|

El Malpais

In the Land of Frozen Fires: A History of Occupation in El Malpais Country |

|

Chapter VIII:

A COUNTRY IN TRANSITION: EL MALPAIS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Not since the railroad had one single event so significantly altered the fortunes of El Malpais as the emergence of timber mogul, George E. Breece. Breece, the new owner of the McKinley Land and Lumber Company activities near Thoreau, reorganized the company and named it for himself, the George E. Breece Lumber Company. Breece continued logging operations south of Thoreau, shipping 30 million board feet annually. [1] But the pragmatic Breece realized that 25 years of intense timber-cutting left the forests depleted. In order to profit from his heavy investment, Breece decided to shift timber harvests from Thoreau to the untapped belt of forests comprising the Zuni Mountains southwest of Grant. On the west side of Grant Breece constructed a roundhouse, now the site of Diamond G Hardware, and homes to support his army of laborers that swelled the town and the countryside with 4,000 new residents. [2]

To reach the virgin forests, Breece constructed tracks westward from his roundhouse. Begun in 1926, the route of the Breece Railroad traversed the malpais southwest of Grant ascending Zuni Canyon and continued to Malpais Springs, Paxton Springs, and Aqua Fria Springs--a distance of 20 miles. Upon completion of all the spur lines, 38 miles of track network laced through the southern Zunis. The dismantling of the defunct Zuni Mountain Railway south of Thoreau provided some of the track. [3] By early 1927, timbermen invaded the depths of the forests and began felling trees. Breece endeavored to make his mammoth enterprise efficient. Whenever possible he utilized trucks to haul the wood to the main line railroad, thereby becoming less dependent on the railroad. [4]

Breece Lumber Company guaranteed immediate prosperity for Grant and San Rafael. New businesses exploded on the scene, and old ones enlarged in order to provide services for new customers. Schools, churches, and community buildings sprang up. In 1929, Grant boasted a high school, one of the few in the huge expanse of western Valencia County. The Grant Review, a weekly newspaper published in Gallup and bused to Grant, provided local news and commentary. Running water and electric lights embraced Grant in 1929, catapulting the booming settlement into mainstream America. [5]

While Grant basked in the glow of its success, neighbors to the west in Bluewater, also improved their economic status. The Mormon colony erected a permanent concrete dam to replace their antiquated and troublesome earthen dam. The Santa Fe Railway became interested in the project partly because the porous relic often broke and washed out sections of Santa Fe track. Captain W. C. Reid, attorney for the railroad, spurred efforts for the construction of the Bluewater Irrigation Reservoir and the Bluewater Dam. The final completion of the dam produced immediate results for it converted 6,000 acres of arid wasteland into tillable, irrigated croplands. [6]

Prior to the coming of Breece Lumber, the quantity of homesteaders was a trickle. To encourage settlement, Congress passed in 1916, the "Stock Raising Homestead Act," which permitted homesteaders to homestead the public domain. The 1916 Homestead Act stipulated that individual persons could acquire a section of land upon payment of a $34 "filing fee." To retain the property the homesteader had to remain on the land for seven months out of the year for a period of three years. In addition to living on the land, the homesteader agreed to build a "habitable" home and show evidence of $800 worth of improvements, usually taking the form of fence lines or putting so many acres of lands into production. At the expiration of three years the settler paid a "proving fee" and took official possession of his property. [7] To assist the returning veterans of World War I, the government allowed them to establish ownership after only six months. [8]

With the development of the thriving timber industry at Grant, the number of homesteads on the perimeter of the malpais increased steadily, particularly during the Depression Era. The east side of the malpais became dotted with new arrivals. Most immigrants originated from Texas and Oklahoma. Nearly all were poor. Homes were constructed from long timbers, if available, otherwise a poled house or dugouts sufficed. The poled house was fashioned by setting into the ground four corner posts with a long pole forming the roof. Shorter poles set vertically framed the structure. Windows and doors were fashioned from cutting away portions of the vertical poles. Cabins normally contained two rooms separated into sleeping and eating compartments. A log wall or cloth curtain sometimes partitioned the rooms. Roofs and floors consisted of packed dirt. In some instances homesteaders built rock houses. The eastside of the malpais contained an unlimited supply of rock debris, representing the ruined foundations of prehistoric Indian homes who had initially settled in the area. Resourceful settlers loaded their wagons with rocks and carted them home for use in erecting their own structures. [9]

A hardscrabble existence marked the life of the homesteader. Lack of water defeated most attempts to foster a living from dryland farming. Amenities like schools, churches, and electricity--the latter a creature comfort unavailable in the rural malpais until the 1950s--produced a lasting, negative influence on homesteading. Beans, corn, and vegetables together with chickens, hogs, and beef represented the normal extent of their daily fare. If any food surplus existed, the profits were reinvested in necessary staples such as coffee, flour, and sugar. Yet, the homesteader was not self-sufficient. Often they worked for the larger ranchers, the big timber companies, sold firewood, or sought seasonal employment to make ends meet. [10] Homesteaders took jobs with the Civilian Conservation Corps under the Work Program Administration in the 1930s. Lewis Bright, who homesteaded on the west side of the malpais near the commercial ice caves, found employment with the CCC, helping install culverts along New Mexico Highway 174 (present New Mexico 53), which runs through the malpais from Grants to Zuni. [11] Bright and other locals improved and graded the road. Cinders from nearby cinder cones comprised the road base. [12] Construction of State Highway 174 occurred in the summer of 1938, connecting with State Highway 53 about 14 miles east of El Morro National Monument. [13] Most homesteaders did not last three years. Primitive living conditions, low wages, and the Depression of the 1930s forced them to abandon their homesteads and follow the road to better paying jobs. They left behind their cabins, poignant reminders to those that followed in their footsteps, that life can be bitter and the malpais landscape, unrelenting and unforgiving.

The ebb and flow economics of the livestock growers seemed inconsequential compared to the incessant challenges confronting the homesteaders. Surviving sheepmen and cattle ranchers who escaped the financial debacle of the Panic of 1893 plunged into the twentieth century riding the crest of prosperity. Demand for wool and beef increased through the end of World War I. But the rancher's nemesis, drought, reappeared in 1918 and resulted in decreased production. [14] In 1919, the stock market plummeted, and malpais stockmen witnessed falling prices. To make matters worse for the cattlemen, an epidemic of scabies infected the cattle causing widespread problems. [15] Between 1927 and 1929 sheep prices dipped, while the expense of feeding the animals skyrocketed. In Valencia County, where it had cost twenty-five cents to maintain each head of sheep in 1890 had by 1927 escalated to $4.13. The maintenance expense for sheep, coupled with low wages, forced many of the smaller ranchers out of the business during the 1920s and 1930s. [16]

San Rafael wool baron, Don Sylvestre Mirabal, survived the economic adversity, partly because of his huge land holdings. Shrewd, hard-working, and thrifty, Mirabal built an empire on sheep. Reportedly, the largest landowner in New Mexico, Mirabal owned or controlled land south of San Rafael and west into the Zuni Mountains. Mirabal purchased much of the land at a fraction of its value. Malpais homesteaders often entered into "partidos" agreements with Mirabal, using their homesteads as collateral. If the settler defaulted, Mirabal took title to their land. [17] Despite his enormous wealth, Mirabal remained unaffected by success. His workers described him as a penny-pinching, pot-bellied man, whose habiliments usually consisted of a "worn-out pair of bib overalls, an old hat someone else had thrown away, and, in the winter time, a ragged serape." [18] His workers considered him a kind person but a crafty businessman. Mirabal's death in 1939 terminated large-scaled sheep ranching in the malpais. Cattle became kingpin. The Mirabal estate, an impressive white, two-story, rock house still towers over San Rafael, a fitting tribute to the Mirabals and a symbolism to the four-century dominance when sheep ruled New Mexico.

|

| Figure 6. Sheep camp at Cerro de la Bandera about 1920s. Sheep remained kingpin in el malpais economics until supplanted by cattle. Photography taken by W.T. Lee. Credit U.S. Geological Survey. Photographic Library, Denver, Co. |

Timber, that bastion of erratic employment in the region for 40 years, fell on hard times during the Depression. In 1929-30, Breece Lumber Company experienced a soft market, compelling the firm to layoff workers and induce brief work stoppages in order to remain solvent. The economy did not improve. Breece resorted to frequent work halts and imposed a 20% decrease in wages to keep from going under. By 1931, Breece Lumber Company only employed about 300 timberman in the woods south of Grant. By 1932, Breece decided it might be more profitable to lease his operation.

Grant businessmen, M. R. Prestridge and Carl Seligman, co-owners of the Bernalillo Mercantile Company with stores in Bernalillo and Grant leased the timber operations from Breece Lumber Company. Prestridge and Seligman endeavored to modernize Breece's antiquated rolling stock by purchasing several locomotives, but whenever possible they hauled logs via trucks to the railroad. In 1934, Prestridge and Seligman worked the forests around Paxton Springs, a small community located a few miles northwest of the Ice Caves, which employed approximately 100 men. Undeterred by a sluggish economy, the owners expanded operations by building tracks from Agua Fria to Rivera Canyon. Logging camps pursued the path of the railroad in the Zunis. The logging railroad advanced southwest toward Tinaja. By 1941, however, Prestridge and Seligman could not sustain operations on a profitable basis. They terminated logging from Grants (the town had changed its name from Grant to Grants in 1935) selling back to Breece Lumber Company its rolling stock. Breece did not reopen its Grants facilities. By the summer of 1942, it also closed its giant sawmill in Albuquerque. [19]

The pullout of Prestridge and Seligman was followed by one other bid to keep the timber industry big time in Grants. In 1946, Prestridge Brothers, Bill and Red, contracted with the New Mexico Timber Company to haul timber from Mount Taylor. Lumbering activities around Mount Taylor had been active since the 1930s. The Prestridges remained in business for about four years then suspended operations. Large commercial timber operations in the malpais region went the way of the sheep industry. [20]

With timber and sheep hit hard, malpais residents turned toward agriculture and mining as a means of economic support. A decade after the construction of the Bluewater Dam, Mormon farmers began to exhibit the profitability and suitability of raising crops on a grandiose scale. In 1939, businessmen Ralph Card and Dean Stanley purchased 400 acres of land near Bluewater. They initiated an experimental farm to test the adaptability of lettuce, cauliflower, broccoli, carrots, cabbage, potatoes, onions, and peas to New Mexico's climate. [21] The pilot program proved successful, propelling the Rio San Jose Valley from Grants to Bluewater into an economic upsurge. Carrots became the chief cash crop. In their best years, 2,000 acres of leafy-topped carrots under brand names like "Sky Top" were crated, refrigerated with ice, and placed inside waiting Santa Fe Railway boxcars. Over the course of the carrot season 2,000 boxcars were filled with vegetables. The carloads of produce rolled slowly out of the Grants depot headed for eastern stores with a market value of $2,500,000. [22]

The carrot industry was seasonal, planting in April, and harvesting in late summer and fall. Locals worked in the fields and in the processing plant. Navajos, hired as cheap labor, found jobs primarily in the fields. To provide shelter for the field workers, the companies erected crude huts with indoor plumbing. Initially, the harvesters accepted their pay in script, to be traded at the company commissary. Later the workers received their payment in cash. The carrot enterprise lasted for nearly 20 years. Its death in the late 1950s occurred with the introduction of cellophane bags, which eliminated the demand for leaf carrots. In addition, Bluewater growers could not compete with cheap produce emanating from California. [23]

Prior to the late 1930s, mining activities were marginal in the malpais. In 1916, a small copper mine operated in the Zuni Mountain town of Dierner, supporting 10-20 miners and their families. Unprofitable, the mine shut down in the early 1930s. [24] By the early 1940s, fluorspar and pumice mines developed near Grants. Three fluorspar mines operated by the Navajo Fluorspar Company flanked the west side of the malpais near the commercially operated Ice Caves. Navajo's peak production period occurred during World War II, putting 150 families to work. Fluorspar extracted from the mines was transported to Grants where it underwent processing. Much of the mineral's production fell under the auspices of national defense contracts. Fluorspar was utilized in the manufacture and hardening of steel, use in paints and acids. The flurospar mines remained active until 1952, when foreign competition drove down the price of the mineral. [25]

|

| Figure 7. During World War II, fluorspar mines punctuated the Zuni Mountains offering some economic relief to the depressed region following the demise of the timber industry. Fluorspar, a translucent mineral of varying colors, was extracted and sold to satisfy defense contracts. Fluorspar mines were active in the Zunis until the 1950s, until cheap imports undercut domestic prices. Shown here is Fluorspar Mine Number 21, photograph taken about 1948, from the collection of Mrs. Dovey Bright. |

|

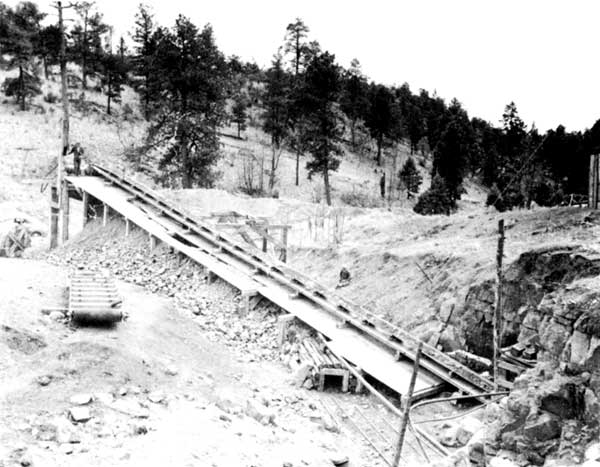

| Figure 8. Fluospar Mine Number 21, showing conveyor belt system. Fluorspar was a multi-purpose mineral used in the manufacturing and hardening of steel, paints and acids. Photograph taken about 1948, from the collection of Mrs. Dovey Bright. |

Pumice, an abrasive substance used for polishing manufactured products, was extracted north of Grants during World War II. The Pumice Corporation of America operated a mine located eight miles north of Grants. In the 1990s, pumice was still extracted north of Grants under the flagship, U.S. Gypsum Corporation. [26]

The mining of coal never became a large enterprise around the malpais. Heavy commercial coal mining interests developed west of the malpais near Gallup. Localized coal mines operated by 2-3 persons normally satisfied all demands and needs for coal.

While pumice and fluorspar assisted the war effort, the lava beds aided the nation's war effort in a different manner. The United States Army at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque began a search in 1942 to locate a practice bombing range. Army personnel gazed toward the malpais as an appropriate site. Under Public Land Order No. 108 dated March 31, 1943, nine square miles of rugged lava terrain in El Malpais were removed from the public domain for military purposes. [27] Practice bombing missions began soon after the June 15, 1943, declaration of taking in the condemnation case. Officially, the military called the site, Army Air Forces, Kirtland Demolition Bombing Range. McCarty's Crater, at the center of the nine square miles, became the primary target area as indicated by the number of shell fragments and pockmarks found. Although nothing is known of the type of planes or the number of bombs dropped, it was confirmed by the discovery of bomb casings and fuses that the bombs represented general purpose l00-pound bombs containing the nose fuse M103 and tail fuse M-100. [28]

Local residents like Christine Adams, whose parents homesteaded east of McCarty's Crater, remembered the exploding bombs. With the exception of frightening chickens and rattling dishes, it did no apparent harm. [29] The military continued using the bombing range on an intermittent basis for ten months. In April 1944, Kirtland closed the range, stating the area "can only be reached by walking insofar as it is located on the extremely rough terrain of an old lava flow. Since construction and maintenance of targets is impracticable, the range is excess to the needs of this command." [30] The condemnation settlement revested fee title to the private owners, changed the interest to a leasehold in lieu of fee simple, and released the United States from all claims arising from the government's use of the land. The public domain land was released to the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, by Public Land Order 344, dated January 29, 1947. On April 2, 1947, the bombing range officially became public domain. [31]

The U.S. Army in restoring the land to the private and public sector endeavored to locate all unexploded bombs. The stipulation filed in U.S. District Court for New Mexico on November 14, 1944, stated: "It is understood by the Defendant that the United States of America has policed and made an earnest effort to clear the property hereinabove described of all unexploded bombs; however, the Defendant agrees that it is impracticable to locate all unexploded bombs on said lands hereinabove described and . . . the defendant agrees to, and does hereby for itself, its successors and assigns, release and forever discharge the United States of America from any and all claims of whatsoever kind or character that may arise from injuries to person or damage to property resulting from the explosion of unexploded bombs left remaining on said lands by the United States of America." [32]

But the army continued to show concern for public safety in the defunct bombing range. In 1953, the military returned to the lava bombing range to salvage all remaining metal and to search for unexploded bombs. Ordnance experts combed the range and found approximately 80 tons of scrap metal. Captain Edward W. Kerwin reported that the former range, "is safe and free of dangerous and or explosive materials." [33] But the discovery of bombs continues. Local malpais resident, Sleet Raney, escorted Bureau of Land Management Range Conservationist, Les Boothe, to McCarty's Crater in August 1986. They found two unexploded bombs intact in trees 200-300 yards from the crater. [34] At the request of the Bureau of Land Management, the 41st Ordnance Detachment Fort Bliss, Texas, inspected the site. The two 100-pound bombs were detonated. An on-site staff sergeant indicated that from other bomb fuses found in the vicinity, more live bombs are probably in the area. This sentiment is shared by local ranchers, who claimed discovery of bombs 5-6 miles from the impact site. Rio Puerco Resource Area Manager, Herrick Hanks, requested in a letter of January 1987 to the Department of the Army Explosive Safety Board that the military "conduct a surface clearance," a request that never materialized. [35] In 1990, more bombs were discovered.

The end of World War II witnessed agriculture and mining as the two largest employers in the malpais region. By 1950, the population of Grants leveled off at 2,500. The community established itself as the trading center for nearby ranchers, miners, and the few timberman still involved in logging operations. More importantly Grants surpassed San Rafael as the regional commerce center. People from communities like San Rafael, Prewitt, Bluewater, and the few remaining homesteaders on the flanks of the malpais now focused on Grants for business. [36]

In 1950, the malpais region experienced it greatest cycle of boom. Navajo sheepherder, Paddy Martinez, discovered uranium north of Grants. Martinez's discovery touched off a wave of miners and companies to the area. By 1960 Grants' population escalated to 10,274. Many locals found work in the mines. With the increase in population, demand for additional services grew. Banks, schools, hospitals, libraries, and a community college were developed or established during the height of the uranium industry. State Highway 53, graveled in the 1930s became a paved highway in the 1960s. About the same time Interstate 40 through the malpais was built. Grants continued to grow. According to the 1980 census, Grants reached its highest population of 11,451. West of Grants and beyond the city limits, the town of Milan supplied a supporting population of 2,700. [37] On June 19, 1981, Grants and the malpais region separated from Valencia County and formed part of Cibola County with Grants as county seat. [38] The decade of the 1980s, however, was cruel to Grants and the region. Demand for uranium dropped. The economic recession that followed did nothing to revitalize the sagging fortunes of the malpais. Grants lost population and businesses folded up.

Railroad, livestock, timber, and uranium, played major roles in the development of the area. Yet, they all proved to be unstable in providing a long-term buffer from economic recession. Ambitious homesteaders had hoped to beat the odds and make a decent living from the land. Had they reviewed the history of the region, they would have discovered that climate and terrain were the dominant masters rendering the area less than conducive for agricultural pursuits.

Tourism was perhaps the one economic business in the malpais that lacked development and exploitation. The management of the natural and cultural resources in the study area for public use and enjoyment was on the threshold of discovery as the malpais entered the second quarter of the twentieth century.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

elma/history/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2001