|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Ranchers to Rangers An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site |

|

Chapter Three:

THE SIZE OF THE SPREAD: LANDS

When Conrad Warren opened negotiations to convey a portion of the historic ranch to the National Park Foundation in the late I 960s, he considered several alternatives. Two of those would have involved the sale of all existing ranch buildings, while another proposed relinquishing only a modest acreage encompassing the old home ranch. At that time Warren was thinking primarily in terms of a museum, little comprehending the broader needs posed by the creation of a national historic site. Because he was still actively ranching, Warren initially defined about 45 acres, including 35 on which the home ranch was situated, plus about 10 acres south of his residence for use in developing a parking lot and some sort of visitor reception facility. "We would not be interested," Warren wrote, "in breaking the ranch up in such a way that the balanced [livestock-producing] unit would be destroyed and the value of such a unit lost." [1]

When Historian Merrill Mattes had visited Grant-Kohrs Ranch a few years earlier, he acknowledged Warren's vision of creating a historic house museum with limited acreage surrounding the buildings of the old ranch headquarters. However, he offered the opinion that "a park of such limited character is more ideally suited to status as a state park." In his opinion, places having national significance should transcend the mere preservation of objects and buildings. He advanced the concept of a larger site embracing a portion of the bottom land along the Clark Fork to provide visitors with a sense of the cattle country. Mattes, in particular, recognized that the story of Grant-Kohrs Ranch involved considerably more than simply a Victorian house in the hinterland of Montana. The house was merely the result of successful livestock raising on a grand scale in the West. Acquiring additional acreage and all of the buildings, of course, would one day obligate the National Park Service to assume full responsibility for the ranch and its operation. But, Mattes was convinced that the integrity of the place justified such an approach because "one looks in vain for anything resembling a ranch in the Western United States that is in public ownership as a park open to visitors . . . ." In the Grant Kohrs Ranch was the opportunity to exhibit a working ranch and to "tell a story of the evolution of ranching operations." In his view, the National Park Service afforded the best avenue for preserving and interpreting this aspect of the nation's heritage. [2]

|

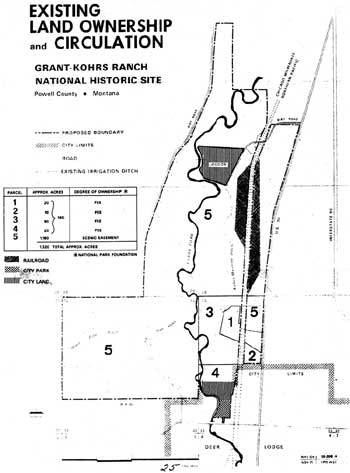

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Mattes's concept of a larger holding was reflected in the land map included with his 1968 report. The boundary he suggested at that time corresponded closely with the perimeter later defined and agreed upon by Warren and the National Park Foundation in 1970. In his formal offer, Warren identified 1,523.19 acres lying mainly between Highway 10 and the river. The price arrived at by the two parties was $250,000.00, plus survey and recording fees, and a share of the taxes. The Foundation thus purchased 130 acres in fee simple title and scenic easements on an additional 1,030 acres. [3]

As the effort to prepare authorizing legislation gained momentum, the Midwest Regional Office emphasized the need for more refined data upon which to make the proposal to Congress. In the spring of 1971, a planning team assembled at Grant-Kohrs Ranch for this purpose. Although it would be several months before a master plan could be finalized, the team rushed through a preliminary summary proposing that NPS acquire 205 acres in fee title and approximately 1,220 acres in easements. [4] The master plan team further recommended re-defining the park boundary to include additional lands west of Clark Fork, to protect a natural viewshed from the ranch as well as secure the river environment. Accordingly, a decision was made to include a large portion of Section 32 in the figures forwarded to the Washington Office as part of the legislative support package. But, Acting Regional Director Phillip R. Iversen suggested that the Warrens not be apprised of these intentions until the master plan could be completed. Then, he thought, Warren "would be in a better position to understand the rationale of the additional taking." [5]

During the legislative process the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs reported that the historic site would be limited to no more than 2,000 acres, most of which would continue to be used for agricultural purposes. Based on the NPS request, the committee advised the House of Representatives that about 208 acres would be needed in fee, along with 1,280 acres under easements. [6] The fee acreage was determined by adding the 77 (approx.) acres occupied by the Warrens to the 130 acres already owned by the Foundation. Subtracting a like amount from the Foundation's easements, the committee arrived at a figure of 953 acres of scenic lands, to which 261.43 acres were proposed to be added by the legislation. The House recommended that $350,000.00 be approved for land acquisition, of which $257,544.00 was designated as reimbursement to the Foundation for its investment and attendant administrative costs. The Senate voted to adopt these provisions in its final version of S. 2166. The approved legislation containing this ceiling for land acquisition was signed into law on August 25, 1972 and in November, the Service purchased the land from the National Park Foundation. [7]

In the months following the authorization of the area, the Service established a presence at the Site by placing a caretaker on-site and began pursuing a land acquisition program. The agency's traditional desire to reduce its inholdings was based on a long-held tenant that had originated with the founders of the NPS. For decades the Service's informal policy was to own as much of the land inside park boundaries as possible to promote the most effective protection and management of the resources. By the 1970s, though, the NPS had come to realize that it simply could not own everything and that a combination of less-than-fee strategies could be a more cost-effective means of achieving agency goals. [8]

|

|

Branding demonstration, 1982. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

The master plan, released early in 1973, clarified the lands issues. In the case of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS, the less-than-fee strategy was manifested in the Service's objective of purchasing only about 200 acres and securing easements on more than 1200 acres. The problem of visitor access, addressed in the previous chapter, initially involved the potential donation of 26 acres of Deer Lodge city-owned land at the southeast corner of the boundary. The city, while willing to promote the park by such a donation, stipulated that the parcel be developed as a picnic area and that the Park Service's extension of Rainbow Street be made available as an emergency route to the west part of the town. [9]

The Park Service approached the Warrens early on with an offer to purchase the small parcel of land containing their residence and a bit of pasture. Despite the guarantee of a life tenure, Con and Nell rejected the idea. Mrs. Warren, particularly, was opposed to this arrangement because she felt that she might be uprooted from her home if it were conveyed to the government. Unfounded as her fears may have been, she nevertheless was unwilling to take that risk. To avoid upsetting the Warrens over this matter, Vernon Hennesay, liaison for the ranch during that time, advised the Midwest Regional Office that Con should "not be approached until it is entirely appropriate." [10] By April 1973 however, Con confided to Hennesay that he favored NPS acquisition of his remaining property, but in deference to his wife's health he was not prepared to enter into any formal negotiations at that time. [11]

Con was concerned about the possible loss of the land on the west side of the river. While he understood the reasons behind Park Service's desire to assume a degree of control over that part of the ranch, he was reluctant to sell the parcel. He hoped that an easement might suffice. This was, after all, some of his best hay meadow. Hennesay attempted to clarify the Service's concerns by explaining that someone leasing those lands in the future might not have the same degree of sensitivity for the values of the Site that Con had. Another person, Hennesay reasoned, could "come in and clear off the woods on the bottom land and turn it into a haying field, which would completely change the complex of the river bottom." [12] Warren agreed to think it over. He later worked out an arrangement to sell enough of this tract to provide a corridor to protect the river bottom from the park's southern boundary northward to a point 330 feet inside Sections 28 and 29. The odd division resulted from Warren's north corral straddling the section line at that point. The east-west line of this property extended to the railroad right-of-way. The sale was concluded in February 1973. [13]

Hennesay also feared that undesirable development might occur on Tract 01-102, which had no restrictive covenant. This long, narrow parcel, containing about 37 acres, lay north of Warren's residence and was bordered on the east by the highway and on the west by the midline of Section 28. When Hennesay broached the idea to him, Warren did not understand just why development there might adversely affect the park, when, in his mind, it was the old ranch headquarters that was important. Apparently, he had not yet recognized that his modern operation would one day become an integral part of the park's interpretive story. He nevertheless agreed to sell an easement to the NPS in December 1973. [14]

The only other land transaction to occur over the next couple of years was when Con sold a tiny tract, No. 112, along the eastern border of the Site near his home in July 1975. [15] These acquisitions increased the total fee holdings in the park to 216.79 acres.

By that time, Mrs. Warren's health was deteriorating and Con's debts were mounting. "It was terrible," he recalled, "it just soaked up a herd of cattle and a couple of years of operating expenses and everything ...." [16] The proposition of selling additional portions of his ranch land to the Park Service became more appealing. Con decided to relinquish major segments of the easement lands. Despite the small purchase earlier that same year, however, the NPS was forced to decline the offer because the congressionally-imposed ceiling would not allow the purchase of the additional lands proffered. And, the addition of these 829.94 acres would be a costly proposition for the Service. Superintendent Richard Peterson set the wheels in motion for acquiring this land by preparing a legislative support package to increase the monetary ceiling for lands acquisition. But, he warned Con that it would be 1977, at the earliest, before any action could be taken. [17] It would indeed prove to be a long road.

Meantime, the Park Service continued to negotiate the land deal with Warren, a mistake that would prove costly to the heretofore cordial relationship enjoyed between the rancher and his new government neighbors. With Nell Warren confined to a rest home in Great Falls, Con and Park Service officials continued their periodic discussions relative to Tracts 115 and 117. Progress was slow, however. Valuing the house at $65,000.00 and the land at $400,000.00, Warren reminded the NPS that they were "cutting the heart out of the ranch" and leaving him with scraps of land that would be of little use to a livestock operation. [18] By the end of 1977, Con revised his offer to include only Tract 115, north of his house along the east side of the railroad, and Tract 117, the large meadow extending west of the river and all the way north to the city sewage lagoon. These he offered to sell for the same amount he had proposed earlier. The residence, apparently, was no longer under consideration. [19]

The following year NPS officials thought they had discovered a means by which the restrictions of the enabling legislation might be circumvented. A congressional action passed in June 1977 amended the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 to permit federal agencies to exceed their monetary ceilings for land acquisition by ten percent, or $1,000,000.00, whichever was greater. This windfall would have been more than enough to cover the $402,000.00 needed to purchase Warren's two tracts and, better still, the money was available to be reprogrammed from Canaveral National Seashore. All of the necessary pieces had fallen into place, or so it appeared. [20]

Just when it seemed that success was imminent, the Interior Budget Office reviewed the proposal. While they admitted that P. L. 95-42 would legally permit the ceiling to be raised, the Washington staff perceived conflicts with both the intent of the law and the park's enabling legislation. The modification of the Land and Water Conservation Act, in their opinion, was a response to escalating land values lying within national park boundaries. [21] They argued that the purpose of the law was to enable the Service to purchase such lands immediately at current prices. Had that been the only consideration, Grant-Kohrs Ranch probably would have qualified. But, the Department cautioned, the reports of the 1972 congressional hearings revealed "that they expected the Site to be made up of 208 acres acquired in fee and approximately 1,200 acres on which scenic easements would be obtained." Accordingly, Congress based the land acquisition monetary ceiling of $350,000.00 on this estimate. Had the legislators envisioned a larger taking in fee title, reasoned the Budget Office, they would have approved a larger initial appropriation for that purpose.

Since the park already owned 216 acres in fee and had easements on 1,105 acres, the pattern of ownership was almost exactly that contemplated when the legislation was passed. In disapproving the request, Interior Budget Officer Frank Wilson concluded his remarks by pointing out that, "Clearly this reprogramming proposal is not a result of rising prices, but rather a desire on the part of the Park Service to substantially change the land ownership at the Site. We believe that amendatory legislation . . . should be submitted to the Congress on this matter." [22] Interior thus "slammed down the window of opportunity," as former superintendent Vaughan related in a 1996 interview. [23]

In hindsight, it would appear that the NPS might have been too conservative in its original land estimates, probably to appease Con Warren and perhaps to avoid giving Congress the impression that the government was out to unnecessarily annex productive private lands. That short-sighted strategy may have been sound enough at the time the NPS was negotiating for the ranch, but the modest figures submitted to Congress proved to be a detriment over the long term. Despite the final legislative language limiting the Site to 2,000 acres, which the Service considered to be for the purpose of providing it some latitude in land matters, Washington Office legal analysts conceded that buying Con's 829 acres would "tip the ratio of fee to interest lands as to exceed any program anticipated by the Congress." [24]

The Department further argued that the Service had previously outlined the lands it needed to protect this historic scene, and that goal had already been accomplished. Now, it appeared that the additional purchase was "engendered more from the standpoint of the owner's willingness to sell the property than from actual park requirements." [25] That was true, at least in part. The Service was responding to Warren's offers, which stemmed from his personal financial difficulties, but at the same time NPS staff were of the opinion that if Warren sold his easement interests elsewhere, "we could have problems administering the area in the future." [26] The NPS clearly did not set out to acquire fee title to the additional lands, but when Warren's situation forced him to consider selling, the Service feared that upholding the loosely-worded easement with another owner might prove difficult, and legally expensive.

This, in fact, was the principal objection most field-level managers had to less-than-fee arrangements. While the original owner usually understood and abided by the covenants on the land, subsequent owners were often not fully informed about the restrictions until it was too late. They often felt cheated by both the seller and the Park Service. So, taking advantage of an option to purchase the Warren lands inside the boundary seemed like a prudent and legal move to everyone involved. [27]

|

|

Rancher Pete Cartwright mowing with horses,

1978. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

Although the Department had torpedoed the quick-fix plan for acquiring the Warren lands, all was not lost. Art Eck, the legislative affairs officer in the Washington Office, subsequently advised Regional Director Lynn Thompson to restructure and bolster the justification to support a change in the authorizing legislation. Eck expressed his cautious optimism that an "omnibus bill" then pending in the House of Representatives just might be a vehicle by which such an amendment could be accomplished. However, he echoed the Department's concern that two principal questions would have to be answered in the new justification: 1) how would the historic scene be better protected by fee acquisition, than by easements; and 2) what was the justification for a historic livestock operation at the Site?

The NPS-Warren relationship suffered the greatest damage as the result of the bureaucratic haggling. "Mr. Warren . . . has become much less cooperative with the National Park Service," Acting Regional Director Kenneth Ashley noted. He may not have realized then just how serious the damage was. Superintendent Tom Vaughan, who had arrived at the Site in October 1977, just in time to inherit the land issue, recorded in his 1978 annual report that Con's "reaction to our inability to complete the contemplated deal inhibited communications on historic research, the National Register nomination, and other items of mutual concern." [28] This turn of events created a chasm between the Service and Warren that would not be easily overcome. Con obviously felt that he had been betrayed by the NPS, and unfortunately Vaughan happened to be the most accessible representative of the agency.

These differences were fueled even higher in the year to come. On November 10, 1978, the president signed into law the National Parks and Recreation Act, which gave new promise to the Grant-Kohrs proposal. This act provided authority for the Service to acquire in fee title lands over which it had existing easements or other less-than-fee interests at the ranch by increasing the ceiling to $752,000.00. [29] Following Warren's offer to sell on a 90-day option, effective December 15, the Rocky Mountain Regional Office immediately forwarded a request to the Washington Office to make the purchase. They were assured that the funds would be available through reprogramming on or about June 1, 1979. Based on this new information, Regional Director Glen Bean notified Con Warren that a member of the regional lands office would be contacting him in the near future to re-open negotiations. [30] In all fairness to Warren, Bean might have cautioned the rancher that "authority" for funding did not necessarily mean that a congressional appropriation would be forthcoming right away. Nevertheless, with his hope renewed, Con proceeded to sell half of his cow herd and all of his yearlings and bulls in anticipation of the land sale. It was to prove a costly mistake to both the rancher and the NPS.

The meetings with Warren late that winter resulted in a line item request to Congress for $500,000.00 to complete the land acquisition in Fiscal Year 198 l. To everyone's surprise, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) scuttled this move until the NPS "made a thorough evaluation of alternatives to fee acquisition." With congressional hearings on land acquisition coming up that fall, Acting Director Daniel J. Tobin, Jr. advised the regional director to develop "a more comprehensive and restrictive scenic easement to achieve the protection you desire." [31] The region assured Superintendent Vaughan, in any event, that they would continue to support his land acquisition efforts in every way possible.

In January 1980, Tobin resurrected the idea of using P. L. 95-42, the amended Land and Water Conservation Act, as authority to exceed the land acquisition ceiling, at the same time suggesting that the regional office prepare revised cost estimates. One of the most valuable results of this was the preparation of a formal land acquisition plan for the park. This re-examination of the park's requirements produced several recommendations. One of these called for the removal of Tract 109, the 25.66 acres of city park lands, from the southeast corner of the boundary, since this parcel was determined to have no integrity and no potential for administrative uses. Although the land around the city sewage lagoon fell into the same category, the facility could not be easily relocated. The planners felt that there was no danger of development or other undesirable use of the property on three sides of the lagoon, but that fee interest should be purchased in Tract 117 extending south from the lagoon, because the vague language of the current easement, "for livestock ranching purposes . . . could lead to very different interpretations and to litigation . . . " [32] The plan also recommended the acquisition of Tract 115, including the modern ranch buildings, which could be used for administrative purposes, thus allowing the park to consolidate its operations. While the purchase of the Warren residence for future staff housing also was proposed, Con was assured of having lifetime use of the premises.

At the same time the Park Service was working on its plan, Con Warren took matters into his own hands by attempting to force a political solution to the problem. Congressman Stewart McKinney, acting on a request for specifics from Con's brother, Robert O. Y. Warren, wrote to the Secretary of the Interior inquiring why no action had been taken to implement the acquisition authorized by the 1978 bill. Robert Herbst, assistant secretary for Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, responded that regardless of the authority to increase the land acquisition ceiling, it had come too late in the budget cycle to include funds in fiscal year 1980. Moreover, the emphasis in the 1981 budget was on preventing threats to high priority lands. This effort, he explained, had already been crippled by a two-third's reduction in appropriated funds for this purpose. [33] The effort stalled once again.

Con Warren's frustrations with the Park Service and the agonizingly slow bureaucratic machinery reached the boiling point in June 1980. (There can be little doubt that the loss of his wife the previous November also influenced his mood.) He claimed that he had already lost $80,000 - $120,000.00, the result of selling off his cattle prematurely the year before. Once again, the process seemed to be going nowhere, and Warren thought that the recently completed land acquisition plan hinted that his property could be taken by condemnation. The situation exploded from an unexpected catalyst, and the shock was felt all the way to the nation's capitol.

Con's German Shepherd, like most ranch dogs, was protective of her territory, even when people she considered to be trespassers wore Park Service uniforms. She often confronted and sometimes nipped at staff members, who parked their vehicles alongside the lane south of the red barn. Vaughan had spoken previously with Warren about the dog, "Dru," and asked that she be confined. After yet another incident in which a ranger was attacked one evening, Vaughan decided to make a written complaint to document the situation. It so happened that this was contained in the same letter by which he provided Con a copy of the land acquisition plan. It was, at best, bad timing. [34]

In an unprecedented letter campaign, Con "wrote everybody but the president," Vaughan remembered years later. In a smoking diatribe to a shocked superintendent, Warren ordered park personnel to stay off his land, announcing that all negotiations for land were ended forthwith. Nor, would he be any further assistance to the park in any form. He had faced down the government before and, he announced, "if the Park Service resorts to condemnation proceedings with which you threaten me in your letter they will meet with the utmost resistance." "If I had known how this would end," he concluded, "I never would have started it and you and everyone connected with it would not have a job in the Deer Lodge Valley." [35]

Of course, Vaughan had not threatened Con with condemnation. The fact that this contingency was referenced in the acquisition plan was standard policy extending from the federal government's right of eminent domain. In the case of Grant-Kohrs, the Park Service reserved the right to condemn "should incompatible uses develop or be proposed . . ." on the easement lands. Warren had reviewed the drafts of the general management plan and was well aware of NPS management concerns and directions for the future. [36]

The incident relating to the dog was merely symptomatic of Warren's discontent over myriad irritations, not the least of which was his own botched cattle deal. Vaughan explained to the Rocky Mountain regional director that Warren had sold his stock on speculation, not on signed documents. He added that some incidents with "Dru" in fact had occurred west of the tracks, inside park fee lands, as well as in the access lane. There was no question as to whether or not the park staff had a legitimate right to use the lane. This was granted by the original agreement with the National Park Foundation, but it was a moot point. [37] What did matter was that Warren had taken the NPS at its word and, as one staff member put it, Con Warren was "a rancher in the grand manner; a man's word is as good as a written contract." [38]

Superintendent Vaughan had already accepted a transfer to Harpers Ferry Center in West Virginia at the time the break with Warren occurred. It was not a happy note on which to end his tenure at Grant-Kohrs Ranch, yet Vaughan was able to find satisfaction in his accomplishments toward restoring the historic buildings and improving the care of the museum collections. He later reflected that "it was time for a new set of ideas and outlooks to come in. Maybe somebody else could go in other directions that would be more productive." Upon his departure, he left a gracious letter to Con with the hope that things would improve. [39]

Con's tiff with the Park Service served a useful purpose nonetheless. Perhaps it had been designed that way. High-level attention again focused on the little historic site in Montana. Senators John Melcher and Max Baucus rallied to Warren's aid by writing to Interior Secretary Cecil D. Andrus urging him to take action in the matter. Noting that the NPS had already responded to Warren, Andrus reiterated that even though the Park and Recreation Act of 1978 had increased the monetary ceiling for land acquisition at Grant Kohrs Ranch, a legal review of the proposal had led the Department to request that the Service seek new legislation to override the original intent of Congress. Also at issue was the lack of funding, which the NPS thought would be a simple matter of reprogramming, until OMB derailed the proposal. [40] In his letter to Con Warren, Melcher placed the blame squarely on the Park Service. "There's no question they bungled this whole affair," he told Con. "They didn't have either the purchase authority or the money when they talked to you in 1978 . . . they really did fail to keep a commitment, but more through ineptness than willfulness." (The senator either was not aware of, or chose to ignore, P. L. 95-625, which unquestionably authorized the appropriation of funds for fee acquisition of lands at Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS.) He minimized the effort it would take to get an increased monetary ceiling, something he would heartily support incidentally, provided there was still a chance Warren would sell to the Park Service. [41]

In the end, legislation passed deleting the old figure for land purchases and substituting a new amount of $1,100,000.00 based on increased real estate values. Public Law 96-607 likewise raised the development ceiling from $2,075,000.00 to $7,818,000.00, in addition to authorizing the boundary change recommended in the General Management Plan. The new boundary excluded the 25.66-acre parcel of city land at the southeast corner of the Site, where the park entrance from Milwaukee Avenue had been proposed. The bill became law on December 28, 1980. [42]

It would be several more years before the Service could obtain clear title to a small parcel of city-owned land lying inside the park boundary, south of Cottonwood Creek, where it had been proposed in 1973 to construct an access off Rainbow Street. The City of Deer Lodge contested the NPS claim to this 6.074-acre tract, but it was eventually settled in the government's favor in 1987. [43]

There was, however, an inherent disadvantage connected with P. L. 96-207. This law established the boundary as depicted on a specific NPS map, No. 451-80-013. The defined perimeter actually encompassed somewhat less land than the 2,000 acres originally authorized in the 1972 legislation. No one realized that until it was too late. The 1980 law, then, effectively nullified the previous ceiling by fixing the maximum allowable acreage to 1,498.38 acres, the area included within the revised park boundary. [44]

That same day, coincidentally, a new superintendent was assigned to the area. Jimmy D. Taylor was a seasoned NPS veteran who had served as superintendent at Fort Larned National Historic Site for the previous five years. Since joining the Park Service in 1963 as a seasonal ranger, the Cheyenne, Wyoming native had been a ranger at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Capulin Mountain (now Volcano) in New Mexico, Colorado's Mesa Verde, and Capitol Reef in Utah. Taylor proved to be particularly well suited for the job that lay ahead. [45]

Taylor and Warren got along well from the outset. Certainly, the new superintendent's western origins and his experiences at numerous southwestern parks were assets at Grant-Kohrs Ranch. The new park manager recognized that Con had bruised feelings resulting from his perceived bad treatment by the Park Service. That in mind, Taylor made a concerted effort to communicate and cooperate closely with Warren, paying particular attention to listening to his concerns about the ranch and its development by the Service. It is a tribute to Superintendent Taylor's diplomatic skill that the relationship could be turned around at all. In 1996 Taylor would reflect on his effort to establish rapport and mutual respect as one of the main ingredients to the successful resolution of the lands issue. Even though Taylor admitted that Con did not always understand what the Park Service was doing, or necessarily agree with its actions, communications remained open and generally cordial. [46]

Despite the dawn of a new era of cooperation, Taylor soon had the unpleasant duty to inform Warren of yet another pitfall in the process of acquiring his lands. Since the passage of the legislation to increase the ceilings, Congress had imposed a freeze on new land acquisitions. This reversal apparently created no adverse reaction from Con, who by this time had become numb to the ways of bureaucracy. [47] The proposal to purchase the remaining Warren lands would languish for several more years.

Other land issues also arose during the 1980s. When Taylor learned that the Milwaukee Railroad was declaring bankruptcy in 1982, he contacted the company to see if an arrangement might be made whereby the NPS could purchase the 100-foot-wide right-of-way through the park lands. The railroad corridor had been a fixture in the historic scene at the ranch since the mid-1880s, when the Utah and Northern Railroad had initially purchased a right-of-way from Conrad Kohrs. Thus, the land protection plan recognized a need to preserve that element of the historic scene. [48] That same year the sent out a track crew to salvage rails, ties, and other property, beginning at the south boundary of the ranch site and proceeding through Deer Lodge. Successful negotiations, aided enormously by the revised legislative authority, resulted in the park's acquisition of the additional 27.67 acres, with rails intact, for $40,973.00. [49]

Taylor's superintendency was characterized by his initiatives to bring a better sense of order to the entire operation, including the plans for land resources. Like his predecessors, he continued to beat the drum of warning that the easements on Con Warren's land were just as loose as they had always been and that if Warren decided to sell to someone else, the NPS could find itself in a difficult situation. Taylor maintained that "it is absolutely essential that the scenic easement land west and north of the ranch remain as they presently are, open and basically undeveloped." [50] He was persistent in recommending the acquisition of the inholdings, both for that reason and so that the historic ranching operations could be expanded. Warren himself was less active in the ranching business, primarily because he had sold his herd. Subsequently, he began leasing some of the easement lands to other local ranchers. Although Con seemed disinterested in negotiating more restrictive language for the easement agreement, the new tenants began proposing non-traditional uses of this land, including the installation of irrigation systems and plowing the meadows to plant potatoes. The Park Service's worst fears were being realized. [51]

|

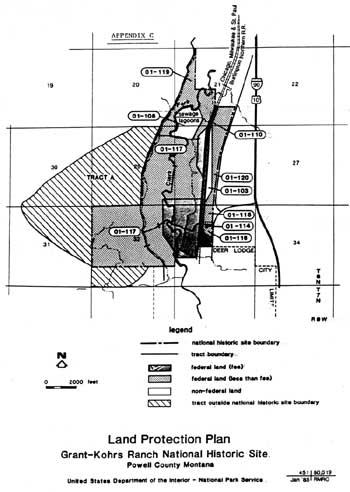

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Superintendent Taylor worked with the staff at the Rocky Mountain Regional Office to prepare a revised Land Protection Plan, which was finalized on May 21, 1985. The new title, replacing "land acquisition plan," was a reflection of provisions mandated by the Land and Water Conservation Fund requiring land management agencies to prepare comprehensive documents outlining their strategies and needs for protecting lands. This forced park management to define "management purposes and public objectives" both within and outside of park boundaries. As to Con Warren's 840-acre scenic easement, Taylor reasserted that "the easement issue remains one of, if not the most critical, issues facing the park." Taylor's challenge was to "convince those setting NPS priorities that it is important." [52] At the end of 1986 the superintendent emphasized that Warren was in his upper 70s and in poor health. "The situation can only become more complicated and almost certainly more expensive if the NPS does not make this purchase in the very near future," Taylor reported. [53] However, when he approached Warren about authorizing an appraisal, the latter declined, probably because local land values had depreciated in recent years. Now it was Con who was playing hard to get.

Nevertheless, the Park Service persisted inn its campaign to obtain the necessary funding that would permit the making of a firm offer. Warren must have sensed the time was finally right by consenting to the appraisal in 1987. The sum of $600,000.00 was therefore included in the NPS appropriation for fiscal year 1988 and in May of that year the regional lands chief, Dick Young, was able to offer a total of $485,250.00 for Tracts 115, 117, 120, and 121. This included a life estate on Con's house and associated buildings on a single acre. [54] Con, a cowboy to the end, expressed concern for the welfare of his last remaining horse, "Whiskey." One acre would not allow any pasture for the horse, so Con requested the inclusion of a life estate for the animal as well. And, to make sure, he wanted it in writing. Taylor granted the request on June 15, 1988, and the day following Con turned over the deed to the property. The NPS gained a total acreage of 1059.85, including the large Tract 117 which was vital to interpreting the open range viewshed toward the mountains. [55]

One anomaly occurred in the final purchase. The Warren property designated as Tract 117 actually extended southward beyond the park boundary to the country road and Hillcrest Cemetery. This left a small 120-acre parcel outside the Site that, if developed, would impose an adverse impact on the viewshed southwest of the ranch. The size of this tract, known as the Apple Tree Pasture, was useless to Warren for ranching purposes. Regional Lands Chief Dick Young found a solution in the Uniform Relocation Act (P. L. 91-646) by employing a provision that would authorize the NPS to purchase this land as an "uneconomic remnant." The inclusion of this parcel demands that the boundary be re-legislated. [56]

The acquisition of the Warren parcels not only achieved the long-time NPS goal of gaining full control over the ranching leases, it also granted to the government water rights associated with the lands. The West Side Ditch Company, descended from the West Deer Lodge Ditch Company formed in 1889, was an irrigation cooperative incorporated in 1917 to supply water for agricultural, domestic, and mining purposes to seven shareholders. The canal itself, carrying water northward from Clark Fork (formerly the Deer Lodge River) and Modesty Creek, closely traced the 4,600-foot contour line in Section 32. In a separate instrument, Conrad Warren sold to the National Park Service the one hundred shares of company stock he had owned for many years. [57]

Also conveyed with the remaining Warren lands were the rights to 125 miners inches of water from the Kohrs-Manning Ditch, added to the 6 miner's inches that had come with the original 130-acre historic site. [58] The irrigation system had been constructed as a joint venture by Conrad Kohrs and a Judge Manning of Deer Lodge in about 1870, as an improvement on an existing hand-dug ditch dating to 1860. This rather short canal tapped Clark Fork near the southern boundary of the Site, and extended through the park crossing Sections 33 and 28. Final water rights for the property averaged 30 gallons per day per animal unit based on reasonable carrying capacity and historic use. This additional water came from streams, primarily Peterson and Reece Anderson Creeks, in addition to springs and wells. [59]

With almost perfect timing, Jim Taylor accepted a transfer to Colorado National Monument effective July 30, 1988. He could take great pride in having resolved the major inholding issues and obtaining the water rights to the properties. The high note marking his departure was made all the sweeter by his success in rebuilding Con Warren's confidence in the National Park Service. [60]

Superintendent Eddie Lopez, who came to the ranch about a month after Taylor's departure, brought still other diverse perspectives to the issues facing management. Having been in the maintenance field, both as a workman and as a manager, Lopez was drawn to the facilities deficiencies at the site. The recent acquisition of the remaining Warren lands within the boundary afforded a fortuitous opportunity to re-examine the park's alternatives for housing visitor, administrative, maintenance, and curatorial functions. The need for permanent facilities plagued the park since its establishment. For nearly two decades, Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS had limped along with only temporary, stop-gap solutions. Administrative offices had been located in a leased storefront in downtown Deer Lodge since 1974. A "temporary" visitor contact station and rest rooms remained in an old granary and log cabin, respectively, near the parking lot at the ranch.

|

|

Superintendent Eddie L. Lopez and Con Warren,

1989. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

By 1991, most of the park plans were either inadequate or obsolete, and Lopez won support from the Rocky Mountain Regional Office to combine several of these into a single comprehensive document. This effort, headed by Michael D. Snyder, associate regional director for planning and professional services in the Denver office, recognized the lack of such basic data as a resource management plan and an approved interpretive prospectus. And, it pointed up the critical requirement for providing long-term direction to the site's facilities development.

The revised plan, released two years later, reflected the essence of the preferred development scheme presented in a 1980 GMP, in addition to the standard "no action" alternative found in all such documents. However, a variation of the 1980 plan suggested that the U. S. Forest Service share both the costs and the occupancy of a 12,000-square-foot administrative building to be located in the southeastern corner of the site, near the studs-out granary. One floor of the proposed building would lie below-grade to reduce the visual impact. Even though the construction of a new visitor center/headquarters on that tract was a viable solution to the problem, the purchase of the Warren home property opened still other possibilities. The NPS had long desired to have a public entrance near the heart of the ranch, but it was impossible so long as Con Warren continued his cattle operation. An improved entrance road past the red barn was designated for staff only, in accordance with the original 1970 use agreement between Warren and the National Park Foundation, to which the NPS also was bound. As it was, visitors commonly drove Through and out of the existing parking lot at the main entrance in the belief that they had experienced "the ranch," when in actuality they had seen only the two structures moved to the site in 1975. Indeed, the railroad grade running through the site nearly masked the historic ranch.

During 1992 a multi-disciplinary team, composed of no less than seventeen contributors from the park and regional office, resurrected the "if and when" concept of adaptively modifying Warren's 1950s red barn. This enormous structure stood a couple of hundred yards north of his residence and east of the railroads, yet within the designated administrative development zone. The plan proposed that the barn's ground floor be refurbished to house a visitor center and the second floor adaptively modified to serve as administrative offices for the park. A fifty-car parking lot would be nearby on land formerly occupied by corrals. Concurrently, a new 10,000-square-foot building is to be constructed especially to house the park's curatorial operation. This building will be sited on Tract E, in the southeast corner of the park, and is scheduled for construction in 1999. At the time of this writing, however, funding for "a modern visitor center is presently not foreseen." [61]

The ranch witnessed the end of private operations, other than those allowed by permit, when Con Warren died in March 1993. With him passed the Kohrs family legacy of cattle raising in the Deer Lodge Valley. According to Eddie Lopez, Con seemed resigned to his passing during most of his last year. "He was just very happy though that the Park Service was here," Lopez remembered in 1996. Despite his past battles with the NPS, Con obviously took satisfaction in knowing that he had placed the ranch in the stewardship of the Service for all time. The park staff displayed their respect for the old rancher by arranging to carry his coffin to the city cemetery aboard one of the ranch wagons drawn by a team of horses. A saddled horse, with boots reversed in the stirrups, followed behind. Included among the pall bearers were Superintendent Lopez and Park Ranger Lyndel Meikle, a long-time friend who had been particularly close to Con. [62]

According to the provisions of the life estate on the Warren residence, the NPS took possession of the house and other buildings on June 30, 1993. Lopez advised the executor of the estate that all personal property would have to be removed on or before that date. Fortunately, the park curatorial staff was allowed to photographically document the interior of the home with the furnishings in situ. Later that year, much of the contents were publicly auctioned, a topic detailed in another chapter. [63]

Aware that Con Warren probably did not have long to live, Lopez had initiated the preparation of a new combination general management and development concept plan. This is something the Site had needed for a long time, especially considering the changes in land status, that had not been envisioned in the 1980 plan. With the acquisition of the rest of the Warren lands, as well as numerous buildings, the park had to be prepared to assume ownership and have plans established for the use and operation of these major acquisitions.

Only a few small remnants of land remained to be dealt with inside the park boundary. Tract 103, for instance, included a right-of-way for the Western Montana Railroad consisting of 57.45 acres, with a borrow pit along the east side near the highway. Conrad Kohrs originally sold this land to the Union Pacific Railroad, which later leased it to the Burlington-Northern. In 1986 the Burlington sub-leased to the Western Montana company. The GMP recognized the historical importance of maintaining the railroad, or at least the grade and tracks, through the site. At the same time, the borrow pit, which was fenced for many decades, represented a unique sample of ungrazed Montana prairie. The acquisition and preservation of this parcel remains a management objective. [64]

Also addressed was the viewshed along the hills west of the ranch. This vast expanse has been owned by the Rock Creek Ranch for some time. Since they, too, must maintain a productive cattle operation, the owners of the Rock Creek property have shown no interest in dealing with the government, though it may be possible someday to negotiate a scenic easement with them to ensure that traditional uses of the land continue. A large white letter "P" on the far hillside continues to be a distraction for visitors. The viewshed issue was addressed in the park's 1987 Cultural Landscape Analysis and is, as yet, unresolved.

Land and water have always been a significant factor in the history of Grant-Kohrs Ranch. Grass and adequate water were essential ingredients to growing beef cattle. Just as Kohrs and Bielenberg relied on the land to support their enormous cattle empire, so did Con Warren need a smaller land base to successfully operate a modern livestock raising business. National Park Service requirements are similar, though on a much smaller scale since the ranch now exists for purposes of public education, rather than a family's livelihood. But, this has brought with it new considerations for preserving the historic scene and protecting the viewsheds across park boundaries. Future managers must continue to be mindful of the special qualities of the ranch, maintaining a careful vigilance in their stewardship of this unique place.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grko/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006