|

Fort Union

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 2: FROM RUINS TO A NATIONAL MONUMENT

|

|

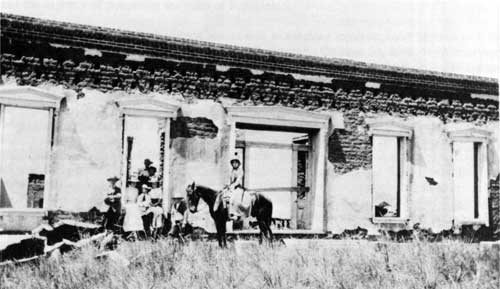

Figure 6. After the abandonment of Fort Union in 1891, the place was

open to tourists and looters. Their activities accelerated the

deterioration of the buildings. By 1912 Officers' Quarters had already

become ruins. Courtesy of Katherine Hand. |

On February 21, 1891, singing "There's a Land that is Fairer than This," the Tenth Infantry marched out from Fort Union for good. One non-commissioned person stayed as a caretaker. [1] Three years later, the War Department relinquished claim to the land on which Fort Union stood. Finally both the land and title reverted to the original owners of the Mora Land Grant.

By then the extensive ranchlands surrounding Fort Union had passed into the hands of the descendants of Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler of Civil War fame. He purchased the lands from the claimants of the Mora Grant in the mid-1870s. When the military abandoned Fort Union, the Butler-Ames Cattle Company, (later the Union Land and Grazing Company, formed in 1885), inherited the title to the fort. Initially, the Butler-Ames Cattle Company tried to utilize the abandoned fort for economic and social purposes. On January 12, 1895, Paul Butler, Blanches Butler Ames, and Adelbert Ames, owners of the company, entered into a contract with Dr. William D. Gentry of Illinois to lease the buildings to be used as a sanitarium. According to the contract, the owners were responsible for repairing the buildings. For reasons unknown, the contract was never fulfilled. In the next 60 years, the company made no attempt to use the fort except to open it to cattle grazing. [2]

Although the Butler-Ames Cattle Company had little interest in reinhabiting the buildings, quite a few people did make an effort to live in the fort. After Fort Union's abandonment, several soldiers managed to stay there and ran cattle in the area. Nobody ever attempted to evict the squatters, who later moved away. [3] Since troops left almost everything there, Fort Union contained a large quantity of lumber and other construction materials, which interested local residents from the nearby communities of Loma Parda and Watrous. Whenever a family wanted to repair or even to build a house, the people went to the ruins of Fort Union to find what they needed. In Watrous, almost all the windows, doors, and vigas in the houses came from Fort Union. [4] They first took materials from the officers' and company quarters, then from the mechanics' corral, followed by the warehouses, and finally the hospital. Also, curiosity seekers often took items home. Rising above the open prairie, Fort Union invited scavengers and souvenir hunters.

Mother nature was as destructive as vandals. At the beginning unskilled soldiers had built the fort with adobe bricks and unseasoned, unhewn, and unbarked pine logs. Consequently, it decayed rapidly. The buildings of Fort Union required constant repair even during the period of occupation. A military wife, Genevieve LaTourrette, later recalled, "Toward the latter years at Fort Union, the quarters needed renovating badly....Roofs were leaking in the quarters to the extent that we went around with umbrellas." [5] The adobe walls, in particular, were vulnerable to all kinds of weather. After the fort's abandonment, the condition of the buildings deteriorated faster than ever. Along with vandalism, the sun, rain, snow, and wind turned the fort to ruins.

The first serious attempt to preserve the ruins of Fort Union as a historic site came in 1929 when the Freemasons in Las Vegas, New Mexico, called for the establishment of a national monument. Fort Union was the birthplace of two Masonic Lodges--Chapman Lodge No. 95 (later Chapman Lodge No. 2) and Union Lodge No. 480 (later Union Lodge No. 4). On March 28, 1862, some zealous Masons set up a new lodge under the dispensation of the Grand Lodge of Missouri. They named it Chapman Lodge in honor of Lt. Col. William Chapman, who was then in command of Fort Union. Many officers and enlisted men belonged to the lodge and attended the meetings regularly in the "House of the Good Templars." In 1867 the Army requested that the lodge be moved outside the government reservation, apparently for military reasons. The lodge was moved to Las Vegas. In 1874 another group of Masons asked for permission to establish a Masonic Lodge at Fort Union. This time they called it Union Lodge, which met in the fort until 1891. Then it moved to Watrous. [6]

With a purpose to enshrine the birthplace of the Chapman Lodge and the Union Lodge, Masons in Las Vegas became the first to ask for preservation of the ruins of Fort Union. On January 23, 1929, they appointed a four-person committee chaired by W. J. Lucas to "have Fort Union declared a national monument." [7] Taking the issue to Santa Fe, the committee successfully persuaded the state legislature to pass a joint resolution to petition Congress. In Joint Resolution No. 12 of 1929 the legislature of the State of New Mexico respectfully petitioned "the Congress of the United States to set aside this historic site and to preserve and maintain Fort Union as a National Monument." [8]

The campaign for the Fort Union National Monument soon gained support among the lawmakers of New Mexico. On April 20, 1930, Rep. Albert Gallatin Simms of New Mexico introduced a bill (H.R. 11146) in the 71st Congress, asking the Federal Government "to provide for the study, investigation, and survey, for commemorative purposes, of the Glorieta Pass, Pigeon Ranch, Apache Canyon battlefields, and of Old Fort Union in the State of New Mexico." [9] At this time, the nation was suffering the economic woes of the Great Depression. It was hard to imagine that Washington would pay much attention to the ruins of an old fort in New Mexico. Not surprisingly, the bill died in the House Committee on Military Affairs.

Even though the Great Depression temporarily halted work toward the preservation of Fort Union, New Mexico did not give up their struggle for a national monument. Articles on Fort Union frequently appeared in New Mexico's newspapers and magazines. In the mid-1930s the National Park Service also reintroduced hope for the preservation of the fort by showing interest in the ruins of Fort Union. Roger W. Toll of Rocky Mountain National Park drove down to the Mora Valley to inspect the "Proposed Fort Union National Monument" in December 1935. He took some notes and photographs and collected a few published articles. On March 24, 1936, the superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park forwarded Toll's report and gatherings to Washington. [10] Toll's efforts provided the National Park Service with a first-hand account of the condition of the ruins. These actions also gave renewed hope that the fort would be salvaged for future generations to learn from and enjoy.

After receiving Toll's initial account, the National Park Service decided to make an additional study of the fort. In 1937 Edward Steere of the Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings was assigned to write a frontier history of Fort Union. Within a year he finished a 108-page report entitled "Fort Union, Its Economic and Military History." [11] In this well-researched paper, he indicated that Fort Union played an important role in the development of the territory of New Mexico. The study not only provided the Park Service with the first comprehensive history of Fort Union, but also supplied the administrators with information on the urgency for preservation of the site.

With support from Washington, the National Park Service's Region Three Office in Santa Fe soon organized an investigative trip to Fort Union. On May 9, 1939, Hillory A. Tolson, director of Region Three, led a "reconnaissance party" to the old fort. This well-balanced team included George Hammond, dean of the Graduate School at the University of New Mexico, Herbert O. Brayer, assistant director of the Coronado Quarto Centennial Commission, Aubrey Neasham, regional historian of Region Three, Kenneth F. Woodman, statistician of the Park Service, and Charles A. Richey, assistant landscape architect of Region Three. The purpose of this trip was to investigate possible routes to the fort. [12] Since the area had not been accurately surveyed, it was necessary for Richey and his assistant to return on the following day in order to determine the boundary and acreage of the fort. [13] This investigative trip also helped to determine the willingness of the Park Service to establish a national monument at Fort Union.

Five days later, Tolson sent a contingent (Hammond, Brayer, and Neasham) to meet with Edward B. Wheeler, agent for the Union Land and Grazing Company, at his office in Las Vegas, New Mexico. [14] Wheeler had bitterly opposed government intervention because he had claimed $100,000 damages for illegal timber cutting on the estate of the Butler Cattle Company. This claim was based on the idea that the United States Forest Service had incorrectly surveyed the area. Both the House and Senate once voted for compensation, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt vetoed it. [15] Despite Wheeler's hostile feeling, the Park Service delegation persuaded him to cooperate with the government. At the meeting Wheeler agreed to recommend that the Union Land and Grazing Company donate to the United States Government approximately 1,000 acres of land for the establishment of a national monument. He also agreed to give a 200-foot wide right-of-way for an entrance road to the fort from Highway 85 (present day Interstate 25). [16] In return, the government agreed to fence the donated land, build a house for the company agent, furnish water and electricity, and construct at least three underpasses on the road for cattle passage. The agreement included a reversionary clause saying, "if at any time the land is not used by the United States as a national monument or reservation, title shall revert to the Union Land and Grazing Company or to its successor." [17] In the coming years, this clause was to prove the greatest single obstacle in creating a national monument at Fort Union.

For several weeks Tolson and Wheeler exchanged letters concerning minor points of disagreement on the entrance road. Both of them agreed to send another boundary survey team to the site. The news of the successful preliminary negotiations with the Union Land and Grazing Company quickly spread in the New Mexico press. On June 1, 1939, Governor John E. Miles of New Mexico wrote to Regional Director Tolson, expressing his hope that the National Park Service would "do everything within its power to expedite the establishment of the Fort Union National Monument." [18]

The Region Three Office in Santa Fe attempted to speed up the process for the establishment of the Fort Union National Monument. In a memorandum of June 8, Arthur E. Demaray, acting director of the National Park Service, told Tolson that the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments had "not as yet classified this area as of national significance." [19] In answer to Demaray's memorandum, Tolson wrote back, "it is urgently recommended that...it be submitted for classification and approval for establishment as a national monument at the Advisory Board's next meeting." [20] Meanwhile, Tolson asked Richey to do another survey of the proposed boundaries and the road. On June 8 and 27, Richey and his assistant made separate trips to Fort Union. They discussed various details of the proposed area with Wheeler: the right-way and scenic easements. [21] In July 1939, Tolson submitted to Washington a special report, in which he recommended that the federal government establish Fort Union National Monument by presidential proclamation. Convinced of the efficacy of New Deal legislation, he also thought to set up a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at the site "to preserve and develop the site adequately." [22]

The plan to establish Fort Union National Monument, therefore, was progressing well in the first few months. At the same time that Edward Wheeler presented his case to the board of directors of the Union Land and Grazing Company, the Park Service submitted its proposal for a national monument at Fort Union to the Department of the Interior, with recommendation that it be submitted to the Bureau of the Budget and the President. Almost without delay, the Department of the Interior agreed to the proposal. By early fall of 1939, the administrators of the Park Service were so confident that Fort Union would be a national monument that they had already sent out copies of the draft form of the proclamation, even before securing title to the land. [22]

Just as the Park Service was preparing to celebrate its victory, unpleasant news arrived from New Mexico. On November 19, 1939, Wheeler sent Governor Miles a telegram saying, "Fort Union National Monument proposal encountered legal obstacle yesterday in Washington." [24] The U.S. Government wanted to omit the reversionary clause from the deed. According to the reversionary clause, the government would revert title to the company if the donated land remained "inactive." The federal government believed that such a guarantee was unnecessary even though the Union Land and Grazing Company insisted on it. Negotiations between the government and the company deadlocked.

Nevertheless, the Region Three Office of the Park Service reopened the dialogue with a new proposal. In December 1939, Tolson suggested that Fort Union be developed as a Public Works Administration project. Wheeler felt that this action would be a sufficient guarantee to satisfy the company. [25] On January 15, 1940, E. K. Burlew, acting secretary of the interior, wrote to President Roosevelt and John M. Carmody, administrator of the Federal Works Agency, asking for an allocation of $98,000 to establish Fort Union National Monument under the supervision of WPA. [26] Of the $98,000 of Public Works Funds, $13,500 would be used to acquire 837.367 acres of land for the monument, and $84,500 for improvements. [27] Unfortunately, the Public Works Administration could not allot $98,000 for the project due to limited funds. Later, the Bureau of the Budget asked the Park Service to submit an annual budget of $12,000 for Fort Union. In July 1940, President Roosevelt gave his approval to proceed in acquiring the site for a national monument, provided that the maintenance costs would not exceed the fees collected from the public. [28]

The president's approval made it possible for the Park Service to begin a new deal with the Union Land and Grazing Company. Later that July, Tolson, then acting associate director of the National Park Service, wrote to Andrew Marshall, attorney for the company, to schedule a conference working out the details of the title transaction. The representatives of both sides met on October 28, 1940. [29] Since Andrew Marshall had advised the board of directors of the company not to transfer title of the land to the government unless the deed of transfer contained a reversionary clause, the representatives of the company were unwilling to give in on this point. [30] Marshall explained that because the site lay practically in the middle of the company's holdings, acquisition of this site by a third party would create an intolerable situation. On the other side, the government negotiators argued that the provisions of the Antiquities Act of 1906 were not broad enough to permit the U.S. government to accept less than fee simple title to land transferred to it for national monument purpose. [31] But the government pointed out that it could accept the title with a reversionary clause under the Historic Sites Act of 1935, which assigned broad powers and duties to the Park Service. Marshall was interested in this idea; however, the conference did not reach any agreement.

The Park Service then decided to draft a new deed for the establishment of Fort Union National Historic Site under the Historic Sites Act of 1935. Its hope soon died when Tolson received a letter from Wheeler. On February 19, 1941, Wheeler wrote to Tolson, quoting Marshall, "there are so many pressing things to be done in connection with Mrs. Ames' estate, and there is so little enthusiasm in the family about making this gift to the government, that the matter has had to be postponed somewhat to await the doing of more important things." [32] Similarly, the nation was concerned with more important issues surrounding the Second World War. Thus, the movement to establish a national monument at Fort Union was again interrupted for a few years.

After World War II, people in New Mexico revived the campaign to create the Fort Union National Monument. New Mexicans had learned that the previous efforts failed because of the lack of local interest in the project. This time local citizens and interest groups decided to lead the movement to ultimate success. At a Masonic Lodge meeting in Las Vegas in 1946, William Stapp read a paper entitled "Chapman Lodge No. 2, A.F. & A.M.," in which he again asked his brothers to pay attention to the significance of Fort Union. [33] The paper also brought back memories of their 1929 campaign to preserve the fort.

|

|

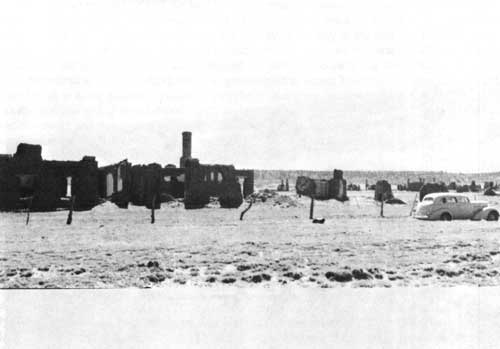

Figure 7. Fort Union Hospital in 1939. A visitor's car parked

nearby. Courtesy of Fort Union National Monument. |

One incident finally started a widespread movement for the establishment of Fort Union National Monument. On June 17, 1949, E. N. Thwaites of a Las Vegas radio station called a local resident (Mr. Walter), indicating that on June 20, the Union Land and Grazing Company was going to raze Fort Union. Quickly passing among local citizens, this news prompted Boaz Long, director of the Museum of New Mexico, and his wife to inspect the ruins the next day. They did not find anything unusual except some tourists' cars struggling to get through the muddy route. Once back in town, Long made half a dozen calls without getting any worthwhile information. [34] On June 19 Long repeated the process with no luck. Other people spent the day in search of Roger Reed, who had received a contract from the company to backfill all cisterns and wells in order to prevent people and cows from falling into them. When they finally found him, they asked him to suspend action until the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce met on June 20. Although no record showed Reed's response, the action did take place. Louis Timm, Reed's employee at the time, later recalled that he and other workers filled in all cisterns and wells, and toppled the weak walls and twenty chimneys. [35] Outraged by this action, people in Las Vegas saw the urgency of preserving the ruins of Fort Union.

With a strong will to save the historic site as well as ranching interests, local citizens took the issue to the Las Vegas-San Miguel Chamber of Commerce. On June 20, 1949, board members of the Chamber of Commerce, in regular session, voted to seek aid from the federal government and the state of New Mexico. They also voted to pay the cost of purchasing iron gratings to cover open wells and cisterns on the land. The next day their decision made headline news in the Las Vegas Daily Optic. [36] With a copy of the paper in hand, Lewis F. Schiele, secretary of the Chamber of Commerce, lost no time in writing Clinton P. Anderson, U.S. senator from New Mexico, explaining the current situation of Fort Union and expressing his concern over past destruction. Schiele urged the senator to take steps necessary to encourage the government to acquire the site. [37] E. N. Thwaites, newly elected chairman of the Fort Union National Monument Committee, took the opportunity on June 22 to write Andrew Marshall, treasurer of the Union Land and Grazing Company, telling him that the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, the New Mexico Historical Society, and the Order of Masons were interested in preserving Fort Union as a historic site. Thwaites wanted Marshall to cooperate with local groups and hoped the company would participate in a new round of negotiations. [38] The actions taken by the Chamber of Commerce, which headed this committee, began a renewed campaign.

Sending a copy of Schiele's letter to the director of the National Park Service, Senator Anderson invited the Park Service to cooperate with the local campaigners. The Park Service's response was quick, enthusiastic, and favorable. Washington asked the Region Three Office to review its files on the project and to arrange a meeting with representatives of the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce. In compliance with this request from Washington, regional director M. R. Tillotson assigned the task to Dr. Erik K. Reed and Milton J. McColm. They went to Las Vegas to discuss the current situation with Schiele. From him they learned that Roger Reed, local manager for the company, was antagonistic toward any idea that would open Fort Union to the public. On August 17, 1949, they visited the ruins and found that "considerable further deterioration had occurred since 1939-40." [39] In the report Erik Reed and Milton McColm concluded, "the situation is evidently hopeless...." [40]

The situation back east was not much better. While Thwaites was waiting for Andrew Marshall's reply to his letter, U.S. Rep. Antonio M. Fernandez of New Mexico informed him about Marshall's tactics in Washington. Fernandez revealed that although Marshall had not written to Thwaites, he had written to fellow congressmen from his home state of Massachusetts, asking them to oppose any effort to create a national monument at Fort Union. [41] At this point Marshall and his company had the upper hand.

Despite these unfavorable events, New Mexicans continued fighting for their cause. In 1949 the Masonic lodges of Las Vegas and Wagon Mound held their annual meetings at Fort Union for the first time since it closed in 1891. This initiated an annual pilgrimage to the fort. The largest one was in September 1951 when the Masons celebrated the 100th anniversary of the founding of Fort Union. More than three hundred people toured the ruins of the fort and enjoyed a barbecue. [42] "This celebration," Preston P. Patraw, acting regional director of Region Three, commented, "gave evidence of deep local interest in and support for the Fort Union National Monument project." [43]

During the same period, from 1949 to 1951, some people pushed for a state monument at Fort Union. Boaz Long first sold his idea to the New Mexico State Tourist Bureau, thinking the state could expropriate the site at a cost of $12,000. [44] He received support from both local citizens and the Tourist Bureau. By 1951 the movement for the preservation of Fort Union had gained solid ground in the state.

On August 13, 1951, more than 21 years after the first legislative attempt to make Fort Union a national monument, U.S. Rep. John J. Dempsey of New Mexico introduced a new bill (H.R. 5139) in the 82nd Congress to authorize the establishment of Fort Union National Monument. [45] The Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs of the House of Representatives asked the secretary of the interior for his opinion. On August 30, Secretary Oscar L. Chapman, in his letter to the committee chairman John R. Murdock, recommended that the bill be enacted immediately. The hearings were held on May 29, 1952. At this time objection to the proposed legislation came from the owners of the Union Land and Grazing Company, who lobbied to block the bill. Influenced by Andrew Marshall, the committee felt that "action should be delayed until full consideration could be given to certain safeguards the owners desired." [46] Like the previous legislation, the bill died in committee.

On the home front, New Mexicans constantly pressured the Union Land and Grazing Company. Lincoln O'Brien, president of New Mexico Newspapers, Inc., bragged he could influence Marshall, now treasurer of the company, because he was a personal friend. After a few letters to Marshall, it appeared that O'Brien was as good as his word. On October 12, 1951, Marshall made a visit to New Mexico. Following an aerial survey of Fort Union, O'Brien flew Marshall to Santa Fe, where they met with Preston Patraw, acting regional director, Hugh M. Miller, assistant regional director, and Erik Reed, regional archeologist and historian. [47] At the meeting Marshall told them that "the Union Land and Grazing Company did not want to appear uncooperative or obstructive...." [48] The company was concerned that "a road-way would seriously interfere with the circulation of the range cattle and an influx of careless tourist would greatly increase the hazard of grass fires." [49] Although Marshall came to Las Vegas to meet with the representatives of the Park Service in February 1952, he remained unmoved in his opposition. For a year negotiations over the Fort Union project stalled.

A breakthrough finally occurred in Santa Fe in 1953. State Senator Gordon Melody of Las Vegas helped to sponsor a bill in the state legislature. According to House Bill No. 297, the state of New Mexico would authorize the state park commission to acquire the Fort Union Military Reservation and the right-of-way for access through eminent domain proceedings. Then New Mexico would convey them to the federal government for national monument purposes. [50] On March 20, 1953, the state legislature passed the bill. Governor Edwin Mechem signed the bill on the following day.

When the state of New Mexico showed that it could acquire the land without approval from the company, the passage of House Bill No. 297 conceivably changed the attitude of Andrew Marshall and the company from one of antagonism to cooperation. As soon as the bill became law, The Las Vegas-San Miguel Chamber of Commerce planned to negotiate with the Union Land and Grazing Company to acquire lands for the proposed monument by appointing two committees: a negotiating committee and a financing committee. In less than a month the board of directors of the company, who believed the establishment of Fort Union National Monument was inevitable, decided to "deal amicably" with the representatives of the chamber of commerce. They sent Marshall to New Mexico to negotiate. Once in Las Vegas on May 6, Marshall frankly informed Assistant Director Hugh M. Miller of the Park Service, "they would not again exert pressure to defeat in Congress a bill authorizing the creation of Fort Union National Monument...." [51] In the next few months negotiations between Marshall and Schiele seemed cordial. Marshall again raised the issue of the reversionary clause and mineral rights because the company worried about the possibility of draining oil out from under its adjacent property. [52] But the company's fears imposed no serious threat at the bargaining table. By late August the two sides reached a tentative agreement that, after local donors paid the company a sum of $20,000 for "damages," the company would then transfer the lands directly for national monument purposes. [53]

In 1953 New Mexicans made their third legislative attempt in Congress to create Fort Union National Monument. Realizing the significant change through the new state law and in the attitude of the company, Rep. John Dempsey again introduced bill (H.R. 1005) authorizing the establishment of Fort Union National Monument in the 83rd Congress. [54] To accompany Dempsey's bill, Sen. Clinton P. Anderson of New Mexico submitted a bill (S. 2873) in the Senate. With the absence of negative lobbying from the Union Land and Grazing Company, the bills received a warm reception on Capitol Hill. Meanwhile people in the executive branch showed their support, recommending the bills be enacted immediately. On February 19, 1954, the House Subcommittee on Public Lands held hearings on H.R. 1005. John Dempsey and Conrad L. Wirth, director of the National Park Service, testified before the committee. Both of them did a superb job in convincing the committee that the future operation of the monument would not be too costly. In the end, the members of the subcommittee unanimously approved the bill and sent it to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. [55]

Accompanied by a reversionary clause, which was acceptable to the Department of the Interior, H.R. 1005 encountered little opposition from the committee and passed the House in late March. Immediately, Senator Anderson urged the Senate Subcommittee on Public Lands to support his monument bill (S. 2873) and to hold a hearing, which, he thought, needed only a few minutes. [56] During the era of the Second Red Scare, the McCarthy hearings had preoccupied the Senate Chamber in which many members "engaged in that circus everyday." Twice, Henry C. Dworshak, chairman of the Subcommittee, tried to set up the hearings on the bill and each time a scheduled hearing had to be canceled due to certain "difficulties." Finally, Anderson requested that the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs report the bill out without subcommittee's consideration. The full committee did so and sent the bill to the floor. [57] On June 15, 1954, the bill passed the Senate and went to the White House. On June 28, 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed it. The new law authorized the secretary of the interior to acquire the site and remaining structures of Fort Union for national monument purposes. [58]

Along with this long and troublesome legislative battle in Washington, the main campaign for the establishment of Fort Union National Monument was taking place in New Mexico. After the preliminary agreement between the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce and the Union Land and Grazing Company, the finance committee superseded the negotiation committee in taking a major role in the business. The finance committee was responsible for raising the $20,000 required under the agreement. In late 1953, those involved realized that a larger, independent organization was needed to handle contributions. Thus, a non-profit organization known as Fort Union, Inc., was formed to replace the finance committee in December 1953. The specific purpose of the new organization was to undertake the acquisition of the site of Fort Union through fund raising. [59] Recruiting interested citizens from different groups such as politicians, businessmen, teachers, and Masons, Fort Union, Inc., united all forces in the campaign in a coordinated way.

At the first meeting, on January 11, 1954, eleven of the original fourteen members of Fort Union, Inc. elected Ross E. Thompson as president, James W. Arrott vice-president, and Lewis F. Schiele secretary-treasurer. [60] Under the leadership of these three able and devoted men, the corporation launched a state-wide campaign to secure $20,000 to reimburse the Union Land and Grazing Company for their inconvenience. Since the proposed road to Fort Union had been approved as a secondary federal aid project, the New Mexico State Highway Department agreed to contribute matching funds of $10,000. Through its coordinators in Las Vegas, Raton, Gallup, Deming, Santa Fe, Socorro, Albuquerque, Roswell, and Farmington, Fort Union, Inc., contacted various companies, organizations, and individuals who might be interested in helping the cause. [61] Fund-raising efforts were also taken to the public schools. No contribution was too small to be accepted. For example, Castle Junior High School of Las Vegas in a poster stated that even a five-cent contribution would be welcome. [62] Each student who contributed would receive a small card saying, "I helped save Old Fort Union." By the end of 1954 the organization had already collected $10,076 after spending only $431.14 on office supplies; it had a net deposit of $9,645.61. [63]

In the meantime, federal and state government politicians continued to work out the details for land title and the access road. The chief concerns of the company were the scenic easement and the cattle underpasses. According to the agreement, the government was going to build at least three underpasses on the highway and prohibit all billboards along the road. On June 10, 1955, Regional Director Hugh Miller sent a draft of the deed to Andrew Marshall and the attorney general of the United States. Six days later the board of directors of the Union Land and Grazing Company voted to grant 720.6 acres of land to the U.S. government. The final deal came on August 24, 1955, when Ross E. Thompson, on behalf of Fort Union, Inc., turned over to Marshall two checks totaling $10,000. On the following day the deed was recorded with the County Clerk of Mora County. With the approval of the attorney general, the U.S. government accepted the donation on October 18, 1955. On April 4, 1956, Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay signed the order to establish the Fort Union National Monument in Mora County, New Mexico. [64] The ruins of Fort Union officially became a national monument.

After the nation bid farewell to the frontier in 1890, the War Department abandoned Fort Union, once the largest military post in the West. The land reverted to the original owners; the adobes reverted to the earth. In the next 65 years the buildings at the fort gradually deteriorated because of natural attrition and human vandalism. Many people, however, were concerned with saving the old fort from further destruction and asked for help from the federal government and the state of New Mexico. From the 1920s, New Mexicans, joined by government officials, campaigned to created a national monument at the site. In 1956, after many defeats, they finally achieved their goal. The establishment of Fort Union National Monument was the result of an arduous and persistent effort by both the officials of the National Park Service and the citizens of New Mexico.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foun/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2001