|

Fort Stanwix National Monument New York |

|

NPS photo | |

Oneida Carrying Place

Six Miles that Changed the Course of America

For thousands of years the ancient trail that connects the Mohawk River and Wood Creek served as a vital link for people traveling between the Atlantic Ocean and Lake Ontario. Travelers used this well-worn route through Oneida Indian territory to carry trade goods and news, as well as diseases, to others far away. When Europeans arrived they called this trail the Oneida Carrying Place and inaugurated a significant period in American history—a period when nations fought for control of not only the Oneida Carrying Place, but the Mohawk Valley, the homelands of the Six Nations Confederacy, and the rich resources of North America as well. In this struggle Fort Stanwix would play a vital role.

Warrior, Six Nations Confederacy

The Oneida and Tuscarora nations, part of the Six Nations Confederacy, supported the Americans during the Revolution. The other four nations, the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, allied with the British. Mohawk warriors under Joseph Brant played a major role in the Battle of Oriskany.Private, 34th Regiment

Elements of the 34th Regiment of Foot accompanied St. Leger's little army and fought well during the siege of Fort Stanwix. Several companies were also with the Burgoyne expedition and were surrendered at Saratoga. After the siege, parts of the regiment participated in raids throughout the Mohawk Valley.Colonial Fur Trader

Dutch traders out of Albany offered the Six Nations tribes a variety of trade goods, including iron tomahawks, knives, axes, awls, fish hooks, cloth of various colors, woolen blankets, linen shirts, brass kettles, assorted jewelry and beads, guns, and powder.Private, 3rd New York

The 3rd New York Regiment, raised and trained by Col. Peter Gansevoort, had garrisoned Fort Stanwix (then called Fort Schuyler) since spring 1777. The regiment's stalwart defense of the fort, assisted by elements of the 9th Massachusetts Regiment and New York militia, won Gansevoort the thanks of Congress and a promotion.

A World War

The struggle began in the summer of 1754, when French and Virginia colonial troops clashed in southwestern Pennsylvania and set off what came to be called the French and Indian War. By 1756 the fighting had spread to Europe, where it was known as the Seven Years War. That same year, the French and their American Indian allies invaded the Mohawk Valley and began destroying British forts along the Oneida Carrying Place and German Flatts (Herkimer, N.Y.). In response, British Brig. Gen. John Stanwix was ordered to build a fort at the Oneida Carrying Place in 1758. Fort Stanwix ended French army invasions and provided a staging ground for British campaigns.

The Treaty of 1768

When the French and Indian War ended in 1763, France ceded all of its claims in North America east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain. American Indians, however, who had been allied with the French during the war, became increasingly dissatisfied with British policies and began a war of independence against them. Pontiac's Rebellion resulted in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, barring English settlement west of the Appalachians. In 1768, to settle conflicts between Indians and British settlers, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Sir William Johnson negotiated a treaty at the now-abandoned Fort Stanwix by which the Six Nations Confederacy agreed to cede lands east and south of the Ohio River. This angered other tribes who lived on these lands, and set the stage for future conflicts.

The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolution encompassed an eight-year span from Lexington and Concord in 1775 to the Treaty of Paris in 1783. In 1776, as the Continental Congress debated national independence, they ordered Gen. George Washington to have Fort Stanwix rebuilt to protect the emerging nation's northwest border and to secure a foothold for future westward expansion. The fort was renamed Fort Schuyler in honor of Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, commander of the Army's Northern Department.

1777: The Turning Point of the War

In the summer of 1777 British Lt. Col. Barry St. Leger (bearing the temporary rank of brigadier general) led an army into the Mohawk Valley as part of Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne's plan to control New York state. This army consisted of about 800 British, German, and Canadian soldiers, loyalists, and 800 American Indian warriors from New York and the Great Lakes region. Finding Fort Stanwix strongly garrisoned by almost 800 Continental soldiers commanded by Col. Peter Gansevoort, St. Leger laid siege to the fort on August 3.

On August 6 the Tryon County Militia under Brig. Gen. Nicholas Herkimer, en route to aid Fort Stanwix, was ambushed by loyalists and Indians near the Oneida village of Oriska. The Battle of Oriskany, which forced the militia to withdraw, was fought between family members, friends, and neighbors. The people of the Six Nations Confederacy also fought against one another, upending a peace that had bound them together for centuries. During the battle, Lt. Col. Marinus Willett, Gansevoort's second in command, led a sortie from the fort and captured a number of enemy prisoners, destroyed their camps, and brought 21 wagonloads of supplies into the fort. The siege ended on August 23, when Continentals under Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold arrived to reinforce the fort's garrison. The victory at Fort Stanwix, coupled with Burgoyne's defeat and surrender at Saratoga, led directly to the alliances between the United States, France, and the Netherlands.

The Arrogant Peace

The American Revolutionary War ended in 1783, but the United States and American Indians continued fighting. To end the war in New York, the United States negotiated the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix with the Six Nations Confederacy. The United States dictated the terms of this treaty, took American Indian hostages until all prisoners of war were returned, and coerced representatives from the Six Nations into signing the treaty. The Six Nations were also forced to cede land claims to Ohio and western Pennsylvania, which renewed westward expansion. Additionally, American Indian people were recognized as belonging to sovereign nations within the boundaries of the United States. The 1784 treaty led directly to Ohio's American Indian War of the 1780s and '90s.

Treaties and Councils of 1788 and 1790

After the American Revolution, the site of Fort Stanwix continued to be used for American Indian relations. Four land deals were negotiated here by the state of New York with the Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga without the approval of the federal government. These land deals were later acknowledged in the federal 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua. Every June 1 for years afterward the Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga people came to Fort Stanwix with representatives from New York state to receive their annual payments for the land. As a result, the land opened by the American Indian-New York state deals allowed canals to be dug, ultimately leading to the opening of the Erie Canal in 1827.

The Saratoga Campaign, June-October 1777

The Saratoga Campaign was the brainchild of Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne, who believed the American Revolution could be ended by splitting the colonies along the Hudson River. His plan was to advance south from Canada, up Lake Champlain, capture Fort Ticonderoga, and then march south along the Hudson to Albany. There he would join Sir William Howe, advancing north from New York City, and Barry St. Leger, coming east along the Mohawk River. Howe, however, became engaged in a campaign to capture Philadelphia and never reached Albany, and St. Leger became entangled in the futile 21-day siege of Fort Stanwix and was forced to return to Canada.

After capturing Ticonderoga with an ease and speed that shook patriot morale, Burgoyne continued his march south, defeating American troops at Hubbardton and forcing the evacuation of Forts Anne and Edward. Then his luck began to run out. A column of Hessians (German mercenaries) he sent to raid Bennington was defeated by troops under Brig. Gen. John Stark and Lt. Col. Seth Warner. Continuing southward, Burgoyne crossed the Hudson and halted his troops near present-day Stillwater, where the Americans under Horatio Gates, who had replaced Philip Schuyler as American commander, had taken up position on Bemis Heights. Burgoyne tried to break through the American lines at Freeman's Farm (Sept. 19) and at Bemis Heights (Oct. 7). Both attempts failed, and the British commander, finding himself outnumbered and surrounded and unable to retreat, surrendered on Oct. 17, 1777.

Key Events in Fort Stanwix History

1758

British build Fort Stanwix, from which troops successfully capture

French forts at Kingston, Ontario (1758), Oswego and Niagara (1759), and

St. Lawrence River and Montreal (1760)

1768

Boundary Line Treaty negotiated at Fort Stanwix with Six Nations tribes

opens Indian lands east and south of Allegheny and Ohio rivers to

settlement. Treaty angers other tribes living on these lands.

1777

Siege of Fort Stanwix begins August 3. Gansevoort vows to hold the fort

"to the last extremity." St. Leger abandons siege after 21 days as

American reinforcements approach.

Battle of Oriskany, August 6. British and Indians ambush 800 militia under Nicholas Herkimer, repulsing an attempt to relieve Fort Stanwix. Troops from Fort Stanwix loot loyalist and Indian camps.

1779

Troops led by Gens. John Sullivan and James Clinton destroy Onondaga

towns in the heart of Six Nations country in retaliation for raids in

the Mohawk Valley. Indian hostility intensifies.

1784

Treaty signed at Fort Stanwix ends war with those Six Nations tribes

allied with the British during the war and forces them to give up all

claims to lands west of New York and north of the Ohio River.

1788

New York state negotiates land deals with Oneidas and Onondagas at Fort

Stanwix, gaining large tracts of Indian land and challenging both

federal authority and Indian sovereignty in the process.

1790

Onondaga and Cayuga people confirm negotiated land deals with New York

state at Fort Stanwix. Much of the land acquired was sold to pay war

debts or granted to soldiers in lieu of back pay.

Exploring the Fort

Willett Center

Start here for an orientation to Fort Stanwix and the American Revolution in the

Mohawk Valley. Explore interactive programs, shop for one-of-a-kind gifts and

souvenirs.

Drawbridge

It is not known what type of drawbridge Fort Stanwix possessed. This

type was commonly used at the time. Operating on a counterweight system,

the 1,200-lb. weights on each side, started by manpower, would roll down

the track to bring the bridge up. To lower the bridge, it is believed

that heavy poles were used to push the bridge down until the weight of

the bridge brought the weights back up to the top of the tracks.

Southeast Casemate

This structure was used as soldiers' barracks. The name by the door

(Jansen) denotes the company commander. The long straw-filled beds,

called "cribs," slept 10 to 12 men side by side.

Southeast Bastion

The fort's bakery was located under this bastion. Bread was a mainstay

of the soldiers' diet, and each soldier was supposed to receive one

pound of bread or flour per day. A large opening in the bastion wall was

the entryway to the Necessary (toilet), which has not been

reconstructed.

Storehouse

This building was originally used as a storage area for supplies and may

have contained the Quartermaster's room as well. Today the public

restrooms are located here.

East Barracks

This complex housed sparsely furnished officers' quarters, workmen's

quarters, sutler's quarters, soldiers' quarters for companies commanded

by DeWitt and Bleeker, and junior officers' quarters.

Sally Port

The sally port, common to forts like Stanwix, was used to move small

parties of soldiers out of the fort under cover to, among other things,

replenish the water supply from the stream just outside the fort. Lt.

Colonel Willett used it to sneak through the British lines to get help

during the siege. The casemates on either side of the sally port served

as barracks for soldiers.

Northeast Bastion

At the time of the siege, this bastion was not completed. Due to this

weakness the British concentrated their early siege operations against

this point. The British cannon were placed about 600 yards to the north,

about where the tall, red brick building in the distance stands today.

The main encampment of St. Leger's army was just beyond that point.

Officers' Quarters

The combination of lack of space and bedding often led to the situation

represented here: simple soldiers' bunks and little in the way of

furnishings officers would have been accustomed to. From four to eight

officers might have shared this space during the siege.

Artillery Officer's Quarters

During the siege these quarters were occupied by Capt. Lieut. Joseph

Savage, who commanded the 30-man artillery unit composed primarily of

men from Massachusetts and Connecticut.

Commandant's Quarters

Col. Peter Gansevoort would have occupied this room. As commanding

officer's quarters, they were probably the most lavishly furnished.

Gansevoort also had more variety in his food, writing of eating "veal,

pigeons, and fish of different sorts."

Staff Room/Dining Room

During the day these quarters served as both an office for Colonel

Gansevoort and a staff room for officers. In the evening it could be

used as an officers' dining room and a place for their social

gatherings.

Officers'Quarters

Normally two to three officers would share a room this size. Its empty

appearance represents what fort quarters might have looked like when the

garrison was changing from one regiment to another.

Hearth Room

Originally an officer's quarters, this room now preserves the

foundations of an original fireplace uncovered during archeological

excavations in the 1970s.

Northwest Bastion

The magazine located beneath this bastion made it a target during siege

operations as the British attempted to destroy the fort's powder

supply.

West Casemate

Originally this, too, served as soldiers' barracks, furnished with the

cribs shown in the Southeast Casemate.

West Barracks

Originally this, too, served as soldiers' quarters for the company

commanded by Gregg. Today the building serves as a ranger station and

offers a short film about what life was like for the Americans during

the Revolution.

Southwest Bastion

Underneath this bastion, on which the flagpole currently stands, lies a

makeshift hospital where soldiers were treated. A variety of medical

tools are on display.

Southwest Casemate

This area served as living quarters for the fort's civilian workmen. It

currently houses park offices and is not open to the public.

The Fort Today

Guide to Fort Structures

Fort Stanwix appears below much as it did during the Revolutionary War. The City of Rome and the National Park Service partnered to rebuild a faithful replica of the original fort in 1976, using many original plans and documents. The headquarters building, guardhouse, sally port, necessary, and ravelin, however, have not been reconstructed.

Berm A narrow space between the parapet and the ditch, intended to prevent the earth from rolling into the ditch.

Bastion The projecting angles or corners of the fort.

Casemate Log buildings constructed against the interior walls of the fort to store supplies or to house men.

Covered Way A kind of road which runs around the ditch and is protected by a small parapet created by the glacis. It was used to move light artillery and troops around the fort.

Curtain Wall That part of the fortification that connects the bastions.

Ditch An excavation around part or all of the walls of a fort to hinder the advance of an attacker.

Embrasure An opening in the parapet through which cannon were fired. The widening angles allowed a sweeping fire.

Fraise A palisade of sharpened wooden stakes projecting outward in a horizontal fashion from the rampart to prevent an enemy from taking the fort by surprise.

Glacis A gently sloping earthwork around the fort stretching from the covered way toward the surrounding country.

Parapet A breastwork raised atop the rampart designed to protect the fort's soldiers and armament from enemy fire.

Sentry Box A small structure built atop the parapet of each bastion to shelter the sentry during inclement weather.

Things You Should Know

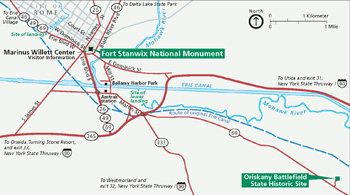

(click for larger map) |

The entrance gate to the fort requires a short walk from the Marinus Willett Center. Three short trails encircle the fort. One follows a portion of the Oneida Carrying Place. The other two help interpret the events of the siege of 1777. Park rangers conduct regularly scheduled interpretive programs daily, averaging 45 minutes in length. Check with the ranger on duty in the visitor center for times and locations of all programs offered that day. The park is accessible to people with disabilities, and many programs are accessible to those who are visually impaired. Staff is available to provide assistance.

Because the fort is an accurate reconstruction, there are hazards that require your alertness. The grounds in and around the fort are often rough and uneven, so please walk carefully. Many areas of the fort are made of wood; be mindful of splinters. Keep children off the walls and cannon and out of the fireplaces, and follow the instructions during weapon-firing demonstrations. There are no picknicking facilities at the fort. Pets must be leashed at all times. Do not smoke inside the buildings.

To Preserve and Interpret

Fort Stanwix National Monument tells a significant part of a complex story in American history. Many groups and agencies, both public and private, in New York state and throughout the eastern United States, work with the park to tell aspects of our shared heritage and preserve related historic sites. To better understand Fort Stanwix and colonial America's history, visit the partner sites, from local historical societies to state and national parks. Specific information about the park's partners may be obtained from park staff.

The Marinus Willett Collection Management and Education Center, opened in 2005, is the result of partnerships between the National Park Service, City of Rome, Oneida County, State of New York, and Oneida Indian Nation. The Center provides visitor orientation and exhibits, as well as state-of-the-art storage space for more than 400,000 artifacts in the park's museum collections.

All Roads Lead to Rome

Fort Stanwix is located in downtown Rome, N.Y., at the corner of James Street and Erie Boulevard. The Willett Center and the fort are open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., except Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1. All major state routes through Rome (26, 46, 49, 69, and 365) pass within sight of the Monument. To get to Rome from the New York Thruway, take exit 32 at Westmoreland to N.Y. 233 north to N.Y. 365 west, and follow the signs to downtown Rome. City parking is available within sight of the Monument. The bus terminal on Liberty Street is within two blocks of the site. The Amtrak railroad station at Martin Street and Route 233 is within a mile of the site. The nearest commercial airport is in Syracuse, N.Y.

Source: NPS Brochure (2005)

Documents

1779 Orderly Book (Frank Balduggi, 1997)

Administrative History Report (1923-1976), Fort Stanwix National Monument (William N. Jackson, September 13, 1985)

Administrative History Report (1923-1976), Fort Stanwix National Monument (William N. Jackson, April 21, 1992)

An Analysis of Faunal Remains from Fort Stanwix, New York: 1758-1781 (Jamie Hippensteel, Master's Thesis Indiana University of Pennsylvania, August 2016)

Battlefield Delineation: Siege of Fort Stanwix and Battle of Oriskany, Battlefield KOCOA Assessment and Mapping Project (Michael Jacobson, September 12, 2013)

Casemates and Cannonballs: Archeological Investigations at Fort Stanwix National Monument Publications in Archeology 14 (Lee Hanson and Dick Ping Hsu, 1975)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Fort Stanwix, Fort Stanwix National Monument (1999)

Final General Management Plan & Final Environmental Impact Statement, Fort Stanwix National Monument (2009)

Finding Aid: Fort Stanwix National Monument Resource Management Records (1923-2012) (History Associates Inc., September 18, 2012)

Fort Stanwix and Our Flag (Marion Emma Tracy, 1914)

Fort Stanwix: Construction and Military History (John F. Luzader, 2001)

Fort Stanwix: History, Historic Furnishing, and Historic Structure Reports (HTML edition) Construction and Military History (John F. Luzader), Historic Furnishing Study (Louis Torres), Historic Structure Report (Orville W. Carroll) (1976)

Foundation Document, Fort Stanwix National Monument, New York (August 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Stanwix National Monument, New York (January 2016)

Historical considerations on the siege and defence of Fort Stanwix, in 1776 (Henry R. Schoolcraft, 1846)

Historic Furnishing Study, Fort Stanwix National Monument, New York (Louis Torress, August 1974)

History of a 19th Century Urban Complex on the Site of Fort Stanwix, Rome NY Selections from the Historic American Buildings Survey No. XV (Diana Steck Waite, 1972)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Fort Stanwix National Monument, 2003 (Daniel J. Stynes and Ya-Yen Sun, January 2005)

Interpretive Prospectus, Fort Stanwix National Monument, New York (July 1975)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, Fort Stanwix National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Mapping Complex Land Use Histories and Urban Renewal Using Ground Penetrating Radar: A Case Study from Fort Stanwix (Tyler Stumpf, Daniel P. Bigman and Dominic J. Day, extract from Remote Sensing, Vol. 13, 2021)

Marinus Willett Center Final Environmental Assessment, Fort Stanwix National Monument (January 2003)

Master Plan, Fort Stanwix National Monument (1967)

Mitigation Report for 2013 Monitoring and Excavations Related to the Fire Suppression and Parade Ground Replacement Projects (PEPC Project #29475), Fort Stanwix National Monument, Rome, NY (Amy Roache-Fedchencko, February 2014)

Mohawk Valley Battlefield Ethnography, Phase II: The "Western Indians" and the Mississaugas Final Report (Joy A. Bilharz, March 2002)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Fort Stanwix (Charles E. Shedd, Jr., February 14, 1962)

Oriskany: A Place of Great Sadness, A Mohawk Valley Battlefield Ethnography, Fort Stanwix National Monument Special Ethnographic Report (Joy Bilharz, February 2009)

Outhouses in Rome, New York (Lee Hanson, extract from Northeast Historical Archaeology, Vol. 3, 1974)

Overview of Priority Botanical Materials (Jessica Bowes, March 2016)

Reconstructing the Past, Partnering for the Future: An Administrative History of Fort Stanwix National Monument (Joan M. Zenzen, June 2004)

Roseboom Ledgers (Myndert and Barent Rooseboom, 1757-1775)

Teapots in the Tempest: Ceramics and Military Order at 18th-Century Fort Stanwix (©Elizabeth Anne Scholz, Master's Thesis College of William and Mary, August 2016)

The British ministry and the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (Clarence Walworth Alvord, 1909)

The Marinus Willett Collections Management and Education Center (Date Unknown)

"We Took to Ourselves Liberty": A Historic Resource Study of Sites Relating to the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Oneida County and Beyond (Judith Wellman w/Jan DeAmicis, Mary Hayes Gordon, Jessica Harney, Deirdre Sinnott and Milton Sernett, January 2022)

fost/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025