|

GLACIER BAY

Land Reborn: A History of Administration and Visitor Use in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve |

|

| PART TWO: HABITAT PROTECTION, 1939-1965 |

Chapter IV:

Alaska Brown Bears And The Extension Of The Monument

Glacier Bay National Monument began to be imbued with new cultural meanings almost as soon as it was created. As viewing of animal life, particularly big game, moved toward the center of many Americans' ideal of nature appreciation in the 1920s, people attached increasing significance to Glacier Bay National Monument as a wildlife sanctuary, a place where birds and mammals could thrive in their natural setting undisturbed by human activities. This natural setting, in the parlance of the new science of ecology, was called habitat. Park Service wildlife biologists determined in the 1930s that the most effective way to preserve park wildlife was to protect habitat. Thus national parks and monuments assumed prominence in the American people's growing demand for wildlife sanctuaries. It was primarily for the purpose of providing a sanctuary for the Alaska brown bear that President Roosevelt extended the boundaries of Glacier Bay National Monument to the outer coast and Icy Strait in 1939. Protection of habitat formed a new context for the administration of Glacier Bay National Monument.

Public Concern for the Alaska Brown Bear

In the 1930s, the Alaska brown bear became what modern environmentalists would call a "flagship species," a symbol and a cause that rallied public support while raising broader issues of public policy. As conservationists drew sharp comparisons between the threat to this animal and the near extinction of the buffalo in the nineteenth-century American West, the fate of the Alaska brown bear came to symbolize the question of whether modern Americans could live in harmony with nature or were bound to repeat in Alaska the mistakes of their frontier past.

At issue was a revision of the Alaska game law that critics claimed would lead to a campaign of extermination against the brown bear. Congress had established a game law for the district of Alaska in 1908, but it was widely abused. In 1925, Congress had revamped the game law and created a regulatory Alaska Game Commission, with a view to winning local acceptance of the law and making it enforceable. One section of the law that continued to chafe Alaskans, however, was the closed summer season on brown bears. After much deliberation, the Alaska Game Commission loosened the law's regulations in 1930 to eliminate the closed season for Alaska residents except in designated reserves. Within the reserves, residents were limited to two bears in season. The Alaska Game Commission further loosened the regulations by stipulating that residents could kill bears anywhere at any time of year if they deemed them a threat to life or property. This "loophole" appeared to the law's critics as a license for slaughter; to its defenders it was merely taking into account human nature.

Conservationists pursued two strategies in rallying opposition to this revision of the Alaska game law. First, they represented Alaskans as gun-happy frontiersmen who, given the opportunity, would kill bears indiscriminately and drive them to extinction. The most effective spokesman for this point of view was renowned nature writer Stewart Edward White, who predicted that the new regulations, if allowed to stand, would mean "our unique brown bear of Alaska is doomed to as complete extinction as the California grizzly." White entered the fray with an article in the April 12, 1930, issue of the Saturday Evening Post, urging his readers to demand from their senators and representatives better protection of the Alaska brown bear. This line of attack naturally provoked many Alaskans, who insisted they had as much stake as anyone in preserving the brown bear, since the animal lured so many wealthy sportsmen to Alaska. Yet there was some truth to White's characterization of Alaskans. A southeast Alaskan newspaper editor was reflecting widespread sentiment when he wrote, "The only answer to this damnfool law is to kill everyone of the darned grizzly pests that stick their hides within gunshot distance." [1]

The second strategy employed by conservationists was to argue that bears were victims of humans' misconceptions. They were not dangerous animals if treated with respect, and they did not stand in the way of progress. More than that, they were wonderful creatures whose extermination would be the nation's loss. These were the central ideas in a book on Alaska's grizzlies by John M. Holzworth which came out in the fall of 1930. Holzworth had spent three summers in Alaska stalking bears with a movie camera, and he filled his book with still photographs and descriptions of bear behavior. A New York lawyer and sportsman, Holzworth hoped his experience would inspire kindred spirits to convert to wildlife photography. "It affords a much greater thrill," he wrote, "and one is soon weaned away from the rifle, with beneficial results both to the hunter and to what remains of the fast dwindling big game animals of the wilderness." [2]

Holzworth had spent the better part of his time in Alaska on Admiralty Island, a rugged land mass about 100 miles long and twenty miles across, located about forty miles southeast of Glacier Bay. The island supported a large population of brown bear; indeed they easily outnumbered the Natives, who called the island Kootznahoo, or Bear Fort. Admiralty Island was already known by mammalogists from the work of C. Hart Merriam, who claimed that no less than five species of grizzly and brown bear inhabited the island. (Merriam's taxonomy included hundreds of species of bears altogether.) Holzworth accepted Merriam's classification, and estimated the island population at around 3,000, or approximately half of the world's total stock for these five species. Holzworth formed a committee for protection of Alaska's grizzlies, and secured resolutions and endorsements from the New York Zoological Society and the American Society of Mammalogists recommending that Admiralty Island be preserved as a wildlife sanctuary or national park. [3] Several editors of outdoor magazines gave their active support. A.N. Pack publicized his two "hunting" trips with camera to Admiralty Island and kept the issue before the readership of Nature Magazine. Harry McGuire, editor of Outdoor Life, aimed a fusilade of caustic articles against the Alaska Game Commission. [4]

Alaska game managers received scores of letters in support of a bear sanctuary, mostly from people who had never been to Alaska and probably did not expect ever to go there. Newspaper editors all over the United States chimed in. [5] The U.S. Senate formed a special committee on conservation of wildlife resources and its chairman, Senator Frederic C. Walcott, went to Alaska in the summer of 1931 to investigate continuing reports of brown bear slaughter. In December Walcott told the Eighteenth American Game Conference in New York that the bear population was definitely declining "in several of its most important habitats." That same month, Holzworth gave a series of radio talks over the NBC network. [6] Obviously, the Alaska brown bear had become something more than a trophy animal.

The reasons for this uproar were complex. Public sentiment about wildlife was changing under the influence of ecological and humane ideas. Such basic ecological concepts as the food chain and the niche were gaining currency, giving greater substance to old assumptions about the "balance of nature" and "web of life." [7] Clearly Alaskan brown bears were high on the food chain and occupied an important niche in wild Alaska. Nature writers like Stewart Edward White invoked these ideas when pointing out the foolishness of killing bears because they competed with fishermen for declining salmon harvests. Bears had been consuming salmon for millenia, and it was human, not bear, activity that must be changed.

In another vein, humane ideals espoused by new organizations like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the American Humane Association encouraged a more sentimental view of wildlife. One writer asserted that brown bears were "among the most attractive and entertaining of extant beasts," and a senator eloquently stated the humane point of view in a special hearing on the Alaska brown bear when he declared, "I think it bespeaks the dawn of a new day when the tourists and wild life can live together...for the benefit of human beings who can use them without abusing them." [8]

Public confidence in the government's game managers was low. For some years animal ecologists in universities had been attacking the efficacy of government wildlife programs, especially the Biological Survey's use of poisons for predator control. Even government biologists were questioning their own methods. According to the old thinking, game populations could be increased for the benefit of sportsmen when predators like the wolf, coyote, and cougar were eradicated. The new thinking, based upon ecological principles, cast predators in a different light. If predators were exterminated, the prey species would become too numerous for the land to support. Then there would be mass starvation and the population would fall below what it had been when the predators were around. Precisely this scenario had occurred on the Kaibab Plateau near the Grand Canyon, and the appalling condition of the Kaibab deer a few years after all mountain lion were eliminated came to symbolize for these wildlife biologists the danger of tampering with ecological relationships.

The reversal in thinking about predator control was so new in 1930 that conservationists suspected the responsible agencies of double-talk whenever officials claimed to support preservation of Alaska brown bear. Some conservationists accused the Forest Service of secretly slaughtering brown bears on Admiralty Island so that the Crown Zellerbach Company would launch a major pulpwood operation there. For evidence, they cited a seemingly duplicitous letter from the Tongass National Forest's forest examiner, Jay P. Williams, in which he warned that it would be poor public relations to espouse extermination of the brown bear, while at the same time he offered two methods for accomplishing it--hunting them above timberline in early spring, and using poison bait when they congregated for the salmon runs. Foresters insisted that the letter was quoted out of context. The chief forester in Alaska co-authored a bear management plan for Admiralty Island that purported to show how bears and a pulping industry could coexist. One forester testified before the Senate committee on wildlife resources that displaced bear could move back into second-growth forest in the wake of timber operations. "I think it will be entirely possible and proper to cut this timber and at the same time raise bear in the woods." [9]

Conservationists also attacked the Alaska Game Commission with charges of indifference, even collusion. Outdoor magazines reported persistent rumors of unsporting slaughter. It was said that hunters were shooting bear from yachts. The Alaska Game Commission offered records showing that reported bear kills for all of Alaska ranged between 123 and 145 per year--certainly not enough to threaten the bear population; but it was the unreported kills that were causing alarm.

Indeed, a lack of information made it impossible either to prove or disprove the allegations of slaughter. Game managers in Alaska were probably correct when they claimed that the Alaska brown bear population was stable or even rebounding, thanks to the closed season operating since 1925. They simply lacked credibility to get that message out. When they touted the 47,033 square miles already set aside as brown bear reserves, some conservationists called them "game farmers" and insinuated that they only wanted to grow animals for sportsmen to shoot. "A Nature sanctuary," one conservationist wrote, "should be an area where Nature, not certain elements of it only, but all Nature, is sacred from interference." [10]

Alaska's embattled game managers approached the Park Service with a proposal to extend the boundary of Glacier Bay National Monument and make it the bear sanctuary that the public demanded. The area surrounding the national monument--essentially the area described by Cooper and deleted from the national monument on the recommendation of George Parks--had been added to the Tongass National Forest by executive order in 1924 and 1925. The Alaska Game Commission had designated most of this northern extension of the Tongass as the Glacier Bay bear reserve in 1925. As early as 1927, the chief of the Biological Survey proposed that the reserve be added to the national monument. Initially the Forest Service balked at this. Assistant Regional Forester B.F. Heintzleman and other foresters envisioned future marketing of the large coastal spruce and hemlock forest around Lituya Bay. Now that conservationists were agitating for a sanctuary or national park on Admiralty Island, however, the Forest Service changed its attitude. It could forfeit this northern extension of the Tongass in order to safeguard the pulpwood interests on Admiralty Island. [11]

The Park Service Gets Involved

Amidst the growing clamor for bear protection, the Park Service initially maintained a dignified silence. It was the Alaska Game Commission, the Biological Survey, and the Forest Service that were taking heat, and Park Service officials were content to let those agencies strenuously remind the American public that bears were fully protected in Mount McKinley, Katmai, and Glacier Bay.

Probably another reason that the Park Service did not immediately get involved was that the agency was wrestling with its own philosophy of wildlife management. As late as the 1920s, national park managers did not manage wildlife any differently than wildlife managers of other public lands did, where predators were treated as varmints--shot, trapped, or poisoned. The ruling logic was that predator control increased populations of deer, elk, and other big game that tourists liked to observe in the parks and sportsmen liked to hunt outside the parks; therefore the interests of the Park Service and the Biological Survey coincided. This began to change under the influence of a survey of wildlife in the national parks initiated and funded by a young, independently wealthy park naturalist named George M. Wright. Wright hired two friends to assist him: Joseph S. Dixon, an assistant professor of biology who, like himself, had been trained by the ecologist Joseph Grinnell at Berkeley, and Ben H. Thompson, a recent Stanford graduate whom Wright met in Yosemite. The three men launched the project in 1929. After two years, the preliminary results of the park wildlife surveys so impressed director Horace Albright that he instituted a series of reforms, beginning with the announcement of a new NPS predator policy in the May 1931 issue of the Journal of Mammalogy. Albright expanded the agency's research arm, giving greater scope and financial support to the wildlife biologists. In May 1932, Wright, Thompson, and Dixon completed their ground-breaking study of wildlife ecology, Fauna of the National Parks of the United States. [12]

This study, together with four more studies in the fauna series, laid the foundation for a profound reorientation of wildlife policy in the 1930s. The central goal of the new policy was to restore natural faunal relationships within the national parks and monuments. As the science of ecology developed, Wright, Dixon, Thompson, and others refined this important goal of NPS policy to embrace the restoration of a particular kind of natural system: the North American environment as it looked before the advent of American civilization.

In Fauna of the National Parks the authors baldly stated, "A park is an artificial unit, not an independent biological unit with natural boundaries....The boundaries, as drawn, frequently fail to include terrain which is vital to the park animals during some part of their annual cycles." Boundaries--and limited space--appeared to be the biggest challenges to the realization of their goals. The authors continued:

At present, not one park is large enough to provide year-round sanctuary for adequate populations of all resident species. Not one is so fortunate--and probably none can ever be unless it is an island--as to have boundaries that are a guarantee against the invasion of external influences. To all this the practical-minded will immediately retort that an area with artificial boundaries can never be a true biological entity, and obviously this is correct. But it is equally true that many parks' faunas could become self-sustaining and independent if areas and boundaries were fixed with careful consideration of their needs. Already many parks are being improved in this regard, and there is a vast amount more that can be done. [13]

It is easy to imagine Joseph Dixon's excitement, a few months after completing this work, when he drew the assignment to investigate brown bear habitat and recommend boundary revisions for Glacier Bay National Monument. It was an outstanding opportunity to put some of these principles into practice.

Accompanied by the chief of the Biological Survey and Assistant Regional Forester B.F. Heintzleman, Dixon overflew Admiralty Island and the outer coast by seaplane, and returned to Glacier Bay via the Forest Service boat Forester for a four-day inspection of brown bear habitat. The trip began on a clear September day, "one in a hundred, for this area at this summer season," Dixon wrote in his journal. [14]

Landing the boat and following bear sign into the alder thickets and spruce forest, the men explored Beartrack Cove, Bartlett Cove, Berg Bay, Dundas Bay, Point Carolus, and Excursion Inlet. Actual brown bear sightings were limited to one pair ambling across a grassy meadow in Beartrack Cove, but everywhere they found signs, including well-worn paths and beds in alder thickets around Berg Bay, and enormous tracks.

Dixon gauged the brown bear habitat and terrain both from the standpoint of the wildlife viewer and the bear population. At Beartrack Cove he found an ideal location that the Park Service could develop for brown bear observation:

At this point there is a unique opportunity to present Alaska brown bears under wholly natural conditions. There is a salmon stream and a stretch of open beach and a meadow where the bears wander about, with a strip of timber leading up to it so that one may approach to within 100 yards of the animals without being detected. In most instances, bears are found in brushy areas at the mouths of salmon streams where it is difficult for the public to get near them. [15]

The confined drainage around the cove was too small to support a large brown bear population, so it would be necessary to include adjoining drainages within the national monument. He wrote in his journal: "Alaska Brown Bears should have a good salmon stream in their refuge and the river at the head of Excursion Inlet and Bartlett River are both good." These salmon streams lay on the other side of a low divide, about 1,800 feet high. Alaska brown bears in other localities were known to cross divides of that elevation. Coupling the accessible viewing area at Beartrack Cove with good food sources on the Bartlett River and Excursion Inlet, Dixon made the inclusion of the Excursion River drainage the main focus of his recommendations. Dixon knew there would be a fight, because Heintzleman made it clear that the Forest Service valued the timber on the steep slopes around Excursion Inlet. [16]

Consistent with his purpose of designing a viable bear sanctuary, Dixon gave little attention to the outer coast. That region had outstanding scenic and recreational possibilities, but biologically it was separated from Glacier Bay by the Fairweather Range and the Brady Icefield. Based on what he saw from the air, Dixon thought the outer coast environment had fewer brown bear; the LaPerouse Glacier, which plowed into the surf about twenty miles south of Lituya Bay, cut off a migration route from the north so that any bear population between it and Cape Spencer would be a refugium. The area would also be remote and hard to administer from Glacier Bay. [17]

Finally, Dixon did not see much point in staking a Park Service claim to Admiralty Island. He was probably encouraged in this view by Heintzleman, if not his superiors in Washington as well. He was content with one pass over the northern end of the island, and on this basis judged that it was not "of national park caliber." [18]

All the momentum seemed to be in favor of the national monument's extension: both Governor Parks and the Biological Survey responded favorably to Dixon's report, the Forest Service had already indicated its support, and public calls for bear sanctuaries continued unabated. That it did not happen soon thereafter probably related to the general climate of uncertainty in Washington as Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Party swept to victory in the fall election amidst a deepening economic depression. The Forest Service's long-standing goal of establishing a pulpwood industry in southeast Alaska, with half the operation centered on Admiralty Island, appeared more doubtful than ever. The Crown Zellerbach Company had purchased an option to cut 1.6 billion cubic feet of timber in 1927, but the paper market had collapsed before Crown Zellerbach ever built the promised pulp mills. Since then, the Forest Service had been criticized for the giveaway price it had tagged on the Admiralty Island timber. When the Roosevelt administration took office in March, one of the first items of housecleaning in the Department of Agriculture was the cancellation of the government's timber sale to Crown Zellerbach. There were predictions that the new Congress would consider a national-park bill for Admiralty Island. Since the Forest Service's support for the extension of Glacier Bay National Monument hinged on heading off demands for a national park on Admiralty Island, this reversal stymied any agreement between the two agencies. [19]

Bureaucratic inertia stalled the issue for the next half-decade. Wildlife advocates brought the matter to President Roosevelt's attention in 1934. Roosevelt sent a note to Secretary Ickes, "If these bears come under your jurisdiction, will you please have the matter checked up? It seems to me that this kind of slaughter ought to be stopped." Ickes replied that his department had enlarged Katmai and planned a similar proclamation for Glacier Bay National Monument "purposely to give additional protection to brown bears." [20] Six months later Ickes sought the Department of Agriculture's consent to the extension; Agriculture sat on it for three months and finally recommended that action be postponed. [21]

In April 1937, a New York congresswoman again brought the matter of a national park on Admiralty Island to the President's attention, and Roosevelt directed the two departments to get together on it. Agriculture now insisted on postponing a decision until the Alaska Territorial Board, created by an act of Congress the previous month, could be established. This body (soon renamed the Alaska Planning Council) comprised four private citizens of the territory and five federal bureaucrats and was patently in favor of developing a pulp industry on the Tongass National Forest. Serving on the council was regional forester Heintzleman, who offered to cooperate with the Park Service in planning an extension of Glacier Bay National Monument in the hope that such action would finally put to rest demands for a national park on Admiralty Island. To work with Heintzleman on this new proposal, the Park Service selected its own chief of forestry, John D. Coffman. [22]

|

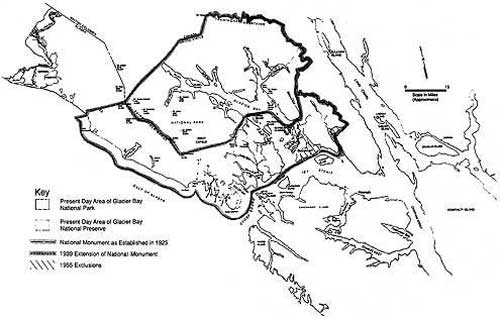

| National Monument Boundaries (2). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Tourism, Timber, and Brown Bears, Too

As the proposal to extend Glacier Bay National Monument gathered momentum again in 1938, two concerns relating to Alaska's economic future began to eclipse the issue of preserving bear habitat. Heintzleman and the Alaska Planning Council wanted assurances that the enlargement of the monument would enhance southeastern Alaska's prospects for attracting both tourists and pulp mill companies. Their goal was to gain national park status for Glacier Bay. Park status presumably would bring congressional appropriations for visitor services and on-site park administration. Also it would make Admiralty Island secure for timber harvesting. [23]

The Alaska Planning Council made it known that its support of the proposal rested on "definite assurance" that the new area would be administered and developed as a park. Specifically, the Park Service would need to provide visitor accommodations and some means of seeing the area, such as a tour boat. Heintzleman indicated that the Forest Service had plans to develop recreational facilities in the area if the Park Service was not interested. [24]

Dr. Ernest Gruening, then director of the Department of Territories and Island Possessions and soon to be appointed governor of Alaska, also spoke out for tourist development of Glacier Bay. Gruening visited Glacier Bay for the first time in September 1938. Enthusiastic about the spectacular mountain scenery from the Fairweather Range up the coast to Mount Saint Elias and inland to the Wrangell Mountains, Gruening suggested that the whole vast complex could be included within the monument. Park administration and visitor facilities might be temporarily developed in the languishing Kennecott Copper Company's works on the Copper River. Heintzleman's comment to Coffman on this scheme was that the Park Service could not develop two new areas at once, and if it wanted the Wrangell-Saint Elias region, Juneau businessmen would try to kill the Glacier Bay extension. [25]

Coffman and Heintzleman visited Glacier Bay together in July 1938. They were able to agree on most of the proposed new boundaries, with two exceptions. Heintzleman reiterated what he had told Dixon six years earlier, that he wanted the eastern side of Excursion Inlet retained in the Tongass National Forest for its valuable timber. He also expressed ambivalence about including the struggling settlement near Gustavus Point. The General Land Office had surveyed the latter area, as it considered the land potentially suitable for agriculture. A handful of homesteaders resided there, but the future of their community seemed doubtful. [26]

Even if Heintzleman did not change Coffman's mind about these two areas, he did succeed in reaching an understanding that the NPS would drop its support of a national park on Admiralty Island in return for his agency's cooperation. Coffman observed that the extension of Glacier Bay National Monument would accomplish two objectives at once: it would satisfy demand for a brown bear sanctuary and relieve the uncertainty of development for Admiralty Island. Joseph Dixon was even more explicit about this agreement when he warned against giving up the east side of Excursion Inlet:

I also wish to point out that a mutual agreement was made, and still holds as far as I am concerned, that in view of the concentration of the Park Service's efforts to secure adequate protection and sanctuary for the Alaskan brown bears in the Glacier Bay area rather than on Admiralty Island, it was understood and agreed that the Forest Service would give favorable consideration for all such needs in the Glacier Bay area. [27]

Coffman affirmed the linkage once more when he reported that the extension of the monument made it unnecessary to establish "any national park or national monument on Admiralty Island." [28]

Coffman and Dixon co-authored the Park Service's proposal, and the Wild Life Division's ecological guidelines shaped the final product. The aim of the proposed extension was to make the monument "into a biotic unit representative of the flora and fauna from the bare glaciers to the mature forests of the seacoast, and with the special purpose in mind of preserving the Alaska bears." The authors listed Alaska brown bear, three species of grizzly, black bear, and some of the rare blue, or glacier, bear as inhabiting the area. Regarding the latter, Coffman and Dixon stated:

The area here reported upon is considered by hunters to be as good for blue bear as any in Alaska. This species is limited to the glaciated coasts of Alaska and is eagerly sought for by hunters and museum collectors. This fact, together with its scarcity and the relative lack of scientific knowledge concerning it, emphasizes its need for protection.

The authors noted other mammal life: mink, marten, ermine, otter, lynx, red fox, wolverine, wolf, coyote, mountain goat, and Sitka deer. All of these were trapped or hunted and would need protection. The coyote and deer were both recent colonists. Whales, porpoises, and hair seal could be commonly observed in Glacier Bay and nearby waters. [29]

The strong ecological orientation of the authors was evident too in their forceful recommendation to include the surveyed lands near Point Gustavus. The small amount of farming and stockraising there created competition and conflict between humans and bears. Coffman and Dixon seemed to think these few residents would soon sell their holdings to the Park Service if the surrounding unpatented lands were included in the monument; otherwise, the community and the amount of human-bear conflict might grow. [30]

To make wildlife visible to the public, Coffman and Dixon envisioned that the Park Service would build a number of docks so that visitors could land at selected observation points for "viewing the bears when they are attracted to the salmon streams by the salmon run or for observing and studying other wildlife, vegetation, and glaciers." They reiterated Heintzleman's point that the Forest Service planned to develop the lower bay this way if the Park Service did not. [31]

Coffman's superiors in the Park Service responded timidly to his national park proposal. It was national park status, not the boundary extension, that made them pause. The problem, as Associate Director A.E. Demaray saw it, was that a park bill would have to address the special mining law of 1936, whose provisions applied to the new areas as well as the original monument. This would arouse vociferous opposition from conservation organizations. Demaray suggested to Secretary Ickes that the Park Service and Interior Department could "avoid criticism" if the boundaries were quietly extended by presidential proclamation instead. [32]

The Park Service subsequently prepared a proclamation for the President's signature, together with a letter of recommendation of the proclamation duly signed by acting secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture departments. The proclamation cited glaciers and other geologic features of scientific interest and made no mention of the controversial Alaska brown bear. With a stroke of his pen, on April 18, 1939, Roosevelt made Glacier Bay National Monument the largest unit in the national park system. The new boundaries conformed exactly to the boundaries proposed by Coffman and Dixon.

Curiously, Roosevelt and Secretary Ickes took another look at national park or monument status for Admiralty Island while these documents were in preparation. In mid-January they discussed with each other the future of Admiralty Island and Glacier Bay, and a few days later Ickes wrote to the President that the two areas could be combined administratively in one national park, with headquarters at Juneau. Less than a week before Roosevelt signed the proclamation extending Glacier Bay National Monument, he received a letter from Alaska Delegate Anthony Dimond, nervous about fresh reports that Admiralty Island was to be made a bear sanctuary. Roosevelt's reply shaded the truth. "It is my understanding that the Departments of Interior and Agriculture are considering the possibilities of Admiralty Island, along with other areas in Alaska, for addition to the national park and monument system. However, no recommendations have reached me." This letter, drafted by Interior for the President's signature, came to the White House together with a note from Ickes, informing Roosevelt that Interior would have a form for proclaiming Admiralty Island a national monument ready for his consideration in a few days. [33]

Ickes circulated a draft of the proclamation to the bureaus within Interior. The Park Service was embarrassed by the proposal. Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier did not even receive a copy, despite the fact that Admiralty Island was home to several hundred Tlingits. Ickes later apologized to Collier for his oversight. [34]

Although this draft proclamation apparently never went beyond Interior, Ickes' eleventh-hour deliberations over Admiralty Island nevertheless revealed his disingenuousness and penchant for bureaucratic infighting. The Forest Service had been led to think that it had an understanding; instead it faced more uncertainty. The settlers around Point Gustavus found their marginal homesteads subsumed in the monument with no indication from the federal government that their right to farm would be respected or that their land and improvements would be purchased by the Park Service. Members of the Alaska Planning Council might also complain of being hornswoggled; the extension of the monument was not accompanied by national park status, and Park Service plans to develop tourist facilities in Glacier Bay were soon set aside. Finally, there were the Tlingits whose hunting and fishing rights in Glacier Bay and Admiralty Island were virtually ignored throughout the entire process. Now those rights had to be considered. The extension of the monument boundaries in 1939 secured for the Park Service a wonderful area, what Joseph Dixon called "the greatest combination of examples of glacial history, plant and animal ecology and struggle for existence to be found in one place anywhere in Alaska." [35] But the enlarged domain left the Park Service with much fence-mending to do.

|

|

Carl Swanson was a fox farmer who relocated his

operations from Beardslee Island to Strawberry Island in 1929. They

remained active at the site until 1938. This 1965 photo shows his

Strawberry Island cabin, which has since collapsed. (Dave Bohn photo, in Glacier Bay; the Land and the Silence, 135.) |

|

| Senator Ernest Gruening, Huntington S. Gruening (one of the senator's sons), and W. Howard Johnson, USFS (regional forester for Alaska) are seen enroute to the Glacier Bay Lodge dedication, June 3, 1966. (Robert Howe Collection, photo GB 115.) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2000