|

California Division of Mines and Geology

Bulletin 182 Geologic Guide to the Merced Canyon and Yosemite Valley, California |

ROAD LOG 2

TRACY TO EL PORTAL VIA PATTERSON AND TURLOCK, CALIFORNIA*

By CLYDE WAHRHAFTIG

U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California, and

University of California, Berkeley, California

and L. D. CLARK

U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California

*Prepared cooperatively with the U.S. Geological Survey.

|

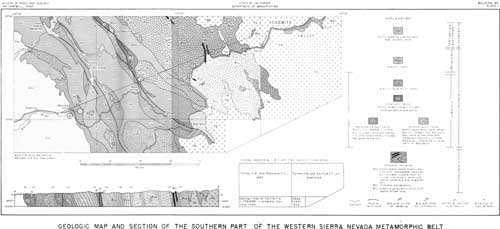

| Plate 1. Geologic map and section of the southern port of the western Sierra Nevada metamorphic belt, accompanies this paper. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Mileage | |||

| 0.0 | Junction of Highways U.S. 50-California 33. Turn right (south) on Highway 33. | ||

| 9.1 | Junction California 33 and 132. | ||

| 17.9 | Junction California 33 and road to Grayson and Modesto. | ||

| 24.5 | Turn left (east) onto Patterson-Turlock Road. | ||

| 27.4 | Cross San Joaquin River. | ||

| 40.2 | Center of Turlock (intersection Main and U.S. 99)—turn right (south) to first street past stoplight. | ||

| 40.3 | Turn left (east) off U.S. 99 on East Ave.—road to Snelling. | ||

| 40.2 to 46.0 | The road crosses the depositional surface on top of the Pleistocene Modesto formation of Davis and Hall (1959), equivalent to the upper part of the late Pleistocene Victor formation (Piper and others, 1939). The Victor formation is an alluvial fan. For a geologic description of the area between Turlock and Merced Falls, see the paper by R. J. Arkley in this guidebook. | ||

| 46.0 | The toad leaves the smooth depositional surface and enters slightly rolling topography carved in the Quaternary Riverbank formation of Davis and Hall (1959), equivalent to the lower part of the Victor formation. Outcrops of reddish sandy alluvium along the road at mile 47.8 are probably of this formation. | ||

| 48.2 | To the north can be seen a line of low, flat-topped hills carved in the Turlock Lake formation of Davis and Hall (1959). | ||

| 52.2 | The low, flat-topped hill about a quarter of a mile to the southwest (right) consists of Mehrten formation, of Miocene and Pliocene age, capped by a thin layer of Arroyo Seco gravel of middle or late Pleistocene age (R. J Arkley, this guidebook). | ||

| 52.5 | The road enters the area mapped as Turlock Lake formation by Davis and Hall, characterized by rolling country carved in reddish sandy alluvium. | ||

| 54.9 | North bank of Dry Creek. The roadcuts along the grade down to the creek expose two layers of thinly bedded fine sand and silt interbedded with coarse sand. These may represent glacial lake deposits (glacial rock flour) laid down by the Merced River. The terrace traversed by the road beyond Dry Creek is underlain by the Riverbank formation of Davis and Hall (1959). | ||

| 55.4 | The China Hat pediment (see article by R. J.

Arkley, this guidebook) can be seen across the Merced River, above

the trees at 2:00 o'clock. Just beyond this point the road descends 20 feet to the terrace surface of the Modesto formation. | ||

| 57.2 | On the skyline to the east across the river can be seen the westward-sloping China Hat pediment. | ||

| 57.9 | The road descends the terrace to the modern floodplain of the Merced River. The small outcrop at the base of the bluff is of thinly bedded fine sand and silt. This is overlain by 20 to 30 feet of well-sorted medium-grained sand of granitic detritus. | ||

| 61.6 | The abandoned grade visible at intervals on the right is that of the Yosemite Valley Railroad, which extended from Merced to El Portal and operated from 1907 to 1945. Its chief business was freight, but the railroad carried many Yosemite-bound travelers during the summer. | ||

| 65.5 | Snelling. Small white courthouse at Snelling,

erected in 1857, was the first in Merced County. Between Snelling and Merced Falls the road passes piles of dredge tailings. The gold mining dredges are large barges with chains of scoop buckets that gnaw away on one side of the artificial pond on which the dredge floats. The buckets feed into a large trommel on the dredge that separates the coarse gravel from the fine gold-bearing sand. This sand passes from the trommel over a complicated series of riffles which trap the gold. The barren gravel is carried up a long stacking arm by an endless belt and dumped on the side of the pond opposite from where it was dug. By excavating an one end and back-filling at the opposite end, the dredge carries along the pond on which in floats as it mines the gold. The dredge is anchored to the shore by cables and swings from side to side by pulling alternately on the cables, digging and stacking as it goes. This back and forth swinging from a fixed point gives the cursous cross ridges of the dredge tailings; from the air these tailings piles look like stacks of coins that have fallen over. The gravel that has been dredged here is apparently post-glacial alluvium deposited in the shallow steep-walled valley that the Merced River carved in the Pleistocene Modesto and Riverbank formations. The large size of the boulders in this gravel is very puzzling, for the Pleistocene alluvium contains no boulders of this size so far out from the mountains. In addition to gold, a small amount of platinum was recovered from the dredgings. With luck, one can see to the south the profile of the China Hat pediment. | ||

| 72.0 | Merced Falls. | ||

| 72.1 | Merced Falls dam and powerplant on right. The dam rests on the westernmost outcrop of bedrock, which consists of black slate with interbedded graywacke. | ||

| 72.3 | Sawmill ruins on right. | ||

| 72.5 | Cross abandoned grade of the Yosemite Valley Railroad. Exposures of steeply dipping Upper Jurassic slate. The metasedimentary rocks extending from here eastward to Stop 1 are on the western limb of a large anticline (pl. 1). Although the beds are in places complexly folded, tops are westward in intervening areas where bedding is not crumpled. | ||

| 72.7 | Continue straight ahead on Exchequer Dam road. | ||

| 72.8 | Cleavage and bedding in slate at left dip steeply. | ||

| 73.0 | Cleavage still dips deeply, but in minor folds bedding crosses the prominent cleavage. | ||

| 74.7 | STOP 1. Lunch. Stream-polished exposures on the

north bank of the Merced River show details of the structure of

much-deformed slate and graywackes. Some graded

graywacke beds can be found. The most prominent structures here are minor

folds that plunge southwest and southeast at angles of 70° and 80°.

These small folds are superimposed on beds that already dipped steeply

as a result of earlier folding about nearly horizontal axes. The

Jurassic slate of this area differs from most of that exposed farther

north in the abundance of minor folds and in the steep plunge of fold

axes. Return to Snelling-Hornitos Road. | ||

| 75.7 | Cross Merced River. | ||

| 76.7 | STOP 2. The flat-topped hill just west of the road is

capped by about 100 feet of coarse cross-bedded sandstone and

conglomerate of the Ione formation, which rests on deeply weathered

Jurassic slate. At the base of the hill can be seen outcrops of black

unweathered slate. Near the top of the hill, the sandstone can be seen

resting on bleached white slate. The sandstone contains pebbles of

bleached slate, volcanic rocks, and quartz. It is largely a quartz-kaolin

sandstone with a very low percentage of heavy minerals, all

extremely resistant to weathering, and was apparently derived from the

erosion of a terrain that had been deeply weathered in a tropical climate.

Casts of Venericardia planicosta have been reported from

the sandstone in this hill (Allen, 1929, p. 361). The flat-topped hills to the southeast, which slope gently southwestward, are also capped by about 100 feet of similar sandstone of the Ione, resting unconformably on the upturned edges of the Jurassic slate. If the hill crests are projected by eye eastward, they will be seen to coincide roughly in height with the even-topped ridges in the distance to the east, the foothill ridges of the Sierra. These ridges are underlain by metavolcanic rocks. | ||

| 76.9 to 79.9 | The road here passes through rolling country surmounted by the flat-topped mesas of the sandstone of the Ione. On the low, rolling hills can be seen the curious "hogwallow" microrelief of evenly spaced mounds 2 to 3 feet high, and about 20 to 40 feet across. See article by R. J. Arkley in this guidebook, for a discussion of the origin of this microrelief. | ||

| 79.9 | Whitish-weathered schistose felsite, probably Upper Jurassic. | ||

| 82.5 | Road crosses into Jurassic metavolcanic rocks. | ||

| 82.7 | Roadcuts in schistose metavolcanic rocks. | ||

| 83.3 | Hornitos (take left fork). | ||

| 83.4 | Adobe and stone buildings, some in ruins but others still occupied. Hornitos was settled in 1850 by Mexicans who were invited to leave the town of Quartzburg, about 4 miles to the northeast. Joaquin Murietta, a bandit idolized by some in Mother Lode history, is alleged to have once escaped through a tunnel leading from a building here. One of the ruined buildings once housed the store of D. Ghirardelli, who later went into the chocolate business. From the Wells Fargo office, established in 1852, gold shipments of $40,000 per day are reported, and the population of Hornitos reached a high point of about 15,000. The name Hornitos means "little ovens" and was derived from the dome-like bake ovens constructed here by a group of Germans. | ||

| 84.6 | Schistose amphibolite in roadcuts. | ||

| 85.4 | Old placer diggings in Burns Creek on the right. | ||

| 87.1 | Quartzburg school. Site of the gold-rush town of Quartzburg. | ||

| 88.7 | Take left fork of road. | ||

| 90.7 | Hunter Valley Road on left. Continue straight ahead toward Bear Valley. | ||

| 91.1 | Hunter Valley extends to the northwest (left). Bedded Upper Jurassic tuff dips about 60° northeastward in road cuts on the right. | ||

| 92.7 | View ahead of Bear Valley and Bullion Mountain. The floor of Bear Valley, at an elevation of about 2,000 feet, is probably a surface of the Broad Valley stage of the Merced River. Bullion Mountain, which has a present elevation of 4,200 feet, therefore probably stood at least 2,200 feet above the Broad Valley stage of the Merced River (approximately equivalent in age to the Ione formation or the auriferous gravels). Bullion Mountain is held up by resistant metavolcanic rocks while Bear Valley is carved in soft slate of the Mariposa formation. The Mariposa formation is separated from the metavolcanic rocks by the Melones fault zone which is concealed by mass wastage debris on the lower slopes of the mountain. | ||

| 93.8 | West contact of the Mariposa formation. | ||

| 94.4 | Junction State Highway 49 at Bear Valley. Turn

left (north) on Highway 49. The town was the site of

Col. John C. Fremont's headquarters after he had purchased

the Mariposa land grant in 1847. Fremont operated lode

gold mines and a stamp mill until 1863. The road north is over the rolling upland surface of Bear Valley at altitudes of 2,000 to 2,300 feet. From Bear Valley to the Pine Tree mine (Stop 3), and back to Mariposa, the route follows the Mother Lode, a geographic belt 2 to 3 miles wide in which a system of discontinuous eastward-dipping quartz veins crops out. Lode gold deposits are not restricted to the Mother Lode belt, but within it the quartz veins and ore bodies are more numerous and can be followed farther in mining than elsewhere in the Sierra Nevada. The gold is associated with the quartz veins, but in many mines gold in the quartz is relatively scarce; the ore was formed by replacement of the rock adjacent to the veins. Many Mother Lode veins and ore bodies are within the Melones fault zone, but they are related to smaller faults that are apparently younger than the chief movements of the fault zone. | ||

| 95.8 | Edge of the canyon of the Merced River. The topography drops abruptly away to Hell Hollow, the ravine directly below, and the Merced River, 1,400 feet below and 2 miles north of this point. | ||

| 96.9 | Contact between Mariposa formation and serpentine. The Mariposa formation is sheared for a distance of about 100 feet westward from the serpentine as a result of movement on the Melones fault zone. The fault zone here includes the serpentine and the sheared part of the Mariposa formation. | ||

| 97.2 | STOP 3. Pine Tree mine. Walk out to point north

of iron tanks while bus is turning around. North and east from this

point can be seen the Merced Canyon and also the Broad Valley surface,

which is marked by accordant ridge crests at or just above our level on

the north side of the river. These accordant crests rise north of us to

the base of a mountain (Buckhorn Peak), which is crowned by a flat area

more than a mile across (Buckhorn Flat, altitude about 3,400 to 3,500

feet) that is nearly 1,200 feet above the Broad Valley stage of the

Merced River. Buckhorn Flat is cut across steeply dipping metavolcanic

rocks. Northeast of Buckhorn Flat, and several hundred feet below it, is

an extensive gently rolling upland cut across the steeply dipping

Paleozoic Calaveras formation. Patches of auriferous gravels have been

found on this upland (Turner and Ransome, 1897). Due east can be seen the High Sierra, with a few of the higher peaks (possibly Mr. Clark and Red Peak, 11,500-11,600 ft.) rising from behind the even-topped forest-covered ridges of the Sierra upland that form the skyline. At the head of the Merced Canyon, the tops of El Capitan, Half Dome, and Clouds Rest, three of the famous monuments of Yosemite Valley, can be seen rising slightly above the forested plateaus. If, in mind's eye, the canyons be filled in up to the level of the Broad Valley stage, a rough picture of the appearance of the Sierra Nevada in Eocene time can be obtained. The Pine Tree gold mine, at the head of the ravine to the south, recovered ore from the Pine Tree vein, discovered in 1849, and from the Josephine vein, discovered shortly thereafter. The mine operated intermittently from 1849 to 1944, part of the time under the ownership of Col. Fremont, and has a recorded production of about $3,400,000 from 8 miles of workings. The total production is probably greater than $4,000,000. Mariposite, a bright-green chrome mica, is among the minerals found here. (Notes on mine statistics and history in this road log are from Bowen and Gray, 1957.) Return to Bear Valley on California 49. | ||

| 100.0 | Town of Bear Valley. Ruins of adobe and stone buildings on left. | ||

| 105.1 | Site of Mr. Ophir Mint. This was an officially sanctioned private mint established in 1851; for a short time it manufactured hexagonal $50 gold slugs to ease a currency shortage. The white quartz vein and diggings at the top of the hill ahead mark the site of the Mr. Ophir mine. Discovered in 1849 or 1850, the mine was operated intermittently until 1914. Recorded production is $85,703, but total production is estimated at about $270,000. | ||

| 106.7 | Town of Mt. Bullion. The Princeton group of mines is on the Mt. Bullion-Cathay road at the southern outskirts of Mt. Bullion. The Princeton mine, discovered in 1852, produced about $5,000,000 in gold from workings that extended to a depth of 1,250 feet. Most of the ore carried between $4 and $7 per ton in gold, but near-surface ore yielded about $70 per ton. No sustained mining has been carried on since 1927. | ||

| 108.2 | Contact between serpentine in the Melones fault zone and greatly sheared slate and conglomerate of the Mariposa formation. The long axes of the elongate conglomerate pebbles are nearly-vertical. | ||

| 108.8 | Road follows contact between serpentine on the right and metavolcanic rocks on the left for the next half mile. | ||

| 111.5 | Junction California 49 and California 140. Turn right (southeast) into Mariposa. "Mariposa" means butterfly. | ||

| 112.2 | Rest stop. Turn around. Leave Mariposa traveling toward Yosemite Valley on California Highway 140. | ||

| 112.9 | Junction California 140 and 49. Continue ahead on 140. From here to mile 117.2 steeply dipping metavolcanic rocks with some interbedded slate are exposed in the roadcuts. | ||

| 114.4 | Small body of talc-antigorite schist enclosed in metavolcanic rocks. | ||

| 116.5 | Mariposa summit. 116.5 to 121.0: the highway passes down the valley of Bear Creek, a broad gentle valley probably graded approximately to the Merced River of the Broad Valley stage (Hudson, 1960, fig. 2. p. 1551). | ||

| 117.2 | Highway enters an area underlain by a granitic rock. | ||

| 117.8 | Highway passes from the granitic area back to metavolcanic rocks. | ||

| 121.0 | The grade of Bear Creek steepens somewhat, the canyon narrows, and the stream has carved incised meanders. The segment of the stream from 121.0 to 123.1 was probably graded to the Merced River of the Mountain Valley stage. | ||

| 122.8 | Bridge over Bear Creek. | ||

| |||

| 123.1 | STOP 4. Bear Creek here plunges over a fall held up by the resistant metavolcanic rock and descends the abrupt canyon ahead to the Merced River. This is probably the nickpoint between the segments of Bear Creek graded to the Mountain Valley stage (above) and to the present stream in its canyon (below). | ||

| 123.7 | Contact between steeply dipping metavolcanic and meta sedimentary rocks, both parts of the Calaveras formation of Paleozoic age. | ||

| 123.7 to 125.4 | Steeply dipping planar structure in Paleozoic slate exposed on the left is cleavage. Bedding is in general nearly parallel to the cleavage, but often crosses it. | ||

| 125.4 | Briceburg. | ||

| |||

| 125.5 | STOP 5. Slate and thin-bedded chert (Calaveras formation)

are here greatly sheared and the only structures remaining are

the steeply plunging lineations and minor folds related to the last

stage of deformation. From here to mile 130.5, the Calaveras formation

consists of phyllite derived from siltstone that locally contained

interbedded chert. Bedding is preserved in part of this interval, but in

other parts has been destroyed by shearing as it is here. Granitic boulders are abundant in glacial outwash resting on water-polished bedrock in cuts on the south side of the road at Stop 5. Since the gravel consists largely of well-rounded boulders of granite and granodiorite, it must have been transported by the river, for the bedrock for many miles upstream from this point consists of metasedimentary rocks. Over the outwash gravel is colluvium derived from the slope above. | ||

| 126.6 | Boudinages in steeply-dipping mafic dike in large cut on the right. | ||

| 127.8 | STOP 7 (return trip). Outwash gravel exposed in the roadcut may indicate two layers of outwash, separated by a period of dissection when ice retreated in the headwaters of the river. In the lower 10 feet of the gravel many of the boulders of granodiorite and granite are rotted to granite sand; maximum size of the boulders is about 4 feet, but this is no larger than boulders now being moved by the Merced River on the other side of the road. The upper 20 feet of the exposure, separated from the lower part by a row of boulders slumped from the hillside above, consists of finer gravel (about 1 foot average size) composed of largely unweathered boulders of granite and granodiorite. The upper gravel may be of Tioga or Graveyard (of Birman, 1957) age, probably the latter, and the lower gravel Tahoe or Sherwin in age (see table 1, Wahrhaftig). | ||

| 129.6 | Crossing Feliciana Creek, one of Matthes' classic areas of the Broad Valley stage. | ||

| 129.7 | Quartz ladder veins in dikes to the right. | ||

| 130.5 | Thin-bedded metachert of the Calaveras formation, locally contorted. The light-gray-weathering more massive rock is limestone, traceable from here to about 1 mile north of the quarry at mile 132.0. | ||

| 131.6 | Small granitic stock to the north across the river. | ||

| 131.8 | Inactive limestone quarry. Limestone from this quarry was used in Merced for the manufacture of Portland cement. The geologic structure on hillsides to the north (left) is brought out by the resistant metachert and limestone beds. | ||

| 133.6 | STOP 6. Geologic marker. Tightly and complexly folded metachert and black phyllite of the Calaveras formation. The folds all plunge steeply, but the bearing of the fold axes and attitudes of axial planes are not consistent. | ||

| |||

| 134.2 | Landslide debris in roadcut on the right. The scarp at the top of the slide, not visible from this point, is near the crest of the ridge. Looking downstream from this point the V-shaped canyon of the Merced River is well displayed. | ||

| 134.5 | Young glacial outwash gravel or hydraulic mine tailings on right. | ||

| 135.0 | Bridge across the South Fork of the Merced River. | ||

| 136.5 | Waste dumps of the Clearing House mine can be seen to the east across the river. The ore was discovered in 1860, and before mining ceased in 1937, the mine had yielded more than $3,350,000 in gold, some silver, and small amounts of copper and lead. Granodiorite exposed on hill north of the mine. | ||

| 136.9 | Southwestern contact of an isolated granitic pluton. | ||

| 137.1 | Gold Star mine on right. The mine produced small amounts of gold from 1936 to 1952. | ||

| 137.3 | On the spur on the canyon wall to the north (left) can be seen the trace of the incline where log-laden flatcars were lowered from spur lines on the gently rolling upland surface above to the main line of the Yosemite Valley Railroad near river level. | ||

| 137.4 | Dumps at the Rutherford gold mine are visible north of the river. The production is not recorded but there are several reports of high-grade ore. | ||

| 137.8 | Outwash gravel in roadcut. | ||

| 138.2 | Northeastern contact of granitic pluton. | ||

| 138.3 | Spheroidally weathered boulders of granitic rock. | ||

| 139.7 | Southwestern contact of a granitic body. The highway crosses metamorphic rock from 139.7 to 140.2. | ||

| 140.2 | Northeastern contact of a granitic body. | ||

| 140.4 | The flat area to the left marks an abandoned meander of the river. | ||

| 140.6 | The sheet-iron structure at the base of the hill on the far side of the river is a mill that processed tungsten ore from mines in this vicinity. | ||

| 141.1 | At this point, the canyon of the Merced River widens out and is U-shaped. Downstream from this point the canyon is V-shaped and winding, and there is some question as to how far below this point ice actually extended. There is no question that ice reached this far downstream on the Merced River in the oldest glacial stages recognized on the west side of the Sierra. | ||

| 141.2 | Tunnels in the sharp ridge north of the river are workings of the El Portal barite mine. Most of the nearly 400,000 tons of barite produced was used in oil-well drilling mud. The mine has been idle since 1948. | ||

| 142.0 | Bridge across Merced River. | ||

| 142.3 | Metamorphic rocks across river to the right. | ||

| 142.6 | El Portal. (Gasoline station at east end of town.) | ||

| 142.7 | Contact between Calaveras formation and part of the Sierra Nevada batholith. | ||

References

Allen, Victor T., 1929, The Ione formation of California: Univ. California, Dept. Geol. Sci. Bull., v. 18, p. 347-448.

Birman, Joseph H., 1957, Glacial geology of the upper San Joaquin drainage, Sierra Nevada, California: Univ. California at Los Angeles, Ph. D. thesis, 237 p.

Bowen, O. E., Jr., and Gray, C. H., Jr., 1957, Mines and mineral deposits of Mariposa County, California: California Jour. Mines and Geology, v. 53, p. 35-243.

Davis, S. N., and Hall, F. R., 1959, Water quality of eastern Stanislaus and northern Merced Counties, California: Stanford Univ. Pub., Geol. Sci., v. 6, no. 1, 112 p.

Hudson, F. S., 1960, Post-Pliocene uplift of the Sierra Nevada California: Geol. Soc. America Bull., v. 71, p. 1547-1573.

Piper, A. M., Gale, H. S., Thomas, H. E., and Robinson, T. W., 1939, Geology and ground-water hydrology of the Mokelumne area, California: U.S. Geol. Survey Water-Supply Paper 780, 230 p.

Turner, H. W., and Ransome, F. L., 1897, Geology of the Sonora quadrangle: U.S. Geol. Survey Folio No. 41.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

state/ca/cdmg-bul-182/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 03-Aug-2009