|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1309

The Geologic Story of Isle Royale National Park |

WHAT HAPPENED WHEN?

(continued)

THE ROCKS OF ISLE ROYALE—THE KEWEENAWAN

The lowermost Keweenawan strata, which are not present on Isle Royale, consist of a relatively thin sequence of sedimentary rocks, chiefly conglomerate and sandstone, that lie on the pre-Keweenawan rocks. They have been interpreted as shallow-water, near-shore deposits and are exposed in only a few localities along the perimeter of the area of Keweenawan outcrops around the margins of the Lake Superior basin. The lowermost few of the Keweenawan lava flows above these sedimentary rocks contain ellipsoidal structures typical of those formed when lava is erupted into a body of water. Such structures are found only near the base of the lava sequence, however, and we conclude that the first few of the flood basalt flows were erupted into a shallow body of water, which was soon filled or disappeared for one reason or another, and that all later flows were on virtually dry land. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the sedimentary rocks interbedded with the lava flows show characteristics typical of those formed in streams rather than in lakes or oceans.

The source of the lavas appears to have been along the axis of an arc-shaped trough or system of fissures generally following the center of present-day Lake Superior. The system was actually much more extensive, however, extending southwest at least as far as Kansas and southeast into the southern peninsula of Michigan, a total distance of over 1,000 miles. Great volumes of lava were erupted from fissures near the axis of the trough and spread laterally and rapidly toward both margins of the trough, finally ponding and cooling in place to form vast sheets covering thousands of square miles. The Portage Lake Volcanics, as exposed on the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale, represent roughly the upper half of this volcanic pile (fig. 41).

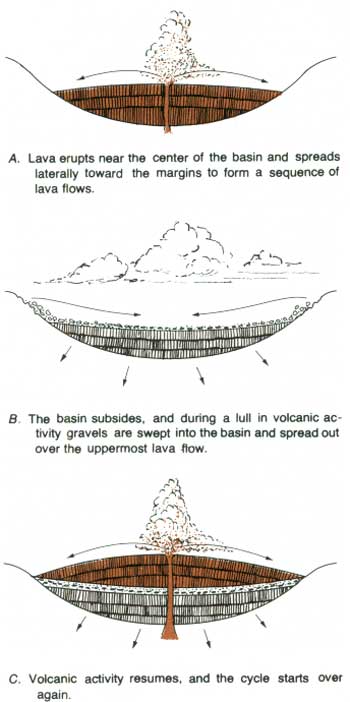

The material forming the sedimentary rocks that are interbedded with the lava flows of the Portage Lake Volcanics and that are in the Copper Harbor Conglomerate and other Keweenawan formations above the lava sequence was transported by streams into the trough or basin from highlands around its margins. This evidence for inward flow of streams, contrasted with evidence that the lavas flowed toward the margins of the basin, shows that there were, at times, reversals of the prevailing slope over large areas and leads to the concept of a basin subsididing as it was being filled (fig. 43). The surfaces of the lava flows were horizontal or sloped gently toward the margins of the basin as long as filling by lava kept pace with downwarping. When extrusion of the lava was interrupted, however, continued down-warping produced inward slopes that permitted sedimentary debris to be swept into the basin. Finally, with the gradual demise of volcanic activity, continued subsidence permitted the accumulation of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate and younger Keweenawan deposits to form a thick sedimentary sequence above the volcanic rocks in the basin.

|

| FLOOD BASALTS AND SEDIMENTS showing the process of interbedding. (Fig. 43) |

Sandstone of latest Keweenawan or earliest Cambrian age is exposed along much of the shore of the southeastern part of Lake Superior and extends westward to the Keweenaw Peninsula. The basin may have been largely filled by this sandstone, together with similar sandstone exposed in the southwestern part of the basin (fig. 39).

The gross synclinal form of the Keweenawan basin resulted from subsidence coincident with filling of the basin rather than later folding by squeezing. However, Keweenawan strata near the margins of the basin, as on the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale, were subsequently steepened by upward movement on major faults, the Keweenaw fault and the Isle Royale fault, thus accentuating the synclinal structure (fig. 38).

THE MISSING CHAPTERS

It is somewhat disconcerting that we can reconstruct so much of what happened during the Precambrian and so little of the geologic history of the Lake Superior region during the last 570 million years, including most of the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic Eras. But this is the situation, for erosion has removed most of the critical evidence regarding that period of time. And, of course, much of the area is concealed by Lake Superior itself.

We do know, nevertheless, that the rocks of the Lake Superior region constitute the southermost part of an area known as the Canadian Shield—an area of predominantly Precambrian rock and one that for the most part has been relatively stable geologically since the Precambrian (fig. 44). Beginning in Late Cambrian time, however, the so-called Michigan Basin, centered on what is now the southern peninsula of Michigan, began to subside, and a thick sequence of Paleozoic rock accumulated in the invading sea. Lower Paleozoic rocks at the margin of this basin extend up onto the shield near the southeast shore of Lake Superior. A few remnants of lower Paleozoic dolomite occur as far west as the base of the Keweenaw Peninsula; they are very thin and were probably deposited very close to the outer margin of the Michigan Basin.

|

| THE CANADIAN SHIELD (stippled area)—predominantly Precambrian rocks. (Fig. 44) |

We also know that lower Paleozoic rocks are present in a fairly extensive area centered on Hudson Bay. They include various types of rocks of shallow marine origin and in the vicinity of James Bay are locally overlain by non-marine Cretaceous sedimentary rocks that include coal. Remnants of lower Paleozoic strata at a few other scattered localities on the Canadian Shield indicate that such strata were once more extensive than now, but how extensive is unknown. It is possible that they covered the entire shield, but we have no direct evidence that such rocks were ever present in the vicinity of Isle Royale.

Much of the Canadian Shield probably had been eroded to a relatively flat surface prior to the deposition of the lower Paleozoic strata. It remained so during the deposition and the subsequent erosion of much of those strata, right up to the Pleistocene Epoch and the onset of glaciation. Sometime after the deposition of the Jacobsville Sandstone of Precambrian or Cambrian age, however, movement on the Keweenaw fault thrust the Portage Lake Volcanics up over the Jacobsville Sandstone on the Keweenaw Peninsula. Presumably at about the same time, thrusting on the Isle Royale fault left the volcanic rocks of Isle Royale standing as an elongate ridge surrounded by softer sedimentary rocks. With this last disturbance the present geologic structure of the Lake Superior region was established, and little has happened since except for erosion by both water and ice. A broad river valley probably developed in the present site of Lake Superior, as well as in the sites of the other Great Lakes, for all are located in belts of rocks less resistant to erosion than their bounding areas. The gross features of the preglacial landscape probably exerted a major influence on the direction of ice movement as successive lobes of glacial ice invaded the region during the Pleistocene and moved through the ancestral "Lake Superior valley."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1309/sec5a.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006