|

El Malpais

In the Land of Frozen Fires: A History of Occupation in El Malpais Country |

|

Chapter IX:

TOURISM AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A NATIONAL MONUMENT AND NATIONAL CONSERVATION AREA

Could tourism become the mechanism for expanding the malpais region's economic base? Before 1925, the idea was embryonic. However, with the advent of affordable and efficient automobiles, and the paving of major arteries (U.S. 66 through Grants received a hard surface coating in the 1930s) the public took to the highways in unprecedented numbers. Prominent natural and historic landmarks like the Grand Canyon, Aztec Ruins, Petrified Forest, Chaco Canyon, and El Morro National Monument enticed and beckoned travelers to visit the wonders of the Southwest.

|

|

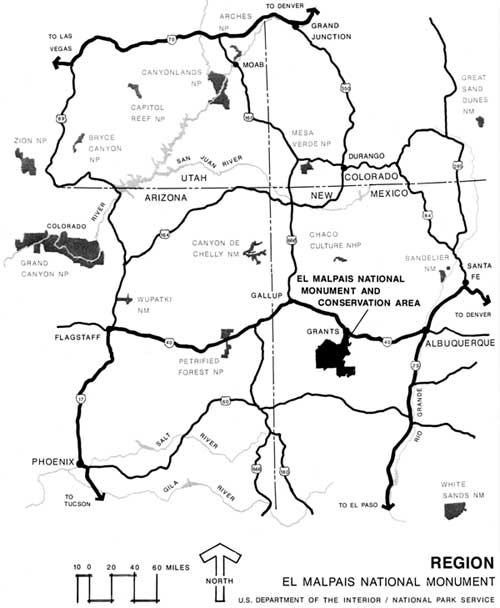

Figure 9. Region Map of El Malpais National Monument. (click on map for a larger image) |

From the earliest Indian inhabitants to the first bedraggled, dusty motorist who drove into William Thigpen's motel in Grants in the 1930s, the lava flows and perpetual ice caves near Bandera Crater had puzzled and aroused curiosity. [1] El Morro National Monument custodian, Evon Z. Vogt, a man of visionary ideals, possessed more than a budding interest in the ice caves. As early as 1934, Custodian Vogt penned a note to Arno B. Cammerer, Director of the National Park Service, expressing his fears over the loss or removal of ice from the caves. [2] Vogt complained that locals and homesteaders alike frequented the cave in the summertime, packing away hundreds of pounds of ice. Unless something was done to protect the area Vogt asserted, all the ice would disappear. An advocate of preservation, Vogt's ultimate proposal recommended protection for the ice caves by planting them under the jurisdiction of El Morro National Monument as an addition to the park. At the minimum, Vogt urged, "The combination of this virgin forest, the Ice Caves, the intriguing wild lava bed, where the experience of discovery can always be had, presents what we think should be set aside in an area of recreation." [3]

Those same words dripped from the pen of Jesse L. Nusbaum, Director of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe. Nusbaum, in a letter to Director Cammerer stated, "Personally I think these caves and their features of sufficient importance to justify their consideration as a separate national monument, or as a part and parcel of the El Morro National Monument." [4] To follow up on Vogt's and Nusbaum's suggestion, Cammerer instructed Yellowstone Park superintendent, Roger Toll, to examine the ice caves. On April 29, 1934, Toll visited the sites. In responding to Cammerer, Toll reported the ice caves interesting, however, they did not, in his opinion, warrant inclusion into the National Park System. He added for good measure that ice caves and lava features were already represented in three national park areas. Moreover, Toll cited that even if extra personnel were assigned to El Morro, they could not be spared to safeguard the vanishing ice. They would be needed, Toll insisted, to protect the inscriptions at El Morro. Because of El Morro's historical importance Toll said, he did not see any value of adding the geological features of a site separated by 16 miles of private lands from El Morro.

Toll's candid letter concluded with one bright note: "It is recommended that this area be dropped from consideration as an addition to the national monument, but that any desired cooperation be extended to the State of New Mexico if the state is interested in securing the area as a state park." [5] Although the state expressed interest in the project, it did not possess the necessary funding to establish an ice caves state park.

Toll's report severely damaged any chance for an ice cave and lava bed monument, but it did not entirely close the door on the subject. In 1936, the National Park Service conducted still another investigation into the merits of establishing a national monument south of Grants. In April 1936, John E. Kell, Regional Inspector and Associate Landscape Architect, National Park Service, examined the lava beds and ice caves. Kell's assessment of the caves closely followed the perceptions of Toll. Kell reported: "the place [ice caves] was too inaccessible and perhaps too small an area to be considered as a park or monument." [6]

Whereas the National Park Service did not consider the ice caves to be of national significance, local citizens and nearby papers did. Local and regional papers expressed the caves and lava as "natural" tourist attractions. The Grants Review, July 23, 1936, remarked on the tourist potential of the region within a few miles of Grants--Acoma pueblo, Inscription Rock, lava beds, extinct volcanoes, and Mount Taylor. [7] An editorial feature in the Silver City Enterprise, while exhorting the completion of a road linking El Paso to Grand Canyon, championed the construction of a highway connecting with the chain of volcanic craters and "the largest ice caves in America." It labeled them prime tourist attractions. The paper suggested that local and state officials combine their efforts to achieve their fruition by a tourist highway. [8]

|

|

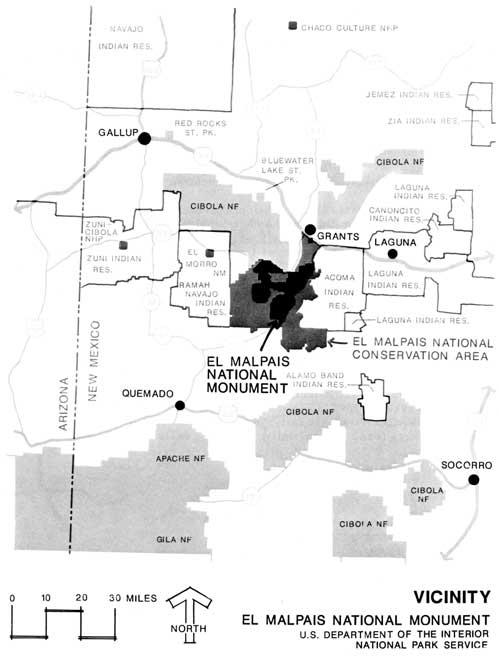

Figure 10. Vicinity Map of El Malpais National Monument. (click on map for a larger image) |

While the National Park Service vacillated and pondered the qualities of the ice caves and lava beds, the number of visitors to the region steadily increased. Sylvestre Mirabal, sheep and land tycoon from San Rafael, owned the ice caves. Although records are sketchy, Mirabal either purchased the ice caves from the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad or through one of the timber companies who had acquired the land from the railroad. [9] Just who discovered the ice caves is a point of conjecture. Certainly the early Native Americans visited the caves judging from the vast array of pottery found in the vicinity. According to David Candelaria, present owner of the ice caves, it was his great-great grandfather, Benito Baca, who first set eyes on the cave sometime in the 1880s. Baca homesteaded two miles from the cave. [10]

Until the 1930s, the ice caves lacked signage of any kind. During the 1930s a poorly marked trail led from the State Highway (present New Mexico 53) to the site. Access to the mouth of the cave remained an odyssey, compelling and challenging inquisitive tourists to crawl and scramble over sharp-edged lava rocks, or work themselves down improvised ladders fashioned from tree trunks and branches in order to glimpse the icy spectacle. [11] Insufficient markers and accessibility problems to the ice caves peaked in July 1938, when three Kentucky schoolteachers stopped to visit the cave. On July 20, the women parked their car adjacent to the ice cave path. Unfortunately, they missed the dim trail and became entangled and disoriented within the catacombed lava. When locals spotted the parked car the next day, suspicions mounted that the people might be in trouble. A search party failed to find the missing persons. Governor Clyde Tingley instructed the State Police to organize a search and rescue mission, eventually involving more than 100 volunteers. On July 23, search and rescue officials found the lost party alive, but suffering badly from exposure, malnourishment, lacerations, and bruises. [12]

|

| Figure 11. The Ice Caves near Bandera Crater were a geological wonder that attracted local and out of state visitors as reflected in this circa 1920 view taken by U.S. Geological photographer W.T. Lee. In 1939, local resident Cecil Moore realized the scenic and commerical value of the Ice Caves. He leased the property from Sylvestre Mirabal. Moore put in wooden stairs to the cave as well as constructing tourist cabins and other facilities to accommodate the growing trend of tourisum in New Mexico. After Mirabal's death ownership of the Ice Caves eventually pased on to David Candelaria, Mirabal's grandson. The Candelarias, David and his wife Cora, have continually operated the Ice Caves since 1946. Photograph credit W.T. Lee, U.S. Geological Survey, Photographic Library, Denver, CO. |

The near-tragedy with the Kentucky schoolteachers prompted an outpouring of letters to papers and government officials to do something with the caves to prevent any further accidents. [13] In response to the episode of the lost women, Albuquerque resident and cave-preservationist Vincent V. Colby, wrote to Harold L. Ickes, Secretary of the Interior. Colby exhorted the secretary to preserve the caves before vandals from nearby lumber companies destroyed the last vestiges of ice. He also remarked on the near-fatal accident involving the teachers. Colby wrote: "There also are no intelligent signs near by. The only small one to be noted is confusing, so much that three tourists only last week, and by misunderstanding this sign, were lost for four days without food or water. Through the greatest luck and with the help of more than a hundred searchers was it possible to find them--just in time." [14]

Colby's letter found its mark, Ickes promptly formed another survey crew to evaluate the ice caves as potential national monument material. In November 1938, a National Park Service technical team from Region III (Southwest Region) comprised of Milton J. McColm, Acting Associate Regional Director; John E. Kell, Associate Landscape Architect; Charles M. Gould, Regional Geologist; and Erik K. Reed, Assistant Archeologist, examined the area. This blue ribbon panel produced a Special Report prepared by all three but submitted by McColm. In conclusion McColm recognized the area held "considerable interest" but questioned whether the large capital outlay required to develop and administer the park was in the best interest of the public. McColm did not feel the area suffered from a high rate of vandalism considering its inaccessibility. In summation, McColm recommended "that no action be taken toward establishing this area [ice caves] as a national monument until further and more comprehensive investigations can be made." [15]

The National Park Service never followed up on McColm's recommendation, and the issue of national monument status died from neglect. In 1943, when the United States Army requested the malpais for a bombing range, the National Park Service reacted: "If it is required by the War Department as a demolition bombing range, certainly under present war conditions that need would far outweigh any doubtful potential value that the area might have as a national monument, and our position would be impossible to justify if we offered any objection to the proposed use. I recommend that the Army be advised accordingly." [16]

During the 1930s and 1940s the National Park Service manifested little more than a passing interest in the ice caves and lava flows. But local homesteader, Cecil Moore, perceived the ice caves as a potentially rich tourist attraction. In 1938, Moore leased the ice caves from owner Sylvestre Mirabal. Among Moore's first tasks was to upgrade the approach to the cave and construct a suitable stairway ascending into the cave. By October 1938, Moore had improved the pathway and completed a 75-foot stairway leading down to the mouth of the cave. [17] Moore envisioned expansion of the ice cave operation to include installation of a dude ranch enterprise. After completing the path and stairs, he initiated construction of a series of rustic cabins, restaurant, service station, and bar to cater to the motoring public. By June 19, 1939, Moore reported to the National Park Service that he had completed four of his cabins, as well as a restaurant, and trail approach to the ice cave. Moore completed his series of overnight cabins and even installed a picnic ground. Visitors to the Ice Caves paid 25 cents admission. The money went towards maintenance of the trail and wooden staircase. [18]

Because of the deteriorated condition of Highway 53, Moore requested the National Park Service to exert any influence it had with the State in obtaining either a graveled or oiled surface highway in front of his business. This he added would make the area attractive for tourists. [19] The National Park Service responded that it was impossible "to take any definite hand in the improving of the approach road" to his property although the Service would encourage the State to do so because of the upcoming Coronado Quadrennial. [20] Moore remained in control of the ice caves for less than four years. Following the death of Sylvestre Mirabal in 1939, the caves remained in the Mirabal family but were still leased to Moore. Eventually, ownership of the caves passed to Mirabal's daughter, Prudenciana Mirabal Candelaria. The Candelarias, Prudenciana and Manuel Antonio, operated the Ice Caves sporadically during World War II, primarily in a caretaker status. For a while, it evolved into a cowboy camp. [21] In 1946, the Candelarias' son, David, was encouraged to manage the ice caves. Under the management of David Candelaria and his wife Cora, the ice caves prospered and grew into a full-time operation. They added more cabins and removed the campground to avoid competition with El Morro's campground.

While the Candelarias improved their facilities, they strived to preserve the unique geological features of the area. [22] The Candelarias waged endless battles with local and State bureaucracies to modernize the ice caves and the region. Through their efforts and others like them, they succeeded in bringing electricity to the Zuni Mountain settlements in 1955. In 1966, State Highway 53 from Grants to the ice caves was paved. This seemingly insignificant act prompted more vacationers to detour from U.S. 66 and partially constructed Interstate 40 to visit the ice caves. [23]

|

| Figure 12. Until the paving of Route 66 in the 1930s, travel in El Malpais Country could be an adventure. Pot holes, loose livestock, and axle-deep mud were common encounters. Photograph taken by W.T. Lee about 1920 near Laguna, New Mexico. U.S. Geological Survey, Photographic Library, Denver, CO. |

While the ice caves flourished under the capable leadership of the Candelarias, another tourist facility emerged on the east side of the malpais. Local ranchers spearheaded by Mark and Ina Elkins and their close friend, Artie Bibo, envisioned the establishment of the Kowina Foundation. The goal of the Kowina Foundation was to honor the western pioneers and the rich, proud heritage of the Acoma Indians. Artie Bibo donated land for the site, and the Elkins gave charitably of their finances to erect the structure on top of Cebolleta Mesa. Dedicated May 9, 1970, the facility contained a collection of artifacts devoted to the pioneers and the area and gave visitors an opportunity to examine the extensive Indian pueblo ruins on top of the mesa. Considering publicity of the site scarcely advanced beyond the local papers, attendance remained low. Because of the death of Mr. Bibo and the failing health of Mark Elkins, the facility and all its contents were sold about 1980 to the Acoma Indians. [24]

During the period of the Bibos and Elkins project, the National Park Service renewed its interest in the malpais. In 1969, El Malpais as it was now termed, became eligible for natural landmark status by action of the Secretary of the Interior. The National Park Service submitted "A Study of Alternatives--El Malpais" and released in 1970 and 1971 its preliminary findings. The study offered two alternatives: one, that the area continue to be managed by the Bureau of Land Management as an Outstanding Natural Area; second, that the National Park Service manage the area as a national monument. The National Park Service now deemed El Malpais' resources of "high enough quality to be considered for inclusion in the National Park System." But the report also expressed an opinion that management responsibilities could probably be best accomplished through the Bureau of Land Management, whose jurisdiction and longstanding relationship with the malpais and its inhabitants was firmly cemented. [25] State Bureau of Land Management officers concurred with the findings and reiterated the Bureau's position, "that protection, preservation, and management of the Malpais area can be accomplished under the Classification and Multiple Use Act of September 19, 1964." [26]

The biggest obstacle to the creation of a national monument remained the status of the ice caves and Bandera Crater. The National Park Study cited that a national monument could only succeed via the inclusion of the ice caves and Bandera Crater as a nucleus of the park proposal. "To try to establish a national monument without these land resources severely undermines the suitability argument upon which the National Park Service proposal is based. The superlative interpretive story which could be told about the vivid volcanic history of El Malpais is incomplete with the elimination of these classical volcanic illustrations from that story," the study concluded. [27] The Candelarias, indeed, did not desire to sell their beloved caves, craters, and lava beds. They pondered the future of their children. Perhaps their offspring might want to manage the operations. Moreover, while the debate about making the area a national monument raged, officials neglected to include the Candelarias in some of the discussions. On May 8, 1973, New Mexico Congressman, Harold Runnells introduced House Rules 7607, a bill to establish El Malpais-Grants New Mexico. That bill succumbed because of the influence of the Candelarias who adamantly refused to sell their property. [28]

|

|

Figure 13. Bandera Crater, view taken by W.T. Lee about 1920. Credit U.S. Geological Survey. Photographic Library, Denver, Co. |

Meanwhile, the State expressed interest in creating a state park in the malpais. That idea foundered when the New Mexico legislature rejected the state park proposal in May 1973. Instead, the State supported a plan whereby El Malpais would be managed as a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) outstanding natural area with natural landmark status. But nothing came of the proposal. [29]

Still Grants citizens clamored for an El Malpais National Monument. Another decade passed. Finally, with the Candelaria children now grown and not expressing a desire to manage the commercial caves, the Candelarias agreed to sell their holdings in 1986 to the National Park Service. Public Law 100-225 signed on December 31, 1987, officially created El Malpais National Monument.

Officials in Grants perceive the national monument as the cornerstone in the town's attempt to create a new economy based on tourism. As Grants enters the 1990s, the community is embarking on an ambitious plan to get motorists from I-40 to stop and visit the nearby attractions. The economic history of Grants is a cycle of boom and bust. One hundred years ago the railroad brought opportunity to the lava country. Timber followed sheep and cattle. But they too, failed. Large scale carrot growing operations flourished for two decades before failing. In the mid 1950s uranium ushered in another wave of economic prosperity until its demise in the 1980s. In the 1990s Grants looks towards tourism as its next economic lifeline. Only time will tell whether tourism is a panacea or merely a stop gap in the perpetual up and down economic cycle that has been a hallmark of the history of el malpais. Given the prior human history, it seems fairly certain that the Indians, Hispanics, and Anglos of El Malpais region can and will adjust to socio-economic fluctuations.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

elma/history/chap9.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2001