|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Ranchers to Rangers An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site |

|

Chapter Four:

A HOME ON THE RANGE: FACILITIES DEVELOPMENT

By 1970, acquiring the ranch from Conrad Warren had been a long and tedious process during which no one had given much thought to just how the NPS would manage the area once the deed was transferred. Suddenly, the signing of the use agreement between Warren and the National Park Foundation placed full responsibility for the historic ranch zone squarely on the shoulders of the National Park Service.

As noted earlier, Yellowstone Park Ranger John Douglass, who had been the liaison for the ranch, identified an immediate need for a caretaker at the ranch. There was simply no other way to provide basic protection to the buildings, much less the thousands of historical objects on the property. He noted that a couple of mercury vapor lights were already extant on the grounds and there were lockable gates at the front entrance to the property. Douglass suggested that an employee "could live in a trailer below the old house where the ranch help had lived in a trailer in the past." And, more than just being there, the caretaker could perform minor maintenance and rehabilitation work on the structures. [1]

Douglass's recommendations late in 1970 led to the designation of Assistant Superintendent Vernon E. Hennesay as the key man for Grant-Kohrs Ranch until permanent staff could be hired. Hennesay inspected the site shortly after the Foundation purchase was concluded. He agreed with Douglass that a resident caretaker was required, but the conditions he found were worse than he had anticipated. A rock-lined spring approximately eight feet deep provided the only source of water, though Con Warren assured him it was potable. In the 1930s Warren had remodeled a few rooms on the second floor of the rear wing of the ranch house. These were used for several years by his ranch hands. However, Hennesay found the apartment in a sorely neglected condition and, worse yet, he discovered that the sewage was piped directly into Johnson Creek, only a short distance from the house. The electrical wiring in the ranch house appeared to be potentially dangerous and there were no storm windows covering the leaky original sash. The building, Con thought, still could be heated by the original coal furnace in the basement, but the cost would be exorbitant, to say nothing of the fire danger posed by the old furnace.

All things considered, Hennesay and Douglass concluded that placing a mobile home on the ranch was a more desirable and economical alternative. [2] Water could be piped from the ranch house and a sewer connection could be made with the city line running near the house from the treatment lagoon about a mile north. Leasing a trailer, however, turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. When Hennesay learned that the nearest source would be Salt Lake City, Utah, he managed to procure a spare trailer house from the inventory at Yellowstone and arranged to have it installed during the first week in December 1970. He also negotiated with the City of Deer Lodge for garbage collection, fire protection, and the sewer connection. [3]

Later in December, a maintenance worker from Yellowstone Park, Tom Pettet, was transferred to Grant-Kohrs Ranch. The forty-foot house trailer that had been provided for him was sited between the garage (HS-3) and the garden at the southwest corner of the yard. During a subsequent visit to help Pettet become established, Douglass noted the need for a telephone to be connected to the trailer because, in the event of an emergency, Pettet would have to go some distance to make a call. Too, if the caretaker was expected to do any maintenance work, he would need an assortment of tools because "all he has now is a ball peen hammer." [4]

Hennesay saw to it that the caretaker received a small cache of hand tools, brooms, and brushes. Pettet occupied his time by rehabilitating the shutters on the ranch house, making regular inspections of the property, cleaning the house periodically, and making his presence known in the community. Hennesay remarked that Tom, a Butte native, "seems to be fitting very well into the community and seems to get along well with Mr. Warren and his hired man." Although Pettet was anxious to do as much as he could, Hennesay reminded him that his primary function was to "keep an eye on the place." [5]

Pettet remained on-site until September 1971 when he was replaced by Ed Griggs and his wife, Jean, also employees of Yellowstone National Park. [6] This couple, occupying the same trailer recently vacated by Pettet, continued to fill the roles of maintenance staff, security force, researchers, and public relations team. The fact that there were two persons at the ranch was an inherent advantage.

The west portion of the basement of the ranch house (HS-1) was used as a primitive shop and office for the caretaker. Later in that year, probably in the fall, Hennesay brought a second smaller trailer from Yellowstone for use as an office. Although the residence trailer had a telephone, the office initially had none. Thus Griggs had to walk from the office to his quarters in order to use the telephone. This inconvenience was later corrected by the installation of an extension to the office trailer. [7]

|

|

Mobile home, used as employee housing,

situated alongside the thoroughbred barn. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

The first planning directive prepared for the area assumed that the park headquarters and perhaps even the maintenance operation would be in the ranch house. Just how those activities were to be accommodated in that building can only be speculated. Another objective was to establish limited employee housing on-site, with the remainder of the staff to reside in Deer Lodge. [8]

Vern Hennesay proceeded to identify no less than seventeen projects at the ranch that needed immediate funding. These priorities were submitted as high park priorities, but the 1976 National Bicentennial celebration, for which the NPS was the designated lead agency, took precedence throughout the System. Beyond having enough money to construct an access road to the meadows for Con Warren, thereby circumventing traffic around the historic zone, none of the projects were approved. "We all deeply regret that development of the area has not progressed more rapidly," a Department of Interior official wrote to Warren. "However, sufficient funds are not available to accomplish all the development projects within units of the National Park System." He went on to say that the community could expect a delay of two to three years before the Grant-Kohrs projects could be integrated into the system. [9]

Things at the ranch remained little changed until the park's first on-site manger, Richard R. Peterson, and Historian Paul Gordon arrived within a day of each other early in August 1974. They faced great challenges in a park that needed almost everything. Besides establishing a rapport with the community and giving momentum to the planning effort, a more practical need was to find a larger office space than that provided by the old trailer. The basement of the ranch house offered the only area large enough. The two decided to fire up the old coal furnace and to partition off a portion near the door with plastic sheeting, with the hope of surviving their first winter in Montana. They also acquired two desks and other basic equipment from the parent park. "We had a cold winter there," Peterson remembered. "The cold would come right up through your legs." If that were not enough, the basement lacked a ceiling and dust persisted in seeping through the floor above, covering everything in the makeshift office. Everything had to be covered with plastic sheeting when the office was not occupied. "It was pretty grim," recalled Gordon. [10]

Prior to their arrival, Hennesay had brought yet a third mobile home to the ranch, this one intended as additional employee housing. Peterson had been fortunate enough to locate a house in town for his family, but the Gordons moved into the trailer. It was situated immediately in front of the buggy shed (HS-17). He resided there until the spring 1976 when he too moved into Deer Lodge. The "New Moon" trailer Gordon vacated was then relocated alongside the thoroughbred barn (HS-15) where it remained. [11]

Prior to the arrival of the permanent staff, Hennesay had proposed that office space for park headquarters be leased in the city of Deer Lodge. The final decision was left to the new manager. Soon after Peterson arrived, it became obvious to him that the community was bent on getting the park open to the public, and money flowing into local commerce. He quickly became embroiled in the already heated issue of where to locate the park entrance, examined in a previous chapter. Faced with mounting public pressure to construct railroad crossings either on Milwaukee or Rainbow Avenues, Peterson championed an access directly from Highway 10, just outside the city limit. It was a more logical and much more economical entrance to construct than either of the other two alternatives. Besides, a picnic area desired by some citizens could still be developed on a parcel of land, known as Tract E, in the southeast corner of the site. "I see no advantage to be gained by locating our administrative offices in Deer Lodge proper," Peterson wrote. It was his opinion that if the access and attendant visitor facilities were developed on the 11-acre parcel south of the Warren residence, there would be no need to move into town. [12] Following public meetings on the environmental assessment in April 1975, the question was settled. Visitors would enter the park from the highway.

|

|

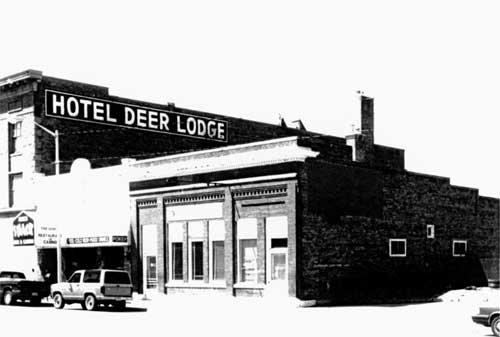

First park headquarters at 314 Main Street,

Deer Lodge. (Photo by D. McChristian) |

Before the area could host the public, however, Peterson saw an urgent need to install basic utilities systems. The agreement with the city to provide fire suppression services was fine as far as it went but Peterson recognized that a fire in a wooden historic structure would cause extensive damage, if not total destruction, in a matter of a few crucial minutes. The new park needed its own city water lines to supply both domestic needs and a network of fire hydrants in the historic zone. Electricity, too, was needed, along with public rest rooms. Additionally, there was the need to replace the old coal-fired furnace in the main house with a modern gas unit that would be both safer and cleaner to operate. The superintendent also wanted to see the intrusive trailers removed from the park. In order to do this, the old upstairs apartment in the ranch house had to be thoroughly rehabilitated for use as temporary employee quarters. Peterson also considered adaptively restoring one of the other buildings to house a permanent employee. [13]

Faced with the prospect of spending another winter in his dungeon-like basement office, Peterson conceded that moving the park headquarters to town would have some advantages after all. The probability of having a new visitor center with administrative space constructed anytime soon was extremely remote. Moreover, having an office right in the community could benefit the park's relationship with the townspeople. By August 1975 he and Gordon, augmented by a secretary and two maintenance personnel, were ensconced in offices at 314 Main. A maintenance shop was set up in the dairy barn (HS 9) at the ranch. [14]

Much of Peterson's attention was focused on the principal goal of gearing up for the public. Everyone wanted that -- the town of Deer Lodge, the Montana delegation, and the Park Service. The NPS had maintained custody over the property for more than four years, yet had very little to show for it. The agency was under pressure to demonstrate progress in a way that was evident to the public. As the result of continued political interest in the ranch, especially by local Congressman Dick Shoup, the planning schedule was advanced and the fiscal year 1975 budget was amended to include significant amounts for Grant-Kohrs Ranch development. In December 1974 NPS Director Ronald H. Walker informed the Montana senators that several line item requests of the park had been approved, including $105,000.00 for road planning and construction, plus additional amounts to install water and fire protection systems. [15]

With money available to construct a parking lot and trails, Peterson lost no time in pursuing these plans, following the spring 1975 announcement of the selected alternative. At issue was the development of a safe, efficient way for visitors to cross the two sets of railroad tracks dissecting the Site from north to south. These formed a major obstacle lying between the proposed parking lot and the historic ranch. Indeed, Peterson discussed design needs and cost estimates with both the Burlington Northern and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroads since shortly after his arrival. But, until the access location had been finally determined, these talks were only conceptual in nature. Once the decision was made, however, the NPS immediately requested the railroads to prepare detailed proposals and cost estimates for constructing the pedestrian underpasses. No one envisioned any particular problems with accomplishing this goal, apparently failing to consider that three bureaucracies were involved. In May 1975 "Pete" Peterson warned, prophetically as it turned out, that "bureaucracies move slowly." [16]

|

|

Nearly-completed parking lot, with visitor

contact station and restrooms. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

While negotiations continued with the railroads, work on the visitor facilities at the historic site shifted into high gear. The Denver Service Center, augmented by an engineer from Yellowstone National Park, coordinated with the fledgling Site to complete plans for the parking area, trails, and utilities. Unfortunately, the appropriation did not include funds for the design and construction of a visitor center, although some basic facilities were of necessity once the area was open for public use. Undaunted, Peterson and Peter Snell, a DSC architect, found two aging structures on the Cliff Benson Ranch (formerly the Kohrs-Bielenberg "Upper Ranch") that were architecturally compatible with the buildings at the Site. One, a "studs-out" granary typical of the Northwest region, embraced about 350 square feet. The other was a small unfloored log homestead cabin that Benson had used as a pig shelter. Thus, these buildings not only appeared much like those at the home ranch, they were associated with Kohrs. [17]

Peterson purchased these buildings and, using a flatbed trailer, had them moved intact to Grant-Kohrs where they were adaptively restored by maintenance workers Mike McWright and Arnold. Larson, based on Snell's plans. The granary, which retained a floor because it had been used recently for storing grain, was converted into a visitor contact station; the log cabin was converted into the public rest rooms. They were positioned adjacent to each other on a knoll near the northwest end of the proposed parking lot.

At the end of July, Peterson proudly announced that the buildings were in place and a "jack-leg" pole fence had. been erected along the north boundary of the parking area. Even more encouraging, the NPS had just awarded a package contract for installing the paved 28-car parking lot, trails, utilities, and paved walkways. Work started on the comprehensive project on August 11, 1975 and was finished by the end of October. The asphalt-paved trail leading from the parking lot to the ranch was built in two segments ending on each side of the railroad rights-of-way, since negotiations for the underpasses were still pending. [18] That fall also saw both the studs-out granary and the log cabin re roofed and wired for electricity. [19] Superintendent Peterson and his staff could be justifiably proud of their accomplishments that year. Grant-Kohrs Ranch NPS was finally beginning to take shape.

Nevertheless, the summer of 1975 had come and gone, and the ranch still was not open. It certainly was not due to any lack of enthusiasm or energy among the park staff They had done much within the short time they had been there.

The missing key to unlocking the ranch to public access was the pedestrian underpasses beneath the two railroads. But, the railroad companies seemed to be in no hurry. "The public expects us to open this summer . . . We have been talking about it for years and everyone is becoming a little impatient," Peterson wrote to a Burlington official. [20] The two companies had insisted that the design and construction of the facility would be done by their own engineers in order to meet critical railroad standards. There was also the question of the railroads granting rights-of-way to the NPS for the trail crossing. These approvals took more time than the Park Service anticipated, consequently the documents were not drafted until the spring of 1976. [21] However, the revised grading requirements stipulated by the NPS further slowed the process.

|

|

Construction of Milwaukee Railroad underpass,

1976. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

An impatient Peterson was presented with a serendipitous opportunity to employ some political pressure when the Secretary's Advisory Board scheduled a visit to the Site in June. Accompanying the group was William J. Briggle, the NPS deputy director from Washington. During the few hours that the Board members were on-site, Peterson found. the opportunity to brief Briggle on the seemingly endless postponements imposed by the railroads, particularly the Burlington Northern. With nearly everything else in place for public access to the park, it was frustrating and. embarrassing for the staff to be unable to explain the delay. After Briggle returned to Washington, he laid the groundwork with Senator Lee Metcalf's office to prepare an inquiry, ostensibly initiated by the senator, into the failure of the NPS to open Grant-Kohrs Ranch. This gave the NPS an opportunity to respond with a formal explanation of the problem, which served as a catalyst for Metcalf to tweak the Burlington Northern. [22]

Although the agreement with the Milwaukee Railroad was signed in July, the Burlington Northern dragged its corporate feet for more than a month. Milwaukee officials informed the Park Service that they would. begin construction in September 1976. The Burlington Northern once again cited lengthy delays. It would take months to obtain materials, they said, and. that would carry them into winter. By that time, the ground would be frozen so that pilings could not be set. It would be April 1977, at the earliest, before they could complete their underpass. Still, the optimistic park staff held out hope that both underpasses might be completed earlier. [23]

It was not. True to form, the Burlington Northern put off starting work until near the end of March 1977, well after the Milwaukee Railroad had completed its share of the project. [24] The end in sight, at last, a weary Superintendent Peterson issued bid invitations to complete the trail work and informed the Deer Lodge community that he was still hoping for a June 1 opening. This would be followed by a dedication ceremony in July. Even though the Burlington Northern completed its underpass in May, it still was too late for the park to open in June. The trail across the railroad corridor was yet to be finished, along with water and sewer line connections across the same easement. Once those connections were made, the park maintenance staff had only to put last minute touches on the contact station and rest rooms. Con Warren even provided a wooden flag staff which was positioned. near the contact station. In the interest of public relations, the park staff extended a special invitation to the Deer Lodge business community to participate in a special "sneak-peek" tour of the ranch during the first week in June. [25]

|

|

>Access trail beneath railroad underpass. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

The long-awaited formal establishment and opening of the area was slated for July 16, 1977. It was to be a grand. affair attended. by a plethora of politicians, NPS officials, Kohrs and Bielenberg family descendants, and Montana citizenry. Pete Peterson and his staff worked up to the final moments to ensure the success of the event. So close in fact was the completion of the contract work that, on the eve of the dedication, Peterson himself took rake in hand to help groom the newly laid gravel along the trail. [26]

Shortly after the dedication that he had worked so hard to bring to fruition, Peterson accepted a transfer to Washington, D. C., as a trainee in the Departmental Manager Program. This career-enhancing opportunity is offered to a limited number of employees with demonstrated potential for higher-level responsibilities. His three years at Grant-Kohrs had been a challenging, if not an often frustrating, time. But, he eventually reaped those "rewards of Park Service work." He and his staff had taken a park unit in its formative stage and through dedication, creativity, and hard work had brought it up to a basic level of operation. It would be up to his successors to consolidate and refine those gains.

With its foundation firmly established, the Grant-Kohrs National Historic Site was opened at last. Still, it had many critical needs when Superintendent Tom Vaughan arrived. in October 1977. Among those facilities-related matters yet to be overcome was that of providing an adequate water supply for both domestic use and for fire protection. The latter was vital, since the only water source available on the ranch was the spring-fed well, boosted by a 300 gallon-per-minute pump. At maximum pumping capacity, the well could supply water for only five minutes. The relatively small reservoir tank that had been acquired with the ranch had been sufficient for family needs, but was woefully inadequate for park requirements. Considering the high fire danger posed by nearly three dozen frame buildings, an appeal was made to program $209,000.00 in fiscal year 1978 to correct this situation. [27]

The funding did not materialize that quickly, but the project did. receive priority consideration late in 1979 when the old water source was condemned. [28] As a consideration for reducing resource impacts, it was decided to place all of the utilities, water, electric, and telephone, in a single trench. There was also a question that has plagued many historic sites: how best "to turn ugly old non-historic fire hydrants and hose housing into less intrusive features in the historic complex." Vaughan and others pondered this for some time. At last, the superintendent concluded that, "Anything we can think of to hide the fixtures is inevitably bulkier and more conspicuous than the objects to be hidden." Therefore, they would be left as they were. He did acknowledge that the hose house for the lower yard would have to be specially-designed by the park staff. [29]

The park would be supplied with water via a 10-inch line connecting with the city system a few hundred feet west of the railroads on Milwaukee Avenue. From there it would be buried in a trench along Park Street to a point where it would cross the boundary into park land. The line would traverse one of Con Warren's leased hayfields to a point south of the stallion barn (HS-14). The contract was let to Early Times Construction Company. [30]

This project, like many seemingly clear-cut park projects, quickly degenerated into a nightmare. Despite NPS warnings to the contractor prior to the bidding process, Early Times chose to ignore the high ground water conditions prevalent in the valley. As predicted, the trenching operation encountered water just 400 feet north of Milwaukee Avenue. Conditions intensified all the way to the ranch. The contractor's crew had to employ pumps for the entire time to reduce the water coming into the trench. To make matters worse, the contractor failed to use any sort of shoring in an already-too-narrow trench. The results were predictable. The crew fought flooding and collapsing trench walls nearly the entire 4,000-foot distance to the ranch. The project was still unfinished when Tom Vaughan departed for a new job at Harpers Ferry Center, late in July 1980. [31]

|

|

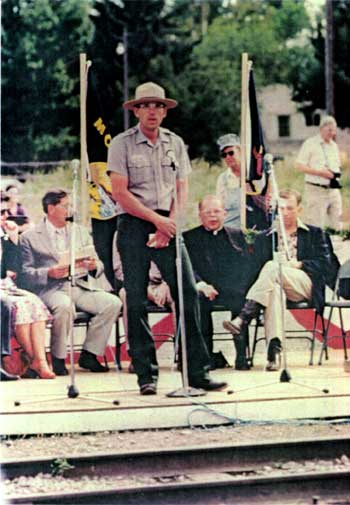

Superintendent Jimmy D. Taylor speaking at

Last Spike Centennial program, August 28, 1983. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

His replacement, Jim Taylor, arrived just after Christmas 1980, just in time to witness the testing of the new water main. The line leaked in several places where it had been pulled apart during construction, but those breaks were located and repaired rather easily. However, a particularly stubborn leak occurred somewhere between the stream crossing and the ranch house (HS-1). NPS staff advised the contractor to isolate portions of the line until the leak could be found, but he chose not to, unless a costly change-order were approved. That was declined, of course, because it was the contractor's responsibility to complete the line in a fully functional condition. This prompted the contractor to walk off the job, whereupon his lawyers took up the matter with NPS regional contracting officials. They made it clear that the contractor could either fix the line, or NPS would do so at his expense. The Early Times Company conceded defeat and a crew from Yellowstone Park was called in to assist Grant-Kohrs personnel in finding a solution to the problem. The leak was eventually attributed. to a mechanical connection, in which the Early Times workers had used incorrect bolts, near the ranch house. [32]

If that were not enough, Superintendent Taylor cited Early Times for failing to back-fill some of the excavated areas, failing to grade up around the hydrants, and failing to construct five hose boxes. Additionally, he discovered that fences had not been repaired and a final surprise disclosed that the line did not tie in to the plumbing at the ranch house. Early Times was not released until February 1981, yet two years later rocks were discovered in hydrant valves that had failed to function properly. [33]

In 1982 the entire National Park System benefited from a windfall in the form of the Park Restoration and Improvement Program (PRIP). Not for many years, since Mission 66 in fact, had the Park Service been blessed with so much funding to rehabilitate deteriorating park facilities, as well as to build new ones. Grant-Kohrs Ranch garnered money for two important projects: replacing the old coal furnace in the ranch house and installing a fire detection and intrusion alarm system. Also approved was a request for replacing the temporary electrical system that had been installed by the NPS years earlier. [34]

The first General Management Plan (GMP), which Tom Vaughan successfully shepherded to completion in 1980, envisioned the day when the Warren structures might be available for park use, though it left detailed planning to the future. Four years later, with the acquisition of the Warren property seemingly no closer than before, Superintendent Taylor submitted a revised request for a large, multi-purpose headquarters building containing visitor center, theater, administrative offices, museum laboratory, cooperating association, and public rest rooms -- virtually all of the park functions, except for maintenance. However, the regional office took a dim view of this grandiose proposal, advising Taylor that the central staff felt it was important to have agreement between the General Management Plan and the proposed facilities. "Your proposal goes beyond what could be conceived as a normal request in meeting your most urgent needs," wrote Associate Regional Director Richard Strait. He suggested that Taylor revise his request with minimum space requirements and, at the same time, pursue the purchase of the Warren buildings in the hope that a revised GMP would not be necessary. [35]

The eventual acquisition of the remainder of the Warren property, along with many additional buildings, in 1988 created new alternatives for the park. In the early 1990s, Superintendent Eddie Lopez recognized that the time was right to revisit those plans. His efforts resulted in a new, comprehensive document that envisioned the adaptive use of the Warren buildings. The main proposals of this still-current plan called for extensive modifications of the large red barn (HS-64) to house a spacious visitor center on the ground floor and park administrative offices on the second. Visitor parking was planned in a lot to be constructed nearby. The plan recommended that the "temporary" visitor contact station and rest rooms, still in use after more than two decades, be removed. A 12,000-square-foot curatorial facility is scheduled for construction on the same parcel. The main entrance to park would be moved farther north along the highway to the access road leading past the red barn, thus recreating an historic approach to the ranch house (HS-1). At the time of this writing, funding for the curatorial facility has been approved, but it remains to be seen whether the conversion of the barn will come to fruition.

Meantime, the Site has continued to cope with its principal operations widely scattered among several interim locations. The maintenance shop, for example, was moved from its first location in the dairy barn (HS-9) to the all-metal Warren sale barn (HS-65) in 1991. Administrative offices were moved in December 1991 from 314 Main Street in Deer Lodge to another and larger leased storefront at 210 Missouri Avenue, where they remain today. [36] And, the curatorial office, first located in the second floor apartment in the ranch house (HS-1), has resided in the Warren house (HS-58) since the winter of 1994-95, along with archival storage and the maintenance chiefs office. [37] Visitor reception, of course, is still conducted in the 1975 contact station, although the rest rooms in the adjacent log cabin were supplemented by the installation of another set installed in the 1930s blacksmith shop/garage (HS-3). This same structure has become the scene of multiple activities, including an audio-visual orientation program and blacksmithing demonstrations. [38] The continued dispersal of staff and functions, in the words of Jim Taylor, "continues to be a serious problem and a source of frustration for the staff." [39]

|

|

Park headquarters at 210 Missouri Street,

Deer Lodge. (Photo by D. McChristian) |

Neither has the issue of housing employees on-site been resolved. In 1975 the park maintenance staff rehabilitated the apartment in the ranch house (HS-1) so that it could be occupied by Park Technicians Ed and Jean Griggs during the following year. The mobile home they had been residing in was returned to Yellowstone Park in 1976. The one occupied initially by Historian Paul Gordon, and for many year since then by Park Ranger Lyndel Meikle, remains alongside the thoroughbred barn (HS-15). The ranch-house apartment was used as quarters for seasonal protection rangers into the early 1980s, when it was adapted for a time as curatorial offices, but it has not served in that capacity for many years. [40]

While the roads and utilities development at Grant-Kohrs Ranch have proceeded at what might be termed a normal pace, the visitor and staff facilities have not. This is not uncommon in historic areas where major line-item funding often lags far behind the opening of the park. The ranch in some ways has become a victim of its own enthusiasm through a quirk frequently witnessed in smaller park areas, especially those lacking a champion in Congress. Temporary facilities installed in the zeal to get a park moving all too frequently become long-term fixtures. Illogically, these minimal facilities tend to dilute the urgency of a site's need, thereby counteracting justifications for permanent replacements. Despite the best efforts of virtually every area manager at Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS, the funding has not been made available to provide permanent visitor facilities. Consequently, the ranch has yet to experience its day in the sun whereby it will realize its full operational potential.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grko/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006