|

Fort Davis

A Special Place, A Sacred Trust: Preserving the Fort Davis Story |

|

Chapter One:

Fort Davis and the Western Story

Standing on the parade ground of old Fort Davis, high in the Davis Mountains of far west Texas, one sees much more than the strikingly beautiful landscape of Limpia Canyon. Heralded in song and legend, the plains and mountains of west Texas (known as the Trans-Pecos region) have witnessed not only the unfolding of the saga of the American frontier. They also are home to the story of the American experience, from its precontact cultures down to the late-twentieth century. As the steward of Fort Davis National Historic Site, the National Park Service engages constantly in the discussion of the meaning of the far western frontier. In addition, its staff, volunteers, and Friends group must preserve a highly valuable architectural and historic resource to meet the needs of visitors seeking an accurate portrayal of what is often described as the "best example of the frontier military in the Southwest."

The competing forces of history and myth that suffuse the story of Fort Davis begin with the construction of the post itself, built in the heady days of the westward surge following the War with Mexico and the "rush" to the California gold fields. From the earliest encampment of American soldiers in 1854, to the re-establishment of the Army post after the Civil War (1867), to the abandonment of Fort Davis in 1891, the Davis Mountains hosted units of the Indian-fighting forces that would be enshrined in popular culture throughout the twentieth century. Yet few visitors come away from the site knowing the full impact of the ecological and human experience that marked life at Fort Davis, or of the actions taken by their public servants to guarantee to future generations access to the national treasure that the U.S. Congress in 1961 entrusted to the park service.

If one walked the 460-acre post with a history text in one's hand, one would recognize no less a spectacle than that offered by the beauty of the red cliffs and the green valley of the Limpia. Fort Davis included all the topics that have come in recent years to constitute the "new western" history: issues of race, class, gender, power, and environment. These concepts, studied for the first time in the revisionist era of the 1960s and 1970s, held that the "nation-building" story that for decades had explained the spread of American civilization across the continent had ignored or deemphasized problems caused by urbanization, modernization, and improvement of the American standard of living. For the past two decades and more the scholarly revision of the westward movement crafted a tale that would challenge prevailing assumptions of the western military and subsequent settlement. Yet the real life of the fort, as chronicled so well by park service historian Robert M. Utley, and later Robert Wooster, would one day emerge from the mists of the past to broaden the Fort Davis story. It would also provide the park service with one of its first opportunities at the end of the twentieth century to fashion a narrative of achievement and conflict that the actual inhabitants of the fort, town, and mountainous region might recognize, were they to return to the post today. [1]

|

|

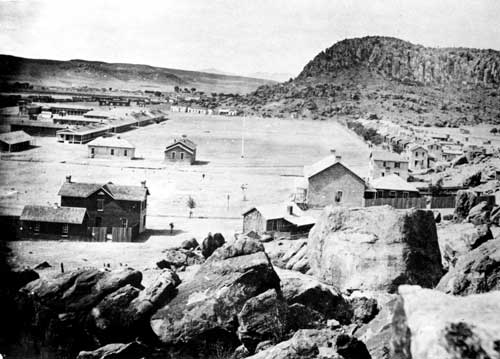

Figure 1. Historic Photograph Looking South

with Chapel to the left of Flagstaff (c. 1886). Courtesy of Fort Davis NHS. |

Historians of the arid West have noted the extremes of environment that differentiate the Davis Mountains region from the source of most of the westward movement's population: the humid climate of the eastern United States. At almost 5,000 feet in altitude, Fort Davis shares an ecology more akin to its western neighbors of New Mexico and Arizona, and its southern neighbor of Mexico, than it does the state in which it resides. Where east Texas boasts abundant rainfall (the city of Dallas has nearly as much annual moisture as "rainy" Seattle, Washington), which permits agriculture and urbanization on a large scale, the Davis Mountains receive only enough rain in good years to support cattle ranching and small-scale irrigated farming. Distance, isolation, aridity, and altitude have influenced all cultures that have crossed the Trans-Pecos, from the earliest precontact societies of 9000 BC to the contemporary tourists and urban expatriates who flock to Fort Davis for its cool summers and mild winters. Limpia Creek, which in Spanish means "clear," cuts through the mountains on its journey to the Pecos River basin below on lands that Spanish explorers crossed in search of gold and ancient civilizations.

Native cultures found in the Davis Mountains what still endures today: game, wood, water, and temperate weather. Migration from the settled communities to the northwest (the New Mexican village-dwellers whom the Spanish generically referred to as the "Pueblos") had reached the Trans-Pecos about a century before Coronado, but left no permanent mark on the region. More prominent were the nomadic peoples known as the "Jumanos," whom the first Spanish observed traveling through the mountain corridors on their journeys into modern-day Mexico. By 1900, the Jumanos had been assimilated into Mexican society. The Spanish also found bands of people whom they called "Apaches." Because of their ability to survive and prosper over a vast stretch of desert, canyon, and mountain terrain, the Spanish called the area "El Gran Apacheria," reaching from Austin on the east to Tucson on the west, and from Wichita on the north to Chihuahua on the south.

Of these bands, whose own names for themselves translated to "human beings" or more simply "the people," the Spanish recognized one group as frequenting the area most often; the Mescalero Apache. Named for the mescal or "agave" plant whose buds gave them energy to survive in the desert, the Mescaleros considered as their homelands an area from southern New Mexico (modern-day Ruidoso in the Sierra Blanca) to the Pecos valley of Texas, and south hundreds of miles into central Mexico. Their cousins, the Lipan Apaches of south Texas, also passed through the Davis Mountains, as would the most feared warriors of the southern Plains, the Comanches (whose name derived from the Ute word for "enemies"). It was no coincidence that so many groups with aggressive tendencies traversed the region, given the harshness of the landscape for people with limited technology and resources. Antonio de Espejo, the first Spanish explorer to walk through Limpia Canyon (1582-83), noted the difficulty of conquest awaiting Spain if it wished to recreate in far west Texas its successes of Mexico and Peru. Thus it was no surprise that the first permanent Spanish settlement of the Southwest, the New Mexico-bound party under Don Juan de Onate, followed not Espejo's route north along the Rio Concho and Pecos River, but the more westerly Rio Grande in 1598 to the northern Pueblo communities near modem-day Santa Fe.

The story of the Spanish Southwest has been analyzed at great length, first with the "Borderlands" scholarship of Herbert Bolton in the 1920s and 1930s, and later with the "Chicano school" of the 1960s and 1970s. Each disagreed with the other's assumptions about the merits of Spanish intrusion north from Mexico; the Borderlands interpretation heralding the glamour of the conquistadors, while the Chicanos decried the elitism and violence of the soldiers, settlers, and priests. For west Texas, however, the story was more complex. No major Spanish communities were founded along the lower Rio Grande, nor were Catholic priests any more successful with proselytizing at their missions. Not until 1760 (some six generations after Onate's journey) did the Spanish appear south of modern-day Fort Davis to erect El Presidio del Norte (the present-day border town of Presidio) to protect the Guadalupe mission. Thus the Trans-Pecos region knew little of the struggles that shaped the history of New Mexico and California, where Spaniard and Native fought and accommodated each other's presence, and where both groups created the tragic legacy of victimization and the birth of "La Raza," the "new race" of mixed people that emanated from three centuries of Spanish-Indian interaction.

|

|

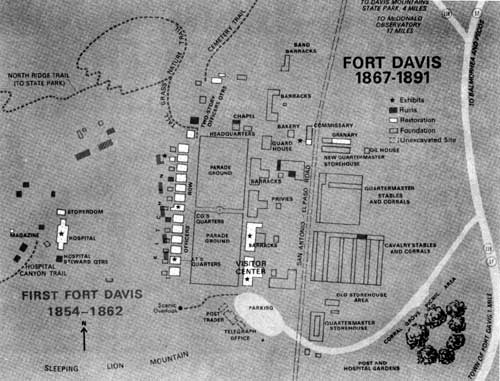

Figure 2. Fort Davis Site Map. Courtesy Fort Davis National Historic Site. (click on the map for an enlargement in a new window) |

Upon the eviction in 1821 of the Spanish royal government from Mexico and the Southwest, the new leadership of the Republic of Mexico assumed control of the Trans-Pecos region. They could not, in their single generation of management of the Southwest, overcome the challenges of environment and ethnicity that had stymied Spanish royal officials. Mexico, with little money and less experience, could not carve out of the region a permanent presence to avail itself of the resources awaiting the next conqueror, the young United States of America. In 1830, Lieutenant Colonel Jose Ronquillo did petition Mexican authorities for the grant of a 2,345-square mile section of the Trans-Pecos that included the Davis Mountains and the future Fort Davis. But the impending crisis to the east, known as the Texas Revolution, drew the attention of Mexican leaders like President Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana away towards San Antonio. From the loss of the Alamo in 1836 to the declaration of Texas independence (1836), Mexico had little time to contemplate the uses of the Davis Mountains, leaving the area for the Americans to conquer and develop in the 1840s and 1850s.

That experience began within months of the arrival in 1846 of U.S. forces in the Southwest under General Stephen Watts Kearny. Kearny focused his attention on the annexation of New Mexico and the conquest of California. Following the Mexican American War, U.S. officers fanned out across the Southwest to record information for future military and civilian use. The U.S. Army, under the command of Captain William Randolph Marcy, passed one hundred miles north of the future site of Fort Davis in the fall of 1849, along what is today the route of Interstate 20. In March of that year, Marcy sent a detachment under the command of Lieutenants William H.C. Whiting and William F. "Baldy" Smith to survey West Texas. They followed an old Indian trail through a pass which they named "Wild Rose," and Whiting called the stream that flowed through the mountains "Limpia." Beyond the pass in a grove of cottonwood trees, the Whiting-Smith party stopped at what they called "Painted Comanche Camp;" the future site of Fort Davis.

The Army survey had been undertaken because of the surge of travelers through the Southwest to the California gold fields, discovered in January 1848 but not publicized until the following year. Known as the "49ers," these goldseekers took a series of routes westward, the most promising being the San Antonio-El Paso road through the Trans-Pecos. Because of its level conditions, all-weather access, and the wood and water of the Davis Mountains, the road appealed to travelers who faced more taxing routes either around South America, or across the high-walled Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada. The presence of nomadic Indian tribes in the region also required the security services of the Army, and in 1854 the War Department sent to the Davis Mountains Brevet Major General Persifor Smith to establish the first Fort Davis.

Smith had come to far west Texas to open a series of six posts, and to secure the transcontinental route of the 32nd parallel outlined by Congress in the 1853 Pacific Railway surveys. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (for whom the fort and mountains were named) had sought a string of forts along the Rio Grande, but Smith informed his superiors that the valley was too barren and forbidding for ease of travel. By suggesting the Limpia Canyon for location of six companies of the Eighth Infantry, Smith guaranteed the presence in west Texas of military forces that would last for the next five decades. Smith began by negotiating with John James, a large landowner in the Davis Mountains, to lease to the Army 640 acres for the post, with annual rent of $300. The government also received a purchase option to exercise within five years at $10 per acre; an option that the Army never pursued.

Little remains of this first military site in the Davis Mountains, but official records indicate that Smith and his successors in command prior to 1860 grappled with the same conditions of environment, ethnicity, and isolation that had plagued the efforts of Spain and Mexico. In 1854 the soldiers of the 8th Infantry constructed either tents or modest "jacales" of oak and cottonwood pickers, neither of which could withstand the harshness of the west Texas winter. Soon thereafter the troops processed lime in a kiln built some thirty miles from the fort, and also went into the Davis Mountains for lumber, which they milled on site. By 1857 the post had permanent barracks built of stone, although most structures still had a temporary look about them. Uncertainty about the final location of the Pacific railroad and access routes through the Davis Mountains kept Congress from funding Fort Davis adequately, although troop strength by the mid-1850s stood at 400, making the fort one of the West's largest.

The pre-Civil War Army never had the numbers nor funds to effect substantial change in the patterns of Indian migration or attacks upon travelers. In order to meet demands for protection with limited resources, Secretary of War Davis acquired from Congress $30,000 for his "camel experiment," wherein the Army purchased camels from the Middle East and brought them to the American Southwest for use in the deserts. On July 17, 1857, former U.S. Navy Lieutenant Edward F. Beale led the Camel Corps through Fort Davis enroute to their posting in Arizona, and in 1859 the camels were used again to locate a more direct route from San Antonio to the fort. The experiment, despite the worthiness of the animals, failed in large measure because of costs (support of one camel corpsman was two to four times that of infantry), and because of the offensive smell and behavior of the camels. When Secretary Davis left office in 1857, the camel corps lost its chief advocate, and by the start of the Civil War the experiment had ended.

Life at the post before 1861 bore a strong resemblance to the more prominent post-Civil War Fort Davis. Stage and mall service came within one mile of the fort, with the stop known as "La Limpia." Soon thereafter, attacks upon mall trains by Mescalero Apaches had begun, and Fort Davis troops spent a good deal of time chasing them through the mountains to Mexico. Duty at the post in time of peace, however, was as boring as anywhere else in the isolated West. Officers complained about low pay, high prices caused by transportation difficulties, and the fear of wasting their careers in the middle of nowhere. Enlisted men at pre-Civil War Fort Davis were over 50 percent foreign born. According to the 1860 U.S. Census, only six of the 94 soldiers at Fort Davis came from rural backgrounds (even though the nation as a whole was only 20 percent urban). Their diet paralleled that of other frontier outposts; heavy on such high-energy substances as starch, carbohydrates, and sugars. The post commanders, with no American farms nearby, purchased fruits and vegetables from Mexico. There too went soldiers on leave for recreation, though many found the Mexican "ambiente" too exotic for their tastes. This ethnic mingling influenced the civilian community that surrounded the fort. The 1860 census revealed that 50 of the 70 residents were Hispanic, and nearly all the adults worked for the post as laundresses, laborers, servants, and stockmen.

As the nation moved by 1860 to the brink of civil conflict, the U.S. Army began removing troops from its western outposts to prepare for engagements in the East. That year Lieutenant Colonel Washington Seawell, commander at Fort Davis, asked his superiors to remove his forces to San Antonio, which the Army agreed to do. In 1860 also, voters in Texas were asked if they wished to secede from the Union. Fort Davis residents, linked politically and economically to the national government, decided 48-0 to reject secession. Unfortunately, the Texas electorate, angry not only at the demands of northerners to end slavery, but also at the failure of the Army to stop Indian raiding, decided to leave the Union. General David Twiggs, commander of the U.S. Military Department of Texas, then surrendered all army posts (including Fort Davis) in February 1861 to the Confederate States of America (CSA), and in April 1861 the Fort Davis troops began their retreat to San Antonio.

Remaining behind at the abandoned site were several Hispanic families, plus the German immigrant Anton Dietrick (known locally as "Diedrick Dutchover"), who had married into an Hispanic family and become a substantial landowner and rancher. Rebel forces surprised the Fort Davis units on the road to San Antonio, who then were captured and held until their release in 1863. Soon after abandonment, CSA recruits came to the fort to create a garrison to protect west Texas against Indian raids, as the tribes showed no respect for the enemies of the rebel adversaries, the Union Army. By July 1861, all but twenty of the CSA troopers stationed at Fort Davis had left with Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor on his invasion of southern New Mexico and Arizona, leaving the Trans-Pecos vulnerable to attack by the Mescaleros. This in turn contributed to the embarrassing venture of August 11, 1861, when CSA Lieutenant Reuben E. Mays and his party rode out of Fort Davis only to be decimated by Mescalero Apaches.

By October of that year, the CSA could only staff Fort Davis with 62 troopers. Then in November came Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, whose three regiments of Texas Mounted Volunteers were on their way to their ill-fated confrontation in northern New Mexico at the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Upon his defeat at the hands of a combined force of Union regulars, and New Mexico and Colorado Volunteers, Sibley again passed through Fort Davis, taking with him the remaining rebel troops. Apaches then came down out of the hills to destroy what remained of Fort Davis, driving Diedrick Dutchover and his party staying at the post to the safety of Presidio. Ironically, that last unit of CSA soldiers at Fort Davis had been predominantly Hispanic, led by Captain Angel Navarro.

The return of Union forces to west Texas took some time, as the war in the East moved toward closure in 1864-1865. The departmental commander of New Mexico, Brigadier General James H. Carleton, had sent down from Santa Fe in September 1862 a party under the command of Captain E.D. Shirland. The Union troops found Fort Davis mostly in ruins, with furnishings and supplies sold by the CSA to the Hispanic residents of the border. Not until 1865 would Army forces reoccupy the west Texas region, and even then the focus was on either the presence in Mexico of French troops under the leadership of Maximilian, or the need to implement the policies of Reconstruction in eastern Texas. Yet the quickened pace of travel along the San Antonio-El Paso road after the war brought a new round of Indian raiding, which the Army met in 1867 by reopening Fort Davis. Two years later the post had become the headquarters for the Presidio command of the 5th Military District of Texas, and the fort would remain in operation throughout the height of the Indian wars of the 1870s and 1880s.

By orders of the Department of Texas, the Army staffed Fort Davis in 1867 with companies of the Ninth Cavalry, composed of black soldiers recruited for the segregated units created after 1866 to permit freed slaves to serve their country in uniform (as they had done in the latter stages of the Civil War). Eventually all four black units would be assigned to Fort Davis: the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Led at first by Lieutenant Colonel Wesley Merritt, a Civil War hero, the 9th Cavalry had over 50 percent Civil War veterans. The fort contributed to the re-establishment of the nation's military presence throughout west Texas and southern New Mexico, with several posts housing black troopers. Merritt set his soldiers and civilian employees to work rebuilding Fort Davis outside the canyon walls of the first site, using two steam-powered sawmills to cut timber. Soldiers also quarried sandstone from the nearby cliffs, and burned lime for mortar at the post.

Expansion of the fort led to more encounters with Indians in the Trans-Pecos (19 in all from 1869-1877), which in turn drew attention to the security provided by Fort Davis. In 1871 Lieutenant Colonel William ("Pecos Bill") Shafter took command as increased Indian activities throughout west Texas reduced the fort to 110 soldiers. Shafter's successor, Colonel George Andrews, commanded Fort Davis from 1872-1878, and sent out few parties to fight Indians. Much of the black troopers' duty involved protecting the stage and mail stations and routes, along with construction work at Fort Davis. By the late 1870s the troopers had worked on military road construction, and strung 91 miles of telegraph wire as part of the El Paso-San Antonio communication link. Robert Wooster, in his History of Fort Davis, Texas (1990), noted that many civilians in the area were white CSA sympathizers who saw the Army as a symbol of their defeat, while free black soldiers were reminders of the "lost world" of the Confederacy. Often the stage and mail drivers disliked the black Army escorts, even though the stage company owners preferred to use soldiers rather than pay for their own scouts and guards.

The volume of Indian raiding did not abate throughout the early 1870s, and at one point officials from the U.S. customs office and the Office of Indian Affairs called for removal of troops from Fort Davis to Presidio. The state of Texas stepped in to help the U.S. Army with law enforcement on the frontier, dispatching in 1880 a unit of the famed "Texas Rangers" to Fort Davis. Like their civilian counterparts, the Rangers were often rebel veterans who opposed the presence of black soldiers in west Texas. Despite this attitude, the Army commanders not only continued the use of the 9th Cavalry; they also employed in the 1870s members of the famed "Seminole Negro scouts," formed by blacks intermarried with Seminole Indians who had fled the Indian Territory before 1860 to find shelter in Mexico. The scouts worked out of several posts in west Texas, and provided invaluable service with their stamina, knowledge of the land and of Indian ways, and their seeming indifference to the racial animosity generated by their presence. [2]

Activity at Fort Davis reached its peak in 1880, when the prominent Warm Springs chief, Victorio, refused to return to the Apache reservation at San Carlos, Arizona. He wished instead to have a reservation at Ojo Caliente in the San Mateo Mountains. John Briggs, a post guide at Fort Davis, was sent to inspect the Mescalero reservation in response to rumors that it had become a supply center for potential outbreaks by Mescaleros and Chiricahuas. The latter bands, led by Geronimo, had frightened settlers from Tucson to El Paso in the 1 870s, and fears remained that they would seek shelter in the mountainous areas along the Mexican border. The Army in anticipation of this action also built in August 1879 Camp Pena Colorado, a "sub-post" to the east of Fort Davis (south of modern-day Marathon). On July 30, 1880, U.S. forces under the command of Colonel Benjamin Grierson, soon to become commander at Fort Davis, met Victorio's band at the Battle of Tinaja de las Palmas, south of the modern-day Sierra Blanca. After another fight with Victorio north of Van Horn, Texas, (Rattlesnake Springs), Victorio withdrew across the Rio Grande. Grierson's troops drove Victorio into Mexico, where Mexican soldiers under Colonel Joaquin Terrazas killed him in battle. Fort Davis and the Trans-Pecos would see no more major confrontations with the Apaches, although on October 18, 1880 a band of Apaches under the war chief Nana stole horses from the fort's grazing pasture.

Perhaps because of the strong presence of U.S. forces in the Davis mountains, Fort Davis did not experience the engagement of places like the Little Bighorn Battlefield, Big Hole Battlefield, and other western military historic sites now managed by the National Park Service. Yet life at the post in the years after the Civil War, especially beyond 1880, was at once tedious and colorful. Robert Wooster defined "health, race, and discipline" as the critical variables for commanders and soldiers alike at the fort. As a frontier site, Fort Davis (both town and post) had its share of violence and conflict; both exacerbated by the awkward presence of black troopers in large numbers. Wooster noted the story that the Jesse Evans gang, led by an associate of the New Mexican outlaw, Billy the Kid, had come down in 1880 from the Lincoln County wars to harrass the citizenry of the Davis Mountains. The Texas Rangers based at Fort Davis had captured Evans, and rumors flew that the "Kid" would appear in town to rescue his friend. No such event transpired, but its potential demonstrated the uncertainty of law and order in the Trans-Pecos area in the late nineteenth century.

Matters of hygiene and health care, always a problem in the close quarters of military life, underwent scrutiny at Fort Davis because of the post's isolation and difficult mission. Assistant Surgeon Daniel Wiesel came to Fort Davis in 1868 with orders to improve conditions of diet, exercise, and personal cleanliness. He instituted a post garden tended by soldiers to increase the supply of fresh fruits and vegetables, and also prescribed more bathing in Limpia Creek to ward off parasites and germs. Under Wiesel, the mortality rate at Fort Davis was one-third of the Army's average, as was the rate of illness. Medical discharge, a common problem throughout the service, stood at Fort Davis at 60 percent of the service average. Wiesel and his successors, however, had less opportunity to reduce the scourge of alcoholism, which afflicted all military posts in the West.

Racial dynamics posed their share of challenges to the staff and line of Fort Davis, given the post's location near Mexico, its hosting of the black units of a segregated Army, and the isolated conditions that bred both cultural accommodation and cultural stress. Intermarriage between soldiers and local women was usually limited to black-Hispanic liaisons; a situation somewhat surprising given Texas' proscriptions on interracial marriage. More sensational for Fort Davis, however, was the celebrated court-martial in 1881 of the post commissary officer, Second Lieutenant Henry 0. Flipper, the first black graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Upon graduation from the academy in 1877, Flipper had served at Fort Sill, Indian Territory, under the future Fort Davis commander, Colonel Benjamin Grierson. Flipper came to Fort Davis in 1880, but less than one year later faced charges of mismanagement of post funds. His books were poorly kept, and he could not account for $2,400 in receipts. He sought to cover the shortfall with royalty payments pending from his upcoming autobiography; a situation which never materialized. Post gossip held that Flipper had been too bold with the sister of one of the white officers at the fort, escorting her on buggy rides on Sunday afternoons that scandalized other officers and white citizens in town. At his court-martial hearing, held in the post chapel, other residents of Fort Davis collected over $1,700 in one day to help Flipper meet his expenses, but the military tribunal stripped him of his commission for "conduct unbecoming of an officer and a gentleman." Flipper then left the service and moved to El Paso, and started a second career in the Southwest and in Mexico as a mining engineer and translator of Spanish.

The irony of the Flipper experience was that on balance, black soldiers had more opportunity within the service than they would have had as civilians in segregated Texas. The post chaplains held classes in the chapel for soldiers who wanted to learn to read and write; something denied by the mid-1870s to many blacks in both the North and South as Reconstruction came to an end. The post library boasted in 1876 a total of 1,600 volumes, and soldiers and officers alike utilized its services. Then under the command of Colonel Grierson (1882-1885), Fort Davis witnessed its last major initiative for upgrading and improvement of facilities to benefit the lives of the soldiers. Grierson well known for his Indian-fighting and his support of black units, arrived in the Davis Mountains after the major confrontations with Indians had ended. General William T. Sherman, commanding general of the Army, had wanted to locate all primary western posts along railroad routes for matters of efficiency and economy of service. This jeopardized Fort Davis, as the Army in 1884 made Camp Pena Colorado a separate post, built Camp Rice (near old Fort Quitman) in 1882 as a subpost of Fort Davis, and even stationed Fort Davis troops for a time in 1882-1883 at Presidio.

Under Colonel Grierson, Fort Davis held off these encroachments, and expanded its troop strength in 1884 to 39 officers and 643 men. The commander also petitioned his superiors to expend $81,000 for post improvements from 1882-1885, not all of which he received. At the same time, Grierson was motivated (like other officers of the day) by a desire for his own financial security. A larger post, with more construction work for local contractors, would also create the impression of economic vitality that would draw new settlers. The colonel set out to purchase or lease lands in the Trans-Pecos area, owning at one time nearly 45,000 acres, which included 126 town lots in the community of Valentine, west of Fort Davis on the road to El Paso. In like manner, the commander of the black Seminole scouts, Lieutenant John Bullis, acquired title to 53,500 acres of land in Pecos County to the north of the post.

Fort Davis and the surrounding area never grew as Grierson had hoped, even though he and his family labored to put down roots in the Davis Mountains. Opportunities for his soldiers also slipped away as the Indian wars began to fade from memory, making Fort Davis vulnerable to budget-cutting officials in the War Department and the administration of President Grover Cleveland. Grierson and his officers were also aware of the Hispanic "red-light" district one half mile north of the post called "Chihuahua." By 1880 the town of Fort Davis (some 792 people) would be over 67 percent Hispanic. There soldiers found entertainment, excitement, and sin in equal measure away from the prying eyes of the white townsfolk or of their own officers.

By 1885 Grierson realized that his tenure at Fort Davis would be limited, and in March the 10th Cavalry received orders to transfer to Whipple Barracks in north-central Arizona. There they would participate in the campaign in Mexico to find Geronimo, while their white replacements, the Third Cavalry, would oversee the gradual abandonment of the fort on Limpia Creek. The post-military future of Fort Davis was already arriving, as in the late-1880s a Presbyterian minister named William Bloys would preach in the post chapel on alternate Sundays with Methodist and Baptist clergy. The town also clung to its Republican sympathies, given the long relationship with military personnel and defense spending in the Davis Mountains. Conditions deteriorated as budget cuts made it more difficult to maintain the adobe structures, and the limited water supply contributed to diseases like dysentery. Once the last scout for Indians was completed in February 1888, it would be but a matter of time before the U.S. Army called upon Fort Davis to close its doors.

The decision to deactivate one of the West's more celebrated posts came in 1891, when Secretary of War Redfield Proctor realigned the West's military installations. The last major encounter between the Army and Indian resistance had ended at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in December 1890. While tragic, this incident had reminded military officials that few tribes any longer posed a threat to the well-being of American settlement. Fort Davis, isolated and distant from railroad traffic (the nearest railhead was 20 miles southwest at Marfa), and situated on land that the military did not own, thus became a casualty of the changing dynamics of western military defense. In an interesting twist, the local elite did not engage in the supplication familiar to many other western communities in danger of losing their major source of federal income. Perhaps because most of the community was non-white, there was little awareness of the means of influencing the federal government to maintain a military post that the service no longer found useful. Perhaps the low incomes of Fort Davis residents also kept them from funding a full-scale lobbying effort. Perhaps the small number of concerned citizens limited their appeal. For whatever reason, in June 1891 the last soldiers marched out of the post and down Limpia Creek on their way to history.

Those soldiers, settlers, and service workers at Fort Davis could not have known of the fascination that was already building among military buffs and historians alike for the rapidly disappearing western frontier, and its symbols of conquest and achievement. It is not surprising that two years after the closure of Fort Davis, a young history professor from the University of Wisconsin, Frederick Jackson Turner, would deliver to an audience of academics in Chicago his now-famous "Frontier thesis." In that forty-page treatise marked by powerful phraseology and sweeping generalization, Turner would speak as much to the uncertain future of large urban centers, advanced technology, and the impersonal nature of twentieth century life, as he would the bygone days of forests, fields, and streams of the "mythic West" of his youth. The longing for a simpler life that Turner suggested to his listeners (and later legions of readers) might explain how the struggle of soldiers at Fort Davis to wrest the Trans-Pecos wilderness from nature and the Native bands who called it home would become, some three generations later, the location of Fort Davis National Historic Site.

|

VISITATION STATISTICS

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure 3. Visitation Data for Fort Davis (1963-1995). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foda/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2002