|

Fort Vancouver

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

III. ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION

INTRODUCTION

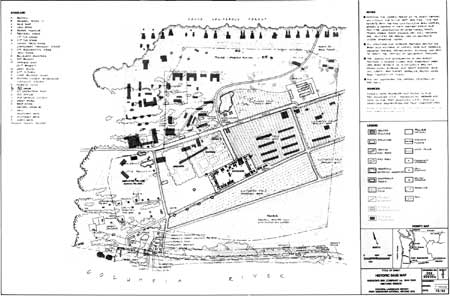

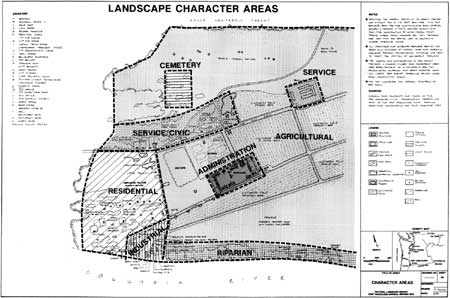

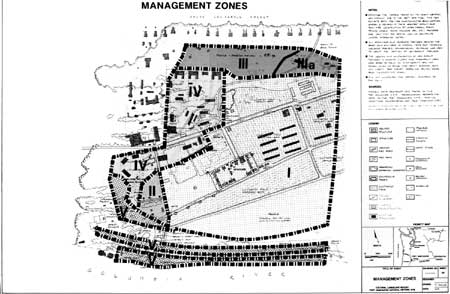

The analysis and evaluation of cultural landscape resources at Fort Vancouver is based on historical research and the documentation of the existing landscape. The purpose of the evaluation is to identify the significant landscape features, patterns, and relationships that define and comprise the cultural landscape at Fort Vancouver. These patterns and relationships are summarized and organized into seven Character Areas and four Management Zones which help set the framework for the development of Design Recommendations. The analysis and evaluation focuses on all three historic periods associated with the Hudson's Bay Company, especially highlighting the primary period of development, 1829-1844/46. While the site history for this report includes an overview of the historic development of Vancouver Barracks, it is not within the scope of the project to analyze the significance of the Vancouver Barracks landscape. In addition to focusing on the HBC occupation, the analysis and evaluation will narrow the study area to predominately address the historic "heart' of the Fort Vancouver development, the western third of historic Fort Plain. This area today is made up of land both currently within park boundaries and immediately surrounding the park (primarily Vancouver Barracks).

It is important to note that the primary source of the analysis and evaluation is the Cultural Landscape Report: Fort Vancouver N.H.S. Volume II, Landscape History, therefore research citations are not repeated. Additional data not derived from the landscape history are cited in chapter endnotes.

|

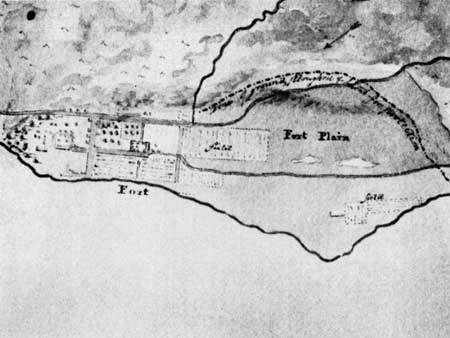

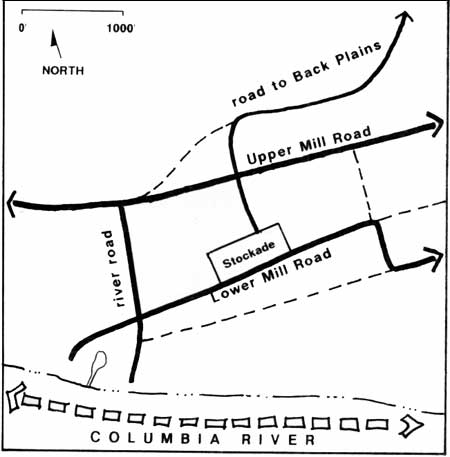

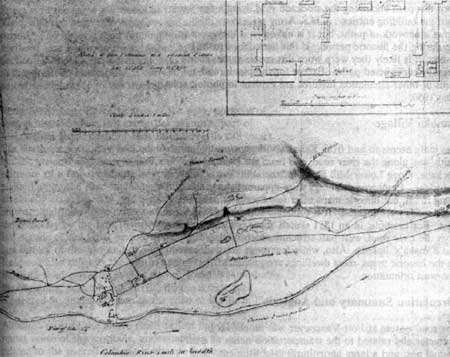

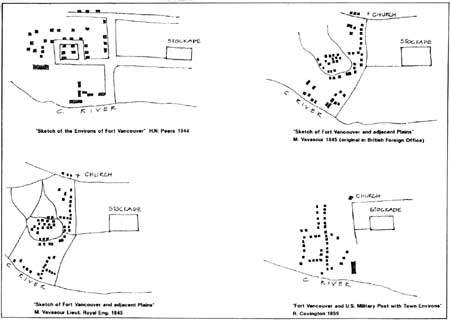

| Overall organization of Fort Plain as shown on H.N. Peers' "Sketch of the Environs of Fort Vancouver..." (post 1844). Credit: Hudson's Bay Company Archives Provincial Archives of Manitoba. |

HISTORIC CHARACTER DEFINING FEATURES

RESPONSE TO NATURAL FEATURES

|

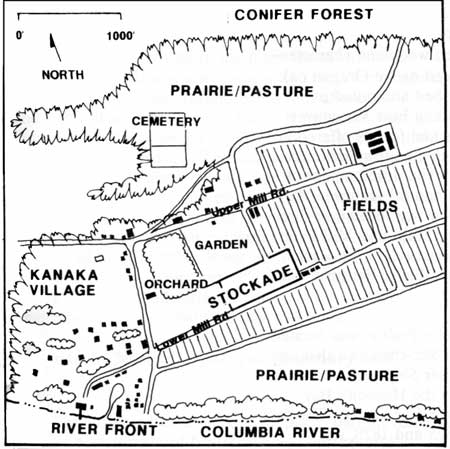

| Schematic map of the western third of historic Fort Plain showing response to natural features. |

In 1824, George Simpson, North American governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, ordered the abandonment of Ft. George and the search for a new post on the north side of the Columbia River, Criteria for locating the new post included the desire to strengthen British claims to the land north of the Columbia River, and for the HBC to render themselves "...independent of foreign aid in regard to Subsistence." The search for suitable terrain--land lacking steep banks or low, flood prone areas--ended at Jolie Prairie, about one hundred miles from the mouth of the Columbia River.

The landscape along the north shore of the Columbia River was a mosaic of natural prairies, coniferous forests, streams, and lakes. The prairies (plains) were flat, treeless expanses of land with a dense cover of grass, moss, lichens, and other low herbaceous plants. This prairie environment was self-maintaining as the dense vegetative cover was virtually impenetrable to other plants. An oak savannah transition zone often occurred between forest and plain where the topography shifted from level to sloping land. Here the landscape took on a park-like or open woodland character--prairies interspersed with widely spaced native Oregon oak and/or Douglas-fir trees--often described and noted in journals by early northwest explorers and Fort Vancouver occupants and visitors. [1] These plains and forests offered an abundant blend of natural resources that were suitable for both trade and subsistence activities. The development of Fort Vancouver was shaped by these natural features. At its height, development at Fort Vancouver was located in three large prairies called Fort Plain, Lower Plain and Mill Plain, and five smaller prairies to the northeast called the Back Plains (First Plain, Second Plain, Third Plain, Fourth Plain, Fifth Plain and Camas Plain).

The site of Fort Vancouver, called Jolie Prairie, was located near a Chinook Indian village named Ske-chew-twa that was located on the site of the W.W.I. Kaiser Shipyards. Jolie Prairie was later named Fort Plain by the Hudson's Bay Company, and became the core of Fort Vancouver. The first stockade, which operated between 1825 and 1828, was located about three quarters of a mile from the river on the edge of a terrace. This location, sixty feet above the low-lying river plain, offered protection from floods and served as a strategic defensive position from the undetermined threat of native Chinook Indians. The naturally occurring plain provided open land for agriculture, and grass for livestock pasture. The coniferous forests surrounding the plains provided a ready supply of timber for fuel and building materials. The streams on Mill Plain, six miles east of Fort Plain, provided a power source for both a grist mill and a saw mill.

In 1829, the initial stockade was abandoned and a new site for the stockade was selected on the river plain. The decision to move the fort was based on the long, difficult route from the first stockade to the river, and George Simpson's decision to make Fort Vancouver the permanent headquarters for the HBC Columbia Department, which would cause an increase in river traffic and would necessitate a larger permanent work staff to support this expansion. Like the first site, development of the landscape surrounding the new stockade was also directly related to the natural features and resources. The plain provided open land with rich soils suitable for cultivated fields and pasture, with the stockade centrally located in the plain for access to the cultivated fields. It was also close to the river for access to fresh water, and transportation needs, but above the normal flood zone. The dense conifer forest lying to the west and north of Fort Plain created a physical boundary, and provided a ready supply of timber. The oak savannah transition zone between the forest and the plain was not suitable for cultivation, but was in close proximity to major work areas, and made a logical location for the houses built by the company's employees. An industrial area was developed on the shore of the Columbia River around a pond, providing a supply of fresh water for livestock, a protected area for boat building and other industrial activities, and a storage area for supplies being transported by boats and ships.

Response to Natural Features Summary and Analysis

Fort Plain possessed an abundant supply of natural resources required for a successful fur-trading and agricultural operation: a major river and streams for transportation, power, and fresh water; favorable climate and soil for farming; large areas of grasslands for livestock pasture; timber for building material; and plenty of open (non-forested) land for expansion of the fort as development proceeded. Overall, the development of Fort Vancouver was directly tied to the availability and location of natural resources on Fort Plain; the forests, prairies, topography, and river all playing a role in directing the location and character of both individual landscape features and overall site organization.

Today many of the natural features of the site have been greatly impacted by development; some have disappeared entirely. The large coniferous forest that defined the western and northern boundary of Fort Plain, and the pond located in the riverfront area, no longer exist. The overall spatial relationship and connection between the reconstructed stockade and the river, which is critical to understanding the historical context for Fort Vancouver, has been degraded by the Burlington Northern railroad berm, Interstate 5, Highway 14, and Columbia Way. Despite these physical intrusions, some of the historic character of the site still exists. For example, the overall topography of the site, a gentle slope from the parade ground to the river, remains essentially the same. In addition, although the development surrounding today's stockade has eroded the quality of the historic open plain, the open spaces of both the Vancouver Barracks parade ground, and the southern half of Pearson Airpark, help retain the open space character of the historic fields and prairies.

OVERALL ORGANIZATION

|

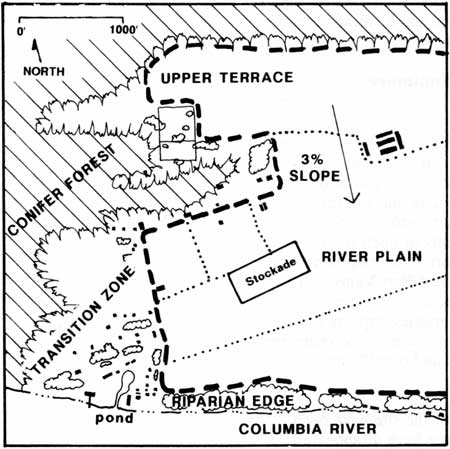

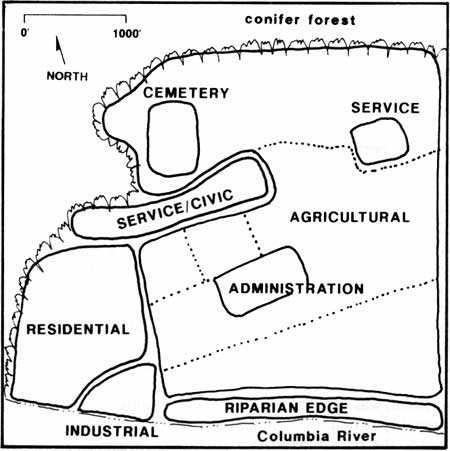

| Schematic map of the western third of historic Fort Plain showing overall organization. |

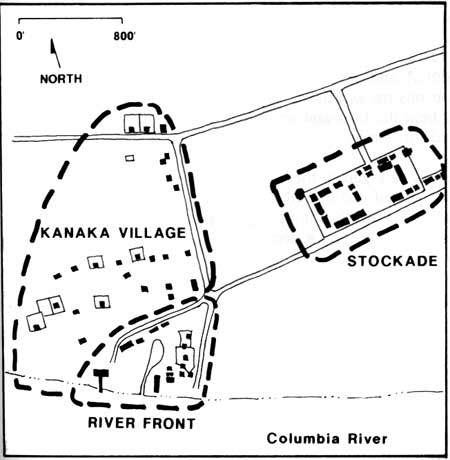

Fort Plain was historically defined by a dense stand of conifers to the west, north, and east, and by the Columbia River on the south. This forest acted as a natural boundary, separating the site spatially and functionally from other areas of development. The developed area on Fort Plain consisted of the stockade, which acted as the core of the fort, with other landscape features radiating out from this center. Cultivated fields, pastures, the garden, and the orchard were adjacent to the stockade. West of the stockade was Kanaka Village where HBC employees lived, and to the southwest along the river was an industrial area. A scattered collection of service/civic buildings was located north of Upper Mill Road.

Stockade and Vicinity

On Fort Plain, the fort stockade served as the administrative core of the site with other features spreading out from this center. The stockade included a major living area for higher-graded Company employees, and a storage and service area for many aspects of fur-trading, industrial, and agricultural activities. In ca. 1846, there were twenty-five structures located within the stockade. In addition, there were a few buildings located outside the southeast corner of the stockade and additional structures located southeast of the stockade along the Columbia River. Roads radiated outward from the stockade, accessing features on Fort Plain as well as the river and outlying plains.

Development of the area in the vicinity of the stockade coincided with the new stockade's construction in 1828-29. Generally, the area was organized in response to functional needs, which also related to the existing physical landscape. Agricultural activities were located on cultivable land near the stockade for easy access. These agricultural features included: the garden and orchard to the north and northwest; cultivated fields to the northeast and south; and the prairies along the river and north of Upper Mill Road that periodically served as livestock pasture. Features established ca. 1829 included the garden, cultivated fields, the grist mill, and at least one barn. As the Fort's trading and agricultural influence increased, the physical development of this area also expanded. Between 1829 and 1846, the stockade doubled in size, more fields were cultivated, agricultural structures were added including a barn complex, the orchard (as distinct from the garden) was established, and more roads were constructed.

After 1846, Fort Vancouver's influence began to decline due to a variety of circumstances including the 1846 boundary treaty between the United States and Great Britain, Chief Factor McLoughlin's departure in 1846, the transfer of HBC administrative duties to Fort Victoria, and the arrival of the U.S. Army in 1849. By the mid-1850s, stockade buildings were poorly maintained and by 1860, most of the remaining twenty-two buildings were described as in "ruinous condition". In 1860, Fort Vancouver was abandoned by the HBC.

While the outlying plains of Fort Vancouver farm began to be etched away by pressure from American settlers and the army, an effort was made to maintain the area immediately outside the stockade. Documentation suggests that activities in the fields, garden, and orchard continued by the HBC, if only at a reduced level, until 1860.

Area North of Upper Mill Road

Documentation indicates the area above Upper Mill Road evolved gradually. In addition to the agricultural development that began in 1829, non-agricultural development began in the 1830s and included the construction of residential buildings associated with Kanaka Village. In the mid-1840s several civic buildings were constructed including a church and schoolhouses, along with a couple of privately owned structures. Most of the development occurred in close proximity to the north side of Upper Mill Road.

By 1846, the area north of Upper Mill Road contained scattered Hudson's Bay Company structures including the St. James Mission, two schoolhouses, a barn complex and employee dwellings; privately owned structures, Ryan's house and a stable; and a large cultivated field. The prairie north of the developed area was used periodically for livestock pasture. A cemetery was located on the west side of this prairie. The development was accessible from Upper Mill Road and the road to the Back Plains, which had a spur connecting it to the river road.

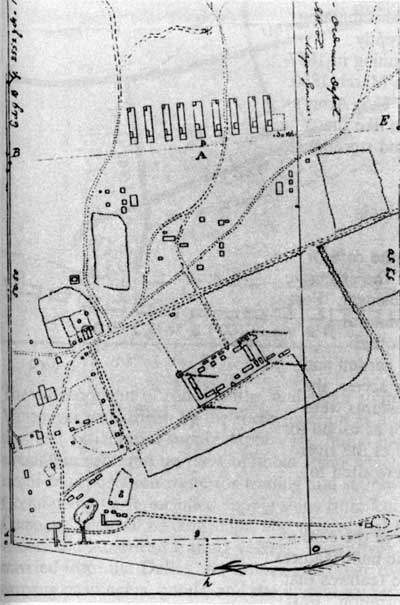

Between 1846 and 1860, this area experienced significant changes as the Hudson's Bay Company influence waned and the U.S. Army's presence began to dominate development. By 1860, the army had created a new settlement north of Upper Mill Road in the form of army barracks and associated structures, a large parade ground, and new roads. This area would remain the core area for Vancouver Barracks for many decades, with remnant features from its early development still in existence today.

|

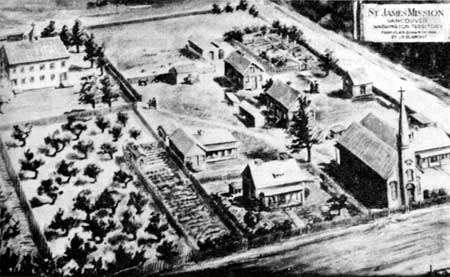

| 1851 illustration by George Gibbs of view northeast from Kanaka Village towards remnants of the HBC developed area north of Upper Mill Road including St. James Mission, employee dwellings, and the schoolhouses. The U.S. Army development is in the distance. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo file. |

Kanaka Village

West of the stockade and the river road, and south of Upper Mill Road, was the main portion of Kanaka Village, the Company's employee residential area. Much of the village was located on the relatively flat terrain that sloped slightly from Upper Mill Road to the river. The western boundary of the village was defined by the conifer forest. By 1846, the majority of the dwellings associated with Kanaka Village lay south of Upper Mill Road, and north of Lower Mill Road. In addition to this core developed area, a few dwellings were located north of Upper Mill Road, and a few in the river front area.

|

| 1851 George Gibbs illustration. View east from Kanaka Village towards the stockade. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo file. |

Detailed information about Kanaka Village remains unclear. Its development probably coincided with the stockade's move to Fort Plain in 1829, and possibly preceded this move. The number of dwellings reported in the 1830s and 1840s varied between thirty to fifty structures. From 1849 to 1860, the area was transformed from an active HBC residential area to the U.S. Army's quartermaster depot. The decline of Kanaka Village began in the late 1840s as employees left the fort in search of gold in California, and by 1850, much of the population had dispersed. This decline was hastened by the arrival of the U.S. Army in 1849 and the beginning of the quartermaster depot. The army development included dwellings, shops, stables, roads, and several buildings rented from the HBC. By 1860, virtually nothing remained of the HBC Kanaka Village, due to both the decline of the Company and the aggressive clearing and demolition of HBC property by the U.S. Army.

River Front area

In this report, the river front area refers to the historical complex of structures sited around a pond between Lower Mill Road, the lower portion of the river road, and the Columbia River. These two roads and the river were the primary circulation routes for the area.

|

| Detail of the 1854 map of the Military Reservation of Fort Vancouver by Lt. Col. B.L.E. Bonneville, showing changes to the HBC landscape as the U.S. Army development grew. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. map file. |

The evolution of the river front area is understood only generally. Early development was probably related to transportation activities which changed with the relocation of the stockade in 1829. By 1846, industrial activities included shipping and storing goods, shipbuilding and repair, coopering, tanning, and for a time, distilling. Employee dwellings, sheds, and stables were also located in the area. The exact number and location of structures in this area remains unclear. The river front area, as with Fort Vancouver as a whole, gradually declined between 1846/47 and 1860. Documentation suggests several structures survived during this period including three dwellings rented by the army; a house used as a hospital; boat sheds; a bridge (possibly a second bridge built by the army); a distillery; and the salmon store and wharf. By May 1860, these remaining structures were also gone. The army was apparently responsible for much of this later clearing, beginning in 1857-58 and ending with a major demolition effort in March 1860. At that time, the river front became part of the U.S. Army's quartermaster depot development serving, much like the Hudson's Bay Company period, as a shipping and storehouse area.

Overall Organization Summary and Analysis

The landscape features of Fort Plain served as the core or "heart", both functionally and geographically, of the extensive Hudson's Bay Company operations at Fort Vancouver. Fort Plain was organized according to function and natural features. The stockade served as the hub with other landscape features expanding out from it. The garden and orchard were adjacent to the stockade for close access, the fields were located on easily cultivated land, pastures were located on the part of the prairies that were not as useful for growing crops, industrial activities were located at the river for easy river access, and employee quarters were sited to provide proximity to work areas.

Today, while the reconstructed stockade serves as the core of the interpretive site, there are no extant historic built features and few interpretive or reconstructed landscape features that lend an understanding to the historic site organization. East Fifth Street (historic Upper Mill Road) still acts as a strong organizing feature, and open spaces of the parade ground and Pearson Airpark can serve as a reminder of the spatial relationship of the stockade to the fields and pastures. The river and reconstructed stockade reflect their historic locations; however, physical and visual barriers greatly impact their relationship. [2]

CIRCULATION

|

| Schematic map of the western third of historic Fort Plain showing circulation patterns. |

The development of roads, paths, and water routes at Fort Vancouver was driven by the fort's function as a fur-trading post and agricultural supply depot. The initial focus of circulation centered on the Columbia River which provided a major transportation route for trading and supply vessels. Ocean-going trade included supply ships from London, the Company's coastal trading ships, and occassional Royal Naval vessels and American trading vessels. Downriver traffic traveled from the Dalles, via canoes and other river vessels, carrying passengers, goods, and the annual express from York Factory in Canada. Although the river served as the primary system for moving goods and supplies for the fort, as Fort Vancouver developed, land access within Fort Plain to outlying plains and inland waterways--the Little River and the Big Lake (today Vancouver Lake)--became increasingly more important.

Little is known about the earliest roads and paths surrounding the fort between 1824 and 1828. An 1825 map, the only map from this period, generally shows a single road extending from the river to the stockade in a straight line. [3] The exact location of this road in relation to the second stockade is uncertain, as are the existence or locations of other roads and paths.

During the historic period, 1829-1846, the early sequence of road and path development is ill-defined. Generally, however, documentation suggests circulation initially focused on access from the stockade to the river. Then it gradually expanded outward from the stockade as the need for traveling to developed areas within Fort Plain and to outlying plains increased.

By 1844, principal land access consisted of paths and roads which radiated outward from the Fort stockade. The arrangement of roads around fields and pastures, created a grid-like pattern. While these dirt roads followed fairly well defined routes, due to wet, muddy conditions, their widths and exact locations probably varied slightly both seasonally and over time. [4]

In 1846, primary roads consisted of the north/south running river road; the Lower Mill and the Upper Mill Roads (east/west roads which connected the stockade to other plains); and a road leading northeast to the Back Plains. The river road began at the river below the salt house where ships usually anchored, intersected with Lower Mill Road and continued north between the orchard and Kanaka Village, terminating at the Upper Mill Road. The main entrance gates to the stockade were on the south side. On Lower Mill Road, at the intersection of the river road, a tall wood post and beam gate appeared to have been built as the "formal" entry to the stockade area.

The Back Plains road began at the intersection of Upper Mill Road and the road from the north gate of the stockade, ran north past the school houses then curved northeast across the prairie before entering the forest and continuing northeast to the Back Plains.

By 1846, secondary roads included: a short spur from St. James Mission to the Back Plains road; a road south of, and parallel to, Lower Mill Road (which provided a more direct route between Mill Plain and the riverfront area); and a road running south from the Upper Mill Road barn complex, between fields, and extending past Lower Mill Road.

|

| "Sketch of Fort Vancouver and Adjacent Plains", by Lt. M Vavasour, 1845, showing the physiographic features and circulation patterns of Fort Plain. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo file. |

Stockade interior

Most details about the circulation patterns in the stockade remain unclear. The two gates on the south side of the stockade served as the main entry between the river and the stockade. At the southwest gate there was a wooden plank road running between the second fur store and the provisions store that ended in the center of the yard. The plank road was eight to ten feet wide and approximately seventy feet long and appeared to be associated with a drainage system. Access from the north side of the stockade was through a gate between the Chief Factor's House and the Priest's house.

Documentation on paths within the stockade is scarce. In the 1846-47 Coode watercolor, it is possible to make out a well-worn dirt path encircling the stockade yard, lying a few yards from the building entries. A U.S. Army map from 1854 shows a network of paths, but it is unknown if they were in use during the historic period. If this network of paths is correct, it is likely they were worn dirt routes rather than formally constructed paths. Except for the plank road, no paths or other circulation features are evident in photographs from 1860.

Kanaka Village

The main access to and from Kanaka Village, traveling north-south, was along the river road, and from the river to the stockade, along Lower Mill Road. Circulation inside the area is unclear. Employee dwellings were apparently organized along roads, but historic maps offer few details on where these roads were located. It is probable some roads ran east-west. For example, in an 1851 sketch, there is a road running from the river road, west past structures identified as "Billy's and Kanaka's" houses. Also, while few roads are delineated on the historic maps, most dwellings are generally sited in an east-west orientation.

Circulation Summary and Analysis

The road system at Fort Vancouver was functional in character and related to the transportation needs of a fur-trading post and a large agricultural establishment. The circulation system began with primary access, which was from the river to the stockade, and expanded to roads within Fort Plain, and to distant farm plains and overland trade routes. Providing access was critical to the success of a remote trading establishment and these early roads and the river front access point became significant landscape features.

Although most of these routes changed somewhat after the HBC occupation, many early roads were used by American settlers and contributed to development of the area by the U.S. Army.

Today, some important portions of the historic circulation pattern are still extant. With few modifications, East Fifth Street is in the same alignment as the historic Upper Mill Road, and has been in continuous use since the historic period. The historic road running north from the stockade's northern gate has been reestablished by the National Park Service. Although the north gate was not the main entrance to the stockade historically, it currently serves as the main pedestrian entrance to the stockade.

In the Vancouver Barracks area of the park, portions of several historic roads still exist. For example, part of McLoughlin Road north of East Fifth Street is still intact. The southern portion of McLoughlin road is no longer intact, but the general alignment is discernible because of the existence of a few remaining large deciduous trees that were planted along the road in 1883. While this road was essentially established by the army in the early 1850s (the northern half may have existed as crude HBC road or path to the cemetery by the late 1840s), it was in existence during the last decade of the HBC period, and is significant to both the late history of the fort and to Vancouver Barracks' history. Research also suggests the southwest part of the Vancouver Barracks road currently named Alvord Road, was probably the beginning portion of the HBC diagonal spur that connected St. James Mission to the road to the Back Plains. [5]

Although most of the above roads reflect important access routes north of the stockade, understanding the circulation related to the overall historic landscape is more difficult since many other roads existing in 1844-46 are no longer extant, and/or have not been reestablished. The most important the missing historic routes are the primary access roads from the river to the stockade. Today there is no pedestrian or road access from the river to the stockade due to the significant alteration of the landscape by major highways and the railroad embankment. The lack of connection between the river and the stockade, and the use of an inaccurate main entry to the stockade, compromise the historic scene and neglect the critical relationship between the Columbia River and Fort Vancouver.

LAND USES AND ACTIVITIES

|

| Schematic map of the western third of historic Fort Plain showing land uses and activities. |

From its inception, a wide variety of land uses occurred at Fort Vancouver reflecting both the fur-trade industry and agricultural operations. Land use activities included administration, domestic activities, trading, social/recreational activities, agricultural activities (large-scale cultivation, livestock, and local subsistence), industry, and service-related activities.

Administrative/Working and Residential Hub

The fort stockade served as the center of Fort Vancouver operations and internally supported many land uses including administrative activities (offices), trade activities (open space for trading and stores for selling supplies), warehouses, living and societal uses (dwellings, kitchens, privies, wash house, church, the schoolhouse, jail), and industry-related activities (blacksmith shop, harness shop, iron store).

Employee Residences

Kanaka Village served as the major residential area for Hudson's Bay Company employees. There were also dwellings in the river front area, and a few other scattered dwellings, located southeast of the stockade along the river, belonging to employees and possibly officers of the ship Modeste.

Agriculture

There were three land-use activities related to agricultural operations at Fort Vancouver; raising produce for large-scale cultivation, large-scale livestock breeding, and local subsistence. For detailed discussions of these agricultural practices refer to the individual topics addressed in the section on Vegetation, pages 57 to 78.

Large-scale cultivation

The goal of creating a self-subsistent HBC fur-trading operations in the Pacific Northwest was achieved at Fort Vancouver through large-scale crop cultivation. Cultivated fields on Fort Plain were located northeast, east, and south of the stockade. Related structures such as barns and root houses were sited within or adjacent to fields.

Livestock Breeding

In addition to raising produce to become self-subsistent, large-scale livestock breeding was also undertaken at Fort Vancouver. The prairie adjacent to the river was sown timothy and clover and used periodically for pasture. This pasture was also occasionally used for horse racing between the crew or officers of the ship Modeste, and Company employees. The prairie on the north edge of Fort Plain, above Upper Mill Road, was also probably used as livestock pasture.

Local Subsistence

Raising produce for local consumption primarily took place in the fort's garden and orchard. These two areas supplied fresh fruit and vegetables for HBC employees at Fort Vancouver. Evidence indicates most produce was served only at the mess table of HBC officers, clerks, guests, and to select employees and visitors in the Chief Factor's kitchen.

Industry-Related Activities

The river front area consisted of a cluster of buildings surrounding a pond. While individual structures came and went during the historic period, over time the use of the area remained fairly consistent. It supported many industrial activities, including ship building and repair, barrel making (coopering), shipping, storing, hide tanning, and, for a time, distilling. A few employee dwellings and a hospital were also located here. In addition, horses (probably used for pulling carts and wagons), working oxen, and pigs were housed in sheds and stables in the area. Generally, by 1846, industrial structures and activities were located closest to the river, stables were along the west or northwest edge of the pond, and dwellings were along the east side of the pond.

Service/Civic activities

North of Upper Mill Road there were two service/civic areas located in close proximity to the road. In the western area, buildings included a grist mill, stable, church (St. James Mission), and schoolhouses. The east service/civic area was the barn complex that was located east of the cultivated field.

Cemetery

In 1846, a cemetery containing the graves of Company employees was located north of St. James Mission on the west edge of the prairie.

Land Use Summary and Analysis

The landscape of Fort Plain functioned according to land uses appropriate to a fur-trading and agricultural establishment. Administrative areas, residential areas, industrial areas, and agricultural areas were all part of this large and complex operation. Presently, the reconstructed landscape features of Fort Vancouver represent only a portion of the historic land use practices. Existing reconstructed features such as the stockade focus on the administration of the fort, fur-trade and other work activities, and the chief factor's house. Additional interpretation of agricultural operations is represented through the interpretive orchard and garden.

VEGETATION

|

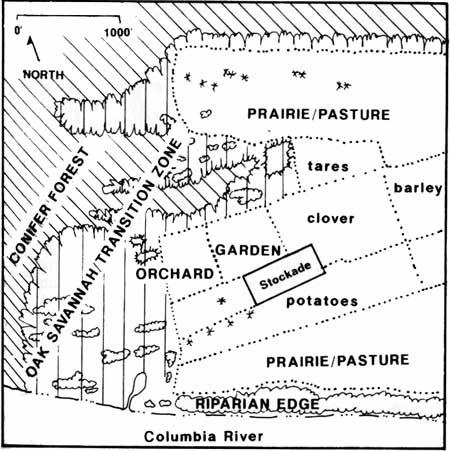

| Schematic map of the western third of historic Fort Plain showing vegetation. |

The physiographic features of Fort Plain, including vegetation, set the framework for the trading and agricultural activities that were introduced to the region by the Hudson's Bay Company. As development at Fort Vancouver proceded, native vegetation gave way to introduced vegetation in the form of cultivated fields, pastures, a garden, and an orchard. The expansive agricultural operations developed at Fort Vancouver represented the first large-scale agricultural establishment in the Pacific Northwest.

|

| "Sketch of Fort Vancouver Plain, Representing the Line of Fire in September 1844". Agricultural development on Fort Plain. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. map file. |

Native Vegetation

Before the establishment of Fort Vancouver, the natural landscape was a mosaic of prairies (plains), coniferous forests, streams, and lakes. Early visitors and Company employees often commented on the natural beauty of the country, noting the lush, dense forests with magnificent trees, carpets of wild flowers, extensive prairies with their groves and clumps of trees, lakes, and views of the Columbia River with snow-capped Mount Hood in the distance.

Fort Vancouver lies in the northern tip of the Willamette Valley vegetation community, part of the major vegetation zone "Interior Valleys of Western Oregon". [6] Historically, this area consisted of grasslands or prairies, Oregon oak savannahs, coniferous forests (mainly Douglas-fir), and riparian forests. A partial list of native plant species was developed from both contemporary plant community descriptions and historic references (see Appendix A).

As Fort Vancouver developed, the native vegetation was replaced by introduced species. On Fort Plain, the prairie and some forested areas were cleared for cultivated fields, livestock pastures, the garden, orchard, buildings, and roads. By 1844/46 little of the immediate fort site remained unmanipulated. Remimants of the natural landscape included the coniferous forest lying at the north edge of Fort Plain, which had probably been reduced along the perimeter by clearing for cultivated fields. On the west part of the plain, the forest edge and prairie north of Upper Mill Road consisted of individual specimens and clumps of Douglas-fir and Oregon oak trees. In 1833, Dr. William Tolmie, a HBC employee, described this prairie and the cemetery, noting that the cemetery was reached by traveling through "a pretty grove of young oaks & other trees", situated "...in a fertile upland meadow greatly beautified by wild flowers & trees in flower..."

Other native vegetation that remained after the site was developed included: individual trees or clumps of trees in Kanaka Village which were part of the oak savannah transition vegetation zone; several individual trees including five large Douglas-fir trees near the stockade along Lower Mill Road; and a band of riparian vegetation which bordered the Columbia River east of the river front development. William Tolmie described the river bank as "... a nice pebbly beach, well suited for bathing & edged with verdant trees & elegant wild flowers of various species."

As development progressed during the Hudson's Bay Company era and later during the Army's occupation, the remaining forests and prairies continued to be cleared for fields, buildings, roads, and timber, leaving few of the native plant communities intact.

Cultivated Fields

The Fort Vancouver farm, the first large-scale agricultural establishment in the Pacific Northwest, was created for economic and political reasons. In order for the Hudson's Bay Company fur-trading operations west of the Rockies to succeed, it was necessary to reduce the huge transportation expenses associated with importing food. Creating a self-subsistent operation was critical for supplying Fort Vancouver's needs, and the needs of outlying fur trading posts. As the farming operations expanded it was soon realized that in addition to fur trading, profits could be created through exporting surplus produce. Food exportation further diversified the Company's west coast operations. Politically, it was assumed Great Britain's claim to the territory would be enhanced by eventually attracting British immigrants through this agricultural development.

Agricultural activities began in 1825 with the planting of potatoes, beans, and peas, and slowly expanded to include a wide variety of grains and vegetables which covered extensive tracts of land. By 1846, the Fort Vancouver farm had 1420 acres under cultivation and was made up of several operating units which included Fort Plain, West Plain, Lower Plain, the Back Plains, and Mill Plain. At its height, a wide variety of crops were raised at Fort Vancouver farm including great quantities of wheat (the most important cash-barter crop), peas, barley, oats, buckwheat, some Indian corn, and potatoes. In addition, turnips, pumpkins, tares, and colewort were raised for livestock, and timothy and clover were raised for soil enrichment and livestock food. A list of crops cultivated on Fort Plain can be found in Appendix B.

As McLoughlin became aware of the limitations of the soil at Fort Vancouver, Cowlitz farm and Nisqually farm were established nearby. In addition, both Fort Langley on the Lower Fraser River, and Fort Colvile on the upper Snake, received their agricultural supplies from Fort Vancouver. The creation of the Puget Sound Agricultural Company in 1839 further expanded crop production by increasing the Company's commitment to agricultural exports. Throughout this agricultural expansion, Fort Vancouver remained the operational hub and main production post for all the Columbia Department's farming operations west of the Rockies; operations that were noted by one visitor as being conducted on a "stupendous" scale. After 1846 the farm began to decline, suffering from squatters, a reduced labor force, increased costs from territorial taxes and duties, and competition from crop production by settlers.

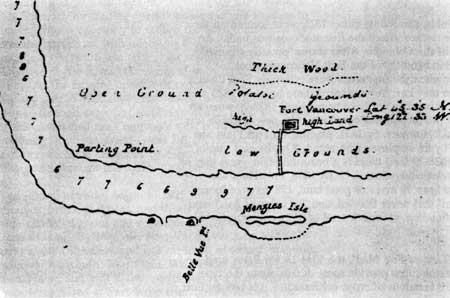

The first fields, planted in spring 1825, were located on the upper river terrace where the first stockade was built. An 1825 map of the Columbia River shows "potatoe grounds" located behind (north) of the Fort Vancouver stockade. It is not clear when the first crops were grown on Fort Plain. Some crops may have been planted there between 1825 and 1828 or planting may not have begun until 1828-29 when an increase in production was noted after the new stockade was constructed. However, by 1831, planting on Fort Plain was confirmed by an employee who noted, "On the east side of the Fort [1828-29 fort] there is a beautiful plain, great part of which is under cultivation. . .". By 1838, Fort Plain was reported to have 70 acres of good land, 178 acres of "poor shingly land" that never flooded, and 203 acres of good land subject the to flooding--at most a total of 457 acres of cultivable land.

The 1844 "Line of Fire Map", the 1844 Henry Peers map, and 1846 Covington maps provide some details about the type, acreage, and locations of crops cultivated ca. 1844-46 on Fort Plain. While there are discrepancies among these maps, they generally indicate that there were from 150 acres to 220 acres of land fenced and cultivated on Fort Plain at the height of the fort in ca. 1844/46.

In 1844, the stockade was surrounded by fields laid out to the northeast, south, and southeast. Across Upper Mill Road between the schoolhouses and the barn complex was a six acre field of tares planted as livestock food; adjacent to the stockade was a twenty acre clover field used as livestock food or as soil enrichment; a twenty-five acre barley field east of the clover field; and east of the barley, an eighteen to twenty acre cole seed (or rape) field, used as either a forage crop, a cover crop, or to produce rape oil. South of the stockade was a twenty acre potato field, and east of the potato field was a sixteen acre barley field. The 1844 Peers map also shows an irregularly shaped field of about forty acres in the southeast area of the plain (outside the current park boundaries); it is not known what was planted there.

|

| 1825 Map of the Columbia River showing the first stockade at Fort Vancouver. of map on file in the Washington State Historical Society Special Collections. |

In addition to these fenced fields, documentation indicates that timothy and clover were planted as pasture for horses and cattle. On Fort Plain, this practice applied to the land between the cultivated fields and the Columbia River. The prairie north of the tare field and barn complex was probably also used as pasture and may have been planted with timothy and clover, or left in native grasses. Fences were used to enclose cultivated fields in order to keep livestock out during the growing season, and to contain them when manure was folded onto fallow land.

Administration of a farm of this scale required a great deal of knowledge and skill. The overall management of the farm was directed by Chief Factor McLoughlin, although as the farm expanded, London sent agricultural experts such as dairy operators, general farmers, and shepherds to assist with operations. Some information about farming methods exist in the historic literature and more detailed information can probably be obtained from the two books found in McLoughlin's library, Cattle Doctors, and John C. Loudon's Encyclopedia of Agriculture: Comprising the Theory and Practice of the Valuation, Transfer, Laying Out, Improvement, and Management of Landed Property. For example, in Loudon's Encyclopedia of Agriculture... under the heading "General Processes common to Farm Lands", the merits of crop rotation, "working of fallows, and the management of manures" are discussed. [8]

At Fort Vancouver, soil improvement was a major management concern, especially when it was realized that the soil, initially proclaimed as being exceedingly fertile, was found to be poor in many areas. Strategies to improve the soil mirrored those presented in Loudon's work including crop rotation, fertilizing with manure, and allowing fields to lie fallow. For example, in 1842, Chief Trader James Douglas, stationed at Fort Vancouver, recommended that the manager at Fort Nisqually sow the wheat field at the dairy with timothy and clover. Clover, timothy, and probably rye grass (listed on the 1831 seed list) were raised at Fort Vancouver, presumably both for soil enrichment and livestock forage.

Periodically fields were allowed to lie fallow for a year; the Back Plains fields rested for four years after a crop was harvested. In addition, fallow fields often had manure applied to them. James Douglas said that in addition to rotation, the farm methods at the post consisted of "...keeping the soil in good heart, by fallowing and manures, the latter operation being most commonly performed by folding the cattle upon the impoverished land." Cattle and sheep were apparently also penned at night on the fields at Fort Vancouver and Fort Nisqually to help the soil produce. At Cowlitz Farm, and probably at Fort Vancouver, Indians carted manure from the barns to the fields and also fertilized the land with "muck from the pig sties."

To maximize production, McLoughlin instituted several strategies including selective land use, in effect matching crops or uses with soil conditions and field locations. For example, land subject to annual flooding was taken out of cultivation completely, or planted with timothy and clover and used as livestock pasture. Land flooded only in unusually high water was occasionally replanted for a second late crop, after the water receded. Also, early in the farm's history, McLoughlin matched crops and soil fertility, determining that Indian corn required the best soils, followed by barley, wheat, and then oats or peas.

The planting process at Fort Vancouver consisted of plowing the soil, sowing the seed, and then using a harrow to cover the seeds. Plowing and sowing times depended on the weather and crop. Documentation indicates that plowing was commonly carried out all winter, except when frost was on the ground. Oats, peas, potatoes, barley and buckwheat, turnips, and fall wheat were sown in early spring. Potatoes were usually planted by hand in spring, at least once in June, and harvested in late fall for seed and post rations. Garden peas were planted in early spring harvested in May: field peas harvested in mid-summer. Fall crops at Fort Vancouver included some potatoes and winter wheat, while at Fort Nisqually, December and January plantings included timothy and clover, in addition to turnips and colewort for seed.

At least two cast iron plows drawn by oxen and horses were used in the 1840s. At Cowlitz farm, a "2 Wheel Plough" and a "big Norfolk Plough" were used, and at Fort Vancouver a new "draining plough" for light soils arrived in 1841. By 1843, a seed drill had been requisitioned by McLoughlin for sowing (probably for grains). Originally, sowing was likely done by hand, although since drills were available from agricultural warehouses in England by 1821, they may have been in use at the farm prior to 1843.

Harvesting grain at the farm was similar to practices common in the British Isles in the first half of the nineteenth century. The majority of the grain at Fort Vancouver was harvested in the summer and fall. Grains or hay crops were cut using hand-held scythes and reaping cradles that were attached to the scythe handle to catch and stack cut stalks. Sickles were also used for hand cutting grains or weeds. In 1836, McLoughlin inquired about the potential of ordering a new type of reaping machine discussed in Loudon's Encyclopedia of Agriculture..., but there is no indication it was sent to the post.

After cutting and binding the grain, the sheaves were stored in the barns until they could be threshed and winnowed. Until 1839 there were no granaries for storage, and improper storage in barns often led to a great deal of spoilage. Contributing to this problem was the limited labor supply which often delayed threshing until winter months when post activities slowed. Threshing methods progressed over the years at the farm. In 1829, threshing was done with horses, "in the circus", probably a wood or dirt treading floor in a barn. By 1834 a stationary, horse-powered threshing mill was used to operate a sweep or lever-type of power, with horses walking in a circle. By the early 1840s, portable threshing machines were in use and by 1844 the fort had two, four horse-powered machines imported from England, and one "country made" at Fort Vancouver.

After threshing, seeds from grains, peas, and grasses had to be cleaned by winnowing. Performed by hand initially, by 1844 fanning mills, a pair of "English Fanners" and another, "country made", were used to chaff dust and dirt away. Other crops such as peas, clover, flax, and timothy were also processed this way at Cowlitz and presumably at Fort Vancouver.

Farming tools, as noted above, were both imported and "country made". British suppliers included Bryan Corcoran & Co.; John Davis; Ransomes & Sims; Mary & Thomas Wedlake; and Evans & Lascelles (specifically for dairy implements). A list of agricultural tools used at Fort Vancouver can be found in Appendix C.

Livestock Pastures

Initially, livestock was raised at Fort Vancouver to supply the Company's posts and Columbia Department coastal vessels, with salted beef, pork, and dairy products. Over time, however, livestock operations grew to such a large-scale that it dominated the region's supply. In addition to raising cattle and hogs, raising horses was later instituted to support the large-scale farming and fur-trading needs. Due to the demands of the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, sheep eventually became the most dominant livestock raised at Fort Vancouver and in the region. Cattle, hogs, horses, sheep, goats, and oxen were also raised at Fort Vancouver farm, although a majority of these operations were carried out in locations other than Fort Plain.

In 1825, horses and cattle were pastured on Fort Plain in the area below the fort, presumably roaming freely among any fenced cultivated fields that existed at the time. Hogs were also allowed to range freely on both the upper prairie or the plain below. By 1828, goats were kept at the farm, although it is not known where.

Between 1829 and 1846, as cattle, horses, and sheep numbers increased, most were moved to Lower Plain and Mill Plain. However, livestock was never completely absent from Fort Plain. Sporadic references during this period, note that livestock were located in the vicinity of the stockade and along the river. The location of a pasture in the vicinity of the stockade probably refers to the prairie north of Upper Mill Road. In 1838, it was noted that the land near the fort was not adapted for large-scale herding. However, documentation suggests it was used periodically because it was also noted that, when the only "tolerable pasture" near the river was flooded, the cattle were moved into the barns on Fort Plain, Mill Plain, and Lower Plain.

In the 1840s, the land along the river was sown with timothy and clover and used for pasturing cattle and horses. Dairy cattle, horses, and oxen, used for work at Fort Plain, were kept at the stable and ox-byre near the river front. In addition to roaming freely on the plain, cattle were sometimes penned on cultivated fields at night to manure soil and sometimes in movable pens on areas destined for cultivation.

Garden

A garden at Fort Vancouver probably dated back to as early as 1825, coinciding with the old stockade which existed between 1824 and 1828. During this period, garden seeds were supplied by a variety of sources including Gordon, Forsythe & Co.; the Horticultural Society of London; and individuals such as Lt. Aemilius Simpson who planted apple and grape seeds in 1827 (his story of how some grape and apple seeds arrived at the fort is one of several versions). References to "extensive gardens" leave no doubt to its existence, however, it is not known if it was located on the bluff near the old stockade, on Fort Plain near to where the new stockade would be built, or elsewhere on Fort Plain. Wherever the original garden was located, it appears that after the new stockade was constructed in 1829, a new garden was laid out directly behind it (north).

The new garden appears to have reached the height of its development ca. 1844 when it reached eight acres in size, and continued to be tended on some level until the HBC departed in 1860. Due to the overall decline in Fort Vancouver activities during later years, and the death of William Bruce, the garden's primary gardener, the intensity of planting in the garden and the care it received also declined between 1847 and 1860. By 1860, the garden, or "orchard" as it was called by then, had been reduced to four acres.

The general development of the size and location of the new garden is also unclear. References from the 1830s and 1840s offer only general descriptions, and no known extant plans or planting schemes have been discovered. Early descriptions offer some sense of its size and substance yet no maps or descriptions indicate its size until 1844. For example, in 1836 missionary Narcissa Whitman noted, "Every part [of the garden] is very neat and tastefully arranged fine walks, each side lined with strawberry vines. On the opposite end of the garden is a good Summer house covered with grape vines.". Also in 1836, missionary Henry Spalding wrote "We were soon conducted by the Doct. [doctor] to his Garden. . . where we did not expect to meet. . . such perfection in gardening. About 5 [five] acres laid out in good order, stored with almost every species of vegetables, fruit trees and flowers."

The original size of the garden may have coincided with the pre-1834 stockade size, approximately 320 feet, which then expanded along with the stockade, and reached its full development in 1844. The 1844 "Line of Fire Map" is the only map known to delineate both the size and some spatial organization to the garden. [9]

The 1844 fenced garden enclosed a large rectangular area approximately 570 by 625 feet (about eight acres) that was oriented east-west. It was located between the stockade and Upper Mill Road, and between the north gate road and a fence that extended about 140 feet beyond the west wall of the stockade. It was laid out in an irregular pattern of three by three rectangular beds enclosed by paths. Individual beds ranged in size from 85-140 feet long to 130-150 feet wide and were separated by paths twenty to thirty feet wide. In addition, two long narrow beds lay on the west and south sides of the garden: the south bed, adjacent to the stockade wall, was approximately five hundred feet long and fifty to sixty feet wide; and the other bed was approximately seventy to eighty feet wide and six hundred feet long and lay along the west boundary fence.

Structures in the garden included a summerhouse at the north end; four to five cold (or hot) frames on the east edge of the garden; and a well (based on preliminary archeological investigations, 1991) located near the south end of the garden. Although this layout provides some idea of the overall organization of the garden, due to the small scale of the drawing, it is likely that the 1844 "Line of Fire Map" excluded more detailed information, such as the location and character of paths and planting beds.

Richard Covington's 1855 sketch lends some detail to the larger grid pattern of the garden. For example, there are numerous deciduous trees, probably fruit trees, arranged in a regular pattern, and a large bed in the northwest corner of the garden, also depicted in the 1844 "Line of Fire Map", appears to contain a variety of trees, including several conifers, possibly Douglas-fir trees. The long north-south bed on the west edge of the garden appears to be densely planted with small trees, again, probably fruit trees. The east side of the garden contains fewer trees and there are more beds indicated than on the 1844 "Line of Fire Map".

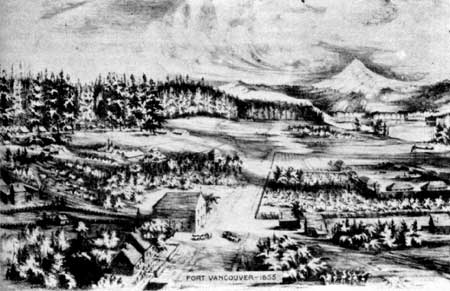

|

| 1855 illustration of the HBC Fort Vancouver and Camp Vancouver (U S. Army) by Richard Covington showing garden details. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo file. |

In 1846, documentation indicates the garden was reduced when the west edge of the garden was aligned with the west stockade wall rather than extending beyond it (as in 1844). The size and location of the garden in 1846 would be maintained through the departure of the Company in 1860, although details of the layout and type of planting undertaken during this period is unknown. The 1860 Boundary Commission photo shows a number of fruit trees planted in a loose grid pattern along the northeast corner of the garden. It is not known when these trees were planted or what kind of fruit trees they were. [10] The 1854 army list of Company's improvements includes eighty fruit trees that appear to have been located mainly in the garden; perhaps these were the trees in the 1860 photo.

|

| 1860 British Boundary Commission photograph. Vi north from the northeast come of the HBC garden towards the U.S. Army's Camp Vancouver. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo. |

Little is known about the gardening techniques employed in the garden. It is generally understood that Chief Factor McLoughlin ultimately oversaw, if not directly participated in, the design and care of the garden, but no details of his gardening expertise have been discovered to date. Books owned by McLoughlin, such as John Claudius Loudon's Encyclopedia of Agriculture, may offer some insight into common agricultural practices of the time. While McLoughlin appears to have been actively involved in the garden, the principal gardener, William Bruce, also played a major role in its development and care.

William Bruce, originally from Scotland, was listed as a laborer in 1826 for Fort Vancouver and was first mentioned as being the principal gardener there in 1833. He returned briefly to England in October of 1838 at the end of his first term, but "begged" McLoughlin to reemploy him. McLoughlin agreed but first sent Bruce to the gardens of Chiswick House, according to Charles Wilkes, "to get a little more knowledge of his duties". After spending a few days at Chiswick, Bruce set sail for Fort Vancouver, arriving in September of 1839, where he served as gardener until his death in 1849. Wilkes' comparisons of Fort Vancouver's garden to Chiswick, and plants sent to Fort Vancouver by Joseph Paxton, Chiswick's gardener, suggest a high level of expertise was employed in the development and maintenance of the garden. Chiswick was the seat of the Duke of Devonshire and at the time his garden, operated by the Horticultural Society of London, was one of the most important gardens in England. Joseph Paxton was a noted horticulturalist and publisher of two horticulture magazines.

Agricultural tools were both imported and "country made". British suppliers included Bryan Corcoran & Co.; John Davis; Ransomes & Sims; and Mary & Thomas Wedlake. The garden probably used similar tools to those used in other agricultural activities, presumably with the exception of tools used for large-scale grain cultivation. Agricultural tools listed in Company inventories and likely to have been used for the garden are listed in Appendix C.

The garden at Fort Vancouver served several purposes. First and foremost was creating a supply of fresh produce for the Company employees. Most of the produce was served at the mess table for officers, clerks, and selected guests, in addition to selected employees and visitors in the Big House kitchen. The second purpose of the garden was to serve as a social outing and pleasure ground where special guests were invited by Chief Factor McLoughlin to walk in the garden and sample the garden fares. Third, the garden provided a supply of plants for visitors planning to settle the region, seeds for local Indians to cultivate in gardens near their camps, and seeds and cuttings for generating more plants for the garden and orchard. Producing a ready supply of seeds and plants was essential for maintaining a self-reliant post and was critical to settlers who had no other local sources to draw upon during this time. In addition to collecting seeds and plants from the garden, a portion of the garden was set aside as a nursery. The location of the nursery is unknown.

There are numerous references to the types of plants (common names) grown at Fort Vancouver, however, detailed lists of plant varieties are limited. Fruit trees included pears, nectarines, apricots, cherries, plums, figs, lemons, oranges, citrons, and pomegranates. Vegetables included carrots, turnips, cabbage, potatoes, squashes, parsnips, cucumber, peas, tomatoes, and beets. Fruits and flowers included strawberries, gooseberries, musk and water melon, raspberries, currants, quinces, grapes, roses, and dahlias.

A list of plants grown in the garden based on visitor and Company employee descriptions and HBC records is provided in Appendix D. Documentation on plant varieties specifically grown at Fort Vancouver are limited, therefore, available seed lists purchased for the Columbia Department, in general, and for York Factory, have been included to lend some understanding of the probable vegetable, fruit, and flower species grown at Fort Vancouver.

Orchard

The history of the orchard as a distinct unit (separate from the garden) is complicated because many of the records and descriptions of the orchard are intermixed with the history of the garden. This is due largely to the fact that the first fruit trees established at Fort Vancouver were planted in the garden (and continued to exist in the garden throughout its development), and most visitors did not distinguish between the garden and orchard in their observations. Fruit trees were first observed in 1828 by American fur trader Jedediah Smith who reported seeing a fine garden with small apple trees and vines, which suggests they were planted at least by spring of 1828, if not sooner. The date of his observation correlates well with the multiple variations of a story of a gentleman or gentlemen (Lt. Aemilius Simpson was the featured gentleman in several versions), who arrived from London carrying apple and grape seeds in a vest pocket, which were probably planted in 1827 at Fort Vancouver. The seeds were reportedly first planted in "little" boxes which were placed in the store (warehouse) and covered with glass until the trees were large enough to plant outside. [11]

Since the location of the garden referred to in 1828 is unknown, it is also not known if these apple trees were planted in or relocated to the 1828-29 stockade garden. Wherever their location, by 1829 it is known that three peach trees were planted in the 1828-29 stockade garden, and from that time on, a wide variety of fruit trees, including pear, apricot, cherry, plum, fig, lemon, orange, citron, and pomegranate trees, were observed in the garden. A list of fruit trees grown in the garden/orchard can be found in Appendix E.

The development of the orchard as a distinct feature, separate from the garden, can only be approximated from existing research. Documentation suggests the orchard became distinct from the garden between 1836 and 1839, although it was not until 1844, the date of the first map of the site, that the orchard, in relation to the garden, was illustrated for the first time.

The area planted with trees on the 1844 "Line of Fire Map" is approximately 380-400 by 600 feet, or 5.2 acres. This area extends from Upper Mill Road south to a line parallel to the stockade's north wall, and east from a point near the river road to the west edge of the garden (120' feet west of the bastion), and continues north back to Upper Mill Road. Some illustrations from the 1850s suggest the area south of the stockade may have been planted as an orchard in the 1850s. However, as of 1844, the orchard was confined to the area northwest of the stockade.

The orchard was enclosed by a fence that extended beyond the planted area. The fence extended west from the southwest corner of the stockade along Lower Mill Road to the river road where it continued north to Upper Mill Road, then east to the west edge of the garden.

As with the garden, and Fort Vancouver as a whole, after 1844/46 the orchard declined in size and upkeep. An extensive fire in September 1844 had a dramatic affect on the orchard, burning the north half of the orchard, the fence along Upper Mill Road, and the upper portion of the fence separating the garden and orchard. The fence was rebuilt but it appears that the trees were never replanted.

Detailed information about the orchard, such as tree spacing, the number of trees, and types of trees planted, is vague at best. The only mention of the number of trees was in 1841 when horticulturalist William D. Brackenridge observed four hundred to five hundred apple trees in bearing state. Some confusion arises because Brackenridge did not say these trees were specifically in the orchard, rather that he saw them when McLoughlin ". . . showed me round his gardens. . .". If these trees were confined just to the orchard which was approximately 380-400 by 600 feet, then in order for four hundred to five hundred trees to "fit", the trees would need to be spaced around twenty-two to twenty-four feet on center. The 1846/47 Stanley drawing shows a total of about fifty-two trees in the garden and part of the orchard. The only other specific reference to the number of trees was in 1854 when eighty fruit trees were listed by the U.S. Army as part of the HBC improvements. Research suggests these trees were planted in the garden and not the orchard.

Another approach to estimating the number of trees in the orchard, and the tree spacing is from 1850s illustrations that depict the orchard. While there were some discrepancies, the Covington, Sohon, and Hodges drawings suggested a spacing of about thirty feet on center. This spacing agrees with J.C. Loudon who also recommends in The Encyclopedia of Gardening... that standard trees should be planted thirty to forty feet on center. [12]

With a thirty foot spacing in the 380-400 by 600 foot orchard area, there would be a grid pattern of about fourteen trees along Upper Mill Road and about twenty trees running perpendicular to the road equaling approximately 280 trees. This does not equal the 400-500 apple trees noted by Brackenridge, if his observation was correct, but perhaps the other trees were in the garden.

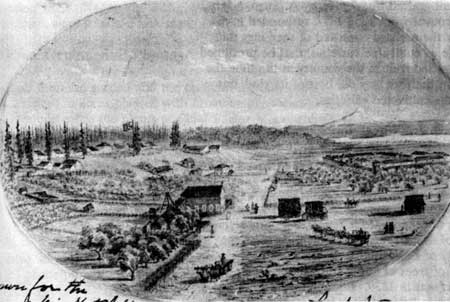

|

| 1855 illustration by Lt. H.C. Hodges (US. Army). View east from Kanaka Village towards the HBC stockade and US. Army Camp Vancouver. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo file. |

The question of what types of fruit trees were in the orchard is also difficult to determine. While most references suggest the orchard was composed of apple trees, or at least a majority were apple trees, there is some indication that there were other fruit trees as well. For example, George Roberts' 1838 Thermometric Register for Fort Vancouver noted apple, pear, and peach trees but not any of the many other varieties of fruit trees known to be growing at Fort Vancouver at that time. It is possible that Roberts, who was in charge of the fort's "Outdoor Work", tended only the orchard and field crops, while others administered the garden (while William Bruce was in England). This might suggest that peaches and pears, in addition to apples, were found in the orchard.

There is also the question of whether the trees were seedlings or grafted, and if they were grated onto standard, semi-dwarf, or dwarf rootstock. Most sources agreed that the trees were seedlings and not grafted. For example, Brackenridge noted the apple trees were ". . . with the exception of a few approved varieties imported from England the whole stock has been raised from Seeds at Vancouver, and to my taste the majority were better adapted for baking than for a dessert. . . ." Likewise George Gibbs noted the apple trees were "natural and not grafted trees". Henry A. Tuzo, a HBC doctor at Fort Vancouver from 1853-1857, responded to a question of whether the orchard consisted of seedlings that were not as valuable as cultivated varieties, that he presumed "... there was no grafted fruit in the country at the time the orchard was laid out; the fruit was the best of its kind, but not so valuable as the cultivated varieties."

While the use of some dwarf trees during the historic period is possible, to date, only one reference to their use has been documented. John Dunn, a appostmaster at the fort from 1836-1838 noted that the apple trees at Fort Vancouver were dwarfs. It is not known if his description is based on personal observation or not, some of his accounts were based on the observations of others. If his report is accurate, the most likely source of dwarf rootstock in the 1830s was the Horticultural Society of London. To date, the only documented arrival of trees of any kind from the Horticultural Society was in 1839. In September, the gardener William Bruce brought back fruit trees from Chiswick "under glass", but this post-dates Dunn's stay and also does not indicate if the trees were grafted or grafted onto dwarf rootstock. [13] Captain Nathaniel J. Wyeth may have been a source for grafted trees. In a 1847 letter, he noted improvements made in 1835 at Fort William on Sauvie Island as follows, "At this post we...planted wheat, corn, potatoes,...grafted & planted apples and other fruits...)." [14] However, the reference to grafted trees, still does not indicate what kind of rootstock (standard, semi-dwarf, or dwarf) was used.

A number of illustrations of Fort Vancouver provide the only other site-specific clues about the character and extent of the trees in the orchard. Based on the height of the trees depicted in the drawings, twelve to twenty-five feet, they appear to be standard or possibly semi-dwarf trees (dwarf trees usually only grow to a height of six to nine feet). [15] Finally, although dwarf fruit trees were common in England and Europe at the time, they were most often recommended for the garden, while standard trees were commonly recommended for the orchard. [16] Until further evidence related to the trees in the Fort Vancouver orchard is discovered, it is probable to assume that during the historic period 1829-1844/46, the majority of apple trees in the orchard, were standard size seedling trees.

Other Ornamental Plants

Other than the garden and the orchard, the only other references to areas planted with ornamental species at Fort Vancouver were the plants at Chief Factor McLoughlin's house. It was noted that the house had a piazza and ballustrade with grape and other vines growing on it, and small flower beds in front. The flower beds were presumably located inside the white picket fences in front of the house, on both sides of the entrance. In the 1860 Boundary Commission photo, grape vines are growing from the base of the house, climbing up the top railing and continuing up to the roof, supported by vertical poles along the front of the porch, and arched poles over the front entrance and at each end of the porch.

Vegetation Summary and Analysis

Vegetation is a critical component of the Fort Vancouver landscape because of the prominent role agricultural and subsistence activities played in the fort's success and influence in the Pacific Northwest. The cultivated fields, garden, orchard and livestock pastures were all significant landscape features.

Today there are no known vegetative remnants or features introduced by the Hudson's Bay Company, within the National Historic Site boundary. An interpretive orchard, planted in 1962, exists on the site of the historic garden. There is also an interpretive period garden located northeast of the stockade on the site of what was historically a cultivated field.

The only documented vegetation existing from the HBC period includes two Douglas-fir trees at the east end of the parade ground, and the apple tree in the city's Historic Apple Tree Park. Two large Oregon oak trees on the parade ground may date from the 1850s, and a pear tree located north of East Fifth Street appears to be an old variety, although its location does not correspond to the known development by the HBC.

While, to date, no other vegetation dating from the historic period exists in the park today, the landscape character of some areas surrounding the stockade is still indicative of the vegetation associated with the historic period. For example, during the HBC period, the undeveloped area north of Upper Mill Road consisted of Oregon oaks and Douglas-fir trees scattered across a natural prairie. Today, the Douglas-fir and Oregon oak trees scattered across the manicured lawn of the parade ground retain the general character of the historic period. Several of the trees on the parade ground date from early in Vancouver Barracks' history. Clumps of Oregon oaks that are spread across the Vancouver Barracks portion of the park, were also common in this area during the HBC and Vancouver Barracks periods as part of the oak savannah transition zone between the conifer forest and the plain. [17]

The vegetation along the river historically consisted of native riparian trees and shrubs. Today, the majority of the waterfront also consists of riparian vegetation, masses of black cottonwoods, willows, and alders. The open fields north of Highway 14 are similar to the open-space character of the pasture and fields of the HBC period. However, the overall visual character of the area lacks historic detail and diversity, due to the lack of crops and the associated grids and patterns created by fields and rows of crops. The structures and features associated with the Pearson Airpark development significantly impact the open character of the historic cultivated fields.

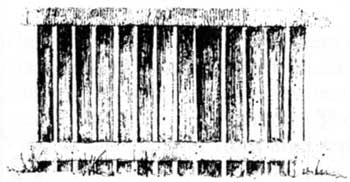

STRUCTURES

Information about building styles and construction techniques is generally derived from research and knowledge about the buildings in the stockade and some from structures in Kanaka Village. Two main building styles were used at Fort Vancouver, Canadian style and frame construction. Buildings constructed in the Canadian style were known as either "post-on-the-sill" or "pile-in-the-ground", depending on their foundation construction. Post-on-the-sill foundations consisted of sills resting on wooden blocks with walls created by placing grooved uprights on the sills, six to ten feet apart and fitting sawed (or hewn) horizontal timbers onto the grooves. The roofs consisted of plates, placed on top of the uprights, with rafters attached to them. Roofs were either covered the with one foot wide, by one inch thick sawed boards or shingles. For pile-in-the-ground foundations, the framing posts extended from the walls into prepared holes.

Frame structures apparently existed at the fort but seem to have been the exception. Also, they were probably not light "balloon frame" buildings, but instead buildings with superstructures similar to Canadian style, with heavy timbers for sills, upright posts, and plates. They differed from Canadian style by using nailed board siding or slab siding.

Squared timber and log houses noted in historic references also probably used the same construction technique, but differed in their treatment of wall material; using hand hewn (or sawed) square timbers, or unshaped, round timbers. [18]

Stockade and vicinity

Stockade

The stockade itself was constructed of closely fitted vertical logs (mainly Douglas-fir) from five to thirteen inches in diameter, with the larger posts used in the corners. Around the inside stockade wall, horizontal cross pieces, pegged or notched into the logs, lay about four feet from the top. The cross pieces were about thirteen feet long and were mortised at the ends into larger posts called "king posts".

The height of the stockade until 1845 was estimated by visitors to be between eighteen and twenty-five feet above the ground. After 1845, estimates ranged between twelve to twenty feet, with fifteen feet cited most frequently. By 1841, when the stockade dimensions were 732-734 feet east-west, by 318 feet north-south, three gates existed; two on the south side and one on the north. The north gate was about 212 feet from the stockade's northeast corner and probably measured twelve feet wide. The southeast gate was 10.75 feet wide, while the southwest (original) gate, which was 164.5 feet east of the southwest corner, was thirteen feet wide.

Structures within the Stockade

Most of buildings inside the stockade were built in the Canadian style with "post-on-the-sill" foundations. Until the mid-1840s, the roofs were covered with one-foot-wide, by one-inch-thick sawed boards. By 1845-46, most of these boards were replaced by shingles. Roofs appeared to have been simple gable roofs early in the stockade's history, but by 1846 eight of the principal buildings had hip roofs.

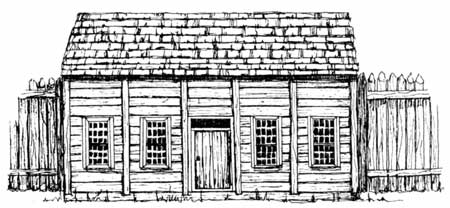

|

| The third bakery, located in the stockade interior, was constructed in Canadian Style, a style typical of Fort Vancouver and the fur-trading industry. |

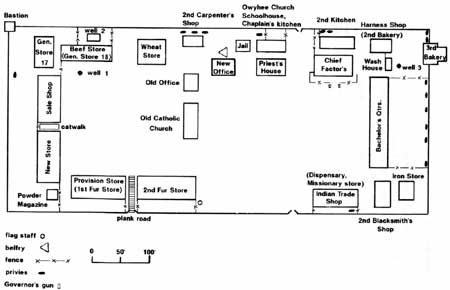

In ca. 1844-46, there were twenty-five major structures in the stockade. Generally, the buildings were clustered into two courtyards, with storehouses on the west side and residences, administration, and service buildings on the east side. The west courtyard consisted of storehouses lining the north, west and south sides of the courtyard, with the old office and the old Catholic church located on the east side of the courtyard. In the northwest corner of the stockade was a bastion, constructed in 1845. The east courtyard contained residences and associated structures. Residences included the Chief Factor's House and kitchen, the Priest's house, and bachelor's quarters, and wash house. Administrative buildings included the new office and the jail, while support buildings or workshops included the Indian trade shop (and dispensary), bake house, harness shop, and blacksmith's shop. Buildings with social functions included the Owyhee church and schoolhouse. Storehouses included the iron store. Due to the large amount of detailed information about stockade buildings already included in other documents, they will not be described separately in this report.

|

| Structures and features in the Fort Vancouver stockade at the height of the site's development in 1844/46. (click on image for a enlargement in a new window) |

Detailed information about the exterior appearance and finish of structures is scarce. The Chief Factor's House, Priest's house, new office, European sales shop, and one other building, were weatherboarded and it appears that some buildings were white-washed. White-washed buildings included the Chief Factor's House, the new office, wheat store/granary and possibly the bake house. It is uncertain if the remainder of the buildings were white-washed or not. [19]

|

| 1860 British Boundary Commission photograph showing structures in the stockade including, from left right, the Priest's house, Chief Factor's house, and Bachelors quarters. Note small-scale features such as the third belfry and the wood plank road. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo file. |

In addition to the wheat store, there were several minor buildings within the stockade that were of frame construction rather than Canadian style construction. They were described by an 1841 visitor as being built of puncheons (split logs or heavy slabs) set in a frame. [20] A covered wooden catwalk connecting the upper floors of the new store and the sale shop appears to have existed between 1829 and 1860. The powder magazine was constructed of bricks imported from England.

Outlying structures

Several buildings were located immediately outside the southeast corner of the stockade. The number and location of buildings varies on historic illustrations; however, according to two reliable drawings, there are three gable-roof buildings sited parallel to the stockade wall. The closest building to the stockade is labeled "Cooper's shed" and was listed on the 1846/47 inventory as being seventy by thirty feet. The two eastern buildings may have been dwellings. Archaeologcal excavations have uncovered several structures in the area, including a building tentatively identified as the cooper's shed, a privy, a pre-1841 building within the pre-1841-44 expanded stockade wall, and possibly other structures outside the wall. [21]

There were also several structures related to agricultural operations in the vicinity of the stockade. Most of these structures, except the barn complex, were located south of Upper Mill Road, east of the river road, and along the river. These buildings are as follows:

Summerhouse