|

Fort Davis

A Special Place, A Sacred Trust: Preserving the Fort Davis Story |

|

Chapter Three:

The New West Meets the Old: Creating Fort Davis National Historic Site, 1941-1961

While the Second World War redefined America in a thousand ways, the relationship between public initiative and private power in the Davis Mountains remained constant. From 1941-1960, local interest committed to creation of a national park at Fort Davis attempted to identify the financial means to acquire the post property and preserve its story. In addition, the local economy failed to expand with that of the nation as a whole, leaving the youth of Fort Davis little choice but to seek their futures elsewhere. What did change were political attitudes in the Texas congressional delegation, national sentiment for historic preservation, and the decision by the National Park Service after World War II to examine more closely the significance of the Davis Mountains' abandoned military post. Yet it would require a serendipitous sequence of political events to bring Barry Scobee's dream to life, and even then local boosters would wonder at times what exactly they had accomplished.

Economically, World War II revitalized the United States as Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal social welfare programs had not. Gerald D. Nash wrote in World War II and the West: Reshaping the Economy (1991) about the stunning federal investment in military hardware, uniformed personnel, and support services from 1941-1945. Whereas the nation had faced in 1933 an unemployment rate of nearly one-third of the adult work force, by 1939 that statistic still hovered around 20 percent; this despite federal spending on such programs as the park service's CCC camps and the creation of new parks. Yet the imperatives of national security, coupled with the costs of a "high-tech" war against the Axis powers (Germany and Japan), led FDR to spend some $260 billion to prosecute the Allied effort. This translated into lavish expenditures in urban and rural areas of the country for military installations, defense plants, and the like. By 1945 southern California, for example, had garnered $45 billion of that amount, with smaller percentages going to other cities on the East and West Coasts, the Great Lakes, and the desert Southwest. Unemployment as a result of this federal investment dropped to a statistically insignificant one percent, and postwar planning attempted to maintain both that prosperity and the source of funding that had made it possible. [1]

In the years after the war, the nation's economy would pursue a mixture of public and private spending linked to military preparedness called the "Cold War" (the struggle between American democracy and Russian Communism), and the consumerism triggered first by pent-up demand for goods and services, then by the staggering population growth known as the "Baby Boom." Landon Jones wrote in Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation (1980) about the linkage between growing families in the postwar years, their increased standard of living, and the quest for comfort and security that included tourism and eventually settlement in the "Sunbelt" region of the South and West. Cities became places to earn a living, while the suburbs attracted the housing of these new families. They in turn sought escape from both settings in tourism and recreation, creating the statistic in 1954 that one American in three would visit a national park that year; up from merely one in sixteen at the beginning of the park system four decades earlier. Hitting the road, seeing America's wonders, and absorbing the complexity of the nation's past became goals for millions of citizens, and every town with some natural or historical attraction engaged in the quest for visitor dollars as well as conventional economic expansion. [2]

This shift of emphasis to mobility and leisure should have eased the path of supporters of park status for Fort Davis. So too should have been the essential conservatism of the nation from 1941-1960. Michael Kammen noted how the shared purpose of the war, plus the economic "miracle" stimulated by so vast a program of federal spending for national security, forced promoters of New Deal historical and cultural programs to reassess their themes. "If cultural relativism implied moral relativism," said Kammen of the more controversial New Deal agencies, "both would have to be discarded in favor of a traditionally defined idealism." Then after 1945, "older and individualized crafts looked attractive in an age of standardization. The calm of rustic museum villages looked desirable in an age of intense bustle." From this Kammen recognized yet another series of competing emotional forces at work on American historical memory: "The common denominators in postwar statements of mission stressed their educational objectives and their desire to preserve oases of the pastoral, pre-industrial past at a time of startling technological change." [3]

As it had prior to 1945, Jeff Davis County did not move in the directions of the rest of America in the postwar era. Pablo Bencomo and his peers from Fort Davis left town for service in the nation's armed forces, traveling the world and learning of the opportunities, and in Pablo's case, the freedoms awaiting people of all colors and classes elsewhere in the United States. Within the county, opportunity shrank as the fledgling tourism industry, cultivated so assiduously by the Mile High Club and funded by public revenues, collapsed with travel restrictions and the movement of young men and women into uniform or defense industries far away. Jacobsen and Nored recounted how the Davis Mountains State Park's Indian Lodge was forced to close for lack of patrons, only to reopen when "wives of cadets stationed at the Marfa Air Base were housed [there] after literally all available housing was utilized." Without visitors, federal programs, or donors willing to fund park creation, Fort Davis endured the war with little hope of tempering the forces that for a generation had limited its options. [4]

Statistics for the years 1941-1960 reinforce this cycle of isolation and decline for Jeff Davis County; conditions that the park service commented upon at length when asked in 1953 and 1960 to study the feasibility of a park at the abandoned post. The county's population fell in 1950 by 12 percent from the prewar census (from 2,375 to 2,090). This pattern became more evident when the four voting precincts were counted. Precinct l (the town of Fort Davis) had grown 14 percent (from 537 to 623); yet the village remained 32 percent smaller than it had been in 1930. Precinct 2 (the northeastern quadrant of the county) had dropped the most in ten years, from 652 people to 450 (off 31 percent), and Precinct 3 in the southeast declined 24 percent (from 481 to 368). Even Precinct 4, southwest of town and site of the "Valentine boom" of 1930-1940, lost population by eight percent. [5]

What these numbers meant for social and economic conditions in wartime Jeff Davis County was validation of Jacobsen and Nored's comment that "many youngsters moved away to find work elsewhere." The median income for the county in the 1940s was $1,773, or 78 percent of the Texas average. Fifty-four percent of all county families earned less than $2,000, itself an amount one-sixth below the state standard. Educational achievement for county adults in 1950 was a mere 7.8 years. This may explain the fact that 47 percent of all adults employed in the county in 1950 were classified as farm laborers. In matters of race, the census that year still counted Hispanics as "whites," but the black population had grown from 18 in 1940 to 26 in 1950; an increase of 31 percent, and a number of blacks greater than had resided in the county for a generation. [6]

By 1960 the statistical profile of Jeff Davis County had changed little, even as the successful movement for creation of Fort Davis National Historic Site got underway. The population base fell again by 24.3 percent; down from 2,090 in 1950 to 1,582 a decade later, the lowest number in 40 years. Population density slipped to 0.7 per square mile, against a national average in 1960 of over 30 people per square mile. These numbers translated into a depressing loss of 16.2 percent of all families in the "family-conscious" era of the Fifties. Unemployment numbers were also included for the first time in general county census data, and Jeff Davis County had 10 percent of its adults out of work. Education had not improved at all in ten years, again leveling at 7.8 years per adult. This statistic is striking in comparison to the national emphasis on schooling, triggered in the late 1950s by the Russian space launch "Sputnik," the baby boom, and the advancing complexity of the marketplace. The average American adult had by the year 1959 a 12th grade education, rendering Jeff Davis County some 35 percent below the nation's standard of learning. This also translated to median income , at $3,877 in 1960 only 79 percent of the Texas average ($4,884). More than one worker in three earned less than $3,000 (or $1.50 per hour, when the minimum wage was $1.25 per hour), which meant that 34.5 percent of Jeff Davis County workers received but 61 percent of the Texas median income. Finally, this pattern of decline affected the black population of the county. Census enumerators in 1960 could find only one black resident in Jeff Davis County (a loss of 96 percent since 1950). This may explain in part the confusion in the minds of local residents when the NPS historians sent to Fort Davis not only discovered in the federal records the importance of the black units to the post's history. This was manifest, in the words of Southwest Region historian Robert M. Utley, when county residents referred to the U.S. Army regulars as "nigger soldiers," even as they revered the white officers in command. [7]

In spite of these conditions, the Mile High Club kept to its goal of park status for Fort Davis; a dream that they hoped would come true in 1945 when local rancher Mac Sproul purchased for $16,000 the 640-acre site of the old military post. This was half the amount that the club had asked of the Texas Centennial Commission a decade earlier, and $9,000 below the price quoted to Judge Davidson a mere four years earlier by the James family. Sproul's acquisition brought ownership closer to town, and allowed local interests to seek alternative funding strategies. These emerged the following year (1946), when a Houston attorney, D.A. Simmons, offered Sproul $25,000 for 453.9 acres for the land encompassing the ruins of the old fort. Simmons had achieved an impressive career in the law, including service as an advisor to U.S. Senator Tom Connally (D-TX), to the fledgling international peacekeeping body, the United Nations, and in 1945 as the president of the prestigious American Bar Association (ABA). A magazine section of the Houston Chronicle claimed in 1956 that Simmons had first come to the Davis Mountains in 1902 with his father, assistant Texas attorney general D.E. Simmons. Supposedly the elder Simmons had "acquired" the fort "for his son . . . who was then five years old." Whatever the source of this information, the younger Simmons and his wife, the former Elizabeth Daggett, spent 30 years traveling to historic sites around the country, and it was their love of the past, said Simmons' widow in 1966, that "influenced his determination to do something about Fort Davis." [8]

The arrival of the Simmons family brought money and attention to the post that had been missing before the war from the efforts of Barry Scobee and the Mile High Club. The Houston lawyer organized the "Old Fort Davis Company," attracting as shareholders the business elite from town. Simmons told the Houston Magazine in February 1947 that he sought a "dual purpose of preserving this historical spot and for furnishing vacation homes for the ever-growing number of health and pleasure seekers who are at last learning of the scenic beauty and the health producing quality of the high, pure mountain air, both of which nature has so generously allocated to Jeff Davis." The new owner hired Dude Sproul and several other local residents to build a fence around the property, fill in the abandoned wells, erect a gate at the entrance, and convert "one of the old barracks into an information center and trading post. "The officers' quarters across the parade grounds would become "modern tourist apartments," said the Houston Magazine, and "most of the old buildings erected of adobe clay will be destroyed." Encouraging news to Simmons and the Mile High Club was "the reported plan of Dallas capital to build a fine resort near the 8,000 foot Mt. Mitre, which is only a scant dozen miles from Fort Davis." This would be proof to the outside world that the post and its environs could become "a gathering place of those who, in the summers to come will bask in the ever present sunshine and drink in the rare beauty and the pure air of 'mile high' Texas." [9]

Through his Old Fort Davis Company, Simmons was true to his word. He brought to the Mile High Club a sophisticated vision of promoting the post that included advertising in area newspapers in June 1947 about the dedication ceremonies for the completion of the 75-mile Scenic Loop Highway. The locals now had funds to print handbills that offered no less than eight reasons to stop in town, among them "The Old Fort Davis Riding Stables," managed by Ben Lotspeich; Hospital Canyon; "Indian Emily's Grave;" and "The Historic Ruins," which promised visitors the site "where Indian Emily died, and where the first Christmas tree in West Texas was set up in 1867," The source of much of this information was the Simmons-subsidized printing of Barry Scobee's book, Old Fort Davis, which incorporated all the legends and stories that the county Justice of the Peace had collected in his thirty years in town. The San Antonio Express took note of Scobee's work, and legitimized its place in the history of west Texas: "By preserving the spot's historic and romantic associations, Mr. Scobee's book should attract many Texans to visit the old fort and find their sojourn enriched." [10]

While the Old Fort Davis Company pressed the publicity angle, D.A. Simmons' work crews remodeled the first three houses along Officers' Row, and offered them for rent. This encouraged a group of five Fort Davis residents to approach Simmons in May 1948 to lease acreage in Hospital Canyon for construction of the "Fort Davis Boys Camp." They spent $10,000 to pour concrete floors upon which to install tents and a screened mess hall. They then leased the camp to a Mr. and Mrs. Tenney, managers of the nearby boys' camp at the Prude ranch, who envisioned an "exclusive prep school" at the post. This venture lasted only one summer, and by 1951 the company negotiated with Sul Ross State Teachers College and with George W. Donaldson of the Tyler school system to offer a summer institute for Texas school teachers interested in conducting their own outdoor education programs. Donaldson told the Alpine Avalanche prior to the start of the first (and only) Fort Davis teachers institute that his goal was to show postwar youth the "thousand and one things that go to make mentally rounded-out citizens in comprehending the country's resources." Speaking prophetically, Davidson warned that "many city children do not know where the milk they drink, nor the vegetables they eat, come from." The Texas educator admitted that "through no fault of their own they haven't the slightest notion of the meaning of conservation or the preservation of our national heritage of outdoor wealth and health and pleasure." Perhaps the beauty and history of Fort Davis could help "the generations now and to come . . . learn enough about these things to be instrumental in saving our country in its land and natural resources." [11]

Teachers institutes, no matter how appropriate, could not generate the revenue needed by D.A. Simmons to render Fort Davis a self-sustaining venture. On more than one occasion he confided to his wife, Elizabeth: "I don't know how we'll ever manage it, but I do not propose . . . to see that fabulous place further deteriorate." That sentiment led Simmons in 1949 to read in Texas Parade Magazine a story about the joint partnership undertaken by the state parks board, the Interior department, and the Catholic archdiocese of San Antonio to restore the Eighteenth-century "Mission San Jose" in that community. Simmons wrote to his friend, Gordon K. Shearer, executive secretary of the parks board, to explain his plans for Fort Davis and to seek advice on forging a similar agreement with the state and the NPS. He told Shearer that he had bought the post because he had learned while staying at the Indian Lodge of "a Dallas real estate man [who] was contemplating purchasing the site . . . , clearing off all the old ruins and subdividing it for mountain cabins for people in his vicinity." Simmons had heard of the work of the Mile High Club on behalf of the fort, and also "of the non-interest of anybody in Texas officialdom with authority to do anything about it." He then remarked on the power of politics to dictate creation of Texas parks: "I like Indian Lodge and the state park, but just why anybody would establish it and leave the old Fort with all of its history to disintegrate, is somewhat beyond me." [12]

Outlining his proposal to Shearer, the Houston attorney noted how he had refurbished a total of eight buildings on site, and had improved the assessed value of Fort Davis to $171,694.52. Simmons himself could not afford much more work at the post, and was being "approached by first one and then another to do something with the property." Among its suggested uses were "a super-duper dude ranch, excluding the general public, or that it be made into a super tourist motel in a transcontinental highway chain, etc." Clearly these options did not appeal to the former ABA president, who reminded Shearer: "I need not stress my point that it should be preserved for posterity." Simmons knew of the state park's board's "lack of funds," and that the legislature, "unless pressured by blocks of voters, is not likely to buy property for the interest of future generations." He then referred to Barry Scobee's Old Fort Davis, which called the post "the most active of the Indian forts in the [18]50s, 60s, and 70s." For this reason, said Simmons, "the people of this country in centuries to come will be more and more interested in this site." His records indicated that the post had "approximately" as many visitors "as are going down to the Big Bend National Park," and predicted: "Since it is the only cool summer spot in West Texas and is halfway between Carlsbad Caverns and the Big Bend Park, attendance in the future will undoubtedly grow by leaps and bounds." Simmons then closed by suggesting that in the event of his death (which would occur two years later), "I am quite sure the property would have to be sold for inheritance taxes." Given the postwar growth in travel that Simmons had outlined, he warned that someone else would be tempted to commercialize the fort; an outcome "which I would personally regret." [13]

Gordon Shearer did not offer any optimistic words to Simmons, who then hired a series of custodians to manage the property. The first couple to run Fort Davis were relatives of Mrs. Simmons, Mr. and Mrs. Walter M. Daggett of Pecos. They operated the post for one summer, and then the Simmonses contracted in 1950 with Ed Bartholomew of Houston and Leslie R. Scott of Alpine. The latter had been a radio announcer with KVLF-AM, and agreed to live year round at the fort. The Alpine Avalanche reported on January 13, 1950, that Scott would oversee a cafe, trading post, and "whatever seems needful to attract visitors to the Old Fort." Mrs. A.N. Alkire, the Fort Davis correspondent for the Avalanche, gave special mention to the post's "curio display," which she described as "the largest collection of Indian artifacts in this section of the country." She also noted that Scott would host a series of radio broadcasts on his former station, three times weekly, that highlighted the area in a "variety show" format of "music and talks." Scott, however, did not stay long at the fort, and Simmons replaced him with Louie Wiggs and Juan Razo. Ed Bartholomew also broke the lease after one year, and the Simmons family faced hiring more custodians without the prospect of additional revenue. [14]

The latest in a series of reversals of fortune for Fort Davis occurred in March 1951, when D.A. Simmons died of a heart attack at the age of 53. His wife, who would later marry John C. Jackson, recalled in 1966 how her husband's passing "spared him much of what I saw and experienced later" in managing the post. She wrote to the then-superintendent of the historic site, Franklin Smith: "You would have enjoyed knowing him, for he was a man of great depth, keen perception and vision." Without his advice and guidance, Mrs. Simmons advertised in the spring of 1952 in a series of Texas newspapers for someone to take over management of the post. The only serious respondent was Malcolm "Bish" Tweedy, a 34-year old war veteran and graduate of Princeton University whose father had been born and raised on a ranch west of San Antonio. Tweedy, who was living in San Angelo at the time, had married Sally Godfrey of Carlsbad, New Mexico, the year before, and their honeymoon had included an automobile trip to Big Bend and the town of Fort Davis. The young couple eventually wanted more regular working hours, and their sense of history and drama (they had met while working at the San Angelo Civic Theatre) led them to answer Mrs. Simmons' solicitation. [15]

The arrival of the Tweedys to Fort Davis began the final phase of the quest for a national park at the old post. Bish and Sally fell in love with the ruins, as they touched their sense of the romantic ((Bish recalled 43 years later that the grounds were "eerily beautiful"). They moved into one of the restored officers' quarters, took charge of the soda fountain and gift shop, and tried (unsuccessfully) to operate "The Bandana Room ," a restaurant where Sally cooked and Bish served guests. Their chief source of income was the gift shop, a venture that paid for itself with the steady visitation of summer ("10 to 20 people during the week days and often up to a hundred or more on weekends"). The first winter (1952-1953), however, brought few tourists and less money to cover the $300 monthly lease. The Tweedys did have more time to roam the grounds, unearthing dozens of artifacts, and to witness the continuing process of deterioration. One legend that the Tweedys encountered was the discovery of over 100 whisky bottles buried by the post sutler behind his store just before the Confederate forces in 1861 marched into the Fort Davis area. The sutler, whom Tweedy learned was "a stubborn old Yankee from New England," supposedly did not want the "'dang rebels'" to drink his whisky, and he hid the bottles so that they could not be confiscated for a Southern victory celebration. In reality, the bottles were discovered (buried end to end) on Sleeping Lion Mountain (west of the modern-day parking lot). Bish Tweedy conceded some four decades later that the NPS may never know the real story of the buried whisky bottles. [16]

This revelation led the Tweedys to close their dining room (they had served only about one dozen patrons that winter), and to convert the space into a museum. The notorious bottle collection was the "centerpiece," although visitors seemed eager to pay 25 and 50 cent admissions to view their "1858 quarter, the 10th Cavalry stencil and a lovely little brown earthenware ink bottle." The success of history as a drawing card for the Tweedys prompted them one night to discuss at a bridge game with George and Flora Merrill, longtime residents of Fort Davis, the need to preserve the site in some organized fashion. The Merrills agreed with the post caretakers that failure to solicit support from the federal and state governments rendered the next step "a community effort." Thus on February 18, 1953, the Tweedys hosted at their small museum 13 interested residents of the surrounding area who voted to become the "Davis Mountains Historical Society." They also decided to invite additional members for a second meeting on February 25, which selected as its officers George Merrill as president, R.D. McCready as vice-president, and Sally Tweedy as secretary-treasurer. Bish Tweedy agreed to become chairman of the museum committee, while Barry Scobee consented to assist him. Finally, the gathering voted to change their name to the "Fort Davis Historical Society," and to solicit funds for the "acquisition and preservation of the old Fort Davis Army Post and the preservation and marking of historical landmarks in the Davis Mountains area. "They would also attempt to "collect and display objects of historical interest in a suitable museum and to preserve in writing or in permanent form the interesting historical talks and events of this area since the days of the early settlers together with such photographs and documents as may deserve preservation." [17]

Energized with the ambition to succeed where others had failed, the Tweedys and their historical society colleagues undertook a letter-writing campaign to ascertain the merits of their proposal. A guest at the March 8 meeting, Mr. V.E. Smith, informed the group that "the national government is definitely interested in the restoration of the fort." It seemed that the NPS had inquired in February 1952 about including Fort Davis in its next round of studies, but no action had been taken. Mrs. Simmons came to the May 11 gathering in town, and expressed her interest "in working with the society to turn [sell] the property." At this point the members called upon Sally Tweedy to inquire of state officials the status of the Texas Historical Survey Commission. Allan Shivers, governor of Texas, replied that the commission would be appointed soon, and that he would support the inclusion of Fort Davis, as "several other people have written to me about this famous frontier post." [18]

One member of the society had also written to Lemuel "Lon" Garrison , superintendent of Big Bend National Park, seeking his advice on the process of incorporation into the park service. Garrison wrote to M.R. Tillotson, Region III director, informing him that the historical society had invited him to their June 8 meeting to offer guidance on application procedures. Tillotson indicated official approval of "the revival of interest in the preservation of old Fort Davis," and considered it "highly desirable for you to attend the meeting . . . and keep in touch with further activity on this line." He did warn the Big Bend superintendent: "Fort Davis has not been approved or definitely classified by the [NPS] Advisory Board . . . and that a conservative attitude towards new proposals is to be expected in general." The regional director also warned Garrison that local interests needed to know that NPS designation as a "national historic site," with management by the state of Texas (as had been done for "San Jose Mission National Historic Site" in San Antonio) meant that "the Service would not then be actually taking it over and probably would not be in a position to contribute a great deal toward the area's development." San Jose, by comparison, had received "technical advice and some assistance but very little actual cash." [19]

Traveling to Fort Davis on June 8, Lon Garrison met with 30 residents eager to hear how their neighbors to the south had brought the Park Service to far west Texas. The Big Bend superintendent gave the society a basic overview of his park, including "a review of tourist travel economics." In the question-and-answer session that followed, the most prominent query was "that the National Park Service might take over the area for restoration after purchase and administration as a National Monument." As politely as he could, Garrison outlined the paper trail from the NPS regional office to the service's s advisory board. He also "added that as a practical matter the problem of securing funds for the extensive work necessary just seemed almost impossible." In his report to Tillotson, the NPS official said that "the group [historical society] does not seem to be well unified, which is regrettable, for old Fort Davis is a charming place and deserves better treatment than it is receiving now." Garrison remarked on the efforts of D.A. Simmons to restore the property; a rendering that he considered "far from accurate." "Most of the buildings are about gone," the superintendent reported, "and another year will just about complete the ruin." Further complicating matters was Bish Tweedy's statement to Garrison that "Mrs. Simmons is now asking $200,000 for the 480 acres which is quite unrealistic in [the superintendent's] opinion." [20]

|

|

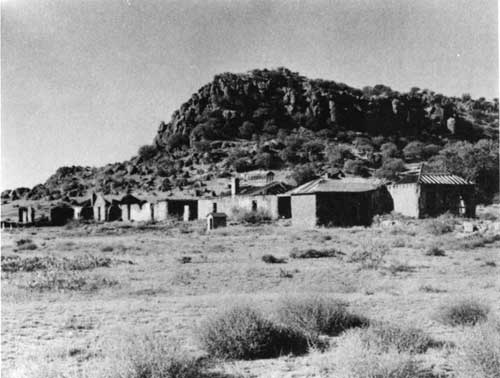

Figure 8. Hospital Steward's Quarters in ruins

(1950s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 9.Ruins of Officers' Row (1953).

Part of Littleton Report on Southwestern Forts. Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 10. Fort Davis Historical Society

Parade at Centennial of Fort Davis (July 1954). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

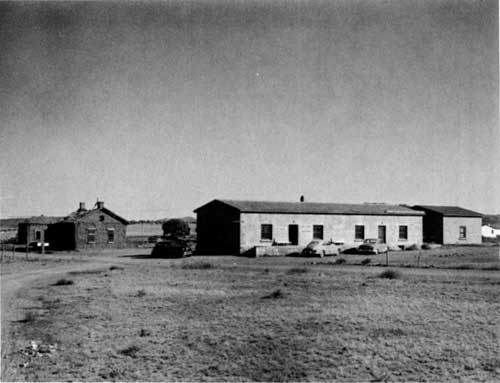

Figure 11. HB 1-2-3 (Officers' Quarters)

used as guest cottages in late 1940s. Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

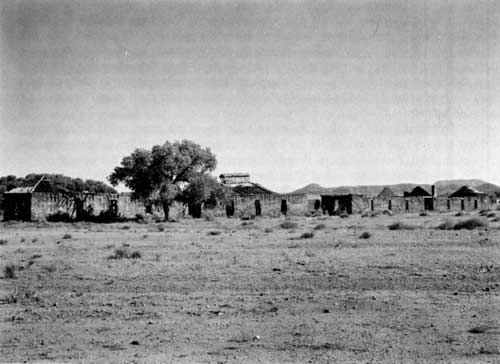

Figure 12. Ruins of Officers Row, Old

Sutler's Store in background (1950s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 13. Fort Davis Historical Society

Museum in Operation (Sept. 1953). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 14. Officers' Row (early 1950s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 15. Ruins of Chapel with HB-15

(Two-Story Officers' Quarters) on left (Sept. 1953). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 16. Ruins of Officers' Row (early

1950s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

Despite his misgivings about the local effort on behalf of Fort Davis, Garrison sought resolution as best he could. He learned from society members of the creation of the Texas Historical Commission, and promised to seek more information about it. He also believed that the society "does not appear to be a group that will have any money to spend, and will be limited in its functions to advisory assistance only." The superintendent then reported to the Santa Fe office that "1954 is the Centennial Year for Fort Davis and they are hoping to use this as a publicity feature to secure interest in their problem." Garrison warned Tillotson: "The first job remains for them to pull together better, and this is a field where I do not believe that we can provide leadership." He then closed with a personal note that revealed why the post attracted so much attention, despite opposition or indifference to its park status: "My own grandfather who went to the California goldrush in 1849 over the Old Overland Trail, had undoubtedly been at Fort Davis both coming and going." Garrison "had not anticipated this personal tie-in with the local history," and as a result "offered to consult with them at any time they felt it would be helpful." [21]

The society was not long in taking Garrison at his word, with Sally Tweedy writing him on June 15 asking for his help in "bringing Old Fort Davis to the attention of the National Parks Advisory Board." Garrison referred to NPS manuals on the matter, and informed the regional office (as had Aubrey Neasham 14 years earlier) that "this fort might well come within classification XI of the major historical themes, Westward Expansion and the Extension of the National Boundaries, 1830-1890." He urged consideration because of the deteriorating condition of the property, but cautioned that "the matter of land status and maintenance and operational procedures should be gone into before anything further is done." Tillotson's reply indicated the ironic political clout of such an isolated place as Fort Davis: "A general survey of the old U.S. military posts of the frontier in the Southwest was requested by the Washington Office some time ago, arising specifically from a recommendation on Fort Davis." The study was "to be completed this year, if at all possible, for the consideration of the Advisory Board at their November [1953] meeting." The regional director believed that "Fort Union, New Mexico, Fort Bowie, Arizona, and Fort Davis are sure to be at the top of the list." Until then, all Tillotson could advise was for Garrison "to keep in touch generally with the Fort Davis Historical Society." Also indicative of the political sensitivity of the report, the director told the Big Bend superintendent: "We leave this entirely to you, and I feel that you have handled it excellently to date. Your memorandum of June 11 is a particularly clear and helpful report on the situation." [22]

Because it had studied Fort Davis several times in the past, the regional office of the Park Service realized how complex the political networks in Texas could be. This became evident in August 1953, when U.S. Senate Minority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson (D-TX) received a letter from Pecos optometrist Glenn E. Stone. Dr. Stone and his family had visited Big Bend for the first time after 35 years of residence in west Texas , and they wanted to inform their state's powerful senator of their dislike of the experience. "I have never seen more desolate, barren God forsaken country," said Stone, "particularly to be a national park," and he wondered how the Congress could "justify a cent of federal or state money being spent on it." The Pecos physician then informed Johnson: "What makes it difficult to understand is why the National Park Service and federal government would pass up an area of outstanding natural beauty such as is found around Ft. Davis." Stone considered the site "a point of high historical interest with lots of possibilities of development and restoration for that uninteresting wasteland." Stone marveled at the large number of people picnicking in the Davis Mountains on summer weekends, which made it "hard to find a spot that is not already taken," and hoped that Johnson could provide an answer to his question about the history of the park service in far west Texas. [23]

Known for his constituent service as well as his power in the halls of Congress, the top-ranked Democrat in the Senate submitted a terse inquiry to the NPS: "I will appreciate your giving serious consideration to this problem [the Stone letter] , based on its merits. Please let me have as prompt a reply as possible." Hillory Tolson, formerly director of the Santa Fe regional office and then-acting director of the NPS, responded to Johnson by apologizing for Stone's "uncomplimentary opinion of Big Bend." Tolson politely informed the Texas senator: "Many others have been impressed by the spectacular canyons, the geologic interest and the plant and animal life of the Park - features which were judged to be so outstanding as to merit inclusion in the National Park System." The acting director went on to describe in glowing terms the flora and fauna of the Rio Grande and Chisos Mountains, and gently reminded Johnson: "You are, of course, familiar with the great interest in the State of Texas and elsewhere in the preparations being made for the formal dedication of the Park in 1954;" an event to be attended by no less a personage than President Dwight D. Eisenhower, himself a Texas native. [24]

Because of its ongoing study of western forts, the park service decided to include some of its findings in Tolson's reply to Senator Johnson. He identified Fort Laramie National Monument on the North Platte River in eastern Wyoming as the service's choice "to interpret the role of the United States Army in aiding the opening and settlement of the American West." The letter referred to the advisory board study of southwestern posts, most notably Forts Union, Bowie, and Davis. He then mentioned a concept that President Eisenhower, a fiscal conservative, preferred for the Interior department's many projects in natural resource development; "partnership," or the collaboration of state and federal agencies to reduce costs for both parties. "Many western forts and military posts, of course," said Tolson, "images/figured prominently in our early Western history, but the Service must count upon the States and local patriotic organizations to preserve them." The Park Service to date managed 118 "historical areas," spread throughout the nation "to commemorate, so far as possible, the most significant phases of American history, within the limits of funds available for historical conservation." Tolson closed by reminding Johnson: "It is our hope that the States will be able to supplement our work by preserving other places deserving of historical conservation measures," and he said of Stone's inquiry: "We appreciate knowing of Dr. Stone's views and hope that this information will be useful to him." [25]

Lyndon Johnson's interest in the Fort Davis case put regional NPS officials on notice to monitor the work of the advisory board. In late September 1953, Lon Garrison informed his Santa Fe superiors that the Texas Garden Clubs had met in Alpine, with their 128 members agreeing to promote the necessity of preserving the grounds and buildings. In addition, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram covered the appointments of Governor Shivers to the state historical survey committee. Garrison had good news to report about the Simmons' selling price, as Mrs. Simmons supposedly "has now placed a more reasonable valuation on the land and probably the Fort Davis Historical Society will secure a firm option within a short time." Aiding the local interests was Glenn Burgess, president of the Alpine-based West Texas Historical and Scientific Society. Garrison then requested that George Grant, the famed park service photographer, stop at Fort Davis upon his departure from Big Bend, "because of the current interest in this project and the meeting of the Historical Sites Advisory Committee this fall." Grant in turn advised John O. Littleton, Region III historian, to call on Mrs. Simmons while in Fort Davis for his "brief study of the frontier military posts of the Southwest" that he was crafting for the upcoming board meeting. Littleton did not want "to give the impression that my visit implies" park service commitment. Thus he asked Superintendent Garrison to offer some advice on the sentiments of the local sponsors prior to his arrival in the Davis Mountains. [26]

Garrison's correspondence about the historical survey commission was prompted in part by the assiduous cultivation of that board by the Fort Davis proponents. An example of their exertions came in a letter from Barry Scobee and other members of the Old Fort Davis Company. Writing in November to Judge J.R. Wheat, chairman of the selection committee for state historic sites, Scobee et al. , offered to travel to Austin to speak to Wheat's organization on behalf of a post that they deemed a "famous and remarkable old landmark that is so interwoven with Federal, Confederate, and Indian history." The Scobee party then informed Wheat that they knew "that in the same month President Eisenhower will dedicate the Big Bend National Park." Scobee hoped that Wheat's board could "induce the President to appear at the old fort celebration and thereby focus public landmarks." Gene Hendryx of Alpine, by now employed at KVLF radio, remembered that the locals believed that they could convince the former Supreme Allied Commander of the merits of Fort Davis because of his military background. Thus the Old Fort Davis Company was disappointed yet again when the White House could not accommodate their request. [27]

Inured by this time to the vagaries of park promotion, the historical society proceeded throughout 1954 with plans to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the establishment of Fort Davis. The event, which was held on the weekend of October 9-10, tapped the historic resources of the Davis Mountains like no other celebration that old-timers could remember. John G. Prude, of the prominent local ranching family, was president that year of the historical society, and he also served as grand marshal of the parade. Jacobsen and Nored mentioned that this event "represented nearly every family in the area, some of which included four generations." By having the major economic interests heavily involved, along with the public schools, the society for the first time demonstrated the potential for Fort Davis to serve as a focal point for community life. This expansive mood touched the Hispanic neighborhood of town, as they hosted a rodeo and barbecue. In keeping with another old tradition, however, Anglo and Hispanic revelers retreated to separate dances in the evenings; the latter at the Anderson elementary school, the former at the high school. And in keeping with the legendary character of the celebration, Herbert Smith, superintendent of the Fort Davis school system, directed the "Indian Emily Pageant," which Pansy Evans Espy, related to two prominent families in the area, remembered decades later as very moving, if not historically accurate. [28]

The centennial celebration continued for several years after 1954, with its successor first the "Old Fort Days," then a more modest picnic at the cottonwood grove east of the post. The historical society, however, made do without the services either of the park service or of Sally and Bish Tweedy. In February of that year, Lon Garrison received word from the NPS advisory board that "while Old Fort Davis was mentioned, no definite favorable action was taken on designation as a desirable area for inclusion." The Big Bend superintendent "assumed that this simply means that the Advisory Board is awaiting a further study and report, although generally favorable to the idea of preserving evidences of the western expansion." Garrison then asked Regional Director Tillotson about the most sympathetic means of explaining this to the local historical society, as "you are much closer to the overall picture including Fort Bowie and Fort Union than I am." Tillotson was not optimistic, telling Garrison: "The net effect of the Advisory Board reaction concerning Fort Davis . . . is that although it might be desirable to have Fort Davis or Fort Bowie or both, as well as Fort Union, it is not practical at the present time to make any attempt at acquisition or even recommendation." Again the rationale was the scarcity of funds in a conservative political age. Garrison's reply to the Fort Davis sponsors was thus the same as in previous studies: "The National Park Service . . . could re-consider Fort Davis only if and when appropriations become adequate for the minimum essential current needs of existing areas." [29]

No amount of local enthusiasm could substitute for federal spending on Fort Davis or its restoration, and this latest rejection at the hands of the advisory board traumatized the Simmons family and the Tweedys alike. Both faced bleak financial futures with their fortunes linked to private management of the fort; the former in need of monies to reduce the debt on the property, while the latter faced a growing family (two daughters born while the Tweedys lived on the post grounds) with no increase in income to compensate. In the fall of 1953, Bish Tweedy explored the possibility of teaching in the local public schools, but discovered that he needed a state of Texas teaching credential. In order to do so, he moved his family the 26 miles to Alpine to attend Sul Ross Teachers College. The Tweedys, who had done so much to revitalize Barry Scobee's dream of a park at Fort Davis, thought that they could negotiate with Mrs. Simmons to permit them to leave the property vacant during the week (when the Tweedys hosted few visitors), and return on weekends to meet their obligations to the public.

When Mrs. Simmons heard the Tweedys' request, she denied it categorically, saying that she could not have the property left unattended. This exacerbated the strain under which both families operated. At one point Mrs. Simmons demanded that the Tweedys vacate the fort, and Bish and Sally found themselves without support. Their fate turned out better than expected, as Bish gained employment through the Princeton network at a private boys' school outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where for 24 years he taught history. The Tweedys did not discard their love of local history and old military posts, however, as they took over management of Fort Ligonier near their new home, and restored it to the point that Fort Ligonier Days became the largest historical celebration in western Pennsylvania. [30]

For the remainder of the 1950s, the Fort Davis Historical Society labored to maintain some semblance of continuity in their quest to purchase the post from Mrs. Simmons. Custodians came and went with the same frequency as before, none of whom could make Fort Davis any more of a paying proposition than Sally and Bish Tweedy. The society tried to make the "Old Fort Days" more of a carnival than an historical celebration, as in 1956 they brought to town Oklahoma Indian dancers, Navajo sand painters, museum exhibits from the Big Bend Art Club, soldiers from the Texas National Guard, and the Odessa Junior College drill team, "Las Senoritas de las Rosas." Once again they produced the "Indian Emily" episode to the delight of visitors, and served buffalo meat at the barbecue; certainly an historical novelty in the heart of Texas cattle country. Events such as these cost nearly as much as the celebration received in gate receipts, however, and in that year the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) came to Fort Davis to claim that the historical society (which apparently had not incorporated as a non-profit entity) owed back taxes on their income. This led to an embarrassing sequence of letters between Mrs. Simmons, the society, and the IRS that detailed just how far the locals needed to go to purchase the fort. Her asking price was $115,000, and the earned income was not sufficient to send Mrs. Simmons even $250 per quarter in lease payments, let alone make a down payment on the old frontier fort. [31]

In May 1957, U.S. Representative J.T. Rutherford (Democrat from Odessa) asked Barry Scobee to rekindle efforts to preserve the post with federal money. Elmo Richardson wrote that "the greatest obstacle to preservation of the natural environment" in the post-World War II years "was the American tradition of progress." For Americans touched by the double trauma of depression and global conflict, "renewed development of resources was elevated into one of the primary tasks of the federal government." In the late 1940s, a conservative Republican congress, eager to dismantle the excesses of the prewar New Deal, entertained a proposal from "several western congressmen . . . that units of the national park system be opened to mineral exploration and lumbering." Again in 1952, critics of the Interior department wanted that agency's operating principle to be "one of disposition, not acquisition," which Richardson described as " 'returning' the public domain and its resources to the states." The ascendancy of the World War II commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower, to the presidency from 1953-1961 brought to western resource development what Richardson called a "shared . . . belief in the commonality of individual effort and success." [32]

All was not lost for the patrons of American history and culture, however, as the competing force of preservation touched the West by the mid-1950s, culminating in the battle between two Interior department agencies, the NPS and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), over the latter's plans to construct a large multipurpose water project on the Colorado River within the boundaries of Dinosaur National Monument, on the border of western Colorado and eastern Utah. Massive outpourings of support for the park service (the famed Utah native and Harper's Magazine columnist, Bernard DeVoto, wrote a disparaging piece that year entitled, "Let's Close the National Parks") led Eisenhower officials to reject the USBR's scheme, and to push for NPS director Conrad Wirth's idea of "MISSION 66," described by Richardson as "a coordinated plan . . . whereby expanded facilities in parks and recreation areas would make it possible for the system to accommodate 80 million visitors by 1966 [coincidentally the golden anniversary of the park service itself, and the dedication of Fort Davis]." Wirth realized that political realities dictated every step that his agency took, and in Richardson's words, ensured the future of parks like Fort Davis because he "perceived that he could secure funds by making Republican legislators and administrators aware of the terrible conditions [in the system] and then turn the rescue actions to their political credit." [33]

Of equal benefit to the promoters of Fort Davis was the national mood by the late 1950s favoring the historical interpretation of the West that Lady Bird Johnson dramatized at the 1966 dedication ceremonies. Michael Kammen noted that MISSION 66 "meant striking expansion in historical programs and in types of historical sites." As the pressures of the baby boom, the Cold War, and the nascent civil rights movement entered the consciousness of Americans, Kammen detected a desire for nostalgia, which he defined as "most likely to increase or become prominent in times of transition, in periods of cultural anxiety, or when a society feels a strong sense of discontinuity with its past." By 1960 the nation, in Kammen's words, would seek anew "patriotism, hero worship, and their historical underpinnings." This phenomenon came to be known in later years as the "heritage emphasis," but Kammen believed that "heritage that heightens human interest may lead people to history for purposes of informed citizenship." Whatever the purposes of the Fort Davis boosters, the nation was more ready for remembrance of things past in the late 1950s than ever before, and the journey taken five decades earlier by Carl Raht and Barry Scobee to divine the story of the Davis Mountains would finally reach its end. [34]

Promoters of the old military post moved cautiously in the months after announcement of the MISSION 66 initiative, mindful of the rejections that their entreaties had met since the early 1920s. One reason was the lack of enthusiasm within the Southwest Regional Office of the park service (SWR), which had, in the words of its historian in the late 1950s, Robert M. Utley, "said all the right things about history," but which was "heavily archeological," dating to the days of Frank Pinckley and his formation of the Southwestern National Monuments (SWNM) organization in the 1920s.

Utley, who would become chief historian in the Washington office of the park service, and later director of its "Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation," pointed out in an interview in 1994 that SWR "moved slowly" on completing its historical research mandated by the 1935 Historic Site Survey. This was due in part to the NPS decision to suspend new surveys after World War II, given the conservative fiscal mood of Congress. All this would change, however, with MISSION 66, and in 1957 the park service reinstituted the Historical Survey project. [35]

Word of this change of heart on the part of the NPS energized Barry Scobee and his contemporaries in the town of Fort Davis, especially when they learned from Representative Rutherford that he wanted to build local momentum for creation of a park. A World War II soldier, the Odessa native had returned to Alpine with his veterans' benefits to attend Sul Ross Teachers College. There he had been a classmate of Gene Hendryx, and the two of them often had driven the 30 miles north to Fort Davis to roam the grounds of the post and climb in its ruins. Upon his election to Congress in 1954, the moderate Democrat pondered on ways to fulfill Barry Scobee's dream, and in May 1957 wrote to Scobee to test his idea for generating public support. Based upon notes Rutherford had accumulated for the past two years, he thought that Scobee should set up an "Old Fort Davis Association," with membership and annual dues to sustain the promotional efforts. Linkage of the military history of Fort Davis to the campaign would work well in a conservative climate, thought Rutherford, as "members would enter with the rank of 'Trooper,' 'Sergeant,' and the like." Scobee should then embrace all the trappings of organizational structure, planning for some sort of "annual convention" which "alone would bring a sizeable group of people to the community." Finally, the association could not go wrong with the historical connection of the fort to the Indian wars, as Rutherford believed that "people are enchanted by the spirit and traditions of the Old West, and this would be in our favor." [36]

Rutherford's interest motivated the historical society to redouble its efforts to raise funds for the purchase of the fort property from Mrs. John Jackson (remarried after the death of D.A. Simmons). Further exciting local sponsors was the arrival in Fort Davis on October 15, 1957 of U.S. Senator Ralph W. Yarborough, who toured the museum maintained by the historical society, and inquired about the "practicability of the public obtaining title to the Fort and of having it declared a National Historic Site." The junior Democratic senator from Texas had first come to the fort in February 1929, when he was a young lawyer in El Paso. Taking an automobile trip with his friend, Tom Newman, Yarborough marveled at the sense of history that the site conveyed; a sense that mirrored his own love of the westward movement. Yarborough returned to Fort Davis on several occasions (even after leaving El Paso in 1931), and in the late 1930s he worked again in the Trans-Pecos area as an assistant state attorney general on the legislation to create Big Bend National Park. Unfortunately for Yarborough and the Fort Davis supporters, he learned soon after his October 1957 visit that the Jacksons' asking price ($115,000) was "so high that it had not only delayed the creation of a National project there, but had almost destroyed the feasibility of it." [37]

Determined as never before to overcome the financial obstacles facing Fort Davis, Barry Scobee and the historical society met in February 1958 to discuss the lease held by Mrs. Jackson. The $1,000 lease payment that they made to the Jackson family "was considered by most of the members as too much," Scobee told his friend Frank Temple of the Texas Technological College library, and he moved that the society "give up operation of the Trading Post, as it was the money eater . . . but to continue the museum if possible." In the interim, Mrs. Jackson had visited Fort Davis and agreed to reduce her lease charges to $300 per year over a three-year period. Then in October 1958, the historical society convinced Mrs. Jackson to give them a purchase-option on the post (a total of 450 acres), prompting society president G. Martin Merrill to write NPS director Conrad Wirth informing the park service of this change of status. Wirth's office gave the society hopes that Washington had also changed its attitude about Fort Davis, advising Merrill that the renewed Historical Sites Survey program that year included the theme of "Western Expansion." Because "military and Indian affairs" comprised part of the mandate of the 1958-1959 survey, Fort Davis would be part of any list of potential parks that the NPS sent to Congress. The director's office also suggested that the historical society be aware of the distinction between a national monument and a national historic site. The park service could not guarantee under which category Fort Davis might fit, but Representative Rutherford assuaged the doubts of the local sponsors in May 1959 when he described the survey as "a long-range program now in its early stages." "You may count on my cooperation in every way possible," he told Frank Edwards, manager of the fort property in a letter reprinted in the Alpine Avalanche, and he cast the situation in as broad a context as possible with his closing remark: "I realize the establishment of Old Fort Davis as a national shrine would be a great asset for West Texas and l have a high personal interest in it." [38]

The critical person for Fort Davis now was no longer someone from the surrounding area, nor even Mrs. Jackson, but the Secretary of the Interior, Fred A. Seaton. A former owner of several small-town newspapers in his native state of Nebraska, Seaton had replaced in 1956 the embattled Secretary of the Interior, Douglas McKay, chastised for his role in the Dinosaur National Monument fiasco, and ridiculed in the media for his previous connection to the business world as a Chevrolet automotive dealer in the state of Oregon. More diplomatic and experienced in politics than his naive predecessor (known as "Giveaway McKay" for his leasing of public lands to private interests), Seaton believed in President Eisenhower's "partnership" principle for resource management. This included, in the words of Elmo Richardson, a "deeply held conviction that the government should do only those things which the states and the people could not do for themselves." Compounding Seaton's problems was the announcement in 1958 by the Eisenhower administration that it wished to reduce funding for MISSION 66 by half; a situation that the Democratic U.S. Senate reversed, and instead increased by some 100 percent. Seeking compromise between what Richardson called the "intentions and reality" of national resource policy, Seaton eventually in 1960 called for "a 'Mission 66' whereby the Bureau of Land Management [BLM] could develop recreation sites, and a 'Mission 76' to provide federal assistance to the states for their own park and recreation programs." [39]

The reasoned logic of Elmo Richardson, reflecting years later on the caution of the Eisenhower administration, did not suffuse the correspondence of SWR historian Robert Utley, whose task it was to survey the importance of Fort Davis for inclusion in Conrad Wirth's report to Congress. Disheartened not only by the dilatory tactics of Seaton, but by what he perceived to be the limited understanding of local interests in the machinations of Washington politics, Utley returned from his visit to Fort Davis in the fall of 1959 determined to change attitudes from the local to the national level about the abandoned post. In an interview years later with this author, Utley described the historical society's operation of Fort Davis as "real sleazy," especially the bohemian lifestyle of the artist-caretaker, Rodolfo Guzzardi, who seemed incapable of halting the vandalism that had increased over the years. "The locals didn't know how to promote Fort Davis," said Utley, and as for Barry Scobee: "He was full of the legends," and was "part of a network of west Texas historians [who told] half-real/half-mythic stories." The most odious of these tales that Utley and the NPS would confront was Scobee's "Indian Emily" story, reinforced by the prominence of the Texas Centennial Commission marker on the post grounds. Scobee, in Utley's words, "knew deep down that [the legend] was wrong," but their disagreement over its veracity did not keep the justice of the peace from assisting "the kid," as Scobee called the park service historian, in the collecting of documents and interviews. [40]

Caught between parochial interests and national politics, Utley then took the boldest step that a public official can make. He orchestrated a secret campaign of support for the creation of a park at Fort Davis, fully aware of the consequences to his career as well as to the future of the site. Like many veterans of military service in the postwar era, Utley believed deeply in the importance of military history to the national story. He also shared the public's fascination with the West, having begun his career with the NPS at the age of 17 as a seasonal ranger at Custer Battlefield National Monument (renamed in 1991 as the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument).

Utley chafed at the constraints of bureaucracy, and knew that popular sentiment would override any intransigence on the part of his superiors. Evidence of this was the fact that 17 of the 26 highest-rated television shows that year were westerns, and the heroics of John Wayne as a soldier-scout, or cowboy, had regaled moviegoers since the premiere in 1939 of the film Stagecoach.

The regional historian's ally in this strategy of subterfuge was John Porter Bloom, assistant professor of history at Texas Western College in nearby El Paso. Bloom, the son of Lansing Bloom, longtime editor of the New Mexico Historical Review and himself a veteran of military service, had known Utley through their associations in the Westerners International (to which Ralph Yarborough belonged as well), and their membership in the Historical Society of New Mexico. In October 1959, the NPS advisory board had included Fort Davis "as a site possessing exceptional value for the purpose of commemorating and illustrating the history of the United States. "Yet Utley had learned soon thereafter that Secretary Seaton was "adopting what appear to be a number of stalling devices to avoid releasing the recommendations of the Advisory Board and thus taking a positive stand on several issues." "Lord knows," said the NPS historian, "when it will be publicly announced that the Park Service wants Fort Davis." Aggravating matters for Utley was the fact that the local historical society "could almost certainly get one of the Texas congressmen or senators to introduce a bill in the next session of Congress authorizing creation of the Fort Davis National Historic Site." Utley predicted that "the man who would write the [NPS] report is a devoted champion of Fort Davis [a reference to himself]," and Seaton would be forced to "sign the report rather than, in effect, repudiate his own Advisory Board." He could not "start the ball rolling without getting myself into trouble," and SWR could not "let the Fort Davis supporters know how to break the log jam." Thus Utley asked Bloom "discreetly and without divulging your source [to] make the above facts known;" a service which "might well advance the cause of historic preservation in Texas a long, long way - and it has a long way to go." [41]

John Porter Bloom was as good as his word, engaging in an extensive campaign of correspondence throughout west Texas, and in Washington, DC, on behalf of Utley's request. Barry Scobee offered Bloom some background on previous attempts to create a national park at the site, remembering in January 1960 how Big Bend's appropriation had denied Fort Davis access to state funds for purchase of the post. Then World War II terminated all non-essential activities in Congress. "I have seen a dozen moves to buy the fort," said Scobee, "and we have always come out minus." Bloom also encouraged his own El Paso Historical Society to pass a memorandum in favor of Fort Davis. He went so far as to approach Senator Johnson, who in the winter of 1960 was the Senate majority leader and was contemplating his own candidacy for the presidency of the United States. Johnson asked Conrad Wirth to "give me your views and opinions, however tentative, on this . . . most interesting proposal." Representative Rutherford, now on the House subcommittee that oversaw the national parks, agreed to draft legislation creating Fort Davis National Historic Site, and the NPS director could inform Senator Johnson on March 4: "We are undertaking further studies relative to Fort Davis to determine whether this Department should support the proposal to establish it as a national historic site." [42]

On February 10, 1960, Representative Rutherford introduced in the House his bill (HR 10352) to designate Fort Davis as a national historic site. In his letter to Representative Wayne N. Aspinall (D-CO), chairman of the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Rutherford asked for help in "scheduling hearings on this bill as quickly as possible and convenient." He then detailed the significant historical features of the post, calling it "an important link between the East and the West of the United States." Fort Davis was also near Texas's "only National Park - Big Bend," and inclusion in the NPS system would "give [Fort Davis] added attraction in a historic area." Rutherford then drew attention to one of his favorite stories about the post: Indian Emily. Unaware of the thoughts of Robert Utley on this issue, Rutherford repeated to Aspinall the romantic story told time and again by his friend Barry Scobee: "Many visitors come to this grave and to review the Old Fort's ruins, although no official designation has ever been given to the site by any governmental level." [43]

Within two weeks, Senator Yarborough had followed Rutherford's lead in submitting Senate Bill (S.) 3078 to create the park at Fort Davis. In both cases the lawmakers instructed their colleagues to "set aside [Fort Davis] as an public national memorial to commemorate the historic role played by such fort in the opening of the West. " Rutherford and Yarborough did depart from established congressional guidelines in requiring the Secretary of the Interior to "acquire, on behalf of the United States, by gift, purchase, condemnation, or otherwise, all right, title, and interest in and to such lands. " Heretofore Congress had wanted all new parklands donated by private or non-federal entities. But early indications were that none of Rutherford's and Yarborough's peers would criticize this effort, and on March 15, 1960, Senator Yarborough had included in the Congressional Record an article from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram praising the work of Barry Scobee on Fort Davis. The park service also swung into action, designating Robert Utley in March to be the author of the historical report on Fort Davis. Utley, said Conrad Wirth, "will be familiar with this aspect of the task since he has performed similar work in connection with the studies of Fort Bowie and Apache Pass [in southeastern Arizona] and the report on Promontory Point [near Ogden, Utah] that is currently in progress." [44]

This last remark about Robert Utley's workload indicated the volume of research outstanding on potential park sites; a situation that did not square with Secretary Seaton's cautious strategies about "partnerships" and local initiative. To that end, E.T. Scoyen, acting NPS director, informed the Office of the Solicitor that the Park Service, while supportive of Fort Davis's inclusion in the system, should not move as quickly in providing material to Congress. "It is the best remaining example in the Southwest of the typical post Civil War frontier fort," said Scoyen, but "we have not yet carried out studies needed to indicate what would be desirable boundaries of the proposed historic site in order to provide for protection and preservation of the site and its structures." Hence the Park Service hoped for a modest delay, and expected that Utley's study "will be completed in time to permit a report to the Congress . . . before the end of this session." Rutherford, however, noticed a problem in April when "these kind of bills [began] having rough sledding on the Floor [of the House] this year." The west Texas congressman wrote to Barry Scobee on April 19: "Rather than take the bill up now in the mad scramble toward an early adjournment, and with tempers short, I had about decided to wait until the beginning of next session to push the Fort Davis bill on the theory that a 'good humored' House would be more receptive then." [45]

Robert Utley proceeded to Fort Davis soon after announcement of the delay in the site's progress through Aspinall's committee. Working hastily in the election year of 1960, Utley completed a draft of the Fort Davis report by May, and submitted it through channels in the Park Service. The regional historian made clear in the first section his intent for Fort Davis: "Its mission will be to recall vividly through the nostalgic atmosphere of a remarkably well preserved frontier army post the loneliness and frustration, the laughter and song, sorrow and tragedy, and the nomadic feeling of infantry and cavalry garrison life in the late 19th century." Utley marveled at the relatively slow process of deterioration at the site, which an aerial photograph in 1924 "revealed that all or portions of the entire fort as constructed were still standing although evidences of destruction were noticeable." He found that spring "seven quarried stone buildings [along officers' row] whose walls are intact and three of these have been maintained, reroofed, and are equipped for occupancy." His architectural summary concluded: "The most striking difference between this site and others of the same general period and influence is the large extent of ruins remaining. [46]

Turning to the work remaining before the site could open for business, Utley suggested that "the visitor to Fort Davis should respond to the mountain setting and become imbued with an interest in the extensive century old remains." He called for "stabilization of the remaining adobe ruins, restorations of at least some of the stone officers' quarters and other important buildings, replanting with trees and sod and installation of an authentic flagpole on the parade ground." Utley suggested that the visitor should also have access to a "small visitor center to accommodate exhibits associated with the fort and the accomplishments of the personnel garrisoned there," with "the main interpretive devices [being] in-place exhibits at appropriate locales accessible from hard-surfaced trails." Because the site and community were "practically contiguous," Utley saw no need for concession services. He did warn that "the Service will encounter adverse development across the highway from the fort," but this he believed would be "no worse than during the years when the fort was active." One could not easily stop "motels, service stations, lounges, curio shops, etc.," but these "will only tend to increase the atmosphere of non-commercialism within the proposed Service area." [47]

The Fort Davis draft report circulated among Utley's contemporaries in other offices of the Park Service, including that of Kenneth Saunders, SWR architect. He joined a party of regional officials on a tour of Fort Davis in mid-June 1960, reporting on the cost of restoration work at the site. Saunders counted a total of 49 buildings and structures, comprising an "original architectural design" that he considered "not outstanding." In addition, "throughout the United States there are now many fine examples of this period of architecture that are still in excellent condition." He judged "the majority of the remaining buildings or structures at Fort Davis [to be] in poor condition far past the time for reconstruction or rehabilitation and are unsafe to walk around." Saunders called on the Park Service "to remove all old lumber (roof structures, stud walls, etc.) and exterior walls of adobe buildings." In their place he wanted "complete restoration of eight typical examples of the old buildings." His plan would cost some $273,500, and would provide the visitor with "a fine idea of old Fort Davis as originally built." [48]

The Saunders report drew criticism immediately from Utley and others in the regional office, as it threatened further delay of final approval of Fort Davis. Erik Reed, SWR chief of interpretation, told the regional chief of operations that "if Fort Davis is added to the National Park System, it will be because of the historical significance of the post (and the buildings) rather than of the aesthetic values of the structures." Saunders' suggestion to dismantle buildings and tear down walls also irritated Reed, who preferred to "strengthen what remains by capping and/or re-roofing. " The Saunders report thus triggered rapid responses from other study team members, and Roland Richert, the acting supervisory archeologist who had accompanied Saunders to Fort Davis, sided with Utley and Reed: "The review, advice, and recommendations of the Interpretive Branch with respect to any or all structures are considered essential for achieving maximum objectivity and accuracy in final appraisals and planning for the area." [49]

As the Saunders report drew fire within the regional office, the final version of Utley's "Area Investigation Report" for Fort Davis became available. In it the historian was much more thorough than he had been in the four-page synopsis submitted in haste in May. Utley remembered that in 1953 the region had assigned John Littleton to prepare a report entitled, "Frontier Military Posts of the Southwest. " Littleton believed that Forts Davis, Union and Bowie offered the best evidence of the Indian wars fortifications. Because of its proximity to the SWR headquarters in Santa Fe, as well as that city's tourist trade, only Fort Union received favorable treatment from the park service as a result of the Littleton report. Utley conceded that Forts Union and Laramie already interpreted the Indian wars for the general public, making the costs of land purchase and building restoration at Fort Davis a challenge. Yet in its favor was the presence nearby of two major national parks: Carlsbad Caverns to the north, and Big Bend to the southeast. Utley expected Fort Davis to draw better than Fort Union (14,000 in 1959), but less than Fort Laramie (41,000 that year). [50]

Most critical to the success of Utley's plans was purchase of the 454-acre tract from Mrs. John Jackson and her family. The Fort Davis Historical Society was hard-pressed to generate much more than the $1,500 per year lease payment for the property, plus operating expenses. "None of the present uses would be consistent with Service policy," Utley concluded, as these encompassed not only the museum, rental quarters, and "curio shop," but also riding stables (with twelve horses grazing on the grounds), and a Church of Christ summer camp in Hospital Canyon. Utley suggested that the NPS offer to purchase about 440 acres from Mrs. Jackson, as a tract of 14.6 acres held "no historical or developmental value." "The only additional lands" that he could detect "would be the head of Hospital Canyon to assure scenic control and prevent a possible access problem to the 3 to 5 acres within the canyon owned by local landowner, H.E. (Dude) Sproul." [51]

It was when Utley examined the Jeff Davis County tax records that he learned of the variance between what Mrs. Jackson paid in taxes for the property, and what she wanted the federal treasury to reimburse her for the improvements on the land. "For the Assessor's office the assessed value is approximately 1/4 of true value," said the historian, which rendered "an approximate true value . . . in the neighborhood of $50,000." Utley could not estimate the cost of restoration, although the alterations made by private interests "do not appear to have wrought any irreparable damage to the integrity of the area." As for the loss of tax revenues on the property for Jeff Davis County, because Mrs. Jackson already paid so little in taxes, Utley believed that the modest decrease of county ($96.00), state ($50.40), and local school revenues ($240.70) "would almost certainly be compensated by an increase in business activity and by an resultant nominal increase in land values within the town of Fort Davis. [52]

Upon receipt of Utley's report, the SWR director compiled a memorandum for the NPS director's use with Congress. Two problems surfaced that the regional office could not dismiss: the high cost of restoration, and the lack of unified local support for the park. "The question of restoration-rehabilitation-stabilization is certainly wide open for further consideration and discussion," said regional director Thomas J. Allen. "Should Fort Davis National Historic Site be authorized," the Park Service faced "costs for the first five years of operation . . . at $1,170,200, with an estimated annual recurring cost of $65,000 thereafter." Allen described as "somewhat controversial" the "relative value of the Jackson et al. property." The local historical society's purchase option of $115,000 expired on March 31, 1961, making its current value about $257 per acre. "Perhaps not pertinent, but at the same time somewhat startling in comparison," said Allen, "is the reported $30 to $50 per acre valuation of adjacent good grazing land; " an amount only 11 percent to 20 percent of Mrs. Jackson's asking price. "We cannot anticipate [the Jacksons'] reaction should the appraised value be less than $257 per acre," said the SWR director, "although it is known they feel the property to be worth much more. "What Mrs. Jackson hoped to accomplish in the sale to the park service was recapturing not only the $25,000 paid by her late husband to "Mac" Sproul in 1946 for the property, but also "close to a quarter-million dollars" for "fencing, some restoration, the construction of facilities, utilities, and roads, and . . . losses suffered in such unprofitable ventures as a boy's camp." [53]

As if money were not enough of an obstacle at Fort Davis, Allen reported to Washington headquarters that the study group, even though it spent only a short time in the "rather remote west Texas town of Fort Davis," learned that "no great or overwhelming amount of public interest in, or support of, the Fort Davis National Historic Site proposal was detected among the local population." Utley and his colleagues had heard rumors that "some confusion existed among some of the Fort Davis Historical Society members as whether they favored Federal or private ownership of the fort area." While there were proponents like Barry Scobee, failure to achieve strong community backing would make the high cost and duplicative historical nature of the site hard to sell to Congress, unless changes occurred in Washington in the elections that November. [54]