|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1673

Selected Caves and Lava Tube Systems in and near Lava Beds National Monument, California |

CAVES EASILY ACCESSIBLE FROM CAVE LOOP ROAD

(continued)

Catacombs Cave

Catacombs Cave (map 3, pl. 1) is popular among monument visitors; J.D. Howard was the first to record notes on exploration of this complicated and interesting network of underground passages. Visitors who are unable or unwilling to venture far underground can find excellent lavacicles and dripstone exposed on the ceiling and walls of several branching passages within 200 ft of its entrance. These features, plus a floor of ropy pahoehoe, are nicely displayed in the small dead-end tube called The Bedroom, which is easily reached by a 150 ft traverse that takes two left turns and then two right turns from the entrance. Those who wish to spend more time underground and observe a wide variety of lava-tube features will enjoy the area around The Bathtub. It is reached by an easy traverse of nearly 720 ft down the main passage, where a short flight of stairs leads up to The Bathtub.

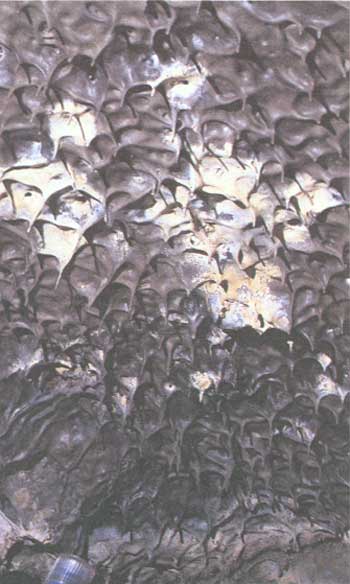

Adventurous persons who enjoy long crawls over rough-surfaced pahoehoe (fig. 24), while simultaneously trying to avoid the thrust of sharp lavacicles into their backs, will find their mettle tested by a long underground trip to Cleopatras Grave (fig. 13) via Howards Hole.

|

| Figure 24. Rough-surfaced flow almost filled the complex downstream part of Catacombs Cave (see fig. 14 and map 3, pl. 1), leaving only a low crawlspace for explorers. Note false gold cave deposits on lavacicle-studded ceiling. |

And finally, people interested in the hydraulics of a complicated near-surface lava-tube system will find the pattern of tubes, complicated breakdowns, lava falls, drains, and cascades near The Bathtub to be particularly interesting. Similar features, as well as balconies and rafted blocks, are found farther downstream near Howards Hole.

The overall length of the accessible area of the Catacombs system is 2,000 ft but rarely is it as wide as 250 ft. Yet, because of the abrupt turns, the interconnected passages, small complicated cascades, lava falls, interchanges that join passages together at different levels, and the numerous short distributaries that are nearly filled with lava, the total length of accessible passage is more than 7,500 ft. This very complicated system of irregularly branching tubes of different sizes, lengths, and trends (see map 3, pl. 1) makes Howard's name, the "Catacombs," particularly apt.

Most of the passages become inaccessible downstream because lava has ponded to within inches of their roofs, whereas some are inaccessible due to collapse. Therefore the above figure of over 7,500 ft represents only a part of the total tube system in operation during active volcanism.

Entrance to the Catacombs is on a well-marked trail that starts at the Catacombs parking lot beside Cave Loop Road. The trail leads east into and across a large collapse trench, which is a part of the line of major breakdowns coursing through the Cave Loop area. Beyond the climb out of the trench the trail continues east then southeast for 160 ft and then drops into the 140-ft-long and 120-ft-wide Catacombs Basin (map 3, pl. 1). The trail skirts an apron of collapse blocks for 80 ft and then turns due east and enters Catacombs Cave.

Former Lava Lake in Catacombs Basin

During part of the period of volcanism, Catacombs Basin was apparently filled by a lake of molten lava. This lake acted as a holding reservoir from which lava flowed into the Catacombs tubes. The lava came from the Paradise Alleys tubes, which branch from the main breakdown channel 650 ft farther up stream at the head of Ovis Cave (map 4, pl. 2). The Paradise Alleys-Catacombs lava-tube system formed a moderate-sized distributary system from this main feeder; the Labyrinth network of caves (map 2, pl. 1) was a larger distributary system on the opposite (northwest) side of the main feeder tube.

At times the volume of the lava in Catacombs Basin exceeded the capacity of the earliest Catacombs lava tubes to transmit lava as fast as it was supplied. Then the lava spilled over onto slightly older flows and, in parts of the area, welded to the flow beneath. Both the older and overlying younger flows developed lava tubes, and connectors certainly developed between tubes on different levels of approximately the same age.

During the waning stages of volcanism enough capacity had developed from increasing numbers of interconnected passages in the Catacombs system, and so the total volume of lava delivered into the holding reservoir could be transmitted. From then on the basin seldom overflowed. The very latest overspills from Catacombs Basin developed four short lava lobes, which are shown on the map. Two of them spread northwest and were later cut off and dropped into the deep collapse trench just south of Crystal Cave. Two of these four lobes had started to form lava tubes within them before they congealed.

With these generalized preliminary remarks to sharpen observation and perception, one can now proceed underground (with map!) and observe the details.

Features Between The Bedroom and The Bathtub

A curious feature of the Catacombs tube system is that it consists not of a single lava tube with neatly branching distributaries, but it instead consists of two, and in places three or more, parallel tubes at slightly different levels and with several interchanges between them. A network of three main tubes developed at the head of the Catacombs tubes long before the last overspills from the Catacombs Basin. Access by trail to the Catacombs is through the southeastern-most of these three tubes. At the Asparagus Patch, downstream 80 ft from the entrance, this tube turns abruptly to the north, and then, 50 ft farther downstream, it is joined by the middle tube of this threefold network. Upstream in this middle tube, one finds another crossover, some 30 ft long, connecting to a section of the third tube. From here, only 80 ft of this northwestern tube is accessible. Upstream it is cut off by collapse breccia along the north wall of the former lava lake. It ends in a curious dead-end feature named The Bedroom. This rectangular room has near-vertical walls completely sealed over with dripstone and a roof covered with lavacicles (fig. 25). The northwest end of The Bedroom is a solid wall of dripstone—its appearance seems to negate the idea that this tube might once have extended farther in that direction. Yet, 45 ft northeast of this walled-in end of The Bedroom, a lava tube with exactly the same trend is present (map 3, pl. 1). Upstream, toward The Bedroom, this tube is filled to its roof with blocks of collapse breccia that are almost completely penetrated and sealed in by lava; downstream the tube is open with a floor of frothy pahoehoe in which are embedded many rafted blocks of collapse material. A little farther downstream this tube is again partly blocked by a more recent roof collapse, which occurred after volcanism had ceased and the tube had drained.

|

| Figure 25. Shark-tooth-shaped lavacicles on ceiling of Catacombs Cave (see fig. 14 and map 3, pl. 1). End of flashlight at lower left for scale. |

Downstream through this network of tubes is a point at the northeast end of Applegate Avenue where the three components of the tube system merge into one large tube 40 ft wide. In another 50 ft, however, this large tube, The Lower Chamber, turns sharply to the north and immediately spawns two branches from its east side. The two branches unite again downstream but continue to flow along near-parallel courses with occasional pillars such as the Wine Cask between them. Additional subdivision is present still farther downstream. By the time one reaches The Bathtub, a northeast-southwest section through The Bathtub Drain intersects seven tubes spread over an area 250 ft wide.

The branching tubes are typical of the kind that can develop in either a large, thick flow of basaltic lava or, more likely, a thick succession of flow units rapidly erupted over a sloping surface. A major eruption will build a large lobate ridge elongated downslope, which develops a thick crust by congealing of the lava on the top and sides of the flow. As lava is fed into the still molten interior of the flow, it begins to break out through cracks in the front and sides of the partly solidified flow, forming definite underground tubes filled with traveling lava. As lava continues to pour into and through these developing tubes, complicated anastomosing passages may result. Further complexity also results from distributary tubes that branch off from the central tube plexus toward the margins; these complications multiply if rapidly fed lobes pile up on one another and weld into flow units containing tubes at different levels.

The Bathtub Area

The Bathtub lies at the center of an area that is one of the most complicated and therefore interesting parts of Catacombs Cave (map 3. pl. 1). Within 80 ft of The Bathtub are five lava falls, three lava cascades, one vertical shaft through which lava tumbled, and over a dozen lava tubes of various sizes, several of which intertwine in a complex fashion.

To find The Bathtub, and The Bathtub Drain within it, follow the trail 720 ft downstream from the Catacombs entrance to the bottom of an 8-ft stairway. Climb these stairs to reach the surface of the lava that fills The Bathtub. It is a pool of congealed lava 75 ft long and 25 ft wide, evidently ponded after it had half-filled a large lava tube. The source of the lava, the cause of its ponding, and the places where it spilled out after overfilling The Bathtub are not immediately apparent but can be worked out on further examination. Walk northeast along the Boxing Glove Chamber (away from the stairs) and notice that the roof of the lava tube gets progressively lower, until, 120 ft from the stairs and around a gentle curve to the right, the ceiling of the tube comes down to and passes beneath the ponded lava. Note also that over the last few feet, the ponded lava is bowed up into pahoehoe ropes, showing that in this part of The Bathtub lava was creeping forward at a very slow rate downstream toward the place where the tube disappears beneath the lava fill. A tube as large as this could easily carry away the lava ponded in The Bathtub in a matter of minutes. Evidently the tube somewhere downstream was dammed, perhaps by a roof collapse, until the increasing hydraulic pressure and the lava's rise in elevation caused it to spill over into some nearby underground tube.

Return toward the stairs along the southeast wall of the Boxing Glove Chamber, and about halfway back notice a small tube, partly filled with lava, that exits The Bathtub eastward. Explore this tube and in less than 10 ft you find lava frozen as it spilled over a 9-ft fall into a much larger tube below. At the base of the fall the lava turned abruptly to the right (south) and tumbled into yet another tube 5-6 ft lower. By using the map or, by a tortuous crawl upstream, you will find that this tube passes directly underneath The Bathtub. Moreover, the tube connects directly with the lava in The Bathtub through a vertical hole that forms the lower part of the feature named The Bathtub Drain. This feature, however, is more easily studied from The Bathtub floor above than from its exit into the lower tube. The Bathtub Drain (fig. 26) is a funnel-like depression near the southwest end of The Bathtub. The upper part of the funnel walls reveals how the lava of The Boxing Glove Chamber floor cracked into crescent-shaped blocks and moved slowly down the vertical shaft of the funnel. The more liquid lava and loose blocks dropped through onto the tube floor below. Because of the almost perfect preservation of the cracked Boxing Glove Chamber floor on the upper funnel walls, we reason that The Bathtub Drain did not open until late in the history of The Bathtub after the floor and much of the interior lava was solid or pasty. When The Bathtub filled, most of the excess lava escaped through two other exits: one is the previously described small tube in the east wall; and the other is over a larger lava fall at the southwest end of The Bathtub where the ladder is located. This 8-ft lava fall dropped the lava into a large tube whose level is 5-6 ft above the floor of the tube under The Bathtub Drain (see map 3, pl. 1).

|

| Figure 26. Protective fence prevents visitors from stumbling into The Bathtub Drain (see map 3, pl. 1) formed when lava drained into lower level of Catacombs Cave (see fig. 14). |

Where did the lava come from that entered The Bathtub and ponded within it? Its source was one of the network of tubes upstream to the southwest. The map pattern shows that the source tube is one of the several northeast-trending distributaries common to the Catacombs system. But where, exactly, is the upstream continuation of the Bathtub tube? Congealed lava at the southwest corner of The Bathtub (just southwest of the Pin Cushion, a large fallen block on the edge of the Bathtub Drain funnel) exhibits pahoehoe ropes indicating that this lava was flowing into The Bathtub through an almost completely filled tube. This tube cannot be examined farther upstream because of a clearance of only a few inches between fill and roof, but the top of this flow can be seen from the top of two lava cascades that pour out of the northwest wall of The Igloo, a tube that contains the stairway (map 3, pl. 1). One cascade is 15 ft and the other 50 ft upstream from the base of the stairway. Again, the clearance between ponded lava and ceiling as observed from the top of these cascades is in most places 1 ft or less, but by probing around with a stadia rod, we determined that the tube is at least 8 ft and in some places more than 20 ft wide. Perhaps at one time the tube continued upstream to a junction (now walled off) with the plexus of tubes 250 ft or more upstream. The elevation here is sufficient to have fed lava into The Bathtub.

But there are other possibilities. Only 40 ft southwest of the foot of the stair, access is almost blocked by a huge cave-in of the roof (map 3, pl. 1). This particular pile of collapsed blocks is younger than the volcanism; the blocks fell into an already drained tube. Moreover, an earlier collapse at or near the same spot when the lava tubes were active could easily have blocked this tube and raised the level of the lava upstream; thus the direction of flow through the present lava cascades on the northwest wall was reversed, a process which would cause a large flow into The Bathtub. Later the collapse dam might have been breached and removed to leave the features we see today. Nor is this the only place where a collapse would have brought about this sequence of events. A second large area of collapse breccia is in this same tube, 140 ft downstream from the base of the ladder. That earlier collapses may have occurred at these or other nearby sites is clearly indicated by the abundance of rafted blocks downstream. Accumulations of collapse breccia smoothed over by lava occur downstream in both this tube and in the one beneath The Bathtub Drain.

A close study of the many lava falls, ponded lava tubes, and areas of both pre-lava and post-lava collapse breccia within 200 ft of The Bathtub shows that the general sequence of events outlined for The Bathtub was partly duplicated in many of the other nearby tubes. Most show evidence of ponding and of synchronous or later collapse into other tubes that left balconies or other features indicating an earlier ponding. Many abrupt changes in trend or in elevation of lava tubes are difficult to explain, except by the shunting of lava from one tube into another; the details that can be worked out of such changes in the complex area within 250 ft of The Bathtub are a lesson in lava hydraulics, but we can never know the entire story. Much evidence is not available because of ponding in many lava tubes to their roof and by the transport or impounding of collapse breccias by further flow of lava. Such puzzles abound in the Catacombs; downstream, Howards Hole and Cleopatras Grave are outstanding examples.

Northeastern Part of Catacombs Caves

Downstream 250 ft from The Bathtub the complexity of the Catacombs tube system decreases noticeably. Most of the short tubes filled with lava to their roofs. The complex areas of high ceilings, lava falls, and large roof collapses give way to smaller tubes so filled with lava that in many places they can be traversed only by walking in a doubled-up position or by crawling on one's belly.

From The Bathtub 1,100 ft downstream to where the Catacombs tubes become inaccessible, the lava was carried forward through three nearly parallel tubes with small vertical differences. The direction of all three averages N. 55° E., except in the last 200 ft, where each turns sharply to the north. The simplest of the three is the one on the southeast.

The Southeastern Tube

The southeastern passage is the downstream continuation of the tube at the foot of the stair that gives access to The Bathtub. Within the first 200 ft downstream from The Bathtub, it sends two branches north, each of which extends only a few feet before feeding down into the tube that crosses beneath The Bathtub. It also receives one tributary, the Dollar Passage, from the south. The southeastern tube then continues downstream in an overall N. 55° E. direction for 650 ft without receiving a tributary or creating a distributary. Throughout this distance it is a fairly low tube (from 2 to 6 ft in height), well drained of lava fill in most places, but pooled in others to heights requiring a crawl. The roof, walls, and floor of the tube are intact nearly everywhere. Excellent examples of lavacicles and dripstone abound. The floor varies from normal to frothy (or cauliflower) pahoehoe.

At the downstream end of this stretch the tube widens, subdivides around one pillar, and then unites near two other downstream pillars. The area near the pillars underwent a partial roof unraveling over 25 ft long. Its floor contains a narrow trough 2-3 ft wide that begins 50 ft west of the southernmost pillar. It begins as a lava gutter in the smooth pahoehoe floor. It gradually deepens downstream and 25 ft from its origin dives below the surface of the pahoehoe. From here it evidently continues as a small tube-in-tube beneath the floor and surfaces again (with collapsed top) 40 ft farther downstream. Another 20 ft downstream it is again lost beneath the pile of collapse rubble west of the middle pillar. What is probably the same gutter, but with a different trend, emerges from beneath the collapse pile between the two northern pillars and dives steeply beneath the east wall of the main tube before becoming sealed with lava (map 3, pl. 1).

The Elephants Rump, named by J.D. Howard, is a small downstream extension of the northeasternmost pillar at about waist height. It was smoothly plastered over and rounded off by flowing lava but to appreciate its similarity to an elephant's rump does require a bit of imagination.

Other features near these pillars, in addition to the plunging tube, suggest that the main tube feeds into a lower and larger open tube downstream from the pillars. Downstream from the cascade both ceiling and walls of the tube are irregular in height and trend. Heights of 6-10 ft are common, whereas much of the tube upstream can be traversed only by stooping or crawling. A remnant of an adjacent tube, which contains a lava pool, opens in the east wall of the tube near the cascade, and many alcoves are present on the sides of the tube. This remnant tube also changes direction from N. 70° E. to N. 15° E.

Travel within this irregular, high-ceilinged passageway ends abruptly some 400 ft downstream from the pillars due to pooling of lava so close to the roof that further access is nearly impossible.

Two Northeastern Tubes

Running roughly parallel with the passage just described are two lava tubes intertwining horizontally but mostly separated vertically from one another. The southeastern tube is never more than 100 ft southeast from one of these tubes, and in places may approach so closely that the wall between is not more than 10 ft thick. The rough parallelism of these three tubes exists through a length of over 1,000 ft, and then all three bend northerly and become inaccessible due to lava filling. The features of two northeastern tubes are more diverse than the southeastern tube.

Area near Howards Hole

Howards Hole is an oval-shaped vertical collapse pit 8 ft deep, which connects the two northeastern tubes where they cross each other. Unlike at The Bathtub Drain, collapse at Howards Hole was sudden, violent, and delivered much molten lava into the lower tube immediately after collapse. At the time of collapse the tube upstream from the top of Howards Hole was filled to the roof with lava. Downstream and immediately above Howards Hole, the ceiling rises into a cupola with a shelf of ponded lava just below the cupola ceiling. Within the cupola the molten fill had cooled enough to develop a fairly thick crust across its surface. Solidification had also progressed inward from the walls and floor of the tube. A sudden collapse of the tube floor where it crossed over the highest point in the underlying tube produced an opening (Howards Hole), which immediately drained the ponded lava of the upper tube and cupola into the tube below. A large part of the solidified crust of the ponded lava broke into large pasty blocks, many of which lodged in the upper margins of Howards Hole. Many more dropped through the hole and were rafted downstream. Some blocks that stuck on the upstream side of Howards Hole created a low dam, which formed a small puddle of lava in the upper tube just upstream from the hole. For the next 40 ft downstream, however, much of the solidified upper crust survived the collapse and was left hanging as a spearhead-shaped balcony 5-8 ft above the irregular floor. The floor near Howards Hole is irregular due to accumulation of collapse blocks overrun by lava. Most of these blocks are large chunks from fallen parts of the balcony.

Balconies Near Crossover Between Tubes

The collapse at Howards Hole may have triggered further collapses and abrupt changes downstream. Downstream from Howards Hole the upper tube drained out to the northeast and has a normal pahoehoe floor locally embellished with stretched-out pahoehoe lobes. However, evidence that this tube was once filled to the top is seen in numerous small remnants of balconies near the roof.

Downstream 200 ft from Howards Hole a prominent balcony occupies an area extending 45 ft upstream and 25 ft downstream from a tiny crossover connecting this tube with a lower level. The same sequence of events as at Howards Hole seems to have operated here: ponding in the upper tube nearly to its roof, partial solidification, and then sudden draining through the crossover into the lower tube.

Downstream from this crossover both the upper and lower tube show signs of a later ponding. The lava dumped into the lower tube from Howards Hole and the crossover was quickly carried away, and the lower tube was drained beyond the large pillar 20 ft downstream from the crossover. A short distance from here, however, the lava began to pond, and 90 ft downstream from the crossover it ponded to the roof and thus ended further access within this tube.

Relations in the upper tube are superficially similar. Downstream from the crossover, the tube drained and the floor composed of rafted blocks in frothy pahoehoe formed. Downstream 40 ft pooling began where the tube turns abruptly north, and 135 ft beyond the crossover, the tube is filled to its ceiling.

Second Crossover and Area Near Cleopatras Grave

The upper tube system mentioned in the previous section is not accessible. On the right wall of the tube, 85 ft downstream from the crossover and 50 ft upstream from its filled end, is what appears to be a second crossover. It is entered by climbing over a 4-ft-high sill on the east wall of the tube and then traversing down the crossover tube 40 ft to the east to reach a large pool 50 ft across, ponded very close to the roof. Another tube appears to enter this pool very close to the mouth of the crossover. It could well be the continuation of the lower tube, which pooled to the roof only 50 ft upstream (map 3, pl. 1). From this tube a sticky lobe of pahoehoe was exuded onto the surface on the large lava pool. It can be traced 45 ft to where it merges into the larger lava pool. Both masses of lava were molten, or pasty, at the time they came together.

At the tip of a V-shaped irregularity in the wall of this large pool, two tubes take off downstream. One, headed north, with only 1 ft of clearance, is filled to the roof with lava just downstream. The other, headed in the normal downstream direction, has 3-4 ft of clearance allowing entrance to another 400 ft of branching tubes and lava pools.

This final downstream section is complicated. Downstream 80 ft from its exit out of the large lava pool, the tube widens into a small lava pond. This pond is a drainage divide, because one tube actually heads back to the southwest—in exactly the opposite floor direction from the rest of the tubes in this system. After flowing for 45 ft, lava in this tube tumbled over a 4-ft cascade into an oval pool 18 ft long and 11 ft wide. The west wall of this pool is within a few feet of the large pool described previously but is at a lower level (map 3, pl. 1). From this oval pool a small tube, ponded almost to its roof, appears to exit south but instead may be backflow from the oval pool.

The second, longer tube from the drainage divide takes the more consistent northeastern course. Downstream 15 ft from the divide its lava flowed over a cascade and into a wider area where it subdivided and rejoined around three pillars. There is evidence here of two large roof collapses that were smoothed over and partly carried away by the moving lava. Rafted blocks are abundant in the pahoehoe floor; they dot its surface for another 100 ft until a floor jam closes the tube.

One large rafted block, located a few feet south of the middle pillar, is of special interest. Its exposed surface is rounded and smoothed (fig. 13)—it floated with its upper surface rising a few inches above the molten flood. The surrounding lava festooned its edges with two to four discontinuous pahoehoe ropes that seem to set the block in a frame. J.D. Howard found the exposed rafted block surface with its pahoehoe frame strikingly similar to an Egyptian sarcophagus in shape. Therefore, when he explored this part of the tube in 1914, he named the block Cleopatras Grave.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1673/sec2c.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006