|

Fort Davis

A Special Place, A Sacred Trust: Preserving the Fort Davis Story |

|

Chapter Four:

Shaping a Visible Past: The Five-Year Plan of Historic Preservation, 1961-1966

The signing in September 1961 of legislation creating Fort Davis National Historic Site constituted the first half of the journey for revitalization of the abandoned military post. Before Lady Bird Johnson could grace the platform at the dedication ceremonies in 1966, NPS officials and supporters labored for five years to develop strategies for restoration of buildings, hire staff, implement policies and guidelines, and convince the surrounding community of the importance of park service programs to their lives. For Fort Davis, the historic site had not only the backing of many political sponsors, but also the good timing that Michael Kammen found critical to park survival in the 1960s. "Between 1961 and 1979," said the historian of American cultural memory, "the federal government became principal sponsor and custodian of national traditions." Yet within these two decades, "[there] began a process of fiscal and administrative retrenchment that has continued ever since." [1]

Such considerations were on the minds of park service personnel throughout the five years dedicated to the planning and implementation of the $1 million restoration and stabilization program at Fort Davis. They and their local partners in west Texas knew only too well of concerns about the coercive power of the federal government, not to mention its taxes and regulatory demands. The NPS also had to contend with national forces in the first half of the tumultuous decade of the 1960s: race, ethnicity, antiwar sentiment, and growing disaffection with the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, whose support of Fort Davis had made its high level of funding possible. Yet the chance to work on a park that Franklin Smith, superintendent from 1965-1971, called the "last of the old parks," because of its "touch of the romantic," proved spellbinding for NPS officials eager to work on the story of the frontier West and its Indian wars. [2]

Even before the arrival in Fort Davis late in 1962 of the first superintendent, Michael Becker, the Park Service and its parent, the Interior department, learned of the expectations and controversy that the historic site would generate throughout the first thirty five years of its existence. A "Miss Virginia M. Stallings" wrote to the Senate sponsor of the park legislation, Ralph Yarborough, in November 1961 to complain about a rumor that she had heard about waste in the Park Service. Miss Stallings asked the whether NPS planned to "entertain proposals to demolish any of the historic structures comprising Fort Davis." This was in addition to a story that Interior sought to "expend $3,000,000 for a grass growing project in the desert [she did not say where]." John A. Carver, assistant secretary of the Interior, thus had to release the first of many letters of correction to critics of the NPS. Carver informed Senator Yarborough that not only did the Park Service not intend to destroy the buildings at Fort Davis (nor grow grass in the desert), but that "it has been our experience frequently that after the Congress has authorized the establishment of a new unit of the National Park System rumors of various sorts, often unfounded, are circulated." [3]

More thorough was the inquiry of Dale Walton, state editor for the San Angelo Standard-Times, who asked SWR's Erik Reed in March 1962 to provide information about the status of the park. Walton apologized for not knowing more about the plans of the Park Service, and reminded Reed that "we have a prime interest in the fort and the town and would like to get started with stories on work there." Reed sent Walton a copy of Bob Utley's 1960 "area investigation report," and noted that until the NPS purchased the land from Mrs. Jackson, "I cannot give you a precise forecast of future activities at Fort Davis." The regional chief of interpretation did, however, reveal that the park service had asked Congress to include in its fiscal year 1963 budget $395,026, which "would provide for the purchase of the property and for staffing the area with essential personnel." In addition, the SWR could then "launch the first year's work on stabilization and restoration of the historic structures, and begin the construction of roads and trails, visitor center (museum and park headquarters building), employee residences, and utility structures." Construction would be designed and managed by the NPS, but private firms would receive the contracts for the actual work. Reed did not anticipate charging admission fees (one of Walton's queries), as it was not NPS policy to do so "at areas of the size and character of Fort Davis." The regional office, however, "would appreciate receiving copies of any articles [Walton] may write on Fort Davis," and Reed looked forward to working with the San Angelo paper in the promotion of the newest park in west Texas. [4]

Curiosity and confusion about Fort Davis reached the highest levels of the park service that same week in March 1962 when Frank Masland, a member of the Interior Secretary's Advisory Board from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, wrote to his friend "Connie" (Conrad) Wirth, NPS director, about his recent trip to the Davis Mountains. Echoing a sentiment of many easterners, Masland found the area "beautiful," and thought that "they would probably qualify as a National Park." But in his "humble opinion, Old Fort Davis doesn't qualify for anything." As a staunch conservationist, Masland considered the stone and adobe structures to be "a mongrel bunch," and "it would appear that some of them are being lived in." He then criticized the elaborate plans made for Fort Davis: "The lay of the land is such that if with a considerable expenditure of money buildings could be restored and/or stabilized and the place cleaned up, there would, I think, be little visitation and less reason for it." Wirth's friend then suggested that "it would not be simple to lay out a program for visitors," since "the buildings are scattered over too wide an area." Instead Masland hoped "that if there is public pressure for Service acquisition it can be resisted." [5]

The bluntness of Masland's letter required a diplomatic response from the NPS director, who thanked him for his "views" and could "appreciate that in [Fort Davis'] present condition it may not have impressed you favorably." Wirth expected that passage of the 1963 park service appropriation bill "will provide funds for land acquisition there and some money to begin a program of stabilization of the structures and ruins." The director then hoped that Masland would "change your mind about Fort Davis when you see it again . . . after we have had a chance to improve conditions there." Wirth saw in Fort Davis "a long and fascinating history in the story of the southwestern frontier." The park service stood committed to "bring this out in our development," and he took pride in the fact that "the people in Texas are enthusiastic over the prospects." [6]

The long-awaited congressional funding arrived in October 1962, which permitted the NPS to approach Mrs. Jackson with an offer to purchase her property. When Barry Scobee received word of this action, he wrote to Conrad Wirth in December 1962 asking advice about the promise made by the Fort Davis Historical Society (FDHS) to contribute whatever funds it had towards the acquisition of park land. The amount stood at some $5,000, and Scobee wondered if this could be applied to another project since Congress would now meet Mrs. Jackson's quote. What the venerable historian of the Davis Mountains sought was use of the money to publish his manuscript on Fort Davis and the surrounding territory. Wirth considered it "an advantage to have a book on Fort Davis, such as yours, available for the public as soon as possible after the historic site is established." The park service would be several years away from producing its own text on Fort Davis. To that end, Wirth instructed SWR's Bob Utley "to assist [Scobee] in any way possible if you have any questions concerning format or historical procedures in publications." [7]

Appropriation of Fort Davis monies in late 1962 also permitted the park service to advance the work of Bob Utley along two tracks: the development of the historic structures report (so that construction could begin the following spring); and the collection of historic data for use in the new museum and visitors center complex (itself the target of early construction work). Michael Becker remembered how Utley's professionalism influenced the quality of the work. Utley, in Becker's words, was "very thorough," and provided the superintendent much "useful information." Becker had come to the park from his first superintendency at Tumacacori National Monument in Arizona. He had never heard of Fort Davis, but realized soon thereafter that a combination of regional and Texas political interest in the site made it a special place. Becker would later call Fort Davis his "best job in 30 years in the park service," in part because of its high profile and because of the chance to build a park from the ground up. In addition, the lack of new park formation in the 1950s had meant few career moves for park rangers. By 1960, said Becker, 80 percent of rangers had "hit their peak." Fort Davis allowed him to move upward from Tumacacori, and he knew at the time that "few superintendents get that experience [where] everything jelled." [8]

|

|

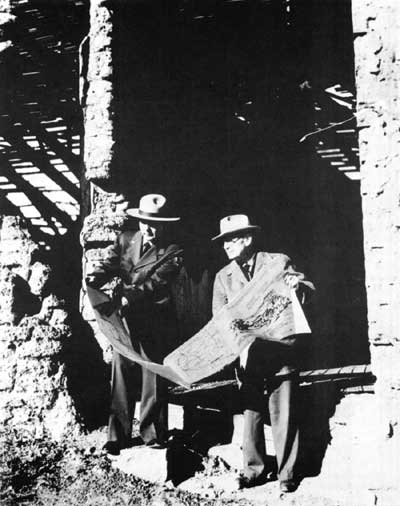

Figure 17. Superintendent Michael Becker

and Barry Scobee reviewing Master Plan (1963). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

One reason that "everything jelled" at Fort Davis was the unification of historical research by Bob Utley, both for the historic structures and the visitors center/museum complex. In the summer of 1962, Utley combed the files of the National Archives in Washington to prepare both documentary and photographic evidence of the existence of the old military post. Thomas J. Allen, Utley's boss at SWR, informed the chief architect of the park service's Western Office of Design and Construction (WODC) that Utley had run into delays because of the distinctive nature of Fort Davis research. "The guidelines for preparing historic structures reports were designed for the problem of a single building," said Allen in September 1962. Fort Davis compounded this situation because "we have more than fifty historic buildings or sites of buildings, about half of which are represented by standing structures or remnants of structures." Utley had also discovered that "the documentary material on Fort Davis located in the National Archives has significant gaps that complicate the task of preparing the historic structures report." For these reasons, Allen suggested that Utley travel to San Francisco to discuss the Fort Davis plan with Charley Pope the historical architect of WODC, and then to write his draft based upon the linkage of the concerns of the NPS' architectural and historical offices. [9]

Upon Utley's return to Santa Fe from consultations with San Francisco NPS officials, he realized that Fort Davis' lack of staff and management would hinder standard park service strategies for supervision of construction work (especially given the project's isolation from other NPS sites, and the high volume of work to be undertaken). In addition, Utley had not completed all his own historical research for the museum. James M. Carpenter, acting SWR director, told WODC officials in November 1962 that work needed to begin as soon as practicable on the overhanging porches to protect the facilities on officers' row, but that private contractors could not be left alone on site to complete the task, for fear that "it would not be given the consideration that the historic structures deserve." Sanford Hill, chief of WODC, added to the sense of urgency by noting that "our plan for the Southwest Region this year consists entirely of the work at Fort Davis." He wanted to transfer to Fort Davis on or about January 1, 1963, a staff architect to oversee plans for "immediate support and shoring of walls, roofs and grounds to preclude further deterioration." Such a person could then prepare additional historic structures reports for later phases of stabilization, "supervise any necessary Day Labor and Contract work," and draw blueprints for "reconstruction of the Barracks Building No. [20] which probably will be restored as a Visitor's Center and Administration Building." The fact that Fort Davis had $40,000 available for construction work appealed to Allen and Hill, and the two discussed how to move the project forward without having to send everything to the central office in Washington. [10]

The arrival of Utley's reports in regional and WODC offices allowed its supervisors to comment upon the unconventional strategies suggested for such a park as Fort Davis. A. Clark Stratton, assistant director for design and construction in Washington, praised Charley Pope's original concept of overhanging porch roofs. "The proposal to protect the buildings surrounding the parade ground by means of limited restoration consisting of new roof structures and porches which will return the buildings to their original image," Stratton told the SWR director, "is considered here to be a desirable and welcome departure from past practices." Robert Utley remembered Pope's design as "revolutionary and brilliant," especially in light of Region III's focus on archeology over history. Stratton also declared Utley's report an "excellent . . . framework for consideration of the treatment of Fort Davis as a whole." Stratton's only reservation was the call for rehabilitation of the post hospital, which he saw as "not as defensible as are the other proposed restorations." Roy Appleman, Washington office (WASO) staff historian, concurred in Stratton's judgments, calling the hospital "a major financial undertaking, together with its subsequent furnishing and maintenance." Appleman favored "retaining the hospital as a ruin, giving it treatment similar to other buildings of this character in the Fort area." The WASO historian then went beyond Stratton's comments to suggest that the visitors center (which he agreed should be housed in the barracks building) be modeled upon Homestead National Monument, in Beatrice, Nebraska. Homestead had "large wall historical murals which reflect the theme for the place." A staff historian could be dispatched to Homestead, said Appleman, to devise a similar depiction for the visitors center at Fort Davis. [11]

Throughout the spring of 1963, NPS devoted more attention to the implementation of the design plans crafted by Bob Utley, Charley Pope, and others of the park service. When Superintendent Michael Becker reported for duty on January 6, 1963, he faced the need for employee housing, although he only had funds that winter for an historian and a supervisory park ranger. The slots for secretary and maintenance chief would soon follow. Because of the limited housing availability in Fort Davis (described by SWR director Thomas Allen as "sub-standard"), and the need to have some custodial personnel on or near the grounds at all times, the park service agreed to design employee housing in the spring of 1963. Becker and his wife had chosen to take a rental on the Mexican east side of Fort Davis; a situation that raised eyebrows among the Anglo establishment of the town. More challenging to the status quo, and an indication of the impact that the park service would have on community sentiments, was Becker's attendance at the Catholic church, making he and his wife the only Anglo parishioners that anyone could remember. [12]

This action by Becker came at a time when the community of Fort Davis struggled to understand the type of individual coming to work at the park, and also the lifestyles that they had cultivated in areas more urban than the Davis Mountains. Becker recalled that his offer of a secretarial position to Etta Koch was accepted immediately, as she had worked for 13 years in the office of Big Bend National Park. The superintendent had little control of one hire: that of the historical architect, Charles Woodbury, assigned to Fort Davis by the San Francisco WODC. Woodbury proved to be a most colorful character; perhaps too colorful, in the words of Bob Utley and other park service officials working on the design of the site. Woodbury had been divorced, had brought to the strict Protestant community a girlfriend with whom he lived, and suffered from alcoholism. Erwin Thompson, Becker's first hire as an historian at the post, remembered that Woodbury had to leave Fort Davis within five weeks of his arrival because of an incident in town one night. After drinking too much liquor (which was hard to procure in a "dry" town like Fort Davis), Woodbury drove down the main street of town at midnight, and then onto a sidewalk. The local sheriff had to arrest Woodbury, incarcerate him overnight, and contact the park to have the architect released on bond. When Thompson went down to the courthouse to inquire about Woodbury, the sheriff noted with some amusement that the NPS employee had been the "first white man ever kept in the local jail." [13]

Where the arrest of Charles Woodbury within weeks of the arrival of NPS staff surprised the local community, the hiring by Michael Becker of Pablo Bencomo as the first chief of maintenance demonstrated that a new social order had come to Fort Davis. The position would be one of great importance to the park service, as the maintenance chief would have to hire and train workers able to meet NPS policy guidelines that exceeded most of the criteria for electrical, plumbing, carpentry, and stone work of the surrounding area. In addition, the park service would pay national wage scales, offer opportunities for training and promotion, and perhaps most important, would pay health and vacation benefits not usually offered by local ranchers and contractors. Interviews with Bencomo's co-workers 30 years later revealed the depth of their respect for his abilities, and for his courage in challenging the racial barriers in Fort Davis. Bencomo, a war veteran and, in the words of seasonal ranger John Mitchell, "the best carpenter in town," had applied for the position after reading about it in the local newspaper. Once Bencomo became the maintenance chief, said Becker in his first monthly report as superintendent, local Hispanic workers poured into his office seeking employment. "There were at least ten to twenty men for each position on the initial [maintenance] crew," Becker wrote in January 1963, and he attributed this successful canvassing of the community to the presence of Bencomo, whom Becker himself described as "the local contractors' top hand." [14]

With good staff and maintenance workers on site, Becker could then discuss with regional and WODC personnel the first phase of actual construction: the six adobe buildings along Officers' Row. Becker agreed with Pope that the best technique would be to place "bond beams" around the roof of each structure upon which to hang the porches. The construction firm of Hal K. Showalter, of Midland, Texas, was thus awarded the first large restoration contract at Fort Davis, to the tune of $59,000. Unfortunately, another bidder, the Robert L. Guyler Company of Lampasas, Texas, protested the award, forcing Becker and the regional office to investigate. Guyler eventually received the "roofs and porches" contract, and the first of many construction crews descended upon Fort Davis to begin the million-dollar project to revive the historical past. Soon thereafter, Becker sought to initiate work on the visitor center/museum complex, but realized that this would take some 15,000 adobes (which were not readily available in the Fort Davis area). Becker remembered from his days at Tumacacori of the adobe makers in the Tucson area, but learned that "the freight rates [from Arizona or New Mexico] make the importation of stabilized adobes . . . impractical and financially objectionable." Thus he asked the regional office for permission to manufacture the mud bricks on site; a situation that would delay work on the visitors center until the fall of 1964 at the earliest. [15]

Adobe construction in the Fort Davis area, while common in the nineteenth century, had given way to stonemasonry or frame construction. Thus the regional office expressed concern about the request, especially in light of criticisms of the technique of "stabilizing" the mud brick with concrete injected into the adobe before drying. One concern of WODC was the fact that the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), which would insure any structures at Fort Davis, wanted assurances that the bricks would not melt before agreeing to underwrite a 30-year loan. Jerry A. Riddell, chief architect for WODC, wanted Superintendent Becker to conduct his own tests on the bricks made on-site, looking for their reaction to "compressive strength, shear, and resistance to moisture." Becker had ordered adobes made in Presidio, Texas, but Riddell wondered if they could endure the demands of park service visitors and maintenance standards. [16]

By the end of the first summer of operations at Fort Davis, Superintendent Becker had a good idea of the scale of work to be done in restoration of the historic buildings, as well as the development of a network of utilities and park service structures for the daily activities of the site. In March 1963, the SWR had completed its "five-year plan" for Fort Davis, calling for accurate and thorough attention to historical detail in all work. Superintendent Becker reported in August that criticism had already begun about the ambitious and costly program for the site, noting that "a rather conservative Australian visitor walked into HB [Historic Building] #2, and before saying Hello he blurted out, "I certainly wouldn't vote for a senator who would appropriate $1,000,000 for a place like this." Becker and his staff understood this type of comment, as the regional, San Francisco, and Washington offices devoted what seemed to be an inordinate amount of attention to the details of the master plan. One example was the decision by the regional director, Thomas J. Allen, to locate the paved entrance road through the cottonwood grove to a parking area south of the planned visitors center. Allen and the NPS planners also wanted the housing compound placed next to the maintenance yard, creating problems of privacy for employee families and requiring landscaping along the highway to camouflage the non-historic structures (which originally were to be made of adobe). [17]

Whatever the degree of higher-level NPS control of Fort Davis planning, Superintendent Becker and his staff could not be influenced by such comments. They instead moved to address questions of worker and visitor safety, water supply, and electric power. One request made by the superintendent was "the reestablishment of the dike system which was initiated during the Army days at Fort Davis." The new historic site, like the old military post, needed protection from drainage down from Hospital canyon. A series of lateral canals would carry water away from the new buildings, and would "control and prevent accelerated erosion of the lands of the Park Service." Water supply and use also concerned the superintendent, who discussed the issue at some length in October 1963 with D.W. Geisinger of the WODC. Geisinger had studied the options at the park service's disposal relative to the site's access to potable water. He concluded that "a water supply providing a steady supply of 3 gpm [gallons per minute] or 9 gpm based on an 8 hour demand day will satisfy domestic future water demand for the next 20 years." At that time the park utilized a well some 300 feet west of the officers quarters, and Geisinger reported the existence of "another well believed to be a good source of water . . . located next to the old church camp site near the head of Hospital Canyon." These wells, if drilled deep enough, could supply Fort Davis with sufficient water for staff, park maintenance, and the new compound of employee housing under consideration, as well as Geisinger's projection of 100,000 visitors annually by 1985. [18]

When Becker approached local utility companies for advice on the water system, as well as electrical power, they did not show much enthusiasm for working with the park service guidelines that required underground routing of pipes and wiring. The distance from the reservoir to the central buildings of Fort Davis also presented problems of cost, as WODC wanted a six-inch water line run underground. Above-ground construction would not only require less labor, but maintenance would be easier. The historic character of the post would be affected adversely, however, with visible power lines and electrical wires; a situation that Becker suggested could be mitigated if NPS built "spur lines for the installation of the fire hydrants and hose houses behind the various buildings on both sides of the parade ground." In similar fashion the park service could install additional electric transformers behind the historic structures to limit the need for an elaborate wiring grid exposed to public view. [19]

|

|

Figure 18. HB-2 (Ranger's Office) with

storm damage (May 1963). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 19. Front view of HB-2 (Ranger's

Quarters) (April 1963). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

On the heels of Geisinger's water and power report for WODC came Ronald F. Coene of the U.S. Public Health Service in Dallas. On April 2, 1964, Coene visited with Superintendent Becker and his chief ranger, Robert "Bob" Dunnagan, to draft the site's first "environmental health survey." Having had the experience of one year's construction work and visitation (a total of 64,321 persons from January to December 1963), Coene expressed satisfaction with conditions as he found them that spring. He noted that of the six permanent and 12 seasonal employees, only one lived on the grounds (in one of the officers' quarters). Renovation of the various historic structures would provide "only for protection against the elements and will not be used to house anyone, nor will visitors be able to enter them." Coene did warn against the presence of polluted water in wells around the historic site, given the lack of sewage treatment in the Fort Davis area, and he advised Becker to install chlorine treatment equipment as soon as possible. He also suggested abandoning the traditional practice of draining sewage into cesspools, as these would only negate the impact of the chlorination. The public health officer's findings validated the concerns of Superintendent Becker, whose discovery of coliform bacteria in the park's water supply had required him to accelerate the planned 1966 environmental survey to address the real threat to staff and visitors. [20]

The historic structures rehabilitation moved forward quickly in the spring and summer of 1964, drawing much praise from local visitors who marveled at the extent of park service design and construction. Thomas N. Crellin, the historical architect who replaced the controversial Charles Woodbury, prepared a series of reports that commented at length on the original plans and specifications. In May 1964, Crellin offered his advice on the status of rehabilitation work, based upon the same 12-month experience that D.W. Geisinger and Ronald Coene had used to craft their reports on water and power. The first winter of visitation and park service habitation at the site revealed the need for better heating, especially use of oil and electric heat, rather than the first estimate that butane gas would be sufficient. This would then require more heating ducts and redesign of ceilings and walls to accommodate the new piping. Crellin also warned against too much reliance on wooden flooring, as the weight of visitors crossing them could wear them out earlier, thus costing even more money in maintenance and repair.

The historic architect saved his most pointed comments for the process of adobe brick construction underway at the site. "I would question the use of stabilized soil as a surfacing material for the porches," said Crellin. "Judging from the quality of the soil-cement blocks produced here," Crellin told his superiors in Washington, "I doubt that a surface of sufficient hardness could be produced to hold up over an extended period of time." The historic architect conceded that stabilized soil "is used for road surfacing and is placed with optimum moisture content and maximum density." He countered with the argument that "foot traffic tends to follow definite patterns and to concentrate particularly at openings, resulting in severe localized wear." Crellin instead opted for "an integrally colored concrete slab" to "give the same general appearance;" a circumstance in keeping with NPS historic preservation policy since "a soil-cement mixture would require a color additive also." From this would come "a better surface," as "most of the commercial coloring agents contain a surface hardener." [21]

|

|

Figure 20. Early staff (left to right): Bob

Dunnagan, Erwin Thompson, Tom Crellin, Etta Koch, Michael Becker

(Superintendent), and Pablo Bencomo (1963). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

The NPS western office of design and construction then weighed in with their comments on the progress of rehabilitation in June 1964, as the fiscal year drew to a close and funding for 1965's activities drew near. Daniel B. Beard, SWR director, wrote to WODC that month to declare that the pace of work indicated a completion date sometime in fiscal year 1967. In order to meet that deadline, Beard's staff needed to rethink certain assumptions about work and funding. One area of concern had become the post hospital (HB46), which in the original master plan had been targeted for "complete restoration" at a cost of $57,000. The SWR director reminded the chief of WODC that "the Washington office questioned the desirability of completely restoring the hospital," while SWR and park personnel "thought the money might better be used to reconstruct the cavalry and quartermaster corrals." Beard reiterated the opinion of his staff that "this alternative would be a much less ambitious project, [and] would afford additional features of a side of the parade ground not well represented by historic remains and thus visually out of balance." In addition, this shift of funds "would provide a place to house large display items such as the ambulance recently acquired." The hospital could then be "roofed and porched in the same manner as the officers quarters," resulting in financial savings and more rapid completion of the overall rehabilitation of the post. [22]

|

|

Figure 22. Superintendent Michael Becker at

HB-30 (Guardhouse) restoration (September 1964). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 22. Commissary restoration (HB-21)

(1960s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

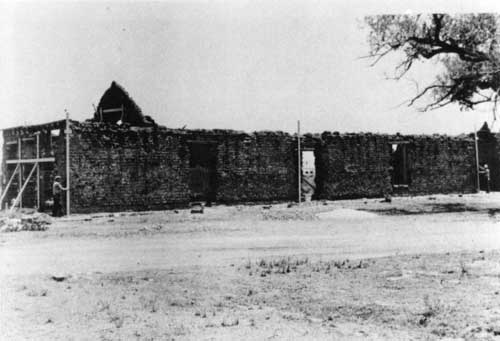

Figure 23. Ruins of HB-21 (Enlisted Men's

Barracks) (August 1964). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 24. HB-9 (Officers' Quarters)

(August 1964). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

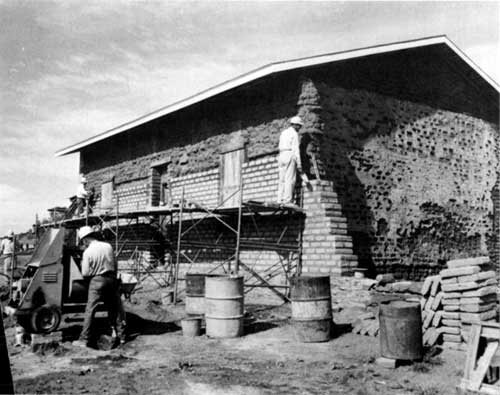

Figure 25. Scaffolding for masonary work on

HB-46 (Post Commissary) (September 1966). Courtesy Bob Crisman. |

|

|

Figure 26. Military Cemetery (September

1966). Courtesy Bob Crisman. |

|

|

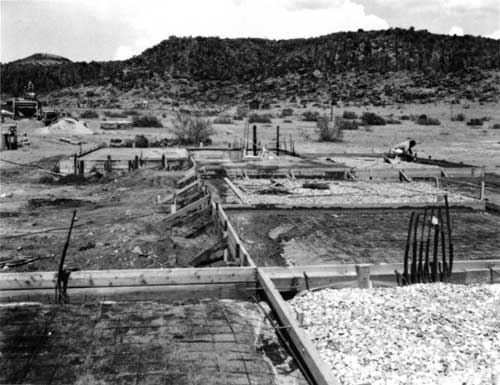

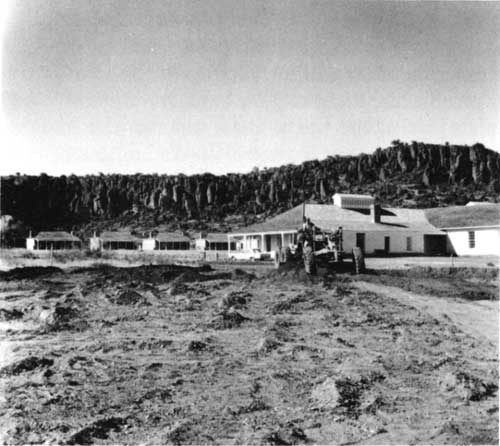

Figure 27. Construction of employee housing

campground with Mission 66 funds (1965). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 28. Repointing stone on chapel

foundation (November 1967). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 29. Chapel stabilization work

(October 1968). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 30. Wall collapsing at HB-46

(Hospital) (July 1967). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 31. Demolition of private museum

operated by Fort Davis Historical Society (1966). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 32. View of two-story officers'

quarters across parade ground through window of Hospital Steward's

Building (1960). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 33. Restoration of freight wagon

wheel (1960s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

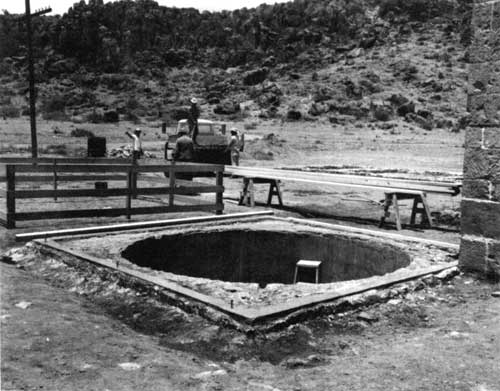

Figure 34. Excavationof Cistern behind HB-7

(Commanding Officer's Quarters) (1960s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

The regional director's thoughts on the hospital prompted Superintendent Becker to begin a process of discussion about the facility that would endure for the next three decades at Fort Davis. He concurred in Beard's suggestion that the post hospital not receive such elaborate treatment as first planned. Funds saved from the hospital project should be redirected to the "restoration of the quartermaster corral," as this would generate storage and display space for the historic artifacts being acquired. The structures around the corrals would also "fit into the interpretive picture much better." Becker then turned to another building included in the master plan: the post chapel. "Since my arrival here," said the superintendent, "I have given considerable thought to the parade ground illusion of 1880, and while I did not feel at first that the chapel should be restored, I feel strongly, both from a local public relations standpoint and from the visitor's visual standpoint, that the chapel should be reconstructed." The superintendent wanted "essentially the same type of thing that we have on Officers' Row -- an exterior restoration only." Becker envisioned only rebuilding the four walls, which would not require "extreme expense." He also believed that "the visual picture would be improved a great deal if we were to do an exterior reconstruction." [23]

Nagging at Superintendent Becker in the winter of 1964-1965 was the sense that the original enthusiasm for rehabilitation at Fort Davis had slowed. On January 28, 1965, he and SWR historian William "Bill" Brown coauthored a memorandum to the regional director criticizing what they considered the "bogging down" of the five-year plan. Two factors contributed to this process of delay: "insistence by WODC that the strict letter of the Historic and Prehistoric Structures Handbook be followed without variation or reasonable compromise;" and the "assignment by WODC of the Fort Davis architect to other projects." Becker and Brown painted for the SWR director "a grave picture in terms of area development for visitor use and enjoyment, and a huge carryover of unobligated funds" resulting from the slowdown. As evidence they cited the inability of architect Crellin to complete his design for HB7, the commanding officer's quarters, which they described as "the key structure in Officers' Row, which, in turn, is the core of the site and the prime visitor attraction." Crellin had to spend two days per week at Big Bend National Park, and Fort Davis had other reports needed from Crellin prior to commencement of construction. Compounding this was WODC's demand that each structure have its own report prepared, despite the similarity of work planned for each building along Officers' Row. Becker and Brown predicted that, "in the long run, [this] would mean many years' delay in completing this superficial and simple job" of "installation of historic doors, windows, shutters, and porch railings." [24]

If the construction crews at Fort Davis had to halt their work on procedural grounds, Becker and Brown warned that visitors would see not "an operating historic site" but "one shambling indefinitely through the scrap-lumber of becoming." This would inevitably raise questions of expenditure of public funds. The report noted that Fort Davis had already fallen behind in fiscal year 1964 spending, leaving $35,000 in work undone. Should the NPS hold back construction work authorized for fiscal year 1966, Becker and Brown saw a new carryover of $70,000. "It is unnecessary to dwell on the evils of large unobligated balances," said the two officials, "except for this comment: Fort Davis will soon have passed through the new-area honeymoon." Failure to "get cracking" on the restoration program at the site suggested that "Congress might view [Fort Davis] with alarm, and shut off this rathole." They predicted that the historic site, begun with such fanfare, would become "a half-finished area struggling along for years toward a semblance of completion against the dual handicap of inadequate funds and deteriorating structures." Becker and Brown then concluded by requesting of SWR that WODC send immediately a full-time architect to complete plans for the visitors center, employee residences, and enlisted men's barracks (HB21); and to "allow the Park to prepare a special Part II [historic structures] report covering installation of historic doors, windows, shutters, and porch railings for all 13 structures on Officers' Row." [25]

By the spring of 1965, the stalemate on historic structure design at Fort Davis had eased only somewhat. Thomas Crellin was asked by WODC to offer estimates on the amount of time necessary to complete plans and specifications on four buildings: HB14 and 15 (two-story officers quarters); HB 39 (the granary); and HB37 (the commissary). Crellin considered these buildings as "in the best condition for restorative effort," and he anticipated that he would need some 640 hours of work (or four months) for their design. He could not guarantee when he could address the hospital (upon which he had already spent four weeks), or the chapel, barracks, magazine, and quartermaster corral. Because of this time constraint, Crellin echoed the sentiments of Becker and Brown that the Officers' Row facilities be unified in their research and design. Even with this reduction in time, the structures would require some 1,000 hours of research and drafting of plans (or six months' labor) by the historic architect. "It should be recognized," said Crellin, "that the conversion of Fort Davis into a restored entity cannot be accomplished overnight." He reported that "much favorable comment has been offered regarding the degree of progress already made," and the completion later in 1965 of the barracks buildings would satisfy many critics. Crellin did warn his superiors: "That the historic structures program at Fort Davis may be a continuing thing for more than a generation is not unrealistic." It was his hope that "future generations may well feel that the history in our heritage is worthy of further development." Hence the NPS architect saw it as "incumbent on the present to record as faithfully and as completely as possible every detail that may be of value to the future." [26]

The historic architect had the opportunity to influence regional opinion on Fort Davis when in late May 1965 the next superintendent, Frank Smith, came to west Texas to observe his new post prior to leaving SWR as its curator of museums. Smith, an anthropologist and music lover from Pueblo, Colorado, and Crellin agreed that "there's [design] work for three or four men, and Tom has one body, one pair of arms, and can occupy only one location at a time." WODC decided to send to Fort Davis a supervisor for the ongoing contracts, plus a draftsman for future work, and SWR accepted Superintendent Becker's call for a joint historic structures report on Officers' Row. These agreements were prompted by regional director Daniel Beard's growing concern about the costs of work at Fort Davis. "I believe we may face a serious situation," he told the chief of WODC on May 27, 1965, "because Congress has indicated again and again that it does not want to spend much money on restorations." Beard called upon WODC to assist the region to stay on the five-year plan, and to "complete the next stages of the development rapidly and economically." [27]

No sooner had Beard and Becker established the working relationship that they hoped to pursue with WODC than did the San Francisco office challenge certain elements of the accelerated design program. Jerry Riddell of WODC saw shortcomings in the January 1963 "interpretive prospectus" drafted by Bob Utley; the document that had been the basis for Tom Crellin's planning. Frank Smith told Beard soon after his arrival at Fort Davis that "WODC (and specifically Charlie Pope, I guess) continue to scream about the combined reports on the officers' quarters." The new superintendent decided that it would not be worth the trouble to fight San Francisco, as he already had contractors at work on the quarters. Smith then addressed the controversy surrounding the post hospital and chapel. As to the former: "In spite of a firm conviction about the separation of Church and State, I agree with Mike [Becker] that we should revise the prospectus to include exterior reconstruction of the post Chapel." Smith also agreed that "WODC's feeling for the hospital is well based," and urged the SWR director to "meet [WODC] half way and let Crellin complete this report." [28]

Beyond the concerns that NPS officials had for the historic structures at Fort Davis, the second area of focus was the landscape planning and grounds maintenance. Pablo Bencomo remembered in 1995 how the old parade ground had been covered with yucca (soap tree cactus) because of the neglect over the years by the caretakers for the Simmons/Jackson family and the James family before them. Ralph Russell, principal of the Anderson elementary school next door, and a seasonal ranger intermittently from 1973-1988, also recalled that the grounds were infested with the "cat's claw" plant brought in by the grazing of sheep, and the cottonwood grove had become choked with underbrush in the dry years of the 1950s. Local children would play in the pools of rainwater that collected in Hospital Canyon after a storm, and they called the area the "Devil's Sinkhole" for the erosion along the streams. Russell, who would specialize in research on the plant life of the site while a summer hire at Fort Davis, told of the overgrazing that destroyed much of the native vegetation, and of efforts by the NPS staff to bring some of these plants back to life. [29]

The first year of park service management of the property taught valuable lessons to the staff about ecological change and continuity. In his monthly report for September 1963, Michael Becker noticed that "due to the numerous rains and no domestic stock grazing on the site we have an abundance of high grass." This plus the "lack of a sufficient water system to protect the shingled roofs which are now in place" threatened the park with an increased danger of fire. Then in March 1964, the high grass lured the sheep of Dude Sproul down from his leaseholdings in Hospital Canyon to graze along the boundaries of the historic site. Nonetheless, Pablo Bencomo, his maintenance crew, and the chief ranger addressed problems of tree removal, deposit of soil unearthed in the restoration of ruins and old buildings, planning for nature trails, and wildlife research and sightings. The alteration of the grounds (especially the turning of so much earth) tempted visitors to search for artifacts of the old military posts. Superintendent Becker thus reported in September 1963 that "the collection of artifacts and natural objects by visitors" constituted "our most prevalent offense." He believed that "an educational program should be intensified to help the public better understand why the Antiquities Act [of 1906] is enforced in areas of the National Park System." [30]

Another aspect of NPS concern about the environment of Fort Davis was the mandate for nature trails at park sites. In the spring of 1964, Pablo Bencomo and Bob Dunnagan designed and built a trail for visitors that ran along the north ridge of park property. They also utilized the services of Dr. Barton Warnock, chairman of the biology department at Sul Ross Teachers College, who identified some 30 plants along the trail. The following year the state of Texas division of parks approached Fort Davis with plans to link their hiking trails with the north ridge route. This enhanced the appeal of Fort Davis to the growing legions of outdoor recreation enthusiasts; a situation made even more attractive in the fall of 1965 when the park service agreed to close the "unhistoric parade ground road that formerly passed by the Nature Trail sign." Visitors now would leave their vehicles in the new parking lot, explore the grounds, and then have the opportunity to hike the hillsides around the fort without the intrusion of automobile traffic that detracted from the serenity that the park could offer. [31]

|

|

Figure 35. Construction of parking lot;

Visitor Center on right (November 1965). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

As Fort Davis neared completion of its first phase of historic structure research and planning, so too did the park face a growing need for accurate documentary research to prepare its museum exhibits and interpretive programs for visitors. Because the site commemorated the traditions of the frontier military, Robert Utley devoted much of his time to collecting documents and conducting interviews to make the park historically accurate in structure and interpretation. Utley saw in Fort Davis the opportunity to fulfill his own interest in the nineteenth century Indian-fighting army; a theme that had been ignored by his peers in the Southwest region, as they were influenced by the Santa Fe office's proximity to parks focusing upon precontact Native archeology, or upon Spanish colonial history. Utley also recounted in 1994 that few scholars in the 1950s showed much concern for the story of Fort Davis. Fortunately the attraction of the buildings, grounds, and ruins of the site drew to it top officials like Tom Crellin, Frank Smith, Utley himself, and Nan V. Carson, the furnishing specialist from the NPS' Midwest Regional Office in Omaha, Nebraska, who had researched the displays and exhibits at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Then, too, Utley would suggest as hires for the position of park historian individuals who went on to prominent careers in the service, such as Jerry Rogers, first employed in 1964-1965 as a seasonal historian and who later became director of the NPS's historic preservation program in Washington, and in 1995 the director of the Southwest region; Ben Levy, historian at Fort Davis who also followed Utley to the Washington history office; Erwin Thompson, who left Fort Davis after two years as park historian (1963-1965) to work in Washington, and then went to Denver in 1972 to become part of the inaugural staff of the Denver Service Center (DSC); and David Clary, a seasonal employee at Fort Davis who went to Washington as a career historian. [32]

|

|

Figure 36. Completed parking lot of Fort

Davis (April 1966). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

The excitement of tracing the West's military past at Fort Davis thus served as a strong attraction for park service personnel, but interpreting that for the average visitor in the 1960s presented problems not unlike those surging through the nation's classrooms and media outlets. Issues like racial equality competed with the public desire for fond memories of the Old West; a situation compounding Fort Davis' multicultural history. The presence of women and families at the post in the nineteenth century would bring gender differences to the planning and research phases. Then too, the ongoing conflict in the jungles of Vietnam changed public attitudes about the military, polarizing opinion around the devastation that war brings to society. The isolation of Fort Davis, and its place in Texas frontier lore, spared it from the worst of the academic and popular debates about American racism and conquest, but the search for data on the story of the post would engage these questions nonetheless.

For Robert Utley, the most critical feature of historical research was its application to the proposed visitor center and museum. Thus in December 1962, SWR director Thomas Allen wrote to the Western Museum Laboratory in Berkeley, California, to ask that Utley be included on the design team for Fort Davis. "The master plan and historic structures report," Allen told the chief of the NPS laboratory, "propose telling the story of Fort Davis' role in frontier defense in a museum in a barracks that will be restored for visitor center purposes and setting forth the story of life at Fort Davis in a restored squad room, officer's quarters, and hospital." Because of the heavy emphasis on historical accuracy, Allen argued that "approval of the master plan should precede any serious museum planning, for disapproval would mean a fundamental revision of present museum thinking." The regional director also noted that "there is the question of when the rehabilitation of the barracks for visitor center purposes will be completed." To that end, Utley's presence on any museum design team would help the region meet its own agenda for Fort Davis, which was influenced in great measure by the scale of restoration work on site and political interest in the overall project. [33]

By working with the museum staff of the park service, Utley could advance his own research and writing of the Handbook of Fort Davis, which appeared in draft form in June 1963. The regional historian wrote widely to archives, museums, and private individuals in search of materials that fit both the museum's needs and his scholarship. The most logical target for material collection was Colonel Benjamin Grierson, commander of the post in the 1880s who secured the appropriations to build the facilities that endured long after abandonment of the fort. Utley learned that Texas Tech University, in Lubbock, had microfilmed all 2,800 pages of the Grierson collection that had been housed originally in the Illinois State Historical Library. Utley also took interest in the most important of the campaigns based at Fort Davis: Grierson's search in the summer of 1880 for the Warm Springs and Mescalero Apache bands under the leadership of Victorio. He thus wrote to Ralph Smith, history professor at Texas Tech, in April 1963 to solicit information about the death of Victorio at Tres Castillos, Mexico. The regional historian wanted to depict the Grierson campaigns in the new Fort Davis museum, and asked Smith how he could contact Mexican historical agencies about Colonel Joaquin Terrazas, commander of the forces that killed Victorio. Utley also needed advice on creating an exhibit on "an Apache attack on a Mexican hacienda of the period around 1850, plus or minus fifteen years or so," and acquisition of "a detailed map [that] will show West Texas travel routes of the 1850s and 1860s." [34]

While Utley wanted to recount the military campaigns on the Texas frontier, he was also dedicated to historical accuracy that ran counter to the ethnocentric assumptions of many Americans. The regional historian and his associates at Fort Davis learned this early when in the spring of 1963 Utley started collecting information about the black cavalry and infantry units that comprised the bulk of the troops stationed at the post. He did not seek to cause controversy, as his letter of April 19, 1963 to the chief of military history in Washington indicated. Utley wanted only to have "color reproductions of the regimental crests of the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry" from the period of 1867-1880. Utley had no plans to depict daily life as experienced by young black males on the far western frontier, the racial tensions that their presence caused, the interaction between blacks, Indians, Hispanics, and Anglos, or of the denial of the historical reality of black defenders of the West in the nation's textbooks, films, artwork, or historical memory. [35]

None of this mattered to some visitors more comfortable with the racial separations prevalent in Texas or the nation prior to the turbulent civil rights era of the 1960s. T.E. Fehrenbach wrote in Lone Star that "in Texas, the black man faced a combination of class disadvantage, differentiation, and imposed caste." Unlike the rest of the American South (and more like northern cities), blacks in Texas lived in urban areas in segregated neighborhoods. What shocked many white people in the Lone Star state was the level of black frustration expressed on television news stories from big cities like Los Angeles, Detroit, Newark, and others. This did not echo down to Texas, which Fehrenbach said had "a generally clear understanding between both black and white communities that the Texas economic and political power structure would not tolerate civic disorder." [36]

How all this would affect the Park Service in its efforts to interpret the realities of Fort Davis became quite clear within six months of opening its doors. Superintendent Becker wrote in his monthly report for June 1963 that an "indignant lady visitor" approached one of the staff to declare: "You mean they're [the park service historians] going to make a shrine out of this nigger place!" Either this woman or someone else then voiced similar disgust at the Fort Davis Drug Store. Said Becker: "This party complained to the people that run the drug store . . . , that there were colored soldiers stationed at [Fort Davis] and this information was not included on our entrance sign, so that this particular party could by-pass this contaminated area." That same month, Becker was asked by Barry Scobee if the park service would accept a Texas state historical marker commemorating "the outstanding Confederate historical figure" for Jeff Davis County. The old judge had no more room on the courthouse lawn for this state-mandated marker because of "the great increase in historical interest generated in the last year or so." Masking his dislike for the intrusion of rebel history on federal property, Becker told regional officials that he had "registered neither strong approval nor disapproval, particularly since there doesn't seem to be much we can do about it unless we work with the State Highway Department." [37]

Park service officials tried to accommodate what they saw as a parochial vision of history by using the Fort Davis museum as a source of information that few visitors (or locals) had encountered. One technique attempted was "the feasibility and desirability of using direct quotations for much of the [label copy] text and in printing them on antique type face." Assistant SWR director George W. Miller believed that "these labels will thus become a minor design motif," and the "labels themselves will take on something of the quality of specimens." His goal was to retain as much of the story of Fort Davis as possible, even though Western Museum Laboratory specialists warned that "most visitors stubbornly resist reading." "So be it," said Miller, as he declared: "For once, let us consider the literate as well as the uninterested; this is a cheap way to do it." The assistant director planned to utilize the talents of Santa Fe-based publisher Jack Rittenhouse, former editor of the University of New Mexico Press, to print these labels in nineteenth-century cursive script, and then to work with Robert Utley and Frank Smith on completing the exhibit text in June 1963. [38]

Throughout the spring and summer of that year, Bob Utley and his associates on site and in Santa Fe worked to represent the Fort Davis story in as complete and interesting a fashion as possible. Jackson E. Price, assistant NPS director for conservation, interpretation and use, wrote to the SWR director on April 18, 1963 to praise the work of Utley, and to express Washington's appreciation for the challenges that Fort Davis posed. "Experience in other parks where historic buildings are being used as Visitors Centers," said Price, "has amply illustrated the difficulty in minimizing limitations imposed by structures originally designed for quite different purposes." To that end, Price suggested that in converting HB20 (barracks) into the Fort Davis visitors center the regional office should note that "the complete absence of AV [audio-visual] interpretive devices is conspicuous when the Fort Davis Prospectus is compared with other current ones." Price wondered if such equipment "might be helpful in presenting the general background story of the fort," and that "perhaps the possibilities of a few audio stations along the tour route have been fully considered." [39]

Turning to the historic structures and their interpretation, Price agreed with regional and park opinion that the post hospital "does not appear to outweigh in relative importance other ruined structures in the fort complex not recommended for restoration," as the "essential aspects of the story associated with the hospital could be presented by other means." The assistant NPS director for conservation was less sanguine about the museum design to "place formal exhibits in refurnished historic structures." Price considered this request to be "contrary to practices well established both within and outside the Service." Citing as his evidence the National Park Service Field Manual for Museums, Price warned that "the undesirability of attempting this in the barracks squad room, commanding officer's quarters or the hospital, if it were restored, will become apparent when furnishing plans are developed." The conservation director preferred that Utley and the museum laboratory "include these [exhibits] in the Visitor Center or provide for them in other space distinct from the refurnished quarters." Price thus paid close attention to the label copy for the museum, as he saw this location as the primary focus of interpretation for visitors to Fort Davis. This in turn led him to apologize for allocating too little money in the fiscal year 1963 budget for exhibit construction; a situation that would have to be corrected the following year. [40]

The search for the proper historic artifacts to place in these quarters occupied much of the time of Frank Smith while he served in Santa Fe as regional curator. In late April and early May 1963, Smith spent over a week traveling throughout southern New Mexico and west Texas to locate antique dealers willing to sell artifacts of nineteenth century military life for inclusion in the Fort Davis museum. In El Paso, Smith claimed to have "visited virtually every pawn shop and gun store in town." Among his acquisitions were authentic revolvers, sabers, and photographs. Smith noted in particular the artifacts housed at the museum of the Fort Davis Historical Society. Somehow the society had managed to acquire "an 1873 Springfield rifle, with bayonet, which appears to be in excellent condition, and a series of Waybills, schedules, tickets, money orders, etc., from at least two of the stagecoach lines which ran through Fort Davis." Of less value was time spent in the "Treasure Trove Antique Store" in town, where the regional curator found items that were too "high-priced," or were replicas of historical arms which were "obviously [of] French manufacture." [41]

Frank Smith's forays into Southwestern antique and pawn shops on behalf of Fort Davis proved enjoyable to the regional curator, and may have stimulated his interest in 1965 to succeed Michael Becker as superintendent. Less thrilling was the experience that fall of park historian Erwin Thompson, sent out by the superintendent to get photographs of battle sites to include in Bob Utley's museum exhibit design. On October 3, 1963, Thompson drove a park service vehicle south of Sierra Blanca to locate the route taken by Colonel Grierson that culminated in the Battle of Tinaja de las Palmas. Using a recent map printed by the U.S. Geological Survey, Thompson followed what appeared to be an unimproved dirt road open to the public. At a point several miles down the road, Thompson came upon the house of the caretaker of the surrounding ranch, a man named Jim Tom Love. Described by Thompson as large, somewhat inarticulate (he had, in Thompson's words, a "fifth-grade education"), and hostile to public officials, Love called upon the park service historian to halt and explain why he was on private property. Thompson told investigators from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and also the Hudspeth County sheriffs office, that Love "jerked him out of the car and cursed at him," then hit Thompson on the back of the neck with a pistol several times. Love then ordered him at gunpoint to come with him into town to see the sheriff. [42]

The incident in the west Texas mountains left Thompson, Becker, and other park service personnel bitter at the parochialism of justice in the area. As the foreman of the Hot Wells ranch (owned by the prominent Espy family), Love was well known to local law enforcement officials. His explanation that Thompson had trespassed on private land seemed to satisfy the justice of the peace of Hudspeth County who handled the complaint, as Texas law permitted "any means" necessary to remove someone from private property. Thompson was released when Love decided not to press charges, but the park service historian did try to bring Love to trial on charges of "unlawful restraint." The federal courts in El Paso refused to hear the case, but in December 1963 the Hudspeth County Court convicted the caretaker of "aggravated assault," and fined him $25 dollars. This outraged Superintendent Becker, who asked regional officials to protest the decision. The FBI concluded that there was not compelling federal interest in the case, since "Mr. Thompson was actually a trespasser and, although the assailant may have used more than permissible force in removing him, a $25 fine for such a violation might not be considered unconscionably small." The NPS and Justice Department further believed that Thompson's "civil suit against the assailant should adequately vindicate any wrongs he may have suffered." [43]

The Jim Tom Love incident left bitter memories for Thompson, Becker, Bob Utley, and other park service officials of the time. In a pointed memorandum to the NPS field solicitor in Amarillo, Becker wrote that "the Justice Department may consider the case closed, but neither the superintendent nor Mr. Thompson feels that justice has been served." The Hudspeth County Court ruling left the impression, said Becker, "that if one is big enough and mean enough and has $25, he could apparently assault federal officers with relative impunity." Thompson himself had to wear a neck brace for several weeks because of fractured vertebrae, and later contracted infectious hepatitis. The lawsuit went nowhere, as the Justice Department and NPS failed to support Thompson's claims. Even on the park grounds, the historian could find no escape from the notoriety of the attack. Later in October 1963, Superintendent Becker reported that a local woman approached Thompson while on duty and asked if he had been "hit by a Texas man." When Thompson replied in the affirmative, the woman declared: "You're lucky you're still alive!" This proved too much for the superintendent to ignore, and he informed his superiors sarcastically: "Makes one feel real neighborly toward his fellow Texans." [44]

Thompson's injuries and time lost forced Superintendent Becker to focus more closely in the fall and winter of 1963-1964 on the historical research program at Fort Davis. As word circulated about the presence of a new historic site, with national standards of preservation and collection of data, Fort Davis' staff received calls and letters about potential artifacts and materials, as well as requests for assistance by local historical agencies and groups. The prestigious Amon Carter Museum of Western Art in Fort Worth offered to loan the park its series of slides depicting Frederic Remington's famous scenes of buffalo soldiers. The Amon Carter also promised to send copies of Charles Schreyvogel paintings for the planned museum at the park. Such support from private individuals made the work of preparing the visitors' exhibits that much easier and less expensive, and also indicated the level of interest throughout the West in a successful interpretive program for Fort Davis. [45]

Recreating the mood and spirit of the old military frontier also meant that the staff had to take on duties normally associated with scholars or professional historians and archeologists. In January 1964, Ranger Bob Dunnagan found traces of the first Fort Davis (1854-1861) in Hospital Canyon, and began a series of excavations to determine its extent and value to the park. Erwin Thompson also returned to his research duties that winter, locating the site of the Battle of Tinaja de las Palmas, which had drawn him into the Jim Tom Love incident earlier in the fall. He also found the site of the Battle of Rattlesnake Springs in his travels through the west Texas mountain country. Making Fort Davis' expertise available to local historical groups also seemed wise to Michael Becker, as he responded favorably to the request from the Marathon Historical Society for help in "platting the Fort Pena [Colorado] subpost" southeast of Alpine. [46]

The most dramatic effort at recapturing the past at Fort Davis came in the fall of 1963, when regional museum curator Frank Smith promoted his idea of reenactments of the troops on parade, and the use of recorded music to evoke the sense of daily life at the post. Smith remembered in 1994 how the museum system of the Southwest Region "was in turmoil," and how it "had not been updated since the 1930s." The MISSION 66 program promoted the establishment of museums to attract and inform visitors, and the region witnessed the creation of nearly two dozen such facilities. Fort Davis offered Smith and the SWR the best chance to experiment with advanced technology and research methods of historical interpretation, and the future superintendent worked closely with Michael Becker, Robert Utley, and WASO historian Harold Peterson to create just the right setting for the retreat parade and music. [47]

What made the research of the retreat so authentic was Smith's use of a special cavalry unit stationed at Fort Sill in western Oklahoma. Major General L.S. Griffin, commander of Fort Sill, told SWR's Daniel Beard in October 1963 that his post had a private unit that had formed to participate in Armed Forces Day celebrations. This group, consisting of some 50 mounts and riders, could perform for the park service if the NPS provided the musical arrangements. To that end, Donald J. Erskine, NPS chief of the audiovisual services branch, wrote to Dr. William Fulton, professor of education at the University of Oklahoma, to identify someone capable of recording the sounds of the parade unit. SWR director Beard wanted only the highest quality of production for the parade retreat, given the attention and funding already expended on Fort Davis. After listing for the NPS director all the specifications for the performance of the Fort Sill unit, he reminded his superior that "this may prove to be a long-lasting and wide-spread program. In any case, we do not want to settle for anything which could become, in future years, simply 'run of the mill' or mediocre." Thus the park service spared no expense to use the Motion Picture Department of the University of Oklahoma, and to generate sound in excess of 20,000 decibels to blanket the parade ground as the Army would have done. [48]

As the restoration of post life moved forward in late 1963, so did the plan for exhibits in the park museum. The Western Museum Laboratory released in November its comments on the work of Messrs. Utley, et al, asking Superintendent Becker to add his thoughts prior to final acceptance of the plan. John W. Jenkins, WML chief, had mostly grammatical corrections, and saw little difficulty with the historical content of the plan. Michael Becker echoed Jenkins' sentiments in January 1964, praising the hard work of the design and research team: "There is excellence all the way through." The report revealed the lengths to which the team went to ensure historical accuracy, and the imaginative strategies that they employed to bring out the Fort Davis story for visitors. Between the exhibits, music, parade retreat, and historic structures, Fort Davis seemed ready in the spring of 1964 to fulfill the hopes of the park service to become what all involved considered the best statement of frontier military life in the Southwest. [49]

With all this attention paid to the cause of history at Fort Davis, Michael Becker had high hopes in the winter and spring of 1964 as he sought to fill the position of temporary historian. Erwin Thompson needed help meeting the deadlines emerging from the dual track of historic structure completion and museum exhibit design. Unfortunately no one accepted the position as advertised, and by April the superintendent changed the scope of work to permit the hiring of a college student. Becker called Barry Scobee's old friend at the Texas Tech library, Frank Temple, and asked his help in locating someone who could work for the summer as a seasonal employee. Responding to the call was Jerry Rogers, then in the spring of 1964 a graduate assistant pursuing a master's degree in history at Texas Tech. On May 31, Rogers, his wife Peggy, and their infant daughter arrived in Fort Davis to begin a career that would lead the young history major to Washington as associate director for cultural resources for the Park Service, and in 1995 to Santa Fe to become the last director of the Southwest region. [50]

Rogers' presence on the Fort Davis staff allowed for an acceleration of historical research and writing of reports for the museum and historic building programs. On June 30, the Fort Davis Historical Society closed their small museum on the grounds of the park, and Becker, Thompson, and Frank Smith looked over the artifacts for potential acquisition. Jerry Rogers went to work immediately writing research reports on the historic structures, leading Becker to tell the regional office: "[Rogers] is to be complimented on [the reports'] high quality and for his ability in the field of historical methodology." In July, Becker further praised the Texas Tech graduate: "Ranger Rogers . . . prepared a very fine brief on the results that might be anticipated when HB28 (Post Chapel) and HB40 (Quartermaster Corral) are reconstructed." Rogers was "now well underway in research on HB46 (Post Hospital) in preparation for a Historic Structures Part II Report." All this work highlighted the park's need to send Erwin Thompson to Washington to seek out National Archives material that Robert Utley had not identified in his earlier studies, which had focused more on the military campaigns of the soldiers rather than on their daily life and surroundings. [51]

Turning his attention in the fail of 1964 to the interiors of the historic structures, Michael Becker addressed two concerns of the museum design team: the artwork for the visitors center, and the furnishing plans for the officers' quarters. Park service officials in Washington and San Francisco's WML suggested that Becker employ Nick Eggenhofer of Cody, Wyoming, to paint the murals in the museum. NPS historian Roy E. Appleman wanted the Wyoming western artist to consider as many as seven scenes, all featuring soldiers in the field engaged in combat with Indians. Becker concurred, but worried about the cost (Appleman suggested paying Eggenhofer $5,000 for three paintings). "A mural in the Fort Davis visitor center," said the superintendent, "would put this museum on a par with some of the better ones in the System." What concerned Becker was his realization that "there is a lot of research that must be done if the furnishings plan is to be a proper one, and that research is going to cost money." Purchases of artifacts for the historic structures "are undoubtedly going to cost much more than the original estimates," Becker told the SWR director, and plans for "saving the hospital and HB-18 are going to be expensive propositions." For those reasons, the superintendent asked for only one mural in the visitors center, "located on the east wall in that area between the window and the porch." Becker saw the reasoning behind Appleman's plan, but believed that "a little lobby furniture, while not as aesthetically desirable, would in many, many cases fill the need of the visiting public more than that of the art work." [52]

The superintendent's caution about the scale of research and acquisition of furnishings echoed concerns within the park service. In June 1964, the regional office asked the architects of WODC for advice on Fort Davis. Jerry Riddell told the SWR director that "we would recommend that considerable effort should be made to find a private donor to provide the enthusiasm, money, etc., for the work." This reflected the rising cost of Fort Davis rehabilitation, and also the WODC's experience with a similar refurnishing study done for Fort Laramie National Historic Site by Nan Carson. "We would hesitate to evaluate, cost wise, Miss Carson's report on the Post Surgeon's quarters at Fort Laramie," said Riddell. She had written a 120-page study that lacked "pictures of historical furnishings, typical interiors, elevations drawings of the furnishings or cost estimates of the individual items." Fort Davis was not comparable to the site at Fort Laramie, and the WODC chief architect suggested that SWR seek out someone else for the task. "We would hesitate to recommend a female interior decorator for the furnishing of the barracks," Riddell concluded, and suggested instead "someone who has done a hitch without commissioned background, and he might well be colored [a black person] to give further authenticity to the job." [53]

The Southwest region disregarded Riddell's opposition to Nan Carson's work, or her perceived inability to recreate a man's world in the barracks at Fort Davis. In September 1964, Becker learned that Carson would prepare a furnishing study for his park sometime during the following 12 months. This came on the heels of a request from Jane E. Negbaur, assistant home furnishings editor of Family Circle Magazine, who asked if she could send a photographer to the post to study the historic character of homes in west Texas. Becker promoted the work at his park as the type of setting that Negbaur envisioned. Unfortunately, said the superintendent, "it will be several years before the very handsome stone quarters of the commanding officer will be fully restored and furnished as it was in the 1880s." Becker, who had yet to learn of the selection of Nan Carson to conduct such a study at Fort Davis, nonetheless told the Family Circle editor: "We feel sure this structure and its furnishings will be well worth a feature article when finished - about 1967." [54]

Compounding Becker's problems in accommodating Nan Carson's work was the lack of detail on the interiors of the buildings, and Erwin Thompson's departure in September for a two-month training program at the NPS' Mather Training Center. The superintendent also noted that "all restoration at Fort Davis is being done in terms of the '80s [1880s] due to peculiar conditions in building alterations and construction during that decade," and because "there were nine significant occupants of the CO's [Commanding Officer's] house during that period and we do not yet know which one(s) have left the best records for that purpose." Historical research to date indicated that "the promising colonel was Benjamin Grierson." Among the reasons cited by Becker were: "His tenure was the longest [1882-1885]; he was one of the more positive characters in the position; and he had later ties in the Fort Davis community as a retired general." Becker believed that his staff could compile the necessary documents for Nan Carson by June 1965, and that the regional office would know best how much time and money her efforts would require . [55]

The historical work accomplished at Fort Davis in its first two years animated Michael Becker's first "annual interpretive report," delivered to the NPS director on January 12, 1965. The superintendent remarked upon the strong visitation that his park had witnessed: 86,565 since opening 24 months earlier. Many were drawn by the novelty of a park under construction; others by the distinctive story unfolding before their eyes. Due to the curiosity of the visitors, Becker lamented that "only slight progress was made in the preparation and installation of interpretive markers concerning the history of the fort." Vandals also found the signs attractive, requiring more permanent anchoring and higher cost for replacement. Ranger Bob Dunnagan had built a series of redwood nature trail signs in the shape of an NPS arrowhead which visitors found "quite pleasing." With the closing of the Fort Davis Historical Society museum, all these indicators of park information became even more critical. [56]

Superintendent Becker then spoke of the need for more historical research, both documentary and artifactual. Word had reached the park that Robert Utley's historical handbook neared distribution, and the park staff received many visitor requests for such a publication. Then the increased efforts at research and excavation undertaken by Messrs. Thompson, Dunnagan, Rogers, and local schoolteacher John Mitchell unearthed over 15,000 artifacts. "We are greatly behind in the cataloguing of these specimens," said the superintendent, and he saw the need for a full-time curator to reduce not only this backlog but the new acquisitions from future excavations and private donations. One example of the latter that Becker wished to draw to the attention of NPS officials was "five color slides of water colors showing the first Fort Davis, painted by Capt. Arthur T. Lee in the 1850s," sent to the park by the Rochester Museum of Arts and Sciences in upstate New York. Becker could also report that the Newberry Library in Chicago had agreed to send 2,400 pages of microfilm from its Grierson papers collection; a source of great value to Nan Carson when she would arrive to design the furnishings of the historic structures. Finally, the superintendent calculated the success of the historical work at his park by noting a visit in November 1964 by some 30 national travel writers as part of the "Texas Travel Writers Tour." Becker complained that "the visit was much too short for anything but a fleeting contact," and reported that "there seems to be a widespread illusion that the length of a visit must be measured against the number of acres in a park." [57]