|

Fort Union

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 3: REHABILITATING AND PRESERVING THE FORT

|

|

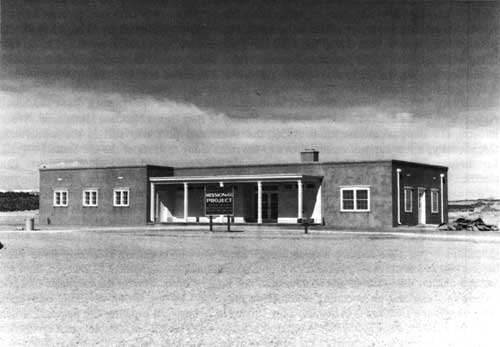

Figure 8. In April 1959, the permanent visitor center was to be

completed. The sign in front of the building again indicated that the

MISSION 66 program played a significant role in the development of Fort

Union National Monument. Courtesy of Fort Union National Monument. |

The rehabilitation and preservation of the ruins of Fort Union have been extremely difficult tasks. Unlike the stirring campaign to secure the legal title to the land, the tedious daily routines to keep the ruins in optimum condition for the public have required more effort and resources. After acquiring Fort Union in 1956, the National Park Service promptly developed it into an active national monument to greet interested visitors. Since then the Park Service Southwest Regional Office has devoted a considerable amount of money and manpower to the preservation of the remaining structures in order to keep deterioration to a minimum. As a faithful caretaker for 36 years, the National Park Service has done an admirable job in rehabilitating and preserving the historic site of Fort Union.

A few months before Fort Union joined the national park system, the Region Three Office (the present day Southwest Regional Office) had already started the development of the proposed national monument. On December 6, 1955, Kittridge A. Wing of Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico took up residence in Las Vegas as a Park Service representative. From there he personally supervised the construction of the entrance road, which was the first project at the monument. Twelve days later, he accepted appointment as acting superintendent of Fort Union National Monument and converted his rented residence into a temporary office. [1] At the end of 1955, Floyd Haake Construction Company of Albuquerque began to build a 7.6-mile road from U.S. Highway 85 to the fort. [2] Because of "perfect weather conditions," the construction progressed rapidly. By March 1956, the two-lane road across the prairie, with a concrete bridge over Wolf Creek and two cattle underpasses, was ready for surfacing. It took several more months to complete the paving. The Park Service accepted the road in early June.

While the new road was traversing on the prairie toward Fort Union, administrators at the regional office in Santa Fe labored at their plans for the physical development of the monument. A few of the major issues were the placement of buildings and utilities, the layout of trails, and the stabilization of the ruins. The Park Service first contrived to erect living quarters. On March 1, 1956, the fort received two house trailers from the Public Housing Administration of Piketon, Ohio. Before the Mora Electrical Cooperative extended service to the fort, Wing arranged to temporarily connect the trailers to utility lines at the nearby Needham Ranch owned by the Union Land and Grazing Company. [3] On May 5, he moved from Las Vegas and occupied one of the trailers at the fort. For the first time, the Park Service had a representative living close enough to monitor the fort daily. During that same month, Fort Union also obtained a 16'x20' wooden cabin from Los Alamos to serve as the temporary office and visitor center. [4]

In addition, Wing brought Clifford W. Mills, a seasonal ranger, from Los Alamos to assist him. The two immediately began work on a tentative visitor trail, which they finished within a month. Although Fort Union now had a visitor center, an interpretive trail, and living quarters, all of them were temporary. The physical development of the monument was just beginning.

Despite the few service facilities available at Fort Union, the Park Service was anxious to open the site to the public. On June 8, 1956, after two months of careful planning by Wing and Ross Thompson, the monument held a ribbon-cutting ceremony. In the morning, a sixty-piece band from New Mexico Highlands University in Las Vegas welcomed more than six hundred people. A rostrum and red ribbon straddled the new road about a mile southwest of the fort. Cutting the ribbon with a nineteenth-century cavalry saber donated by Harry and Sam Wells, Governor John F. Simms officially opened the monument. [5] Speakers congratulated those who had brought the plans for the establishment of the monument to a successful conclusion. After that, most of the crowd jumped into their cars and formed a motorcade of 150 vehicles behind the governor's sedan, and drove to the monument. At the end of the program, Fort Union, Inc., treated everybody to a luncheon. [6] The opening ceremony, as Wing said, began "Fort Union's new life."

In reality, Fort Union's "new life" meant a full-scale effort toward rehabilitation and development. As soon as the honeymoon was over, the monument entered the first period of intensive construction, which focused on service facilities and ruins stabilization. Preventing the entry of cattle onto the site was one of the Park Service's main concerns. On June 29, 1956, Steve Franken of Las Vegas received a contract for $5,048 to fence both parcels of the monument (the Third Fort and the Arsenal). [7] Franken completed the perimeter fencing of the Third Fort area in less than a month. In early August, he enclosed the Arsenal. The completion of the fencing marked "the final exclusion of stock and the beginning of recovery of the grasses from recent overgrazing." [8]

As a unique section of the National Park Service, Fort Union was the first monument established and developed entirely under MISSION 66. In 1956, Director Conrad L. Wirth of the National Park Service launched an ambitious conservation program to develop national parks to permit the visitors' maximum enjoyment while still pursuing the preservation of the park's scenic and historic resources. The 800-million-dollar program was schedule to end in 1966, the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the National Park Service--hence the name MISSION 66. [9]

The construction of a permanent visitor center and residential housing topped the list of the master plan of development. People had different ideas about the location and style of the proposed visitor center. Some persons suggested that one of the historic barracks should be restored and used as the visitor center. But after a few months of discussion, the Park Service adopted Wing's blueprint to build a New Mexico territorial-style visitor center south of the main ruins and in line with the old hospital. [10] The National Park Service Western Office of Design and Construction (WODC) worked out the preliminary plans of the proposed visitor center and residence houses. Just as people were ready to see the start of the construction in October, the regional directors' conference in Washington decided to withdraw the 1957 fiscal year construction funds from Fort Union, with the intention of completing most of the development in a "package" during the 1958 fiscal year. [11]

Nevertheless, some construction continued in 1957. In September, W. H. Elliot of Albuquerque received a $70,000 contract to construct two residences at the southern edge of the park near the main gate. His company completed a house and a duplex the following spring. [12] However, Acting Superintendent Wing was not able to enjoy the new living quarters. In January 1958, his wife Anna died of a heart attack. Soon after, he requested a transfer from Fort Union, where the couple had devoted a great deal of their energy to the new national monument. With sympathy for Wing's tragedy and praise for his work, the Park Service promoted him to assistant superintendent of San Juan National Historic Site in Puerto Rico. In April, Homer F. Hastings, former superintendent of Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico, arrived at Fort Union to assume his duty as superintendent. [13] He immediately took up residence in the newly constructed house.

Born at Montrose, Colorado, Hastings began his Park Service career as a seasonal ranger at Carlsbad Caverns National Park during the summer of 1930. In 1937, he became a permanent employee, working first at Aztec Ruins. Before his new appointment at Fort Union, Hastings had served as superintendent at several Park Service units in Arizona and New Mexico. The arrival of this twenty-year veteran guaranteed strong leadership for the development of Fort Union National Monument. [14]

During his administration, Wing brought archeologist George Cattanach from Montezuma Castle National Monument in Arizona and filled the historian position with Donald Mawson, a tour leader at Carlsbad Caverns National Park. Following in Hastings's steps, Cattanach and Mawson occupied the separate duplex residence.

Since no modern facility had existed in the area, the new monument had to bring in everything from the outside. The basic utilities included water, electricity, telephone lines, and a sewage system. A small spring flowing in Wolf Creek west of the Third Fort appeared to be the only surface water accessible to the monument. Sometimes the creek was bottom dry. Thus, Fort Union needed a sufficient water source. After a groundwater study in July 1956, the U.S. geological surveyors affirmed the quality and quantity of groundwater at the site. They also helped to choose a suitable location for the well the following April. The Park Service awarded Red Top Drilling Company of Las Vegas a $3,725 contract to drill for water. On August 22, 1957, the company completed a 325-foot well. [15]

Meanwhile, the Park Service gave a $29,000 contract for water and sewage systems to Starr and Cummins Company of Albuquerque. According to the deal, the company would install one 52,000-gallon water tank at the northeastern corner of the Third Fort, two 300,000-gallon sewage lagoons at the southwestern corner, and all the pipe lines. By spring of 1958 the water and sewage systems were operational. A year earlier, the Mora Electrical Cooperative had extended power lines to the monument. A modern communication system was also necessary for the monument to operate efficiently. In February 1959, after much negotiating, the Mountain Bell Telephone Company finally provided its services to the remote fort. [16]

When the package of construction funds for the 1958 fiscal year arrived, Fort Union immediately invited various business firms and individuals to bid on all the related projects. Again, Floyd Haake won a contract for $30,148 to surface an existing 1,600-foot dirt road in the residential area and to construct a new parking lot in front of the visitor center. Kueffer Construction Company of Las Vegas, another low bidder, got a $71,804 contract to build a visitor center and a utility building and to extend power lines to both buildings and a telephone line to the visitor center. [17] Close cooperation between the two companies provided a healthy working environment to guarantee that all the construction progressed speedily. On September 2, 1958, the newly surfaced residential loop road and the spacious visitor parking area passed the Park Service's inspection. Kueffer Company handed the visitor center and utility room over to Fort Union on February 17, 1959. For almost three years prior to that, the park staff had run the monument from a shabby wooden cabin, without running water or sewage lines. Visitors as well as staff had to use outdoor pit toilets. After blizzards or gales, the desks inside would be covered with either snow or dust. A reward eventually came in March 1959 when the park staff happily moved into the territorial style visitor center. [18]

|

|

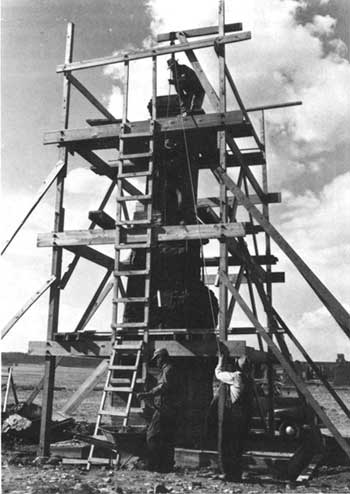

Figure 9. In late 1956, the stabilization team first worked on the

remaining chimneys. Photo shows Martin Archuleta and other unidentified

workers filling a chimney with cement. Courtesy of Fort Union National Monument. |

Along with the development of supporting facilities, the excavation and stabilization of the ruins received an equal amount of resources and energies from the Park Service. During his trip to Fort Union on December 13, 1955, archeologist Charles Steen of the Park Service realized that deterioration was taking place with astonishing speed at the ruins. Photographs taken in 1945 showed two dozen chimneys standing at full height; ten years later, only six full chimneys remained, and two of them probably would not survive another winter. [19] Steen's discovery urged the Park Service to come up with protective measures for the crumbling walls and chimneys. Accepting his suggestion, the regional office decided to start a rehabilitation program as soon as the monument was established.

On August 1, 1956, archeologist George Cattanach arrived at Fort Union to direct the stabilization and excavation of the ruins. Even though the Park Service already had accumulated much experience in the stabilization and preservation of historic structures, the adobe walls at the fort posed a new challenge. Because there was no proven method for stabilizing adobe buildings, trial and experimentation seemed to be the only satisfactory answer. Only a week after he reported for duty, Cattanach led a crew of five men to begin the emergency preservation program. Prior to this work, Acting Superintendent Wing had directed a four-man team to work on several preliminary projects such as picking up roofing tin from the grounds. This work made Cattanach's job easier. The initial objectives consisted of clearing away rubble and debris, reinforcing chimneys with concrete, and experimenting with various materials for capping the adobe walls. [20] In the first two months, excellent weather enabled the crew to complete the stabilization work on the remaining chimneys of the commanding officer's residence, and to clear the original flagstone sidewalks that totaled about 800 lineal feet in front of officer's row.

Although Cattanach and his workers accomplished the initial work, the entire program lasted less than three months. In the first two months, the stabilization crew spent $6,700 of the project's total $18,020 budget for the 1957 fiscal year. Thus, in late October, the park had to lay off four persons due to lack of funds. [21] During the winter, Cattanach and the only maintenance man excavated sections of the ruins. At the same time, he was planning a stabilization program for the next season, developing techniques, securing materials, and acquiring advice. The high winter winds continued to level the more fragile adobes. Once a six-foot block of chimney was blown down.

The stabilization work resumed in the spring of 1957. The first season provided the monument staff with much useful experience. Because the adobe walls of the forty historic buildings comprised a total length of five miles, one hundred percent preservation was impractical and too costly. Wing and Cattanach tried to define a limited objective for the project. Any building that contained more than fifty percent of original wall material would receive maximum stabilization attention. But they did not deliberately ignore the other structures because they knew that once a building was reduced to foundations alone, it became much less interesting to visitors. [22] Their strategy for priority never restrained their willingness to save as much of the ruins as possible. In May, the stabilization crew increased to seven members with directions to focus on the adobe walls. They used steel braces and cement paste to support the weakened portions of buildings. Then the workers capped the weathered walls with soil-cement bricks. Finally, the entire structure was sprayed with a silicone preservative to make it moisture resistant. However, the silicone had to be applied annually to assure maximum protection.

The stabilization proceeded smoothly. In June, the preservation team recruited three more persons. Some of them began to work on excavation tasks while the stabilization job continued throughout the ruins. Again, in October, the park laid off the full crew of ten men due to limited funds, however, they had accomplished most of their job.

The winter of 1957-58 was an extremely hard one. Covering Fort Union with eight feet of snow, the cold weather hampered all construction and stabilization projects. As in the previous winter, Cattanach stayed inside his warm residence and contrived various preservation techniques for the next spring. As soon as the snow melted into Wolf Creek, a twelve-man crew started the new working season. In May 1958, the stabilization crew was expanded to 21 persons. Their main objectives were to excavate the buildings and improve the visitor trail through the ruins. By the summer, they had excavated most of the buildings by removing thousands of cubic yards of dirt. Under Cattanach's leadership, the crew did an excellent job on excavation and stabilization. To reward his superb performance at Fort Union, the regional office promoted him to a higher position at Mesa Verde National Monument. In early September, archeologist Rex L. Wilson of Ocmulgee National Monument in Georgia came to Fort Union to replace Cattanach. [23] As another winter approached, the park staff could look back on their most successful season.

Under Wilson's direction, excavation and stabilization continued at great speed. All stabilization was undertaken on a priority basis; those walls and features in most urgent need of repair received the earliest attention. Small repair jobs in buildings often followed at a later date. [24] Before the close of 1959, people saw the success, with the realization that the stabilization of the ruins would be completed by the next season. Thereafter, a small maintenance crew could handle the daily routines of preservation. By August 1960, after spending four years and more than $100,000, the Park Service had accomplished the initial emergency stabilization. [25] The program was extended for another fiscal year for wrap-up operations.

Despite success in protecting the ruins, stabilization at Fort Union left a negative impact on the archeological deposits located in the Third Fort area. Because of little information on the archeological deposits and the pressure of time on the project, Cattanach and Wilson allowed the crew to use destructive methods. For example, a bulldozer was used extensively on the exterior of the various structures to clear deposits that had built up against the walls. These efforts, which removed dirt and debris to the wall footings or below them, also removed archeological evidence of the construction or demolition sequences of the various structures. [26]

Although rehabilitation rather than reconstruction of the fort was the substance of a Capitol Hill agreement for the establishment of Fort Union National Monument, the Park Service later modified its position. Along with the construction of supporting facilities on the outskirts of the ruins, a small reconstruction project took place. The park staff believed that if a replica of the flagpole could stand in the center of the parade ground, it would enhance the historical atmosphere of the fort. After a year of research, historian Donald Mawson produced an accurate drawing of the flagstaff. In February 1959, Kueffer Construction Company erected a replicated flagpole in front of the commanding officer's quarters. [27]

Another construction project at the ruins was a visitor trail. Designed by Wing himself, the primitive sand-gravel trail, 2,900 feet long and six feet wide, appeared in April 1957. A year later, workers added 2,500 feet of soil-cement trail. Some parts of the trail were surfaced with emulsified asphalt. In 1959, after spending $11,936, The crews at Fort Union had completed a 4,103-foot trail network. [28]

|

|

Figure 10. Carlos Lovato, Ike Trujillo, Benito Lucero, and Dionicio

Ulibarri stabilizing the wall of Commissary Warehouse, October

1958. Courtesy of Fort Union National Monument. |

Nineteen fifty-nine marked a watershed in the history of Fort Union National Monument. When it became a national monument in 1956, the abandoned post was still in the wilderness. Occasionally, a few curious visitors drove to the ruins along the ruts of the old Santa Fe Trail. Just three years later, Fort Union had a permanent visitor center and two residence houses with electricity and running water. A paved highway and telephone line had linked the fort to the rest of the world. Even the aged adobe walls had received modern cosmetic treatment such as the silicone coating. Indeed, the monument had finished its first period of intensive development and become a fully functional national monument.

Certainly, it was time to have a celebration. Since the ribbon-cutting ceremony three years before, people had constantly asked for a formal dedication of the monument. However, the Park Service did not think that it was wise to hold this kind of event without the existence of basic service facilities and an operating stabilization program. By the spring of 1959, everybody realized that the situation was mature; Fort Union, Inc., began to organize the pageant, which was scheduled for June 14, 1959. In order to bring as many people as possible, open invitations printed on placards were placed in the windows of most business firms in Las Vegas. [29] As had occurred during the campaign for the establishment of Fort Union National Monument, the dedication again showed the efforts of the community.

Around one-thirty on the afternoon of June 14, the Twelfth Air Force Band started playing while three thousand attendants took their seats between the new visitor center and the old officer's quarters. At two o'clock, four F-100 Super Sabre jets flew over Fort Union as the signal came to hoist the American flag up the replica flagpole. To give a 21-gun salute with a 105mm howitzer, 101 members from the 726th AAA Battalion of the New Mexico National Guard presented the colors. A series of speeches followed. Among the prestigious speakers were President Ross Thompson of Fort Union, Inc., Superintendent Homer Hastings, New Mexico's Lieutenant Governor Ed V. Mead, Brigadier General William C. Kingsbury of the Air Force, Assistant Secretary of the Interior Roger C. Ernst, and Director Conrad L. Wirth of the National Park Service. In his dedication address, Ernst delightedly expressed that he had the double opportunity to dedicate the fort and the visitor center. He paid tribute to those who won the frontier and those who won the monument. [30] Indeed, the ceremony formally ushered in a new era for Fort Union National Monument.

As the decade of the 1960s arrived, the administration of Fort Union properly shifted its emphasis of management from construction to maintenance. Routine operations such as cleaning the water tank, painting the wooden fences, and repairing the visitor center filled the park staff's many working hours. In 1963, funds available at the regional office permitted the addition of another residence at the monument. Cillessen Brothers Company of Albuquerque completed construction during the next spring. [31] Except for this small expansion, no major construction occurred at the place during the early 1960s. Most workers just kept themselves busy with daily maintenance.

Ruins preservation continued. The maintenance crew applied silicone coating to the walls that needed it twice a year. In 1963, however, the collapse of several walls due to high winds renewed the search for more reliable methods of stabilization and preservation. The workers tried a new technique that used Redi bolts and guy cables to strengthen those walls in the greatest danger of collapse. By September 1965, all the adobe walls at the fort had received a silicone coating with the exception of one section of the Post Hospital's wall, which was being tested with sandstone, adobe paste, and epoxy resin. It proved that these new methods were better. [32]

From the mid-1960s, Fort Union National Monument began to try other new ways of preserving the ruins on a large scale. Previously, workers routinely applied silicone coating to the crumbling adobe walls to prevent them from further deterioration. Although silicone temporarily worked as a shield to fend off the sun, snow, and rains, in fact, silicone coating often trapped moisture inside the structures and weakened the entire building. White silicone coating, which reflected more light, destroyed the unique complexion of the ruins, which resembled the reddish color of the soil. Cooperating with the Park Service and the University of Arizona, the Globe Archeological and Stabilization Center in Arizona gradually developed a new technique to preserve the adobe structures. Specialists at the center recommended that Fort Union try epoxy resin and adobe paste on the ruins because they were closer to the original materials. Under the direction of the center, the monument underwent large scale experimentation. [33]

As devoted caretakers of the ruins for ten years, Fort Union's staff won their reputation in the National Park service. In July 1965, three regional offices of the National Park Service (the Southwest, Southeast, and Midwest) formed a joint committee to undertake a survey of seven western forts. [34] Fort Union's management was deemed the best among all seven western forts, and the committee suggested that the other forts learn from Fort Union's experience. "Fort Union, New Mexico," concluded the committee, "was an outstanding example of good management." [35]

One of the chief caretaking operations in the late 1960s was to reconstruct the visitor trail. When the monument opened to the public, the original flagstone walks built around 1877 were repaired to serve as a part of the visitor route. The larger portion of the route was a 4,000-foot path of emulsified asphalt laid in the late 1950s. After ten years, this weather-beaten path started to crack. Because the heat and moisture trapped by asphalt made the trail an increasingly fertile breeding ground for undesirable vegetation, rapid growth of weeds constantly broke the surface of the asphalt path from below. By 1967, Fort Union administrators had to consider the reconstruction of the trail, writing a tentative proposal for a $19,000 project. [36] Awarded the contract, Howard Flanagan of Las Vegas, in the spring of 1968, began to replace some sections of the asphalt trail with flagstones. Before the winter came, he finished approximately 1,700 feet of flagstone walkway. [37]

Extensive repairs of the visitor trail continued in the 1970s. Superintendent Claude Fernandez reported in 1972 that more than 13,000 square feet of the asphalt trail needed either replacing or repairing. Because of the unavailability of local gravel and a considerable amount of money, the park had to postpone the work for three years. In 1975, the regional office appropriated extra funds for the project. Then the monument replaced the remainder of the asphalt path with a rock-crusher waste walkway. [38]

In addition to the new visitor trail, a series of construction projects occurred at Fort Union in the first half of the 1970s. Expecting to provide better service to the public, park staff installed several picnic tables outside the visitor center and interpretive-resting benches along the visitor trail. For its own benefit, the monument acquired two storage buildings for stabilization equipment, general supplies, and maintenance tools. Moreover, all the service buildings, including the visitor center, living quarters, and maintenance shop, received a facelift. In 1973, Superintendent Ross Hopkins reported that all the service buildings were in "a sad stage of deterioration." They needed to be repaired immediately. Carefully assessing the conditions of the structures, the park began to repair them the following spring. That summer, a heavy thunderstorm, which covered the ground with hail up to eight inches deep, caused $4,000 in damages to vehicles and buildings. But the storm did not stop this project. By the end of 1974, all the buildings were rehabilitated. [39]

During the same period, personnel changes occurred at Fort Union. In January 1971, Superintendent Hastings retired after almost 13 years of service at the monument. Although in the last few years of his tenure he became less energetic and creative, everyone felt that Hastings's leaving was a big loss to the park. He not only held the longest tenure as superintendent in the history of Fort Union National Monument, but also acted as superb leader in the early development of the park. In April, Claude Fernandez of Carlsbad Caverns National Park came to fill the vacant position. He remained at the fort for only 26 months, during which severe diabetes limited his performance. In June 1973, he accepted a new job as supervisory park ranger at Chamizal National Memorial in El Paso. Again, Fort Union was looking for a new, energetic, and healthy leader. Fortunately, a month later, Ross Hopkins, a 15-year Park Service veteran came from the Denver Service Center of the Park Service and began his seven-year administration. [40]

As soon as he arrived at the fort, Hopkins injected new energy into the never-ending task of adobe preservation. Although maintenance routines such as filling cracks with soil-cement bricks and capping walls with adobe mortar proceeded as usual, the preservation crew developed a new system to take care of the ruins. Besides emergency repairs following unpredictable severe weather, a regular five-year maintenance schedule was assigned to each wall section because erosion usually began to occur within a five-year period. Designed to beat mother nature, this system made the preservation crew operate more efficiently. Original wood beams were treated with wood preservative, and metal was painted with rust resistant paint on a five-year cycle.

When a spot check of the ruins using photos from the stabilization records showed most of the adobe walls firm and strong, the keen workers found that the stone foundations, which were not included in the routine maintenance process, were in increasingly bad shape. They needed a complete resetting and pointing. [41] The Park Service decided to use the skills and experience of some Indians who were experts in stone building. In the fall of 1973, archeologist George Chambers from the Arizona Archeological Center, with a special grant of $25,000, directed a ruins stabilization unit of Navajos to ameliorate the damage to the stone foundations. During the eight-week project, they focused on the officers' quarters and reset all the limestone foundations. The chosen sections were reinforced with cement. The Navajos did an excellent job. [42]

Beginning in the second half of the 1970s, the ruins entered another intensive care period. In 1976, Hopkins helped acquire special funds--$75,000 annually--for a five-year stabilization project. At the same time, the Division of Cultural Resources of the Regional Office provided the monument with a weather station, set up near the Sutler's store, to monitor weather affecting the ruins. [43] With the new funding, equipment, and enthusiasm, employees at Fort Union immediately started their work on stabilizing the ruins. Before winter arrived, they had complete basic training in masonry repair and a drain system for the foundations of some buildings. Because of this project, the monument kept a stable team of ten men to labor on the ruins from each spring through fall during the next five working seasons.

As usual, Fort Union established its goals each year. Cyclical maintenance and improvement of park facilities were the major objectives for 1977. The asphalt trail and flagstone walkways were repaired. Workers assisted the Division of Cultural Resources in photographing, measuring, and inventorying all Third Fort buildings for a historic structure report. In the following summer, maintenance personnel again replaced some parts of the stone walkway laid only a decade ago. In general, the maintenance operation went smoothly.

Nevertheless, mother nature caused more troubles for the ruins. As the result of heavy snow and winds in February 1979 and January 1980, several huge sections of the adobe walls collapsed. Thus, during these two seasons, emergency stabilization was the primary issue. [44] After receiving an additional $83,000 for this urgent need, the preservation workers re-treated all the walls of the Third Fort and Arsenal with adobe coating and metal supporters. By the fall of 1980, the crew members had completed the stabilization of the building foundations for all the post officers' quarters and half of the depot officers' quarters. [45] Most of the five-year emergency preservation plan was achieved.

In July 1980, just as it celebrated its twenty-fourth birthday, Fort Union National Monument underwent a major administrative change. With a strong desire to reduce administrative costs and inefficiency, Southwest Regional Director Robert Kerr combined the administration of Fort Union and Capulin Mountain under Capulin's superintendent, Clark D. Crane. [46] When Ross Hopkins left for Saguaro National Monument in Arizona on July 27, a unit manager position replaced the superintendency at the fort. Until the selection of a permanent manager, general foreman Willis E. Reynolds served as acting unit manager. In late December, the Regional Office offered the new position to Carol M. Kruse of Canaveral National Seashore in Florida. She reported for duty on January 6, 1981. Despite minor adjustments in operating procedures, the new organization made a smooth transition. [47]

Although Fort Union lost its sovereignty, daily business was as usual, and was perhaps even more efficient. Under the benevolent rule of the superintendent of the Capulin Mountain National Monument, all division chiefs at Fort Union were responsible for their own day-to-day operation. They looked to Capulin counterparts only for special expertise or the coordination of projects that affected both areas. However, Crane separated the maintenance functions from those of the preservation team by creating two distinct divisions: maintenance and preservation. Each had its own specific agenda. Consequently, this realignment resulted in a more productive operation for both divisions.

Besides this administrative reorganization concerning the maintenance of the fort, the strategies and tactics for ruins preservation took a novel departure from their traditional course. Since the establishment of the monument, workers had been using soil-cement bricks and silicone coating as the main materials to stabilize the crumbling structures. Later, it proved that both materials trapped moisture inside the walls and hastened their deterioration. From the 1960s, the park staff started to test some new material and techniques but they were never applied on a large scale. In the spring of 1981, prior to the new working season, Fort Union, with the assistance of regional architect Dave Battle, devised a comprehensive plan for ruins preservation. According to the plan, first the fort's workers would return to the use of original materials rather than the cement and chemical products in adobe and foundation work. Second, the preservation crew would concentrate on repairing the ruins whose condition constituted major safety hazards to employees or visitors. Finally, the monument would immediately reinforce the foundations where the identity of entire buildings or of remaining walls was about to be lost. These three points began to serve as the park's principles for future ruins rehabilitation. [48]

Undoubtedly, the preservation activities were better prepared and executed in the following years. The severe rains and storms in the summer of 1981 once more indicated that the traditional cement-base protective plaster proved unsatisfactory when it cracked and peeled off from the walls. This situation gave more opportunities for experimenting with new methods on a large scale. The crew patched the damaged and exposed adobe structures with an adobe paste, which consisted mainly of sand and clay. For the first time, the entire project was photographically documented, both before and after. [49] The photographs provided more accurate data for future care of the ruins. In 1984, the monument purchased a new 35mm Olympus camera to facilitate high quality photographs for the ruins preservation work. Today, Fort Union has a complete set of photo files of the ruins.

Through the mid-1980s, the preservation crew continued to try various new methods and techniques. A protective coating was applied to the exposed adobe surfaces when the multiple layers of cement plaster began to crumble away. The mud coating appeared capable of surviving longer than the other materials did. Another new method was to make a large number of adobe bricks at the beginning of each working season to allow adequate drying time before use. This increased the life span of bricks. Moreover, workers realized that it was necessary to clear debris and weeds from the base of all structures for the purpose to minimize moisture penetration. From 1982 to 1986, the preservation crew devoted many hours to such activities as removing rubble from fallen walls, resetting rocks to original locations, and uprooting weeds around building foundations. These operations provided better care to the ruins in general. [50]

A systematic study of adobe structures is as important as preservation itself. Before Fort Union outlined an appropriate preservation plan, some basic information about these historic structures became crucial. From the late 1970s, the monument, with the help of the Regional Office, started to gather accurate data about the ruins. They included historical research and current surveys. In 1982, Dwight Pitcaithley of the Regional Office and Jerome Greene of the Denver Service Center completed a long-term project, "The Historic Structure Report, Historic Data Section, the Third Fort Union, 1863-1891," which provided an excellent data base for Third Fort buildings. [51]

Meanwhile, Fort Union obtained information pertaining to the fort and related historic structures from the State Historic Preservation Office because New Mexico had excellent records about historic adobe buildings. [52] The park staff also accumulated more data by surveying all the ruins. As a result of the studies conducted in 1984, the monument had a better idea about its assets. For example, surveys showed that the Third Fort, Sutler's store, and the Arsenal contained 18,072 linear feet of foundations and 125,336 square feet of adobe surface suited for preservation work. [53] The collection of information paved the way for future research and rehabilitation.

All non-historic buildings at the fort also underwent change. In 1982, the monument began to renovate the out-of-date visitor center by relocating the interior partitions, insulating the walls, carpeting the lobby, and installing florescent lights. Renovations included the reconstruction of two restrooms to provide easy access for handicapped visitors. When the remodeling of the visitor center was completed the following spring, it resulted in a more pleasant environment for both visitors and employees. [54] As had the visitor center, the residential houses and maintenance shop received new foam roofs and stucco paint. However, a severe thunderstorm in the summer of 1983 struck Fort Union. Concentrated in the residential and maintenance areas, the thunderstorm, combined with a 37 mile-per-hour wind, caused approximately $30,000 in damages, which included the destruction of a storage shed and damage to the new roofs. This was the most costly natural disaster in the history of the monument. [55] But maintenance workers soon repaired most of the damaged buildings. In 1984, Fort Union concluded its four-year reroofing project.

Another aspect of this fresh outlook at the fort was a new trail and roads. In July 1983, as a service project, the Boy Scout troops of Las Vegas laid out a flagstone walkway from the visitor center to the hospital. Additionally, the Boy Scout troop from Santa Fe erected three platforms along the trail for interpretive purposes. [56] In 1984, under the Federal Lands Highway Program, Fort Union received $200,000 to reconstruct its aged roads. Awarded this contract, R. L. Stacey Construction of Santa Fe began to reconstruct and resurface all the blacktop roads within the park boundary. The company repaved all the residential driveways, the entrance road, and the maintenance parking area. They finished most of the job in December 1985. [57] After the Park Service found some minor defects, the company returned the next summer to put new patches and fog coats on some cracked areas. [58] By 1986, Fort Union had renovated almost all its supporting facilities and become a more accessible and accommodating place.

In March 1987, Carol Kruse accepted a promotion to superintendent of Tonto National Monument in Arizona. The fort lost a good manager. Nevertheless, two months later, exciting news arrived that the new regional director, John E. Cook, had decided to grant Fort Union independence from Capulin Mountain National Monument. Realizing that Fort Union and Capulin Mountain had represented totally different values and purposes, he dissolved the seven-year odd marriage between the two units. Although the separation cost a little money, it helped the development of Fort Union, which gained more budgetary freedom. [59]

Between June 7 and October 1, the administrative functions at the two sections were gradually separated. During that time, Douglas C. McChristian of Hubbell Trading Post in Arizona came to assume the superintendency of the fort. As an energetic manager, he helped carry out a smooth transition of the administration. Accordingly his administration placed emphasis on finding more efficient methods of ruins preservation. His tenure, however, lasted less than a year. In May 1988, John Cook called him to Santa Fe for a new appointment. Later, he was selected as historian of Custer Battlefield National Monument (the present day Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument) in Montana. Several months had passed before the monument got a new chief. On August 15, Harry Myers, a seven-year veteran as superintendent of Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial in Ohio, came to fill the same position at Fort Union. The arrival of Myers, an experienced leader who fully understood how to build relationships among and with employees, opened a new chapter in the administrative history of the monument. [60]

After Fort Union became a separate administrative unit, it immediately entered a new era of ruins preservation. Managers and workers were deeply involved in more comprehensive research and planning instead of simple practice. Until that time, the fort lacked enough information for the proper management of its cultural resources. Although Greene and Pitcaithley had produced a historic structure report, the study contained virtually no information on the First and Second Forts. The park even lacked a historical base map of the ruins. In 1989, regional historian Melody Webb initiated a new project for the creation of the historical base maps of Fort Union. Research historian James E. Ivey received the assignment. His work will soon be completed. [61]

In 1987, the Regional Office and Fort Union began to conduct a thorough investigation of the remaining structures. Their purpose was to collect all the data concerning the ruins and develop a comprehensive preservation plan. Approving $12,000 for a preservation-plan study, the regional office asked research historian Rick Geiser to do some preliminary work on the subject. [62] A large project was planned for the period from 1988 to 1990; it required $80,000 annually for a total of $240,000. In addition, $20,000 of the total was earmarked for a joint adobe preservation research project with Pecos National Monument. [63] Research historian Laura Harrison was assigned to do the historical resource study in 1988. Unfortunately, after only one season the National Park Service put the project on hold due to lack of funds.

Despite this big setback, the park staff at the monument continued to accumulate knowledge on preservation methods and techniques. In 1987, the Regional Office appropriated $2,500 to hire a special consultant to provide training in basic adobe preservation techniques, which included the selection of proper soil, the manufacturing of adobe bricks, and the coating of walls. [64] P. G. McHenry, an adobe specialist from Albuquerque, received the contract to examine soil types and recommend a suitable one. He worked closely with the preservation crew at the fort and taught workers how to use new tools and more efficient methods. In September, he and Park Service adobe specialists conducted a hands-on workshop at Fort Union. Colleagues from other state and national parks attended this session. In the end, workers improved their methods of preservation and learned a better formula for soil selection. [65]

The ruins preservation at the fort continued to improve. In the late 1980s, workers conducted their routine operations without any significant problems. Each season they manufactured more than a thousand adobe bricks. The major work, as usual, was to plaster adobe walls and do emergency repairs after severe weather. [66] Even though the park was still waiting for a comprehensive preservation plan, the crew continued to search for the best way to protect the ruins. In comparison with other parks, Fort Union had done a remarkable job in adobe preservation, and its experiences were valuable for others. Again in April 1989, Fort Union hosted a three-week workshop for colleagues from other areas. [67]

Because of their nature, adobe structures present more preservation difficulties. Since the establishment of the monument, Fort Union has lost one-third of the adobe walls (from 200,000 square feet in 1955 to the present 120,000 square feet) due to natural causes. But workers at the fort have no desire to quit. Instead, they put more effort than ever into preservation work. They are still searching for the best way to save the ruins.

After 36 years of intensive care in the National Park system, Fort Union National Monument has matured. When the Park Service adopted this historic site in 1956, there was nothing on the land except the ruins themselves. Today, the monument has appropriate support facilities: a 3.39-mile road system, a 4,000-square-foot visitor center, and 15 residential and maintenance buildings. All of them are in good condition. The most significant aspect of good care at the fort belongs to ruins preservation, in which the park staff keeps the deterioration of the ruins at minimal rate. In general, the experiences of Fort Union in preservation and development have been remarkable.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foun/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2001