|

Fort Union

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 1: A FRONTIER POST

|

|

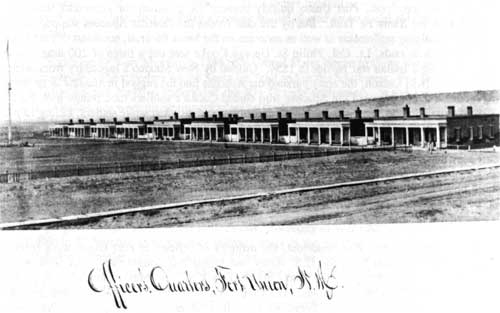

Figure 3. Fort Union was once the largest military post west of the

Mississippi River. Officers' Quarters in 1875. Courtesy of the National Archives. |

The ruins of Fort Union, New Mexico, stand as a monument to the American frontier experience. The Southwest became a meeting place for various migrants throughout our nation's history as people from all directions moved into the area and built their homes. Constant military conflict and continuous cultural exchange among different ethnic groups has made the region legendary in American folklore. As a military post established to protect travel and settlement from 1851 to 1891, Fort Union witnessed many fascinating events in the course of western American history. A century later, the site of the old fort remains as a vestige of the great American epic.

Fort Union National Monument is located in the Mora Valley in northeastern New Mexico at the westernmost edge of the Great Plains. On its way to join the Mora River, a southward flow of Wolf Creek softly touches the western boundary of the park. In the distance, the Turkey Mountains vigilantly guard its eastern border. Surrounded by a sea of grama grass, the park presents an authentic plains atmosphere even though it is only eight miles from the nearest town, Watrous, twenty-eight miles from Las Vegas, and ninety miles from Santa Fe. Despite its relative isolation, Fort Union is easily accessible from New Mexico Highway 161, which also links the fort to Interstate Highway 25 at Watrous.

At 6,700 feet, Fort Union has an environment conducive to abundant plant and animal life. The Mora Valley climate is mild without great extremes of heat or cold; the average annual temperature at the monument is 49.2 Fahrenheit. July has the highest monthly temperature at 69.7 Fahrenheit, and December the lowest at 33.1 Fahrenheit. Precipitation measures 18.01 inches per year. More than 80% of the annual precipitation comes between May and November. [1] Although it is in a semi-arid zone, the Mora Valley receives enough rainfall to support stands of ponderosa, which thrive on the mountain slopes. Juniper, piñon pine, and blue grama grass grow at lower elevations in the foothills. [2] In addition to the vegetation, more than 50 species of animals such as prairie dogs, rattlesnakes, Canada geese, and burrowing owls have also made their homes in the area. Occasionally, a few bald eagles visit the valley. [3] Lush pasturage, abundant timber, and numerous ponds make the Mora Valley a desirable spot for settlement.

Like most parts of northern New Mexico, the Mora Valley served as a refuge for at least five Indian tribes long before the arrival of Europeans. Navajos, Apaches, Utes, Kiowas, and Comanches either lived, passed through, or fought in the valley, but few written documents and little archeological evidence exists to retell the lives of these nomadic tribes.

By the mid-sixteenth century, life in this region began to change dramatically after European contact. With dreams of finding the seven cities of Golden Quivira, the Spanish Crown was first to encourage exploration of this vast new area. Francisco Vasquez de Coronado nearly reached the Mora Valley during his famous expedition of 1540-1542. After failing to discover gold, the Spaniards began to consider settling New Mexico. In 1598 the Spaniards built their first houses at San Juan near present day Española. Gradually, a chain of settlements emerged along the Rio Grande. Throughout the next 200 years, in fact, Santa Fe attracted many new immigrants, but on the east side of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, where the Mora Valley lay, there was little settlement until the late 1810s.

Leaving the northern frontier of New Spain unprotected, the Spanish unknowingly allowed Anglo-Americans to encroach into the area from the north. As early as 1802, a Pennsylvanian beaver trapper, James Purcell, adventured into New Mexico from Missouri via Colorado. In 1805, after running out of supplies and pelts, Purcell searched in New Mexico for other means of profit. He decided to mine gold, which he traded to local citizens for goods. Spanish officials in Santa Fe learned of Purcell's activities and ordered him to report for questioning as to his real intention. When he refused to comply with the order, they incarcerated him. He was detained until 1824. [4] Purcell became "the first American who had ever penetrated the immense wilds of Louisiana." Capt. Zebulon Pike of the 6th U.S. Infantry followed in Purcell's footsteps. Under the instruction of the United States a small military team moved west to reconnoiter a potential territory for expansion. Initiating his exploration in the Rocky Mountains in 1806, Pike and his soldiers reached the headwaters of the Rio Grande in Colorado's San Luis Valley by early 1807. Spanish dragoons, however, discovered the Americans and ordered them to Santa Fe, due to their violation of international boundaries. The Spanish finally released him in June 1807, and by 1810 his adventures were published as the Pike Journals. [5]

Early American adventurers like Purcell and Pike threatened the northern frontier of New Spain and created a struggle for dominance in the region. Pike, in particular, with his memoir, mobilized support among the American public. His writings informed Americans of the possibilities for investment. Yankee merchants immediately realized New Mexico's market potential for American goods, after reading that local people had to haul most of their commodities 2,000 miles from Veracruz, Mexico. In the same year that Pike told of his adventures, a revolution broke out in New Spain, which culminated with Mexico's independence in 1821.

Infant Mexico lost no time in welcoming American traders to Santa Fe and abandoning the old Spanish system, which had prohibited American traders in New Spain. Meanwhile American merchants did not hesitate to accept the "invitation" and to inaugurate the Santa Fe trade. With several other enterprising Missourians, William Becknell was one of the first American merchants to send mule pack-trains westward. He crossed 800 miles of prairie and arrived in Santa Fe in the fall of 1821. Governor Facundo Melgares warmly received Becknell and the other Missourians, expressing "a desire that the Americans would keep up an intercourse with that country." [6] The Mexicans were so interested in American trade that it led historian David Weber to write that "Americans were as eager to sell as Mexicans were to buy." [7]

This Santa Fe trade, as well as the Santa Fe Trail, would significantly shape the history of the Southwest. On his second trip to Santa Fe in the spring of 1822, Becknell blazed a short cut by way of the Cimarron River, thereby avoiding the mountainous Raton Pass. The Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail intersected the Mountain Branch in the Mora Valley. [8] In 1825 a military surveying party under George C. Sibley marked out a suitable route from Kansas to New Mexico. By 1830 the Santa Fe Trail, an international highway between Mexico and the U.S., had been established, producing an even greater volume of trade.

Situated at the junction of the two routes of the Santa Fe Trail, the Mora Valley, with both strategic and economic importance, quickly became a focal point of concern for Mexican authorities. The best way to defend an area was to populate it. As early as 1816, a few families of New Spain moved into the western Mora Valley on the eastern slope of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Since the dying Spanish regime was unable to protect all the settlers against attack by the Plains Indians, nobody dared to go farther east. Most of the rich valley remained unsettled. [9] However, the young Mexican government showed its anxieties to defend this area. In 1835 Albino Perez, governor of New Mexico, granted 827,621 acres of land including most of the valley to Jose Tapia and 75 others to initiate Mexican policies. [10] More settlers moved into the valley. The future site of Fort Union was at the center of the Mora Grant. In the next ten years, however, the valley sheltered more travelers than settlers since the Santa Fe trade was increasing at a magnificent rate. In dollars, the volume rose from $15,000 in 1822 to $450,000 in 1843. [11] By the eve of the Mexican War, Americans had become commonplace in the Mora Valley.

Soon the number of Americans was overwhelming. When war broke out in 1846 between the United States and Mexico, the Santa Fe Trail was transformed into a military road. Following the old wagon ruts that formed the trail, Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny led his conquering army swiftly into New Mexico and raised the United States flag without any resistance. On this journey, General Kearny and his troops camped one night near where Fort Union would later stand. [12] Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the United States annexed New Mexico and California in 1848, turning the Santa Fe Trail from an "international highway into a national highway," linking the new territory with the rest of the country. [13]

Alexander Barclay, an American frontiersman born in Britain, was one of the first persons to realize the strategic location of the Mora Valley. An increasing number of Kearny's baggage trains and the government's freight wagons passing through the region meant more services were needed along the road. Barclay, therefore, selected the junction of the Mora and Sapello rivers, about six miles south of where Fort Union was later built, for his trading post. On June 11, 1848, he "laid the first doby of fort and fired cannon...." [14] Although he maintained contact with the military leaders and local communities, Barclay struggled to make his venture a self-sufficient and financially rewarding enterprise. If Indian raiders left his cattle and horses alone and his post profited some what, Barclay hoped that in the future he could sell the fort to the United States government. [15] Like Bent's Fort, a center for Indian trade in Colorado, where he had served as superintendent, Barclay's trading station played an essential role in shaping the Santa Fe Trail.

|

|

Figure 4. Officers' Quarters, Post of Fort Union, in the

1870s. Courtesy of New Mexico Magazine |

With the acquisition of New Mexico in 1848, the United States began to carry the entire burden of protecting traders and travelers on the Santa Fe Trail and in the Southwest. For two and a half centuries Apaches and Navajos had raided the Rio Grande settlements, at the same time that Kiowas and Comanches were disrupting travelers on the Plains. The Indians were defending their homelands from the encroachment of Europeans. The federal government countered these raids by sending better than 10% of the army to the area. By 1851 almost 1,300 soldiers were stationed at eleven outposts in the Territory of New Mexico. [16] The post of Santa Fe served as the headquarters of the Ninth Military Department.

Although the number of soldiers in New Mexico was relatively high, their performance did not please military commanders. Military expenditures were greatly increased, yet there appeared to be little progress toward stopping the Indian raids. Secretary of War Charles M. Conrad asked Lt. Col. Edwin V. Sumner to consolidate military posts in the territory and to move the troops "more toward the frontier, near the Indians." [17] As soon as he arrived in Santa Fe and assumed command of the Department of New Mexico, Sumner issued Orders No. 21 to remove "the troops and public property" to a new location named Fort Union. [18] In his zeal to carry out the order, Colonel Sumner managed to transfer most of the properties in the department headquarters at Santa Fe to the site of the new post within twenty days. [19] He also consolidated troops from Las Vegas, Albuquerque, Socorro, El Paso, and other posts and stationed them at the new fort. [20]

As a frontier post, Fort Union was strategically situated near the junction of the Mountain and Cimarron branches of the Santa Fe Trail. Noticing the activities of Sumner's entourage, Alexander Barclay offered to sell his fort to the army. But the military refused his offer and chose to build its own post six miles north of Barclay's fort. At that time none of the commanders or the soldiers knew this "free" site was private property within the borders of the Mora Grant. These unchallenged squatters immediately started building the fort. By the end of the first year, more than thirty buildings had been erected at the base of West Mesa. In 1852, under Sumner's Special Orders No. 30, Fort Union's territory expanded to eight square miles. [21]

As a key military post, Fort Union quickly became the guardian for American traders and travelers on the Santa Fe Trail. But by the mid-1850s, the Jicarilla Apaches stepped up their raiding of outlying settlements as well as caravans on the Santa Fe Trail, northeast of Fort Union. To combat their raids, Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke sent out a force of 200 dragoons and infantry to fight Indian war parties in 1854. Guided by New Mexico's legendary frontiersman, Christopher [Kit] Carson, the army pursued the Apaches into the rugged mountains in an attempt to subdue them. [22] Many of the Apaches who eluded Cooke's soldiers took refuge with the Utes in southern Colorado. A few months later they united and attacked white settlers, killing 15 men. In 1855 the U.S. Army launched another extensive campaign that led to the Ute War of 1855. More than 500 soldiers, reinforced by the First Dragoons from Fort Union, fought the united Indian tribes, which sued for peace after several devastating battles. [23] With this temporary peace, the army shifted its attention to the Plains, where the elusive Kiowas and Comanches had been plundering settlers and travelers. During 1860-1861, the soldiers from Fort Union pushed these Indian tribes out of the territory. Hence, in its first ten years, Fort Union played a significant role in protecting the new American highway, the Santa Fe Trail.

In 1861 when the Civil War broke out, the majority of officers at Fort Union were from the South. They resigned from the U.S. Army and joined the Confederacy. As soon as they assumed their new allegiance, the rebels marched back to New Mexico and tried to seize all Union posts and the Colorado mines. The Confederates' invasion threatened Union control of the fort. The Union soldiers began to busy themselves constructing a massive earthen "fieldwork," later called the Star Fort, which was a mile east of the first fort and was designed to block the Santa Fe Trail against Confederate advance from the south. [24] In early 1862 the Confederates forced Union troops to evacuate Santa Fe and to take a defensive position at the Star Fort. At this crucial moment, the first Colorado Volunteer regiment, led by Col. John P. Slough, arrived in New Mexico. Between the Unionists and the Confederates lay Glorieta Pass, a rugged opening through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, where on March 28, 1862, the two armies fought the decisive battle of the Civil War in the far western theater. In three days Union troops had achieved a victory, and the Confederates retreated to Texas.

After the battle at Glorieta Pass, Fort Union received no further threat from the Confederates. The new commander of the Department of New Mexico, Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton, gave orders to build a new fort adjacent to the earthwork. The sprawling installation contained three parts: the Post, the Quartermaster Depot, and the Ordinance Depot. It took several hundred civilians five years, from 1863 to 1868, to complete construction. The new buildings at Fort Union were constructed of adobe brick, the walls standing on stone foundations and coated with plaster. The main structures had tin roofs, except the hospital, which was shingled. The military installation was the largest in New Mexico, and according to Inspector Andrew W. Evans, the most luxurious. [25]

In addition to normal military functions, the new fort, today called the Third Fort, became the army's supply center in New Mexico. In order to consolidate a number of the older forts in the region after the reunion, the army proposed to expand Fort Union into one of the largest posts in the West. The Fort Union Quartermaster Depot soon assumed the responsibilities of supplying other posts with nearly everything needed for their existence. As a British traveler observed in 1867, "Fort Union is a bustling place; it is the largest military establishment to be found on the Plains, and is the supply center" for "the forty or fifty lesser posts scattered all over the country within a radius of 500 miles...." [26]

|

|

Figure 5. Fort Union Depot served as the Army supply center for the

Department of New Mexico. The Mechanic's Corral, Fort Union Depot, in

1866. Courtesy of the National Archives. |

In the quarter-century after the Civil War, Americans conquered their last frontier by settling on the Great Plains. The greatest barrier to American settlement was the Plains Indians such as the Kiowas, Comanches, Cheyennes, and Apaches, who had resisted white encroachment. To confine them to a designated area required intensive military campaigns. During that period, Fort Union participated in several large operations against the Indians: the Mescalero Scout of 1867, the Campaign of 1868, and the Red River War of 1874. As the largest military post west of the Mississippi during the period from 1865 to 1875, Fort Union helped the nation to subdue the Indian war parties.

In September 1867, a Mescalero Apache war party ran off 150 head of stock near Mora. With several dozen soldiers from the Third Cavalry, Capt. Francis H. Wilson immediately rode out of Fort Union in pursuit. On October 18, the soldiers finally caught up with the raiders in western Texas. After a three-hour battle in Dog Canyon, the army destroyed a winter camp of 400 Mescaleros and drove the warriors into the mountains. Fort Union played a memorable role in the Mescalero Scout, in which the raiders received a severe blow. [27]

Replacing the Mescaleros, the Plains Indians once more drew the attention of Fort Union from the east. In the fall of 1868, Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan decided to launch a winter campaign against the Kiowas and Comanches. He planned to have four columns converge on the winter campground of the Indians. Participating in this unprecedented military operation, Fort Union sent its troops down the Canadian River as a western thrust to encircle the Indians. Led by Maj. Andrew W. Evans, the New Mexico column engaged in several battles in western Texas and broke the resistance of the Plains tribes. Some Indians yielded to government demands and accepted the hated reservation system. [28]

Beginning in the early 1870s, some recovered Kiowas and Comanches joined by a few Cheyennes and Arapahos increased their raids on settlements on the northern frontier of Texas. General Sheridan decided to repeat his strategy by fighting the tribes from different directions. One of the five converging columns came from New Mexico. Under the command of Maj. William E. Price, three troops of the Eighth Cavalry left Fort Union on August 20, 1874, and scoured the valleys of the Canadian and Washita rivers. At the end of the year, the Red River War resulted in victory; the defeated tribes of the southern Plains never again posed a threat to settlers. [29]

In its forty years (1851-1891) as a frontier post, Fort Union often had to defend itself in the courtroom as well as on the battlefield. When the U.S. Army built Fort Union in the Mora Valley in 1851, the soldiers were unaware that they had encroached on private property, which was part of the Mora Grant. The following year Colonel Sumner expanded the fort to an area of eight square miles by claiming the site as a military reservation. In 1868 President Andrew Johnson went even further to declare a timber reservation encompassing the entire range of the Turkey Mountains and comprising an area of fifty-three square miles, as part of the fort. [30]

The claimants of the Mora Grant immediately challenged the government squatters and took the case to court. By the mid-1850s the case reached Congress. In the next two decades the government did not give any favorable decision to the claimants, until 1876 when the Surveyor-General of New Mexico reported that Fort Union was "no doubt" located in the Mora Grant. But the army was unwilling to move to another place or to compensate the claimants because of the cost. Thus, the Secretary of War took "a prudential measure," protesting the decision of the acting commissioner of the General Land Office. He argued that the military had improved the area and should not give it up without compensation. [31] This stalling tactic worked; the army stayed at the fort until its demise in 1891, not paying a single penny to legitimate owners.

The transcontinental railroad symbolized the conquest of the frontier. On Independence Day 1879, the first locomotive of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad steamed into Las Vegas. The railroad opened a new era in the Southwest by replacing the old Santa Fe Trail as the main artery of commerce. During the 1880s Fort Union lost its military importance and commercial usefulness due to the defeat of the Indians and the arrival of the railroad. The number of soldiers stationed at the fort declined significantly. The fort no longer had any great military value. Once the superintendent of Indian schools proposed to acquire the vacant arsenal buildings for the establishment of an Indian manual labor school. Certainly, the heyday of Fort Union had passed. [32] In 1890, with the census reports' symbolic closing of the frontier, the War Department decided to abandon many of the old frontier posts, including Fort Union. As a result, a year later Fort Union was officially closed.

As a military post to protect travel and settlement for 40 years, 1851 to 1891, Fort Union played a key role in shaping the destiny of the Southwest. During the first decade of its existence the fort stood as the guardian of the Santa Fe Trail. The fort acted as a federal presence in the Territory of New Mexico. The Civil War added to the fort's fame at the battle of Glorieta Pass, where Union soldiers stopped the invading Southern columns. In the quarter-century after the reunion, Fort Union contrived to help American settlers and devoted the rest of its life to the conquest of American frontier. As historian Robert Utley praised, "The ruins of Fort Union graphically commemorate the achievements of the men who won the West." [33]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foun/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2001