|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Ranchers to Rangers An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site |

|

Chapter Seven:

REAL RANCH OR NOT: NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT

During recent decades, the National Park Service has arrived at a better appreciation for the interrelationships of cultural and natural resources in field units categorized as "historical." At the time when Grant-Kohrs Ranch was proposed as a unit of the Park System, the environmental movement was under a full head of steam and so it followed that concern for the natural setting of the ranch would be a basic consideration in planning the new site. The bottomlands and the vista to the west were deemed important to preserving the natural scenic integrity of the site. [1] Few would argue that the NPS saw the relatively undeveloped lands adjacent to the ranch as integral to the historic scene. "But not only as scenic surrounding," the first master plan cautioned. "While maintaining the pastoral scene, we cannot ignore considerations of the long-term health of the land and the purity of the river." [2]

Not long after the Service acquired the first small land area from the National Park Foundation, there was concern about the small acreage encompassed within the boundary. The master plan team had recommended that the Site boundary be extended across the brushy bottom lands so that the NPS would control both sides of the river. In those early days of the park's existence, Vernon E. Hennesay, the designated coordinator for the area, visited the ranch frequently from his home base in Yellowstone National Park. In February 1973 he noted that the tentative boundary included only about half the width of the Clark Fork River. It seemed obvious to Hennesay that it would be all but impossible to manage wildlife habitat on one bank without controlling the other. Furthermore, there was a concern that Conrad Warren might ". . . allow someone, in the future, to come in and clear off the woods on the bottom land and turn it into a haying field." According to the loosely-defined restrictions of the easements over the meadows west of the river, such an action would not necessarily have been incompatible under the broad definition of cattle ranching. Subsequently, the additional acreage was acquired in the initial purchase, demonstrating in this instance the perception of a higher need to preserve natural elements of the landscape than to promote the concept of a working ranch. [3]

For several years after the authorization of the Site and the arrival of the first personnel, little attention was devoted to the management of the park's natural resources. This is not surprising, given the area's historical classification and the acute needs for structures preservation and for providing visitor access to the area. A preliminary and very practical action in 1975-76 involved draining the water from the lower yard simply to allow use of that area.

Not until 1978 did anything noteworthy occur, and even then it was nature itself that prompted a management response. In the course of his work, NPS rancher Lewis "Pete" Cartwright observed significant erosion along one bank of the Clark Fork River within the Site. Having no expertise in such matters among the staff, historian Michele Farmer solicited help from the local office of the Soil Conservation Service. Their representative evaluated the situation, concluding that if some abatement action were not taken, it might well result in "erosive consumption of adjoining hay land or may even change channels claiming more new land and/or bypassing an existing bridge." [4] Superintendent Tom Vaughan followed up by alerting the regional office to the problem, requesting emergency funding to stabilize the crumbling bank. Regardless of NPS designs for the area, he noted philosophically, the river "upsets the plans of man" and was about to leave it with a bridge leading to an island. [5] After a delay of over three months, Acting Regional Director Glen Bean responded to Vaughan, informing him that no funds were available for the project; his only alternative was to submit a request through the usual channels.

Over time, the 1980 General Management Plan became outdated in several aspects because it failed to recognize broader resource trends and needs as the park evolved. The environmental movement of the late 1960s and '70s had given rise to a greater emphasis on the interrelationships of nature. The new philosophy rejected the traditional NPS focus on preserving only its defined "islands," ignoring what happened in the larger world. Eventually, the Park Service embraced the view that what occurred beyond park boundaries often affected resources inside the parks as well. This included the value of the total landscape, and, more particularly, the natural surroundings of historic sites. Concerned about the viewshed and potential development outside the park, Superintendent Jim Taylor justified a land protection plan in 1985 to thoroughly address NPS concerns and alternatives.

During the early 1980s, the NPS became responsible for policing itself for cultural resources compliance through a memorandum of agreement with the Advisory Board on Historic Preservation. Along with this, the Service developed specific guidelines for managing both cultural and natural resources. Thus, much of the responsibility of complying with the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act and the National Environmental Policy Act was delegated to the park mangers. This imposed a heavier workload on park staffs, who became responsible for initial determinations of effect and for preparing the required compliance documents for higher-level review. The increasing sophistication of these demands eventually contributed to a staff reorganization at Grant-Kohrs Ranch, to be discussed later in this chapter.

The erosion incident served as the impetus for the park to consider its need for baseline natural resources data. Up to that point, hardly anything had been compiled in that regard. During 1979 the Superintendent Vaughan submitted several study proposals to the University of Wyoming cooperative park studies unit. It took the bureaucratic machinery over a year to process the request, but the study finally claimed a priority in 1981. Unfortunately, no one responded with a proposal to conduct the research and the project languished for several more months. In the fall, three researchers responded, but by that time the funding had evaporated.

Superintendent Jim Taylor successfully revived this effort in 1982 when he noticed the presence of noxious weeds in the park. However, funding did not become available until August, by which time it was too late in the year to begin the field work. The project finally got off the ground the next year and carried over into 1984. The research was accomplished by scientists from the University of Montana. As a result of this comprehensive survey, the park gained floral and faunal species lists, maps delineating geographical distributions of various plants, a herbarium collection of 200 specimens for staff reference, and a collection of slides. [6]

Although rare and endangered species were identified as part of this work, more significant was the confirmation that park lands indeed were infested with noxious knapweed and leafy spurge. Both of these aggressive species are the bane of ranchers. Knapweed is especially prolific, thriving in disturbed ground, such as along roads, irrigation ditches, and the railroads, and then dominating these areas by sapping the available water and choking out competitor plants. All too often in ranching country, it meant that valuable grass is replaced by a plant that is of no benefit to stockgrowers. The areas blighted by noxious weeds accordingly reduce the potential carrying capacity of pasture lands. Real ranch or not, Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS had to do something about the problem, if for no other reason that to be a good neighbor to adjacent ranchers who depended on cattle raising for their livelihood. Even though the Site did not depend on good grass to the degree that commercial ranchers did, the intrusive species would prevent the park from producing its noted weed-free hay.

A two-pronged attack involving biological means and mechanical removal was launched on the weeds in 1985. While the common method for combating these pests outside the park was chemical spraying, the NPS chose to implement an integrated pest management plan. This approach relied on the use of natural predators -- in the case of knapweed this meant the gall fly. Larva were placed along railroad right-of-way fences, whereupon the newborn flies would begin feeding on the knapweed. It was decided that chemicals would not be applied, at least until the insects were given a fair trial. [7]

Two years later the park obtained a second grant through the University of Wyoming, this time for a project to map the areas infested with noxious weeds for monitoring purposes. Several members of the staff attended training on the subject of noxious weeds so that the eradication program might become more effective. [8]

Despite a five-year agreement with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service in Bozeman to conduct further biological control studies at the ranch, the program faltered. Several new species of insects were tried experimentally, but only two produced the desired results. All of the experiments utilized insects confined in cages. Neighboring ranchers began to lodge complaints against the NPS for not adequately controlling its knapweed and leafy spurge. Rather than risk a major public relations battle, which the NPS stood to lose, the park began chemical spraying with 2-4D on a limited basis in major public access areas. [9] This practice was later expanded to include the use of Todon on fiat, dry pasture bearing native species of grass. More recently, insects have been used in areas of the site that cannot be sprayed because of potential danger to water or other vegetation.

The natural resources research initiative of the early 1980s revealed a more insidious threat to park resources -- toxic waste pollution. Superintendent Tom Vaughan was alerted to the potential for harmful emissions when it was proposed that a previously inactive phosphate plant at Garrison, eight miles north of the Site, be re opened. The facility had been in flagrant violation of state air quality laws and eventually went bankrupt. The park, however, had no baseline data by which it could monitor the effects of the plant's operation, should it be opened again. Vaughan initiated requests to fund a research program in the event the plant were re-activated.

With the prospect of a significant threat at their doorstep downstream, the park staff questioned a potentially greater threat from mining activity upstream. Park Ranger Paul Kirkland installed a number of test plots along the west bank of Clark Fork as an introductory measure until formal scientific research could be contracted. The soil in the so-called "slickens," areas devoid of vegetation, was found to be dead for all practical purposes. Although the phosphate plant at Garrison failed to be revived, Kirkland's tests indicated a more serious danger than that posed by the potential for airborne contaminants from that source, or the impacts from the Anaconda Smelter at the south end of the valley. [10]

In the early years of the twentieth century both Butte and Anaconda were the scenes of extensive copper mining activity. Silver Bow Creek drained the watershed in the vicinity of Butte, while Warm Springs Creek flowed past the Anaconda smelter the ranch, the two joining near Warm Springs, Montana to form the Clark Fork River. At flood stage, this stream carried heavy metals waste from the mines in the form of tailings that were deposited along the streams. [11] Arrangements were made for Peter Rice and Gary Ray, from the University of Montana, to analyze park resources. Their Floral and Faunal Survey and Toxic Metal Contamination Study (May 1984) presented irrefutable evidence that the river floodplain within the Site contained high concentrations of cropper, arsenic, and cadmium. Abnormally high levels of these pollutants were discovered in broth soils and vegetation. In 1984 two areas, Silver Bow Creek (including Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) and Anaconda Smelter, were designated for cleanup as Superfund sites. [12]

The next summer Superintendent Jim Taylor assisted the Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Department to conduct a survey to determine the effects of these heavy metals on fish in the Clark Fork. Fish were netted above and below the ranch in order to weigh and measure them. Fin clippings identified the fish tested. Above the park, where lime was added to neutralize the pollutants, the sample showed nearly 500 fish to the mile. Below the ranch, in untreated waters, a mere 31 survived. [13]

Following the Superfund designation, meetings were held in the area to afford interested parties an opportunity to discuss the issues and to tour affected sites. These meetings, which were attended by park staff, also became strategy sessions to determine just what data were needed and how studies might be accomplished. By 1985 several research projects were underway to study the effects of headwater pollution caused by the Butte mining operations. Soil samples, which were taken in every mile of river from Butte to Missoula, showed the hazard was far greater than anyone had previously imagined. As a result of these surveys, the entire 140-mile stretch of river was included in the largest Superfund cleanup area in the nation. [14]

As the Superfund issue gained momentum, meetings of Interior Department agencies were called by the Solicitor's Office during 1990 in an effort to learn whether or not managers were aware of the extent of pollution on the lands within their respective jurisdictions. The Solicitor directed each agency to develop assessments of injury; Grant-Kohrs Ranch was to have its two-miles of the Clark Fork surveyed by summer 1991. [15]

|

|

Superintendent Anthony J. Schetzsle. (Courtesy of Deer Lodge Silver State Post) |

As the Superfund became the preeminent resource issue in the park, it impacted other aspects of the operation. In 1993 the staff identified several actions that were needed to adapt certain activities to existing conditions. Monitoring the quality of the river was important, since it was a primary source of water for the cattle and other livestock on the Site. While it was evident that a grazing plan was needed for the entire park in order to better manage the pastures, Superintendent Jim Taylor followed the recommendations of the Rice-Ray report by fencing the cattle from grazing in the riparian zone until the pollution problem could be mitigated. [16] Short of a major cleanup, little else could be done, except to continue to support the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in its efforts and to cooperate in research activities. In recent years, Superintendent Tony Schetzsle made the ranch available as an unequalled research site to gather data for heavy metals toxicity. Much of the information generated at Grant-Kohrs Ranch had application to other Interior agencies with lands in the Superfund area and would prove valuable for assessing damage and necessary corrective measures.

Grant-Kohrs Ranch is unique as the only National Park Service unit to be included on the National Priority List for Superfund cleanup. The EPA was designated as the lead agency for remedial cleanup, however Superintendent Schetzsle noted that, "if they are resistent to the National Park Service taking certain remedial actions that are consistent with the final remedial plan, then it is our position that EPA must then assume our congressional mandate, acknowledging that National Park System lands are special." [17]

The Atlantic-Richfield Company (ARCO) purchased the Anaconda Cropper Company a few years prior to the enactment of the Superfund law, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, and the Compensation and Liability Act. Subsequently, suits were filed in which ARCO accepted the responsibility for the cleanup, but did not fully realize the complexities of the rehabilitation process. But, according to the law, as Schetzsle synthesized it, "if you own it, whether you did it or not, the problem is yours." [18] Some remedial work is already underway at the time of this writing on the Silver Bow Creek, Colorado Tailings, and Warm Springs Ponds, but the process of eventually settling the issue and reclaiming the Clark Fork Basin promises to be a lengthy one that will continue to challenge NPS management at Grant-Kohrs for at least seventy-five years to come.

Several years after the Site was established, it became obvious that the increased attention focused on natural resources issues would require someone on the park staff to serve as a principal contact and to coordinate the various activities. A 1990 operations evaluation reinforced this need when it noted that the park was no longer a "new" area and ought to devote more attention to aspects of resource management beyond the cultural. Acting on this recommendation, Superintendent Eddie Lopez designated Cheryl Clemmensen, formerly the chief ranger, to head a separate natural resources management division. The supervisory ranger previously serving as the lead interpreter was realigned to function as the chief of interpretation. [19]

With the creation of a natural resources division, Grant-Kohrs Ranch ". . . had made the transition in terms of establishing the direction of the program," Superintendent Tony Schetzsle recalled in a 1996 interview. "It now [1994] became time to bring in skills and expertise to take that forward . . . "and to decide ". . . who was going to do the work." [20] Schetzsle originally planned to install a supervisory historical architect to oversee the combined resource operation, but later decided that he could streamline the organization by placing the two functions directly under the superintendent, without a division chief to serve as intermediary. This would reduce the a layer of supervision in concert with a Servicewide reorganization plan being affected at the time.

This segregation of responsibilities was to bode well for the park. Within a few months after his arrival at the ranch in 1994, Schetzsle and Clemmensen took advantage of a special natural resources professionalization funding initiative to improve the park's capabilities in this field. The funding of this proposal enabled the park to create three new positions -- a computer assistant, an ecologist-biologist, and a resource management specialist -- to elevate the program to a new level of sophistication. A special resources laboratory also was established at park headquarters. [21] Ironically, Cheryl Clemmensen, holding a master's degree in anthropology, lacked the appropriate academic credentials necessary to qualify for any of the newly-established jobs that she had been so instrumental in designing. She therefore elected to return to interpretive duties.

Earlier, in 1992, Clemmensen had laid groundwork for programs founded on space-age technology, the Geographical Information System (GIS) and the Global Positioning System (GPS). The former was a computer software program designed especially for land management functions. While it had numerous applications in park environments, the agricultural industry has adopted it as well. GIS, relying upon a layered spatial data base, could combine data from various sources, including maps, tabular data, and remote sensing, such as aerial and infrared photography. The GPS incorporated satellites and hand-held computers to enable precise location and recordation of almost anything, anywhere on the earth's surface.

Both of these technologies held great importance for resources management at Grant-Kohrs Ranch. In fact, the site was designated as a demonstration park for GIS applications. Cultural resources, such as archeological sites and character defining features of the cultural landscape, such as fences, headgates, irrigation ditches and other structures, could be mapped with great accuracy. Areas infested with noxious weeds could be plotted to monitor them for increases and decreases. Not only did GIS have applications in the area of fire management, its ability to show relationships between soils and vegetation made it a valuable tool in the Superfund project for detecting slickens and other affected areas. Additionally, it proved valuable for managing floodplains and riparian zones. Despite these innovations, however, these technologies have not yet been incorporated into a comprehensive monitoring system for the park's natural resources. [22]

Of constant concern at Grant-Kohrs Ranch has been the preservation of the cultural landscape. At times this has presented a dichotomy of opinion concerning two related management programs for cultural and natural resources. At the core is the necessity for maintaining the historical integrity of the ranch and its viewshed. The historic scene constitutes both the environment in which a historic place is situated, and the appearance of that feature within its environment. The degree to which that environment has been altered from the historic period must be a fundamental consideration in the overall integrity of a cultural site. The relatively pristine vista across the valley to the west was, in fact, among the reasons that Grant-Kohrs Ranch was deemed to be worthy of inclusion in the National Park System. The scenic contribution of hay meadows north and west of the ranch headquarters have been recognized for their value in virtually all of the area's general management plans dating from 1972 to the most recent one approved in 1993. The maintenance of the open landscape has been noted as a vital and integral element in helping the visitor to appreciate the cattle range of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

|

|

Winter landscape, 1983. (Courtesy of Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

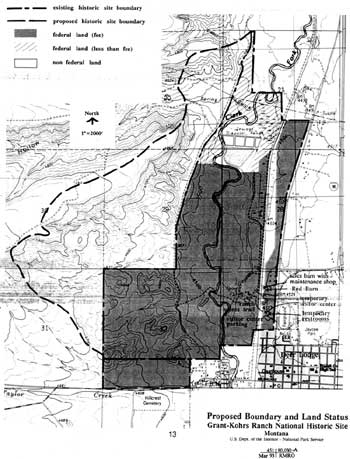

The real and potential threats to cultural landscapes emerged as a special concern of Congress as early as 1980 when the House of Representatives Sub-Committee on National Parks and Insular Affairs directed the Park Service to evaluate the boundaries of its historical areas. One park in each region was to serve as a trial sample representing one of the category types. Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS was selected as "typical of a type" in the Rocky Mountain Region. The resulting evaluation once again placed great importance on the maintenance of the viewshed, noting that the primary threat was the potential for modern development on the west slope of the valley.

The report also recommended that a restrictive easement be negotiated with the Rock Creek Ranch, owners of the westside lands beyond Conrad Warren's easement property. Within the boundary, the report cited land use on the existing scenic easement as being potentially harmful. The stipulations of the easement had trusted much to Warrens sense of what was appropriate to be "done in conformity with good husbandry practice." [23] Once he began leasing much of this ground to others, the situation became much more tenuous because the loosely-worded easement afforded the NPS practically no control over inappropriate activities. For example, there were no restrictions as to the numbers of cattle that could be grazed, nor for how long, though the NPS relied on Warren's experience and best self-interests to prescribe an optimum carrying capacity. Had he severely overgrazed the pastures or even turned the corrals into feedlots, the NPS would have been helpless to do anything about it. Fortunately, not many years passed before the remaining Warren lands, comprising the most vital viewshed, were purchased and added to the Site's authorized acreage.

Of course, the historic scene was never a constant throughout the active period of the Kohrs-Bielenberg operation. What had been virgin bottomlands in the 1860s, described by Con Kohrs as "one of the most beautiful stretches of bunch grass country imaginable," became irrigated meadows scarred with man-made ditches thirty years later. Fences were erected (and relocated periodically) as well as small bridges and flumes at various places on the property. Later, the mining pollutants took their toll on the woodlands along the water courses in the valley. Later still, Con Warren impacted the landscape with fanning, haying, grazing, and irrigation activities. The scene inherited by the NPS, then, was one that had evolved at the hands of man over a period of several decades.

|

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

A cultural landscape analysis prepared in 1987 confirmed the importance of the landscape to the central purpose of the national historic site. Land and its proper management for productive ranching were critical to the success of Kohrs and Bielenberg. There was no suggestion that any attempt be made to restore the landscape to represent any particular period of time, rather it was to be maintained to support the park's mission of providing the public with an understanding of the frontier open-range cattle era in the western United States. The lands surrounding the core area of Grant-Kohrs Ranch contributed much to telling that story, because the natural elements and the changes wrought by man demonstrate the relationship of the ranchers with the land and how ranching practices have evolved in the Deer Lodge Valley. This is seen, for instance, in Kohrs's decision to cultivate some of the native meadows and to replant them with more productive varieties of hay like oats and barley. [24]

This first landscape analysis, which did not anticipate the acquisition of Warren's easements, relied on the largely "status quo" recommendations of the 1985 land protection plan. More recently, a second study considered the enlarged area of the Site, including the additional lands acquired in 1988 and portions of the viewshed lying outside the boundary. While the study area was much the same, the 1991 analysis identified nine distinct landscape types that contributed to the "historic character of Grant-Kohrs Ranch." The report noted that the combination of these combined "to establish an overall identity to the ranch." [25] It reiterated the need for management to endeavor to negotiate some sort of covenant over the upland pastures on the west side of the valley to preclude incompatible development or other activities in that area. With reference to the Superfund issue, the analysis advised that the riparian and woodland zones along the Clark Fork should be restored to more closely represent the conditions antedating the heavy metals toxification of those areas.

Work was begun to accomplish that end beginning in 1994. A program spanning two years administered by the Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Department resulted in the planting of willow and other species along the river banks. This accomplished a two fold benefit by enhancing the historic landscape and helping to stabilize the eroding banks that had been a recurring problem since the late 1970s. Concurrently, a complete vegetation survey was conducted by the University of Montana with NPS funds. [26]

The management of natural resources at Grant-Kohrs Ranch has matured with time. Although for many years concern for the natural environment took a secondary role to the cultural aspect, they have become virtually inseparable in a cohesive management philosophy aimed at preserving the values and historical integrity of the ranch. The NPS mission to preserve the ranch as a working cattle operation has presented numerous conflicts between the way park resources might normally be managed and the methods "real" ranchers might use in contending with the same situations. Like it or not, the NPS is bound by laws, regulations, and guidelines that dictate the treatment of natural resources. Meeting these dictates, while attempting to operate a ranch in ranching country, requires a delicate balance of science, practicality, and public relations. As one employee phrased it, "Natural resources is a can of worms on a cultural site." [27]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grko/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006