base--elected to quietly leave town and let their properties be confiscated by the county treasurer, rather than spending more money in a losing cause. As the Mining World summed up, "Mining operations in the Bullfrog district were rather dull last year." [9]

The camp plodded through 1910, struggling to keep alive, and hoping that some prospector would make the strike which would bring back the days of prosperity. Their hopes were doomed, however, and when tax time rolled around again, 168 taxable properties (44 percent) were left to the care of the county treasurer, as their owners had departed. The First National Bank closed its doors that year, the fast bank to leave Rhyolite.

The trend accelerated in 1911, when the Montgomery-Shoshone, the only mine to make any significant production in the district, finally shut down in May. The 1911 tax rolls again showed owners of 1.18 properties (43 percent) leaving town rather than pay taxes, and the Mining World sounded the death knoll. "The Bullfrog district is almost deserted, save by a few lessees, who at intervels [sic] make a small production . . . . The Montgomery-Shoshone, after demonstrating that ore averaging $6 a ton could be profitably milled, has closed down, having exhausted its pay ore." [10]

The Bullfrog district, too, was exhausted. The town and camp did not die with a bang, and hardly with a whimper. Companies who had money left in their treasuries held on to properties, hoping for a comeback, and several dozen intrepid souls stayed on in Rhyolite, eeking out existence by leasing mines and extracting occasional small shipments of ore. The great days, however, were definitely gone forever. The Rhyolite Herald finally gave up and closed down in June of 1912, and the town slowly died.

Periodic efforts were made to reorganize and rework the mines on a small scale, which kept Rhyolite from becoming a complete ghost town for several years, but none were successful. In 1914, the Las Vegas & Tonopah discontinued service to the town, above the protests of the few remaining citizens. In 1916, the Nevada-California power company cut off electricity to Rhyolite, and began to salvage its poles and wire. The Inyo Register described the once thriving town in December of that year: "Rhyolite, once a camp claiming several thousand population, is practically a deserted village . . . the movable buildings have been moved away from time to time, and the process is still going on. At present it is contributing to the upbuilding of the camp of Carrara. . ." By 1920, although a few companies and individuals still held on to their Rhyolite properties, hoping against hope for a revival, the camp was completely deserted." [11]

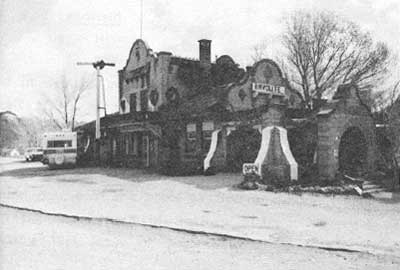

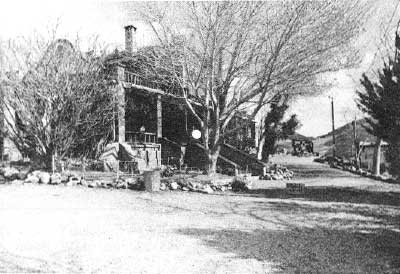

And so Rhyolite was slowly dismantled to serve the needs of new boom camps, and the cycle was completed. Although small-scale efforts were made to revive the camp from time to time--including one during the fall of 1978--the good days were gone. Today, the crumbling remains of its once imposing structures, together with its picturesque location, make it one of the west's most popular ghost towns. Ironically, Beatty, 4 miles to the west, which played little sister to Rhyolite throughout the boom years, was saved from decline by the construction of Nevada Highway 95, and today that little town of several hundred thrives on the trade of tourist, military personnel and truckers traveling between Las Vegas and Reno.

|

| Illustration 9. Rhyolite, 1978. John S. Cook Bank building. Photo by John Latschar. . |

|

| Illustration 10. Rhyolite, 1978. Rhyolite jail. Photo by John Latschar. |

|

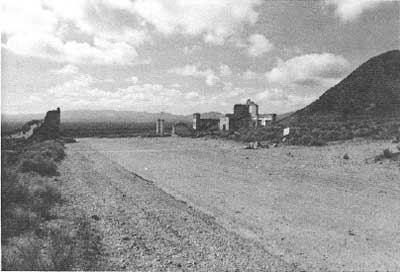

| Illustration 11. Golden street, Rhyolite, looking south from John S. Cook Bank building. Facade of Porter Brothers store on left, ruins of Overbury building on right. Photo by John Latschar. |

|

| Illustration 12. Rhyolite's pride, the $20,000 school building. Completed after the boom had left the Bullfrog rose, the building was never used to capacity. Photo by John Latschar. |

All was not in vain, however. The Bullfrog district produced $1,687,792 worth of ore in the four short years between 1907 and 1910, doing its part, along with the other small camps and the bonanzas of Goldfield and Tonopah, in pulling Nevada out of its two-decade slump. Without the stimulus of this early twentieth-century mining boom, of which Rhyolite and the Bullfrog district were a distinct part, Nevada would not have had the new economic base with which to survive the great depression, and to emerge as a prosperous mineral, tourist and military state of today. [12]

Just as important, without the boom and bust days of Rhyolite and the surrounding territory, we would not have the opportunity today to study, appreciate and preserve the memories of these early twentieth-century mining camps. And, thanks to the Bullfrog boom, Death Valley National Monument is rich with such a heritage of bygone days.

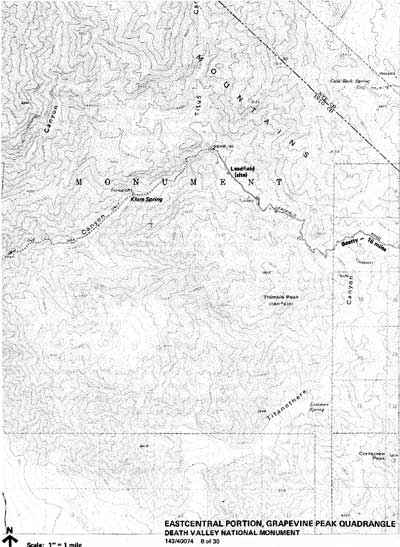

2. Original Bullfrog Mine

a. History

In the late summer of 1904, two wandering prospectors happened to meet at the Keane Wonder Mine, on the east slope of Death Valley. Ed Cross, the first, was an occasional prospector who had participated in mining rushes from time to time. Cross, however, was an "amateur" prospector, since he had a home and farm in Long Pine, California, to which he would return between forays. Attracted by the Goldfield boom, Cross was on his way towards that region, and had stopped off at the Keane Wonder to look over the country surrounding that recent discovery.

The other prospector, Frank "Shorty" Harris, was a veteran desert rat. Shorty bragged that he had attended every mining rush in the country since the 1880s, including those of Leadville, Coeur d'Alene, Tombstone, Butte, British Columbia, and others. Like most prospectors, Shorty had, as yet, nothing to show for his efforts. He had already been through the initial Tonopah and Goldfield booms, but had gotten there too late to locate any close-in ground. Now, like Cross, Shorty Harris was determined to give the Goldfield territory another look, and the two men teamed up.

Like countless other prospectors who were scurrying around the deserts, Cross and Harris dreamed of finding another bonanza like those of Goldfield and Tonopah. As the two men trugged across the Amargosa Valley, that dream loomed large before them, for they were about to make the discovery which would initiate the great Bullfrog boom, and which would change forever the history and territory of southwest Nevada.

Accounts of the next few days vary wildly, as romantic tales of big discoveries are wont to do. Both Cross and Harris repeated their versions in later years many times over, and it is difficult to find any two versions which agree. Apparently Shorty persuaded Ed to make a detour on the way to Goldfield, in order to examine some rock outcroppings which he had noticed on an earlier trip. There, on the east side of the Amargosa Valley, the discovery was made. Both men knew at first glance that they had found something big, but how big would have to be determined by the Goldfield assayer's report. Quickly locating a claim, staking the ground, and naming the mine the Bullfrog, for the distinctive mottled green ore, the two men set out north for Goldfield, to record their claim, have their samples assayed, and to celebrate.

The rock samples indicated that the mine had ore worth over $700 to the ton--truly bonanza stuff. News of the discovery soon spread through Goldfield, and by morning the rush to the newly named Bullfrog District was on. In the meantime, Ed Cross went north to Tonopah to record the claim there in addition to Goldfield, since no one knew whether the mine was located in Esmeralda or Nye county. By the time Ed got back, Shorty was half-way through a six day drunk, sometime during which he sold his share of the Bullfrog mine. Cross later claimed several times that Shorty got no more for his share than $500 and a mule, although Shorty once claimed to have received $1,000, and thirty years later said he got $25,000. At any rate, Shorty Harris was out of the picture. Like most old-time prospectors, he had spent most of his life looking for a gold mine, and had sold it for a pittance when he found it.

Ed Cross was more business-like, as he reported to his wife. After several deals feel through, Ed sold his share to a group of mining promoters for cash and a share of the stock in a company formed to exploit the mine. Ed later claimed to have received $125,000 for his share of the mine, but that figure is probably inflated. But whatever the exact amounts, both Cross and Harris had sold out--one for drink and the other for stock certificates. Which would prove to be the better deal was yet to be seen. It is certain, however, that neither of the two prospectors who started the great Bullfrog boom made much profit from their discovery--but that is nothing new in the history of mining. [13]

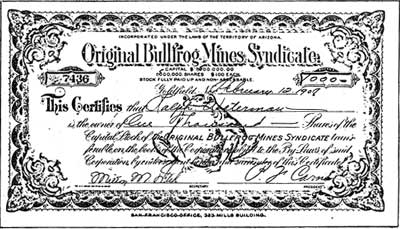

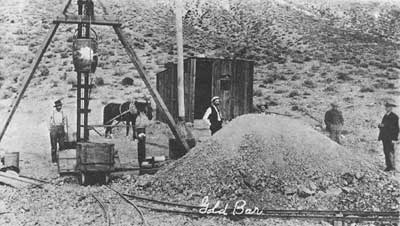

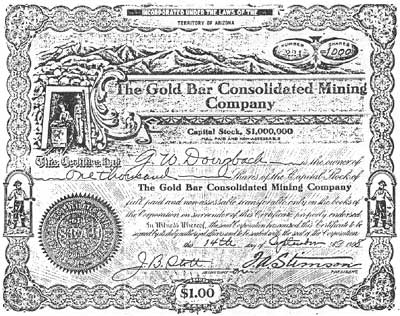

By early fall, the Bullfrog boom was in full bloom. Tents, towns and prospectors surrounded the area of the Bullfrog Mine, as prospectors and promoters rushed to get in on the ground floor. In short succession, mine after mine was discovered in the vicinity, and the Bullfrog District became the talk of the west coast. In the meantime, the Original Bullfrog Mines Syndicate, organized to operate the original discoveries, was incorporated by the Goldfield promoters dealing with Ed Cross, and actual mining was started. The company advertised a capital stock of 1,000,000 shares, with a par value of $1 each, but they did not say how much actual cash was placed in the treasury to finance the development efforts. As events proved, it wasn't enough. Ed Cross was given a seat on the board of directors of the company, as befitted the owner of one sixth of the mine.

Initial development through the fall and winter of 1904 were promising. The company reported ore assaying as high as $818 to the ton, and began sacking high-grade ore for shipment to Goldfield smelters. On March 23, 1905, the original Bullfrog Mine made the first big shipment out of the new district. Ore estimated to be worth $10,000 was escorted through Rhyolite by five armed guards and the Rhyolite band. The Original Bullfrog Mine, symbol of the entire Bullfrog district, was now a shipper and a producer. More good strikes were made in the shafts and tunnels through May and June; sixteen men were employed at the mine; a 15 horsepower gasoline hoist was ordered to enable deeper sinking; and the mine superintendent expressed the hope that shipments of high-grade ore would pay for all development costs, thus saving a strain upon the company's treasury. By August of 1905, the superintendent estimated that the company had between $750,000 and $1,500,000 worth of ore in sight in the mine. [14]

|

| Illustration 13. Certificate for 1,000 shares in the Original Bullfrog Mines Syndicate. Courtesy Dr. Richard Lingenfelter. |

The Original Bullfrog Mine continued to reflect the optimism of the entire district throughout the fall and winter of 1905. As shafts and tunnels went deeper, ore veins continued to show profitable values in gold, even though no rich shoots were found, such as the early surface discoveries. The Bullfrog District became so famous on a national level, that the United States Geologic Survey decided that it was worth examining. Frederick L. Ransome, an eminent western mining expert, made a study of the district's geologic formations and mines during the fall of 1905. Since Ransome was the first detached, outside observer of the district, his conclusions are of interest. The district, he wrote, was predominantly a low-grade proposition, and would have trouble making a profit, due, to problems of transportation and water supply. After the first publicized shipments, such as that from the Original Bullfrog Mine, none of the mines planned to make further shipments, due to excessive costs, until the railroads arrived. In essence, he concluded, the Bullfrog District was not the bonanza it liked to believe it was, but the mines could be made to pay on a large-scale basis, given careful and economical management. Nor was Ransome more impressed with the Original Bullfrog Mine than with others. "Some bunches of rich ore have been found," he wrote, "but the mass as a whole is of very low grade." [15]

|

| Illustration 14. The Original Bullfrog Mine in the summer of 1905. The short-lived tent city of Amargosa may be seen in the distance. Photo from Sunset Magazine, August 1905, p. 321, courtesy Nevada Historical Society. |

|

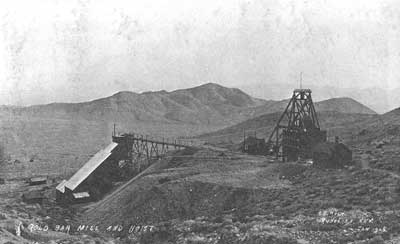

| Illustration 15. Original Bullfrog Mine, November 1905. Photo courtesy of Nevada Historical Society. |

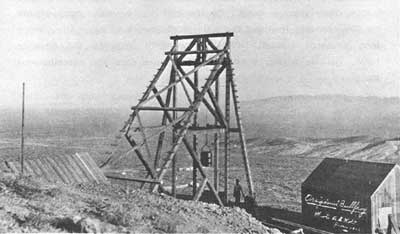

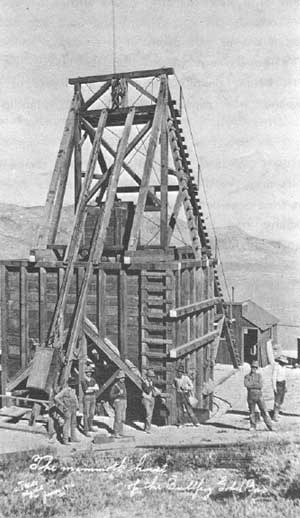

Happily for the Bullfroggers, however, Ransome's report was not printed for another two years, and the district hummed along merrily in the meantime. The Original Bullfrog Company continued to get encouraging results from its development works, and applied for a U.S. patent to their claims in January of 1906. A distinguished mine superintendent was hired away from the famous Gilpin County district of Colorado in the late spring, and the company installed a gas hoist and gallows frame on its property, in order to facilitate deeper mining. Even the brief financial panic brought about by the San Francisco earthquake and fire failed to slow development work, and William Ress celebrated his first anniversary as proprietor of the Original Bullfrog boarding house in May.

After examining the mine and its future prospects, Samuel Newell, the new superintendent from Colorado, decided that he would be there long enough to settle down, and set home for a bride. Mrs. Newell arrived in August and moved out to the mine site to live with her husband. Unfortunately, the summer climate of the Nevada desert did not agree with her, and she died in late September of "desert fever." [16]

|

| Illustration 16. Original Bullfrog Mine near its peak, June 1906. The new large gallows frame, with its bucket hoist, dominates the picture. Photo courtesy of Nevada Historical Society. |

The tragic loss of his two-month bride failed to diminish the energy of superintendent Newell. With the arrival of cooler weather in October, development was increased at the mine. The main shaft was now 250 feet deep, the mine was employing two shifts, of miners, and landlord Ress was feeding 30 miners, most from the Original Bullfrog. By November the shaft was down to 300 feet, and although no rich ore had been found since, the shaft had left the surface, the newspapers reported "encouraging values," a vague description at best. By the end of the year, improvements on the property included the main shaft, two working shafts, and a long crosscut tunnel. Physical property included the gasoline hoist, gallows frame, a small orehouse, ore cars and miscellaneous tools.

In the meanwhile, another development had taken place. On October 26th, Ed Cross had taken a lease from the company to work a 200 by 300 foot tract of the Original Bullfrog claim. Leasing at this stage of the mine's development could only mean that the company directors no longer felt that it was financially feasible to maintain a monopoly on development rights to its own property--a sure indication that things were not looking good. Cross, in a typical lease, was given one year to work the property and take out ore, while paying the company a royalty on any profits he was able to make. Cross had good luck initially, and by the end of 1906 was employing twelve men on his lease and had built an office. [17]

As 1907 began, the Original Bullfrog Mine had already seen its best days. Even though the railroad had now arrived, making possible the shipment of lower grade ore, the mine was not able to gain a profitable status. Development work continued throughout the year, by both the company itself and by Ed Cross on its. lease, but time was running out. The initial treasury fund was almost depleted, and the advent of bigger and more promising mines in the district discouraged stock sales. Shares in the Original Bullfrog Mines Syndicate, which had sold for 25¢ in November of 1906, had fallen to 74¢ by July of 1907. Desperately, the company continued, hoping to find that elusive high-grade vein which would make the mine a boomer once more, but hopes were doomed.

Ed Cross, despite his limited success on his lease, saw the handwriting on the wall, and decided not to renew the lease when it expired. Finally, the Panic of 1907 dealt the death-blow to the Original Bullfrog mine. With the treasury stock depleted, and with several of the leading owners facing extreme financial difficulties brought on by the panic, there were no more funds for-development work in the mine. On August 26th, the mine was closed and the employees laid off. The company's president issued a statement claiming that the closure had nothing to do with the financial crisis, but no one held their breath while waiting for the mine to reopen. For the rest of the year, the mine was not worked, and when tax time rolled around in December, the company let its property go on the delinquent roll, rather than pay $46.20 in taxes. Shares of Original Bullfrog stock were now selling for 3¢ each. [18]

In the spring of 1908, the mine was reactivated, but on a small scale. No longer did the superintendent announce grand plans for future development works, or the building of mills. Rather, the mine limped along on a very small scale, attempting to extract enough ore to cover operating costs. Leasing arrangements were sought, in order to bring more money into the treasury, and several individuals were lured by the magic of the Bullfrog name. Superintendent Newell managed to make several shipments of ore, but in small quantities--total April production, for example, reached the grand sum of $350, while lease-holders managed to ship $790 worth of ore in May.

Even these low figures did not reflect profits. One shipper, who had ore worth $160 a ton from a Bullfrog lease, paid over $20 to the railroad for shipping charges and over $37 to the Goldfield smelter for reduction charges, leaving him with a profit of $103 for his labor, before he paid the Original Bullfrog Company its royalty. By now it was clearly evident, as Ransome had pointed out several years before, that the Original Bullfrog Mine was a very low grade proposition, which could not be profitably exploited under present conditions. By the end of 1908, both stockholders and the company had come to agree with that assessment. Stock sales had slumped to 1¢ per share, and the company again could not find the money to pay its $34.65 in county taxes. Still, hoping against hope, several tease-holders hung on. [19]

In March of 1909, the Rhyolite Herald in its grand pictorial supplement, gave a long history of the discovery and developments of the Original Bullfrog mine, sadly concluding that The work has not proceeded . . . to the point of placing the property in the regular producing list." This was as far as a Rhyolite newspaper was willing to go towards admitting that the mine was dead. The Nye county treasurer, however, was willing to go farther, and in August of 1909 seized the movable property of the company in consideration for two years of unpaid taxes. Still, some hardy and hopeful individuals were willing to risk a few months' labor in the hope of finding the elusive green ore, and the property was working sporadically on a leasing basis.

By 1910, when it was becoming apparent that the entire Bullfrog District was dying, the Rhyolite Herald indulged in that favorite speculation of what-might-have-been. After discussing the early glory days of the district and the Original Bullfrog Mine, when high-grade ore was being shipped under armed guard, the Herald lamented: "If that kind of stuff, which ran up into the many hundreds of dollars per ton, had stayed in the Original instead of pinching out, the story of Bullfrog would be "another tale than what it is." True, but, Although the boom days were now definitely over, hope still persisted, as it can only do in a mining camp. In 1912, the success of a neighboring mine provoked rumors that the Original Bullfrog would be reorganized and reopened, but nothing happened. Small time operators continued to work the ground in 1913 and 1914, through leases. The patented claims of the mine lay on the delinquent list of the county tax roll, for want of anyone to pay, back taxes and reclaim the land. In 1917 a group of promoters incorporated the Re-Organized Original Bullfrog Mines Syndicate, but again nothing came of that effort. [20]

Nothing is harder to kill than the mystique of a name, especially a name such as the Original Bullfrog, with its intimate connections with the glorious boom and bust of the Bullfrog district. Time and again, throughout the following years, miners, prospectors, promoters and even movie stars were attracted by the prevailing mystique of the Original Bullfrog Mine. Surely, they thought, there must be something there, if this was the mine which started the whole thing. Their efforts were met with various degrees of middling success.

In the late 1920's the New Original Bullfrog Mines Company was organized and fitful shipments were made for several years before the enterprise folded. In 1930, Roy Pomeroy, a Hollywood executive, put together an organization with the backing of contemporary movie stars, and bought the Original Bullfrog as well as several other mines in the district. The Nye County treasurer, however, was soon listing all those properties once again on the delinquent tax roll.

In 1937 the Original Bullfrog, along with other mines, was purchased by the Burm-Ball Mining Company, which operated for several years, extracting small-scale shipments, before leasing them to other operators. These lease-holders operated intermittently through the 1940s and into the 1950s, but without any significant success. In 1955, one E.J. Kingsinger bought the mine, and like the Burm-Ball, continued to pay taxes on it, without deriving much benefit. In 1961, Kingsinger sold the mine to the H.H. Heislers, an old-time couple who moved back to Rhyolite and settled into the old Las Vegas and Tonopah passenger station. The Heislers in turn sold out to the Nevada Minerals Exploration Company in 1974, and the claims were again sold in 1976, to Boyce Cook and Lenard Cruson. [21]

So lived and died the Original Bullfrog mine. Considering its history, which saw only insignificant production and small-scale mining efforts, the mine itself would hardly be worth remembering. It was, however, much more Than just a mine--it was and is the symbol of the entire Bullfrog mining district, and all that that entails. The Original Bullfrog Mine was the spark which lit the Bullfrog boom, and that boom was in turn responsible for several other booms, the building of two towns, Rhyolite and Beatty, and the transformation of the entire history and economy of a large portion of the southwestern Nevada region.

And what of the two lonely prospectors who made the discovery? Shorty Harris went on, as most old-time prospectors did, to hunt again for gold in the desert. Amazingly, Shorty found gold a second time, at Harrisburg, on the western rim of Death Valley. Again, however, Shorty was unable to capitalize upon his discovery, and he died in 1934, alone on the desert, still looking for gold, and with little but his burro and his blanket to his name. Ed Cross, after giving up on his lease at the Original Bullfrog, returned to his home and farm in California and died at his daughter's house in 1958. [22]

b. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

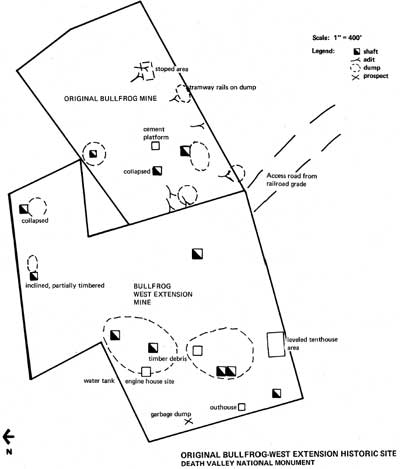

Due to the close proximity of the Original Bullfrog Mine to the workings of the Bullfrog West Extension Mine, the physical remnants of the two mines have been confused more often than not by recent studies. Since the mines were owned and operated, in recent years, by identical parties, the discussion of the historic structures, together with conclusions and recommendations, will be found at the end of the West Extension section.

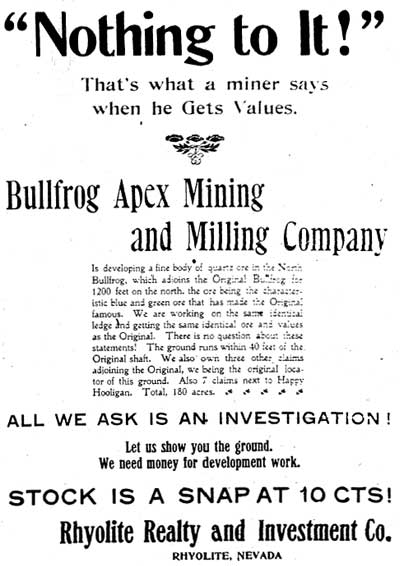

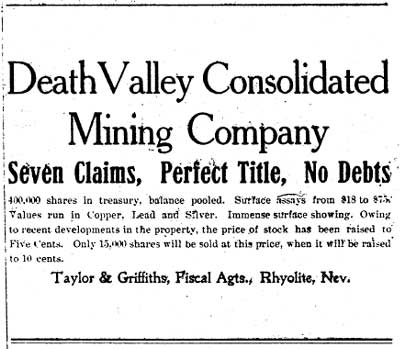

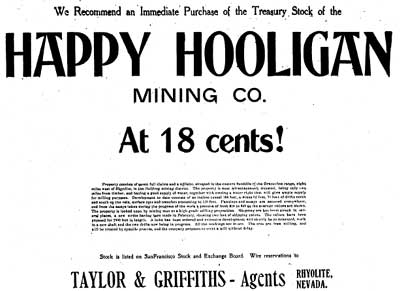

3. Miscellaneous Bullfrogs and Tadpoles

One of the first rules of the mining game is that one must get in on the "ground floor" in order to make money. If possible, an experienced prospector will hurry to the scene of the latest strike, locate ground as close as possible to it, and form a company with a similar sounding name. Between 1905 and 1910, this game was played to perfection by various and sundry miners and promoters in the Bullfrog District, as ninety companies were incorporated with the magic word "Bullfrog" somewhere on their letterheads. A few of these companies were in the vicinity of the Original Bullfrog, most--but not all--were within the boundaries of the Bullfrog District, and all hoped to lure stockholders' funds by advertising their proximity to the big strike. Some of the companies even went so far as to try mining.

A goodly number of these miscellaneous Bullfrog companies located ground within the present boundaries of Death Valley National Monument. Some, like the Bullfrog Winner Mining Company, the Bullfrog Western Mining Company, the United Bullfrog Mining Company, the Bullfrog Plutos Mining and Milling Company, the Bullfrog Gold Note Mining Company, and the Bullfrog Jumper Company, never did more than locate their claims, incorporate a company, sell stock to gullible investors, and never sank a pick into the ground. [23]

Other "close-in" companies were more interested in actually mining. Among these were a group of assorted Bullfrog mines which surrounded the Original Bullfrog on all sides, much like ants around a pool of honey. These companies, all of which were located and incorporated soon after the beginning of the Bullfrog rush, all sank shafts as close as possible to the Original Bullfrog claims, hoping that the peculiarities of geologic formations would cause the rich green ore found by Harris and Cross to dip and angle into their properties.

Of the seven companies which surrounded the Original Bullfrog ground, six were utter failures, and one--the Bullfrog West Extension--got lucky, for the unpredictable Original Bullfrog ledge penetrated its property. Although this seems like a high rate of failure, it was about the norm for the risking business of mining. The Bullfrog West Extension was the earliest of the mines which sprung up around the Original Bullfrog, thus emphasizing another mining dictum that the "firstest gets the mostest." As an example of an unusual success, its story will be told later. The other six mines were not so fortunate, and the following are the brief tales of some ill-fated companies which attempted to cash in on the Bullfrog bonanza.

a. Bullfrog Extension Mining Company

On August 25th and 26th 1904, a group of prospectors located two claims, the Delaware #2 and the Last Chance, on the north and east sides of the Original Bullfrog.. Together with the Bullfrog Extension #1 and #2, on the southeast of the Original Bullfrog, these four locations were incorporated in February of 1905 as the Bullfrog Extension Mining Company. The incorporation was the usual one, with 1,000,000 shares of stock offered to the public at a par value of $1 each, and it was backed by San Francisco financiers. In May the company had enough money in its treasury to begin mining, and by June a six-man crew had sunk an inclined shaft 75 feet into the ground. Development continued through the summer and fall, and in November the company was the proud owner of a 25-horsepower gasoline hoist, a frame office building for the mine superintendent, and a 141-foot shaft. By January of 1906, the company felt confident enough to advertise that it had a "magnificent quartz" ledge on its property which was "conservatively estimated" to be worth $500,000.

|

| Illustration 17. Sketch Map, Bullfrog claims, 1905. |

The promising developments at the Bullfrog Extension were halted by the San Francisco earthquake and fire in mid-April of 1906, and the mine was idle from then until June. Even though stock in the company was selling at its all-time high of 13¢ per share in late June, work was again halted for unknown reasons, and was not resumed until late October. By the end of 1906, although the company was still delving for ore, no significant discoveries had been made. Still, the company readily paid its county taxes of $24.86, assessed on personal property consisting of a 25-horsepower gas hoist, a twelve by sixteen-foot frame engine house, and a small office building, one ore car, and miscellaneous tools. [24]

Developments continued during the first part of 1907, as the company vainly attempted to find traces of the Bullfrog ore on its property. For a few months, prospects looked good, as described in the Bullfrog Miner on March 29th. The Bullfrog Extension, it reported, was "sinking at the rate of two shifts a day on a practically sure thing." Stockholders shared the optimism of the company and the newspaper, as the price of Bullfrog Extension stock was still holding at 12¢ per share in April. The panic of 1907, however, which hit the Bullfrog district in the fall, had a decided effect upon the fortunes of the company. The stock, after dropping from 12¢ to 5¢ in one month, had completely disappeared from the trading board by October. For a mining concern heavily dependent upon stock sales for operating cash, this was a disastrous blow.

The company rallied, however, and on November 1st announced an assessment of 24¢ per share of stock, payable to the secretary by December. Stockholders were thus faced with the choice of paying 2¢ a share more into the company treasury in an attempt at saving a mine whose stock was then worthless, or of forfeiting their shares to the company. (Assessment was illegal in Nevada, due to many past abuses, but the Bullfrog Extension was incorporated in Arizona, a more permissive state.) The assessment was partially successful, for the company was able to raise enough cash to pay its 1907 taxes--although they were paid late--but not enough was collected to pay for any future development works. The mine lay idle throughout 1908, and the company was forced to call for another assessment of 14: per share in December of that year. This time so few stockholders responded that the company was not able to pay its taxes, and the property of the Bullfrog Extension Mining Company entered the county's delinquent tax rolls [25]

In 1909, one last attempt was made to revive the fortunes of the Bullfrog Extension. This time the owners had no hope of raising enough cash to operate on their own, so in June of that year they advertised in the hope of attracting lessees. It would seem strange that the Bullfrog Extension would still be attempting to develop a mine in 1909, since the Original Bullfrog--the catalyst of the district--had already died. The neighboring West Extension property, however, was uncovering good ore, so the Bullfrog Extension changed its emphasis, and advertised its potential as a neighbor of the West Extension, rather than as a neighbor of the Original Bullfrog.

The advertisements were successful, and the property was leased in October. The new promoters then advanced a scheme which was absolutely fantastic, even for the Bullfrog district. The lessees incorporated not one, but three separate leasing companies, each of which had a lease on a different section of the Bullfrog Extension ground. The promoters then placed a long and confusing advertisement in the Rhyolite Herald attempting to explain their scheme. Potential stockholders were invited to invest in each of the three companies, which jointly held a three-year lease to the Extension property. Although the leasing companies were incorporated separately, they would then develop the Extension mine on a combined basis. As an extra added bonus, the purchasers of the first 50,000 shares of stock in each of these companies would receive, "free of cost," an equal number of shares in the Bullfrog Extension Mining Company--a promotional gimmick of no real risk, since Bullfrog Extension stock had been worthless for two years by this time.

The leasing scheme, as fantastic as it was, enabled the company to raise enough cash to hire a miner to do the annual assessment work on the Bullfrog Extension property, and to pay the 1909 county taxes of $18.00. Too few investors, however, could be fooled all the time, and the leasing companies folded before doing any work. The property was idle throughout 1910, although the company still retained enough cash to pay for the annual assessment work and the $18.00 in county taxes. By September of 1911, the company had finally given up hope, and the gas hoist and gallows frame were dismantled from the Bullfrog Extension property and shipped to Rawhide, for installation on a promising mine in that district. It was a very typical fate for mining equipment, buildings, tools, and anything else of value in a dying mine. [26]

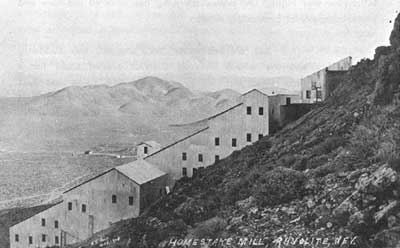

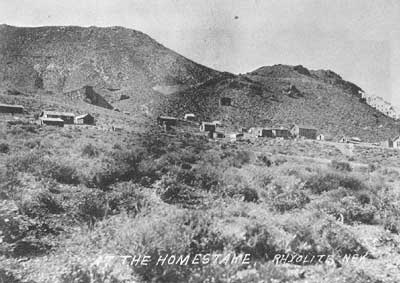

b. Big Bullfrog Mining Company

Located in the south of the Original Bullfrog, this mine had its inception in August of 1904, when "old man" Beatty, a local small-time dry rancher for whom the town of Beatty was named, located the Mammoth claim. Beatty soon sold out to a group of San Francisco financiers, who incorporated the Big Bullfrog Mining Company in 1905. The company owned just the one claim, but nevertheless formed the usual organization, with 1,000,000 shares of stock, par value $1. Developments commenced, and by the end of 1905 the company boasted of a 16-horsepower hoisting engine, and a 2-horsepower blower engine for the ventilation of its 120-foot shaft. The company was described as "exhibiting good ore" in a Rhyolite newspaper, whatever that meant.

Developments continued on an optimistic level in early 1906, as the company succeeded in finding some ore which assayed as high as $180 per ton. Stockholders, on the basis of this discovery, offered to sell. their stock for 14¢ a share, but no one was willing to buy. In March the company announced that it had uncovered a body of milling grade ore worth $14 a ton. Excitement mounted, since $14 ore was enough to make the Big Bullfrog a paying proposition, provided that great care and economy was taken, and that the ore deposits proved to be massive enough to warrant a large-scale operation.

In April, however, the San Francisco disaster drastically undercut the fortunes of the Big Bullfrog Company. The superintendent halted work at the mine when he learned of the calamity, and did not resume operation until the middle of September. The company then reported that "satisfactory progress" was being made through October and November, but no more ore bodies were found. At the end of 1906 the company held assets of one 16-horsepower engine, an engine house and gallows frame, several ore cars, and mining tools, for which it paid $29.32 to the county in taxes. [27]

The Big Bullfrog Company opened 1907 with a flair of development work, sinking its shaft to the 250-foot level, and opening up two ledges, with "fair values exposed." By March, however, the flair had definitely fizzled, for as the Bullfrog Miner wrote, the mine had "no material values." "Last week work was suspended for unknown reasons," continued the paper, as if the absence of any paying ore was not reason enough to close the mine. Stock in the mine slowly settled to 14 a share, and then disappeared from the trading board altogether, as it became evident that the mine would never again reopen. The Big Bullfrog had breathed its last, and with the exception of annual assessment work done in January of 1908, no further word was heard from another failed venture. [28]

|

| Illustration 18. The Big Bullfrog Mine in November of 1905. Note the gallows frame, the ore bucket, and the engine house. The dumps of the Original Bullfrog Mine may be seen between the legs of the gallows frame, and a few tent buildings of Amargosa are just to the left. Photo courtesy of Nevada Historical Society. |

c. Bullfrog Fraction

In December of 1904, Len P.: McGarry, mining promoter, stock dealer, and president of the Bullfrog West Extension Mining Company, noticed that the ground claimed by his company did not coincide with the boundaries of the Original Bullfrog. Between the Bullfrog claim of the Original Bullfrog company and the Delaware and Ethel claims of the West Extension, there lay a parcel of land, 1.7 acres in all, which was unclaimed. McGarry immediately located and recorded this ground as the Bullfrog Fraction claim. Then, interestingly enough, he sold it to outside mining promoters instead of selling or deeding it to his own company. Although this would seem to be a clear conflict of interests, such moves were not that unusual in the cut-throat business of mining.

Fractional claims are the bane of miners, and the delight of lawyers, and this one was no exception. Hardly had the new owners started to work, when their claim was disputed by the owners of the Bullfrog Apex Mining Company, owners of the North Bullfrog claim, whose boundaries conflicted with those of the Fraction, as well as those of the West Extension and the Bullfrog Extension. When the Apex company filed for a patent to the North Bullfrog claim in May of 1906, both the West Extension and the Bullfrog Extension filed adverse actions against the granting of the patent. Then, when high grade ore was found on the Fraction claim in June, matters got even more serious. For a while, the big companies tried to settle the matter by furiously working the ground in question, with the Bullfrog Fraction caught hopelessly in the middle. Then, in July, the West Extension and Bullfrog Extension both filed suit in court against the Bullfrog Apex Company, and a long legal battle ensued. The Rhyolite Herald correctly surmised that the struggle would be lengthy and costly for all concerned. "If they fight it out someone is bound to lose, while all will be put to great expense," wrote the editor. "Think it over, gentlemen, think it over."

The gentlemen involved, however, had already thought it over as much as they wished, and during the remainder of 1905 and for most of 1906, the case wound its way slowly through the Nevada court system. In the meantime, the owners of the Bullfrog Fraction, surrounded by litigants which desired their ground, continued to develop their claim, and continued to find good ore leads. As their claims grew more valuable, and as the court battles grew more involved and more expensive, it became clear to them that they could no longer protect their claim by themselves. Accordingly, in November of 1906, they gave up and sold the Bullfrog Fraction to the West Extension Company. That company in turn incorporated the West Extension Annex Company to develop the Bullfrog Fraction claim, and began to operate the two mines as one.

The Bullfrog Fraction thus disappeared as a separate mine, and became part of the West Extension holdings--where it would originally have been had the president of the West Extension, Len P. McGarry, seen fit to benefit his company rather than his pocketbook two years previous. As a bonus to the West Extension, and as a great aid in its fight against the Apex, the Bullfrog Fraction was granted a patent (which had been applied for by the previous owners) in March of 1907. [29]

d. Bullfrog Apex Mining and Milling Company

The Bullfrog Apex Mining and Milling Company was incorporated on August 4, 1905 by a group of promoters headed by J.J. Fagan and E.L. Andrews. The incorporation was a rather typical one, listing capital stock of 1,000,000 shares, par value $1 each. The company listed itself as the owner of 15 claims, only one of which was ever worked--the North Bullfrog. There was only one problem with the North Bullfrog claim: it intruded into the boundaries of the Delaware claim of the West Extension Company, the Delaware 4$2 claim of the Bullfrog Extension Company, and completely covered the small parcel of ground known as the Bullfrog Fraction.

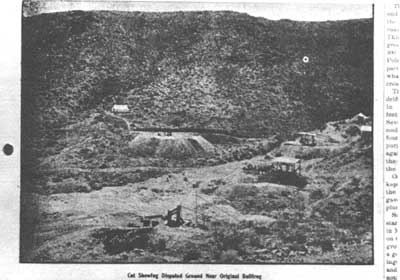

As events were to prove, the organizers of the Apex Company knew about these conflicting boundaries when the North Bullfrog claim was filed, but they forged ahead anyway., hoping to capitalize upon a few technical mistakes committed by the other companies.. Work on the Apex ground started in the fall of 1905, and soon all the competing companies were sinking shafts within a stone's throw of one another. The original Bullfrog shaft was the focal point, with the Apex Company sinking only forty feet away from it, the Bullfrog Extension working on the east, the Bullfrog Fraction on the west, and the West Extension to the west of the Bullfrog Fraction.

|

| Illustration 19. Stock certificate. Courtesy Nevada Historical Society. |

|

| Illustration 20. Advertisement from the Rhyolite Herald, November 10, 1905. |

The development race between these companies continued through the early part of 1906. The Apex encountered encouraging ore values, stock sales were adequate at 114: per share, and the promoters were confident enough of the mine's prospects that they decided to apply for a patent. That, however, was the move which spelled the end of the mine. When the Apex filed its papers for patent, the local newspapers, as required by law, published the legal description of the claim boundaries. When these were published, the West Extension Company immediately realized that the Bullfrog Apex was attempting to patent land which the West Extension had a prior location to, and it filed an adverse action against the Apex application, and then filed for its own patent. [30]

While the patent applications and adverse suits were slowly winding their way through the jurisdiction of the U.S. Land Office at Carson City, both companies continued to sink development shafts and tunnels, trying to find the elusive ore bodies, and determine if there was anything underneath the ground worth fighting for. When the Apex Company uncovered a vein of gold assaying $251 to the ton, the question was settled, and the legal battle intensified. The Bullfrog Extension had by now realized that the Apex patent also infringed upon its ground, and filed a second adverse suite against it. At about this time, the struggle was elevated from the Land Office to the civil court system of Nevada.

Law suits, then as now, took time, and in the meanwhile all the companies involved continued to develop their mines. At the very least, the company which lost the suit hoped to extract the best ore from the ground before the case was ever heard, thus minimizing its losses. By October, the Bullfrog Apex realized that the West Extension was winning this particular race to gut the contested ground, and managed to obtain a writ of claim and delivery, stopping the West Extension from shipping high grade ore from the mine until the suit was settled.

|

| Illustration 21. Photo from the Rhyolite Herald of July 27, 1906, showing the location of the ground in dispute between the Bullfrog Apex, the West Extension, the Bullfrog Extension, and the Bullfrog Fraction. The shaft and windlass at the bottom of the picture are on the property of the Original Bullfrog; immediately above it can be seen the circular dump of the Apex; the right-center workings are on the Bullfrog Fraction; and the right-top workings belong to the West Extension. The ground in dispute between the Apex and the Bullfrog Extension is off to the right, out of the picture. |

When the first hearing of the case took place, in the local Rhyolite court on October 9th, the judge soon realized that the case was too complex for him, and transferred it to the district court at Tonopah. The move meant higher legal costs to all parties involved, but it also meant more time to exploit the mines while awaiting results. But by this time the Apex was running into trouble. The great publicity surrounding the court suit was taking its toll upon the company, for the Apex was a relatively unheralded company, compared to the well-known West Extension and the less famous Bullfrog Extension companies. As a result, the stock of the Apex, which had been selling at a high of 11¢ per share in May of 1906, fell completely off the trading board within a few weeks of the announcement of the legal suits. Strapped for money to proceed with either the development of its prospect or the long legal battle, the Apex took its case to the people, in the form of a long newspaper advertisement. The appeal, however, seemed to have little effect, for Bullfrog Apex stock did not reappear on the market. [31]

As 1906 gave way to 1907, conditions remained much the same. The case slowly ascended the court calendar in Tonopah, and the West Extension, Bullfrog Extension and Bullfrog Apex companies continued to develop their respective portions of the disputed ground. By this time the West Extension Company had increased its stake in the affair, through the purchase of the Bullfrog Fraction ground, which effectively doubled the amount of land at dispute between it and the Apex. On February 8th, the case was finally heard in the district court at Tonopah, and the opposing factions were given another thirty days to file final briefs.

Finally, during the first week of May, the Tonopah court rendered its judgement. The ground known as the Delaware claim of the West Extension, and that known as the Bullfrog Fraction, the court announced, had been located and recorded properly prior to the location of the North Bullfrog claim of the Bullfrog Apex Company. Thus, despite the contentions of the Apex attorneys that the former claims had been allowed to relapse, the court found that such was not the case, and ruled entirely in the favor of the West Extension and Bullfrog Extension companies. The West Extension gleefully placed a full page ad in the Bullfrog Miner,, announcing that title to its ground was now uncontested. The Bullfrog Apex was left in the cold--its claim to the North Bullfrog ground was completely invalidated.

Although the Apex Company owned other property, such as seven claims near the Happy Hooligan, six miles to the west of the Original Bullfrog, the company had exhausted its treasury through its hectic development of the North Bullfrog claim, and through the legal costs of the court suit. Now, with no more money to pursue further mining, and with the utter loss of public confidence prohibiting the sale of further stock, the Bullfrog Apex Mining and Milling Company quietly closed its doors and went out of business. The company had taken a calculated gamble and had lost. [32]

e. Original Bullfrog Extension

On April 13, 1905, a group of five hopeful promoters incorporated yet another Bullfrog mine, this one called the Original Bullfrog Extension Mining Company--not to be confused (except perhaps by investors) with the Original Bullfrog or with the Bullfrog Extension. The Original Bullfrog Extension was the owner of two claims called the Hillside and Hillside #1, which were situated directly north of the Delaware claim of the West Extension Company arid the Delaware 42 claim of the Bullfrog Extension, respectively.

Despite the close similarity of names, the Original Bullfrog Extension was neither an "original" nor a true extension of the Original Bullfrog. That in itself was no great problem, but when potential investors figured out that the Original Extension was separated from the Original Bullfrog by the claim of the West Extension and the Bullfrog Extension, the company failed to attract much interest, and its stock was never placed on the trading boards. Nevertheless, the company went to work, with the forlorn hope that either the rich Bullfrog ledge would dip entirely through the intermediate properties and enter its ground, or that they would have the great luck of finding a separate ledge upon their own ground. By the end of 1905, pursuing these hopes, the Original Bullfrog Extension had sunk a shaft to a. depth of one hundred feet, and had equipped its property with a horse whim for raising the rock. [33]

The company continued its development work through the early part of 1906, but without much luck. Neither the Bullfrog ledge nor any other ledge appeared on its property. Then, in April, the Original Bullfrog Extension temporarily shut down work, while its superintendent traveled to San Francisco to learn the effects of that city's recent disaster upon the company's finances. The mine lay idle throughout the summer, but by September the company had recovered enough to announce that work would soon be started. Soon, however, turned out to be a long time coming, and work did not resume at all that fall. In December, with the property still laying idle, the company gave up the hope of developing the mine on its own, and advertised for a contract to sink fifty feet in the shaft. The advertisement described the company's property as being equipped with a 155-foot deep shaft, a good whim and a blacksmith shop. The company offered to provide the contractors with timbers for the shaft and with tools for mining.

The contract was let, and by March of 1907 had been completed. No ore was found, however, and the Bullfrog Miner was forced to admit that "nothing of importance has thus far developed" at the Original Bullfrog Extension. Nevertheless, the company continued to work through April, before finally giving up hope. Throughout the rest of 1907 and most of 1908 the property was dormant, with only the minimal necessary annual assessment work being done. In 1909, however, even the assessment work was not done, which meant that the Original Bullfrog Extension Company relinquished title to its claims. Another Bullfrog mine had died. [34]

f. Bullfrog Red Mountain--Rhyolite Bullfrog

The Bullfrog Red Mountain Mining Company had even less of a claim to the magic Bullfrog name than any of the above mines, for its four claims were situated almost a mile southwest of the Original Bullfrog. Undaunted, the company was organized early in 1905, and started to work, reporting that they had found ore worth $47 per ton. Despite this claim, efforts to develop the mine were not successful. By the time the Red Mountain had organized, approximately seventy-five other companies in the district had already used the Bullfrog name, with a noticeable cheapening of its value in attracting investors. This, along with the remote location of the mine, made it evident to any half-way careful speculator that the Red Mountain outfit had absolutely no hope of cashing in on the Original Bullfrog ledge, and just as remote a chance of finding another ledge of its own. As a result, although the Bullfrog Red Mountain announced the usual incorporation of 1,000,000 shares worth $1 each, the stock never hit the trading boards.

Before the company had really got work off the ground, the San Francisco disaster cut off operations. The mine was idle through the rest of 1906, even though it did take the public relations step of announcing that Sam Newell, superintendent' of the Original Bullfrog, had also been appointed as superintendent of the Red Mountain. Unfortunately, Newell had nothing to supervise, and nothing happened.

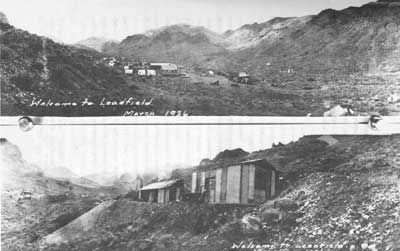

Then, in early 1907, the mine was sold to a new group of promoters, and the cycle started all over again. The new owners, led by two men named Voorhees and Taylor, decided to reincorporate and change the mine's name, hoping thus to sever all connections in the investors' minds with the losing predecessor. Since Voorhees and Taylor were two of Rhyolite's leading stock promoters and brokers, the new company had all the benefit of their experience and connections. From January to April, the Rhyolite newspapers carried weekly descriptions of the reorganized mine, thus keeping it in the public's mind, even though no work was being done. Finally, on April 6th, the new company incorporated itself as the Rhyolite-Bullfrog Mining Company, capitalized as usual for $1,000,000 and with the grand total of $1,003 in the treasury. [35]

With a newly incorporated company and with money in the treasury, the Rhyolite-Bullfrog Company underwent a flurry of development work. Camp buildings were completed in early October, including a boarding house, stables, blacksmith shop and a superintendent's office. Sinking was resumed by three shifts of miners, $10 ore was reported, and the company cleverly circulated the rumor through the newspapers that it had a good treasury reserve, in an attempt to bolster investor confidence. The papers were full of encouraging news carefully planted by the skillful[ stock brokers running the company. During the fall and winter of 1907 reports of $23 ore, "solid values", "promising" finds, and surface showings "the best in the district" appeared almost weekly. Then, suddenly, with the end of 1907, all work ceased. Despite all the promotional gimmicks, the mine was not attracting investors.

Through the entire years of 1908 and 1909, little work was done at the Rhyolite-Bullfrog, even though the company did display ore samples at the American Mining Congress convention in Goldfield in the fall of 1909--another good promotional stunt. That was the company's last gasp, however, and the mine lay idle through 1910 and 1911. Finally, in March of that year, the company's four claims were sold at auction by the Nye County sheriff, under a writ of execution brought by two disgruntled stockholders who wished to recover their ill-spent funds. The two men received title, to the mine for their efforts, and even tried a little prospecting work on their own, but the Rhyolite-Bullfrog, nee the Bullfrog Red Mountain, soon died an untroubled death. The venture had proved once again that even the very best of promotional campaigns could not save a mine which had no ore. [36]

Such were the varied fortunes of those who tried to find success in the shadow of the Original Bullfrog strike. As noted before, the above mines were the more honest of the many which carried the Bullfrog name, for they at least tried to find ore on 'their grounds. In this sense, they gave their investors a better run for their money than did the promoters who merely took stockholder's funds and ran. In the end, however, all came out equal, for no one made any money, and some merely lost it more quickly than others.

Had things, been different--had the Original Bullfrog been another Comstock--these surrounding mines could have made fortunes. That was what the promoters and stockholders had' bet upon, but as the twists of fate and geologic formations would have it, the Original Bullfrog itself turned out to be a low-grade proposition, despite the early finds of rich pockets of gold, and the surrounding mines found no ore at all. The early demise of the Original Bullfrog thus spelled doom for all the neighboring tadpoles, but such is the nature of the mining game. You pay your money and take your chances. The story of these mines is important, though, for they are typical tales which are repeated again and again in all the camps of the western mining frontier.

g. Present Status Evaluation and Recommendations

Due to the limited nature of the activities which took place on the property of these various mines, comparatively few structures were ever erected. Only a few of the mines had hoists or gallows frames, as most did not pass the windlass or whim methods of raising ore. Likewise, most of the mines never employed enough miners to warrant the construction of boarding houses or similar buildings. And, since all these mines failed before the general exodus of the Bullfrog district took place, the few improvements and structures located at their sites were immediately salvaged for use elsewhere, in the time-honored manner of desert mining, where wood was always a scarce commodity.

As a result, there are no structural remains at any of these mines. The only clues to past activities are the numerous pits, prospect holes, adits, and shafts which dot the landscape around the Original Bullfrog. The limited remains of these limited mining efforts are not of National Register significance.

Interpretive signs, which would point out the location of these mines, and briefly tell the story of their vain attempts to cash in on the Bullfrog bonanza, would be of historical interest and educational value to the visitor. Unfortunately, in the history of man's efforts to extract wealth from the earth, the failures of small-scale mines such as these are far more typical than is the small percentage of mines which actually made money.

|

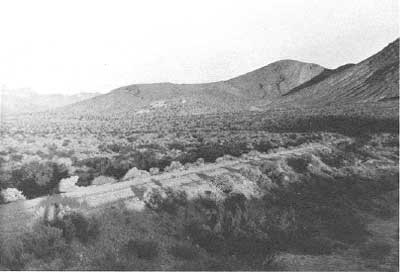

| Illustration 22. Dumps of the Bullfrog Extension Mine, looking southeast from the Original Bullfrog, may bee seen in the center and left-center of the picture. These lonely scars are typical of the only clues remaining to tell the story of feverish attempts to cash in on the glory of the Bullfrog bonanza. 1978 photo by John Latschar. |

4. Bullfrog West Extension Mine

a. History

While Shorty Harris was drinking in Goldfield in celebration of the discovery of the Original Bullfrog mine, he met an old acquaintance named Len P. McGarry. McGarry had been born in Eureka, Nevada, and had spent his entire life in the mining state, cutting his eye teeth on the rushes to Tonopah and Goldfield. He was the sort whom the local newspapers described as a "young man of promise," but his promises had temporarily run out, and he was looking for new fields of action. Quickly realizing the potential of the Bullfrog strike, McGarry reestablished his friendship with Shorty, and accompanied him back to the scene of the strike. There, on August 26, 1904, McGarry staked out some claims to the immediate west and north of the Original Bullfrog.

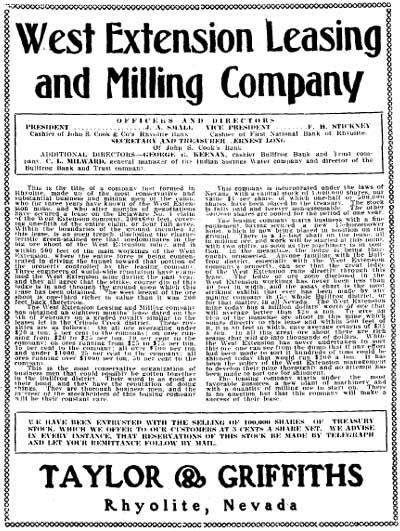

For a while, McGarry became sidetracked from mining, as he was one of the first investors and promotors of the Bullfrog townsite. His claims were recorded, but were not worked for over a year. But when the Original Bullfrog Mine started shipping its pockets of high-grade ore in 1905, McGarry regained interest in his claims, and went looking for financial backers. By December his search was successful, and on the 7th of that month the Bullfrog West Extension Mining Company was incorporated, with McGarry as president. Although the incorporation was very typical on paper, with 1,000,000 shares of stock listed at a par value of $1 each, the company decided to retain the majority of the stock, and sold a mere 125,000 shares, at 12-1/2¢ each, in order to raise the initial development fund. Stock sales were brisk, due to the location of the company next to the Original Bullfrog, and the West Extension was soon ready to begin work. [37]

|

| Illustration 23. Advertisement from the Rhyolite Herald, October 27, 1905. |

From the very beginning, the West Extension had better chances of intercepting the Bullfrog ledge upon its property than any of the other Bullfrog tadpoles, simply because it was the last to begin active operations. By the first of 1906, most of the mines surrounding the Original Bullfrog were showing signs of failure, and the Original itself had lost the rich ore ledge which had stimulated the first glory days. By process of elimination, this meant that if the Bullfrog, ledge went anywhere, it had to go through the West Extension property. The company followed this philosophy, and began sinking its shaft at the likeliest point.

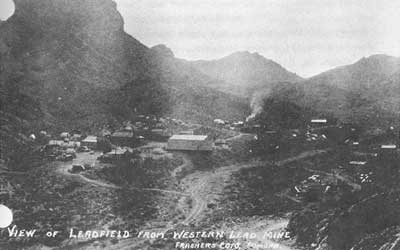

By May of 1906, after only a few months of exploration work, the West Extension seemed to discover the first signs of the Bullfrog ledge, and the local newspapers duly reported the presence of "fine ore" in the company's shaft. Unfortunately, this was, the exact time at which the West Extension discovered that the Bullfrog Apex was encroaching upon its ground, and the long and costly legal struggle, described above, began. Nevertheless, the West Extension carried on, and began taking out high-grade ore, worth up to $200 per ton, to be sacked for, future shipment.

Within a few months, the early indications seemed proven, and in July the company's directors decided to withdraw the stock from the trading market, in order to capitalize upon the future profits of the mine themselves. With the mine reporting ledges averaging $50 per ton, with some rich pockets running as., high as $2,670, the decision seemed fully justified. For another two months the company explored, results continued to be encouraging, and in September the decision was made to shift from exploratory mining to development on a larger scale. A $5,000 hoisting plant was ordered, consisting of a 25-horsepower Fairbanks-Morse engine, a four-drill capacity air compressor, and accessories. Len P. McGarry, who was acting as superintendent of the mine, as well as president of the company, increased the work force to ten miners. In answer to inquiries from eager investors, the company announced that it had ample funds to pay for the escalated development plans, thank you, and that none of the company's stock would be offered for sale.

Despite the continuing annoyance of the law suit versus the Bullfrog Apex, which among other things prevented the West Extension from adding to its treasury by shipping the high-grade ore, the company forged ahead. The big new hoisting plant arrived in late October and was soon installed and working. The Bullfrog Fraction claim was purchased and the West Extension Annex company was formed to exploit it. By this time the growing West Extension complex looked so strong to local and state investors that when the company announced that it would sell 150,000 shares of the Annex stock at 15¢ each, over 50,000, shares were purchased in two weeks--despite that fact that 15¢ per share was an exorbitant price for stock in a company that had not yet commenced mining. As 1906 came to an end, the West Extension looked like one of the best properties in the Bullfrog district, even though title to some of its land was still a matter of dispute. [38]

The mine continued to prosper in early 1907. Another shoot of rich ore, assaying up to $900 per ton, was opened in January, and more encouraging discoveries were made the following month. The Bullfrog Miner, after describing the latest strike in its February 22d issue, concluded that even though the "West Extension is only a baby as yet," it was. "unquestionably" the "finest piece of goods" in the district.