|

Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1766

The Water Supply of El Morro National Monument |

THE POOL BY INSCRIPTION ROCK

In the land of enchantment, between Gallup and Grants, N. Mex., near the Zuni Mountains, a huge sandstone bluff rises abruptly 200 feet above the plain. The Spaniards called it "El Morro," which means "the headland" or "bluff." Around it are other mesas and canyons and stands of piñon and ponderosa pine. Other great rocks are nearby, but none are as popular as El Morro, and none have been as important to the traveler.

For at El Morro there is water.

In that country, water is scarce and precious. In the old days, travelers from Santa Fe would tell each other about the pool of clear, refreshing water at the base of the huge rock. This is the story of the great bluff, its water supply, and the rocks around it.

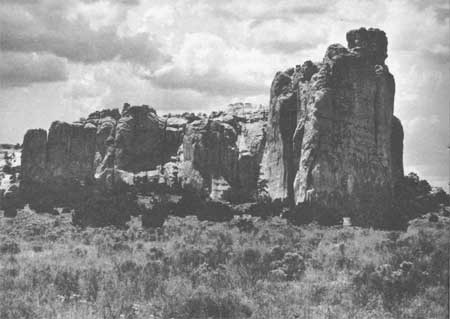

In the late summer of 1849, an American lieutenant of the Topographical Engineers, James H. Simpson, accompanied infantry and artillery troops on a reconnaissance march from Santa Fe into the Navajo Country. On September 18, at the urging of one Mr. Lewis, an Indian trader, Lieutenant Simpson left the main party in order to see "half an acre of inscriptions" [1] upon a huge rock (fig. 1) . Although somewhat dubious, the Lieutenant had allowed himself to be persuaded by Lewis that the trip was worthwhile. Taking with him an artist named R. H. Kern, another man by the name of Bird, and Mr. Lewis as guide, he set off through miles of desert country, filled with huge red and white sandstone rocks, "some of them looking like steamboats, and others presenting very much the appearance of façades of heavy Egyptian architecture." [2]

|

| Figure 1. Inscription Rock, El Morro National Monument, New Mexico. |

As they drew near the huge mass of rock, they dismounted and went up close. There were the inscriptions. "Perhaps not half an acre," wrote Lieutenant Simpson, cautiously. But there were enough to be an exciting find: "One of them dating as far back as 1606, all of them very ancient, and several of them very deeply as well as beautifully engraven." [3] Simpson tried to remain objective, but excitement and interest kept breaking through. He knew he had found something of enormous interest to historians and to Americans generally.

He and his friends decided to stay overnight, in order to copy the inscriptions. Simpson knew that without facsimiles their report might not be believed—just as he himself had been doubtful of Lewis' story.

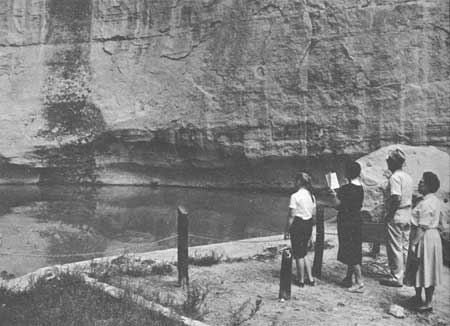

Looking for water and a place to camp, they rounded a corner of the rock and came upon the pool, "canopied by some magnificent rocks, and shaded by a few pine trees, the whole forming an exquisite picture." [4] Kern has left us a charming sketch of it. This lonely little scene had the wild and primitive beauty which Europeans looked for in the novels of Fenimore Cooper, and which Americans were learning to love and recognize as their own.

Lieutenant Simpson thought the water came from springs, but actually the pool is fed by rains and melted snow. After improvements, it is 12 feet deep when it is full, and holds about 200,000 gallons of water (fig. 2).

|

| Figure 2. The pool at El Morro as it is today. (National Park Service photograph, by Jack E. Boucher) |

Lieutenant Simpson was the first American official to visit El Morro. Although it is a military report, his account is delightful to read, full of personal touches and expressions of a sense of beauty and wonder not characteristic of official reports. With Bird and Kern, he copied all the inscriptions they could find, carefully noting that there was not a single inscription in English upon the rock. Then they too left their names inscribed on the rock (fig. 3), and set off to rejoin the troops and tell the story of their discovery.

|

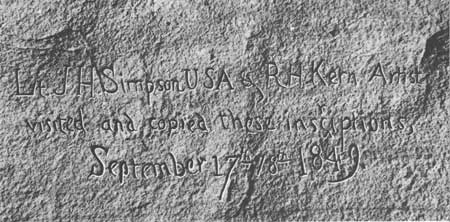

| Figure 3. Facsimile of Simpson-Kern inscription. |

From that day to this, Americans have been visiting El Morro. A few years after Simpson's visit to El Morro, a Captain Sitgreaves passed by the rock on an expedition down the Zuni River. It is briefly mentioned by his surgeon, Dr. Woodhouse, in a description of the natural history of the region. [5]

In 1858 Edward F. Beale, in the course of a survey of the wagon road from Fort Defiance to the Colorado River, stopped briefly at the rock:

When at 9 a.m., we reached Inscription Rock, I was tired of exclaiming, as every hundred yards opened up some new valley, "how beautiful." The rock itself seems to be a centre from which radiates valleys in all directions, and of marvelous beauty. It rises grandly from the valley, and the tall pines growing at its base give out long before they reach the top of its precipitous face. Inscriptions, names and hieroglyphics cover the base, and among the names are those of the adventurous and brave Spaniards who first penetrated and explored this country * * * the rock is some three or four hundred feet in height, and the spring almost hidden in the cavity of it * * * [6]

Beale's trip was especially interesting, because he commanded a caravan of camels that were imported as an experiment in transportation for the arid Southwest. However, the railway train soon made its appearance and put an end to camel trains.

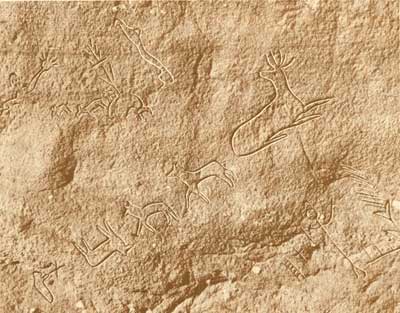

Long before the Spaniards arrived, the Zuni Indians had constructed a village on top of the headland, and carved a path on the face of the cliff between the village and the waterhole. Ruins of this village, fragments of pottery, and interesting carvings on the face of the cliff gave one a glimpse into the lives of these prehistoric inhabitants (fig. 4).

|

| Figure 4. Prehistoric Indian village on top of Inscription Rock. |

For nearly 200 years, El Morro was the principal watering-point for Spanish travelers between the villages of Acoma and Zuni. Here they found shelter from the sun and from storms, and at the pool, fresh water for their horses, and for their own needs.

The first written record of El Morro dates from 1583. A Spanish visitor, Diego Perez de Luxan, mentions in his journal, "El estanque del penol,"—"The Pool by the Great Rock." [7]

The earliest inscription by the Spaniards was that of Don Juan de Oñate in April, 1605, who wrote, "Pasó por aquí el Adelantado Don Juan de Oñate del descubrimiento de la mar del sur a 16 de Abril de 1605." [8] (Passed by here the Governor Don Juan de Oñate, from the discovery of the Sea of the South, on April 16, 1605). It is impressive to think that Oñate's name was inscribed on the rock 15 years before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth! We do not know whether other explorers preceded him and left no record inscribed on the rock. Many other Spanish travelers who visited the waterhole between Oñate's visit in 1605 and the last recorded Spanish visit in 1774, left inscriptions on the sandstone cliff.

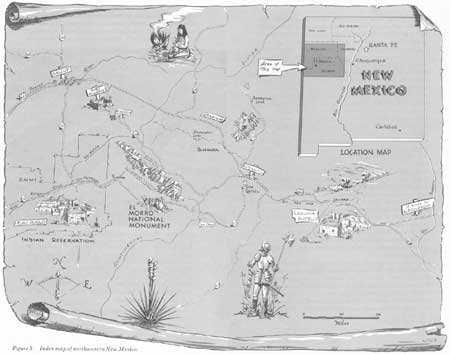

Because fresh water was so important to all travelers in this area, the trail past El Morro became the principal road across the region. Names of wagon-train emigrants, traders, Indian agents, soldiers, surveyors and settlers, were inscribed on the rock in the years following 1850 (fig. 5).

|

| Figure 5. Index map of northwestern New Mexico. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

After the transcontinental railroad and U.S. Highway 66 were constructed 25 miles to the north, the road by the watering place lost its prominence and became little used for a time. Improvement of the road past El Morro (State Highway 53) was begun in 1955, and by 1962 construction was almost complete.

El Morro National Monument was established by Presidential proclamation in 1906 to preserve the rock carvings and the pool of water that had contributed so much to the exploration and development of the Southwest. There were always some visitors to the monument, but after the improvement of the road, they began to come in greater numbers. In 1961, nearly 20,000 tourists visited El Morro. Ironically, the pool of fresh water that gave prominence to El Morro for 300 years is now inadequate to supply the large numbers of visitors, tourists, and the monument staff. Eventually, most of the water supply had to be hauled by truck from San Rafael, 38 miles northeast of the monument, and later from a well 3 miles to the south. Although its charm remains, Lieutenant Simpson's "exquisite" pool has outlived its usefulness as a water supply.

The waterhole, gouged by rain and snowmelt that cascaded off Inscription Rock through the centuries, is protected from the bright sunlight of this semiarid region. Precipitation in the area averages about 12 inches a year, according to records of the U.S. Weather Bureau. Streams do not exist in the area, except for a short spring-fed stream in Water Canyon, 6 to 7 miles north east of the monument. Wells are scattered widely, and failures have been common.

It is often thought that this region was at one time green and verdant and that the present desertlike appearance is the result of overgrazing. However, the accounts of the expeditions of Simpson and Beale and those by other trustworthy travelers reveal that, although grass did grow well in certain areas, "there were also many areas * * * where grass was so poor that forage for a string of horses could hardly be obtained." [9] Rainfall tends to run off the land or evaporate very quickly where there is not sufficient plant life to catch and hold it. Some of it, of course, does sink into the soil and eventually seep into the rocks under the soil cover. There, under the earth's surface, is the source of more water for the monument—what we call ground water.

3Simpson, 1852, p. 99. Some inscriptions date further back than 1606.

7El Morro National Monument: U.S. Dept. Interior Pamphlet.

8El Morro Trails: Southwestern Monuments Association, Globe, Ariz., p. 4—5.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

wsp/1766/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 01-Mar-2005