|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

|

Lecompton. Elevation 846 feet. Population 386. Kansas City 51 miles. |

Lecompton (see sheet 2, p. 22) was the capital of Kansas Territory from 1855 to 1861 and was named from D. S. Lecompte, chief justice of the Territory. It was a noted proslavery stronghold and a rival to Lawrence. The "Lecompton constitution," under which the proslavery party wished Kansas to become a State, was drawn up at a constitutional convention called at Lecompton in 1857. This constitution was overwhelmingly defeated by popular vote. Toward the end of the free-soil troubles the Territorial legislature was accustomed to convene in Lecompton and adjourn at once to Lawrence. Those days of political turmoil are happily past, and now Lecompton is a quiet little village.

|

|

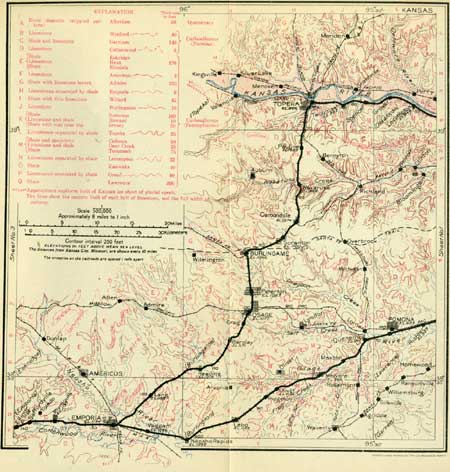

SHEET No. 2 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Between mileposts 38 and 39 the Lecompton limestone crops out in ledges south of the track for some distance, but farther west there wooded slopes which show limestone only at intervals. These slopes continue beyond Grover.

|

Tecumseh. Elevation 862 feet. Population 1,024.* Kansas City 62 miles. Topeka. Elevation 886 feet. Population 43,684. Kansas City 66 miles. |

Tecumseh is on a low terraced slope in a sharp bend of the river. The name is that of a Pawnee chief and means panther. From Tecumseh low river terraces extend westward for nearly a mile, to a point at which they give place to a wide, low flat that extends to Topeka.

Topeka, the State capital, is one of the largest cities in Kansas. It has broad, well-paved streets, with parking and shade trees. Its name is an Omaha Indian word signifying the so-called Indian potato. It is a division point on the Santa Fe Railway and the place of convergence of several branch lines and other railways. The general offices and extensive shops of the Santa Fe system are situated here, and there are many factories and local industries of various kinds, including quarries, brickyards, sand pits, large flour mills, and what is said to be the largest creamery in the world. It was from Topeka that the Santa Fe Co. began building a railway westward in 1869, but it did not reach Santa Fe until 1880.

Topeka was the scene of many riots during the conflict between the abolitionists and the advocates of slavery. Here in 1856 the Free Soil legislature, meeting in opposition to the proslavery legislature, was dispersed by United States troops acting under orders from President Pierce. Five years later, after numerous elections and conflicts, the first State legislature assembled in Topeka.

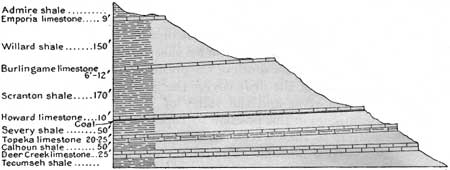

On leaving Topeka1 the train goes nearly south up the valley of Shonganunga Creek and then up one of its branches which heads at the top of the plateau. The ascent is made by a moderate grade, about 125 feet in 5 miles. This plateau is made up of a succession of limestones and shales, shown in figure 3. A few ledges of limestone crop out in the slopes of these valleys. These beds are of late Carboniferous age and slope at a very low angle to the west.

1Mileposts from Topeka to Isleta indicate distance from Atchison.

|

| FIGURE 3.—Section showing succession of rocks in plateau south of Topeka, Kans. |

|

Pauline. Elevation 1,029 feet. Kansas City 72 miles. |

A mile south of Pauline the railway crosses the line of the old high valley through which in glacial time Kansas River flowed across the divide into the valley of Wakarusa Creek. This deflection of the drainage to the south was probably caused by the advance of the great ice sheet southward between Lawrence and Topeka. The ice blocked up the older channel, which was in a general way coincident with that of the present valley but, as explained on page 10, at a higher level, for the old channel across the divide is about 150 feet above the present river. It is marked by a broad depression and especially by deposits of sand and numerous bowlders, some of them very large and easily recognized as having been brought by the ice from regions far to the northwest. The relations of this stream deposit are not well exposed along the railway but are clearly exhibited along the stream and slopes northwest of Pauline station.

At the time when the river passed in this direction it carried the drainage of the west side of the glacial ice from the Dakotas and Nebraska far to the north, and its volume was therefore much greater than at present. It cut a valley toward the east, now occupied by Wakarusa Creek, which, however, has deepened its channel considerably, leaving remnants of the old deposits on the valley sides.

West of Pauline the land rises abruptly in a step due to the outcrop of a hard bed of limestone. This step or ridge is a conspicuous feature for the next 40 miles, the railway skirting the shale slopes and plains at various distances from its foot. The succession of cliffs due to the hardness of limestone and of slopes due to the softness of shale is characteristic of the eastern part of Kansas, especially in the drift-free area south of Kansas River. The rocks consist of alternations of beds of hard limestone, mostly from 5 to 25 feet thick, and of shale, from 25 to 100 feet thick except the Lawrence shale, whose thickness is 200 feet. The beds all dip at a slight angle to the west, and as the country is rolling upland, the limestone beds rise in sloping ledges, usually terminated on the east by cliffs of varying degrees of prominence. These cliffs cross the country from north to south at intervals of 3 to 5 miles, the distance depending on the thickness of the intervening shales and in some places on slight variations in the dip. From a high point in this area can be seen the long westward-sloping steps of limestone and the intervening rolling plains and gentle slopes of shale.

Nearly all of the area is in a high state of cultivation, producing large crops of grains and vegetables. The soil is rich, and a fair proportion of the rainfall, which averages 35 inches a year, comes at the time when crops are growing.

|

Wakarusa. Elevation 948 feet. Kansas City 78 miles. |

A short distance south of Pauline the summit of the divide, which is on the Scranton shale, is reached at an altitude of 1,050 feet; thence there is a down grade to the village of Wakarusa. Here the railway crosses Wakarusa Creek at a point where the stream has cut through the shales to the Topeka limestone, a ledge of which is exposed in the shallow railway cut a few rods north of the station. South of Wakarusa the track rises from the creek valley to a rolling plain, whose altitude is from 1,000 to 1,075 feet. At milepost 64 a 4-foot bed of limestone is crossed by the railway. In the higher portions of the ridges traversed in the next 3 miles there are several cuts in shales, some of which expose thin included beds of limestone.

|

Carbondale. Elevation 1,074 feet. Population 461. Kansas City 84 miles. |

Between Carbondale and Osage there are many small coal mines and numerous abandoned pits and long open cuts. Several of the mines produce a moderate amount of coal for local use and for shipment to various places in eastern Kansas. They are from 10 to 140 feet deep, and at most localities the bed is from 16 to 22 inches thick. Some of the coal has been mined by stripping off the soil and debris and more or less shale along the outcrop, but to the west, as the dip carries the coal deeper, it is reached by shafts. For many years this field was the principal source of supply of fuel for the Santa Fe Railway, and several of the mines were worked by the railway company until other sources of coal were developed. In 1893 and 1894 the annual output exceeded 200,000 tons. The coal1 is bituminous, and although it is not all of high quality this thin bed has been worked with considerable profit. It is known to extend to Lebo and Neosho Rapids, and it is only about 250 feet deep at Emporia.

1Coal consists of carbonaceous material, originally trees and other plants of various kinds, that accumulated in swamps and was finally covered by mud. At the time when such material accumulated in this region it was an area of widespread swamps and morasses with rank vegetation. Later it was covered by the sea, in which were deposited the materials now represented by the limestone and shale. The coal bed is only a few feet below the Howard limestone, which is therefore a guide to the location of the coal. The limestone and shale in this region are of the same age (Carboniferous) as the rocks which contain the great deposits of coal in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Tennessee, and Alabama. Here, however, deeper water prevailed for much of the time and conditions favorable to the accumulation of coal were relatively transient and local.

About the coal mines from Carbondale to Osage are heaps of gray shale excavated in sinking shafts and extending the coal chambers. In places where this debris has contained considerable coal waste it has been ignited at times by spontaneous combustion and the heat has given it a bright-red color, which makes the piles conspicuous. The Howard limestone is traversed a short distance north of milepost 70, on the descent to Hundred and Ten Mile Creek, which is crossed 1 mile north of Scranton.

|

Scranton. Elevation 1,100 feet. Population 770. Kansas City 87 miles. Burlingame. Elevation 1,045 feet. Population 1,422. Kansas City 92 miles. |

The principal industry about Scranton is coal mining, but in the surrounding country there are also extensive agricultural interests. From Scranton southwest and west to Burlingame the route crosses a nearly smooth plain of shale which extends far to the east and for some distance to the west.

At Burlingame the railway crosses the line of the Santa Fe Trail from Kansas City to Santa Fe, N. Mex.1 This trail followed the top of the plateau from Olathe and went west from Burlingame 30 miles to Council Grove, which was an important depot. Quantrell planned to raid the town of Burlingame in 1863, while the men were absent in the Army, but the women built a fort of rocks and held their ground for six weeks until Union soldiers came to their assistance. This town was named for Anson Burlingame, formerly United States minister to China.

1This famous old highway was about 850 miles long. From 1804 to 1821 it had been traveled by a few trading expeditions using pack animals, but in 1821 it was formally opened for wagon travel, and caravans of "prairie schooners" and large wagons began to make their trips to the excellent market of Santa Fe, then an important Government and commercial distributing city of the northern part of old Mexico, and a point from which highways and trails extended down the valley of the Rio Grande and elsewhere. Later, after the United States had acquired the region, until the Santa Fe Railway was built, the trail was one of the great emigrant routes to the Southwest. At first the traders made only one trip a year, starting early in summer, as soon as the pasturage was promising, and arriving at Santa Fe in July. Early in the sixties the trade had increased to so great an extent that the caravans started every few days, and many were on the road during the season favorable for such travel.

The ordinary caravan consisted of 26 wagons, each drawn by five teams of mules or five yoke of oxen, but often there were 100 wagons in a caravan, divided into four divisions, a lieutenant having charge of each division under the command of an elected captain of the whole party. A day's journey was about 15 miles, but varied slightly with the distances to camping places. At night the wagons were formed into a hollow square inside which camp was made and the horses were corralled. Outposts were maintained for sentry duty, as the Indians often attacked such parties just at dawn.

East of Council Grove there was little to fear from the Indians, who were friendly to the white men. The Kansa tribe of Sioux had settled at the mouth of Kansas River but, persuaded by gifts, they abandoned one settlement after another as immigration progressed. So accommodating a spirit was not found among the tribes of the central Great Plains. The earlier trappers and frontiersmen had found most of these Indians amicable, but misdeeds by individuals of both races led to general bad feeling and convinced the Indians that they had nothing to gain from friendliness. Their hostility added greatly to the danger of travel on a trail that was already perilous enough through its lack of water and its physical obstacles.

In 1850 there were about 500 wagons and about 5,000 animals in the service, and in 1866 there were 3,000 wagons. On some trips as many as 180 yoke of oxen would haul two trains of wagons. In 1849 regular coach service carrying mail from Independence to Santa Fe was started, and in 1862 the service was daily. The trip required two weeks. The coaches carried 11 passengers, who were charged $250 each for the trip, including meals. The cost of the trip from Kansas City to Santa Fe now, including meals and sleeper, is less than $35 and the time required is 15 hours. Express charges for carrying money were $1 a pound for gold or silver.

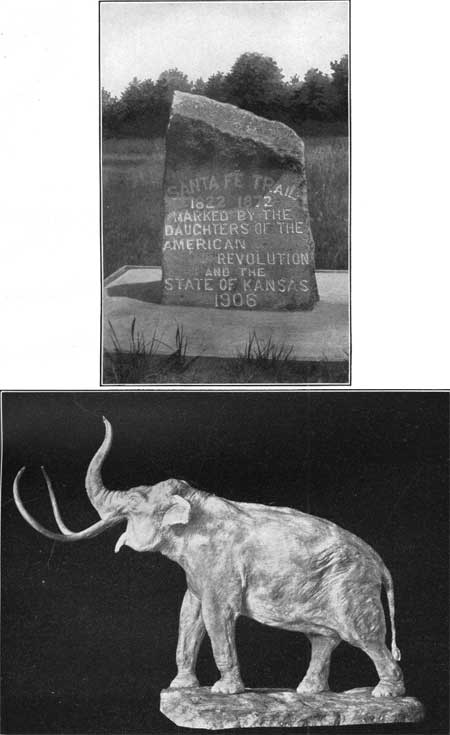

The Santa Fe Railway follows the old trail in general, but in places the two are not very close together. In eastern Kansas there were several lines of travel. One began at Independence, Mo., a short distance east of Kansas City, crossed the river to Westport, passed through the hills in Kansas City, and then went by Olathe and Gardner over the plateau southeastward to Council Grove, a famous rendezvous 25 miles northwest of the present city of Emporia. About halfway to Council Grove it was joined by a route from Fort Leavenworth, where most of the Government troops outfitted. The Santa Fe Railway now crosses this part of the trail near Olathe and again near Burlingame, about halfway between Topeka and Emporia. West of Council Grove the trail passed through the southern part of the city of Lyons, reaching Arkansas River near Ellinwood, a short distance east of Great Bend. From this place westward it followed the north bank of the river, in greater part within a very short distance of the course now taken by the railway, but in Colorado it kept on the north bank to Bents Fort, above Las Animas, where it crossed to the south side of the river. From this point into New Mexico the trail led southwestward, along a course very near the line of the present railway which crosses and recrosses it all the way to Raton. South of that place the trail went through Cimarron to Fort Union, near Watrous, thence to Las Vegas and across the Glorieta Pass to Canyoncito, whence it turned north to Santa Fe. A short-cut branch crossed the Arkansas above Dodge and went southwest to the Cimarron Valley and thence to Wagon Mound and Fort Union. Along much of its course the old trail is marked by granite monuments erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution. (See view of typical monument given in Pl. II, A.) The tracks of the trail are 200 feet wide in many places and consist of old ruts deeply scored into the sand. Sunflowers spread westward along the entire length of the trail and now mark its course at many places.

PLATE II.—A (top), GRANITE MARKER OF SANTA FE TRAIL. Blocks like this have been set at intervals along the old trail.

B (bottom), RESTORATION OF MAMMOTH. Elephas imperator, a large elephant that was common in the southwestern United States in Pleistocene time. From a model in the American Museum of Natural History, New York City.

Several coal mines are worked in the vicinity of Burlingame. A short distance west of the railway rises a prominent ledge of the Burlingame limestone, of which this is the type locality.

Beyond Burlingame the railway goes south and east of south across an undulating plain, making shallow cuts through the Scranton shale, which lies between the Howard limestone and the Burlingame limestone.

|

Osage. Elevation 1,077 feet. Population 2,432. Kansas City 101 miles. |

At Osage the Santa Fe crosses the Missouri Pacific Railway. The city is named from the Osage Indians a branch of the great Siouan family, some of whom formerly lived near the Kansa Indians, north of the Arkansas. In addition to its coal-mining industry, it is the center for the surrounding farming community. The plain rolling of shale continues from Osage southwestward to Reading. The highest altitudes attained on the divides are 1,165 feet, or slightly higher than in the region to the north.

|

Barclay. Elevation 1,171 feet. Population 681.* Kansas City 106 miles. Reading. Elevation 1,074 feet. Population 289. Kansas city 112 miles. |

Just south of Barclay the ledge of Burlingame limestone is prominent to the west, and several small outliers of it cap knolls that stand east of the railway.

West of Reading the railway turns to the west and within 2 miles rises over the ledge of Burlingame limestone, then goes across 75 feet of the overlying Willard shale to the Emporia limestone, which begins on a divide half a mile beyond milepost 100. This bed is crossed again in the next divide to the southwest, and also on the downgrade descending to Neosho River, which is reached near milepost 108. The Neosho is a stream of moderate size carrying the drainage of a wide area of east-central Kansas. In its north bank are bluffs of the Willard shale. South of the river is a long, wide flat extending 4 miles to and into Emporia. A mile east of the station at that place this line is joined by the Ottawa cut-off from Holliday.

|

Emporia. Elevation 1,134 feet. Population 9,058. Kansas City 127 miles by Topeka (112 miles by Ottawa). |

Emporia, the county seat of Lyon County, is an important business center for a wide area of farming country and is the site of the State Normal School, which has 2,600 students. Emporia is the type locality of the Emporia limestone, which here passes underground on its westward dip.

[The itinerary west of Emporia is continued on p. 22.]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006