|

GLACIER BAY

Land Reborn: A History of Administration and Visitor Use in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve |

|

| PART ONE: SCIENCE AND MONUMENTALISM, 1879-1938 |

Chapter III:

Preserving A Laboratory And A Landscape

In December 1922, Dr. William S. Cooper, assistant professor of botany at the University of Minnesota, presented the early fruit of his long-term Glacier Bay study to his colleagues at the annual meeting of the Ecological Society of America in Boston. In the discussion following his talk, the idea developed that Glacier Bay ought to be preserved as a reservation of some sort and that a committee ought to be formed to consider a course of action. Cooper would later insist with characteristic modesty that the proposal to form that committee came from Barrington Moore, a consulting forester and former president of the Ecological Society, and that "Barrington Moore is thus to be credited with initiation of the project which attained success three years later." [1] But more importantly, the Ecological Society appointed Cooper to chair the committee, and asked him to report the committee's recommendation at the Society's next annual meeting. With this appointment, Cooper commenced his role as founder and patron of Glacier Bay National Monument.

Cooper admirably personified what historian Stephen Fox has described as the "radical amateur" in the American conservation movement. Radical amateurs dedicated time, money, and emotional fervor to their cause as an adjunct to their professional careers. They held themselves aloof from government agencies or salaried positions in conservation organizations. Fox calls them radical because they exuded independence and integrity. "Unhampered by bureaucratic inertia or a political need to balance constituencies and defend old policies, they served as the movement's conscience." Working in tandem with professional conservationists, the radical amateurs provided "flexibility, vision, innovation, honesty, and zeal...in the tradition of John Muir." It is Fox's contention that radical amateurs were "the driving force in conservation history." [2]

This overstates the case. Cooper's vision of a nature preserve at Glacier Bay, like most conservation measures originating with the radical amateur tradition, would be blunted by opposition groups and only partially fulfilled. Conservation measures usually involved multiple federal agencies, whose professional staff provided the time and expertise to shape and implement the radical amateurs' proposals. Often, as was the case with the establishment of Glacier Bay National Monument, a conservation measure entailed negotiation and compromise between sister agencies in the Department of the Interior, whose officials were used to serving particular constituencies and economic interests. In this process the radical amateurs were peripheral, the professional bureaucrats central to decision-making.

The Park Service was less than a decade old and still a small agency when the Ecological Society of America made its proposal. The NPS did not have the field staff in southeast Alaska nor the control of local information that either the General Land Office or the U.S. Geological Survey possessed. For information it relied on other agencies and the radical amateurs. The small size of the Park Service put its officials at a distinct disadvantage in negotiations with other federal officials over the boundaries of the new national monument and the disposition of the mineral resources therein.

The Campaign for a National Monument

The Ecological Society's committee on Glacier Bay comprised Cooper, Moore, Robert F. Griggs, and Charles C. Adams. It was Griggs's idea to campaign for the establishment of a national monument rather than a national park, as the former could be created by presidential proclamation while the latter required an act of Congress. "In the first case," Griggs wrote, "it is necessary only to convince one man of the advisability of the action, while in the second six hundred, more or less, must be converted to the idea." Griggs noted that Congress could later redesignate the area a national park. [3]

This was a tactical choice. The committee did not enter into the contemporary debate over what really distinguished the two. Superintendent of National Parks Robert B. Marshall had said in 1917 that the main difference between a national monument and a national park was that the former was merely protected from encroachment by private interests, while the latter was in process of development by roads, trails, and hotels for the vacationing public. Others, including Horace Albright, the second director of the Park Service, thought that national monuments and national parks were "practically identical." [4] Still another view emphasized the reference in the Antiquities Act to the president's prerogative to establish national monuments for the protection of historic and prehistoric features and "other objects of scientific interest." Although Glacier Bay's scientific interest would figure prominently in the Ecological Society's proposal, the committee did not fix on national monument designation for this reason. The committee members seemed to have in mind that there was no significant difference between a national park and a national monument other than status, and Congress could later upgrade a national monument to national-park status.

Another tactical decision, and one which demonstrated that the committee was more pragmatic than radical, was the solicitation given to mining interests in the area. Cooper asked for opinions from geologists Harry Fielding Reid, Lawrence Martin, J.B. Mertie, Jr., all of whom had personal knowledge of Glacier Bay, and Alfred H. Brooks, who had traveled widely in Alaska and was chief Alaskan geologist of the U.S. Geological Survey. Of the four, Brooks was probably most concerned about Glacier Bay's mineral potential, but he did not yet raise any strong objections. Cooper characterized their responses as "all more or less favorable." When Cooper recommended approximate boundaries for the monument, he offered two alternatives: a minimum area encompassing the entire Glacier Bay drainage including the Gustavus forelands, or if politically feasible, everything from the outer coast to Lynn Canal. He noted that the Treadwell Mining Company was prospecting around Lituya Bay on the outer coast, "which might produce difficulties." [5]

The Ecological Society adopted this same moderate approach after hearing the committee's report at the next annual meeting in Cincinnati. The society passed a resolution urging the establishment of a national monument "for permanent scientific research and education, and for the use and enjoyment of the people." The society based its argument on five principal criteria: the unique and awe-inspiring spectacle of tidewater glaciers, the accessibility of those glaciers to ordinary travel, the scientific interest associated with glacier recession and ecological change, the magnificence of the coastal forest and its relationship to ecological studies in the Glacier Bay drainage, and the uselessness of the area for Alaska's economic development. The last point was key: preservation would not impair economic growth. The society sent copies to President Calvin Coolidge, the secretary of the interior, the director of the National Park Service, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and the governor of Alaska. [6]

Perhaps the Ecological Society's pragmatic, businesslike approach was realistic, given the importance of mining in Alaska's economy. (Congress, which created Mount McKinley National Park in 1917, allowed prospecting and mining within its boundaries.) The society's negative argument that the land was useless for any other purpose merely echoed the rhetoric of congressional debate on most national park bills. This was a political pattern that historian Alfred Runte has dubbed the "worthless lands" justification for creating national parks. [7] Nevertheless, the weakness of this approach for Glacier Bay National Monument soon became manifest, for it invited opponents of the monument to make geologic surveys of the highly mineralized shoreline areas of the bay which were likely to contain valuable ore. Mining companies were reluctant to undertake such an effort for themselves, but they had a powerful ally in the federal government, the U.S. Geological Survey. There was some irony in this, since both the Geological Survey and the Park Service were under the Department of the Interior. But it was hardly the first time that the Park Service found itself at cross purposes with a sister agency.

Mineral development was central to the federal government's plan for making the territory of Alaska worth the cost of administration. Following the chaotic years of the Klondike gold rush, mineral development proceeded more cautiously, with considerable help from the federal government. Alfred H. Brooks of the U.S. Geological Survey had been supervising a staff of field geologists and topographers in Alaska since 1898. In 1923 he had ten parties engaged in mineral investigations and surveys throughout the territory. "The need of geologic surveying as a basis for industrial development," he wrote in that year, "is so generally recognized that it requires no argument. It is especially important in new lands, however, to furnish the scientific facts on which to assure an orderly industrial development, and to avoid the hit or miss policy which has been so often disastrously employed." [8]

Hard-rock mining of gold ore accounted for most of Alaska's mineral production through 1924. By far the largest producer in the territory was the Alaska Juneau Gold Mining Company, whose workings honeycombed Mount Juneau within walking distance of the territorial capital. Other companies operated mines on Chichagof and Admiralty islands, and in the mining districts around Sitka and Ketchikan. In the immediate vicinity of Glacier Bay prospectors had already staked claims on Lemesurier Island in Icy Strait, and Francis Island in the bay itself. Placer mining in the early 1920s still accounted for a considerable part of Alaska's mineral production, too. A small community of placer miners worked the beach sands on the coast north and south of Lituya Bay from 1915 to 1917. Each heavy storm brought a fresh inundation of gold-bearing sand, which had to be recovered quickly before the tides sucked it out to sea. [9]

When Alfred Brooks heard from Cooper about the Ecological Society's resolution, he wrote back: "I do not think it is possible or advisable to establish a park in Alaska from which the prospectors are shut out." [10] Brooks sent his man in southeast Alaska, A.F. Buddington, to examine Glacier Bay. Buddington talked to prospectors on Lemesurier and Francis islands, and, on the basis of their information and a few assays of some quartz veins, he reported molybdenum, silver, and gold in the area. [11]

While the U.S. Geological Society positioned itself to lead opposition to the national monument, the Ecological Society enlisted strong support from conservation organizations. The society had a ready vehicle for this effort in its Committee on Preservation of Natural Conditions, which maintained a list of scores of conservation groups spread throughout the nation. The society obtained a most important endorsement for its proposal from the Council on National Parks, Forests, and Wild Life at the council's meeting in New York on March 4, 1924. The council comprised representatives from twenty-eight large organizations and often came to the defense of national parks by organizing letter-writing campaigns and by lobbying congressmen. Eventually the Ecological Society received letters from more than eighty groups reporting that they had conveyed their support for a national monument to the Department of the Interior. [12]

With rumblings of dissent coming from the U.S. Geological Survey, however, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work informed Cooper that he would not recommend proclamation of a national monument to President Coolidge until the area had been surveyed by an official of the Interior Department. Such a study would assess the necessity for a national monument and recommend boundaries. (Secretary Work did not inform Cooper that the study would be performed by a man with an eye for mining prospects, though Cooper probably guessed as much.) In the meantime, Work asked the President to sign an executive order making a temporary withdrawal of the area from land entry pending the Department's study. The withdrawn area essentially conformed to the larger boundaries proposed by Cooper. It extended from the outer coast all the way to the west shore of Lynn Canal. [13]

The withdrawal, announced on April 1, 1924, brought loud protests from the citizens of southeast Alaska. Chambers of commerce in Juneau, Haines, and other communities sent letters to the Coolidge administration denouncing the proposed national monument and pointing out the agricultural and mineral potential of the lands. Homesteaders in the Gustavus forelands area wrote: "Your petitioners have located their homesteads and toiled for years in anticipation that settlers would gradually enter and develop this great scope of rich farming country." The withdrawal, they declared, "would blight all such hopes." [14] The editor of the Alaska Daily Empire branded the withdrawal "a monstrous crime against development and advancement." The editor ridiculed the concept of protecting glaciers that "none could disturb if he wanted," and holding good timber and agricultural lands for "the study of plant and insect life." He ended by railing against the "conservation faddists" who were behind the government action. [15]

Cooper wrote a long reply to this editorial. His letter is significant not for its intended effect on Alaskan opinion so much as for its expression of Cooper's vision for Glacier Bay National Monument. Cooper emphasized two points from the Ecological Society's resolution--glaciers and the mature forest. Of the latter, he wrote:

The time is not far distant when, due to destruction, and proper use as well, our forests will have lost their primeval significance. We have no desire to lock up permanently the forest resources of the country, but only to reserve a few small areas so that our children may enjoy the beauties of nature untouched by men. It may be argued that the forest reserves accomplish this end, but the purpose of the forester is to conserve the timber supply, allowing cutting under proper safeguards, and this will inevitably involve serious disturbances of natural conditions.

Cooper then linked the importance of glaciers and forest together:

The Glacier Bay region is uniquely fitted for the purpose of such a reservation because it presents great variety in its forest covering; mature areas, bodies of youthful trees that have become established since the retreat of the ice, and great stretches, now bare, that will become forested in the course of the next century. Such an undisturbed forest makes an essential part of the setting of the chief features, the glaciers. The glaciers themselves can hardly be harmed, but the forests can very easily be ruined.

Cooper also argued for the national monument on the basis of economics, suggesting that future tourism in Glacier Bay would bring money into Juneau's economy. "Hotels on the shores of lower Glacier Bay, motor boats carrying visitors to its many points of interest. Why not? Is this fantastic?" [16]

About this time Cooper began to entertain doubts about the size of the temporary withdrawal. In his letter to Alaskans he maintained that the area had been "purposely and rightly, made large, in order that no essential feature should be omitted." But in June he wrote to the Department of the Interior that the east slope of the Chilkat Range along Lynn Canal, the Gustavus forelands, and the Lituya Bay area should all be excluded if it would otherwise "cause injustice to the settlers." [17] By then, Cooper apparently knew who the Interior Department had selected to survey the area, and the choice did not augur well for the national monument.

The man that Secretary Work sent to Glacier Bay was George A. Parks. Shortly to be appointed Alaska's next territorial governor, Parks had been in the territory since 1907 working for the General Land Office. He began his career as a field agent surveying coal claims, and had recently been appointed assistant supervisor of surveys for Alaska. Knowledgable about Alaskans' attitudes toward land and the federal government, Parks knew how to recognize potential mineral and agricultural areas when he saw them. [18]

Parks canvassed homesteaders, fox farmers, miners, and foresters about the natural resources contained in the area. His report, submitted in August 1924, consisted largely of an inventory of the area's economic potential according to the most liberal estimates. The boundaries of the temporary withdrawal embraced about one-tenth of the land area of southeast Alaska and practically all of the public domain in that region outside of the Tongass National Forest. Some four billion board feet of marketable timber stood along the 600 miles of shoreline. There were numerous islands within Glacier Bay which were suitable for raising foxes for the fur market; some were already developed. The area contained several patented homesteads, mining claims, canneries, fish traps, and Native allotments. The Gustavus forelands contained the only large area of agricultural lands in southeast Alaska, estimated roughly at 90,000 acres. The federal government had already surveyed about a quarter of that and was actively "extending wagon roads through this land to aid in its development." The creation of a national monument would be tantamount to confiscation of these inholdings, Parks argued, because they would be rendered valueless if the communities could not grow and obtain schools, transportation links, and mail delivery.

Parks spoke for prevailing Alaskan opinion when he concluded that the area did not merit preservation as a national monument in any case because human activity could not deface glaciers. Such was the limitation of monumentalism as a basis for preservation. The Ecological Society's slightly more subtle assertion of biological values failed to make much impression. Parks concluded that the "glaciers and other objects of interest," if they must be preserved in a national monument, could be segregated from the areas that were "potentially very valuable for future development." He proposed a boundary that enclosed the East and West Arms of Glacier Bay and the surrounding drainage, but omitted all of Glacier Bay from Geikie Inlet and Mount Wright to Icy Strait, as well as the far slopes of the flanking Fairweather and Chilkat ranges. [19]

After Parks submitted his report, it was clear to Cooper that the Coolidge administration's final decision on the national monument was near at hand and probably depended on another concerted effort by conservation organizations to tip it in favor of preservation. The Ecological Society's Committee on Preservation of Natural Conditions launched a second letter campaign, which brought the biggest flood of support for a new national monument or park that Park Service officials had ever seen. This support was vital in buttressing Park Service representatives as they met with their counterparts from the much more powerful Forest Service and Geological Survey. Using Parks's restricted boundaries as a basis for negotiation, the agencies worked it out in closed conferences with Alaska Territorial Delegate Dan Sutherland during December 1924. [20]

The Geological Survey posed the greatest challenge, opposing any reservation that would prohibit mining. Sutherland offered to introduce a national-park bill in Congress specifically authorizing mining, as in Mount McKinley National Park. Chief Forester William B. Greeley proposed the creation of a national monument or recreation area under Forest Service jurisdiction. The Park Service stood firm against all of these proposals. Cooper and his three fellow committee members perceived a stalemate, and went to Assistant Secretary Edward C. Finney on January 2, 1925 "in a state of complete discouragement." To their surprise and relief, Finney intimated that Secretary Work would recommend to the President the establishment of a national monument with mining prohibited. Immediately after this conference, Finney informed the Park Service of the coming proclamation. [21]

Cooper made one last appeal for the preservation of some mature forest within the national monument. On January 8, he wrote to the Department of the Interior that the Ecological Society was "exceedingly desirous" that the national monument include an area south of Mount Wright "for the preservation of certain features of great scientific interest, and for the provision of a suitable site for future administrative headquarters." This letter succeeded; President Coolidge's proclamation of Glacier Bay National Monument on February 26, 1925 described a boundary that followed Parks' recommendation, with the addition of the Beartrack Creek drainage and all the shoreline area between. [22]

The President's proclamation offered substantially the same purposes for the national monument as were expressed in the Ecological Society's resolution. The scenic values and accessibility of Glacier Bay were combined in the first clause; the second clause alluded to successional stages of forest covering; the third clause noted its scientific importance for glaciology and ecology; and the fourth clause, added by the Department of the Interior, cited the area's "historic interest having been visited by explorers and scientists since the early voyages of Vancouver in 1794, who have left valuable records of such visits and explorations." [23] Possibly this last clause was intended to underscore Glacier Bay's scientific tradition, but more likely the phrase "historic interest" was chosen to stake the President's proclamation more squarely within the bounds of the Antiquities Act.

Cooper and others who had worked hard in the campaign could take pride in their accomplishment. The boundaries, though disappointingly constricted, were perhaps the best that could be achieved on behalf of science and monumentalism. Monumentalism emphasized the gargantuan physical features of Glacier Bay to the detriment of biological diversity. The needs of science were somewhat more inclusive, but science then did not command the respect in American society that it holds today. It was unusual that scientific values were noted by the proclamation at all. The establishment of Glacier Bay National Monument in 1925 was fundamentally a compromise between preservationists and developers.

|

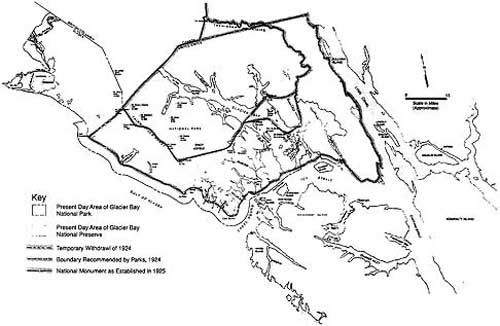

| National Monument Boundaries (1). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

A Refinement of Conservation

If George Parks had intended to screen every last economic enterprise from the national monument in his survey of 1924, the General Land Office soon heard that he had missed one. Possibly the lone enterprise sprouted inside the proposed monument shortly after Parks conducted his field survey, for Joe and Muz Ibach, residents of Lemesurier Island in Icy Strait, went prospecting for gold some time during the early summer of that year in Reid Inlet. About 2,000 feet above the Reid Glacier terminus Joe struck a gold-bearing vein. Farther up the valley at 1,000 feet elevation he struck another. [24] The Ibachs staked their claims and registered them later that summer, uninformed by the clerks in the Land Office that the area had been temporarily withdrawn from entry by President Coolidge's executive order of April 1, 1924.

After Glacier Bay National Monument was established, the Ibachs learned that they could not work their claims. "If I moved a stone or stuck a pick in the ground, they said I'd be defacing the park and it would constitute a trespass," Joe Ibach later complained. At the same time, the mining law required them to do $100 assessment work every year to maintain their claims. The Ibachs wrote Alaska's territorial delegate, the Department of the Interior, and other agencies, but they could not get their title assured. Finally the Ibachs bought a small, gasoline-powered portable stamp mill, built a shack for it on Lemesurier Island, and began bringing ore out of Reid Inlet by the sackful. "Muz and I steal off up there when we can and bootleg the ore out, like a couple of burglars. Our own ore! Imagine it!" Joe told his friend Rex Beach. [25]

Rex Beach was a popular writer of Alaskan adventure stories who lived in Florida. Joe Ibach had met Beach thirty years earlier on a bear hunt in southern Alaska. According to Beach, the friendship lapsed until one day in 1935 Beach received an invitation from the Alaskan prospector to come renew their acquaintance, publicize the Ibachs' story, and get the national monument opened to mining. In view of Beach's subsequent lobbying efforts and financial investment in Joe Ibach's claims, however, it seems likely that Beach was grubstaking Joe all along. Curiously, no one ever questioned Beach's motivation for diving precipitously into the politics of conservation.

Beach left his Florida home in 1935, traveled to Juneau, and chartered a seaplane to Lemesurier Island. Talking with Joe and Muz, Beach hit upon the idea of putting Glacier Bay National Monument at the tip of a much bigger scheme to ameliorate the Great Depression. "My idea was to set the thing up as a relief project," Beach wrote, "aimed primarily at young men, and offer a sort of government grubstake to able-bodied industrious young fellows who wished to become miners." Elaborating on his plan to Alaska Governor John W. Troy a short time later, Beach suggested that U.S. Army pilots could photomap Alaska as part of their flight training, the Geological Survey could then analyze the aerial photos, and the government could direct prospectors to the most likely gold-bearing streams. For an economy burdened by overproduction in both the manufacturing and agricultural sectors, Beach argued that gold was the ideal commodity to get things moving again. Glacier Bay, because of its marine access, would be the most advantageous place to begin the relief effort. [26]

Beach tried to stir interest among merchants, mining companies, and newspapers in Juneau, and, after returning to Florida, peddled his idea to Cosmopolitan. There was a gold rush in Alaska waiting to happen, Beach argued in the popular magazine, and all it needed was a helping hand from the government. After Beach's story came out, Alaska Delegate Tony Dimond introduced a bill in Congress to open the monument to mining. Assistant Secretary of the Treasury L.W. Robert invited Beach to discuss the plan in his office with Dimond and Philip Smith, Alaska chief of the U.S. Geological Survey. Smith stated that his agency would indeed be able to make effective use of aerial photographs.

Beach thought these men were jumping on his bandwagon; more accurately, they saw Beach's article in Cosmopolitan as a hook for reversing the decision of eleven years earlier on mining in Glacier Bay National Monument. Smith probably had a personal recollection of that contest; his predecessor, Alfred Brooks, had died suddenly at the end of 1924 as the matter of the monument was coming to a head, and Smith had succeeded to his post a month after the proclamation. Smith was undoubtedly aware of recent correspondence between Alaska Governor Troy and the Geological Survey about his agency's official position on the subject of mining in Glacier Bay. The Geological Survey had a strong interest in opening the national monument to prospectors. [27] As for Delegate Tony Dimond, he had no desire to see thousands of unemployed men from the states flocking to Alaska at government expense, but if that kind of imagery could get votes in Congress, then he was not opposed to it.

Three days after Dimond introduced his bill, Park Service director Arno Cammerer wrote to Dr. William S. Cooper for his opinion on the impact mining would have on the purposes of the national monument. The ecologist replied emphatically that large-scale mining activity, which was what the proponents of the bill envisioned, "would work havoc upon the biological features of the region." The miners would cut whatever young growth of trees they could find and kill the scarce game that was coming into the area. If Glacier Bay indeed contained rich mineral deposits, and stamp mills were shipped in for milling the ore, the resulting development "would utterly defeat a large part of the purpose for which the Monument was created." [28]

Arno Cammerer exchanged letters with Beach in mid-January 1936 after Secretary Harold Ickes gave the novelist a particularly cold reception in his office at the Department of the Interior. Apparently Ickes was the first official to call Beach's plan what it was: a smokescreen for a raid on protected public lands. But opposition by the Park Service and Ickes did not prevent Beach from getting a hearing from President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House on January 15. Evidently some people in the Roosevelt administration were friendly to his scheme. Beach found the President amenable to his plan. Roosevelt seemed to be familiar with the magazine article, and pronounced the plan worthy of study. [29]

The few fleeting occasions when Roosevelt gave his attention to this problem were decisive, and yet the President's position in support of the bill left opponents of the measure like Cooper groping for ways to understand him. Cooper suggested that Roosevelt was carried away by the thought of another large outdoor relief project; after all, he had more than a million young men working in the woods under his own brainchild, the Civilian Conservation Corps. After his meeting, the President jotted a note to Secretary Ickes: "Rex Beach says that if we open Glacier Bay National Monument for prospectors thousands of unemployed will immediately go there on grub stakes." [30] Clearly he saw this bill as an emergency economic measure, but it was more of a search for the old frontier safety valve than another attempt to combine conservation with social engineering. The solitary, hardscrabble business of prospecting hardly matched the nurturing social environment that the Civilian Conservation Corps sought to provide, and it seems doubtful that Roosevelt reacted to Beach's plan in this vein.

It is more likely that Roosevelt simply agreed with Rex Beach that a scenic landscape composed mainly of water, ice, and rock would not be harmed very much by a mine adit here or a sluice box there. Roosevelt commented further to Ickes on January 15 that the monument was "wholly unfit for habitation," and he could not see how mineral development could seriously impair the scenery. As for the threat to wildlife from so many prospectors, the Park Service could prohibit firearms in the area. [31] Roosevelt's argument seemed to counter Cooper's main points so closely that he must have been apprised of them, either by Cammerer or more indirectly by Beach.

In February, the chairman of the House Committee on Public Lands referred Dimond's bill to the Department of the Interior for a report. Informed by Cammerer that the administration's position on the bill was vacillating, Cooper realized that the Ecological Society of America had to mobilize a defense of the monument. He reactivated the committee on Glacier Bay, went to New York and Washington for meetings with conservationists and NPS officials, and started another letter-writing campaign. [32] The Ecological Society endorsed the Park Service's recommendation that no bill should be passed pending a mineral survey of Glacier Bay by the Geological Survey in the coming summer. [33]

The response by conservation organizations and concerned citizens surpassed the support given to the earlier campaign in 1924. More than 150 letters were sent to the White House, the Department of the Interior, and members of the House and Senate committees on Public Lands. [34] As a result, Secretary Ickes reported negatively on the Dimond bill and it died in committee. The most important criticism of the bill, which Roosevelt cited to Dimond in a letter drafted by the Department of the Interior, was the bad precedent it would set for other lands in the national park system. [35]

Roosevelt, however, raised the issue again on May 4. Prompted by a letter from Beach, he wrote to Ickes:

I must say I am inclined to agree with Rex Beach in regard to actual mining prospecting on your glaciers in Alaska. It seems to me a refinement of conservation to prevent mining on a glacier. Any scars on the face of nature would be infinitesimal in comparison with the magnitude and grandeur of the National Monument, and, in any event, nature would obliterate mining scars up there in half a generation. To wait until the Bureau makes a complete geological study and report may mean waiting until everybody now alive is dead. The Bureau has no money or plans for such a survey anyway. Let us cut red tape and get the thing started. [36]

Ickes had to swallow hard. Someone in the Department of the Interior--it is not clear who--planted the fiction with Robert Sterling Yard of the Wilderness Society that the President instructed Ickes "to make no protest against this bill," as if the Administration was yielding to the will of Congress. [37] In fact, under Roosevelt's goading, the Department of the Interior redrafted Dimond's earlier version and called upon Senator Lewis Schwellenbach of Washington to sponsor it. Dimond was notified about the President's position so that he could reintroduce his bill in the House.

Dimond and Schwellenbach both introduced their bills on June 16, the first day of a harried week of legislative action sandwiched between the Republican and Democratic Party national conventions. Senator Key Pittman of Nevada, a staunch Roosevelt loyalist, arranged a hearing for the Senate bill before the Committee on Public Lands the next day, June 17. Armed with a favorable report by the secretary of the interior and a unanimous recommendation by the committee, Pittman told the full Senate on June 18 that the bill was an "emergency matter" that required prompt action or an entire year would be lost. He misrepresented the size of the national monument as a modest fifty square miles and said that efforts had been made for the past ten years to open it to mining. He reported that the barren terrain did not support much wildlife and could not be "defaced or denuded by human agencies." [38] Without further discussion, the Senate sent its version to the House. The House substituted the Senate bill and passed it on June 19, and the Senate passed it on June 20. Roosevelt signed it into law on June 22.

In redrafting the bill, the Department of the Interior added an important safeguard: mining operations in the monument would be regulated by the department in such manner as to protect surface areas from undue damage. The department's special mining regulations for Glacier Bay National Monument, formulated that summer, restricted timber-cutting to the area of the claim, banned firearms, and prohibited road construction without permission by the Park Service. The law proved to be ambiguous on one issue, however, which would arise many years later. It was unclear whether Congress intended the act to assure mining claimants the right to mill ore on the surface if on-site milling was the only economically viable method of extracting the ore. [39]

Conservationists were outraged by the Act of June 22, 1936, believing that it had been pushed through Congress surreptitiously. Cooper organized a committee of eight representatives of leading conservation organizations to consider possible countermeasures. The committee published a blistering account of the episode in the National Parks Bulletin. But the committee soon recognized its powerlessness to get the law repealed, and turned instead to "making the best of an unfortunate situation." [40]

The Saturday Evening Post ran a stinging editorial under the heading "Why Have Any Principles?" The writer bemoaned the precedent of allowing mining within a national monument.

If an area is sufficiently unique from the scenic, aesthetic, historical or scientific viewpoint to make it a national park, it is of more value for that purpose than for any other. If an area is properly chosen for national park use, then that is its highest possible use, and not some other. It is difficult to understand this invasion of national park principles and standards....Let us be consistent about these matters. If areas are more important for mining, lumbering, grazing and agriculture, then let us keep them for that use. But there is something childish in setting aside these superb reservations as national parks for all time, and then letting down the standards. [41]

After Roosevelt signed the bill into law, the Geological Survey sent a man to Glacier Bay. This was hardly the photomapping and analysis that Beach had first proposed, nor even the $10,000 survey that the Park Service had requested before the national monument was opened to prospecting. But the Survey's J.C. Reed did identify eight localities where prospectors should begin their efforts. Ironically, only three of the eight areas were close to glaciers, two were in timbered areas, and one was on North Marble Island where seabirds nested. Three promising localities lay outside the national monument boundary. [42]

No gold rush ensued, and no one could claim after a few years passed that the Act of June 22, 1936 produced any measurable improvement in the economy of Alaska or the nation. The act failed, therefore, in its primary objective of emergency relief. On the other hand, conservationists' worst fears proved unfounded; the act was not precedent-setting for opening national parks to mining.

Ironically, most prospecting in the late 1930s and early 1940s was done by local residents like Joe Ibach, as they scratched out a living by farming, fishing, trapping, or raising foxes. The largest operation in this period was the Tlingit-owned Wolf Creek Mining Company's works at Sandy Cove. About twenty Hoonah Tlingits worked on the property in the mid-1930s, and when the company suspended work a few years later it had 103 feet of tunnel, a bunkhouse, warehouse, cable train, compressor house, and blacksmith house within sight of the water. [43]

Perhaps the greatest irony--or enigma--was the role played by novelist Rex Beach. As soon as the bill was enacted, Beach sent two discreetly worded cables to Joe Ibach, fearful that his messages would set off a gold stampede if they fell into the wrong hands; after all his effort, he did not want to lose out to a bunch of claim jumpers. Ibach went up to Reid Inlet and staked a total of forty-two claims for Beach and himself, ten on the east side of the inlet and thirty-two on the west. [44] The claims showed little promise after two years of work, and an NPS official recorded in 1938 that Rex Beach was "no longer interested in developing the claims." But a neighbor of the Ibachs stated that Joe took 30 tons of ore from Reid Inlet in 1939 and got $1,800 worth of gold concentrates from his stamp mill on Lemesurier Island. By 1940, Joe Ibach, Tom Smith of Juneau, and two other men had dug a 30-foot hole and built a cable tram nearly one mile long down to the beach for loading ore on a scow. The ore was smelted in Tacoma, Washington. [45] Rex Beach, in his book Personal Exposures, published that same year, stated that he never saw a dime from his investments in Glacier Bay. Such candor from a gold miner makes one wonder.

|

| Joe and Muz Ibach, in front of their Lemesurier Island cabin, 1954. (Photo by Bruce Black (NPS), in Bohn, Glacier Bay; the Land and the Silence, 96.) |

|

| Joe Ibach located a gold-bearing vein near Reid Glacier in 1924; he worked the claim, on an intermittent basis, through the 1940s. His cabin is shown at the right in this 1964 photograph. (Dave Bohn photo, in Glacier Bay; the Land and the Silence, 88.) |

|

| Abraham L. Parker's shack at the LeRoy Mine, September 1966. The site was on Ptarmigan Creek, between Reid Inlet and Lamplugh Glacier; activity took place there from 1938 until 1945. (Robert Howe Collection, photo GB 487.) |

|

| Stanley (Buck) Harbeson's homestead cabin, Dundas Bay, July 1967. Habeson erected his cabin during the 1930s and died there in 1964. (Robert Howe Collection, photo GB 702.) |

|

| The Yakobi at Reid Inlet, 1940. This ship, skippered by Tom Smith of Juneau, was used for the Harvard-Dartmouth Alaskan Expedition, a mountaineering and scientific effort that explored both Glacier Bay and the outer Fairweather Coast beginning in 1932. (Bradford Washburn photo, in Boh, Glacier Bay; the Land and the Silence, 85.) |

|

| During the mid-1950s, Kenwood Youmans (left) and Joe Ibach paused for a photograph at Ibach's homestead on Lemesurier Island. Youmans served as a park ranger (later a maintenance man) for more than 20 years, while Ibach was a miner who had lived in and around the monument since the 1920s. The photo was probably taken by NPS biologist Victor Cahalane. (GLBA Collection.) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2000