|

Fort Union

Administrative History |

|

INTRODUCTION

Few places today inspire imagination about the American frontier experience as does Fort Union National Monument. Located in the Mora Valley in northeastern New Mexico, the 720-acre National Park Service domain contains an array of cultural and natural resources. Its principal features--the ruts of the Santa Fe Trail, the ruins of the Fort Union military post, and the dazzling prairie scenery--daily attract American travelers. The place has been serving society as a museum of the past, a classroom in the present, and a model for the future. Certainly it deserves the honor of a national treasure.

With the annexation of northern Mexico in 1848, the United States assumed the entire burden of protecting the Santa Fe Trail. The frequent Indian raids on travelers and settlers brought 1,300 soldiers to New Mexico. In 1851, Lt. Col. Edwin V. Sumner, the commander of the Department of New Mexico, decided to establish Fort Union at the junction of the two branches of the Santa Fe Trail in order to provide more effective protection for the region. With its troops constantly repelling Indian raiders, the fort soon won fame as the guardian of the Santa Fe Trail. When the Civil War broke out, the Confederacy attempted to seize the post as part of a plan to take New Mexico, carry the war into Colorado Territory, and threaten California. But the Confederates' dream died at the battle of Glorieta Pass, where Union soldiers from Fort Union were victorious over the invading Southern columns. In the quarter-century after the war, Fort Union contrived to help American settlers and played a key role in many of the Indian wars. At one time, it was the largest military post west of the Mississippi River. In 1891, a year after the traditional closing of the frontier, Fort Union was abandoned.

In the following 65 years, Fort Union suffered at the hands of a private owner, Union Land and Grazing Company. Because the company had little interest in using the buildings, the fort was left unattended. Consequently, foraging cattle, salvagers, and the merciless course of nature worked together and quickly turned the fort into ruins. In 1929, the Free Masons in Las Vegas became the first group to attempt to save the ruins of Fort Union, the birthplace of their lodge. The Masons took their cause to Congress and convinced Rep. Albert Simms of New Mexico to introduce a bill asking the federal government to preserve the historic site. The bill never reached the floor to face a vote. In the next 25 years, New Mexicans tried unsuccessfully several times to get congressional protection of the old fort. The land owner's stiff opposition easily defeated their efforts. Beginning in the early 1950s, the campaign for the preservation of the fort gained momentum. With public support, Rep. John Dempsey of New Mexico again submitted a bill to establish Fort Union National Monument to the 82nd Congress. H.R. 1005 passed both houses, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed it into law on June 28, 1954. Public Law 430 established Fort Union National Monument.

After Union Land and Grazing Company donated the land, the National Park Service officially took control of Fort Union. On June 8, 1956, the monument opened to the public. Meanwhile, the Park Service began to implement a comprehensive program that included the excavation, preservation, and interpretation of the fort's ruins. Within three years, Fort Union developed into a fully operational monument and held its dedication ceremony on June 14, 1959. With the exception of the period from 1980 to 1987, when its administration was combined with that of Capulin Mountain National Monument, Fort Union has been managed independently.

|

|

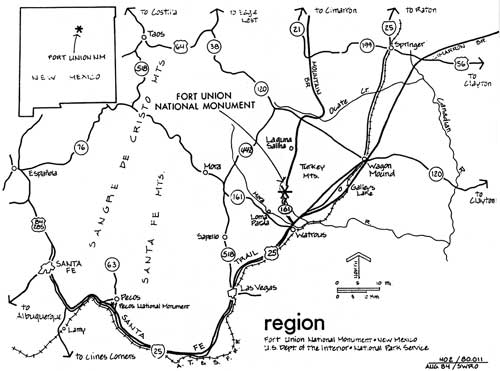

Figure 1. Region: Fort Union National Monument (click on map for a larger image) |

Through the park's history, the preservation of the ruins has posed the greatest challenge to management. Although the aged adobe walls have kept shrinking, the park staff has never yielded in its determination to preserve the ruins and has improved preservation methods. Also, the park administration has made great efforts to interpret the historic site. After nearly two decades of applying traditional interpretive methods such as museum exhibits and written explanations, park officials initiated a living history program, which set the tone for future interpretive activities. During the first 36 years, the management of the park's cultural and natural resources was remarkable.

Fort Union's rich past attracts many scholars and researchers, but an overwhelming number of them show interest only in the fort's first four decades, from 1851 to 1891, when it served as a frontier post. Without denying the significant role that the fort played in winning the American West, there are also numerous fascinating stories about the place after its glorious frontier days, particularly in the last 36 years. This period deserves a comprehensive study that is long overdue. As a Western American history fellow at the University of New Mexico, I happily accepted the Park Service's assignment to bring the history of Fort Union up to the present time. The existence of enough books and articles about the Fort Union Military Post advises me not to spend too much ink on the fort's first 100 years. My work deals primarily with the period from 1956 to 1991, in other words, the administrative history of Fort Union National Monument.

This work has benefited from the assistance of many people. I would like to thank Superintendent Harry Myers and his staff, including T. J. Sperry, Frank Torres, Debbie Archuleta, Albert Dominguez, Teddy Garcia, Bob Martinez, Manuel de Herrera, and others, for their patience and cooperation throughout the course of this project. They not only answered my numerous questions and directed me to proper documents but also provided me with a pleasant research environment and constant friendship. In particular, Myers and Sperry read every chapter of the first draft; their critical but constructive comments helped the project move in the right direction. Indeed, I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with them at Fort Union.

Undoubtedly, my endeavor could not have succeeded without the support of the National Park Service Southwest Regional Office. Its special funds made this project possible. During my research trips, Regional Librarian Amalin Ferguson and librarian Cordelia Friedman showed their willingness to help me to find needed documents. Here, I express my deep appreciation. However, the person who has influenced me most is Regional Historian Neil Mangum. Overseeing the project from the very beginning, he has offered insightful criticism and thoughtful opinions. His frequent visits to the University of New Mexico campus gave me more opportunities to improve my study.

Finally, I would like to thank many of my colleagues in the Department of History. Their moral support kept me working at a steady pace. Although Professor Paul Hutton was not directly involved in the project, his teaching and scholarship plus his communication skills were extremely helpful in the completion of the work. Three of these sincere friends and colleagues deserve special mention here. They are Jolane Culhane, Aaron P. Mahr, and Christopher Huggard, who have carefully corrected many writing mistakes in the manuscript. Jolane Culhane provided a major hand in the final editing of the paper. All of them have contributed to the study's success but I am fully responsible for any errors that remain.

|

|

Figure 2. Site Map: Fort Union National Monument (click on map for a larger image) |

This year is the hundredth anniversary of the close of the American frontier and Fort Union as a military post. It is a perfect time to commemorate those who won the West. Although my work has little to do with honoring the frontiersmen, it shows an appreciation of those who have preserved the historic site. They are keeping our frontier heritage alive.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foun/adhi/intro.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2001