|

El Malpais

In the Land of Frozen Fires: A History of Occupation in El Malpais Country |

|

Chapter VII:

ECONOMIC DIVERSITY AND EXPANSION

If anybody could eke out a living in the malpais, it was Simon Bibo. A Frenchman of Jewish faith, Bibo and his brothers and sisters emigrated to New Mexico after the Civil War. [1] Possessing a sharp business mind, Simon entered the mercantile trade, operating a trading post at Cebolleta. Purchasing or trading for corn from the surrounding ranchers, Bibo, in turn, hauled the produce by wagons across the malpais, passed the ice caves at Bandera Crater, to Fort Apache, Arizona. For a brief period, Simon occupied the position of post trader at Fort Apache. In 1871, he returned to Cebolleta where he engaged in cattle ranching and expansion of his business enterprises, which included satellite stores at Cubero, Laguna, San Rafael, Moquino, and Bibo. [2] The visionary Bibo perceived the economic benefits that the railroad offered with its station at Grant. He jumped at the opportunity to open another trading post. Simon became Grant's second postmaster in 1883, a position he maintained intermittently for 22 years. In 1912, Bibo served in New Mexico's first State legislature. [3]

Bibo's economic opportunities were a direct result of the railroad, which developed the sheep and cattle industry. With the advent of the railroad, ranchers had a means of transporting their livestock to market. Moreover, the railroad encouraged the ranchers to expand their herds. New Mexico's sheep census skyrocketed following the subjugation of the Indians and the coming of the railroad. No longer did Navajo, Ute, or Apache raiders devastate the surrounding flocks. Settlers expanded their herds without fear of livestock loss. In 1870, the New Mexico sheep count numbered 619,000 animals statewide. Ten years later the sheep population exploded to 3.9 million. According to the New Mexico census taken in 1885, ten thousand sheep alone belonged to San Rafael residents, Martin Gallegos and E.Q. Chavez. [4]

San Rafael rapidly became the center for sheep raising. Sheep ranchers acquired or controlled vast grazing empires blanketing an area south of the chain of craters and continuing eastward to the Acoma Reservation. The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company, in a bid to remain solvent, began the process of selling off its vast land grants in Arizona and New Mexico. Jose Leon Telles, Manuel Padilla Y Chavez, Monico Mirabal, and Romulo Barela carved out huge holdings in the San Rafael Valley. Monico Mirabal and his son Don Sylvestre Mirabal, took advantage of the railroad's desire to liquidate its assets in the region. Monico purchased or leased over 250,000 acres of land, with property holdings extending south of Bandera Crater. [5]

In managing their sheep, large landowners leased out herds under a Spanish term "partidos." "Partidos" represented the lessee who agreed to supervise the wandering herds. After a specified time period, the lessee returned to the owner his original herd plus a percentage, with the lessee retaining possession of the remainder. The "partidos" system allowed small landowners with little capital to establish their own herds. Sheepherders known as Basques, derived from the herders of the Spanish-French borderlands along the Pyrenes Mountains, watched over the "partidas," numbering fifteen hundred to two thousand animals. [6] Traditionally, two Basques superintended the needs of the "partidas."

At the height of the sheep industry, 1880 to 1925, scores of sheep camps dotted and circumvented the malpais terrain. A solitary existence marked the life of the Basque herder. In order to provide enough pasturage, Basques moved their flocks every 3-4 days. A typical herd of ten thousand to twelve thousand required grazing land equivalent to three townships or an area 18 miles long and 18 miles wide. Basques lived with the sheep all year, sleeping in a tent in the winter. A fire in front of the flapless tent provided the only source of heat and means of preparing warm meals. In June sheepshearers invaded the camp on the heels of the May lambing season. Depending on the skills of the individual shearer, 80 to 110 sheep were sheared daily by each person. Each sheep yielded on average four pounds of clipped wool. Packed into 200-pound bags and placed on a waiting wagon with about seven other bags, the wool bounced along the malpais to a destination point, usually Grant because of its location on the railroad. [7]

Coinciding with the development of sheep ranching around the malpais, the cattle industry took root. For ethnic and economic reasons, its growth lagged far behind the more established sheep business. Statistics for Valencia County in 1885 reflected the disparity. Countywide, sheep outnumbered cattle 157,400 to 16,526. In the community of San Rafael, sheep held the upperhand 10,000 to 820. [8] Statewide, the 1880 cattle census depicted 347,936 cattle, pale in comparison to the 3.9 million sheep on New Mexico's range lands. Toward the end of the decade cattle companies began to make inroads into the region. In 1887, the Arizona Cattle Company, whose primary investors constituted officers from Fort Wingate, purchased 121,490.65 acres at $1.00 per acre from the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. Much of the land lay west and south of the malpais. [9] Another local ranching outfit, the Cebolla Cattle Company acquired 41,592.19 acres east of the malpais at 50 cents per acre. [10] Six miles east of Grant, on June 25, 1884, the Acoma Land & Cattle Company became incorporated. This Missouri-based company with offices in Albuquerque, controlled thousand of acres east of the malpais. [11] Ten miles west of Grant at the new village of Bluewater, the Zuni Mountain Cattle Company began operations in 1892. [12]

Both the cattle and sheep industries expanded their presence in the area until smittened with a series of natural and human disasters that forced them to trim back their ambitious plans. Severe droughts plagued New Mexico between 1891 and 1893. [13] The Panic of 1893 reverberated through New Mexico with the region feeling the aftershocks until 1897. To make matters worse, the depletion of the range lands from overuse hampered progress, giving clear warning that the land did not guarantee unlimited and unrestricted use. [14]

Another industry began to strike an economic cord in the malpais vicinity in the 1890s--timber. Timber from the Zuni Mountains went into the construction of Fort Wingate at Ojo del Gallo. The interest in timber continued with the advance of the A&P Railroad in 1881. The abundance of forested lands on the Zuni Mountains achieved significance because no other sources of lumber lay adjacent to the railroad's route. The A&P awarded J.M. Latta the contract for providing the railroad with ties. Latta sub-contracted with John W. Young for the production of a half-million ties, a quantity sufficient to produce 200 miles of track. At Bacon Springs on the continental divide, Young established headquarters for his tie-cutting camp, conveniently located near the railroad depot at Crane's Station. In 1882, Crane's Station became Coolidge, named for railroad executive, Thomas Jefferson Coolidge. In 1898, Coolidge became Dewey, and by 1900, Dewey was dropped in favor of Guam. Later the town was changed to Perea before locals ultimately settled on Coolidge. [15] Lumber operations flourished south of Coolidge in the 1880s. At one point, the area supported three sawmills. [16]

On June 30, 1890, William W. and Austin W. Mitchell of Cadillac, Michigan, purchased 314,668.37 acres of forested land in the Zuni Mountains from the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. The Mitchell Brothers inspected their reserve in May 1891 to select sawmill and planing mill sites. On the same visit they investigated the feasibility of laying tracks from their mill, deep in the Zuni Mountains to the A&P rails. Convinced of the practicality of their idea, the brothers entered negotiations with A&P executives, culminating in an agreement whereby the railroad would construct the spur line in exchange for monetary considerations. The railroad appropriately enough became known as the Zuni Mountain Railway. [17]

By early 1892, the new townsite of Mitchell, 30 miles west of Grant's Station, began to take form. One hundred and fifty people initially set up residence. Mitchell supplied more amenities in terms of general merchandise stores, restaurants, cafes, and medical offices than towns of much larger stature. The economic outlook did, indeed, appear bright. Mitchell Brothers' contract with the A&P Railroad to saw and deliver 12 million feet of lumber per annum lured the Mitchell citizenry into a sense of false security. [18]

In May, the narrow-gauge locomotive arrived. Construction of the Zuni Mountain Railway clipped along at a rapid pace of one-half mile per day. A month later the sawmill began cutting lumber. Work production had barely started when disaster befell the enterprise. The one and only locomotive derailed in the woods, causing a shutdown until a replacement engine could be built and transported to the logging site. The new locomotive arrived in late August and logging resumed. A month latter Mitchell Brothers closed operations for good. Reasons for the closure suggest the brothers became despondent over the sick economy (Panic of 1893) and irreconcilable differences with A&P concerning freight rates. Mitchell Brothers conveyed back to A&P 22,565.08 acres but retained clear title to more than 292,000 acres. [19]

The demise of Mitchell Brothers shocked and crippled the town of Mitchell, too. Shaken to its knees, it fought to survive. In 1896, artifacts excavated from Pueblo Bonito Ruins at Chaco Canyon by the Hyde Exploring Expedition were housed in Mitchell. The company built three warehouses and in the process saved Mitchell from ghost-town status. Hyde erected a store in Mitchell to handle its lucrative business dealings in Navajo rugs and jewelry. They succeeded in re-naming the community Thoreau, after the philosopher, Henry David Thoreau. [20]

In 1903, when the Albuquerque firm, American Lumber Company, acquired Mitchell Brothers' 292,000 acres, it resurrected the timber industry at Thoreau. American Lumber formed a business partnership with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, formerly the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, and the Frisco had plunged into receivership following the Panic of 1893. Under reorganization the A&P became part of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. [21]

Because of better management, the American Lumber Company thrived for a decade. At its height of operation, about 1910, the firm sawed 60 million board feet of timber at its Albuquerque sawmill. In other years the firm averaged 35 million board feet. Approximately 1,500 persons were on its payroll, 700 of them employed as cutters in the Zuni Mountains south of Thoreau. [22] Logs were hauled over the Zuni Mountain Railway, which included 55 miles of primary track and additional spur lines. At Thoreau, the cut logs were stacked on flatcars and shipped to the planing and sawmill plant in Albuquerque. An average of 100 carloads of timber rumbled eastward from Thoreau bound for Albuquerque daily. [23]

Logging revitalized Thoreau and produced a rippling effect that created other temporary boomtowns. Deep in the forests of the Zuni Mountains, headquarters were established for the logging operation at Kettner, named for the local homesteader. Kettner claimed a round-house and a two-story hotel with 50 rooms. Nearby a "cookhouse" accommodated upwards to 700 hungry lumberjacks at one sitting. [24] Kettner's death evolved almost as fast as its birth. When logging operations transferred to Sawyer a few miles distance, Kettner folded. Like its predecessor, Sawyer spawned a reputation as a rough-and-ready town. When the timber cuttings moved on to virgin tracts, Sawyer, too faded into oblivion.

The American Lumber Company remained active until September 1913, when it suddenly halted all operations. Defaulting on its mortgage bonds, the company fell into receivership. In 1917, through a labyrinth of corporate maneuvers the tangible assets of American Lumber eventually became the property of the McKinley Land and Lumber Company, who, in turn, was owned by the West Virginia Timber Company. [25] McKinley Land and Lumber Company rekindled logging operations in the Zuni Mountains until its absorption by West Virginia Timber Company president, George E. Breece, in 1924. [26]

Besides the permanent establishments of Thoreau and Grant, the community of Bluewater emerged, fastened to the umbilical cord of the railroad. In 1881, Bluewater, located 10 miles west of Grant, was founded. To encourage settlement, lurid advertisements appeared in newspapers soliciting settlers to homestead in the region. Two people who responded to the call were A.E. Tietjen and F.P. Nielsen. Both bore affiliation with the Mormon Church and envisioned the church's expansion beyond the boundaries of Ramah. Tietjen and Nielsen inspected Bluewater and proposed to Church elders that Bluewater and Cotton creeks should be damed. They argued that if enough water could be impounded the area could sustain agricultural pursuits.

In 1894, the Mormon Church nodded in acquiescence to the plan, leading to the development of the Bluewater Land and Development Company. The company purchased land from the railroad and built their townsite three miles from Bluewater Station. Nine miles west Mormons erected an earthen dam to impound the waters of Bluewater and Cotton creeks. [27] The dam broke in 1900 but was quickly rebuilt. Torrents of rain washed it out again in 1904, 1906, and 1909. [28] Despite the calamities, the Mormon colony persevered.

Economic expansion and a moderate growth rate notwithstanding, the malpais region at the turn of the century still reflected some of the charm, certainly the reputation, as a holdover of the Wild West. Railroad workers, cowboys, sheep ranchers, sodbusters, and lumberjacks formed an unlikely melting pot. Fisticuffs, stabbings, shootings, drunken rowdies, and train robberies occurred frequently. On June 20, 1889, a brawl broke out at the Block and Bibo Store in Grant, following a spree of drinking by fun-seeking cowboys from the nearby Acoma Land and Cattle Company spread. Bartender Sol Block refused to serve beer to the drunken cowboys, which precipitated the fight. Simon Bibo, Block's business partner and a deputy sheriff, came to his friend's assistance. In the melee, Block picked up a revolver from the barroom floor and began shooting. When the smoke cleared, one cowpuncher lay dead, another seriously wounded. Block and Bibo emerged from the encounter with bruises and bloody faces. Fearing reprisals from revengeful cowboys, armed guards were posted around the darkened town and the saloon. San Rafael Justice of the Peace, Casimiro Lucero, acquitted Block and Bibo of murder charges on grounds of self-defense. [29]

|

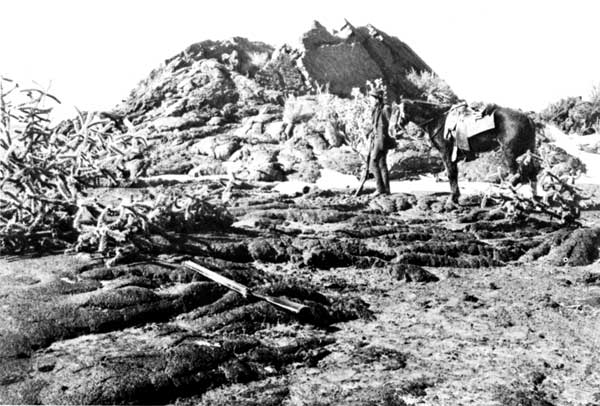

| Figure 4. In the lava beds near McCartys, circa 1885. Photo by Ben Wittick, Courtesy School of American Research, Collections in the Museum of New Mexico, Neg. No. 16475. |

In November 1897, the last train robbery of the Santa Fe Railroad occurred near the malpais. While accounts differ, the perpetrators apparently belonged to the Black Jack Christian gang. Gang members boarded the eastbound train either before or at Grant's Station. About six miles east of Grant, the outlaws disengaged the baggage cars from the locomotive and express car. Using explosives, they blew apart the safe discovering $100,000 in gold and currency. The bandits headed south toward the malpais hoping to lose any would-be trackers in the gnarled lava beds. While some of the outlaws were apprehended, the whereabouts of the gold remained elusive giving rise to speculation that it is still hidden in the malpais. [30]

Accounts of buried gold in the malpais persist. The most notorious version of malpais gold is the chronicle of the "Lost Adams Diggings." According to local legends, freighter J.J. Adams had accompanied a party of miners into the malpais in 1864, to search for gold. The group discovered gold but in the process began to run low on provisions. Adams went to Fort Wingate to obtain supplies. On his return, he found all of his companions killed except for one by a band of Apaches. The two men buried the gold and managed to escape the wrath of the Apaches. Adams and his wounded friend, John Brewer, finally reached the sanctuary of Fort Apache, Arizona. While at Fort Apache, Adams allegedly shot an Indian in a dispute over a horse. Imprisoned, he was unable to return to the malpais to reclaim the gold. When Adams reappeared in the malpais some 20 years later, he failed to locate the site. Years of wandering over the rugged lava terrain yielded nothing and Adams left in frustration but not without implanting the seeds of gold legends in the malpais. [31]

|

| Figure 5. In the lava beds of New Mexico, the rough, jumbled lava made a haven for outlaws and spawned luried accounts of gold buried in the malpais. Photo by W. Cal Brown, Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Neg. No. 66552. |

At the closing of the final quarter-century of the 1800s, the malpais region reflected remarkable economic and sociological adjustments. The Navajos no longer held dominion over the country, in their stead advanced sheepmen and cattle ranchers. Along the ridges and valleys of the Zuni Mountains, timbermen emerged and tapped into what seemed to them an unlimited resource.

Moreover, dugouts and rough-poled cabins punctuated the landscape. Bean fields and chicken coops, dams and dikes had supplanted a sagebrush environment. Towns like San Rafael, Grant's Station, Thoreau, and Bluewater were survivors in the never-ending cycle of boom or bust. But without the advancement of the railroad none of the changes could have taken place easily. The end of the first quarter-century of the twentieth century still found the area tethered to the railroad's umbilical cord for economic dependence.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

elma/history/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2001