|

Fort Davis

A Special Place, A Sacred Trust: Preserving the Fort Davis Story |

|

Chapter Two:

Closing a Fort, Preserving a Memory: Private Power and Public Initiative in Fort Davis, 1890-1941

When then—Senator Redfield Proctor alighted from his stagecoach in Fort Davis in the late 1880s, he observed a community and post whose future neither he nor they could predict for the coming century. At the time the chairman of the U.S. Senate Military Affairs Committee, Proctor wanted to see for himself the value of retaining Fort Davis in the post-Indian wars age. Carlysle Raht, author of The Romance of Davis Mountains and Big Bend Country (1918), interviewed people who remembered the eastern senator's visit a generation earlier. Wearing a top hat and frock coat more appropriate for the halls of Congress than the streets of west Texas, Proctor ignored the fact that, in the words of Raht, "up to this time, the Government had been installing modern conveniences, such as bath tubs and plumbing, in the post buildings." The Vermont senator instead "found a very dry desert country, upon which he pronounced the verdict of 'no good."' Since no other of Proctor's colleagues would visit Fort Davis before voting for its abandonment, the town and surrounding Davis Mountains would lose the steady funding, prestige, and security that the Army had provided for nearly five decades. [1]

Thrown upon its own resources, the community of Fort Davis spent years weaning itself from the cycle of dependency that military spending created in the American West. The presence of the U.S. Army had opened the land for Anglo settlement. In addition, the purchase of beef, foodstuffs, and services for the officers and men of the fort brought steady wages at national rates; money that the thinly populated Davis Mountains could not have generated internally. The circle of ranchers around Fort Davis, whose economic and political power would grow with the absence of federal authority in the early twentieth century, might not have prospered amid the excellent grazing conditions that the mountains offered: good water, temperate climate (easily twenty to twenty five degrees cooler in summer than the surrounding Texas southern plains), and the black grama grasses that gave nourishment to cattle. Thus the forces of nature that had attracted Indians centuries before worked again to sustain the Anglo population, although the dynamics of power would shift from public to private initiative as the decades of the twentieth century progressed.

T.E. Fehrenbach, longtime historian of Texas, wrote about the meaning of the cattle business to west Texas, and its related impact upon race and class differences in the Lone Star state. "Texas, because of the Civil War," said Fehrenbach, "the interminable frontier, and the problems of the arid western half, was about two generations behind the dominant Northern tier of states in social trends and developments." These conditions of history, economics, and environment created "a tendency for the large cattle ranches of the 1870s and 1880s to consolidate and grow much larger in the next decades." Yet limited access to transportation and communication networks that crisscrossed the nation restricted the pace of change in far west Texas. Given this isolation, said Fehrenbach in his book Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans (1985), "the whole history of Anglo-Texas was a history of conquest of men and soil, and with the closing of the last frontier no such powerful thrust and impetus could merely die." [2]

What separated Texas, especially its rural plains and mountains, from other parts of the nation was the rise of the urban-industrial society on the East Coast and around the Great Lakes. Ironically, refugees from the social and economic problems caused by that shift from farm to city in the late nineteenth-century found in the Davis Mountains a sanctuary from crime, violence, disease, and stress resulting from the rush to develop America's resources. These competing perspectives of agrarian and urban life would persist in the Davis Mountains throughout the twentieth century, even as local interests sought consensus on the creation of the Fort Davis National Historic Site. Had it not been for cities, there would have been no markets for the cattle that Texas ranchers produced. Had it not been for eastern investors, there would have been no capital to purchase land, stock, and hire labor on the great Davis Mountain ranches. Had it not been for wealthy tourists and "lungers [victims of tuberculosis and other respiratory ailments]," there would not have been the sophisticated gentry who promoted preservation of the town and its abandoned military post. And had it not been for the federal government, there would not have been the means to recapture the history of old Fort Davis for future generations to visit and admire.

It is ironic that the story of Fort Davis and its surrounding area has not been told from this angle; a phenomenon that reflects as much the maturing of the history of America (and of Texas) as it does the avoidance or denial of local citizens to delve into their storied past. A statistical analysis of the nation and of Jeff Davis County reveals patterns of economic and ethnic reality that influenced the work of Fort Davis boosters, as well as officials from the National Park Service who came several times into the Davis Mountains to weigh the merits of the area's history. What emerges are the similarities and differences between west Texas and the nation, as evidenced by Fehrenbach's contention that the Lone Star state lagged one-half century behind the country in economic and social evolution.

The last time that the U.S. census bureau sent enumerators to Fort Davis while its military post remained active was the fateful year of 1890, when Frederick Jackson Turner realized that the statistical "frontier" had "closed." The Wisconsin professor wrote that a lack of open and free land would halt the American sweep across the continent; a phenomenon to which he ascribed the nation's sense of democracy and opportunity. Turner's generalizations about this statistic ignored the fact that two-thirds of all people west of the Mississippi River in 1890 lived in communities of 2,500 or more (hardly "rural" by nineteenth century standards), or that only eight million people resided in the entire West. This created the anomaly that historian Gerald D. Nash called an "oasis civilization," which he described as people gathering in large urban centers and avoiding the isolation, distance, and harshness of the rural West. [3]

Numbers mean little without evidence of human interaction and purpose. Yet statistics for Jeff Davis County (created in 1887 out of the vast Presidio County that stretched to the Rio Grande) reveal the scale of land, and the limits of human habitation, that left the Davis Mountains outside Turner's thesis of a "lost" West. In 1890 the county had 1,922 square miles (which would expand by 1930 to 2,263 square miles). Its total population was 1,394 (a density of three-quarters of a person per square mile), of whom 558 were women and 836 were men; a ratio not uncommon in military communities surrounded by ranches (both of which were populated primarily by men). In terms of racial and ethnic backgrounds, Jeff Davis County in 1890 had 37 blacks still remaining, despite the departure five years earlier of the black Army units, which had secured the Davis Mountains for Anglo control. Far more prominent were Hispanics, whom the census had yet to differentiate statistically (this would not occur systematically until 1970). Under the category of "foreign born," Mexico claimed 270 residents of Jeff Davis County, with other countries only in single figures. Native-born Hispanics were identified as "white" for census purposes, although that would not be the social definition in Texas or the Davis Mountains. [4]

Starting in 1900, patterns of change and continuity without the influence of the Army became quite apparent in the census data. The county's population fell 17.5 percent (to 1,150), while the state of Texas grew 36.4 percent (to three million). Nearly all of Jeff Davis County's decline came among "whites" (down from 1,352 in 1890 to 1,107 in 1900). Blacks increased to 43 that year, and more striking was the rate of black literacy. Two-thirds of black adult males were literate in 1900, while only 48 percent of Anglo and Hispanic males could read and write. The overall male-female ratio had also closed by then, with the county having 642 men and 508 women of all ages. Family size had also grown to 4.4 persons, a figure still less than the Texas average of 5.1 members in a statistical family. [5]

What these numbers seemed to reflect was the natural decline of the Davis Mountains population base caused by the closure of the post, along with the stabilization of sex ratios, family size, and balance of ethnic groups brought to the area by military service and support. But the emergence of the cattle kingdom mentioned by Fehrenbach also accelerated in the early twentieth century, as families expanded their acreage and their power in the community. Lucy Miller Jacobsen and Mildred Bloys Nored, authors of Jeff Davis County, Texas (1993), noted how "after 1880, Southerners moved into Jeff Davis County to challenge the northern, Republican, federal influence" created by the fort. "Jobs at Fort Davis became progressively scarce" in the 1890s, as the national economy sank with the Panic of 1893. "Many Hispanic families," said Jacobsen and Nored, "as well as others, moved to Shafter to work in the mines," while railroad construction around Alpine and Marfa drew still more Fort Davis families and individuals. Sealing the fate of many was Mother Nature, which in 1891 brought "an exceedingly dry year followed by a bitter winter." [6]

The same aridity that contributed to what local rancher Clay Miller called in 1995 the "highly cyclical" nature of the west Texas cattle business, provided a haven for urbanites with respiratory illnesses, and also for east Texans who contracted humid-climate diseases like malaria. Jacobsen and Nored spoke of the arrival in the 1890s of "health seekers," whose physicians prescribed the dry air and high altitude of places like Albuquerque and Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Colorado Springs and Denver, Colorado. When these patients and their families came to the Davis Mountains, they found few accommodations for their indefinite recuperation. The grounds of the fort thus became their lodging, where the "lungers" shared space with Hispanic families who could not afford housing in town, and with "expectant mothers [from surrounding ranches who] waited out their terms there with friends or relatives." For a time a recovered tuberculosis patient, William Pruett, built a tent sanitorium five miles north of the fort, and also housed lungers' families in tents east of town. Health care thus created economic opportunity in the Fort Davis area, as did the arrival after 1900 of people whom Jacobsen and Nored called "the wealthy of pre-air conditioned Houston and Galveston [who] discovered Fort Davis as a summer retreat." They built expensive homes with wide, screened porches along Court Street, hired servants from the surrounding area, and created a life that the locals referred to as "Millionaire's Row." [7]

More evidence of this stability in the Fort Davis community came in the late 1880s, when ministers of several Protestant denominations came to the Davis Mountains to preach to the soldiers, their families, and the ranching community. The most prominent of these was Dr. William B. Bloys, born in Tennessee in 1847 and a graduate of the famed Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio. Reverend Bloys and his wife first came to Coleman, Texas, where for nine years he ministered to that rural community. In 1888 he too came to the Davis Mountains for his health, spending 29 years as the representative of the Presbyterian faith in the area. Because he had no church at first, Reverend Bloys used the chapel at the fort, and because he had no congregation he rented a buckboard and rode around town inviting children to Sunday school and adults to the service. Indicative of the multiracial character of Fort Davis was the receptive audience that Bloys found among Hispanics, whom the minister reached through the translations of Robert Fair, a black veteran who remained in town after the departure of the black units and who served as custodian of the post in the early 1890s. Equally important was Bloys' outreach to ranching families with his annual summer campmeeting, which served as much a function of social gathering as it did religious instruction and worship. [8]

It was people like Bloys who set about to change the character of the town of Fort Davis, and to adjust the community to the departure of the military. In a story written in 1963 entitled, "History of the First Presbyterian Church of Fort Davis, Texas," the unidentified author called Fort Davis in the 1880s "a lawless frontier town." Among the forces contributing to "its unsavory reputation" were "the vast distance from centers of civilization," the "general turbulence and disorder of the post-Civil War days," the unruly garrison of Negro soldiers," the "recent arrival of cattlemen and other pioneers, many of them literally a law unto themselves," and most distressing, "the presence of nine wide-open saloons!" The Presbyterian church took credit years later for the "steady and persistent influence" that brought "gradual change to a law-abiding community." By imparting piety and rectitude to the area, the Protestant ministers also changed the social and racial dynamics of Fort Davis, in ways that could be seen statistically and anecdotally by the early twentieth century. [9]

The most dramatic demographic change of the early twentieth century came with the departure of black citizens by the 1920s. Even though Jeff Davis County had fewer than two persons per square mile in 1910, the population had rebounded by 46 percent (to 1,678) There had been a decline of nearly one hundred people from "Precinct 1," which encompassed the town of Fort Davis. Yet the western side of the county (Precinct 4), including the ranching areas and the new railroad center at Valentine, had grown from 62 people in 1900 to 606 a decade later, increasing by a factor of ten. The number of blacks grew slightly from 43 to 47, and were now divided by the census enumerators between the category of "black" (12) and "mulatto," or mixed (35). This made the county four percent black, while the state of Texas was 17.7 percent black that year. Of the foreign born, 292 came from Mexico, and only 15 from Germany (the largest European producer of immigrants). Indicative of the county's deviation from national standards, however, was the statistic on education. Whereas the nation pushed for compulsory attendance under the directions of Progressive reformers like John Dewey, only 44 percent of all school-age children in Jeff Davis County were in attendance in 1910 (by comparison, five of the county's seven black children went to school). [10]

Jeff Davis County changed yet again in the turbulent years of 1910-1920, with the international crisis of World War I creating both opportunities and problems for community maintenance. Farmers and ranchers nationwide were encouraged to "plant from fence to fence for national defense;" a reference to food production for consumption at home and in war-torn Europe. Yet the need for manpower in uniform drew away able-bodied youth everywhere, with many not to return to their rural roots. These factors joined in Jeff Davis County with the outbreak in 1910 of the Mexican Revolution, which was marked by the threat of violence (both real and imagined), and the flight of Mexican citizens northward across the border to seek shelter and employment in American industry and agriculture. This volatility would result in the loss of nearly 12 percent of the county's population (to 1,445) from 1910-1920. Most striking was the departure of blacks, down from 47 to eight (a loss of 87 percent). Illiteracy rates more than doubled from 9.6 percent in 1910 to 20.9 percent in 1920, with white illiteracy at 11.6 percent and foreign born (primarily Hispanic) at 50.8 percent. [11]

Driving this demographic change, and hence the lifestyles of Jeff Davis County residents, was the expansion of large ranches in the Davis Mountains. In 1900 the census bureau had found 48 farms and ranches; in 1910 this had nearly doubled to 91. By 1920 the number had receded by almost one-third, to 62. Thirty-eight of these farms and ranches (over 60 percent) were 1,000 acres or larger, while only ten (16 percent) were 100 acres or less. The average size of these ranches (large and small alike) was 14,958.9 acres, with average dollar value in 1920 at $7.625 million (double 1910's amount of $3.73 million despite fewer farms and ranches). Most revealing of the concentration of power in the hands of large ranchers by 1920 was the total value of cattle: $2.36 million of the $2.42 million (or 98 percent) for all agricultural production in the county. [12]

The decade of the 1920s was marked nationwide by the statistical "victory" of urban areas over the historical dominance of rural America. For the first time since the census was taken in 1790, cities possessed the majority of all residents (52 percent to be exact). The political power of rural legislators was thus in jeopardy, as the U.S. Constitution dictated apportionment of congressional representation based upon percentages of population. Because rural interests did not want to surrender power to their city cousins, they blocked for the only time in history the reapportionment of congressional districts, so that they would not be outvoted in the nation's capital. Other manifestations of the rise of urban America were the car culture, the entertainment industry (especially Hollywood and the movies), and cultural interaction between blacks and whites in American cities (at once accommodationist and separatist with the coming of the "Jazz Age" and the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan).

From 1920-1930, Texas grew at a pace equal to that of the nation (24.9 percent). This decade saw the rise of urban Texas, with all its attractions and temptations. In Jeff Davis County, the pattern was mixed, as the first five years of the "Roaring 20s" witnessed dramatic migration from outside. The accessibility of the county by car, the open space, and the improved national economy led the county to grow overall by 24.6 percent (nearly the state and national average). Precinct 1 (the town of Fort Davis) grew by 200 people (to 912, or 28 percent). For the first time in the census, the federal government in 1930 tried to enumerate Hispanics separately from "whites," calling them "Mexicans;" a term that many would repudiate because of the pejorative use of the word by Anglos in the Southwest, and one which the census bureau would discard thereafter until the 1970 enumeration. Yet because of that momentary usage, Jeff Davis County was found to have 1,046 people of "other races," mostly Mexican, for a total of 58 percent Hispanic, 40 percent white, 1.1 percent black (20 people, of whom 18 lived in Fort Davis), and the rest from other nationalities. [13]

This growth rate, and its concomitant ethnic dimensions, contributed to the rise in illiteracy in the county (up to 30.7 percent from 1920, or an increase of one-third, even faster than the population growth rate as a whole). For native whites, the rate was less than one percent, making nearly the entire increase a function of Hispanic migration. Ten of the fourteen black adults were also illiterate, and nearly all worked in categories of common labor or domestic service. The primary reason for this continued disparity in income and race was the expansion of local ranches, up nearly 30 percent from 1920 (to an average of 18,256 acres). Over 97 percent of all county land (1.784 million acres) was in pasturage in 1930, and nearly 98 percent of that (1.773 million acres) was on ranches of 5,000 acres or more (a doubling of large ranches since 1920). One quirk in the farm and ranch statistics from 1920-1930 was the short-lived attempt of small owners and tenants to gain a foothold in the Davis Mountains. The census bureau analyzed the health of the agricultural economy in mid-decade, and found that the number of county farms and ranches had more than doubled (from 62 to 128), with farm/ranch size shrinking seven percent (to 13,484 acres). Total farm value grew by more than a factor of three in those five years (from $5. 161 million to $16.778 million), with the average farm or ranch in Jeff Davis County in 1925 worth nearly 60 percent more than 1920 ($131,079). [14]

The prosperity of the Twenties did not continue, either nationally or in the Davis Mountains, as the collapse in 1929 of the New York stock market resonated throughout the economy in the desperate years of the Great Depression (the 1930s). Across the country, the value of agricultural production fell over 50 percent, stock prices dropped nearly 90 percent, and by the winter of 1932-1933 the adult unemployed population stood at 33 percent (with an additional 33 percent listed as "underemployed" with fewer hours, wages, or both). Jeff Davis County would suffer along with the rest of America in these years, although the population data was not as conclusive. The 1940 census report found 2,375 people in the county, up nearly 32 percent, and the density finally broke the county's one person per square mile (still half of Turner's "frontier" diagnosis of two generations earlier). The town of Fort Davis fell from 912 people to 537 (over 40 percent), while the northeastern quadrant of the county grew by a factor of six (from 106 to 652). Precinct 3 (the southeastern county) grew from 57 in 1930 to 481 (900 percent), and the growth in far west Jeff Davis County led to incorporation in 1936 of the town of Valentine (499 people, or nearly 92 percent that of Fort Davis). [15]

Population movement seemed to reflect the ability of the large ranchers to maintain their levels of employment, even though the value of their holdings (land and stock) dropped along with the national totals. The value of cattle in the county fell over 60 percent (to $1.8 million), and all stock declined nearly 40 percent (to $2.257 million), even as the number of farms and ranches grew slightly (from 99 in 1930 to 104 in 1940). One indicator of the meaning of this change was the collapse of the modest fruit and vegetable production of Jeff Davis County: down to a mere $20,250 in 1940 (from $52,676, or a decline of 64 percent). There were in 1939 a total of 25 farms and ranches that sold or traded less than $250, while there were 23 ranches that sold/traded over $20,000 each. The 22 poorest farms and ranches did a mere $2,514 in business combined, while the 30 richest ranches transacted $ 1.424 million in 1939, for an average of $47,000 per ranch. By comparison, the national minimum wage for hourly labor was 25 cents, and the per capita income for all Americans in 1933 was $400. Thus the poorest quarter of Jeff Davis County farms and ranches produced less than three-fifths of the national average for income, while the wealthiest third produced on average 420 times that amount. [16]

The disparity of wealth and poverty plaguing Jeff Davis County in the years between the first and second World Wars explained in part the federal government's belief that it had a duty to redress the economic grievances of the Great Depression. Until 1920, most Americans had encountered government primarily through postal clerks, law enforcement officers, and perhaps military service. T.E. Fehrenbach noted how that war had destabilized the urban and farming sectors of the Lone Star state, and how advances in technology (especially the automobile) transformed the landscape. "Texas went from a horse culture to something resembling an automobile culture in one swoop, " said Fehrenbach, as "roads hastened economic improvements, urbanization, and school consolidation in almost every region of the state." This process of urbanization (Texas by 1933 was 67 percent rural, closing the gap with the national pattern of 41 percent rural population),"began to drain off some of the misery from the cotton fields." Then the twin ravages of economic collapse and the environmental disaster of the "Dust Bowl," where the southern Plains lost much of their topsoil to winds and the overplowing of new land, created the diaspora from the region to California and the Far West more heralded in John Steinbeck's novel about "Okies" on the "Route 66," The Grapes of Wrath (1939). [17]

Local residents of Fort Davis could not have predicted these conditions when in 1910 they hosted their annual Independence Day celebration. On that Fourth of July, the parade boasted no fewer than 25 automobiles, even though there were no paved roads into the Davis Mountains. The state would not build a highway yard in the county until after World War I, prompted by passage in 1916 of the Federal Highway Act, whereby the U.S. government would construct a series of paved roads across the country to expedite commercial and military travel. This did not deter the creation also in 1910 of the Fort Davis "Improvement Club," whose duty it was to promote economic development in the region. Its literature, and that of the Fort Davis Dispatch (begun in 1911), mentioned prominently the environmental pleasantness of the Davis Mountains, especially drawing attention to the 5,000-feet altitude of the town. [18]

Dramatizing the prospects of a western town was not a new idea, as communities like Los Angeles had grown exponentially in the early twentieth century through a combination of transportation, communications, climate, and advertising. Fort Davis, like its peers throughout the West, hoped that growth could create new jobs, promote land sales, and improve the quality of life in an isolated region. This urge to advertise one's way to economic health had its parallels in the Davis Mountains with the appearance of Carlysle G. Raht, who had visited the area with his father in the summers when he was young. Raht moved to Fort Davis in 1916, determined as a graduate of the University of Texas to write a dramatic story of the "old" West like he had heard from his professors in history. The Austin school in the early twentieth century had become a center for regional study, among whose graduates were J. Frank Dobie, the noted folklorist of tall tales and legends of the Southwest; Herbert Eugene Bolton, a Wisconsin native who admired the stories of Spanish occupation of the area, and who at the University of California would create the "Borderlands thesis" of Spanish history; and Walter Prescott Webb, best known for his pathbreaking study The Great Plains (1931), written in the depths of the Depression and the start of the Dust Bowl about the struggle of farmers and ranchers to control the environment of the West. Raht wanted to find his version of all three stories (folklore, Spanish conquest, and cowboy culture) in the Davis Mountains, and his efforts went far to demonstrate to outsiders the distinctiveness of the area, if not their actual history and tradition.

Raht's endeavors were aided by the research of a young reporter named Barry Scobee, whom Raht had met by chance in 1917 in the newsroom of the San Antonio Express. Scobee, who had grown up on a Missouri farm dreaming of writing history, asked Raht if he could make a living in the Davis Mountains about which Raht spoke so glowingly. Scobee was described in later years as a "mild-spoken little fellow with a bald head, a good heart, and a sincere likeable character that charmed everyone." Upon his return to Fort Davis, Raht corresponded with Scobee, offering him the opportunity to manage the Hotel Limpia, opened in 1912 to serve the wealthy summer visitors to the area. The constraints of wartime limited the Limpia's income, and by extension Scobee's, and he and his wife Katherine survived only because Raht hired the former reporter to "travel over the area with him in an old flivver to gather material for his book." Scobee volunteered for service in World War I, only to report to basic training as the war ended in Europe. He and his wife left the Davis Mountains for opportunities in the Pacific Northwest, and returned in 1925 with the intention of selling stories to popular magazines about the glamour and drama of the old Southwest. [19]

The book that Raht and Scobee compiled fit the pattern of excitement and action that gripped audiences' imaginations in the post-World War I era. It also served as the history text for many local residents and visitors, who were fascinated with Raht's stories of derring-do, conquest, outlaws, bandits, and the like. Raht furthered the importance of his work by claiming in the preface: "In gathering my data I have attempted to eliminate the personal viewpoint of the narrator, as well as of myself." He declared that he had "written out of sheer love of the country and a great admiration and respect for the hardy pioneers who had conquered it." Adding to the book's "authenticity," and perhaps its historical irony, was Raht's acquisition of historical documents on the Spanish era (1540-1821) from the "Archivo General Nacional," or National Archives in Mexico City. He then asked Henry O. Flipper, the young black lieutenant court-martialled at Fort Davis in 1881 and now a mining engineer in El Paso, to translate the Spanish documents. [20]

Raht proceeded to describe Hispanic Texas in the most derogatory terms imaginable. In so doing he merely echoed the sentiments of the day among Anglo Texans, and reinforced local opinion on the inferiority of Hispanics (all of whom were called "Mexicans," even if they were natives of the United States and were considered "white" for census purposes). He also highlighted the class differences of Jeff Davis County by calling the great ranchers "a people who have never felt the cramping littleness of more thickly settled communities." Raht concluded that the ranchers were "literally 'monarchs of all they survey, "'ignoring their own dependence upon eastern markets, investors, technology, and also low-paid wage labor provided by Hispanics. [21]

What made Raht's negative characterization of Hispanics even more important was their "majority-minority" status in town and throughout west Texas. T.E. Fehrenbach wrote that "the Texan attitude toward Hispanic Americans, born out of long and unhappy experience with Mexico, was not essentially hostile; it was rather one of considered domination." After 1900 the Anglo power structure in Texas encouraged blacks to migrate elsewhere, and replaced their work with Mexicans because "the cost of land, irrigation, and crushing freight charges could only be met by using labor cheaper than any other in the United States." These economic imperatives, coupled with the political control that west Texas ranchers had in their communities, meant that "every major social change that came in the twentieth century was forced upon the state of Texas by outside pressures." [22]

Readers of The Romance of Davis Mountains and Big Bend Country thus encountered well-known images of noble Spaniards, free-market cattlemen, and Mexicans whose only place was subservient to the Texas master class. What reinforced Raht's rhetorical style was the banditry of the Southwestern border, popularized in March 1916 by the raid of the Mexican revolutionary Francisco "Pancho" Villa on Columbus, New Mexico, a small border town west of El Paso. Raht emphasized the violence and retaliation on the part of American forces (both Texas Rangers and U.S. Army), which brought wartime conditions to the border that contrasted with the relative tranquility experienced throughout World War I by other parts of the country.

Ignoring the contributions that Hispanics had made to the ranching economy of the region, not to mention the intermarriage of prominent Anglo ranchers and Hispanic women, Raht told his readers: "More often than not the good little blood the peon [Mexican] may have in his veins is contaminated with disease, and, from the mother stock, he rightfully inherits the bloodthirstiness of his Indian forebears." Raht further believed that the Hispanic, "like the Indian, is constitutionally opposed to labor." Referring to the stereotype of the Mexican peasant, Raht declared: "So fixed has become the habit of obtaining a livelihood without work and so in keeping with their natural tendencies, that it is doubtful whether our Southern border will ever be safe, except it be by force of arms." Then in a disjointed conclusion, Raht (whose knowledge of the area extended only to his childhood visits and study at Austin) informed his readers:

"Despite all these obstacles, the West-of-the-Pecos country has grown and prospered. Nowhere in the world will be found a higher type of citizenship . . . . The final settlement of the troubles in Mexico and along the border will insure the future of this great country." [23]

Raht's judgments, which he crafted in his journeys through the Davis Mountains with Barry Scobee, emanated from the stories told to him by the Anglo ranchers and citizens of Fort Davis. Confirming Raht's viewpoint was the segregation of the races in the Fort Davis area; part of the effort of Anglo townspeople to present a homogeneous face to the outside world of investors, tourists, and potential residents. Jacobsen and Nored wrote of earlier racial divisions in town: "There are stories of bodies, mostly children, along the east slope of Sleeping Lion [Mountain]. This area was probably cluttered during the 1870s with the shacks of the families or camp followers of the black soldiers[,] and babies and children who died were simply buried behind the hovels where their parents lived." A "colored school" operated in town from 1888-1895, and Hispanics who did attend school were routed towards the "Mexican school" on the north side of town (the current site of the Dirks-Anderson elementary school just south of the park boundary). White children, by comparison, went to the "American" school on the south side of town (the site of the modern-day Fort Davis High School). [24]

In the early 1900s, Texas state laws separating students by race were applied throughout the town, and children of "mixed blood" (primarily black and Hispanic) were sent to the "Mexican" school. The legacy of this segregation, said Jacobsen and Nored, was that "after adoption of these new rules, the number of Hispanic children enrolled in school dropped dramatically. Until the late 1920s, education opportunities for Hispanics in Fort Davis [were] minimal at best," with the first Hispanic graduate of Fort Davis High School (Tommy Morales) receiving a diploma in 1939 (this in a county that had been predominantly Hispanic from its inception). The first chief of maintenance at Fort Davis National Historic Site, Pablo Bencomo, would speak of this inequity in 1995 when he remembered how his father, a ranch hand without education himself, came to the "Mexican" school when Pablo was twelve and removed him from class. "My father told me that there was no more need for me to go to school," said Bencomo, and the young man recalled crying at the cattle ranch because he missed the camaraderie and intellectual challenge of his education, even though it was in a segregated setting (his teacher had been John Prude, from a prominent ranching family, who spoke Spanish to the students). [25]

Just as the ethnic and economic realities of Jeff Davis County crystallized in the mid-twentieth century, the boosterism of the Fort Davis business elite and the romanticization of Carl Raht and Barry Scobee brought travelers to the region in larger numbers that ever before. The need for services, such as lodging, dining, recreation, and entertainment, required a different strategy than that employed by the ranchers, whose goal had been maintenance of their economic well-being in an uncertain and highly competitive world of investment and finance. The tourism business was something new to most parts of the West, and local boosters sought to understand not only the tastes of the visitor, but also the potential of the Davis Mountains to bring in revenue and taxes that would anchor the next generation of economic development. The consumerism of the 1920s created middle-class expectations of access to the same amenities as the wealthy had known prior to World War I. Those individuals and communities that could determine the best strategies for luring and retaining the affluent visitor might benefit in the highly competitive business atmosphere of the Roaring Twenties, while those unable to fathom the "leisure economy" growing amidst a society of hardworking people would suffer.

What distinguished the post-World War I focus upon travel and tourism was not merely the appeal of escape and climate, but also the use of history as a lure. Michael Kammen, author of Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (1991), has written of the surge of interest in the 1920s and 1930s about America's historic past, and of the methods applied by enterprising souls to bring in tourists and visitors seeking connections to the culture and heritage of a nation that until recently had only looked forward for guidance. Kammen linked this new fascination with history to the fact that "during the later nineteenth century . . . Americans of all sorts had to confront a new economic order with a stock of assumptions deeply rooted in preindustrial society." By seeking a more pastoral, agrarian world within the confines of urban-industrial life, Americans would become more nostalgic and sensitive to the past, even if this distorted both the present and the past that gave rise to the history being admired. Americans, like their European counterparts, were unfazed by this contradiction. Kammen thus noted that "another general characteristic that is commonly shared by tradition-oriented cultures, including the United States after 1870, is the use of monuments, architecture, and other works of art as a means of demonstrating a sense of continuity or allegiance to the past." [26]

Three forces thus converged in the Davis Mountains in the interwar years (1920-1940) to advance the story of the region, and by extension the desire of a small group of locals to create a park at old Fort Davis. Providing services to visitors not only generated income and attention. It also brought public spending by the state and federal governments for transportation and communications networks that could increase the ability of the cattle ranchers to compete in the national marketplace. In addition, the declining local economy in the Great Depression could benefit from New Deal social welfare programs that required little contribution from locals (as they did not rely upon property taxes from the county). Finally, the rise of the western myth in film and literature after 1920 solidified a "tradition" in west Texas that made sense to locals, whether on the ranch or in town. Efforts to tell the Davis Mountains story would thus combine plans for publicly funded recreation, highway construction, and private initiatives to graft the national nostalgia for the "old" West onto an area that still echoed the nineteenth century.

Michael Kammen noted the irony of this national mood in the 1920s, saying that the decade "marked a pivotal moment in the self-aware marketing of regional traditions:

rodeos, mock cowboy fights, roped-off business districts, and so on." A second phenomenon of the age was the "determination to democratize tradition" via the automobile. Henry Ford contributed to both movements (modernization and nostalgia) by mass-producing inexpensive cars, then preserving the world that mobility threatened in his "Dearborn Village" outside of Detroit, Michigan. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the son of the Standard Oil magnate most often linked to the Gilded Age's industrial capitalists, or "Robber Barons," likewise invested in the rehabilitation of colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, reproducing the eighteenth century "lost world" of Thomas Jefferson and the founding fathers. Traveling to historic sites became fashionable, and Kammen stated that "some roads were constructed or proposed for the exclusive purpose of facilitating nationalism and tourism." The result of this for America, said Kammen, would be within a generation the "commercialization of tradition and the modernization of national memory." [27]

Residents of the Davis Mountains had not been strangers to national celebrations, with the tradition of the Independence Day festivities dating to the nineteenth-century garrison. Jacobsen and Nored recounted stories of townspeople gathering at the abandoned post hospital, "using the high porch as a table for the tons of food the ladies provided." Hispanic citizens from the nearby neighborhood of Chihuahua came to the post in the late nineteenth century to commemorate the Mexican holidays of "Cinco de Mayo" (Fifth of May), and "Diez y Seis de Septiembre" (Sixteenth of September). The former recalled the 1862 defeat of the invading French army under their leader Maximilian, while the latter marked the end of the Mexican revolution (1810-1821). "There were parades at the old fort," said Jacobsen and Nored, "and one or two seem to have been through the streets of Chihuahua. Bailes [dances] generally followed in the evening." The Anglo population also used the old fort grounds for "community Faster egg hunts," while plays were given in the cottonwood grove east of the fort "to take advantage of the tourist dollar and to offer entertainment to the summer visitors." One such performance, remembered Ellen Yarbro Bailey, was "a Hiawatha pageant . . . probably in the late teens or early 20s." The authors saw nothing inconsistent about this highly romanticized story of Indian life that had been written in nineteenth-century New England by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, presented at a site (Fort Davis) dedicated to the defeat and removal of Indians in west Texas. [28]

These local gatherings were not the sort of historical focus envisioned by the business community of Fort Davis in the years between the world wars. They preferred to emulate the successes of other towns and cities that parlayed private and public funding to enhance their economic well-being. The grounds at Fort Davis had not been a moneymaker for anyone owning them since the departure of the Army, and local boosters wondered how they could utilize this new-found interest in history to their benefit. On December 17, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt had signed an executive order giving roughly 300 acres of the Fort Davis lands to the General Land Office (GLO), the precursor in the Interior department to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Charged with promotion of public land sales to generate revenue for the government, the GLO leased the site to J.L. Jones of Fort Davis until his death in 1907, whereupon local rancher Frank P. Sproul became "custodian" of the site "without pay." He leased four acres to a tenant farmer, and hoped to receive one-third of the crop as payment. [29]

Two years later the GLO sent William B. Douglass, examiner of surveys, to appraise the land at Fort Davis for subdivision and sale to the public. Accompanied by Jacob P. Weatherby, described as "the present County Judge and a successful merchant," and Charles Mulhern, "one of the wealthiest ranchers . . . and a practical farmer (as is also Judge Weatherby)," Douglass elected to carve out of the fort grounds 29 lots of 9.56 acres each, and one lot of 12.83 acres. This land lay to the east of the actual site of the buildings, which Douglass hoped could be used for grazing. The acreage lacked suitable surface or underground water for irrigation, and also had "volcanic gravel . . . under which . . . is a soft limestone." The GLO report conceded that wells could be drilled to a depth of 10-40 feet, allowing agriculture on the properties, but the appraisal described the area as mostly "third rate" and "fourth rate" investments. Douglass believed that the government could expect no more than five to seven dollars per acre. He then described the potential site for prospective buyers, saying that the town had about 600 people, "half of whom are Mexican." Fort Davis had good wagon connections to the railroad at Marfa, as well as daily mail service, "several good stores," and was "reputed to be the healthiest in the state of Texas." [30]

Upon completion of the survey and filing of the notice of sale, the GLO on November 21, 1910, sent James W. Witten to supervise the auction of the thirty lots comprising the "old Fort Davis abandoned military reservation." Witten received bids on twenty-two lots, covering 213.61 acres, and collected checks for a total of $2,272.50. The highest bid for the 9.56-acre parcels was $150, with Mrs. Susan M. Janes, Mr. T.H. Brown, Jr. (who bought two such lots), William J. Ward, and Theodore J. Dumble, all of Fort Davis, acquiring property at this quote. Three Hispanics (Pedro Herrera, Alejandro Olivas, and Jose A. Contreras of Fort Davis) also purchased lots, as did Anton Aggerman, a veteran of duty at the old fort, and Benjamin H. Grierson, Jr. and George M. Grierson, sons of the famed post commander and owners of a local ranch. Only one bidder came from out of town: Allen Mills of Marquez, Texas, who purchased four lots. Wiggins then reported to his superiors in the GLO's Washington headquarters that eight lots remained unsold, and recommended "that no action be taken looking to their reoffering until such time as changed circumstances have created a demand sufficient to justify the expense of further sale." [31]

That moment would not arrive for another 27 years, when in 1937 the GLO divested itself of the eight parcels. By then the status of the land had faded in local people's memory, as in October 1923, R.S. Sproul of Fort Davis wrote to the GLO asking to be made "custodian" of whatever lands remained under federal jurisdiction. This forced the GLO to research its records, and report that only 76.48 acres belonged in the public domain, worth some $720. Because there were no structures standing on the properties, the GLO decided not to accept Sproul's offer, as his "appointment would vest the right in the appointee to use the lands in the said reservation for grazing or other purposes to the exclusion of all others." In addition, the congressional act of July 5, 1884 that governed disbursal of abandoned military lands left no provision for leasing. The GLO was to survey and sell all such lands for no less than $1.25 per acre. William Spry, GLO commissioner, did promise Sproul that the Fort Davis properties would be released when "there is sufficient evidence to show that the lands will be sold." [32]

While the public portion of old Fort Davis appealed only to ranchers, the privately held acreage that contained the facilities abandoned by the U.S. Army faced a different future after World War I. The Army had established in 1917 Camp Marfa, as much for protection against Mexican border raids as for preparation for war in Europe. After the war, the Army renamed the facility Fort D.A. Russell (itself the name of a post near Cheyenne, Wyoming in the nineteenth century), and sent troops marching north on occasion to the old Fort Davis grounds for field training. For the next 20 years the South Texas military posts of Forts Clark, Brown and Bliss also utilized the open space at Fort Davis and the surrounding area. But the most active proposals for the post came from local businessmen in search of the economic stimulus of tourism. As early as 1921, a group of Fort Davis civic officials petitioned the Texas legislature to set aside lands in the Davis Mountains for some sort of state park. The following year a banker from Chicago, Harry G. Hershenson, wrote directly to Arno B. Cammerer, acting director of the National Park Service, to seek federal creation of a Davis Mountains park. Hershenson, who may have been a summer visitor to the area, believed that NPS plans were already underway to include the Davis Mountains in the fledgling national park system. Cammerer wrote in response: "As far as we in the Park Service know, no movement has been set on foot to establish such a Park." The major hurdle facing the Davis Mountains was the fact that "Texas has no nationally owned public lands." Locals would have to purchase the desired property and donate it to the government, as "Congress has never yet made an appropriation for the purpose of buying lands to establish a national park." Cammerer wondered if Hershenson had confused the NPS with the Texas state park system, which now had five units, "each of which is governed by a separate commission." [33]

|

|

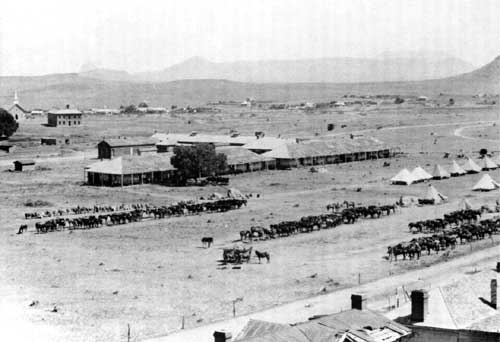

Figure 4. Fort D.A. Russell Maneuvers, A

Fifth Cavalry (c. 1922). Courtesy of Fort Davis NHS. |

Hershenson's inquiry signaled a dual track being pursued by local Fort Davis merchants to bring business to their vicinity. Cammerer' s reply suggesting the involvement of the state of Texas in the Davis Mountains was met in 1923 by a letter from another Chicago businessman, William Havens, secretary/treasurer of the American Motor Freight Company. Writing generically to the "United States Government Bureau of Parks," Havens asked for information "as to the state of Texas and the U.S. Government going to have a National Park near Pecos Texas comprising of 300,000 acres on the foot of the Davis Mountains." Havens told the federal government: "I expect to buy some property out that way and would like to know whether this park is even going to exist." He had learned from local sources that the "state of Texas has made no appropriation for the Park," even though he had been led to believe that both the state and federal governments would purchase the lands in Reeves and Pecos counties for such a park. [34]

Coming so closely on the heels of the Hershenson letter, Haven's correspondence did not indicate to the park service the extent of the promotional campaign by Fort Davis boosters to bring public funding to the Davis Mountains. B.L. Vipond, acting director of the NPS, wrote to Havens a note almost identical to that sent by Cammerer to Hershenson. Then on May 13, 1924, the NPS learned that Representative Claude Hudspeth of Texas had introduced in Congress HR 9193, "A Bill to establish a national park in the state of Texas." This appears to be the first official request to the NPS for such a facility in Texas, and it called upon the Secretary of the Interior "to purchase at least five thousand acres of land in Jeff Davis County . . . to be a national park and dedicated as a public park for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United States." Even as the NPS told Hershenson and Havens that Congress had never considered purchase of private land to create park units, the Hudspeth measure stated:

"That the sum of $100,000 is hereby authorized to be appropriated, out of any moneys in the Treasury of the United States not otherwise appropriated, for the purchase of said land and for other purposes incidental to the creation of said park." Hudspeth did allow for donations of "lands, easements, buildings, and moneys" to the Davis Mountains project, and declared the authority to do so rested in the enabling legislation of 1916 that formed the National Park Service. [35]

Although the Hudspeth proposal died in the House, its existence suggested the problems that the park service would have for the next 35 years in creating an NPS unit in the Davis Mountains. Local promoters did not know of the constraints placed by Congress upon the NPS, yet they would champion park status with visitors who then solicited help on their own. In addition, the local boosters saw more value in the 1920s in preservation of natural beauty than historic property. This fit the pattern of conservationist thinking outlined by historian Alfred Runte in his book, National Parks: The American Experience (1978). Runte coined the phrase, "the worthless lands thesis," to describe the rationale of the NPS for setting aside vast amounts of public land in the West. "The great majority of Americans took pride in the inventiveness and material progress of the nation," said Runte. Thus the need to develop natural resources drove much public policy well into the twentieth century. For that reason, said Runte, "only the high, rugged, spectacular landforms of the West" were considered for inclusion in the NPS system, and "inevitably park boundaries conformed to economic rather than ecological dictates." [36]

Because this strategy relied upon the grandeur of nature to convince private landowners, resource companies, and their legislators to concede private property to the park service, Runte labeled this process "monumentalism." Future parks would be measured against the beauty and scale of such units as Yellowstone in Wyoming, Grand Canyon in Arizona, and Yosemite in California. Early twentieth century efforts at conservation of natural resources (part of the Progressive era's quest for "efficiency and economy" in government and business) required places like the Davis Mountains to demonstrate how parks "could pay dividends to the national purse," instead of merely relying upon aesthetic appeal or romantic charm. One way that smaller parks could be created after World War I was what Runte called the "embrace of the automobile," linked to the "See America First" campaign conducted during the war to encourage wealthy travelers to avoid the dangers of ocean crossing to Europe, and also to spend their money at home. [37]

The Davis Mountain park plan of the 1920s did try to follow the pattern of "monumentalism," which by necessity ignored an historical resource like old Fort Davis. What is interesting about the local boosters' strategy is their awareness of the sentiments in Congress and the state legislature for park programs linked to economic development. The failure of Hudspeth' s park bill would not daunt the Fort Davis merchants, who instead regrouped in 1926 to press the Texas Highway Department to build the "Davis Mountains State Parks Highway." Known locally as the "Scenic Loop," the route would meander some 74 miles west of Fort Davis through the lands of ranchers, permitting them better access to the railroads and markets away from west Texas. The idea took shape in September 1926, when a group of merchants, bankers, and ranchers met in the back room of the Fort Davis State Bank, across the street from the county courthouse. Among the attendees was a summer visitor, State Senator Thomas Love of Dallas, who declared his willingness to sponsor a bill in the legislature to create the highway. This would also generate jobs in the construction trades in the Davis Mountains, as well as monies to purchase ranch lands from private owners. [38]

Part of the impetus in 1926 for the Scenic Loop also came from the outside, as in the words of Jacobsen and Nored, a "slightly eccentric prosperous North Texas banker," William Johnson McDonald, donated upon his death that year over $1 million to the University of Texas to build an astronomical observatory in his name. The university lacked the expertise to design and construct such a facility, and thus contacted the University of Chicago for advice. Its professors suggested the mountains of far West Texas for their clear air, open space, dry climate, and most importantly their lack of city lights to obscure night vision. A loop road out to the potential observatory site sixteen miles northwest of Fort Davis would enhance the attractiveness of the location to the University of Texas, and would also appeal to state legislators concerned about the economic viability of the route. [39]

|

|

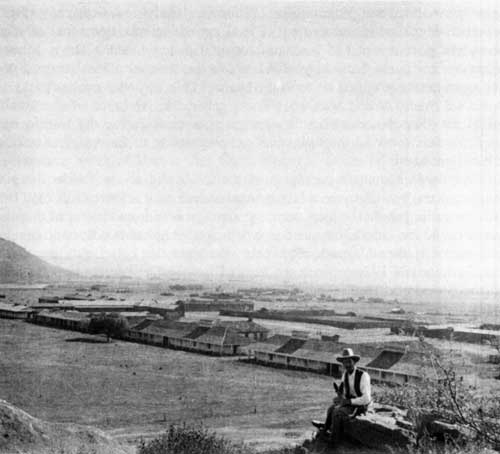

Figure 5. Visitor at Sleeping Lion

Overlook. Note good condition of recently abandoned

structures. Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

As Senator Love's proposal wended its way through the Texas statehouse, local interests cast about for additional evidence of the value of the Scenic Loop. In 1927, the West Texas Historical Association called for preservation of old Fort Davis, but this did not appear in the legislation signed that year by Governor Dan L. Moody to build the highway. Then in 1929 Representative Hudspeth reintroduced in Congress his Davis Mountains national park bill, which again did not include the fort, and which also failed of passage. Resistance to these plans bothered the local interests, as they knew of efforts in Texas and nationwide to accelerate the process of park creation. Michael Kammen noted that in 1927, the state of Virginia, no doubt responding to the plans of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to restore Colonial Williamsburg, "undertook the first large-scale attempt to identify historic sites for motorists." This concept of expanding parks beyond natural beauty to human history found a receptive audience in Austin, and the state legislature followed Virginia's lead in erecting roadside historical markers. [40]

Three events in the late 1920s and early 1930s shifted the focus among local interests from the Davis Mountains to the preservation in town of old Fort Davis. First, the onset of the Depression slowed the pace of state highway construction, exacerbating a condition that the locals may not have realized: the opposition of the highway department to the whole idea of the Scenic Loop. Gene Hendryx, owner after World War II of the only radio station in the area (KVLF in Alpine), and also a state representative for the Davis Mountains in the 1960s, learned when he promoted expansion of the Davis Mountains state park that highway planners had not been consulted on the feasibility of the route, nor had local ranchers been satisfactorily compensated for their lands. In addition, said Jacobsen and Nored, "so many other more heavily traveled routes were begging for improvement." It seems that the local promoters of the road used their political clout in Austin to gain passage and the governor's signature. For that reason the route would take years to complete, with its dedication not held until 1947; 21 years after Barry Scobee wrote a news story about attending the meeting with Senator Love in the Fort Davis State Bank to commence the road project. [41]

Just as the Scenic Loop showed promise, a Hollywood western film star named Jack Hoxie came to Fort Davis with a plan to make the post nationally famous. William K. Everson described Hoxie in A Pictorical History of the Western Film (1969) as "a player of restricted talent and variable pictures," whose "huge popularity must be attributed to the fact that he made more good pictures than bad ones and that when they were good, they were very good." Historians of western film consider the 1920s as the "golden age" of the genre, in that this was the period of rapid expansion of the technology for feature films, and the growth of urban audiences who were neither discriminating in their tastes nor knowledgeable of the accuracy of the story lines. Hoxie, who began his career under the name "Hart" Hoxie (perhaps to link himself to the most prominent western silent film actor, William S. Hart), "was a big, amiable oaf, whose large frame made him seem clumsy afoot and whose expression suggested that his mind was a complete blank." His great gift, however, was his horsemanship, and Everson described Hoxie as "something else again, an expert rider and stunter." Most noted for the film, Don Quicks hot of the Rio Grande, Hoxie impressed audiences nationwide with his "elaborate stunts, leaps, transfers from galloping horse to moving train," while the picture itself benefitted from a series of "majestic exteriors." [42]

When not making movies in the 1920s, Hoxie found employment in Oklahoma on the Miller Brothers "101 Ranch," made famous as a touring Wild West show and working ranch because of its promotion of the era's premier cowboy star, Tom Mix. Hoxie followed in Mix's tradition of athletic ability and presence on a horse, and the owners of the 101 Ranch hoped to find a site for Hoxie to highlight his skills (and also downplay his limitations). This they believed would be in the Davis Mountains, and thus Hoxie was introduced in the spring of 1929 to W.A. Wilson, secretary of the Marfa chamber of commerce. Wilson took Hoxie on a tour of the area, and the Alpine Avalanche reported that the movie star had "'fallen hard' for this environment." Hoxie and his entourage then drafted plans for a $250,000 resort and movie set to be housed at the fort, including "a half mile race track, a polo field, golf course, baseball diamond, a big swimming pool and a rodeo arena." The entire square mile comprising the John James estate's lands would be surrounded by a 55-inch wire fence, and a spokesman told the Alpine paper: "In repairing the old adobe structures and corrals the old outlines will be strictly preserved." [43]

|

|

Figure 6. Jack Hoxie (on right) and friends

at Fort Davis (1930). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

For the next two years, the Hoxie company entranced Fort Davis and environs as only Hollywood can do. In May 1930, J.E. Pierce, president of the New York-based "Pacific Far West Pictures Corporation," came to "Hoxie's Stockade," as the post had become known, to discuss "the possibilities of old Fort Davis as a tourist resort and a place to make 'western' pictures." Speaking for Hoxie was W.A. Wilson, who had convinced three Fort Davis men (Lee Glasscock, Frank Jones, and Herbert Bloys) to sign a 25-year lease with the James family to use the fort. The lessees agreed to give the James estate $300 upon signing, another $300 after one year, $800 within two years, and $1,200 per year for the remainder of the agreement. In addition to this payment of $2,600, Messrs. Glasscock, Jones and Bloys would pay taxes and assessment fees on the property. Soon thereafter the three men received from Frank L. Sproul a 20-year lease on farm land north of the fort along Limpia Creek for an additional $7,000. They then subleased a portion of these properties to Hoxie and Wilson. [44]

Unfortunately for the local investors, the Hoxie company never could develop the property as advertised. The only major event staged at the post was a rodeo in March 1930, witnessed by over 2,000 people on a windy, blustery Sunday. The highlight of the day was Hoxie performing tricks on his famous white horse, Scout, and with his "trained dog Bunk." Hoxie's "leading lady," Miss Dixie Starr, also pleased the crowd with her performance "in a little melodrama wherein the Bunk came to the rescue," and with her "work with the rifle." Visitors sought more news of completion of the project, and one Sunday in March 1930 some 450 automobiles drove through the old fort grounds. One interesting note from the construction work in rehabilitating the ruins came when carpenters found along Officers' Row stone arrowheads embedded in the roofs, leading Barry Scobee to report in the Alpine Avalanche: "Indians used to lie in the rocks above the old fort and shoot arrows down at the soldiers according to local history and evidently there is something to it." [45]

Whether or not there was "something" to the local lore about Indian attacks on the post, the Depression and Hoxie's fading appeal did harm to the town's dream of Hollywood glitter and fame. Jacobsen and Nored (the latter a relative of investor Herbert Bloys) wrote years later that "by spring of 1931, Hoxie' s financial backers were in serious trouble themselves from the drop in oil prices." The cowboy star, in the authors' words, "conned numerous Fort Davis citizens into investing $100 [each] in his enterprise," and none "received a penny of their money back." Jacobsen and Nored then recounted local folklore about Hoxie's shortcomings as an actor; features blissfully ignored when the company was in town. Film historians echoed their criticism, albeit more tactfully. "Hoxie could neither read nor write," said Everson, "and genially accepted some rather cruel inside jokes about those failings in several of his films." The advent of sound pictures by the early 1930s rendered Hoxie useless in Hollywood, as he could not "read, remember, or deliver a line." He thus "drifted out of the movies" as quickly as he had hit Fort Davis with his dream of Hollywood on the Limpia. [46]

With the town of Fort Davis sadder but wiser as a result of the Hoxie affair, civic officials faced the third factor of change in their efforts to promote the Davis Mountains. Where highways and movies had failed, they hoped to take advantage of a new direction in the state and federal government towards parks and history. The administration of Herbert Hoover (1929-1933), noted in history books for its disastrous management of the nation's economy during the Great Depression, nonetheless seemed favorable to expansion of the nation's system of parks and monuments. Hoover and his Interior secretary, Ray Lyman Wilbur, applied liberally the Antiquities Act of 1906, which permitted the executive branch to set aside "man—made wonders or scientific curiosities" for preservation. Vance Prather of Fort Thomas, Kentucky, had written in March 1930 to Horace M. Albright, director of the NPS, about the need for a national park in west Texas. Among his suggestions were the future Guadalupe Mountain National Park near Carlsbad Caverns, Palo Duro Canyon near Amarillo, and "the Davis Mountain area, a mile high, near Fort Davis, an enchanting vista." What made this area appealing, said Prather, was "its vast road system, its easy access by way of the Bankhead, Old Spanish Trail, Glacier-to-Gulf, and other roads." Albright agreed to include Prather' s list in the upcoming NPS studies of new parks, calling it "very interesting and valuable to us." [47]

The defeat of Hoover in the 1932 presidential election did not daunt the boosters of Fort Davis, in that the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt promised even more aggressive action on behalf of the park service. "Whereas Hoover's ventures into history were non-political and bland," said Michael Kammen, "FDR' s uses of the past were shrewd and self serving." The desperate times facing the American people led Roosevelt to experiment with all manner of "New Deal" social and economic programs; what Kammen called FDR's "distinctive capacity to connect innovation with tradition." The 1930s also witnessed a breakdown of resistance to public support of historical institutions. "Had there not been a Great Depression," said Kammen, "it might have taken considerably longer for government at any level to concern itself with American history, myths, and museums." Roosevelt knew that "American society increasingly needed and sought a meaningful sense of its heritage in crisis times," and "since Americans disagreed about numerous policy issues during the 1930s, history seemed a kind of neutral ground." [48]

|

|

Figure 7. Abandoned Fort Davis looking

north from Sleeping Lion Mountain (early 1900s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

The New Deal could come none too soon for boosters of Fort Davis or the Davis Mountains as national parks. On the last day of the Hoover administration (January 19, 1933), Horace Albright signed a recommendation drafted by Conrad Wirth of the Washington NPS office (abbreviated as WASO) to remove the Davis Mountains area from further consideration. Wirth wrote that the Texas state parks board had recently acquired 3,500 acres of land in the mountains along the route for the Scenic Loop. "The road is now being constructed," Wirth told Albright, "and the area is practically established as a State Park." A new presidential administration inspired local interests to resubmit their request, and the park service sent to the Davis Mountains the former superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park, Roger V. Toll, who had become an expert in surveying the potential of new park sites. Toll visited the Davis Mountains in the spring of 1934, and praised the area for its "rolling hills . . . excellent grazing grass . . . [and] numerous outcrops of granite." Unfortunately, the Davis Mountains did not compare to scenery such as Toll had managed in Colorado, and he concluded that the area had "pastoral beauty, but it is not spectacular." Toll suggested instead: "The area is more suitable for a state park than for a national reservation, and it is recommended that it be dropped from the list of proposed projects, but that cooperation with the State Parks Board be continued." [49]

That "cooperation" of which Wirth (a future NPS director) spoke came in the form of park service-supervised construction work at the Davis Mountains State Park, three miles northwest of Fort Davis on the road to the proposed site of the McDonald Observatory. Through a combination of state purchase and leasing of private lands, 2,130 acres of the Davis Mountains were targeted for a resort complex. Its salient feature was "the magnificent mountain setting," said a park service press release in August 1937, "which particularly is attractive to Texans, due to the fact that during July and August it is cool and green, while most of the state is hot and dry." The release said nothing about the ability of the mass of Texans in urban and rural areas to the east to gain access to a publicly funded resort, whose "most outstanding structure is the adobe Indian Lodge, which is an impressive Pueblo style, with sixteen guest rooms each with private baths." The lodge was "furnished throughout with Indian motif furniture made from native woods by the Civilian Conservation Corps [CCC]," and it came complete with "a spacious lobby with dance floor." The Scenic Loop and "several miles of foot and horse trails [made] the mountain scenery more accessible." [50]

While students of the post-New Deal era might note the irony of social welfare agencies like the CCC building such a luxurious facility, the NPS found itself besieged by local interests to hurry the construction and add more touches that would make the resort even more appealing. The CCC is better known to historians as one of the most popular of federal agencies created in the heady "First One Hundred Days" of the Roosevelt administration (March-June 1933). As its goal, the CCC sought the removal of young single males from the streets of America's urban centers, where idleness and lack of employment bred social problems and violence. Its 600 camps were located in rural and wilderness areas of the country, where they were managed by officers of the U.S. Army. CCC enrollees earned $30 per month, which included $10 to be placed in savings, $10 sent home to help with family expenses, $5 per month for room and board, and $5 for spending money. Youth learned discipline, work habits, and job skills in the camps, while the Army provided schooling in trades and mechanics. The NPS in turn offered planning and design capabilities for structures in nature; hence the park service's entry in the 1930s into the Davis Mountains.

As the CCC work unfolded in west Texas, the NPS learned lessons about the political and economic power of the Jeff Davis County elite. One dimension that Jacobsen and Nored recounted was the eagerness of Hispanic youth to seek work on the Scenic Loop crews and at the CCC camp. They especially appreciated the higher wage scales (the NPS paid the national minimum wage of 25 cents per hour), the job training in construction, carpentry, and mechanics, and the opportunity to learn the English language; all skills that might lead to a better standard of living than currently available on local ranches. Less appealing to the park service were the expectations of the locals for inclusion of "extras" like a man-made lake. Harry L. Dunham, district inspector for the ECW (Emergency Conservation Work) program, which included the CCC, wrote to Herbert Maier in the Denver offices of the NPS in February 1934: "There has been an insistent demand by the natives of the Fort Davis District that they be provided with a lake." They claimed that the state and federal officials who negotiated the agreement to build the Davis Mountains state park had included such a lake, and "they expressed a great deal of disappointment that this promise has not been fulfilled, although they donated land for the park on the strength of this promise." Dunham agreed that construction of a dam at the Indian Lodge "will add greatly to the value of the property," as it was "very fine game country." But the lack of proximity to clay deposits would require construction of "either a masonry or a concrete dam; either one of which will be extremely expensive in time and material." Yet he believed the NPS should promote such an expenditure, given that the Davis Mountains "could very easily be one of the out-standing Texas Parks, ranking closely with Palo Duro and Bastrop, and probably next to the Chisos Mountains [the future Big Bend National Park]." [51]

Maier agreed with Dunham's analysis of the potential of the Davis Mountains, and wrote to Conrad Wirth, now director of the NPS "Office of Buildings and Reservations," that "this is without question one of our best state projects in Texas." The Colorado official wanted not only to start the Indian Lodge dam at once, but to experiment with a "two or three shift" schedule to improve employee performance. "It is much better for the morale of the men if the work and the camp is humming," said Maier, "and when especially they can see themselves getting someplace, than is the case where these large projects are forced to move along so slowly." The Washington office, however, did not add CCC monies to Davis Mountain for a dam, and thus Maier and R.O. Whiteaker, chief engineer of the NPS State Park Division in Austin, had to reassess the work schedule for the site. Whiteaker suggested that in order to keep the camp occupied, "it is desired to construct one look-out house on top of a high mountain, reached by trails already constructed and over-looking the town of Fort Davis, Keesey Canyon and the Indian Village," the future connecting trail between the park service site in town and the state park. To compensate for the lack of a large dam, Whiteaker called instead for two small dams in front of the Indian Lodge. The total cost of this expanded work would be $2,360.00, which could employ the crew for 1,400 "man-months" (the amount of time per worker needed to complete the job). [52]

The expectations of the locals were met and exceeded by the demands of Texas state officials, who taught the park service lessons about regional politics that would affect later decisions about the inclusion of Fort Davis in the park system. D.E. Colp, chairman of the state parks board, wondered why the NPS would need 12 months of money for a dam at Indian Lodge, when the state believed that it could do so in 30 to 60 days. "I think there should be 25 or 30 dams built in the Big Bend project," said Colp, and he rejected the idea that it was Texas' fault for the design problems. Colp pleaded with Maier to push for more money so that Texas had "an opportunity to demonstrate to you and the NPS that a large dam can be built at a reasonable cost and reasonable time." George Nason, district inspector for the Oklahoma City-based NPS State Parks Division, disagreed, telling Herbert Maier (now also in Oklahoma City) that "the Lodge at Fort Davis was a larger project than should have been attempted." Nason claimed that "it was started under the control of the Texas Relief Commission at time when the approval of a [park service] District Officer was not required to start a building." Nason suggested that the NPS agree to continue the Indian Lodge camp for another 90-day period, and learn from the fact that "this is simply one of the holdovers from the super-ambitions of the first period of CCC." [53]

The more that Herbert Maier contemplated the costs of completing the work at Indian Lodge, the more he wished to be rid of the task. Writing on January 31, 1935, to his superiors in the ECW office in Washington, the regional office director defined the park as "another case of unreliable estimates in Texas." The Texas state parks board seemed to have "[i]nspectors [who] are not trained as building contractors," while materials purchases were billed to the wrong accounts. The NPS thus had no funds to complete the light plant, painting of the stucco and interior plastered walls, and the "painting or staining [of] all interior and exterior wood work." The extensive flagstone terracing also would have to come from a quarry 17 miles away. "We are exceedingly anxious to get finished at Fort Davis and get out," Maier reported, and concluded: "We certainly know now what is beyond our scope and of course this sort of thing cannot occur in the future under the new method of submitting individual projects." [54]

New accountability procedures notwithstanding, the park service had to salvage what it could at the Indian Lodge before the removal of the CCC camp in the spring of 1935. George Nason decided to convert the garage at the site into an employees' dormitory, which Herbert Maier agreed was necessary, saying: "It most certainly spoils the general appearance of a park to have trucks and old cars standing around with no place to house them." Despite the presence of two hundred laborers, the NPS had not been able to complete a road around the lodge, and the flagstone would have to be laid by "a transient camp or some sort of an FERA [Federal Emergency Relief Administration] project at this point." Nason agreed, and tried at first to put a positive spin on the closure of the camp. "I feel quite confident," he told Maier on February 13, 1935, "that while you may find some error in detail in the solution of the Indian Lodge problem, yet when completed, it is going to be one of the most effective things we have done in a structure so far in Texas." Unfortunately, Nason did not maintain this optimism as the date for camp removal arrived, reporting to Maier on March 23: "I am writing this letter so that you might be relieved to know that this white elephant is practically ready for burial." [55]