|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1309

The Geologic Story of Isle Royale National Park |

WHAT HAPPENED WHEN?

The geologic story of Isle Royale as presented up to this point has been largely a description of the geology as we see it now. But how did it get this way? And when? The search for answers to these questions involves considerable interpretation of geologic observations made on Isle Royale and in the Lake Superior region, together with numerous deductions based upon our accumulated geologic knowledge. Some parts of the geologic history can be deciphered in considerable detail, and other parts only incompletely because the geologic data are very spotty. The first step toward the answers is to develop a time framework within which to reconstruct events in the geologic past.

TIME AS A GEOLOGIC CONCEPT

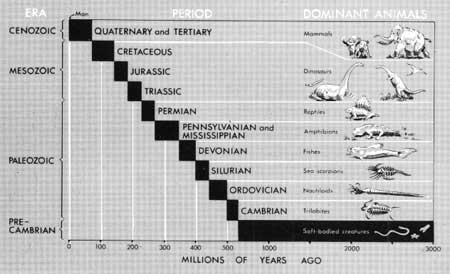

A relative time scale, useful throughout the world, has been developed by dividing the last approximately 570 million years of geologic time into periods. The periods, which began with the Cambrian and end with the Quaternary, are recognized largely from the fossil record (fig. 40). Rocks of the Cambrian Period contain the earliest evidence of complex forms of life, which slowly evolved through the subsequent periods into the life of the modern world. The presence of distinctive fossils in various periods permits the correlation of rocks of similar age. However, the near absence of fossils in Precambrian rocks—those older than 570 million years—severely limits the use of fossils for the relative dating of the Precambrian rocks, rocks which cover more than 80 percent of geologic time. The rocks on Isle Royale are unfossiliferous and of Precambrian age, and it is with this poorly classified segment of geologic time that we are mostly concerned.

|

| GEOLOGIC TIME CHART showing major divisions. (Fig. 40) |

Fortunately, a means for measuring geologic time without fossils has been developed from the long-known natural process of radioactive decay of certain elements. From such radiometric age determinations, many rocks can now be assigned ages in years, which for Precambrian rocks, in the near absence of fossils, are virtually the only means for long-range correlations.

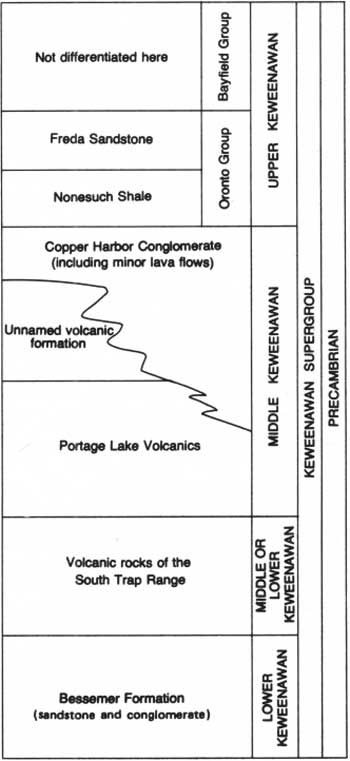

The uppermost, or youngest, Precambrian rocks in the Lake Superior region consist of a thick sequence of volcanic and sedimentary rocks. This sequence has been named the Keweenawan Supergroup because many of the formations that make it up were first described on the Keweenaw Peninsula and adjacent parts of Michigan and Wisconsin. The period of time during which the Keweenawan rocks were deposited can be referred to informally as Keweenawan time, recognizing that the term has usefulness only in the Lake Superior region where the Keweenawan rocks themselves occur. The Keweenawan Supergroup has been informally divided into lower, middle, and upper parts; formations exposed on Isle Royale, the Portage Lake Volcanics and the Copper Harbor Conglomerate, are assigned to the middle Keweenawan (fig. 41). We do not have sufficient data to determine the bounds of Keweenawan time, but radiometric age determinations indicate ages in the general range of 1,120-1,140 million years ago for the Keweenawan volcanic rocks. It is from this point in the enormously distant past that we begin to unravel the geologic history of Isle Royale.

|

| KEWEENAWAN SUPERGROUP—classification in Michigan. (Fig. 41) |

WHAT WAS THERE BEFORE—THE PRE-KEWEENAWAN

Rocks of Keweenawan age, as old as they are, rest upon still older Precambrian rocks that are strikingly different. The older, or basement, rocks are of many varieties, ranging from granite and other intrusive igneous rocks to volcanic and sedimentary rocks, and cover a wide range in age. They usually are both more highly metamorphosed, or altered from their original state, and more strongly deformed than rocks of the Keweenawan sequence. Basement rocks are not exposed on Isle Royale, but they are sufficiently well exposed in areas both north and south of Lake Superior for their nature to be studied and their relationship to the overlying Keweenawan sequence to be determined.

The history of the pre-Keweenawan rocks is extremely complex, as might be expected from the wide range in rocks and age; however, prior to the time the Keweenawan rocks were deposited, much of what is now the Lake Superior region had been reduced to an area of fairly low relief, and shallow seas covered large parts of it. A thick sequence of marine sedimentary and volcanic rocks was then formed in those seas. In addition to impure sandstone and shale, chemically precipitated sediments were deposited, including dolomite and the iron-rich rocks that were later to make the Lake Superior district world famous as a producer of iron ore. The material forming the pre-Keweenawan volcanic rocks was erupted under water, where quick quenching of the lava caused it to congeal in irregular-shaped globular or ellipsoidal masses that accumulated one upon the other at the bottom of the sea (fig. 42). These volcanic rocks are thus quite different from the uniformly layered widespread sequence of Keweenawan flood basalts.

|

| ELLIPSOIDAL STRUCTURES indicative of extrusion of lava under water, found in Precambrian volcanic rock from northern Michigan. (Fig. 42). |

Toward the close of pre-Keweenawan time, the rocks present were folded, deformed, and eroded, quite drastically in some areas and only slightly in others, and so the material forming the overlying Keweenawan volcanic and sedimentary rocks was laid down on the edges of the older beds in some localities.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1309/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006