|

Fort Davis

A Special Place, A Sacred Trust: Preserving the Fort Davis Story |

|

Chapter Five:

Encounters with the Ghosts of Old Fort Davis: Interpretation and Resource Management, 1966-1980

As Superintendent Frank Smith and his staff folded the chairs and took down the bunting from the highly successful dedication ceremonies of Fort Davis, they could take pride in the swift work of restoration at the "best preserved frontier military post" in the National Park Service. The record throng gathered on the old parade ground had been given a glimpse not only of the wonders of the past restored, but also of what the park service could accomplish when the nation's leaders provided it with sufficient resources and guidance. The next 15 years, by comparison, would witness in the Davis Mountains the challenge that the NPS faced in bringing its standards and strategies to bear upon a facility that would not attract such notoriety again, nor would it be graced with the presence of such dignitaries as the First Lady, Secretary of the Interior, and the governor of the state of Texas. Finally, the decline of fiscal support in the late 1960s and early 1970s would make Fort Davis yearn for the heady days of generous budgets, and would influence matters of administration, resource management, historic structure interpretation, and visitor services.

Where the NPS and Fort Davis promoters benefitted from the nascent liberalization of American politics in the first half of the 1960s, forces at home and abroad in the latter half of the decade shifted the nation toward more conservative and combative postures in matters of public service and financing of national parks. The escalation of the conflict in Vietnam required more monies to be diverted from domestic concerns, even as the rising casualties in Southeast Asia made many citizens suspicious of the federal government's role in public affairs. Added to this was the downturn in race relations, despite federal regulations requiring more access to employment of women and minorities. Riots in major American cities over issues of fairness and equity did not touch far west Texas, but the heritage of Fort Davis (a black post in a white ranching community with awkward relations between Anglos and Hispanics) brought home the question of balance and accuracy that would shape interpretive programs at the historic site once the "easy" work of building restoration concluded.

Fort Davis would be led by two superintendents of differing character and training in the years 1966-1980: Frank Smith, who would remain after the dedication for another five years, and Derek O. Hambly, who managed the facility from 1971-1978. The former was interested in the evocative power of the park, and worked most on its museum and retreat parade (especially its music). The latter, a naturalist and biologist by training, would be remembered by staff for his desire to delegate to his employees the course of park interpretation, and for his efforts to round out the park's boundaries and find its identity as an historic site. In neither case, however, did the Park Service place an historian in charge to guide the unit as it searched for the right combination of data and interpretation that would satisfy the varied constituency of Fort Davis: the national perspective of the NPS, the local concerns of the community, and the growing awareness by scholars of the role of race and ethnicity in public affairs and private life.

The historian Michael Kammen spoke to the problems that Fort Davis and its parent agency would have in moving through the thicket of public opinion and scholarly debate as a repository of the nation's frontier past. "The differences . . . between the roles of tradition and memory," said Kammen, "have less to do with what is remembered, or how traditions are transmitted, and more to do with the politics of culture, with the American quest for consensus and stability, and with the broad acceptance of the notion that government's role as a custodian of memory ought to be comparatively modest." That had not been the case in the first five years of Fort Davis' existence as a national park, but would loom large as superintendents Smith and Hambly juggled NPS directives, regional sentiments, and congressional constraints on development of a park that had enchanted so many park service professionals in its formative stages. [1]

Superintendent Smith became aware of the new realities descending upon his park within days of the departure of Lady Bird Johnson and her entourage. By May 1966, Smith had been informed of the reduction of staff at Fort Davis, just as the visitor season had begun. He informed the SWR director that his park could anticipate visitation in excess of 250,000 in the next two years, given the potential for auto travel to Texas and Mexico for the 1967 San Antonio Hemisfair and the 1968 Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City. Smith also had too many facilities to supervise for the staff allocated in 1966; a year when President Lyndon Johnson reduced non-military expenditures to subsidize over 500,000 uniformed personnel stationed in Southeast Asia. Matters only worsened as Smith developed his budgets for fiscal year 1969, realizing that he could not meet the plans of the early 1960s with the funds at hand (he had hoped to have trails ready and work done on the original fort [1854-1861]). [2]

Concern about visitation would accelerate throughout 1967 and beyond for Smith, as each month saw increases (despite the bulge created in the records by the dedication ceremonies). Fort Davis did not charge admission in these years, nor did it have an accurate method of assessing visitor totals. Smith used a multiplier of automobiles counted in the parking lot, the average of 3.5 to 3.7 persons per car, and the number of hours estimated that each visitor spent on site. Easter Sunday 1967 set a record of 2,676 visitors, with 4,793 people coming to the park on the four-day Easter weekend. Variables like hot weather would cause declines in a particular month, but the superintendent reported to his superiors in Santa Fe that interest and attention in his park continued to grow as more individuals became aware of its existence, or stopped en route to other NPS attractions at Big Bend or Carlsbad Caverns national parks. [3]

|

|

Figure 39. Richard Razo (on right) and

other Cooperative Education Students performing curatorial work (early

1970s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 40. Superintendent Frank Smith

giving Superior Performance Award to Pablo Bencomo (July

1968). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

The issue of hiring at Fort Davis occupied the thoughts of Frank Smith a good deal in the spring and summer of 1966, as he looked back upon the changes that were sweeping the park service that decade. In July he offered "one man's opinions" to the NPS "Field Operations Study Team" that solicited comments from the field in response to director George Hartzog's plans to reorient the park service with new definitions of employment. Smith, a veteran of 16 years of service with the NPS, noted that his agency "is operating under the tightest economic squeeze we have ever known, in relation to workload." Factors of economic growth, population increases tied to the maturing of the postwar "baby boom," and the expansion of leisure time only exacerbated the "continuing pressure between ceilings of all types and diminishing manpower relative to new programs and new facilities," which Smith predicted "is not going to ease--rather, we may expect it to get tougher." Unlike the Great Depression, Smith did not see new funds on the horizon to meet the needs of the new parks created in the frenzy of the early 1960s. Instead, he called upon the NPS to include small parks like Fort Davis in their calculations of workload and job description, disliking the natural tendency within the agency to link all pay grades and promotions to the duties assumed at the largest NPS units. Smith also asked for a reduction in the amount of report-writing and paperwork assigned to the field; a situation he considered onerous for Fort Davis, where staff were spread thin without the support of larger parks like Grand Canyon or Yellowstone. [4]

What allowed Smith and the staff at Fort Davis to overcome the lack of NPS funding for personnel was the hiring of minority and youth employees through several of the 1960s' "Great Society" work initiatives. The primary program was the Neighborhood Youth Corps (NYC), which came to the Davis Mountains-Big Bend area in the fall of 1966. Superintendent Smith wrote that September to Walter Parr, the Alpine-based director of the Big Bend Community Action Agency, encouraging him to send prospective NYC workers to Fort Davis. He considered employment at his park to be more than "routine labor." Instead the youth could engage in "the glorification of our national heritage;" a reference to the types of work needed at the park. Smith conceded that "simple maintenance" like "the brushing out of trails" would be required. Yet he could also offer them "more academic pursuits such as the cataloguing of museum specimens;" a task long delayed because of understaffing. [5]

Helping Smith in the task of selecting and training these youth was Pablo Bencomo, whom the superintendent praised for seeking out the "brightest and best" among community members to work at Fort Davis. Years later, Smith remembered that the NYC employees performed valuable services of maintenance and preservation, while also helping address "an obvious imbalance in the NPS" because the vast majority of Fort Davis NYC staff were Hispanic. The training process at the park differed from that offered to conventional NPS hires, however, with much emphasis on basic job skills. One example of the type of supervision required of NYC employees was the "counseling" mandated by the federal government. In training the youth to work with artifacts, Smith, Bencomo, and other full-time employees led them in discussions about "the growing need for education in the modern world, and the loss to society and the individual through leaving school." Chief NPS curator Harold Peterson came to Fort Davis from Washington in November 1966 to conduct workshops for the NYC staff on artifact preservation, and for the Fort Davis employees on how to handle the youth. Smith also recognized the role of race in the NYC program, telling his superiors in Santa Fe that the use of minority supervisors gave the Hispanic staff "a clear indication that there is no minority line drawn at Fort Davis nor in the Service." The superintendent recommended that NPS send minority park service employees to visit the NYC program to remind the youth "that they are not second-class citizens in the eyes of the Service, and that the Service does not recognize differences in this regard." [6]

The impact of ethnicity on Fort Davis reached beyond federally sponsored youth employment to the park service's own personnel actions. The "imbalance" to which Superintendent Smith referred had its counterpart in the ranks of seasonal and full-time park employees, even though Fort Davis had a long history of multiculturalism as well as racial tension. To that end, Smith worked throughout his tenure as superintendent to attract blacks and Indians to the park staff: the former because of the link between the buffalo soldiers and the interpretation he wished for the park; the latter because of the need to tell the story of the Native societies who had inhabited the Davis Mountains and Trans-Pecos region, forcing the United States to erect the frontier military post in the first place. Smith recalled in 1994 how difficult it had been to bring black seasonal employees to Fort Davis in the 1960s. He traveled to Dallas and Austin to speak with guidance counselors and placement officers of historically black colleges about sending young men and women to west Texas to work for him. Other parks were conducting similar recruiting ventures, as were private corporations and public agencies eager to include minorities in their workforce. The isolation of Fort Davis thus hurt Smith's chances with urban blacks, while others disliked what they saw as "tokenism:" the employment of a handful of minorities to assuage what they considered to be "liberal guilt." A final obstacle for Smith in bringing black people into the park service was the reputation that the city of Odessa received in national news media as "the most discriminatory town in the US." Even though Odessa was 160 miles away from Fort Davis, eastern and southern blacks who knew little of the geography of west Texas believed that conditions in the oil boom town were typical of the entire region. [7]

In the spring of 1967, Superintendent Smith thought that he had attracted a local college student, Ray Nelson, to come to work that summer from nearby Sul Ross College. Nelson, who played football for the Alpine school, received instead an offer from the Dallas Cowboys professional football team to join their preseason training camp, and thus Smith lost his best chance at a black seasonal who could represent the story of the soldiers who had inhabited the post after the Civil War. Smith, however, had more success recruiting an Indian employee, Frank Chappabitty, a Comanche from Lawton, Oklahoma, who attended the University of Oklahoma in Norman. Smith had also employed Fred Peso, a senior at New Mexico State University who was a member of the Mescalero Apache tribe; the people most closely linked to the history of the Trans-Pecos. The need for Indian voices in the interpretation of the Fort Davis story eventually prompted Mary Williams and Nicholas "Nick" Bleser, both historians and rangers, to apply in 1970 for the NPS' "Indian Youth Program." This would have employed four Indian youth for 30 days to acquaint them with careers in the park service, as well as to "enlighten and educate visitors with regard to modern (and possibly historic) Indians in the course of routine conversation." [8]

Despite the commitment of the NPS to hiring additional staff for the purposes of affirmative action, and Smith's desire to represent the Fort Davis story more accurately, continued reductions in operating budgets for the park service took their toll on the management of the park. In October 1968, as the Vietnam war reached traumatic levels, and the highly contentious presidential campaign moved towards closure, the park service informed Smith and his peers that there would be no new staffing for the following tourist season. Smith suggested that in order to save money for summer seasonal hires, he would close the park for two days per week that winter. This would allow the staff to handle the crush of report-writing that had accumulated during the previous summer, and also to provide visitors during the slow season with better service. In addition, Smith learned that his chief ranger, Bob Crisman, sought a transfer to a park closer to family in Carlsbad; a situation that resulted in October 1970 with Crisman leaving Fort Davis after five years of valued service. [9]

Superintendent Smith noted before his departure in 1971 how important it was to continue searching for quality ethnic hires. On March 1 of that year, he wrote a confidential memorandum to the SWR director about his impending transfer to the Chamizal National Memorial in El Paso. His departure from Fort Davis provided the NPS with "one of the best possible opportunities for the assignment of a black American as superintendent in a small area." Smith considered his staff "already ethnically diverse," and operating at "a level of excellence which you will seldom find." For these reasons the "assignment of an employee who has not yet served as superintendent will create fewer problems for the employee concerned than in any other area I know." In addition, Fort Davis resided in an area that was "representative of a portion of black history which has not been given adequate exposure." Smith did warn the Santa Fe office that it would have to appoint a black career NPS employee so that "the community, before it can drop its own bafflers, must be made to realize that the old stereotypes have always been in error." The departing superintendent thought that "the community does not yet realize that it is indeed ready for a move in this direction," and by appointing someone whom the locals could trust "to a job which involves the fourth largest payroll in the county and which has a wide influence in many ways will prevent the development of an adverse reaction among the majority of the people." Smith then recommended to the regional director two individuals as his replacement: John A. Carrington, a community relations specialist at the Washington NPS office; and John Troy Lissimore, the historian at Ford's Theatre in Washington. "The bigots will exist," he concluded, but selections like these could help the park service, in Smith's words, "take immediate and affirmative action" to provide Fort Davis with leadership more reflective of its historic traditions. [10]

Frank Smith's awareness of the complexity of race relations in the Trans-Pecos region reflected also his sensitivity to the political nature of his park, and of the watchful eyes that local and state officials cast his way. Employment that constituted the "fourth-largest payroll" in Jeff Davis County, especially when so many minority youth were brought to the park, would not escape the attention of Anglo locals. Thus on more than one occasion, Smith had to respond to inquiries from politicians acting on behalf of constituents seeking employment at Fort Davis. The most difficult of these to address came from veterans of military service, who faced challenges finding work in the area without specialized training. U.S. Representative Richard White of El Paso, the successor to J.T. Rutherford, was approached in October 1967 by three veterans who claimed to have been rejected for positions at Fort Davis as "common labor." They claimed that those hired at the park were not veterans, nor did they have better training than themselves. "We have lived here always," said the unsigned letter from the three veterans to White, "excepting War Service." They were all "property owners and therefore Tax Payers." They believed that they were "not getting a small part of a square deal," and asked the El Paso Democrat: "Is it possible one might have to pay homage to obtain employment at this National Historic Site?" [11]

White's query forced Smith to outline in detail the procedures used by the NPS to employ maintenance personnel at Fort Davis, and to calculate the military service of existing employees. The Civil Service Commission had created the process of an "Applicant Supply File," from which Smith would draw names for employment. The superintendent had advertised the file in the nearby towns of Marfa and Alpine, as well as in Fort Davis, from which he "obtained a list which includes roughly twice the number of laborers we would normally hire." The civil service rules also permitted Smith to hire "employees of several seasons of superlative work," regardless of their veterans' status. "There also may be some concern locally," the superintendent told White, "about the hiring of five youngsters in the President's Back-to-School program. ' Community members thought that they were regular park service hires, not knowing of the various categories of federal employment. As for the complaint that Smith did not hire former soldiers: "Our current temporary labor crew includes three ten point veterans, seven veterans, and three non-veterans, which I think will demonstrate our good faith in this matter." "Let me assure you," Smith told White, "and your constituents, that there is no discrimination of any nature in our hiring at Fort Davis, nor will there be during my tenure as Superintendent." [12]

Not all of Frank Smith's interactions with Texas political figures were as difficult as employment issues. More amusing was the exchange between Representative White, Smith, and Barry Scobee about the decision by Smith to disregard Scobee's cherished tale of Indian Emily. Scobee had waited until after the April 1966 dedication ceremonies to resurrect his grievance with Smith's closure of the access road to Indian Emily's "grave." The "father of Fort Davis" first approached Texas state senator Dorsey Hardeman about the treatment that Indian Emily had received at the hands of Smith. Hardeman had also been contacted on the matter by Edward Clark, U.S. Ambassador to Australia and a west Texas history buff. Hardeman argued to Senator Ralph Yarborough that "the story of Indian Emily is so firmly established as a part of the heritage of this State, and particularly of the Davis Mountains area, that to preclude convenient public access to her grave would be to destroy a beautiful legend of our heritage." The state senator from San Angelo believed that "so little harm can come from maintaining this romantic legend that I seek your [Yarborough's] help in trying to persuade the Park Service to reopen and maintain the road up to this grave." [13]

By 1966, the NPS animus against Indian Emily had become part of local discontent with park service rules and regulations. Hardeman thus went beyond a request for help to suggest to Yarborough that deeper problems affected management of the site. "One of our big troubles," he told the U.S. senator, "in restoring such things as old Fort Davis is that, following such restoration, the rules and regulations prescribed by bureaucrats completely thwarts the original purpose of those who worked so hard, as did you and Slick [J.T.] Rutherford, to bring about its restoration for the benefit and enjoyment by the public." Hardeman, "like Judge Scobee," had "no quarrel with the personnel at the historic site." Yet he "sometimes doubted the wisdom of some of their acts in that they sacrifice too much for over-efficiency." He then recounted to the western history aficionado that Ambassador Clark had sent him his "research" on Indian Emily, in which he proved that "she was shot by a sentry from Shelby County in the back with a Long Tom Rifle." "In all fairness," Hardeman conceded, "I may add that some doubt has been expressed as to the authenticity of this story," but he chose not to "pursue the matter further because of my great confidence in the knowledge of Texas history possessed by our friend, the Ambassador." [14]

Yarborough's response to Hardeman's plea indicated the challenge before Frank Smith and his staff to balance local tradition with park service professionalism. "Prior to receipt of your letter the end of last week," Yarborough told the San Angelo politician, "I did not know that [Indian Emily's] grave and the tradition were being treated as they are by the Park Service." He agreed to "begin work immediately to try to have this slight to one of the state's heroines, one of the great traditions of the West, one of the legends of Fort Davis, corrected." The U.S. senator was chagrined because "this legend was bigger than Fort Davis before the Park Service cut away the grave and thereby tends to bury the legend." As to the charge that "the legend cannot be proved," Yarborough replied: "I see so much history miswritten, that I am ready to believe legend as so-called history." He argued to Hardeman that "history is what the writers make it, and in the realm of national effort or individual political effort, the winners usually write the history, or they write the version that is accepted in the textbooks." He went on to claim that Indian Emily was "a legend of noble sacrifice that saved the Fort," that "there was such a person as Indian Emily," and that "since the whites who were driving out the Apaches wrote the legend, I doubt that they wrote it favorably to the defeated and driven out race." [15]

Superintendent Smith recognized the depth of feeling held by west Texans toward Indian Emily, describing Scobee as Fort Davis' "severest friend and best critic." Smith told the SWR director that the former Justice of the Peace "has now begun to accuse us, evidently, of trying to suppress his favorite fairy tale." Scobee's persistence should not be discounted, said Smith, as "once before, Mr. Scobee was very much in a minority, but his efforts were to a large degree responsible for the creation of the Historic Site." Yet the superintendent believed that "it would be quite easy to spike Mr. Scobee's guns in this matter of access, by providing better information and access than we do at present, and making a considerable splash while so doing." The Fort Davis staff was preparing an "Interpretive Prospectus" that included "telling the Indian Emily legend, and presenting the facts which point towards the impossibility of the affair." This strategy would allow the staff to show that "the Service is not trying to ignore or restrict the spread of the legend." He considered the whole incident "a tempest in a teapot, in terms of the overall picture here or elsewhere." Yet "if some evidence of the Service's intentions can be presented," believed the superintendent, "it will save everyone, at all levels, a great deal of unnecessary correspondence--probably enough to pay for a good share of the exhibit!" [16]

It remained for Smith to assuage the doubts of the powerful Senator Yarborough with language more diplomatic than that shared between Park Service officials tired of the Indian Emily story. To Yarborough Smith acknowledged: "We are fully aware of the place in local affections held by the Indian Emily tradition, and we regret that it is no longer as convenient as in the past for visitors to reach the grave marker." He reminded the senator that "no valid historical evidence had been found to verify the legend," but rejected the claim that "closure of the access road" was "an attempt to discourage visitors from viewing the reputed gravesite." Instead the park merely implemented NPS procedure destined to "eliminate automobiles, roads, and parking areas that in our judgment would seriously mar the historic appearance and character that the restoration program is intended to create." In 1965, Smith and his staff counted no fewer than 35,000 automobiles circling the parade grounds, creating environmental, historical, and safety hazards. The superintendent suggested that the "standard walking tour of Fort Davis, three-fourths of a mile, is not longer than that in many of our historical and scenic parks," and visitors had expressed little concern about the distance as "an unwarranted imposition." If anyone asked to see the gravesite, and could not walk under their own power, Smith had arranged for a park service vehicle to transport them the additional 500 yards beyond the standard tour route. "We realize that this is not a wholly satisfactory substitute for unrestricted vehicular access," Smith concluded, but he hoped that it was "warranted by the important benefits to be derived from excluding automobiles from the historic zone." [17]

Superintendent Smith's concern about the impact of the Indian Emily story on his park was not merely governmental pettiness, despite the claims of local and national politicians. He was determined to tell the Fort Davis tale as accurately as possible because of his long connection to the museum profession; a link that he cultivated assiduously during his six-year tenure at the historic site. Charlie Steen of the Southwest Region had encouraged Smith in the 1950s to join local and national associations that focused upon museum interpretation and visitor services, as a way to advance the professionalism of the park service and keep the organization attuned to changes in the museum business. Smith thus joined the Mountains-Plains Museum Association, serving on its board of directors from 1966-1970, at which time he became association president for one year. He also edited the Texas museum newsletter, and sat for eight years on the prestigious American Association of Museum's council. This explained his work with Bob Utley to represent Fort Davis carefully in its visitors center. It also permitted Smith to advance the cause of racial understanding through the museum at Fort Davis. In a 1971 letter to Milton Perry, museum curator for the National Archives and Records Service at the Harry S Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, the Fort Davis superintendent spoke of the importance of NPS sites addressing cultural issues. "Our experience at Fort Davis," said Smith, "has clearly shown that even a modest assemblage of material on a single aspect of a minority's experience in the United States of the last century can be of significant assistance to scholars, with the limitations on collections more than balanced by the concentration in a single field." Smith also started the process of NPS consultation with the proposed frontier military museum in San Angelo, known as "Fort Concho." "Within a few years," the superintendent told Mrs. R G. Ross of San Marino, California, in 1968, "it may rival Fort Davis as one of the best of the western Military posts--thereby providing the sort of competition which will keep us all active and working towards the best possible visitor services!" [18]

Advising other museums in the Trans-Pecos area was not the most dramatic of Frank Smith's outreach efforts on behalf of the park service. In 1966 the NPS asked him to serve as "keyman" for the planned Chamizal National Memorial in southeast El Paso. President Lyndon Johnson, whose patronage had meant so much to the creation of Fort Davis, had also sought to advance the cause of international cooperation between the United States and Mexico. In 1963 he had urged the NPS to develop plans for a park that, rather than glorifying the conquest of the Southwest by the U.S. Army in 1846, would demonstrate how on a daily basis two cultures shared a common boundary, environment, and economy. Within three years the Fort Davis superintendent, as the NPS official closest to the proposed site on the Rio Grande, began attending meetings in El Paso designed to link the efforts of the federal governments of the two countries, along with the city of El Paso and its school district, to realize Johnson's dream of cultural harmony. [19]

Smith divided his time between managing the affairs of Fort Davis and commuting the 220 miles by car to the west Texas city of El Paso. His work at an historic site that had undergone substantial construction excited Smith with the possibility (one that few NPS superintendents ever had) to shape the future of a second unit of the park service. Determined also to fulfill LBJ's dream of a new order in ethnic relations along the U.S.-Mexican border, Smith spent a good deal of time acquainting himself with the distinctive ecology, economics, and cultural complexity of the larger Rio Grande basin. Among these efforts was his request to his superiors to fund a Spanish language training course for himself at the NPS' Albright Training Center at the Grand Canyon, and the use of Fort Davis' Hispanic employees at Chamizal. He would take his chief of maintenance, Pablo Bencomo, with him on occasion to El Paso, as Smith admired his skills at construction and personnel management. Eventually, Smith asked Bencomo to work full-time at Chamizal, offering him a higher pay grade at the much-better funded urban park. Bencomo, however, declined the invitation, as he planned to retire one day and live in his hometown of Fort Davis. Smith also brought to Chamizal Richard Razo, a former NYC staffer of the 1960s at Fort Davis, to serve as ranger. In addition, he linked programs of films and education between the two parks, and at times utilized Fort Davis funds for Chamizal purposes when appropriations for the latter were delayed. [20]

|

|

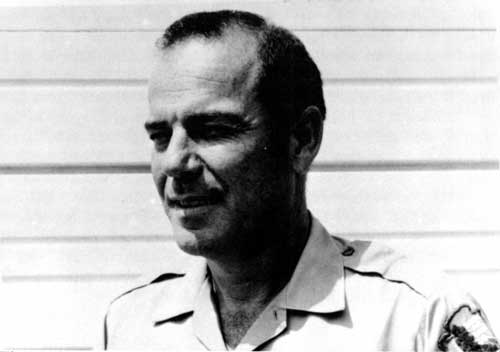

Figure 41. Superintendent Derek

Hambly. Courtesy Aggie Hambly. |

By dividing his time between Fort Davis and El Paso, Frank Smith could not devote all of his attention to either site; a situation that the Southwest Region corrected in August 1971 by transferring Derek O. Hambly from Padre Island National Seashore to the old military post. His background as a naturalist differed from Smith's work in museums and historical interpretation. For that reason Hambly deferred to his staffs expertise in history, which proved fortuitous because of the presence in the early and mid-1970s of several ranger-historians: Mary Williams, Nick Bleser, and Doug McChristian. Williams first came to Fort Davis in 1969 as a seasonal hire, with a master's degree in colonial U.S. history from the University of Connecticut. Bleser would serve as the "supervisory park ranger" until 1972, replaced by McChristian, the recipient of a history degree from Fort Hays State College in western Kansas. Bleser had developed the first "living history" program at Fort Davis, and wanted someone dedicated to this form of historical representation that had become popular in the 1960s. [21]

Superintendent Hambly faced the same issues of budget reductions, hiring practices, and community relations that had bedeviled Frank Smith in the years after the park dedication. His supervisory park ranger, Nick Bleser, set the tone for the 1970s when he wrote in January 1972 to James White of Phoenix, Arizona, who sought information about employment in the park service. Calling the situation "bleak," Bleser told White that "we have recently been ordered to cut back on approximately 500 permanent positions within the Service." This extended to promotions, which were "pretty much at a standstill." As for applicants for permanent positions, "[those] who have passed the Federal Service Examination with scores of 95 or better number in the thousands," while "we have already received more applications for summer employment during the past week than we received in several months of last year." Continued efforts by the administration of President Richard Nixon to reduce what was then considered "rampant" inflation (five percent) and federal spending led Bleser to conclude: "We have nothing here, and the whole outlook throughout the National Park System is rather grim." [22]

Because of the pressure to find employment in the face of continuing budget cuts, even the federally sponsored youth and minority programs came under close scrutiny. Alex Olivas wrote to Representative Richard White in July 1972, asking that his son Danny be hired at Fort Davis as a summer seasonal. It seemed that Danny Olivas had thought he would work at the post, only to discover that he was assigned to the nearby Davis Mountains State Park. In an interesting twist on race relations in the Trans-Pecos region, Alex Olivas charged that Hambly had hired Mexican nationals rather than his native-born son. "We hire our youths," said Bleser, "on an unbiased, combined balance of ability, interest and economic need." The youths whom Alex Olivas had challenged were American citizens of native-born Mexican parents. "We wish it were possible," Bleser wrote to White, "to hire every kid in town full-time permanently." The park informed the El Paso congressman that "we invite and welcome criticism," and believed that the Olivas inquiry demonstrated that "this must be a successful program and a good place to work if people are fighting to get in." [23]

While the youth programs appeared healthy at Fort Davis, Superintendent Hambly had fewer kind words for the change in status of rangers undertaken by the NPS in light of budget cuts. In September 1972, Hambly wrote disparagingly to the Southwest Region of the decision made in Washington to shift many positions from professional to technical status. This permitted the NPS to hire individuals with lesser educational and employment credentials, and to pay them reduced salaries. Fort Davis also could not permit the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) in 1972 to maintain a camp on the grounds. "I would not want to commit my staff to this program," Hambly informed the SWR director, "unless we have assurances that the money is available for the camp construction or improvement." Then in March 1973, the superintendent learned that the U.S. Department of Labor would no longer fund the NYC program for the park service. Hambly did note that the NYC would try to continue its recruitment of American Indian youth. While his park could use employees with such ethnicity, he realized that the heavily Hispanic population of the Fort Davis area meant that "the insertion of more manpower into the area from outside sources would not be in the best interests of the local program." [24]

While Derek Hambly could not solve the problem of declining revenues for summer employment, he did receive good news about local relations in April 1973, when Robert Utley nominated Barry Scobee for the "National Park Service Honorary Park Ranger Award." As the NPS champion of creating Fort Davis National Historic Site, Utley commended the former justice of the peace "for encouraging tourism into the region and awakening public awareness of, in particular, the national historical significance of Fort Davis." "Mr. Scobee's remarkable knowledge of history," Utley wrote, "gathered during more than a half century of research, has contributed immeasurably to our understanding of the history of both Fort Davis and Big Bend National Park." Utley, who wrote a good deal about the old frontier military post himself, further praised Scobee: "Without his knowledge and assistance--and his eagerness to answer any call for advice or information--our grasp of the region's history would be much weaker." Scobee's "contributions to the Service, to the people of the United States, and to the cause of historic preservation," said the NPS director of the Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, meant that the longtime historian of the Davis mountains would be recognized by the agency that had benefitted from his 40 years of advocacy. [25]

Robert Utley's nomination of Judge Scobee found a receptive ear in Washington, where the NPS agreed to honor the "father" of Fort Davis with its honorary ranger award. Scobee, whose relationship with Bob Utley had been strained by the latter's skepticism over the Indian Emily legend, nonetheless thanked the former SWR regional historian for his "fine, tiptop, superb, and superexcellent recommendation for me." The judge considered it "an honor indeed, and a flower in my lapel for my many remaining years--I'm only 88." Scobee, who had since moved to a nursing home in Kerrville, Texas, could take pride in the high-level NPS recognition of his efforts. "Your labor of a long lifetime," said Utley in a letter to Scobee, "has borne rich fruit in Fort Davis National Historic Site and it is only proper that your achievements have been acknowledged." Four years later, upon the announcement of Scobee's death (March 18, 1977) at the age of 91, Superintendent Hambly spoke for many within and outside the park service when he wrote to Frank Mentzer, public affairs officer for the Southwest Region: "The town of Fort Davis, and those staff members of Fort Davis National Historic Site that were privileged to know him, will always remember Mr. Scobee and his contributions to the historical heritage of this area and to the people of the United States of America." [26]

Where Superintendent Hambly had nothing but praise for Judge Scobee, his attitude towards the conditions of employment changed as the decade of the 1970s advanced. For his fulltime staff, Hambly complained about the lack of funds for travel, housing, and failure of the NPS to maintain cost-of-living standards. For the youth programs, however, Hambly began to echo the growing conservatism in the nation and within the NPS about continued reliance upon these "Great Society" social welfare programs. "For the last three years," Hambly wrote to the SWR director in July 1974, "I have been utilizing the subject programs that I inherited from the former administration of this area." Frank Smith's successor conceded that "we have received a significant amount of relatively cheap benefits from the [youth] program," but Hambly was "not . . . at all satisfied that the overall benefits are justifying the time and energy it takes to administer the program." [27]

What had triggered the superintendent's retreat from Smith's commitment to minority hiring was his discontent with the current group: "Youngsters that were barely fourteen years of age in some cases." Such employees were "too young to deal with the public effectively," said Hambly, and they were also "too juvenile to entrust with other chores such as cleaning and caring for artifacts." Even when assigned to the information desk, the superintendent complained, "it was necessary to have an older person with them at all times." Compounding Hambly's personnel problems was the fact that "the YOSSC program was supposed to have been primarily for those who were interested in going on to college." Over time the "financial limitations of the program" had caused Hambly to "pick them [the student hires] primarily from former NYC ranks." This created the belief in town that "we are expected to supply jobs automatically," resulting in "a lack of incentive and the attitude that the positions are a right rather than a privilege." From this, said Hambly, came "a degree of irresponsibility and idleness." The superintendent's corrective was "phasing out the [NYC] program in favor of hiring college students who we believe to be more responsible and more able to relate to the public." These he identified as students "from the local college [Sul Ross] in conjunction with the recently completed contract there." [28]

In the summer of 1974 Superintendent Hambly assessed the value of recruiting ethnic minorities in any capacity at his park. "While black history is a part of the total story at Ft. Davis," he reported to the SWR regional personnel officer, "it is only a part and not the whole ball of wax." Hambly had asked Sul Ross placement officials to "look for at least one black student to work in the cooperative education program." Whether Sul Ross had any such students, the superintendent informed his regional superiors: "I am not going out of my way to hire black students just because black troops were at the Fort for a period of time." Reflecting the national mood of discontent with the liberal demands of the preceding decade, Hambly further stated: "Neither am I going out of my way to hire chicanos or anglos or any other ethnic group." Rejecting the argumentation of his predecessor, Hambly contended that "we have enough worthy students of all denominations here to do the job we need to do." Thus he saw little value in making "a special effort to recruit just black students other than the effort we have already mentioned." [29]

As for his NPS-funded employees, Hambly spent a good portion of his tenure in the 1970s battling to resist the slide in working conditions and morale that eventually prompted the systemwide report entitled, State of the Parks-1980. Pay raises were few and far between, and housing in the Fort Davis area worsened as the Trans-Pecos region witnessed the oil boom that occurred in response to the quintupling of crude oil prices during the twin "embargoes" and "energy crises" of 1973 and 1979. The region had what was considered the finest crude oil in the nation (West Texas Intermediate Sweet Crude) that rivalled the quality of the Persian Gulf Arab nations that forced energy prices to rise exponentially. The situation for housing and other social services throughout west Texas grew more competitive with the high salaries paid to white collar and production workers alike, and in 1976 the NPS sent to the Fort Davis-Big Bend area a team of observers led by former Fort Davis superintendent Michael Becker to assess the crisis of living costs. Hambly took exception to Becker's decision to use housing prices and wages from Fort Stockton as the baseline data for his study, as he preferred nearby Marfa as more reflective of the situation in Fort Davis. The superintendent considered the difference crucial, as he would have to seek in the next budget the additional funds to match these higher costs of living; a situation that might jeopardize his requests for monies to correct other pressing problems of maintenance and operations. [30]

In matters of community relations, Superintendent Hambly's concerns about offending the Anglo majority in the region with minority hiring did him little good when charged by county commissioners with conspiring with federal officials to close the town garbage dump. For the first dozen years of its existence, the park had taken its trash to the open dump on the historic site property, where it was incinerated. In March 1973, the Southwest Region learned from the Texas Air Control Board that NPS use of such dumps at Fort Davis and Lake Meredith were not in compliance with federal and state clean-air regulations. Hambly became upset when he learned that other state agencies in the area, as well as local citizens, continued to use the dump, when the NPS had to pay the cost of transporting its refuse the sixty-five mile roundtrip to Alpine. The superintendent complained to local and state officials of this oversight, leading the Texas Air Control Board in the spring of 1975 to close the Fort Davis dump to all users. This led the county commissioners' court in July to call Hambly before them to inform him of their intent "to write a letter to my supervisor asking that I be removed as Superintendent." Hambly went before County Judge Wanda Adams with documents from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Texas Air Control Board explaining the problem. "Evidently," Hambly told the SWR director, "the Commissioner[s] are locked into the idea that I am meddling in affairs that are of no concern to me." They wanted to know "by what right I had to complain about the dump," and whether the superintendent "knew what the cost would be to relocate the dump." Hambly managed to elicit from his accusers the concession that "they had not explored that facet [funding a new dump] either and one commissioner stated that they had been aware of the problem for five years." The superintendent then "pointed out that personal attacks on me would not alleviate the problem, that there were other avenues to examine, and that such organizations as the newly formed Fort Davis Chamber of Commerce and the West Texas Council of Governments were two possible sources of ideas." [31]

As if the garbage dump issue were not enough to tax Hambly's patience, the U.S. Air Force in March 1978 sent to Fort Davis two officers from Holloman Air Force Base in southern New Mexico to "gather preliminary data in preparation for a possible impact statement concerning supersonic training flights over portions of west Texas." The Air Force itself had not extended the courtesy of informing Hambly of its intentions, as the superintendent had to learn of the potential overflight problem from members of the Fort Davis chamber of commerce and the McDonald Observatory. Thus Hambly had to write to Brigadier General William Strand of Holloman that "many of these buildings are fragile and could be affected by shock waves from sonic booms." The military had already established a pattern of such flights over the NPS' White Sands National Monument, some 300 miles northwest in the Tularosa basin of New Mexico. Hambly thus sought to avoid the difficulties that White Sands had earlier experienced with its Air Force neighbors during the height of training for the war in Vietnam. Said Hambly to Strand: "This office must do everything in its power to avoid any possibility of damage to these irreplaceable structures of national importance." The Fort Davis superintendent needed from Strand "assurance that the type of training area discussed by your officers during their visit would be far enough from Fort Davis National Historic Site so that no chance of damage from sonic shock waves would be possible." [32]

The best that the Air Force could promise Derek Hambly was to move its training area some 15.5 miles away from Fort Davis. The military in the years after Vietnam had begun to look for larger sections of land in which to prepare soldiers for war, especially with the focus upon air defense that required vast stretches of open space for the high-technology aircraft being designed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Hambly told his superiors in Santa Fe that "I know that a sonic boom can travel more than fifteen miles under the proper conditions." He had learned that "there is some indication that an excess of 150 sonic booms per day would be striking the ground," and that "there might be an overwhelming opposition to the noise that these training operations would create." Fearing "noise pollution" as well as "damaging vibration" from the training program, Hambly again asked the Southwest Region: "Since the National Park Service has had experience with sonic noise at other areas, perhaps such expertise will be able to determine if 15.5 statute miles is enough space" to protect his park from Air Force intrusion. [33]

Hambly's efforts to protect his historic resource consumed much of his time in the last years of his superintendency (1978-1979). In May 1979, Colonel Richard L. Meyer, commander of Holloman AFB, wrote to Wayne Cane, acting SWR director, to inform him of the continued planning for what the Air Force called the "Valentine Military Operations Area." Meyer's staff had prepared a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on the program, and had agreed to "address specific Air Force actions that have been taken to preclude a sonic boom impact upon the town of Fort Davis and the National Historic Site." This did little to satisfy concerned local residents, who approached Representative Richard White at the July 4 celebration at Fort Davis with calls to restrict the Air Force's reach into the Davis Mountains. White surprised his constituents by saying that "he did not think he could stop the proposal, nor was he inclined to do so," citing as his rationale to the Alpine Avalanche his belief "in the defense of America, and we must all make sacrifices." Instead White advised the Jeff Davis County contingent to "pursue a lawsuit to block the flights." He acknowledged that "the Air Force has refused to honor claims of damages to homes unless residents could document the exact time of day the booms occurred." White did promise to try to get the Air Force to move the flights, but he did not think that alternative sites over the Gulf of Mexico (a long distance from the pilots' home base in southern New Mexico) would appeal to the military. [34]

Derek Hambly would leave Fort Davis in the fall of 1979, still unable to gain from the Air Force any promises of protection. Nor was he able to resolve the conflict with Jeff Davis County about the offending garbage dump. These would be issues left to his successor, William F. Wallace, the superintendent of Capitol Reef National Monument in southeastern Utah, with whom Hambly traded positions. Wallace, who would stay at Fort Davis for less than one year, informed the Santa Fe regional office soon after arrival in west Texas that his major concerns for the future of park included "the possibility of U.S. Air Force overflights in the immediate future," while "the continuation of the routine burning of the local community garbage dump creates an air pollution and odor problem as prevailing winds saturate the entire Fort area during periods when the dump is burned." To this Wallace added the old concern of "developments/construction on private lands immediately to the South of the Fort [that] could create an adverse effect due to the close proximity of the main Fort structures." [35]

Because most of the critical questions of park planning had been addressed by the late 1960s at Fort Davis, it remained for the staff hired by the superintendents to implement ideas fashioned in the heady days of the park's creation. This suited the management styles of Frank Smith and Derek Hambly, as well as the procedures established by the NPS to rely upon qualified personnel to fulfill the mandates of the particular enabling legislation of a park unit. Thus it is instructive to analyze the three major categories of daily life at Fort Davis (facility security and maintenance, historic structure rehabilitation, and visitors services) through the efforts of the employees from 1966-1980. These included, but were not limited to, the work of Pablo Bencomo and his maintenance crew, and the historical research and program development of Benjamin Levy, Mary Williams, and Doug McChristian. The staff had to engage both the idiosyncracies of regional and community perspectives on the park, the dictates of NPS program and policy regulations, and the trends in historical scholarship that sought to realign the western story with that of the "new social" history of the 1960s and 1970s, focusing upon the role of ethnicity, gender, and environment as factors in the development of America's western frontier. How the park service in general, and Fort Davis staff in particular, met these objectives says much about the challenge of national organizations to change themselves, and to speak clearly to local constituencies more enamored of what Michael Kammen aptly referred to as the "mystic chords of memory" that history can provide.

Visitor safety at Fort Davis faced several hurdles in the early years of park management. The extensive repairs and alterations of structures left areas where unsuspecting patrons could harm themselves, and the potential for falling debris and walls was ever present. So too was the prospect of vandalism or damage to the structures after hours. To control these factors, the park required that rangers live on the premises (first in the old officers quarters, then in the new compound on the east side of the park) . Superintendent Frank Smith also did not have a chief of law enforcement, given the small staff on hand. Thus he had to rely upon the assistance of local sheriffs, and upon the distant U.S. Commissioner's courts in El Paso or Odessa (ironically, the nearby Marfa commissioner lacked jurisdiction in Jeff Davis County). When the mostly minor cases of vandalism and trespass were uncovered at the park, the staff also discovered that local courts were too busy to handle them. Smith and his employees thus had to work with law enforcement officials as best they could to bring the park under the protection of area officers and judges. [36]

Soon after his arrival at Fort Davis in the fall of 1971, Derek Hambly assessed the law enforcement policies of his new park and decided to update them in light of his experiences at a heavily visited national seashore (Padre Island) . Hambly chose to furnish his rangers with firearms while on active duty, but to restrict their use only to cases where "a fleeing felon may be shot at after he has been commanded to halt, even if such shooting results in death to him." The superintendent also impressed upon his rangers the fact that "they may become subject to serious administrative or judicial actions if they misuse their authority." Hambly believed that he and the supervisory park ranger-historian would be the only personnel involved in law enforcement, but that the inability of the local sheriff to respond quickly to an emergency would require the carrying of weapons by these two individuals. Even though "the overwhelming majority of visitors to the area," said Hambly, "are genuinely interested in the historical aspects of the area," and "problems have been almost non-existent," he noted that the park handled admissions fees for some 100,000 visitors per year. In addition, the book exhibits in the visitors generated some $7,000 for the Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. These might tempt someone to rob the park, as would the wealth of historical artifacts and the "collection of guns, many in working order, that might be attractive targets for thieves." He also reported that Fort Davis' proximity to Mexico brought illegal aliens into the vicinity, as well as narcotics traffic (primarily marijuana). To balance visitor security with the desire not to frighten patrons, Hambly decided to have his staff only wear their weapons when conditions dictated, and to require mandatory training once per year, with individual target practice undertaken every three months. [37]

In matters of building security, the superintendents worried most about the damage caused by fire. The high volume of dry brush accumulating in such an arid climate could harm not only the range and outlying structures, but also the valuable contents collected for deposit in the visitor center and museum. To that end, chief ranger Bob Crisman developed a working relationship between the park staff, the Davis Mountains State Park, and the volunteer fire department of the town of Fort Davis, to protect the natural and historic resources at the post. This included by 1969 a 100-gallon tank, 10 fire hoses, 35 portable fire extinguishers, and "a well stocked cache of hand tools for grass and brush fires." All park personnel were expected to respond to fire emergencies, and would be trained under NPS regulations. This was because the response time from local organizations could be lengthy: 30-45 minutes for the Fort Davis town volunteers, and over one hour for the McDonald Observatory fire-fighting team . One additional burden for staff in fire management was the fact that the park could not afford to hire a night watchman. Thus the three families living in the housing compound would have to be on alert for fires on site in the evening, and to bear the brunt of early firefighting should a conflagration break out. [38]

The issue of fire had a restorative as well as debilitating feature for the park service, and in 1972 the regional office asked Superintendent Hambly to develop a plan for "prescription fires" to "manipulate vegetation towards a definite objective, i.e., fuel reduction, removal of undesirable vegetation, favoring desirable vegetation cover in an area, etc." Hambly's staff conducted preliminary research into the history of fire at the site, and led the superintendent to write his superiors: "We are at a loss to understand how fire management could be incorporated into the total operation of Fort Davis." Their reasoning was that "we have no indication, historically or otherwise, that the historic or natural scene was dependent upon fire." Hambly agreed that the Historic Resources Management Plan and Historic Studies Management Plan of April 1971 had indicated the presence of intruding vegetation. Yet he did not approve of "controlled burning" to eradicate this. Prior to the creation of the park, cattle grazing brought to the area mesquite and other brush that posed fire hazards. Yet these had been removed by hand since the early 1960s, and the prohibition on grazing kept the growth from returning. The park also had areas surrounding the historic structures mowed regularly to reduce their potential for fire. Hambly concluded: "Deliberate management of undesired vegetation through fire could only be effected in a small area, and such fires would endanger certain historical structures and would leave a blackened area for a year unless there was heavy precipitation in which case growth would then be lush and little would have been accomplished." [39]

The only other source of structural damage to buildings and grounds at Fort Davis was the unlikely occurrence of flash flooding. In June 1974, the staff prepared for Superintendent Hambly an "Emergency Operation Plan" that included the response strategies for such an event. The report noted that Fort Davis still relied upon the historic diversion ditches and canals built in the late-nineteenth century to carry water around the post structures as it flowed from Hospital Canyon down to Limpia Creek. The staff hypothesized that flash flooding, while not in the recent memory of local residents, could be of substantial enough proportions to overwhelm the ditch system, resulting in severe damage to the historic site. Nothing of this nature occurred in the first three decades of the park's existence, but Fort Davis witnessed in October 1978 an indication of the power of nature in the arid West. In September of that year the park received some seven inches of rain over the course of six days, with 2.85 inches of that falling within one 24-hour period. Superintendent William Wallace reported to the Southwest Region that "the adobe walls in the historic structures without roof covers became saturated from direct rain and ground percolation." This in turn "disintegrated some previously stabilized sections of wall and/or foundations resulting in the loss of some complete wall structures and a large portion of one two-story building." Wallace thus asked the regional office to send a repair crew immediately, since "other structures were weakened to the point where additional rainfall or winds could result in loss of the entire walls or buildings." [40]

Of less concern than natural disasters, but equally important for management of the park, was resolution in the late 1960s and early 1970s of the boundaries of Fort Davis. Regional officials in July 1968 discovered that the NPS had not acquired all lands within the defined boundaries of the park, and asked Superintendent Frank Smith to determine how to gain control of some 12.64 acres still in private hands. Bob Crisman responded to the regional directive by researching the purchase records, learning that some $5,000 of the original allocation made in 1961 had not been paid to the Simmons/Jackson family. The chief ranger noted that "land prices in the area vary from $40 per acre to $1,000 per acre, depending on the size, quality, and location of the parcels involved." The acreage in question was in Hospital Canyon, which Crisman described as "rough, rocky terrain . . . with little or no development potential and little grazing value." He thus recommended that the NPS offer no more than $50 per acre, and the "top price should be under $1,000 and probably around $750.00." [41]

Crisman's research motivated the regional office to examine its options for acquisition of the Fort Davis inholding, with only $1,900 remaining from the original land-purchase fund to be applied to the parcel. The acting chief of the NPS' Office of Land and Water Rights wrote to Superintendent Smith in August 1968, stating that this sum "would not go very far in securing a survey, having the tract appraised, obtaining title evidence, and title insurance policy, as well as paying the landowner the value of the land." Washington office records also indicated that "there is approximately three acres of land within the boundaries owned by Mr. H.E. Sproul." The NPS official thus suggested to Smith that he entertain with Sproul the possibility of sale, believing that the park service could acquire the extra funds for purchase. Bobby Crisman thus met with Clifford Harriman of the NPS Lands Division in September 1968, reporting that "after two days of work with him we have successfully negotiated a donation of the 12.64 acre inholding on our west boundary. " The land had been owned not by Mr. Sproul, but by longtime rancher J.W. Espy. Because of the expenses involved, and the need for Fort Davis to control the acreage, Crisman convinced Mr. Espy that donating property that he could no longer graze with any effectiveness was in the best interests of all parties. This left only a parcel along the south boundary owned by M.H. Sproul that could be acquired by private developers, and Superintendent Hambly believed that the rancher would not jeopardize the neighboring national or state parks. [42]

Concern about the precise boundaries of Fort Davis had been sparked in part by initiatives taken in the late 1960s to focus more upon the natural and ecological resources of the park; a situation that had been somewhat neglected because of the high profile of historical research in the park's early years. Frank Smith had begun work in October 1966 to link the Tall Grass and North Ridge Nature Trails shared by the Davis Mountains State Park and Fort Davis. The state park would have a series of trailside panels that "present the botanical facts, and the principal coverage of ecology." Once hikers crossed onto NPS land, "they will find that the labels deal with the reaction of people to the plants, and with facts and sometimes philosophical comments about them." Smith had no naturalists on staff, and thus had to ask the regional office to identify and suggest language for the label copy on the trail signs. Smith also paid attention to regional directives regarding wildlife. "Wildlife viewing by visitors," Smith informed the SWR director, "is generally limited to a few insects and an occasional snake." He thus wondered if Fort Davis had anything to offer the team of regional naturalists who wanted to visit Carlsbad Caverns, Big Bend, Guadalupe Mountains, and Fort Davis as part of a larger study of Chihuahuan Desert ecology. [43]

Park Service officials concerned about the plant and animal life of the Davis Mountains did come to Fort Davis in the early- and mid-1970s to discuss plans to rid the area of pests, and to protect the aging cottonwood grove that had served so many generations of Fort Davis residents as a picnic grounds. Derek Hambly decided to build at the park a small herbarium, which by 1975 contained "253 species representing 64 families." The former Padre Island naturalist wanted his staff to discover "what connection any of [the species] might have with the historic aspects of the area." The superintendent believed that "pioneers, military units, and native Indians used plants for food, medicines, decorations or building materials." Yet his own studies indicated that "except for those areas directly concerned with Indian history," there was "little if anything said about the role [that] plants played in the settling of the country." Hambly wanted "the identification of plants that are of historical importance [to] be made a part of each Historical Resource Management Plan." He also hoped that "some attention [would] be paid to including plant uses into interpretive displays and programs of areas other than those concerned with Indian history." [44]

Ecological studies also extended to the increased usage of water at Fort Davis, especially the declining rate of recharge of the park's main water wells. After seven years of visitation and construction work Superintendent Smith had reported in September 1970 that "each year the water level seems to take longer to recover after the summer season." That particular summer the park staff "had some doubt for a few days as to whether or not the well was going to maintain a pumping rate high enough to meet the heavy visitor use." Smith had his staff study the problem, and reported to the regional office that "there seems to be a possibility that the well which provides water for the Fort Davis town system may be draining water from below us." Drawdown had reached only five feet above the pump, and "already this spring [1971] the pump has gone into a cycling pattern at least once, repeatedly drawing down the water to the point of cutoff before refilling the tank." A similar shortage the previous year had not occurred until "well into the summer months," leading the staff to conclude that "it is a harbinger of trouble this summer, when irrigation and visitor demands treble the current water needs." A deeper well would not suffice if the park could not expand the storage capacity of the existing tank (50,000 gallons), and Smith further noted that "there is little possibility of obtaining water from the city system without considerable expense." [45]

Given the centrality of water to visitor comfort and staff operations at Fort Davis, the NPS moved quickly to address Smith's concerns about the park's need for more water storage capacity. In May 1971, Donald C. Barrett, hydrologist with the NPS' Western Service Center in San Francisco, came to Fort Davis to examine the status of well-drilling. Barrett spoke with Pablo Bencomo about the history of water problems at the park, and then traveled to Alpine to discuss the matter with the contractor who had installed the original pumping equipment at Fort Davis. The NPS hydrologist undertook a series of tests, compared his findings to the records of water storage and use at the park, and concluded: "There is little doubt . . . that a steady decline in the capacity of the well has occurred due to the lowering of the regional water table." This caused the pump to switch on and off more frequently, threatening the system with electrical failure. Barrett speculated that climatic changes in the Davis Mountains area were in part to blame for the loss of water, but he still encouraged the NPS to plan for additional drilling, perhaps in the northeast corner of the park, which had been identified recently by a geologist from the University of Texas at El Paso, Dr. E.M.P. Lovejoy. The latter was conducting a survey of the geology of far west Texas for the state government, and contended that drawing water from that sector of the site would "take advantage of any recharge from the nearby river." [46]

The cost of drilling a well at Fort Davis, and the uncertainty of water quality in the immediate area, led the NPS in 1971 to approach the town of Fort Davis to initiate a contract to provide the Park Service with both water and sewer services. Superintendent Smith noted the high cost of connecting the park to the municipal water system ($3,200), which could be balanced against the low rates for water delivery (50,000 gallons per month at the rate of 45 cents per thousand gallons). Also prompting Smith's call for purchase of town water was the continued decline of the Fort Davis water table, which he described in June 1971 as "going down at a rate of 75 to 100 gallons production per day." The crisis conditions had led the superintendent to rent a gas generator to pump water from the "old church camp well, which might provide enough water to keep the fire control supply in the storage tank." Park service regulations required Fort Davis to retain a reserve for firefighting, which Smith described as "less than 36,000 gallons, or about one hour's fire fighting time at full capacity." Without additional moisture that summer, Smith feared that "the emergency is growing a little greater every day," and that the most expedient solution was to purchase water from town at once. [47]

Water conservation became more urgent as the decade of the 1970s brought to west Texas the international energy crisis, spawned by the decision of several Arab oil-producing nations to quintuple the price of petroleum in response to the victory in 1973 of the state of Israel in its war with Egypt. While the escalation of prices benefitted the "oil patch" of west Texas (even as it raised rents in the Davis Mountains), Fort Davis and the NPS had to adhere to new rules and regulations about energy consumption, whether for heating and cooling, automobile transportation, or lighting. Among the procedures established by Superintendent Hambly in the fall of 1973 were promises to limit driving to 50 miles per hour (a burden in the wide-open spaces of the West); reduction of office hours (the new schedule would be 8:00AM-4:30PM); setting the temperature of park buildings at 68 degrees during daylight hours in the winter, and 60 degrees at night; using the photocopying machine only between the hours of 9:00-9:30AM, and 4:00-4:30PM; and a request to staff that they share rides to nearby towns like Alpine and Marfa to reduce personal energy consumption. Superintendent Hambly also offered a warning to his staff if they did not adhere to these new regulations: "I will also consider the lack of compliance with this memorandum, on the part of any employee, when position reviews come across my desk during your annual rating period." Hambly considered this "not a threat but simply the fact that compliance during this crisis is as much a part of your job as any other assigned duty." [48]

As the energy "crisis" deepened in the winter of 1973-1974, the NPS conducted surveys of its parks to determine further measures to reduce consumption of fossil fuels and electricity. Associate regional director Monte Fitch asked Fort Davis about the impact of higher gasoline prices and the notorious closing of gasoline stations on Sundays on park visitation. Superintendent Hambly reported that Fort Davis had witnessed striking declines in attendance, beginning in October 1973 and continuing all winter. Total visitation for the calendar year 1973 fell some 27 percent, with the months of October (44 percent) and December (48 percent) leading the way. One reason for this condition was the fact that Fort Davis' off-season patronage came primarily from families in the region who traveled on weekends. With gasoline supplies uncertain, and prices high, people would stay home rather than attempt the 400-mile roundtrip from El Paso, or the 350-mile loop from Midland-Odessa. "The fuel shortage," wrote Hambly in February 1974 to the regional office, "has apparently had a very negative effect on the local merchants." So rapid had been the reduction in their businesses that "they have started advertising in area papers to the point that gas is available on Sundays in Fort Davis. " Unfortunately, this had little effect on weekend travel, and Hambly suggested to his superiors that his park could be closed on Sundays without much problem. "I doubt that our closing would affect the crisis one way or another," said the superintendent, but "if local business and our public image with that business is the primary concern, we should remain open since we are one of the prime attractions in the area along with the McDonald Observatory and the seventy-six mile scenic loop drive." Hambly thought it counterproductive for his park to close if the Davis Mountains State Park remained open, as its campgrounds "makes this a twenty-four hour area if the two units were considered as a single entity." [49]

The staff at Fort Davis worked with their superintendent that winter to devise some imaginative solutions to the shortfall of funds, visitors, and energy supplies. On February 15, 1974, Hambly sent to the Southwest Region the park's recommendations for energy conservation. The staff saw visitation as "the first order of business," and prepared a survey of "visitor trends for the past five years--origination of visitors, percentages, of local population, etc. ," to ascertain "how many there will be as compared to previous years." The NPS had also asked parks to identify sources of public transportation in their areas, and Fort Davis reported that the recently inaugurated passenger train service called "Amtrak" would have a stop in the Marfa area, and that it would increase its schedule from weekly arrivals and departures to daily. Hambly suggested that his park work with other tourist attractions in the Davis Mountains to establish "bus tours from the train deport that would last for up to a week and would allow visitation to Fort Davis, the McDonald Observatory, Big Bend, and possibly a trip to Chihuahua, Mexico." The NPS could also work with the "Texas Trail System" to bring visitors to the western part of the state. Then the staff examined issues that could be addressed internally, like "a reduced entry fee for anyone entering the various Parks by any way other than the family car;" opening the park later, because "many areas experience little visitation right after opening each day;" "the use of solar energy to run this area since the sun shines about 95 percent of the time;" and the issuance of "short-term livestock grazing permits" to "keep grasses and weeds mowed rather than use mowers like we do now. " Hambly realized that this last concept invited many new problems ("over-grazing, disease, lack of fencing controls in visitor use areas"), but he hoped that the regional office might have "other areas that this suggestion would better apply to." [50]

One unintended consequence of the policies of energy reduction and limited budget was the need by 1975 to eliminate historical activities and maintenance scheduling. Superintendent Hambly had to cancel plans for hiring six seasonal interpreters for the summer of 1976 in order to pay for basic upkeep of the post. This in turn required Fort Davis to eliminate several historic programs that the staff had developed as part of its "living history" agenda. Among these were the "twice per week drill demonstration of 1880's military," the "Apache Indian camp," the "Cavalry Soldier's Camp," the "post hospital talk," the "adobe manufacture demonstration," and the "post garden activities." When added to the decision to reduce operations per day by 3.5 hours, and not using one employee at the visitors center desk during the week, Fort Davis would save enough money to provide for mowing, custodial work, and painting of the porches and trim of the historic buildings. [51]

These activities were the heart and soul of efforts in the 1970s to maximize the potential of the historic building rehabilitation from the previous decade, as well as the continuation of research into the details of nineteenth-century daily life at the post. The 15 years prior to 1980 witnessed several initiatives that linked structural preservation with historical study of the old frontier fort, and then the attempt to dramatize that for visitors in a concept called "living history." Yet the persistent forces of park service regulation, local sentiments about the life of Fort Davis, and the churning of social and political life nationwide that affected all other aspects of park management would alter the central feature of Fort Davis: its shift in the 1970s from a construction site to a laboratory of the western military past.