|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Ranchers to Rangers An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site |

|

Chapter Six:

CATTLE OR COOK STOVES: INTERPRETATION

When Superintendent Richard Peterson and his historian, Paul R. Gordon, arrived on the scene in August 1974, there was much to be done before the story of Grant-Kohrs Ranch could be conveyed to the public. The park was at the bottom of the proverbial barrel, with nowhere to go but up. It needed everything.

While Peterson went to work on the issue of providing a visitor entrance and parking area, Gordon attempted to bring some semblance of order to the museum collections and began conducting basic research on the Kohrs family. Gordon's upbringing on a New Mexico ranch, coupled with a master's degree in history, particularly suited him to be the park's first chief interpreter. His efforts focused initially on setting up working files that would form the groundwork for site interpretation. Conrad Warren retained ownership of the Kohrs and Bielenberg ranch records, but had agreed to allow the NPS to access them and to have them microfilmed. When Historian Edwin Bearss perused the collection back in 1970, he had proclaimed it to be "priceless in interpreting the story of ranching on the high plains to the public." [1] However, using the collection was not as easy as anticipated. According to Gordon, Warren had "a lot of stuff in his possession and he would sort of dole it out . . . in little bits." [2] Nevertheless, Warren produced a wealth of historical material over time, while Gordon and two seasonal rangers sleuthed out additional manuscript collections relating to Kohrs at the Montana Historical Society archives in Helena, as well as some deposited at the William K. Kohrs Library in Deer Lodge.

A planning directive issued late in 1974 recognized that more comprehensive historical research was necessary to "document the complete history of Grant-Kohrs National Historic Site" within regional and national contexts. Such a study would be integral to defining both the resource itself and interpretive themes for the Site. A Denver Service Center historian, John Albright, was selected to undertake this project the following year. He and Gordon worked together closely on the history component, while architect Peter Snell contributed his expertise to develop the historic structures section. Gordon's two seasonal interpreters, having no visitors to serve as yet, were dispatched to various newspaper morgues around the state to search for related material that Albright could incorporate into the report. [3] The landmark study, characterized by Superintendent Richard R. Peterson as "one of the finest studies we have ever seen," was released late in 1977. [4] Despite Albright's recommendations for more specialized research and the preparation of a comprehensive history of the ranch, his report remains as one of the principal source of historical data concerning the ranch.

The Site's first historian, like most park historians, was primarily responsible for laying the groundwork for a visitor service's program, not for practicing history. At that time, a park opening was anticipated in the summer 1975, allowing only a short time for the park staff to prepare for it. One of the first visitor needs Gordon identified was an informational brochure that would provide basic orientation to the Site. That required money, and the park had none. He quickly turned to the Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, one of many such private, non-profit organizations that exist to assist the National Park Service. Since Yellowstone National Park had been shepherding the new park from its beginnings, the association agreed to adopt Grant-Kohrs Ranch as an affiliated outlet. This benefited the new park by immediately making available a modest fund to establish a library for the Site, and $600.00 for printing brochures. [5]

What had seemed like a straightforward task, turned out as one of those instances when there were too many cooks in the kitchen. A Harpers Ferry Center contractor had, in fact, already begun drafting a text for the folder, but the effort ran aground. After delays of several months, Gordon elected instead to work with the interpretive staff at the Rocky Mountain Regional Office. It was well that the dedication of the park was delayed because the folder, which underwent many draft revisions, was not completed until 1976. Pete Peterson nevertheless was pleased with the final product, recording in his annual report that it had "proven to do the job intended; an astounding feature of any park folder." [6]

|

|

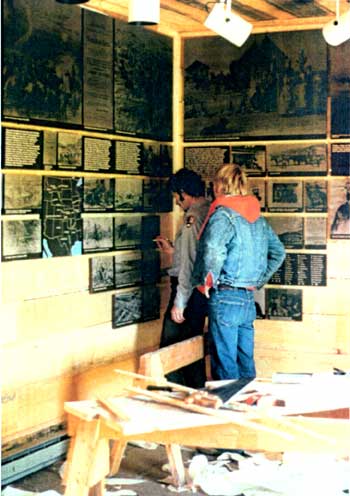

Maintenance Foreman Mike McWright and

Park Ranger Mick Holm installing exhibits, c. 1976. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

Meantime, the park was in the process of adapting two old structures from Conrad Kohrs old Upper Ranch for use as a visitor contact station and public rest rooms. By the fall of 1975 these buildings had been trucked in and placed in the southeast corner of the Site near the highway. The parking lot and walkways were also built, including a trail to the boundaries of the railroad right-of-way.

This became the sticking point, however. Peterson spent the better part of two years trying to coerce the two railroad companies involved to make good on their agreements to jointly construct pedestrian underpasses that would allow visitors to safely access the historic zone of the ranch. As the negotiations dragged on and the underpass went uncompleted until spring 1977, Peterson came under fire from the Deer Lodge Chamber of Commerce and state politicians to get the place open. This "bone of contention" had placed public relations "in a shambles, "Peterson reported. In order to appease the townspeople to a degree, Peterson and Gordon devised a policy to provide guided tours of the site, on special request, if staff members were available to do so. This plan allowed 700 persons to see the ranch during 1975, a figure that jumped to 2,000 the next year. These were impressive figures for a small park that was not officially open. [7]

Gordon and his mostly seasonal staff pursued a bare-bones operation, yet made significant strides in preparing the area for its limited initial visitation, and the greater surge that was expected after the gates were open on a regular basis. Gordon himself researched and drafted bulletins about the ranch and its principal characters to provide easily accessed, consistent information to the interpreters. His staff also arranged an "imposing display" of horse-drawn vehicles, complete with labels, in the recently re roofed thoroughbred barn (HS-15). [8] Gordon would later recall the sense of satisfaction he derived from helping the contractor to design the first exhibits, consisting primarily of photographs and text, for the visitor contact station. He also coordinated a project to produce three waysides along the trail telling of the importance of grass, as well as the winter of 1886 that forever changed the range cattle industry. [9]

These basic facilities were standard components of any new historic site, but Grant-Kohrs Ranch was to be a different sort of park. It had been proposed at a time when the interpretive concept of "living history" was rapidly gaining momentum in the museum world, and in the National Park System historic sites. As early as the 1950s, the dean of NPS interpretation, Freeman Tilden, had challenged park interpreters to animate their historic sites through the use of people, appropriate livestock, and the trappings of the era represented. The general public loved it, and more important, they could learn from it. Beyond the visual impressions created by costumed interpreters, living history could add dimensions of authentic sounds and smells and it could demonstrate how things were done. [10]

When Merrill J. Mattes first visited Grant-Kohrs Ranch in 1967 there was already a growing number of so-called living farms around the country. Mattes at that time was a senior historian at the San Francisco Service Center. In response to Conrad Warren s urgings, he and another staff member were assigned to evaluate the ranch resource and to develop a brief analysis of alternatives that might be considered for its preservation and interpretation. Mattes noted that, "The range cattle industry in its frontier aspects, has great popular appeal as attested to by the extent to which the cowboy theme has preempted the literature and entertainment fields. Paradoxically, this theme is not correspondingly well represented in the field of historic site conservation." Grant-Kohrs, Mattes noted, was one of eight rare examples of old-time cattle ranches that had been identified as qualifying for National Historic Landmark status. [11]

He concluded that there were two possible alternatives for the ranch -- the older buildings west of the tracks could be acquired and developed simply as a museum, or a larger area of the bottom lands and the Warren structures could be purchased to present "a western ranch operation, with emphasis on modern as well as historic methods." His report suggested that because Warren had "preserved several of the early historic structures as well as later structures," and the complex as a whole could tell "a story of the evolution of ranching operations." Mattes pointed out that the first alternative would present problems with trying to separate historic features from the working part of the ranch. It would be simpler and more effective, he thought, to "assume responsibility for the ranch itself, complete." In his view, it would be a mistake to staff such a ranch with government employees, rather "that a working rancher would operate as a concessionaire . . . providing that his operations would be accessible to the public . . . and subject to Service interpretation." [12]

Mattes thus inspired the basic concept that would influence the long-term development and interpretation Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site. Discussions during the legislative hearings for the Site in 1972 directly reflected his thinking for the potential of the ranch. Congressman Saylor, for instance, stated that the intention was to restore the ranch "to a condition to accept visitors into an operating cattle ranch scene." [13] A House of Representatives report "anticipated that the Grant-Kohrs Ranch will be a living memorial to the pioneers of the West, and that a concentrated effort will be made to preserve and recreate the historic ranch scene of the 1880-1900 period . . . The significance . . . is its potential contribution to public understanding . . . of the contributions of such cattle operations to life on the frontier." Although the final language of the enabling legislation was less specific, there could be no doubt that Congress meant this to be a living history ranch. As such, it would be, "the first unit of the National Park System to be devoted primarily to the role of the cattleman and cowboy in American history." [14]

When the NPS began preparing a master plan for the Site in 1972, not long before Congress was to consider legislation, the team found much of its guidance in the legislative support materials. [15] In considering how the site would be interpreted, the plan concluded that, "The primary objective of the interpretive program at the Grant-Kohrs Ranch will be to recreate the historic mood and way of life that characterized the operation of this early cattle ranch." It would be a mistake, the team calculated, ". . . to present a complex chronology of the ranch [that] . . . would only burden the visitor with facts he would soon forget . . . ." Better, they thought, to "surround the visitor with a carefully contrived montage of authentic surroundings, sketches, anecdotes, and well-selected information that will lead, not just to knowledge, but to empathy as well." To do this, "the concept of living history exhibits must be explored." The master plan strongly recommended that an interpretive prospectus, a plan outlining themes, objectives, and appropriate media, be prepared as soon as possible. However, it was evident that living history was to be an integral part of the operation; accordingly it was included among the initial management objectives. [16]

With a clear mandate to make the ranch a "living history exhibit," Peterson and Gordon took the position that a ranch was not a ranch without livestock. They soon located a pair of Belgian draft horses that were available for transfer from Lyndon B. Johnson National Historic Site in central Texas. Belgian horses had been used extensively on the ranch, as attested by Con Warren's sale of six train car loads of them at the time he mechanized his operation. It would be a long haul from Texas to Montana, but the team was there for the taking, and Grant-Kohrs Ranch was not in a position to be selective. This first pair of horses, "Dansher" and "Prancer," was delivered to the ranch by a local rancher in January 1975. [17]

That summer Ranger Ed Griggs, who had been at the ranch as caretaker for some time, was given the mission of bringing a second pair of Belgians to their new home in Montana. The trip from LBJ turned eventful when Griggs paused at a roadside rest area in west Texas to allow the horses to stretch their legs. He no sooner removed them from the trailer when one animal bolted away. Fortunately, he was able to hold the other, while he patiently waited for the miscreant to eventually return of his own accord. Farther down the road near Cortez, Colorado the government truck broke down. Griggs was stalled again, with two very large horses on his hands. He called Gordon for advice. As luck would have it, Gordon had a relative nearby, who rescued Griggs and pastured the horses at his farm until the vehicle could be repaired at nearby Mesa Verde National Park.

The pair of bronze Belgians finally arrived at Deer Lodge to great fanfare in mid August. Not long after their arrival, the Belgians stampeded in harness, hooked a wagon wheel on the corner of the stallion barn (HS-19), breaking off both the wheel and the post. "Those damned horses . . . caused more problems than they were ever worth," Gordon related in a 1996 interview. [18] A living history ranch sounded well in theory, but the practical aspects could be another matter entirely.

|

|

Ed Griggs and Mick Holm driving team of

Belgians in harness, c. 1976.< (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

Mattes's idea of placing the ranching operation in the hands of a concessionaire did not come to fruition in exactly that way, but he certainly was on the right track in recommending that a "working rancher" be employed to carry out those duties. It may have been feared that a concession-operated ranch would not have provided the Park Service with adequate control over the interpretive aspect and that trying enforce a contract would have been less cost effective than simply hiring an experienced rancher. In any event, a concessions contract for the entire ranching function was never seriously considered. A local Montana man, Pete Cartwright, was hired to fill the rancher position created in 1975. That Cartwright was a friend and contemporary of Con Warren undoubtedly benefited the park's working relationship with Warren. From that point forward, decisions affecting the ranching function would be made by the rancher in concert with the superintendent. [19]

With Cartwright on board, the interpretive staff moved to increase the types and numbers of livestock on the Site. By the close of 1977, Superintendent Tom Vaughan could report that the inventory included "chickens, shorthorns, Herefords, Belgians, and saddle stock on hand, plus cats for rats." [20] Through succeeding years, bulls were acquired to establish a small cattle breeding program. Oddly enough, ranching functions demonstrated at the Site have been of a generic 1930s nature, with no particular attempt made to pattern the operation after either the Kohrs or Warren practices. In recent years Herefords have been crossbred with shorthorns, and an occasional longhorn, to reflect something of the Kohrs and Bielenberg mixed-bred cattle. The herd has been maintained at a few dozen head, the cows and calves being sold at commercial auction in the fall of each year. [21]

Draft and saddle horses became an integral part of the program. At various times the draft teams were used to draw wagons for transporting maintenance materials wherever needed around the Site. Sometimes in winter they pulled a bob sled used for hauling hay to the cattle. On other occasions the horses were put to use for plowing the garden, harrowing meadows, planting, and demonstrating an overshot stacker in the Stuart field. No vehicles or machinery from the collections were used for demonstration purposes; these were acquired from other sources by purchase or donation. [22] Haying on the park lands was always done by leasing or contract, usually on a share basis, with the park retaining a sufficient supply to meet its needs and the rest sold. Proceeds from the living history operation, including sales of cattle, hay, and produce, were deposited in a special account and used to support the program from one year to the next. [23]

|

|

Pete Cartwright using team for hauling

materials. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS, photo by Richard Frear) |

The hard work that Peterson and Gordon devoted to the park paid off during the summer 1977 when it was possible, finally, to schedule a formal dedication ceremony. Ironically, Paul Gordon received an offer to transfer to Big Horn Canyon National Recreation Area as chief interpreter just as planning started. Peterson chided him, "Here it's time for you to really start earning your money, so you're leaving." Gordon's successor, Michele "Micki" Farmer, was selected in record time in view of the coming dedication and the park's formal opening to the public. [24]

The ceremony was slated to be held on the morning of July 16, 1977. Superintendent Peterson, fittingly, presided as master of ceremonies for a program that featured a speech by Montana Governor Thomas Judge and remarks by both Con Warren and his daughter, Patricia Nell Warren. Besides the superintendents of neighboring Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, both Vern Hennesay, first administrator for the Site, and Paul Gordon were in attendance. Some 1,000 persons showed up, overflowing the available seating set up on the front lawn of the ranch house, to witness the program. The remainder of the day was filled with a chuck wagon dinner, guided tours of the house and grounds, and living history demonstrations. [25]

Peterson saw to it that surviving members of both the Kohrs and Bielenberg families were invited to attend the festivities. After the dedication, Regional Historical Architect Rodd Wheaton became acquainted with key family members during the course of his furnishings research, discovering in the process that old family conflicts had precluded the segments from speaking to each other for many years. Relatives from both sides traveled from all over the country and, surprisingly enough, rediscovered that they had much in common. Wheaton later remarked that they all got along extremely well and apparently had forgotten all about their former differences. That in itself made the event a singular success. [26]

Wheaton himself showed up a few days prior to the dedication to put last minute touches on the interior of the ranch house. Pat Warren was there too. He recalled in a later interview that they "fluffed up" the house and rearranged some of the furniture the way Wheaton thought it ought to be, "which is the way some of it still is." They cut fresh flowers, including Augusta Kohrs's favorite, roses, and placed them throughout the house on the morning of the ceremony. It was a fabulous display in both sight and aroma. The Kohrs and Bielenberg descendants were so awed by the restoration of the house that they began to express their willingness to donate antiques still in their possession. This response was an unanticipated benefit for the park. [27]

It was appropriate that "Pete" Peterson was able to see the fulfillment of his goal of developing the park to a level that it could open to visitation. On this high-note, he left Grant-Kohrs Ranch the next month to take an assignment in Washington, D. C. Tom Vaughan, who replaced Peterson later that fall, noted that, "the opening and dedication marks a distinct and significant turning point . . . we are now open to all." [28]

Virtually overnight, the area experienced new interpretive challenges in the transition from controlled group access to an intermittent flow of visitation within regular hours. Micki Farmer recognized that the quality of some programs, especially the organization of the house tours, was not what it should be. She sought to make adjustments through trial-and-error experimentation and training. She also worked out visitor flow patterns and, to ensure uniformity of historical information, she and the interpretive staff began compiling a source book of data on historical figures, ranching operations, and Kohrs-Bielenberg family stories. Shortly before the dedication, she and Superintendent Peterson requested the regional chief of interpretation, Wes Wolfe, to conduct a visitor services workshop on-site for the staff. Wolfe considered this "a piece of cake," since several employees had come from ranching backgrounds.

Wolfe may have assumed too much because he quickly saw that the primary interpretive focus was on the elaborately furnished ranch house, rather than on the ranching industry that enabled Kohrs to own such a home. Wolfe stressed that every effort should be made to "impart to visitors an understanding of the cattle industry, before they go to the ranch." After seeing the operation, he expressed concern that, "If the Ranch House becomes a furniture tour and runs away with the show . . . we aren't living up to our legislative responsibility." In comparing the house to something "between a Turkish whore house and a maffia-styled funeral emporium," Wolfe prevailed upon the staff to remove the "gilded stanchions and the 'you ain't welcome here' velvet ropes." "Throw out the Walt Disney 'runners,' he exclaimed, "Where the crap came from, who made the crap ain't the way to give an historic house tour." The flamboyant Wolfe may have tacked subtlety, but his points were well taken. He implored the interpreters to consider the furnishings merely as visual backdrop to brief tours relying on solid anecdotal material crafted to allow visitors to "feel a home, not a house." [29]

The diminutive size and primitive nature of the visitor contact station posed restrictions on visitor orientation that were difficult to overcome, short of a new facility designed for the purpose. Although some interpreters remained wedded to show-and-tell tours at the house, Farmer and her staff began designing a variety of living history activities intended to divert attention away from the ranch house (HS-1). One of these was a campfire program featuring cowboy songs. Blacksmithing demonstrations in blacksmith shop/garage (HS-3) were popular, but they presented a dilemma. Hiring skilled artisans at the allowable general schedule grade was difficult, since they could make more money working in the private sector. Although the jobs might have been classified as wage grade positions, the park lacked the funds to pay the higher salaries. The result was that unskilled persons were sometimes hired for lower pay, with the idea that they could be trained to perform the demonstrations.

There were other problems as well. One blacksmith, while being adept at the forge, tended to produce rather ornate pieces of ironwork not usually associated with ranching. Consequently, the program became more a demonstration of that craftsman s individual skills than an enlightenment to the role of the common ranch blacksmith. In more recent years the program was been re-focused on shorter, more appropriate jobs like making hoof picks and other utilitarian items. [30]

A park "birthday celebration," initiated in 1978 became a new source of interpretive activities. Lyndel Meikle, who had come to the Site early the previous year, suggested that the park commemorate the formal opening by staging a special event on the anniversary. What began as a rather basic program that first year, quickly burgeoned into the park's most popular annual event, an event that has continued to the present day. Beyond its value for attracting a large number of visitors and attracting attention to the Site, perhaps its greater value was as a "proving ground for things that become a regular part of the interpretive program." [31] Activities such as chuck wagon cooking, talks on a wide variety of relative subjects, and demonstrations were tried at the annual celebration. Those found to be effective and well-received were sometimes been incorporated into the regular program. But, while new ideas were one thing, a small staff could do only so much to make them reality. The foundation of summer interpretive activities remained the daily ranch house tours, augmented by blacksmithing, on-going ranching activities, and self-guided walking tours of the grounds of the ranch headquarters.

|

|

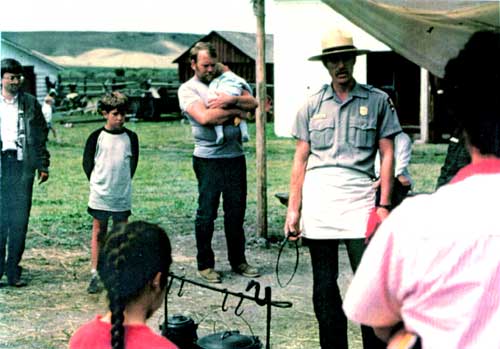

Chuck wagon demonstration, 1982. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

The late 1970s marked a period of experimentation that eventually inspired Superintendent Tom Vaughan to reflect that, "the program should be thoroughly evaluated" because the staff had "proceeded to expand [the] existing program in new directions without a clear conceptual base." He admitted that while some of these activities had "great potential," he saw a need to "make ranching activity more central to the interpretive operation . . . . The superintendent lamented that the 1979 summer program had been seriously crippled through the resignation of a permanent interpreter at the beginning of the season and the transfer of his historian, Micki Farmer, in mid-season. [32]

Vaughan turned this circumstance into a duel opportunity to make significant changes. Taking advantage of the vacant historian position, he segregated the museum function into an independent division under his direct supervision to place greater attention on the care of the collections. And, he reclassified the historian position as a chief of interpretation heading a new division of interpretation and resource management. These changes were in place by the time Cheryl Clemmensen, the new chief, arrived in the waning days of December. [33]

On a philosophical note, Vaughan challenged the premise upon which the NPS had established the "historic period" at Grant-Kohrs Ranch. He saw this as a critical assumption influencing both restoration and interpretation. Just before Christmas 1979, he penned his concerns to the regional director, stating that he thought the legislative documents, which he termed "first generation documents," ought to provide the most reliable guidance in making that critical determination. He realized, however, that they also reflected NPS policy trends, if not national trends, at that particular moment in time. In the late 1960s, for instance, when Merrill Mattes had presented his alternatives for the area, and still later when the site was authorized, the living history craze was sweeping the country. It was an era that saw the widespread proliferation of such programs throughout historical areas, and even some natural areas, of the National Park System. So popular was this technique that it came to be viewed as a universal interpretive medium, regardless of its appropriateness or effectiveness in conveying the park story. There can be no doubt that living history was popular with both the public and with politicians, but that popularity failed to recognize its limitations and its disproportionately high costs when compared to other forms of media. Period clothing, training, animals, and all of the accessories needed to activate and sustain any demonstration usually escalated the per capita costs far above other types of interpretation.

Vaughan cited an interim interpretive prospectus, prepared in 1975, as "an exceptionally good example of a second generation document that should not be canonized and enshrined in cement." In his estimation, these post-legislative documents generated by the Park Service attempted to interpret congressional intent for a particular park's purpose and resources. But, he cautioned, these interpretations were always subject to "National Park Service policy in effect at the time the document is produced." Accordingly, he thought that such documents "must be flexible enough to allow the management of the resource to be adapted to unforeseen changes in the park environment . . . as well as shifts and drifts in NPS policy." As for living history, he observed that, "Both the desirability and the economic feasibility of large-scale recreations of historic scenes and activities had undergone considerable rethinking from the time of the first generation documents . . . to the present." The real danger in all of this, as Vaughan saw it, was the "interpretation of interpretations" in NPS third-generation documents, such as funding requests and operating plans wherein the true intent of Congress might be lost, or at least distorted. To guard against this, he impressed upon his interpreters the need to review the legislative dictums, bearing them in mind during their interpretive planning. [34]

Vaughan held that, regardless of the transient influences that might have affected later NPS planning, the legislation and its supporting data should be looked to as the "true cross" of what Congress had in mind when it authorized the area. The park's first Statement for Management, a second-generation document, specified in its objectives that interpretation would "instill . . . an empathy of the life and times of the cattle rancher and cowboy [and] demonstrate ranching activities to encourage an understanding of an active frontier cattle ranch."

The literal translation of the enabling legislation was challenged in 1978 when a planning team assembled at the park to create another of those second-generation documents to which Vaughan had alluded. The resulting general management plan, headed by historian John Albright, consciously steered the interpretation of the ranch in new directions. [35] While the team acknowledged the need to focus principally on "the early frontier cattle era and the Kohrs-Bielenberg operation, . . . these aspects of the Grant-Kohrs story will be described by contrasting open-range practices with what has followed." Just as Vaughan had predicted, NPS planners re-defined the purpose of the Site by taking a considerably broader view of the story than what Congress had envisioned. On the other hand, Con Warren was an integral part of the park interpretive story, and the later-period ranch buildings could hardly be ignored. The final GMP outlined the objective as "a working ranch that illustrates the continuity and change involved in cattle ranching from 1862 to today." [36] This represented a significant expansion of the story beyond the open range frontier era personified by Grant, Kohrs, and Bielenberg, and one that profoundly affected site interpretation thereafter.

Vaughan had read the proceedings of the congressional hearings to find that the legislators clearly intended that the ranch represent "frontier life" of the "Old West" of the latter part of the nineteenth century. It may be no accident that these terms were repeated many times by the sponsors of the legislation to establish the Site. They specifically stated that Grant-Kohrs Ranch would be devoted to telling "this story" of the open range era and its contributions to the American experience. However, one of those speaking in favor of the bill qualified this by rejecting any notion that the site was "being created to memorialize any particular individual." [37] By enabling the public to "better understand the nature of ranching operations of the old cattle kingdoms," it was "anticipated that the [ranch] will be a living memorial to the pioneers of the West, and that a concentrated effort will be made to preserve and recreate the historic ranch scene of the 1880-1900 period." [38] Nevertheless, if Vaughan saw this as an example of the very divergence of purpose he feared, he did not make an issue of it.

The period of historical restoration for the ranch house (HS-1), discussed in a previous chapter, had been fixed at 1880-1900, while other buildings were to reflect their "identified periods of time," meaning their last use during active ranching operations. All of the buildings were to be "restored to a working condition," with the specific intent of using them for interpretive ranching purposes. Since it would be impossible to ignore the structures dating after the "frontier cattle era," the 1980 GMP altered the period to be interpreted so that there would an open end extending into the future. By not establishing a firm termination date, the GMP tacitly permitted interpretation to evolve indefinitely, conceivably keeping pace with the beef industry at least through the 1970s. The evidence suggests that Congress and the NPS had in mind only the days of the open range during the latter three or four decades of the nineteenth century, specifically the "frontier era." Yet, the legislators did not clearly define that point. At the time legislation was drafted, the resource had not been fully evaluated. Their concept was confined to that portion of the ranch west of the railroads, i. e., the "old" ranch. The early planning process had been disadvantaged by not having available a basic structural history, bringing to light the mixture of buildings from various eras even in the primary historic zone of the ranch.

That first GMP also addressed the constraints imposed by nearby modern development and the limitations inherent with having only a tiny fraction of the Kohrs-Bielenberg holdings within the Site. Not only were park lands a minuscule portion of the home ranch, this area was not where the family fortune was made, for the most part. At times, the two cattlemen pastured cattle on far-flung open ranges in north-central and eastern Montana, Idaho, Canada, and even in Colorado, controlling all together over one million acres. The great herds were there, not at Deer Lodge, which was a base of operations used primarily for stock-breeding. Thus, the GMP clarified that the ranch site was "not conducive to interpreting the cattle-ranching practices employed on the open range during the early frontier era," which may have provided some of the rationale behind the team's decision to expand the scope of interpretation. [39]

The implications of this debate were not lost on the park chief interpreter. By 1982, when annual interpretive reports became a requirement, Clemmensen began including brief quotations from both the congressional hearings and the enabling legislation. She stated that the purpose of the ranch was "to provide an understanding of the frontier cattle era [and] the nationally significant values thereof." Yet, the influence of the GMP was evident when she went on to define the principal objective as, "the evolution of American cattle ranching from open-range to early farm/ranch cattle raising -- as well as the development of that industry at Grant-Kohrs Ranch. This industry has continued to the present day." [40] Her inclusion of the "early farm/ranch" era recognized the 1930s buildings on the ranch.

Merrill Mattes first saw the potential for presenting the broader story of cattle ranching, exemplified in Grant-Kohrs Ranch, by demonstrating the continuum of ranching operations. However, his thoughts on the matter apparently were not considered in the support data submitted by the NPS, nor in the congressional debates, four years later. Such information might have influenced those discussions, though it became a mute point. Initially, Congress did not intend for the Park Service to buy the Warren Ranch. Yet, through its planning process and its later desire to acquire the Warren easement lands, including the ranch of the 1950s, the NPS transcended the original congressional intent expressed in 1972, i. e., acquiring 208 acres in fee and easements over the remaining 1,280 acres. [41] The Warren Ranch of the post-World War II period posed an incongruity between the enabling legislation and the central theme that both the NPS and Congress thought ought to be interpreted when the Site was authorized.

Even though the 1972 legislation did not envision the acquisition of the remainder of the Warren Ranch buildings, the 1980 and 1993 GMPs stressed that these were to be used adaptively for park administrative and operational functions. While this decision might have been construed to imply that the Warren operation of the mid-twentieth century would be de-emphasized, the 1993 GMP specified an interpretive "focus" spanning from 1860 to the 1970s. Conversely, a cultural landscape analysis contained in the same document, stated that the period of significance spanned the years 1862 - 1954. The GMP admitted that "many visitors are confused as to the story being told." [42]

During the summer of 1982, the first season in which the Interpretation & Resource Management Division actually functioned as such, the regional chief interpreter, Bill Sontag, visited the area to evaluate the visitor services program. He, too, discovered the perennial problem with more attention being focused on the ranch house tours than on the remainder of the resource. He observed that demonstrations were limited to blacksmithing and unscheduled ranching tasks around the grounds. The only scheduled programs were the house tours. He informally queried the staff to learn that while most of them were in agreement that greater attention need to be focused on the ranching operation than on the HS-1 furnishings (exactly what Wes Wolfe had warned against in 1977), some argued that the furnishings could not be ignored. Their very presence, he acknowledged, could not be disputed, but he reminded the interpreters that they "should not assume that the furnishings are interpretive features separable from the primary or overall theme of the park, but should find an appropriate blend of emphasis and carefully selected media which will place the two in proper relationship to each other." Sontag recommended that the interpreters lead each group out the back door of the house to another building, perhaps the bunk house, before terminating the tour. This, he theorized, would make a less distinct conclusion by introducing visitors to other features of the ranch. He recommended that the area have more living history activities conducted on a regular basis, rather than just on the park birthday. His recommendations resulted in some minor adjustments to the program, yet it would remain basically the same. [43]

|

|

Park Ranger Lyndel Meikle giving a ranch

house tour, 1982. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

The congressional discussions preceding the passage of the bill to authorize the area specifically highlighted the unique qualities of the main house, stating that the primary purpose of the Site would be "to describe livestock ranching as it matured and contributed to the western culture and not to memorialize the individuals directly involved." [44] The interpretive challenge was to employ Conrad and Augusta Kohrs and John Bielenberg as vehicles for telling that story without, in effect, "memorializing" them. Many visitors, especially those who had been to the Site previously, came specifically to experience the house tour. The dominance of the two-story mansion over the squat utilitarian barns and sheds on the surrounding grounds was inescapable. Its visual impact alone made it difficult to downplay and virtually impossible to ignore. One long-time staff member described the program as "resource-driven," in the respect that the house is there and people expect a tour through the Victorian wonderland. Clemmensen wrote in 1987 that many visitors "care ONLY to see the house." Even when an experiment was tried by starting tours at the bunk house, she noted that, "We still had many people who acted like the 5-10 minute introduction was a chore to sit through; they only wanted to see the inside of the house." [45] Visitors have continued to come primarily to see the ranch house and, consequently, house tours have remained standard fare in the interpretive program.

Through the years variations of program activities have been tried, with more or less success. Still, the park staff perceives a need for more orientation to the business of raising and selling cattle. "It can't be done if the staff is committed to the office, VC [visitor center], and house tours," according to Lyndel Meikle, a long-time interpreter at the Site. "It can't be done in those settings, . . . [but] it can be done with a single cow in a corral." [46]

When Superintendent Eddie Lopez arrived for duty in August 1988, he brought with him an expectation from Rocky Mountain Regional Director Lorraine Mintzmyer that living history activities would be increased at the site. This was good news to most of the interpretive staff, particularly since Lopez was not wedded to the idea of providing hourly guided tours of the house. A reduction in the frequency, if not the length, of tours would free the staff to undertake other activities.

This was easier said than done. Since Grant-Kohrs Ranch had not previously immersed itself completely in the living history concept, limiting such programs mainly to special events, the staff lacked the depth of experience necessary to conduct a more intensive program. On one earlier occasion, for instance, the staff came to loggerheads over the appropriateness and authenticity of the replica period clothing to be worn at the annual birthday event. When no one could agree, a decision was made that all interpreters, except the rancher and the blacksmith, would wear NPS uniform. When Lopez arrived, he saw an opportunity to enhance the program in this regard. However, Service guidelines mandated certain standards for the conduct of living history, so Clemmensen prudently decided that "it would require more time for research and more money for costumes than we could afford." [47] By 1990 there was still no consensus among the interpreters as to what degree the living history standards should be followed. Some were of the opinion that "modern clothes that looked 'old-timey' and appropriate" for the job assigned were good enough. Others considered this unprofessional and misleading for visitors because the interpreters were neither authentically costumed nor were they appearing as uniformed rangers. In short, they represented nothing more than quasi-modern ranch folk. [48]

These philosophical disagreements were symptomatic of more serious conflicts among the interpretive staff. To relieve this situation and provide more attention to resource matters, Lopez temporarily reorganized his staff by separating the interpretive and resource functions. This had been recommended in an operations evaluation conducted by the Rocky Mountain Regional Office in August 1990. In the resulting trial situation, Clemmensen's position was re-designated as the chief, resources management, and Neysa Dickey, formerly a supervisory interpreter, was named to head the interpretive division. This arrangement worked rather well and was later formalized so that the resources chief became responsible directly to the superintendent for overseeing natural resources management issues at the Site. This also proved to be an opportune time to transfer the rancher position to the Maintenance Division. Pete Cartwright retired late in 1990, to be replaced by Gary Joe Launderville. In consideration of the increased demands imposed by a larger land base and the purchase of the remainder of the Warren Ranch, Lopez determined that the rancher and the maintenance staff should be required to work in closer concert for mutual support. [49]

|

|

Park Ranger Bill Stalker demonstrating

cowboy cooking. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

The reorganization did not fully resolve the questions about the degree to which authenticity should be pursued in the living history program. But, an unforeseen influence from outside the park had a significant impact. By 1991 the Rocky Mountain Region had a new chief interpreter, Ron Thoman, who was not an advocate of living history. Building on a previous operations evaluation team recommendation, Thoman strongly urged Dickey to abandon living history in favor of returning to more basic interpretation, "challenging . . . visitors to use their own imaginations rather than relying on the 'gimmicks' of period clothing which can be expensive, misleading, and just plain inaccurate." Dickey concurred that, "The decision should be based on cost and effectiveness . . . not . . . on popularity with the staff or visitors." [50] That summer Dickey reduced living history activities in favor of introducing abbreviated "peek tours" of HS-1, lasting about fifteen minutes. This helped to satisfy the public's desire to see the interior; at the same time allowing the staff to conduct half-hour guided walks around the grounds of the old headquarters ranch. The success of this arrangement was limited, as the chief interpreter noted in her annual report. "The time constraints jammed up the interpreters and contributed to burnout. Since the tours were limited to 12 people, while the AV [audio-visual] programs had no such limit, they often ran out of seating. Also, if visitors went on the house tour first, they received the 'orientation' slide program afterwards. Some elected not to see it at all [departing after the house tour]... thereby negating the advantage." [51]

Perhaps the most significant impediment to making major changes to interpretation has been the park's forced reliance on the improvised visitor contact station that has been in place since 1975. This small structure has been "a serious problem and a source of frustration for the staff' for most of the park's active life. [52] In hindsight, one might question whether the park would have been better off had the granary never been installed. Grant-Kohrs Ranch, like many other park units where basic visitor needs have been served with temporary facilities, has seen its funding requests for permanent facilities defeated. Compounding the situation, perhaps, the park staff rehabilitated and improved the old granary contact station in 1983. [53]

|

|

Parking lot and visitor contact facilities. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

The fact remains that visitors at Grant-Kohrs Ranch have been deprived of a proper familiarization to both the story and the site. If the space inadequacies of the present contact station were not enough, the building itself has been something of a deterrent to visitation. Many visitors who come to the Site mistake the rustic contact station and the adjacent log cabin rest room for the historic ranch. Too, the railroad grades block the visitor's view. Unimpressed, they have departed without ever leaving their cars, thereby missing the real ranch just beyond. The regional chief of interpretation pointed this out as long ago as 1982, as has virtually every superintendent and park chief interpreter since that time. [54]

The studs-out granary, never intended to serve the long-term needs of the park, was so under-sized from the outset, hardly large enough to accommodate more than ten persons at a time, that adding an audio-visual program was out of the question. Yet, the need for a general orientation program was identified long ago. The 1980 GMP, for instance, stated that the open range cattle era, as well as the national cattle ranching industry, were to be interpreted through audio visual and exhibit media. Those, in fact, were the only effective means by which on-site visitors could be quickly introduced to the contextual history of any park theme. In its continuing struggle to meet this critical need, the park interpretive staff initiated a home-grown slide presentation in 1982, a program that was continued for several more seasons until an improved version was adopted. "Cattlemen and Cowboys," a program acquired from the National Cattlemen's Association in 1991 served as historical orientation until a fifteen-minute video was contracted and produced the next year. Until 1992 the slide programs were conducted in the thoroughbred barn (HS-15), at which time the garage/blacksmith shop (HS-3) was converted to a makeshift auditorium by the park maintenance staff. [55]

Still, the program has been handicapped by being almost totally reliant on personal services, one of the least effective methods of dealing with the historical contexts. Deprived of professionally produced exhibits and audio-visuals, visitors fail to comprehend the significance of western cattle ranching in the United States and the development of that industry, as exemplified at Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS. Visitors who gain little or no appreciation of the significance of the Site, defeat the intent of Congress in setting aside the ranch. The solution, as expressed in the 1993 General Management Plan, is to adaptively restore the red barn (HS-64) as a visitor center. "The addition of a new visitor center and state of the art facilities," stated a 1990 operations evaluation, "would lead to more efficient and effective interpretation, higher staff morale, . . . and -- likely -- significantly higher annual visitation." [56]

The area has been plagued with meager visitation throughout its short history. Given that the Site lies along Interstate 90, directly between Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, it was not unreasonable to expect moderately high visitation. However, they failed to consider was that most people do not travel to both of these large parks on a single trip. Some in the community anticipated that great numbers of visitors would pour into the ranch, and into Deer Lodge businesses coincidentally, but these wildly speculative predictions, some as high as 240,000 per year, failed to materialize. [57]

In 1978 Lyndel Meikle suggested that the park develop a special event to garner regional attention and increase visitation. The event, which she later described as "pretty much homemade at first," was scheduled in July to commemorate the establishment of the park. Initially dubbed "The Birthday," the name has given way more recently to "Western Heritage Days" as a more descriptive title, suggested by Con Warren. That first celebration attracted only about 400 people, but it was deemed a success nonetheless. Each year has witnessed the repetition of certain programs that have enjoyed popularity, while some new activities accompany what has become an annual event. By 1983 visitation increased to 1,000 and the following year it was made a two-day event. Some 2,000 visitors attended the 1995 program, drawing more people in those two days than during the entire three-month winter season. [58]

Visitation, which has consistently averaged only about 25,000 per annum, has at once been an advantage and disadvantage to Grant-Kohrs Ranch. Modest visitor use has probably worked against the various managers' best efforts to obtain funding for a new visitor center. Low visitation equates to a low priority need, some would say. Conversely, the temporary contact station could not have accommodated a higher volume of traffic had visitation been greater. To some degree, perhaps, the intermittent flow of small numbers of people through the area has dictated the types of programs that might be feasible. This also reduced the level of human impacts on cultural resources. Small groups have lended well to the house tours, to roving contacts, and to fixed stations such as the chuck wagon and blacksmith shop where the opportunity for informal discussion is an advantage.

Aside from the success of Western Heritage Days, Chief Interpreter Cheryl Clemmensen reported in 1982 that, "The Site is still not well known within the state of Montana." [59] The next year, however, Montana sponsored a one-time celebration to commemorate the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad across the state. Since Grant-Kohrs Ranch lay only fifteen miles from the site of the historic juncture, and the site included a section of usable track, Superintendent Jim Taylor agreed to co-host what became known as, "The Last Spike Centennial." It was scheduled for August 24-28, 1983.

It turned out to be a gala event, complete with a steam locomotive and tender car trucked all the way from California and placed on the rails at Grant-Kohrs. The program of speakers and music was conducted in front of the ranch house (HS-1). The site's public image was enhanced by the presence of additional NPS personnel from other parks and special living history presentations. Nearly 8,000 people attended the centennial celebration, yet Taylor was disappointed to find that it had no lasting effect on visitation at the ranch. [60]

|

|

Last Spike Centennial celebration, 1983. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

In 1992 the park interpretive staff began a cooperative project with the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks to provide the public an opportunity to learn about natural history aspect of Grant-Kohrs Ranch. This resulted in a successful application to the National Park Foundation for a $15,000.00 grant. The park resource management staff collaborated with the Youth Conservation Corps, U. S. Forest Service, as well as the Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks people to develop what became known as the "Cottonwood Nature Trail," which was completed the next year. The interpreters prepared a brochure for use on the self-guiding tour and by 1994 the new interpretive feature was in full operation. [61]

The stated interpretive objective for the area remained virtually the same until 1993, when a new General Management Plan took a somewhat different approach. The GMP's stated themes suggested a holistic approach presenting "the evolving American cattle industry," recognizing the inherent diversity of the historic resources. For many years, the chief interpreter repeated her plea for a new interpretive prospectus, stressing that "the plan is obsolete and rarely referred to by our staff" She considered a prospectus as "critical to the interpretive operations at Grant-Kohrs ranch." [62] Despite an attempt to develop a new Interpretive Prospectus in 1991, the effort floundered and was not revived, although revised interpretive themes did appear in the 1993 General Management Plan. Scott Eckberg, the presiding chief of interpretation since 1995, was of the opinion in 1996 that an interpretive Prospectus would serve no particular purpose, in light of the GMP, since that document addressed the questions of needed interpretive facilities and non-personal services media. Meantime, he, like some of his predecessors, remained distressed that the primary focus of interpretation has continued on the buildings, especially the ranch house (HS-1), rather than "on the greater story." The program, in his opinion, was still a pawn of the resource, but that it would be largely corrected whenever a formal visitor center is developed in the red barn (HS-64). Much of the story still will be told out on the ranch grounds, however. He and others on the staff felt that the interpreters need to be more familiar with animals, especially cattle, and not so reliant on the familiar and relatively easy house tour. "The tools are all here," Eckberg acknowledged, "it's the knowledge and ability that we need to cultivate among our own staff." That is the challenge.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grko/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006