|

Fort Donelson National Battlefield Kentucky-Tennessee |

|

NPS photo | |

From Henry to Donelson

Bells rang jubilantly throughout the North at the news, but they were silent in Dixie. The cause: the fall of Fort Donelson in February 1862. It was the North's first major victory of the Civil War, opening the way into the very heartland of the Confederacy. Just a month before, the Confederates had seemed invincible. A stalemate had existed since the Southern victories at First Manassas and Wilson's Creek in the summer of 1861. Attempts to break the Confederate western defense line, which extended from southwest Missouri and the Indian Territory to the Appalachian Mountains, had achieved little success. A reconnaissance in January convinced the Union command that the most vulnerable places in that line were Forts Henry and Donelson, earthen works guarding the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

Fort Henry stood on land ill-suited for forts. It was surrounded by higher ground and subject to flooding. The Confederates had begun a supporting work, Fort Heiman, on the bluffs across the river, but it was not finished. A joint army/navy operation against Fort Henry had been agreed to by Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote and an obscure brigadier general named Ulysses S. Grant. The attack was to take place in early February, using the Tennessee River for transport and supply. It would be the first test of Foote's ironclad gunboats. On February 4, 1862, Grant began transporting his army south from Paducah, Ky. He established a camp north of Fort Henry and spent two days preparing for the attack.

On February 6, while Grant's soldiers marched overland from their camp downstream, Foote's gunboats slowly approached Fort Henry. These included newly constructed ironclads Cincinnati, Carondelet, and St. Louis, as well as the converted ironclad Essex. They opened a hot fire that quickly convinced Lloyd Tilghman, the Confederate commander, that he could not hold out for long. The plan called for the gunboats to engage the fort until the army could surround it. The bombardment raged for over an hour, with the ironclads taking heavy blows and suffering many casualties. Most of the casualties came after a Confederate shell ruptured the boiler aboard Essex, scalding its commander and killing many of its crew.

The poorly located fort, however, was no match for the gunboats. To Grant's chagrin, the Confederates evacuated Fort Heiman and the ironclads pounded Fort Henry into submission before his soldiers, plodding over muddy roads, could reach the vicinity. Less than a hundred of the Confederate garrison surrendered, including Tilghman; the rest, almost 2,500 men, escaped to Fort Donelson, Grant's next objective, a dozen miles away on the Cumberland River.

At Donelson the Confederates had a much stronger position. Two river batteries, mounting 12 heavy guns, effectively controlled the Cumberland. An outer defense line, built largely by reinforcements sent in after Fort Henry fell, stretched along high ground from Hickman Creek to the little town of Dover. Within the fort Confederate infantry and artillerymen huddled in the cabins against the winter. Aside from a measles epidemic, they lived "quite comfortably," cooking their own meals, fighting snowball battles, working on the fortifications, drilling, and talking about home—until the grim reality of war descended on them.

It took Grant longer than expected to start his men toward Donelson. Several days passed before Fort Henry was secure and his troops ready to march. They finally got underway on February 11. By then the weather had turned unseasonably warm. Lacking discipline and leadership and believing that the temperature was typical of the South in February, many of the soldiers cast aside their heavy winter gear—an act they soon regretted. The Confederates were so busy strengthening their position that they allowed Grant's army to march unchecked from Fort Henry to Fort Donelson. By February 13 some 15,000 Union troops nearly encircled the outerworks of Fort Donelson. Sporadic clashes broke out that day without either side gaining ground. Nightfall brought bitter weather—lashing sleet and snow that caused great suffering.

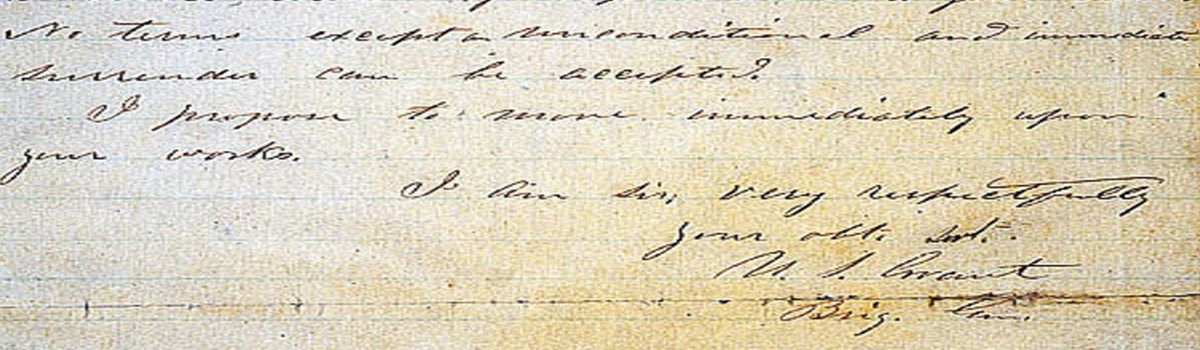

"No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted."

—Ulysses S. Grant, February 16, 1862

The Battle of Fort Donelson

February 14 dawned cold and quiet. Early in the afternoon a furious roar broke the stillness, and the earth began to shake. Foote's gunboat fleet, consisting of the ironclads St. Louis, Pittsburg, Louisville, and Carondelet, and the timberclads Conestoga and Tyler, had arrived from Fort Henry via the Tennessee and Ohio rivers and were exchanging "iron valentines" with the 12 big guns in the Confederate river batteries. During this 90-minute duel, the Confederates wounded Foote and inflicted such extensive damage upon the gunboats that they were forced to retreat. The hills and hollows echoed with cheers from the Southern soldiers.

The Confederate generals—John Floyd, Gideon Pillow, and Simon Buckner—also rejoiced; but sober reflection revealed another danger. Grant was receiving reinforcements daily and had extended his right flank almost to Lick Creek beyond Dover to complete the encirclement of the Southerners. If the Confederates did not move quickly, they would be starved into submission. Accordingly, hoping to clear a route to Nashville and safety, they massed their troops against the Union right and began a breakout attempt on February 15. The battle raged all morning, the Union army grudgingly retreating step by step. Just as it seemed the way was clear, the Southern troops were ordered to return to their entrenchments—a result of confusion and indecision among the Confederate commanders. Grant immediately launched a vigorous counterattack, retaking most of the lost ground and gaining new positions as well. The way of escape was closed once more.

Floyd and Pillow turned over command of Fort Donelson to Buckner and slipped away to Nashville with about 2,000 men. Others followed cavalryman Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest across swollen Lick Creek. That morning, February 16, Buckner asked Grant for terms of surrender. Grant's answer was short and direct: "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted." Buckner, who considered Grant's demand "ungenerous and unchivalrous," surrendered.

Soon after the surrender, civilians and relief agencies rushed to assist the Union army. The U.S. Sanitary Commission was one of the first to provide food, medical supplies, and hospital ships to transport the wounded. Many civilians came in search of loved ones or to offer support. Although not officially recognized as nurses, women like Mary Ann Bickerdyke cared for and comforted sick and wounded soldiers.

With the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson, the North had not only won its first great victory but gained a new hero—Ulysses "Unconditional Surrender" Grant, who was promoted to major general. Subsequent victories at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga would lead to his appointment as lieutenant general and commander of all Union armies. And Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox would help put Grant in the White House.

After the fall of Fort Donelson, the South was forced to give up southern Kentucky and much of Middle and West Tennessee. The Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, and railroads in the area, became vital Federal supply lines. Nashville, a major rail hub and previously one of the most important Confederate arms manufacturing centers, was developed into a huge supply depot for the western Union armies. The heartland of the Confederacy was open, and Federal forces would press on until the Union became a fact once again.

Fort Donelson Today

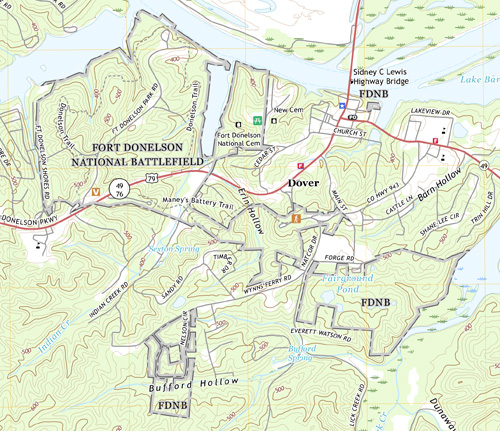

A Guide to the Park

Confederate Monument Confederate soldiers were hastily buried on the battlefield after the surrender. The exact location of their graves is unknown. This monument commemorates the Southern soldiers who fought and died at Fort Donelson. The United Daughters of the Confederacy erected the monument in 1933.

Fort Donelson Confederate soldiers and slaves built this 15-acre earthen fort over a period of seven months, using axes and shovels to make a wall of logs and earth 10 feet high. While a more permanent fort of brick or stone would have been more desirable, earthen walls were much quicker to build. Properly constructed earthworks can provide better protection than brick or stone. The fort's purpose was to protect the Cumberland River batteries from land attack. At the time of the battle, all trees within 200 yards of the fort were felled, clearing fields of fire and observation. Tree branches were sharpened and laid around the outside of the fort to form obstacles called abatis.

Log Huts Soldiers and slaves built over 400 log huts as winter quarters for the soldiers garrisoning and working on the fort. In addition to government rations of flour, fresh and cured meat, sugar, and coffee, every boat brought boxes from home filled with all kinds of things a farm or store could provide. Off-duty soldiers from the local area hunted and fished in the same locations they had frequented just months before as civilians. Sometime after the surrender, Federals burned the cabins because of a measles outbreak.

River Batteries The rivers were vital arteries that flowed directly through the Confederate heartland. Transportation and supply routes depended heavily on these waterways. Both the upper and lower river batteries were armed with heavy seacoast artillery to defend the Cumberland River, the water approach to major supply bases in Clarksville and Nashville, Tenn. It was here that untested Confederate gunners defeated Flag Officer Andrew Foote's flotilla of ironclad and timberclad gunboats.

Using the same tactics that succeeded at Fort Henry, Foote brought his gunboats very close, hoping to shell the batteries into submission. Instead the slow-moving vessels became excellent targets for the Confederate guns, which seriously damaged the gunboats and wounded many sailors. Foote, who was among the wounded, later told a newspaper reporter that he had taken part in numerous engagements with forts and ships "but never was under so severe a fire before." The roar of this land-naval battle was heard 35 miles away.

Smith's Attack On February 15 Grant correctly concluded that for the Confederates to hit so hard on the right, they must have weakened their line somewhere else. Seizing the initiative, he told General Smith to "take Fort Donelson." Smith had his troops remove the firing caps from their guns (so the men would not be tempted to stop and fire, risking greater casualties) and fix bayonets. With the Second Iowa Infantry spearheading the attack, Smith led the assault against the Confederate lines on this ridge. Smith's division captured and controlled the earthworks here during the night. Before the attack could be renewed the next morning, Grant and Buckner were already discussing terms for surrender.

Union Camp This area became a Union camp following Smith's successful attack. During the night, while both sides strengthened their positions, surrender discussions began. White flags raised over Confederate positions at daybreak on February 16 saddened the Confederates and created joy among the Federals. After the surrender, the Union troops camped here were honored by being the first to march into Fort Donelson.

Graves' Battery Placed here to guard the Indian Creek Valley, this six-gun battery saw more action when it was moved to support the Confederate breakout attempt near the Forge Road.

French's Battery In conjunction with Maney's Battery to the west, this four-gun battery was intended to prevent Union forces from attacking down Erin Hollow and penetrating the Fort Donelson perimeter.

Forge Road At daybreak on February 15, Pillow and Johnson's division, along with Col. Nathan B. Forrest's cavalry, attacked Gen. John A. McClernand's troops on the Union right flank in an attempt to secure an escape route. The attack succeeded in briefly opening the Forge Road as an avenue of escape but, due to indecision and confusion among their commanders, the Confederate troops were ordered to return to their entrenchments. Union soldiers reoccupied the area the southerners had fought so hard to control.

Dover Hotel Built between 1851 and 1853, this building accommodated riverboat travelers before and after the Civil War. During the battle General Buckner and his staff used it as their headquarters. It later served as a Union hospital. After Buckner accepted Grant's surrender terms, the two generals met here to work out the details. Lew Wallace, the first Union general to reach the hotel following the surrender, did not want his men to gloat over the Confederate situation. He instructed Capt. Frederick Knefler, one of his officers, to tell the brigade commanders to "take possession of persons and property . . . [but] not a word of taunt—no cheering."

An estimated 13,000 Confederate soldiers were loaded onto transports to begin their journey to Northern prisoner-of-war camps. Neither the Union nor Confederate governments was prepared to care for large influxes of prisoners. The Fort Donelson prisoners were incarcerated in hastily converted and ill-prepared sites in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and as far away as Boston, Mass. Fort Donelson POWs suffered more from the northern climate than any other hardship. In September 1862 most of the Fort Donelson prisoners were exchanged.

On two occasions, once in mid-1862 and again in February 1863, Confederate forces tried to drive the Federal troops from the area. Both attempts failed; but the second, led by soldiers commanded by Gens. Joseph Wheeler and Nathan Bedford Forrest, cost the town its future. That skirmish, known as the Battle of Dover, resulted in the destruction of all but four of the town's buildings. One of those to survive was the Dover Hotel, which remained in business until the 1930s. It has been restored through the efforts of the Fort Donelson House Historical Association and the National Park Service. The exterior looks much the same as it did in 1862.

National Cemetery In 1863, after the Battle of Dover, the Union garrison rebuilt its fortifications. Diary accounts by soldiers of the 83rd Illinois Regiment, stationed here after the Battle of Fort Donelson, indicate how demanding soldiering could be. Besides working on the new fortifications, the garrison protected the Union supply line. Soldiers often commented on the constant threat of attacks by guerrilla parties. Sgt. Maj. Thomas J. Baugh wrote in 1863 that the "rebels [had] been trying to blockade the river" again. Pvt. Mitchel Thompson, who was often detailed to repair telegraph lines, described the area as being filled with "rebel bands of thieves and robbers."

(click for larger maps) |

Many enslaved workers from nearby plantations came into the Union lines for shelter, food, and protection after the 1862 victory. How to deal with these refugees, still considered property by the slave owners and individual state laws, presented a problem for both the Union army and the Lincoln administration. In 1862 Grant chose to protect the slaves and put them to work for the army.

Eventually freedmen camps were set up across Tennessee, and an estimated 300 slaves wintered at Fort Donelson in 1864. The army employed men as laborers and teamsters. Women commonly served as cooks and laundresses. In 1863 the Union army also began recruiting free blacks from Tennessee and Kentucky.

Soon after the war, this site was selected for the Fort Donelson National Cemetery, and the remains of 670 Union soldiers were reinterred here. These soldiers had been buried on the battlefield, in local cemeteries, in hospital cemeteries, and in nearby towns. The large number of unknown soldiers—512—can be attributed to haste in cleaning up the battlefield and to the fact that Civil War soldiers did not carry government-issued identification. Today the national cemetery contains both Civil War veterans and veterans who have served the United States since that time. Many spouses and dependent children are also buried here.

About Your Visit

Fort Donelson is one mile west of Dover, Tenn., and three miles east of Land Between the Lakes on U.S. 79. The visitor center is open from 8 am to 4:30 pm daily. It is closed Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1. Park tour roads are closed seasonally, sunset to sunrise. See park website for current information and closures.

Trails Fort Donelson has two principal trails: the three-mile River Circle Trail and the four-mile Donelson Trail. Both trails begin and end at the visitor center. Guides to natural and historical features along the trails are available.

Please remain on the trails. Be alert for poison ivy, poisonous snakes, ticks, stinging insects, and spider webs. Do not disturb or remove any vegetation. Be prepared for strenuous walking in some areas. Service animals are welcome.

Regulations Build fires only in the picnic area (grills only). Pets must always be physically restrained and are not allowed in buildings. Obey traffic signs. Hunting is prohibited. For firearms laws and policies see the park website. Picnic in designated areas only. Relic hunting and/or use of metal detectors is prohibited. And please don't walk on earthworks.

For Your Safety Hikers using park roads should walk facing traffic and bikers should ride in the direction of traffic in single file. Drivers should observe speed limits and park only in pull-offs. Keep close watch over your children. Use caution when near the river and on trail bridges, which can be slippery. Do not walk or stand on rock walls, cannon, or earthen mounds. Be alert to uneven ground surfaces.

Source: NPS Brochure (2014)

|

Establishment

Fort Donelson National Battlefield — August 16, 1985 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History of Fort Donelson National Military Park, Tennessee (Van L. Riggins, 1958)

Accessibility Assessment Findings and Recommendations, Fort Donelson National Battlefield (National Center on Accessibility Eppley Institute for Parks and Public Lands, April 2022)

Acoustic Monitoring Report, Fort Donelson National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/NSNS/NRTR-2014/919 (Misty D. Nelson, October 2014)

Administrative History, Fort Donelson National Military Park, Dover, Tennessee (Gloria Peterson, June 30, 1968)

An Educator's Guide to Fort Donaldson National Battlefield (undated)

Archeological Excavations in the Water Batteries at Fort Donelson National Military Park, Tennessee (Lee H. Hanson, Jr., December 1968)

Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Fort Donelson National Battlefield Final Report (Dayna Bowker Lee, Donna Greer and Aubra L. Lee, September 2013)

Fort Donelson (George Henry Hicks, 1896)

Forts Henry, Heiman, and Donelson: The African American Experience (Susan Hawkins, 2005)

Foundation Document, Fort Donelson National Battlefield, Kentucky-Tennessee (October 2020)

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Donelson National Battlefield, Kentucky-Tennessee (October 2019)

General C. F. Smith's Attack on the Rebel Right (Edwin C. Bearss, December 1959)

Geologic Map of Fort Donelson National Battlefield (September 2020)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Fort Donelson National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2020/2197 (Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, November 2020)

Historic Resource Study, Fort Donelson National Battlefield, Kentucky, Tennessee (Joseph E. Brent, W. Trent Spurlock, Elizabeth G. Heavrin and Lauren A. Poole, March 2020)

Historic Structure Report: Cemetery Lodge, Fort Donelson National Battlefield (Joseph K. Oppermann-Architect, 2019)

Historic Structure Report: Fort Donelson Cemetery Carriage House/Stable & Pump House, Fort Donelson National Battlefield (Joseph K. Oppermann, May 2011)

Historic Structures Report: The Dover Hotel, Dover, Tennessee, Part 1 — Historical Data (Edwin C. Bearss, December 1959)

Junior Ranger Activity Guide, Fort Donelson National Battlefield (2011; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Fort Donelson National Military Park and National Cemetery (Michael C. Livingston, undated)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Fort Donelson National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/FODO/NRR-2013/621 (Gary Sundin, Luke Worsham, Nathan P. Nibbelink, Michael T. Mengak and Gary Grossman, January 2013)

Newsletter: The Campaign for Fort Heiman, Fort Henry and Fort Donelson: The Sesquicentennial (2011)

Ozone and Foliar Injury Report for Cumberland Piedmont Network Parks Consisting of Cowpens NB, Fort Donelson NB, Mammoth Cave NP and Shiloh NMP: Annual Report 2009 NPS Natural Resource NPS/CUPN/NRDS-2010/110 (Johnathan Jernigan, Bobby C. Carson and Teresa Leibfried, November 2010)

Rivers and Rifles: The Role of Fort Heiman in the Western Theater of the Civil War (Timothy A. Parsons, Journal of Kentucky Archaeology 1(2):16-38, Winter 2012)

The Fall of Fort Henry (Edwin C. Bearss, The West Tennessee Historical Society, Vol. XVII, 1963)

The Significance of Forts Henry and Donelson in the Western Campaign, 1862 (Clarence Leroy Johnson, 1934)

Unconditional Surrender: The Fall of Fort Donelson (Edwin C. Bearss, 1962)

fodo/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025