|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Ranchers to Rangers An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site |

|

INTRODUCTION

In the decade following World War II an expanding and prospering American public frequented its national parks as never before. It was predicted that visitation to the National Park System would double by 1960. However, by the mid-1950s most park facilities had seen no major improvements since the days of the Civilian Conservation Corps, in the 1930s, when great amounts of money and labor had been infused into the System. In the intervening years, during which the nation's attention had been dominated by World War II and the Korean War, roads, bridges, and utilities systems had deteriorated to an alarming degree. Housing for park employees was often worse, consisting of make-shift and barely habitable cabins. [1]

Alarmed at the impacts of this massive influx of people, National Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth proposed to Congress a ten-year program aimed at rehabilitating the system. This major overhaul of the national parks, termed the Mission 66 Program, was to be accomplished in conjunction with the 1966 fiftieth anniversary of the National Park Service. Both the Eisenhower administration and Congress endorsed Wirth's ambitious plan.

In addition to the general improvement of facilities and the construction of dozens of new visitor centers, hundreds of employee houses, as well as new roads, trails, and maintenance buildings, Mission 66 also affected a dramatic expansion of the Park System. The Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, administered by the Department of the Interior, was reactivated in 1957 following a hiatus of several years. The program was intended to identify and evaluate nationally significant properties throughout the United States and, with owner consent, designate them as National Historic Landmarks. Ultimately, these were eligible for consideration for inclusion in the System. A similar program was initiated for natural history areas. Even when designated properties lacked the qualities to meet basic criteria to become official units of the System, these inventories nevertheless provided official recognition, and local attention, to thousands of sites that otherwise might have been destroyed inadvertently.

|

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

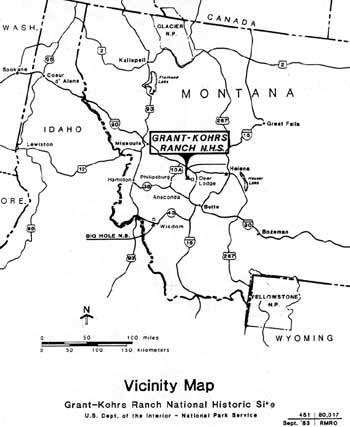

One of the properties singled out during this process was a working cattle ranch owned by Conrad Kohrs Warren at Deer Lodge, Montana. Now known as the Grant Kohrs Ranch, it was the site of one of the Montana's earliest ranches, which eventually became one of the largest cattle raising operations in the West.

The ranch that would eventually burgeon into a cattle empire had humble, if not unlikely, origins in the commerce of the Oregon Trail. "Captain" Richard Grant, a Canadian of Scottish and French ancestry, was already a twenty-seven year veteran of the Northwest fur trade when the Hudson's Bay Company assigned him to manage its affairs at Fort Hall, in what is now the state of Idaho. The company had purchased this post on the Snake River in 1837 for the purpose of extending its wilderness trading empire, as well as to bar American trade from expanding into the Pacific Northwest. By all accounts Grant was a large man, who was "pleasant for an Englishman," according to one Yankee passerby. [2] Grant assumed his new duties as factor in June, 1842,* little realizing then that his tenure there would span more than a decade.

Besides continuing a profitable business trading manufactured goods to the Indians in exchange for furs, Grant fell into a lucrative sideline. By the mid-1840s there was a significant number of emigrants passing over the trail to Oregon. Those who made it that far often were burdened with half-starved, footsore cattle and horses. Although the short-horned cattle were frequently of good English-American blood lines, having been selected to start herds in the promised lands of Oregon and California, these animals were all but useless by the time they reached Fort Hall. Grant saw this as an advantageous opportunity to relieve the emigrants of their lame cattle, and at a handsome profit for the company. An emigrant arriving at the post in 1845 observed that,

The garrison was supplied with flour, which had been procured from the settlements in Oregon, and brought here on pack horses. They sold it to the emigrants for twenty dollars per cwt. [100 lbs], taking cattle in exchange; and as many of the emigrants were nearly out of flour, and had a few lame cattle with them, a brisk trade was carried on between them and the inhabitants of the fort. In the exchange of cattle for flour, an allowance was made of from five to twelve dollars per head. They also had horses which they readily exchanged for cattle, or sold for cash... They could not be prevailed upon to receive anything in exchange for their goods or provisions, excepting cattle or money. [3]

Grant pastured the cattle from one season to the next, time enough for them to regain their weight and health. The following year he would offer west-bound emigrants in need of fresh stock one of these rehabilitated animals in exchange for two head of their worn out cattle. [4]

While Grant showed no hesitation in profiting from the Oregon Trail traffic, some passersby were of the opinion that he was "unwilling to have the country settled by the Americans." [5] Unquestionably loyal to the Hudson's Bay Company, Grant may have simply represented his employer's interests by attempting to discourage emigrants from continuing their journey to the Oregon Territory, a region whose ownership still was disputed by both Great Britain and the United States. Grant no doubt appreciated the potential threat that a great influx of American settlers may have posed to British control of the Northwest. According to other accounts, however, Grant simply informed travelers of the rugged conditions to be encountered on that route, often suggesting that they take the alternate, more easily traveled trail branching off to California. To those who insisted upon going to Oregon, Grant sometimes made an exception by offering to take wagons, for which he had little use, in trade for supplies. The truth of the matter probably lies in a combination of influences, wherein interests of both California and the Hudson Bay Company came into play. [6]

By 1851 an aging Richard Grant recognized that the fur trade was all but dead. When declining health posed a hindrance to his transfer to a more northerly post, as ordered by the Hudson's Bay Company, Grant elected to retire and take up the life of a free mountaineer. He afterward established his residence at an abandoned army cantonment near Fort Hall, from which he conducted personal trading operations with both emigrants and Indians. [7]

Grant's younger adult son from his first marriage, John Francis, was already well-established as a mountaineer and trader in his own right, having struck out independently two years earlier. His taking of a Northern Shoshone wife further enhanced his status and business opportunities among some of the native inhabitants. Based at Soda Springs, east of Fort Hall near the fork of the Hudspeth Cutoff, the Grants continued to actively trade replacement cattle to emigrant farmers, as well as to eager California-bound prospectors. They augmented lucrative summers on the trail by wintering in the mountains along the Salmon River where they traded goods with the Indians. [8]

The Grants traditionally drove their cattle north across the Continental Divide to pasture on the lush grass in the Beaverhead country, in present southwestern Montana. There, sheltered and unmolested by Indians, the stock could recuperate and fatten in a relatively mild climate. In summer part of the herds were separated and driven southward to the trail for use as trading stock to the emigrants.

Reacting to rumors of sedition among the Mormons in 1857, the United States Government ordered a strong military expedition under the command of General Albert Sidney Johnston to Utah to quell the alleged rebellion, if not to subjugate the Mormon population. Latter Day Saints leader Brigham Young immediately ordered his followers to mobilize to resist the threatening invasion. The Mormons quickly took the offensive by sending out armed parties along the trail east of Salt Lake City to destroy potential supply points, including Fort Bridger, and to execute a "scorched earth" policy aimed at denying forage to the advancing federal army.

Meantime, the Grants returned to the Beaverhead region in the fall, happy enough to distance themselves from an impending war. There Richard resided "in a good three room log house" at the mouth of Stinking Water Creek, just north of present-day Dillon, Montana. From this base, Richard Grant and a group of former Hudson's Bay employees continued trading on the emigrant road, as well as with the Indians in the region. [9]

John Grant remained for a time near his father's camp, later moving to the Deer Lodge Valley for the winter of 1857-58. When a government contractor negotiated a deal to purchase two hundred head of cattle from Grant to supply Johnston's column at Fort Bridger, Grant declined to deliver the herd for fear the Saints would retaliate against him. By this time Grant considered himself a permanent resident and businessman in the region and thus had no desire to make enemies of the Mormons, with whom he had to deal, war or not. Salt Lake City was, in fact, his principal point of supply. Despite the loss of this sale, Grant later chanced selling the troops a few dozen horses, which he drove to Fort Bridger the following spring. [10]

The elder Grant, also concerned for the safety of his property, packed his goods and trekked farther north to Hell Gate, in the vicinity of modern-day Missoula, early in 1858. There in the Flathead Indian country of the Bitterroot he continued to raise cattle successfully for another three years, until a particularly hard winter decimated his herd. His roving days came to an end when he journeyed to The Dalles in Oregon to obtain supplies over the winter of 1861-62. On the return trip in the spring, Grant suffered from over-exertion and died before reaching home. [11]

In the summer of 1858 Johnny Grant, as he was universally known, returned to the Bitterroot, where he had left his cattle on shares with John M. Jacobs during his trip to Fort Bridger. He then drove this stock back to Henry's Ford, near Fort Bridger, where he happily discovered that the other traders had disposed of their entire herds to supply the Utah Expedition. As a result, Grant's competitors were left with only the emaciated cattle they had been able to buy from passing emigrants that season, When Johnny arrived with his fresh herd that fall, he immediately began trading his fat steers, at the rate of one head for two. That winter he chanced grazing these cattle in the vicinity, rather than returning to Montana, so that by the next spring he had a sizeable herd to offer the emigrants.

Although Johnny Grant was in an advantageous trading position during the summer of 1859, he perceived that the traffic over the trail was less than it had been previously, a factor that likely prompted him to return to the Deer Lodge Valley that fall. [12] The relatively mild climate, clear mountain streams, and an endless abundance of rich grass made it a near-perfect place for raising cattle. It was a good place to settle down with his family, which by this time had grown to include three Indian wives and a number of children. His rough-hewn log cabin stood at the mouth of Little Blackfoot Creek, about twelve miles north of the present ranch. [13]

Despite the prosperity he found in the Deer Lodge Valley, Grant discovered that it was a lonely existence for a family accustomed to interacting with people during the Fort Hall days and later with their mountaineer clan on the Beaverhead. A few Indians and even fewer white men occasionally passed through, but none stayed. Bored by the solitude, Johnny decided to journey back to the Oregon-California Trail to see if he could induce some of the west-bound settlers to follow him back to Montana. His glowing descriptions of the country persuaded about a dozen families to redirect their destinies to the Deer Lodge Valley. These few formed the nucleus of a settlement christened, appropriately, "Cottonwood." Later, it would re-named Deer Lodge.

The Grants resided on the Little Blackfoot for about a year after his quest for neighbors. In 1861, still somewhat isolated from the society now offered at Cottonwood, he gave up his first home and moved near the settlement. There, on the east bank of the Deer Lodge (Clark Fork) River, he first built two small adjoining cabins, augmented in the fall of 1862 by a handsome two-story home of hewed logs. Today this substantial house remains as the centerpiece of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site.

Not long afterwards the other principal character in the Grant-Kohrs saga made his entrance on Montana's territorial scene. In 1862 Danish-born immigrant Conrad Kohrs, drawn by the news of gold strikes in Idaho Territory, traveled through the Deer Lodge Valley. By the time he arrived at Cottonwood, however, he was nearly destitute. Needing a grubstake to start mining, Kohrs was only too happy to accept the offer of employment as a butcher at the boomtown of Bannack. Con, as he was known, had gained some experience in the trade while employed in a family-owned meat packing house in Davenport, Iowa. He little knew then that he would discover his bonanza in beef, not gold, and that it would be the foundation of an empire.

Young Conrad Kohrs quickly mastered the business. The shop owner recognized his abilities and soon entrusted Kohrs with keeping the books for the shop. Hungry miners made for a thriving business and Con discovered that the surest way to make money was by supplying their needs, not working the mines.

After a run-in with Henry Plummer, territorial sheriff and head of a band of road agents, Con's employer hastily cleaned out the cash box and left town, Left with the shop, Kohrs suddenly found himself in the meat business. Before long, he was turning a modest profit, which he began reinvesting in cattle to supply his business. Kohrs soon expanded his interests by opening additional shops in neighboring gold camps. Always prudent in his business affairs, Kohrs relied foremost on his family as a source of partners to operate these shops, convincing his Bielenberg half-brothers Charles and John (twins) and Nick to join him in Montana for that purpose.

Kohrs was a inherently astute business man who soon realized that by raising his own cattle, he could control both ends of the business, thereby cutting costs significantly. His herds grew rapidly as the result of careful breeding, almost boundless grazing opportunities, and purchases of additional livestock. By 1865, he was one of the leading cattlemen in southwestern Montana Territory.

The extensive Kohrs cattle operation demanded a ranch with adequate pasture. In 1864 Con acquired a ranch on Race Track Creek, but by this time he was well-familiar with the Deer Lodge Valley and had undoubtedly noted its attributes for raising and wintering livestock. His business dealings had also brought him into contact with Johnny Grant, whose ranch was ideally situated for Kohrs's needs. Although Grant declined Con's first offer to purchase the ranch in 1865, a desire to move his children to a more hospitable environment prompted Grant to reconsider a year later. [14] Kohrs paid him $19,200 for the property, including all improvements and about 350 head of cattle then grazing on the place. Soon thereafter Grant departed for Manitoba, thus closing his era of cattle trading that had spanned two decades. Con took up residence at the ranch in September, 1866. From this base of operations, "... . in name and fact the 'home ranch,' he would supervise the varied and dynamic Kohrs and Bielenberg cattle operation and mining activities." [15]

Con Kohrs had come a long way since his inauspicious trip through the Deer Lodge Valley just four years earlier. Not only was he a leading meat purveyor in western Montana, but he was now the most prominent cattleman, owning the former Grant ranch, as well as additional land on the west side of the Deer Lodge Valley. The stage was set for a new era in both the life of Con Kohrs and the development of the Montana cattle industry.

Since his arrival in the territory a few years earlier, Con's half-brother John Bielenberg had become a close and trusted associate in the enterprise. These two energetic men made an effective team, each playing to his respective, yet mutually supportive, strengths. While Con ranged far and wide making bold but solid deals in cattle, land, and mining interests, John usually stayed close to the ranch managing the day-to-day operation. It was a comfortable partnership that would thrive for over fifty years, until Con's death in 1920.

Conrad Kohrs, at the age of thirty-two, was by this time firmly rooted in western Montana Territory. Already well-off financially and highly-regarded among his peers, Con lacked only one ingredient in gaining the full measure of respectability -- a wife. When he decided to spend Christmas 1867 with his mother and step-father in Davenport, Con may have sensed that he would return a married man. In a letter, Con's mother had played Cupid by reminding him of a childhood acquaintance, August Kruse, now a beautiful and eligible young woman of nineteen, Con found Augusta at her home in Ohio, courted her for two or three weeks, and returned with her to Iowa, where they were married in February, 1867. After honeymooning until April, when the spring thaw cleared the Missouri for steamboat travel, Con and his bride of six weeks made the long, arduous journey home to the ranch.

If Augusta had any second thoughts about what she had gotten herself into, she did not allow them to discourage her. With a typically German sense of order, she immediately took charge of the two-story house and made her imprint on it, A working cattle outfit it may have been, but the house soon became Augusta's domain, Domesticity had arrived in no uncertain terms at the Kohrs-Bielenberg Ranch, She deftly integrated herself into the society of what was now called Deer Lodge City, easily assuming the role of wife to one of Montana's most successful entrepreneurs.

By 1870 Kohrs and Bielenberg had expanded their cattle operation far beyond the home ranch. With the herds growing rapidly and grass becoming increasingly scarce in the Deer Lodge Valley, the partners looked to the open range northeast beyond the mountains. There in the country south of the Sun River the cattle could fatten on an almost boundless area of free grass, with little tending until the late summer roundup. It was at about this same time that the half-brothers began to explore wider markets for their beef. Always alert to new opportunities, Kohrs began shipping cattle to Chicago via a southerly route down through Idaho and across southern Wyoming Territory to railheads at Cheyenne and North Platte. An alternate trail from the Sun River range led southeastward through the Crow Indian Reservation to link with the Western Trail passing through eastern Wyoming to Cheyenne. In connection with this growth, Kohrs and Bielenberg also placed a large herd on the Snake River and another that was moved variously from western Nebraska, to Wyoming, and even into North Park, Colorado, depending upon where the grass was best. All of this activity marked a major turning point in the business and thus established a pattern that would be followed and further developed in the future.

Ever the wise businessman, Kohrs reasoned that by sharing the investment in herds with other partners he could maximize his capital and, correspondingly, reduce his potential losses. If all went well, he still made money, albeit not as much as he might have by owning the entire herd himself. But, the losses in one herd were usually offset by profits in another deal. Of additional benefit, were the sound relationships he formed with other cattlemen, as well as financiers in Chicago, thus enhancing his reputation and bolstering political connections that would bode well for him in later years.

Even as the cattle operation grew, Con maintained firm control over the other aspects of his meat business, The vertical diversification method he had established early-on continued to be the foundation of his success, Besides selling live cattle to more distant markets, Con continued to supply animals to his butcher shops in a half dozen western Montana mining towns, and to his own new two-story store in the town of Deer Lodge.

The prosperity that Kohrs experienced by the I 870s was reflected in several aspects of his professional and personal life, It allowed him, for instance, to purchase additional lands for the home ranch in partnership with Bielenberg. From time to time, they bought up small ranches neighboring the home ranch, as well as parcels of pasture land, which increased the grazing area for the home herd used to supply the butcher shops. With John handling much of the routine cattle operation, and with other reliable foremen managing affairs on the far-flung ranges, an unquestionably affluent Con Kohrs found more time to engage in activities not directly related to his business. The early years of the decade marked his entry into local politics with his appointment as a territorial prison commissioner. He also took time for an extended vacation to Germany with Augusta and their two daughters, something that would become a tradition every few years thereafter.

Con Kohrs clearly loved making a good deal, One of these occurred in 1883 when Con purchased 12,000 head of cattle and other ranch property for the price of $400,000.00, marking the largest such transaction in Montana up to that time. Profits aside, it seems unlikely that he was motivated by wealth for wealth's sake. What does become apparent is that he derived great pleasure from wheeling and dealing on a grand scale, He was the consummate entrepreneur.

In the early 1880s, the Kohrs-Bielenberg partnership thrived beyond all previous measures of success, It was big business. No longer was it an operation that could be managed on a daily basis by its owners. Much of the immediate supervision of the herds, as well as the drives and even some selling, had to be relinquished to trusted foremen, Both Con and half-brother John assumed oversight responsibilities, riding long distances to monitor the various herds.

In the late-1870s Kohrs and Bielenberg grazed stock on various ranges from above the Canadian border to the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory. When the completion of railroads negated the need to drive cattle along the old southern route, Con began using a trail that struck eastward from the Judith Basin to railheads located first at Miles City, and later Custer Station and Billings. The days of the long drives thus came to an end, Cattle could be shipped directly from the territory to markets as far away as Kansas City and Chicago. After the construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad across the territory in 1883, coupled with the decline of the buffalo that had competed for the available grazing range, livestock operations shifted principally to the Sun River region on the plains east of the Continental Divide.

The Deer Lodge Valley remained nonetheless important for pasturing animals intended for the Kohrs butcher shops. During the late 1870s, the home ranch had assumed an increasing importance as a breeding operation. Kohrs had long recognized the advantages to improving the quality of his cattle. This in mind, he began acquiring blooded Short Horn breeding stock from the Midwest. Most of these animals, the numbers of which multiplied significantly after 1880, were pastured and cared for at the home ranch during the winters, Kohrs and Bielenberg added registered Herefords in 1884.

A massive influx of cattle brought in from other areas by speculators in a booming market, began to compete for the ever-shrinking Montana range lands by the mid-I 880s. The enormous herds belonging to Kohrs-Bielenberg and Montana pioneer Granville Stuart, in addition to those of several foreign stock growers, rapidly depleted the grass. The quality of the northern ranges declined so that it became increasingly difficult to support such large numbers of cattle. Seeking additional range lands, Kohrs and Bielenberg leased large acreages from the Canadian government and petitioned to have more land opened for grazing within the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory. In 1886 the risk of loss was made more acute by dry conditions that failed to replenish the grass. Prairie fires took an additional toll on the ranges. Experienced stock growers recognized the precarious situation posed by the steadily escalating numbers of cattle and the fragility of an overgrazed range, yet they trusted to luck rather than change their methods.

Winter came early in 1886. And, it was uncommonly severe. Blizzards brought temperatures that plummeted to sixty degrees below zero. Even when cattle were able to dig through the crusted snow, there was no forage to be had. The grass was gone and they died by the thousands. When spring finally came, the coulees and stream courses were filled with the stiffened and rotting carcasses of what had once been the great herds. Most of the British cattle investors who had seen what they thought was an opportunity to make an easy fortune, lost all and disappeared from the range as rapidly as they had come. Many of the large ranchers and most of the small ones, unable to withstand the staggering financial losses, also went bankrupt during the months that followed. Kohrs and Bielenberg, Stuart, and some others of the most wealthy stock growers managed to hang on, despite the loss of half to two-thirds of their stock, mainly because they commanded the financial reserves to absorb such a disaster, Con's strategy of diversifying his interests among cattle, land, and mining stood him in .a reasonably stable position during the crisis, though he had to borrow heavily to regain momentum. Particularly fortuitous was the placement of the registered breeding stock at Deer Lodge, where the winter had been comparatively mild. Kohrs and Bielenberg had the genesis of a new herd, but the nature of the cattle industry would remain changed forever.

The days of the open range were numbered, and the stockmen who had survived the catastrophic losses of 1886-87 had to make changes to stay in the business. No more would large ranchers allow their herds to graze at will on vast, unfenced plains. Kohrs and his contemporaries became much more conscious and watchful of range conditions and carrying capacities. Ranchers also became serious students of cattle breeding to improve the quality of their stock, resulting in more weight per head, thus reducing the numbers necessary to generate adequate financial return.

During the 1890s Kohrs altered his approach one other important way. The home ranch previously had been considered as a permanent land base and home to the registered breeding stock. The bulk of the cattle had roamed on the enormous acreages of unclaimed government lands, The ranchers who managed to survive the crushing losses of 1886-87 were compelled to recognize, finally, that stock growing demanded better breeding, consolidation of operations, and wise land management using an increased ratio of acres per head to avoid overgrazing. Gone were the days of free land as homesteaders moved onto the plains. Accordingly, Kohrs and Bielenberg aggressively bought up tens of thousands of acres of land in the Deer Lodge area, whenever they could get it at cheap prices. These acquisitions continued through the decade of I 890s and well into the early twentieth century. By so doing, they placed their operation on a self-sustaining basis, combining pasture with meadow lands that provided hay for the winters.

Time brought other changes to the ranch. In 1894 Con, then age 59, suffered a serious injury while riding. Both years and the injury limited considerably Con's ability to actively run the ranch. The taciturn John Bielenberg, although eleven years his junior, could hardly manage the still extensive operation by himself Therefore, a younger and more vigorous manager was found in John Boardman, who had married Con's eldest daughter, Anna, in 1891. Both Con and John placed great faith in Boardman. While Boardman continued to direct the daily ranching activities until his death in 1924, Con developed strategy for the future of the operation. In this, he was unexcelled and had always been the "brains" of the business.

With the ranks of their Deer Lodge friends thinning with the passage of time, and the ranch in good hands, Con and Augusta decided there was little to hold them there. Despite their love for the ranch and the valley that had been their home for more than three decades, they decided to move to Helena on a trial basis in 1899. A few months later, Con purchased the large home they had been renting, after which they usually made only summer visits to the ranch. [16]

The rapid and irresistible development of the western U. S. after the turn of the century had its effects on the Kohrs-Bielenberg Ranch, By 1914 homesteaders moving into Montana occupied much of what formerly had been open range land used collectively by the cattlemen. With the homesteaders came fences and plows. Recognizing that the old days were gone and sensing that the time was right to begin selling out, Con, Augusta, and John Bielenberg formed the Kohrs-Bielenberg Land and Livestock Company in 1915 to incorporate most of their property holdings. That done, the aging cattle kings began to liquidate their extensive acreages the following year. Sales progressed quickly and in just three years the ranch that had taken most of a lifetime to build, was reduced to mere remnants.

By 1924 Con Kohrs, John Bielenberg, and John Boardman all were dead. That same year witnessed the last of the ranch land sold, with the exception of a reserve of about one thousand acres surrounding the buildings of the home ranch. For the next few years a succession of hired caretakers managed what was left of the ranch, but the old cattle empire, like its founders, had passed into history.

The famed ranch was all but dead when grandson Conrad Warren, son of Katherine Kohrs and Robert O. Y. Warren, began working there in 1926 as a hand on the haying crew during summer recesses from college. Following his attendance at the University of Virginia, Con Warren returned to live and work at the ranch from 1929 to 1932. Whereas the other grandchildren took no interest in ranching, young Con did. As a boy he had shadowed the old ranch men, Grandfather Kohrs and Great-Uncle John Bielenberg. He watched, he worked, and he learned. They in turn favored the boy who displayed an interest in what had been their life and livelihood for so long.

When the ranch caretaker left in the spring of 1932, Con Warren was handed the reins of the operation as its new manager. No longer would the ranch languish as the stagnant business it had become in the hands of non-family employees. Warren realized that the ranch would never again see its former glory, but in order for it to support a family, it had to be revitalized into a paying, beef-producing operation. Through the 1930s and 40s Con stocked the ranch with fine purebred Herefords and registered Belgian horses. Within twenty years, he had attained national recognition as a stockman in his own right. Had Con and Nell Warren's children elected to devote their lives to ranching, the family tradition might have continued, and there would not have been a Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site. Con Warren was a proud man, both of his ancestry and of what his grandfather had accomplished during his lifetime. Con thought that was worth preserving, but how?

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grko/adhi/intro.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006