|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Ranchers to Rangers An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site |

|

Chapter One:

GOING INTO THE CATTLE BUSINESS: ACQUISITION

When Conrad Kohrs Warren assumed the management of his grandfather's ranch in 1932, he had no thought that it might one day become a unit of the National Park System. The nation was in the depths of the Great Depression, and Warren's motives hinged on the practical. Although the once-famous ranch declined under the management of salaried caretakers during the previous decade, it nevertheless afforded an opportunity for Con Warren and his new bride, Nell, to make a living. Fresh from studying at the University of Virginia, Warren was no stranger to the ranch, or the ranching business. As a boy he had practically grown up at Deer Lodge, Montana, listening to the stories of the open range days told by Grandfather Kohrs and his partner and half-brother, John Bielenberg. Even as a young man, Con returned from school during the summers to work in the hay meadows of the family ranch that had once served as headquarters for one of the West's great cattle empires. After graduating college, Con took up residency on the ranch, working as a hand until manager Pem McComis retired. Even though the ranch was controlled by the Conrad Kohrs Company, headed by an old friend of the ranchman, Warren's selection as the new manager may have been influenced by family matriarch Augusta Kohrs.

The beginning of the Warren era heralded a rejuvenation of cattle raising on the old Kohrs and Bielenberg home ranch. With acreage now reduced to a small fraction of the former holdings, Con Warren recognized that additional land would have to be purchased if he were to be successful. More pasture was needed to support a much larger herd of cattle than the nearly static numbers that had characterized the operation for many years. The directors of the company agreed to acquire several parcels either contiguous to or near the home ranch for this purpose. Before long, the Kohrs Company owned 6,200 acres of land, of which 500 were devoted to hay meadows to provide winter feed for the stock.

Warren also turned to rebuilding the livestock herds. He had a small number of Herefords left from the former herd, along with a few old draft horses still bearing the Kohrs-Bielenberg brand. Con started by breeding registered Herefords with the two bulls then on the ranch. He also purchased additional heifers and bulls at extremely low depression-era prices and before long had a sizable herd of quality animals. Using his own money, Warren acquired a number of Belgian draft horses for use on the ranch. Rather than buying all of the horses he needed, he began raising his own Belgians, some of which he sold. Although Con clung to some of the time-proven traditional ranching methods he had learned from his grandfather, he demonstrated a flexibility in adopting progressive techniques, such as insemination of horses and scientifically mixed livestock feeds. By 1940, Warren had a highly successful stock raising operation that was nationally renowned for its registered Hereford cattle and purebred Belgian horses. [1]

|

|

Nell and Con Warren, 1934. (Courtesy Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS) |

Con invested heavily in the facilities at the ranch as well. The latter 1930s marked a period when several new buildings and corrals were constructed, and old ones were rehabilitated. Conservative in managing the ranch, Con always utilized the original ranch structures whenever possible, a factor that would bode well for the future. In 1937 it was reported that the ranch boasted numerous, "freshly-painted barns, new fence posts, and a neat, almost military-like order." [2] Among the recent additions was a new cottage-style house occupied by Con and Nell, a gift to the new bride from "Ohma," as Augusta was affectionately known. [3]

A new decade, however, brought changes to the operation. Whereas the horse business had become a staple of the Warren operation, and one that had helped him financially during down-trends in the cattle market, draft horses were quickly becoming a thing of the past. Farmers were turning to mechanization in their operations. Technology and mass-production increasingly brought machines within the financial reach of more farmers, who in turn could work larger acreages more efficiently. When an Iowa horse breeder offered to buy Con's Belgians, he did not hesitate in selling. Although he was emotionally attached to the horses, that part of the business no longer made economic sense. It was well that Con sold the horses when he did, because the World War II years witnessed an even more rapid acceleration of mechanization in American agriculture.

Within the few years after becoming manager of the ranch, Warren proved himself to be a rather adept manager. Clearly, he had revitalized the old ranch and had made it not only productive, but profitable. It was not making the company rich, by any means, but the modest profits portended better days to come. This in mind, Con offered to buy the home ranch from the Conrad Kohrs Company in 1940. The directors exacted a high price, but Con bought the property nevertheless. It was to be a heavy financial burden for many years to come. [4]

The end of the war saw the ranch solvent, though hardly better off overall than it had been four years earlier. Government price controls on beef during the war had severely limited Warren's profits. Operational costs, too, became almost overwhelming, precluding his ability to pay off the mortgage as quickly as he had anticipated. The modest profits realized went primarily to pay the interest on the contract. However, by selling the so-called "upper ranch" south of Deer Lodge in 1945, Warren was able to relieve himself of much of this burden and at the same time liquidate his assets to improve cash flow. [5] This was offset by a corresponding reduction in acreage, thus limiting the number of cattle he could support.

The Warren Hereford Ranch, as it became known under Con Warren's ownership, continued to produce high-quality purebred cattle. Building upon his already widespread reputation in the business, Con actively sought out new markets for his animals throughout the Pacific Northwest. He not only transported his cattle to various sales where prices would be highest, he promoted auctions at the ranch itself. The frequent visits to the old ranch by prospective buyers prompted Warren to construct new facilities, including corrals and a sale barn, east of the railroad tracks. At once, this relocation improved access and solved the perennial problems with deep mud experienced at the old ranch situated on the lower bench of the flood plain. From that time forward, Con's ranching activities were largely confined to the zone between the tracks and the highway.

Despite his earlier successes, Warren's solvency declined in the post-war era. In the late 1950s he suffered a major blow when it was discovered that the blood line of his registered cattle was plagued with genetic dwarfism. Eventually, weary of the struggle to make ends meet, Con decided to sell the herd in order to raise cash. It was said that he had only $10,000.00 after settling his debts. [6] He then resorted to raising common feeder cattle. Warren maintained a herd of about 350 animals for several years, until he again transformed his operations to raising and selling yearlings. In the late 1960s, Con limited his activities to feeding and marketing cows and calves. With the operation declining, the day was not far off when Con would have to consider the future of the ranch.

The effort to authorize Grant-Kohrs Ranch as a national historic site was rooted in the Mission 66 program, a ten-year renaissance designed to rehabilitate a flagging National Park System. Not unlike Con Warren's Hereford ranch, the National Parks languished in a financial vacuum during World War II. Visitation as well as Congressional support dropped sharply while national attention focused on the war effort. Much of what had been accomplished by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the way of roads, bridges, and buildings had seriously eroded during and after the war years when all aspects of park development, maintenance, and protection suffered from inadequate funding. Compounding this situation was a prosperous American public that thirsted to travel by automobile in the 1950s. It was estimated that one of every three persons in the United States would visit a national park in 1955. Faced with public use that had tripled since 1940, the National Park Service appropriation was actually less than it had been on the eve of the war. The Park System simply could not survive if something were not done, and quickly. [7]

Director Conrad L. Wirth devised a strategy for garnering a large special appropriation by proposing a bold program to rehabilitate the System. According to his plan, and a massive infusion of money, the national parks would be brought up to a satisfactory condition through an intensive ten year effort. Wirth's logic and persuasive powers convinced both the Eisenhower Administration and Congress to approve the program, labeled Mission 66, in 1956. [8]

Mission 66 created benefits beyond those aimed at rejuvenating the parks themselves. The Historic Sites Act of 1935 had provided for the National Survey of Historic Sites, a program involving the identification and evaluation of properties potentially having national significance. Those determined to have exceptional qualities might be considered for inclusion in the National Park System. The program brought together professionals from the fields of history, architecture, and archeology working in concert with state and local officials, as well as private owners. However, the shift in funding priorities during World War II caused the suspension of what had been a valuable tool in the process of preserving key sites representing the nation's heritage. The critical condition of the Park System in the post-war era would not permit the resumption of this inventory until Mission 66 was launched. The resurrected program was titled the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. [9]

In order that all important aspects of U. S. history and prehistory would be represented, Service professionals developed an outline of primary and sub-themes. Teams of appropriate personnel then prepared thematic studies to define the historical significance of these themes in the tapestry of the American experience. These teams subsequently identified properties nationwide that served to illustrate each theme. One such group, composed of historians Robert M. Utley, William C. Everhart, and Ray H. Mattison, was assigned the task of studying the role of the cattle industry within the larger context of westward expansion. Their 1959 report identified twenty-seven sites associated with the range cattle days, of which they recommended only six as having exceptional significance based on the established criteria for the survey. Among these was Grant-Kohrs Ranch, noted not only for the integrity of its structures, but because Conrad Kohrs was, "perhaps the greatest single figure in the cattle industry of Montana. [10]

Upon submission of the team report, those sites potentially eligible were presented to the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments. This board, composed of recognized authorities in several related fields of knowledge, had been established under the authority of the 1935 Historic Sites Act to consult with the Secretary of the Interior on such matters. After a lengthy deliberation, the committee recommended that the Grant-Kohrs Ranch, along with the JA Ranch (Texas), the town of Lincoln, New Mexico, and the Tom Sun Ranch (Wyoming), met the criteria for designation as National Historic Landmarks.

At the time, the act of announcing a property as a National Historic Landmark did not necessarily mean that it would be officially registered as one. The final designation for eligible properties was conferred when the property owner signed an agreement to maintain the historical character of the site, and consented to permit periodic inspections conducted by the National Park Service. Provided he chose this course, the owner would be presented with a certificate of recognition and a bronze plaque that could be publicly displayed at the site. [11] More than merely recognizing the national significance of such sites, however, the National Historic Landmark program provided for gratuitous technical assistance by Park Service preservation specialists. This element was basic to the concept of government assistance with preserving worthy sites, without actually acquiring them. Public access to the sites remained the province of the land owners.

Typical of his agrarian counterparts throughout the western United States, Con Warren was reluctant to invite what he may have perceived as needless government involvement, if not intervention, in his ranching business. In the rural West, even a strong appreciation for family heritage and regional history often do not equate with public use of one's property. It is not surprising , then, that none of the ranch owners named in the National Survey report elected to permit visitor access to their sites, although three of them, the J. A. Ranch, Grant-Kohrs Ranch, and the Tom Sun Ranch, did agree to the other provisions. [12] Thus, the cattle industry theme continued to be publicly interpreted by only two areas already in the Park System, North Dakota's Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial Park and the all-encompassing Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis. Neither of these, in fact, had as its primary focus the cattle industry. Nor, in fact, was there enthusiastic support within NPS for acquiring additional areas to represent that theme. According to one Service historian, "Traditionally, the National Park Service has had a negative attitude toward the cattle industry theme . . . grazing has been looked upon as an adverse use in most . . . parks." [13]

By the mid-1960s, Con Warren was in his middle years by this time and had accepted the fact that neither of his children would pick up the reins of running the ranch. Yet, Con possessed a strong sense of pride in his pioneer heritage and the contribution of his forebears to Montana's cattle industry. Without anyone in the family willing to carry on the tradition by working the ranch, there was little point in maintaining the business. Con began to think in terms of somehow preserving the place beyond his lifetime, perhaps as a museum for Deer Lodge. He and his wife discussed the possibilities from time to time, but were unable to arrive at a solid solution until 1966, when Nell suggested approaching the National Park Service. The ranch, after all, had been officially inspected and recognized for its significance. "We wrangled about it for thirty days before I finally sat down and did it," Con remembered in a later interview. "So, if it hadn't been for her, we wouldn't be standing here right now." [14]

Warren's subsequent communication with the Montana congressional delegation prompted Chester C. Brown, chief of planning in the Washington office, to request assistance from nearby Yellowstone National Park. Accordingly, Superintendent John S. McLaughlin assigned historian Aubrey C. Haines to make an on-site investigation of the area with a view to its potential for becoming a unit of the System. Haines at that time was serving a stint as acting ranger-in-charge at Big Hole Battlefield. Traveling to the ranch on July 28, 1966, he met with the Warrens and made a cursory inventory and evaluation of the structures. It became apparent to Haines during their conversations that despite Con's expression of lofty motives for parting with the ranch, he was willing, even anxious, to sell. Haines recommended to McLaughlin that, "further study of the area" was warranted because of the "good condition of the premises, their obvious integrity . . . and the possibilities for a meaningful presentation to the public." [15] However, Haines would confide years later that the place impressed him, "as a kind of run down, remnant of a ranch" that was going to require a lot of money to develop. [16]

Communication now established with the Service, Warren wrote directly to the Washington Office during the following January to bolster his case for bringing the ranch under the protective umbrella of the National Park Service. Con wanted to know if the ". . . Department would be interested in developing a museum or recreational area at this Historic Site," at the same time offering his complete assistance. [17] Assistant Director Theodor R. Swem responded in a supportive tone, asking if Warren had given any thought to, "what measures might be helpful in assuring preservation of the ranch buildings and collections." Swem also queried Warren as to whether he had in mind a time schedule for selling the property, even though his letter had not indicated any particular urgency. The Washington official concluded on a note of caution that all of the usual factors of suitability and feasibility would need to be investigated, "before we can take a position in regard to the ranch's potential as an addition to the National Park System." [18]

In his missive of a few weeks later, Con reiterated the obvious need to set aside the 1862 Grant-Kohrs house. Beyond that, however, he was uncertain just what the NPS might consider as historically significant for inclusion in a national historic site and suggested that it might be appropriate for professionals to "clarify the boundaries of the Kohrs-Grant ranch." Con candidly admitted that he did not have the financial resources to preserve the ranch, moreover he wished to retire in the not-too-distant future. With those considerations in mind, he was willing to negotiate the sale of the ranch at any time. [19] Russell E. Dickenson, chief of new area studies and master planning (and future NPS director), subsequently advised Warren that his office was already encumbered with a heavy workload, therefore it would be impossible to undertake a study at Grant-Kohrs for some time. He did offer the promise that his staff would conduct the project as soon as possible. [20]

Good to his word, Dickenson saw to it that historian Merrill J. Mattes and architect John Calef, both from the San Francisco Planning and Service Center, paid a visit to the site in September 1967a. [21] Mattes's report favored NPS acquisition, though he outlined several conditions that would have to be weighed very carefully. There was no question in his mind that the ranch was a historically important site; that already had been confirmed by its National Historic Landmark designation. While Mattes was a seasoned academic historian, he recognized the potential impacts of a new form of interpretation termed historical animation, or "living history," as it became known in the NPS, that was catching fire throughout the nation [22] By the late 1960s, there were many "living farm" demonstrations active in the throughout the United States. Mattes challenged the Service to consider whether or not it wanted "to embark on an expanded program of living demonstration areas, including a western ranch holding" and, if so, to make a determination whether the Grant-Kohrs Ranch was "the most feasible candidate for such representation in the National Park System." Of a more practical nature were the questions of whether Warren would sell at a reasonable price, making a donation of the historical objects and records, and whether Congress could be convinced to pay the high price commanded by prime agricultural lands. Mattes estimated that the total cost for acquisition and development would exceed one million dollars. [23]

The wheels of bureaucracy turned slowly and it was not until early in 1969 that Swem notified Warren that while the Service had not lost interest in the ranch, it would be some time before a master plan could be prepared. Swem explained that this planning exercise was basic to the preparation of a specific proposal for consideration by the Secretary of the Interior and the Advisory Board. Funding, he pointed out, simply was not available to accomplish this. He added that an even greater hurdle in the process would be the act of Congress necessary to authorize the area, along with a funding appropriation. [24]

This was a grim forecast that might have dashed any hopes Warren had for the quick sale of his property, were it not for Swem's suggestion that he consider an arrangement with the National Park Foundation. It was for just such circumstances that this organization had been chartered by Congress. The officially-sanctioned partner of the National Park Service relied solely on private donations to acquire options on identified critical lands, and to hold them in trust until congressional funding was forthcoming. Thus, tracts of land vital to Park Service interests, that might otherwise be lost to prior sale or degraded by adverse impacts, could be protected in the interim.

This was clearly not the answer Con wanted to hear. He initially ignored Swem's suggestion, choosing instead to turn up the heat under the Park Service. Writing to Swem in July 1969, the businessman in Warren came to the fore. His frustration with what he perceived as a needlessly slow process surfaced as he pointed out to Swem that very little had been accomplished in the two and one-half years of discussions. In a "fish, or cut bait" ultimatum, Warren told Swem that he had received a very attractive offer to sell the whole ranch to another party and that he was running out of time to respond. "If by [September 1, 1969] the Park Service has not made a move to acquire . . . the Historic Site," Warren wrote, "I would have only one alternative and that would be to dispose of the antiques and artifacts and sell the whole property as a ranch." [25]

Whether or not Con was bluffing may never be known, but one thing is certain -- this no-nonsense rancher knew how to get the attention of the National Park Service. The very next month Ralph Lewis, chief of the Branch of Museum Operations, found himself in Deer Lodge, Montana. There he spent a full day with Con surveying the contents of the 1862 ranch house and several of the outbuildings. That Lewis was mightily impressed is evident in his report. He noted, once again, that the entire site possessed a high degree of integrity in its magnificent collection of site-specific artifacts, its original structures, and in its landscape. Here at an old-time working ranch, he noted, "The cowboy and other usually over-romanticized elements of the wild West fall into proper perspective and seem to gain impact in the process." [26] This visit seems to have either appeased Con for the moment, or belied his threat. Whichever it was, the ranch remained unsold.

In following months, the National Park Foundation opened communication with Warren, but the road was a rocky one initially. Warren hosted Robert R. Garvey, assistant secretary for the National Park Foundation and executive secretary for the Advisory Council , at the ranch late in 1969. At that time the two reached agreement on major points. Garvey also initiated an appraisal of the ranch lands. [27] Yet, upon his return to Washington, Garvey was stunned to learn that Warren had declared the negotiations to be at an end. Once again, insufficient basic data and the absence of a defined concept plan deprived the players of a foundation for the frank discussions that Con Warren expected. Neither party understood just which tracts of land were considered significant for inclusion in the proposed historic site. Further, the Warrens rejected the idea of being granted a life estate on their home and the parcel of land encompassing the modern ranch operation east of the railroad tracks. Garvey attempted to rescue the relationship as best he could, blaming the breakdown on "a lack of information regarding requirements, both ours and yours." [28] He encouraged Con to reconsider his stance, assuring him that the Foundation had not changed its mind about the significance of the ranch.

Con's favorable response to Garvey's entreaty may well have been in deference to an ailing wife's desire to see the ranch preserved as a public historic site. If he was still considering a sale to anyone other than the government, Warren made no further mention of it. He quickly submitted to the Foundation and the NPS a revised proposal containing several alternatives for protecting the historic ranch, as well as preserving a viable portion of the Warren Hereford operation. [29]

After teetering on the brink of collapse for months, the negotiations suddenly made a turn-around, due in no small part to Bob Garvey's diplomacy. He and Con seem to have established a mutually respectful working relationship during Garvey's visit to the ranch. By the first of April 1970 Warren had firmed up his earlier proposals for dividing the property to accommodate both park and ranch needs. The essence of this plan was to sell thirty-five acres containing the historic home ranch buildings, plus an additional ten acres east of the tracks, south of Con's house, for visitor parking and access. Additionally, Warren would grant easements on adjacent lands, the whole priced at $311,000.00. A separate contract would be negotiated for the antique furnishings and ranch equipment based on appraised value. Warren's attorney in Helena, Peter Meloy, prepared the formal offers and forwarded them to Garvey, suggesting at the same time that Garvey should plan to meet with him and the Warrens as soon as possible to work out the details. [30]

After this meeting took place, late in June of 1970, Garvey returned to his Washington office where he conferred with John D. McDermott, his assistant secretary on the Advisory Council. Garvey was faced with the critical decision of having proposals for two eligible sites, Carousel Park in Maryland and Grant-Kohrs Ranch, but money enough to acquire only one. When asked for his recommendation, McDermott immediately suggested the ranch. He reasoned that the Park System had no area devoted exclusively to representing the cattlemen's empire, a sub-theme in the recently adopted National Park Service Plan. The concept for such a plan had originated in 1964 with Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, who had advanced the idea that the Park System should be expanded. His successor, Walter J. Hickel, likewise became convinced that there were "serious gaps and inadequacies which must be remedied while opportunities still exist if the System is to fulfill the people's need to see and understand their heritage . . . ." [31] NPS Director George Hartzog and his staff capitalized on this opportunity by designing the plan around a thematic framework for expanding the System's cultural parks through careful evaluation of appropriate sites and buildings. Accordingly, the plan encouraged controlled expansion of the System by outlining historical themes that ought to be represented by sites meeting specific criteria of significance and integrity. These served as an objective method for screening out unwanted or marginally-significant parks, so often imposed upon the NPS by delegates eager to promote local economies, and garner support for the next election. At the same time, the process exposed a wide range of deficiencies in themes that were either under-represented, or not represented at all. [32] Hartzog had guidelines in place, coincidentally, by the spring 1970. Considering the Department's emphasis on fleshing out the System, Garvey the politician saw a serendipitous advantage in promoting an under-represented type. [33]

Garvey immediately initiated procedures for finalizing the deal to acquire Grant-Kohrs Ranch. Following a legal review of the provisions contained in the sale offer, the Foundation's attorneys deliberated with Meloy until a tentative agreement was reached in August. The decision turned on a key factor -- the Warrens' decision to donate, rather than sell, the artifact collection. These favorable developments influenced the Advisory Board at its October 1970 annual meeting to "emphatically recommend that the National Park Service negotiate immediately" with Warren to acquire the ranch. [34] In the deal that was struck, the Warrens relinquished 130 acres in fee, plus 1180 acres of easement, for a single payment of $250,000.00. Although a meeting to finalize the deal had been scheduled early in September, the closing was delayed until November 13, 1970. [35] With that, the papers were signed and the legendary ranch passed out of family hands for the first time in 104 years. No doubt Con Warren had some feelings of regret when the time actually came to sign away the place, but he would later admit that, "really, that's kind of what saved my bacon is when I made that sale . . . otherwise, I think I'd be flat broke now, maybe worse than flat." [36] Con's decision was probably the best compromise he could have negotiated; the ranch was preserved, he retained his home and business, and there was cash to pay his debts.

Separate from the land sale was an agreement executed the same day between the Warrens and the National Park Foundation (NPF). The document was intended to guide the use of the area by both parties during the interim period. A provision of this accord called for an inventory of the historical objects on the site, which were to be donated to the NPF rather than purchased. Another was significant for authorizing National Park Service personnel, acting on behalf of the Foundation, to assume responsibility over the area. [37]

One of the members of that first reconnaissance party was Park Ranger John R. Douglass, then serving as the West District naturalist in Yellowstone National Park. Douglass conducted an informal inspection of the site and, as a result, developed some recommendations for the immediate future of the ranch. Besides the need for researching the buildings, he saw an urgent need to establish an official presence at the site. He observed that Con Warren had "shown remarkable patience in dealing with the multitude of Park Service personnel," but Douglass felt it was time to designate one individual as coordinator for the area. Too, he recommended that a caretaker be assigned to live on-site for protection and to carry out minor maintenance work. [38]

|

| Vernon E. Hennesay (front row, right) with group, Yellowstone National Park. (Courtesy Yellowstone NP) |

The staff at Yellowstone National Park moved quickly to act on the caretaker issue. Early in December, arrangements were completed to move a mobile home from Yellowstone to the ranch. Tom Pettet, a Butte, Montana native and member of the Mammoth District maintenance crew, was detailed for the assignment. Since Pettet shared quarters at the park with his mother, both were relocated to Grant-Kohrs. By mid month, Acting Midwest Regional Director Robert L. Giles, headquartered in Omaha, was able to report to Director Hartzog that the site was occupied and that utilities connections had been made with the city of Deer Lodge. [39]

For a few weeks following the purchase, Douglass continued in his liaison role, making community contacts in Deer Lodge and laying the groundwork for housing Pettet at the ranch. Vernon E. Hennesay, the assistant superintendent for special services at Yellowstone National Park, also had become involved by virtue of his catch-all staff position. It became increasingly apparent that a single key person should be designated to coordinate communications both within the NPS and with outside organizations. Issues such as utilities connections, fire protection agreements, and basic maintenance priorities were already arising that required the attention of an employee vested with authority to act on them. Furthermore, Pettet's placement at the ranch raised questions about supervisory responsibility. Douglass complained that, "The man does not know what he is supposed to do. Who is to tell him?" Acting on Douglass's suggestion, Yellowstone Superintendent Jack K. Anderson named Hennesay to head the effort. [40]

The dawn of the new year found the ranch entering a new phase in its transformation from cattle operation to historic site. During Con Warren's protracted negotiations with the NPS and the Park Foundation, some area residents had scoffed at the notion of his selling the ranch to the U. S. Government. Many in the community perceived the deal as nothing more than a financial scheme for Con's benefit. This was probably a reflection of the Warrens' unpopularity with some people stemming from the couple's private nature, seasoned with an element of envy. While there can be little doubt that Warren saw in the sale an opportunity to secure his future, he also was genuinely interested in establishing a permanent legacy devoted to the days of the open range, as illustrated through his ancestors. [41]

Once the ranch was purchased by the Foundation, however, the voices of the nay sayers were suddenly replaced by community leaders lauding the noble effort. This shift in attitude was evident when two officers of the Deer Lodge Chamber of Commerce solicited U. S. Senator Mike Mansfield for his support of proposed legislation to officially authorize the site. "We feel that such an area is desperately needed to alleviate the pressure on the two National Parks in the State and would be a substantial aid to the economy . . . ," they wrote. [42] Mansfield's counterpart, Senator Lee Metcalf, joined him in querying Director Hartzog for a report on the status of NPS plans for the ranch. The Service could respond only that planning would have be revised with a view to the property that was actually purchased, as opposed to the initial concept of acquiring a tiny holding of only 45 acres. However, the Service could take no particular action until a master plan was completed. [43]

The purchase of the Warren Ranch by the National Park Foundation gave renewed impetus to formal planning for the area. Just before Christmas 1970, Robert L. Giles, acting Midwest Regional Director of the National Park Service, notified Hartzog that it was urgent that NPS move forward on this project. He left unsaid what Hartzog already knew; the politically powerful Mansfield was not to be denied, Giles declared that since funding for new area studies was critically short, the region would defer two other projects in favor of Grant-Kohrs Ranch. Assistant Director Joe Holt thereupon suggested that the process might be further expedited by a request for money from the director's reserve, but that proved unnecessary when the Western Service Center found massive funding to underwrite several studies, including one for the ranch. By March, 1971 both the funding and a planning directive had been approved. A team was slated to meet in Deer Lodge on May 3 to begin work on the all-important plan. Significantly, the Park Service officially settled upon "Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site" as the formal name for the proposed area. [44]

With a growing public constituency now behind the creation of a national historic site, the Montana delegation initiated a request for the NPS to draft the enabling legislation for a House of Representatives committee hearing scheduled for late in April, 1971. [45] This was timely, in view of Director Hartzog's aggressive acquisition program to flesh out the historical wing of the System, according to the comprehensive National Park System Plan.

Grant-Kohrs Ranch was suddenly thrust in the fast lane of the legislative process. There was not time, of course, to complete a master plan within the deadline imposed by Congress. Legislative counsel for the Department of the Interior, Frank Bracken, forwarded the draft authorization bill to Mansfield's office on May 24. Although this draft called for a limitation of 2,000 acres of land to be acquired for the site, that amount was later reduced to a maximum of 1,500 acres. The Midwest Regional Office also supplied the senator with estimates for personnel and support costs for a five year period. [46] Following closely on the submission of these estimates, the Park Service sent copies of a hurriedly prepared preliminary master plan to the Washington Office in preparation for a site visit by the House Subcommittee on Interior and Insular Affairs in mid-August. The committee wanted to "get a better view and a better understanding of what the area is," according to site coordinator Vern Hennesay, [47]

Regardless of the House committee's timetable, Mansfield and Metcalf formalized and introduced their bill (S .2166) on the Senate floor on June 28, 1971. In his speech, Mansfield appealed his colleagues that, "Opportunities of this kind are very rare and I hope that the Congress will be able to expedite considerations of this legislation so that the National Park Service might proceed with the development of this site." Even though the Interior Department had not yet been asked for its opinion on the legislation, Deputy Director Tom Flynn prepared a draft favoring the bill, knowing the Senate committee would request it on short notice. [48]

The congressional committee's visit was a serendipitous opportunity for the NPS and the Deer Lodge community to advance their case for authorizing the site. The congressional inspection of Grant-Kohrs Ranch was one stop on an itinerary that included visits to two other proposed parks, Golden Gate recreation area in California and a recreation area on Snake River in Idaho. Preparations for the event moved into high gear to ensure that the Washington visitors were favorably impressed. Vein Hennesay coordinated plans with the Deer Lodge Chamber to host a luncheon for the delegates and approximately 100 community leaders and residents on the old Kohrs ranch house lawn. The committee, including Representatives Roy Taylor, Joe Skubitz, Don Clausen, Jim McClure, and John Melcher, arrived by chartered airplane on August 11. The Park Service was amply represented by Deputy Director Tom Flynn from the Washington Office, Regional Director Len Voltz, and Yellowstone Superintendent Anderson. Hennesay and Douglass led an orientation tour of the site, highlighted by a walk through the ranch house, for the congressional party and NPS central office staff The affair had the desired effect. In addressing the group, Montana Congressman Melcher pledged his full support to "prompt legislative action" on the ranch. Hennesay later gauged the committee's reaction as a positive one, noting that, "We are sure there is no doubt in their minds . . . of the value in having the Grant-Kohrs Ranch established as an historical site . . . ." [49]

|

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

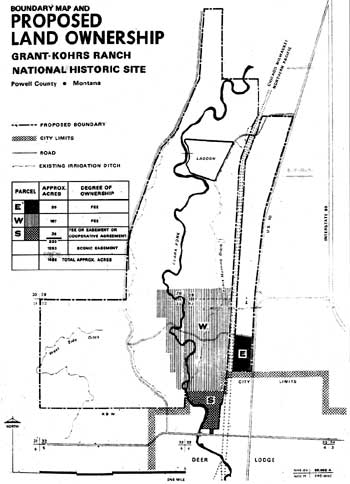

In the months following the committee's visit, the staffs at the Washington Office, the Midwest Regional Office in Omaha, and the newly-organized Service Center in Denver devoted full attention to preparing legislative support data for the ranch. [50] By the end of October 1971, all of the figures for land acquisition, easements, and development, in addition to projected personnel costs, had gone forward for congressional consideration. The Service finally proposed purchasing 208 acres in fee, and negotiating easements on an additional 1,280 acres to protect the integrity of the site. The total cost estimate for the first year of operation was $350,000.00 [51]

Deeply-rooted Kohrs family ties with Montana politics promoted strong bipartisan support for setting aside the ranch as an historic site. In July 1971, Congressman Dick Shoup weighed in with his own version of a House bill bolstering the Senate legislation framed by Mansfield and Metcalf a month earlier. [52] There was little surprise when the draft cleared the already thoroughly-buttered Interior and Insular Affairs Committee on February 10, 1972. "All of the hard work we have gone to get the Grant-Kohrs Ranch designated . . . is now paying off," Shoup proclaimed to the press. Hearings on the bill were slated to be held near the end of April. [53] Once past the hurdle of the congressional committee, albeit a low hurdle in this instance, the house bill was in the home stretch for consideration by Congress.

During the interim there was little that could be done by either the Park Service or the Deer Lodge community beyond continuing to beat the drum of support. Townsfolk now enthusiastically embraced the idea, even those who had previously suggested that Con Warren might be showing signs of senility in thinking the ranch had any significance. [54] The Chamber of Commerce, slow to back Warren initially, eagerly began calculating the financial benefits to be reaped from a major tourist attraction. At Chamber meetings and in coffee shops, area residents discussed how park visitors would need expanded lodging and restaurant facilities once the site was in operation. The forecast of an economic boom was no doubt fueled by the wildly speculative predictions that some 220,000 to 240,000 tourists would visit the ranch each year. [55] A national historic site on the edge of town, it was predicted, would be the salvation of Deer Lodge. "They were all going to get rich off of it," one former park employee recalled. "They thought it was going to be another Yellowstone." [56]

While the politicians competed for the laurels to be reaped by sponsoring the enabling legislation, the strategy of having separate bills before the two bodies of Congress had its advantages. Senator Metcalf served in a key position as a member of Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. His influence was vital to winning committee approval of the Mansfield-Metcalf Bill, S. 2166. Approval of the parallel proposals by both House and Senate committees practically guaranteed final passage with few alterations, In August the two pieces of legislation were considered and voted on by the respective houses, the Senate version passing easily on August 10, with Shoup's to follow a few days later. The latter was delayed when it was discovered that the number of acres for acquisition was not specified in the document. Consequently, the House bill had to be laid before the Senate for resolution, The Senate voted to adopt the less specific wording in the House version, which established a land ceiling of 2,000 acres, without limiting the fee acquisition to 208 acres. Once that was done, the amended and approved Senate bill was sent to the White House. The legislation eventually caught up with President Richard M. Nixon at his home at San Clemente, California, where he signed Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site into law on August 25, 1972. His signature officially put the Park Service in the cattle business. [57]

Before year's end the National Park Foundation conveyed its interests in the ranch to the NPS, In turn, the Service reimbursed the Foundation $257,544.00, the full amount of its investment, plus interest and administrative costs. That was the final action necessary to place Grant-Kohrs Ranch firmly and forever in the hands of its new stewards. [58]

The momentous events in San Clemente and Washington had little immediate effect on activities at the ranch. The site would remain closed to the public for the next two or three years, a disappointing revelation to the Deer Lodge community. "We want to discourage visitors now as we are not ready for them," Vern Hennesay told listeners at a Chamber luncheon within a month after the signing. "So please don't give it too much publicity." [59] While his comments may have dampened community enthusiasm, Hennesay was only being realistic. There was still no funding approved for the new park. The buildings were in no condition to be accessed safely, and the lack of visitor facilities and staff made it impossible to accommodate the public.

In the two years since National Park Service personnel had first occupied the site, only the most basic of maintenance activities had been carried out. "One man can only accomplish so much," Hennesay lamented in December 1972, adding that he would have to "continue operating on a very slim budget of whatever we can 'bootleg' from Yellowstone until after June 30." [60] Tom Pettet and his successor, Edward Griggs, were therefore limited to organizing and storing the many years of accumulated ranch material, as well as disposing of refuse scattered about the property. They mitigated the danger of fire somewhat by keeping the grass and weeds mowed around the grounds. Crude, stop gap means were employed in propping up sagging roofs and keeping the weather out of the decaying buildings by fixing doors and replacing broken window panes. Under Hennesay's direction, the caretakers attempted to provide the wagons and other ranch equipment with the best storage possible within the existing primitive conditions. It would remain for NPS professionals, and a large influx of money, to put the ranch back on the road to recovery.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grko/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006