|

Grand Portage National Monument Minnesota |

|

NPS photo | |

Kitchi Onigaming—The Great Carrying Place

The Voyageurs—Backwoods Navy of Canoemen

Voyageurs—French for "travelers." The hardy French Canadians were more at home in birchbark canoes than on land. Their reputation for working energetically without complaint, chanting nostalgic French songs as they paddled, and vigorously defending the honor of their profession has earned them the status of folk heroes. "There is no life so happy as a voyageur's life," reminisced one who retired after 41 years.

But in return for adventure and camaraderie they sacrificed comfort, health, and permanent homes. In the employ of fur-trading corporations they labored to meet European demand for beaver skins. While they fueled a young nation's economy and opened new territory, the voyageurs often fell victim to disease, collapsed along grueling portages, or drowned in the icy waters of the Canadian wilderness.

A water network linked Montreal, capital city of the Great Lakes fur trade, with western Canada's fur-bearing animals. Where streams were unnavigable, canoemen carried boats and cargo over a portage, or trail. Named Kitchi Onigaming by the Ojibwe and "The Great Carrying Place" by French explorers and missionaries sometime after 1722, the Grand Portage bypassed rapids on the lower Pigeon River. It was the throughway to Canada's prime fur country. In 1784 Grand Portage became headquarters of the North West Company, owned by Highland Scots. To transport furs the company hired a backwoods navy of voyageurs.

The company's post on Grand Portage Bay was a convenient meeting place for the voyageurs. They had evolved into two groups based on geography: the north men, or "winterers," and the Montreal men, also called "pork-eaters." Late in July brigades of north men set out from Grand Portage for trading posts in the Canadian north. Trade goods bought furs from Native Americans. Like tobacco in colonial Virginia, beaver furs were currency in the Northwest. Ultimately they were fashioned into elegant felt top hats for European and American upper classes.

Through the harsh winter the north men traded out of their lonely posts. With the break-up of the ice in about mid-May they returned to the Grand Portage. Meanwhile the Montrealers propelled their craft up the Ottawa River and westward across the Great Lakes. Two months later they joined their counterparts for the annual Rendezvous. At this company-sponsored event the north men exchanged furs for trade goods and supplies furnished by the Montreal men, partners struck deals, and Europeans and Indians alike engaged in raucous entertainment.

Afterward the winterers headed to the backcountry, and Montreal men paddled canoeloads of furs eastward. The Grand Portage trading cycle continued until 1803 when the company moved upshore to Fort William. By 1821 the portage had fallen into disuse. As the fur trade lost momentum toward the mid-1800s—fashions changed and beaver populations diminished—the hardworking, rambunctious voyageurs found their profession becoming obsolete.

Birchbark Canoes

On foot voyageurs might have trudged 15 or 20 miles a day. By canoe they

covered 60 to 80 miles and hauled tons of cargo. Were it not for the

lightweight, speedy birchbark canoe, an invention of the region's

Indians, North America's fur-trading empire would not have existed on

such a vast scale.

Canoes used by the winterers on narrow, rapid waters were about 25 feet long and carried four to six voyageurs. Lake canoes about 10 feet longer carried twice as many Montreal men and up to 8,000 pounds of cargo. Both were built from large sheets of birch bark—lashed with split spruce roots to a wooden gunwale, then lined with cedar planks and stabilized with ribbing. Spruce pitch waterproofed the seams. No hardware was used.

As practical as these canoes were, they were not indestructible. Easily punctured bark skin required constant care and frequent repairs. Many a voyageur spent his evenings patching a canoe before crawling underneath to sleep.

Native Americans

The arrival of French explorers in the mid-1600s began a new era for the few hundred Cree and Ojibwe who lived at Grand Portage, as well as the Sioux, Blackfoot, Beaver, Chipewyan, and Slave Native Americans of the Canadian Northwest. Superb canoeists and hunters, they practiced their ancient skills as vital participants in the international fur trade. They furnished sought-after pelts and equipment and knowledge essential to the voyageurs, who spent most of the year in the lands the Indians had inhabited for generations. Tribesmen taught the newcomers to build canoes from birch bark and guided them along the water routes into the wilderness. Sometimes the relationship between Indians and new settlers went beyond business, and many voyageurs married Indian women.

Voyageurs offered the Indians exotic new items, curiosities at first that eventually became necessities. Glass beads from Venice decorated ceremonial clothing. Wool blankets and woven cloth replaced animal skins. Iron implements—kettles, axes, firearms, and traps—became indispensable, as did distilled spirits. By the 1800s European culture had left its indelible mark on the lives of even the most remote people.

The North West Company

In 1763, after the French and Indian War, France ceded Canada to Great Britain. Under British rule just about anyone was allowed to extract the natural wealth of the Canadian Northwest. Those with foresight pooled their resources and formed wilderness corporations. The North West Company was formed in 1784. Company head Simon McTavish and his partners, canny businessmen with a ready eye for expansion, inspired Washington Irving's description, "lords of the lakes and forests." Canoemen themselves, these partners accompanied voyageurs into the wilderness or back to Montreal.

The enterprise succeeded mainly because of the expedient waterway into the Canadian interior via the Grand Portage. Voyageurs paddled far into the wilderness, intercepting Indian hunters before they had traded away furs to the competition. Intense rivalry heightened in the early 1800s as the partners vied with the Hudson's Bay Company for business, and profits diminished for both. In 1821 the two merged, putting an end to the sometimes violent feud.

A Guide to Grand Portage

From 1784 to 1803 Chief Director Simon McTavish and his North West Company partners ran the most profitable fur trade operation on the Great Lakes. The company's inland headquarters was located at Grand Portage, the largest fur trade depot in the heart of the continent. Sixteen wooden buildings stood inside the palisade, including a business office, warehouse for trade goods and furs, food storage buildings, and living quarters for the partners and clerks.

This was also the site of Rendezvous, an annual gathering awaited through the long winter season by everyone connected with the company. Hundreds of voyageurs spent the better part of July camped outside the palisade. "The North men live under tents," wrote explorer Alexander Mackenzie, a company partner, "but the more frugal pork-eater [Montreal man] lodges beneath his canoe."

Food was plentiful and liquor flowed freely—at least for those willing to part with wages just received for the past year's work. Long-standing rivalries sometimes sparked fistfights and exploded into brawls, landing participants in the company jail.

On the final night of Rendezvous, partners and guests feasted and danced in the Great Hall, while outside voyageurs and Indians staged their own celebration. Grand Portage Ojibwe donned ceremonial garb, and canoemen sported trademark apparel: plumed caps, bright jackets, and fringed sashes. When Rendezvous ended, the voyageurs took up their paddles and headed for another season of travel and trade.

The post was abandoned in 1803 after the North West Company, owned by Scots but operating on American soil, relocated northward to avoid the complications of citizenship, licensing, and import duties. When explorer David Thompson surveyed the area nearly 20 years later, he saw only the remains of clover-covered foundations. The Grand Portage itself was obscured by vegetation and fallen trees. In 1958 the Grand Portage Band of Minnesota Chippewa donated the land that became the national monument that same year. Written accounts and archeological excavations provided information for reconstructions. Interiors are furnished 1797-style.

The Great Hall, inactive most of the year, came to life as fur traders converged in late June for Rendezvous. Company partners, clerks, and Indians talked business in the Great Hall by day and dined in the evening. Food was prepared in the kitchen, behind the Great Hall.

During the company's heyday all trade goods going to outposts in the Canadian fur country and all furs bound for Montreal were funneled through Grand Portage. The cedar-picket palisade was designed mainly as secure storage for extensive inventories of goods rather than as defense against attack. You may climb the lookout tower for a view of the grounds and Lake Superior.

Outside the palisade is a reconstructed warehouse. Its location suggests the original building might have belonged to an independent trader. It also may have provided extra storage space when warehouses inside the palisade were full. Today the building displays historic items, including birch-bark canoes built by traditional methods.

A fur press converted bulky furs into easily handled cargo. About 60 beaver pelts piled atop four binding cords and sandwiched in burlap or muslin were pressed and tied into a compact 90-pound bale.

Planning Your Visit

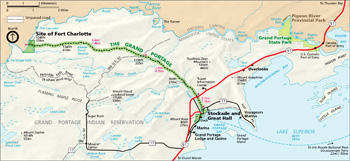

(click for larger maps) |

Getting Here Grand Portage National Monument is on Lake Superior's northwestern shore, seven miles south of the United States-Canada border and 36 miles north of Grand Marais, Minn. The park is east of Minn. 61.

Begin Your Visit The Heritage Center, open year-round except major winter holidays, has information, exhibits, films, and a bookstore. There is no entrance fee to the park.

Things To See The reconstructed depot area (Stockade and Great Hall) gives you a view of life at Grand Portage in the late 1700s. The historic buildings are open daily late-May through mid-October. Other park areas, including the Grand Portage trail and the Ojibwe village, are open year-round.

Picnicking, Food, Lodging A picnic area is within walking distance of the depot; roadside parking available. Find groceries at the Trading Post and food and lodging at Grand Portage Lodge.

Accessible Buildings and grounds are accessible for visitors in wheelchairs. Service animals are welcome.

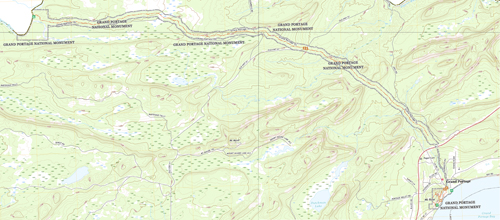

The Grand Portage Voyageurs carried two Pigeon River 90-pound packs along the 8½-mile portage between Lake Superior and Fort Charlotte, the company's smaller storage depot on the Pigeon River. Today the Grand Portage trail is open year-round to hikers and backpackers. In winter crosscountry skiers enjoy the woods and rolling terrain. There are no modern facilities on the trail. Campers must register in advance for the primitive campsite at Fort Charlotte; primitive camping is free.

Mount Rose Mount Rose trail begins across the road from the depot area and ascends 300 feet to the hill's summit. Get a brochure at the trailhead.

In summer you can take a ferry from Grand Portage to Isle Royale National Park. Ask staff for details.

Related Sites Old Fort William, Voyageurs National Park, Fort Michilimackinac, and Pine City Wintering Post are historic fur trading sites. The Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul has fur trade exhibits. Check websites.

Safety First Emergency help is a long way off. Remember, your safety is your responsibility. • Be careful crossing roads. • Watch your step on uneven surfaces. • Watch your children: the dock area can be dangerous, and the lake is extremely cold. • On the portage, wear sturdy footwear and carry plenty of water. • Mosquitoes and flies are abundant in June and July. • For firearms and other regulations check the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

Documents

A Report on Archeological Investigations Within the Grand Portage Depot (21CK6), Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota: The Kitchen Drainage Project (HTML edition) (Vergil E. Noble, 1990)

A Survey of Beaver Ecology in Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (D.W. Smith and R.O. Peterson, 1987)

Acoustic Amphibian Monitoring, 2019 Data Summary: Grand Portage National Monument NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/GLKN/NRDS-2022-1381 (Gary S. Casper, Stefanie M. Nadeau and Thomas B. Parr, December 2022)

Acoustic Monitoring Report: Grand Portage National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NSNSD/NRR-2021/2273 (Emma Brown, July 2021)

Acoustic Monitoring for Bats at Grand Portage National Monument: Data Summary Report for 2016–2019 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/GLKN/NRDS—2021/1314 (Katy R. Goodwin and Alan A. Kirschbaum, February 2021)

An Administrative History: Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (HTML edition) (Ron Cockrell, 1982, revised 1983)

An Archeological Survey of Development Projects Within Grand Portage National Monument, Cook County, Minnesota (HTML edition) (Vergil E. Noble, 1989)

An Historical Study of the Grand Portage: Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (Alan R. Woolworth, 1993)

Aquatic Studies in National Parks of the Upper Great Lakes States: Past Efforts and Future Directions NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2005/334 (Brenda Moraska Lafrancois and Jay Glase, July 2005)

Archeological Excavations at Grand Portage National Monument, 1962 Field Season (Alan R. Woolworth, December 1968)

Archeological Excavations at Grand Portage National Monument, 1963-1964 Field Season (Alan R. Woolworth, December 1969)

Archeological Excavations at the Northwest Company's Depot, Grand Portage, Minnesota, in 1970-71, By the Minnesota Historical Society (Alan R. Woolworth, 1975)

Archeological Excavations at the Northwest Company's Fur Trade Post, Grand Portage, Minnesota, in 1936-1937 (Alan R. Woolworth, 1963)

Archeological Inventory and Testing of New Pathways, Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 105 (Jay T. Sturdevant, 2008)

Awaiting the Call: Historic Sites Monitoring and Preservation at Fort Charlotte (21CK7), Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (©Andrew E. LaBounty, Master's Thesis, University of Nebraska, November 2010)

Bat Monitoring Protocol for the Great Lakes Inventory and Monitoring Network — Version 1.0 (NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GLKN/NRR-2020/2126 (Katy G. Goodwin, May 2020)

Bioaccumulative Contaminants in Aquatic Food Webs in Six National Park Units of the Western Great Lakes Region: 2008-2012 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GLKN/NRR-2016/1302 (James G. Wiener, Roger J. Haro, Kristofer R. Rolfhus, Mark B. Sandheinrich, Sean W. Bailey and Ried M. Northwick, September 2016)

Co-Managing Gichi Onigaming — "The Great Carrying Place": Administrative History of Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (Theodore Catton and Diane L. Krahe, 2023)

Decarbonization Plan Summary: National Parks of Lake Superior (Energy Environmental Economics, Inc. and Willdan Energy Solutions, 2023)

Draft General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Grand Portage National Monument / Minnesota (December 2001)

Emergency Prevention and Response Plan For Viral Hemorrhagic Septicemia National Park Units and the Grand Portage Indian Reservation within the Lake Superior Basin (March 14, 2008)

Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Grand Portage National Monument / Minnesota (August 2003)

Forest Health Monitoring at Grand Portage National Monument: 2014 Field Season NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GLKN/NRR—2015/1072 (Suzanne Sanders and Jessica Kirschbaum, November 2015)

Foundation Document, Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (December 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (January 2017)

Geologic Map of Grand Portage National Monument (November 2018)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Grand Portage National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2019/2025 (Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, October 2019)

Grand Portage (Lawrence J. Burpee, extract from Minnesota History Bulletin, Vol. 12 No. 4, December 1931)

Grand Portage: A History of the Sites, People, and Fur Trade (HTML edition) (Erwin N. Thompson, June 1969)

Grand Portage as a Trading Post: Patterns of Trade at "the Great Carrying Place" (Bruce M. White, September 2005)

Grand Portage in the Revolutionary War (Nancy L. Woolworth, extract from Minnesota History, Vol. 44 No. 6, Summer 1975)

Grand Portage National Monument Preliminary Soil Survey NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/GLKN/NRTR-2009/188 (Ulf Gafvert, June 2009)

Grand Portage Rises Again (Willoughby M. Babcock, extract from The Beaver, Outfit 272, September 1941)

Great Lakes Junior Ranger Activity Book (Date Unknown)

Historic Disturbance Regimes and Natural Variability of Grand Portage National Monument Forest Ecosystems (Mark A. White and George E. Host, April 2003)

Historic Documents Study: Grand Portage National Monument (Bruce M. White, August 2004)

Historic Structures Report-Historic Data Section: Grand Portage National Monument — Great Hall (Erwin N. Thompson, May 1970)

If These Walls Could Speak: Using GIS to Explore the Fort at Grand Portage National Monument (21CK6) (Scott Hamilton, James Graham and Dave Norris, July 23, 2005)

Implementation of Long-Term Vegetation Monitoring Program at Grand Portage National Monument Great Lakes Network Report GLKN/2008/07 (Suzanne Sanders, July 2008)

Initial Inventory of the Moths of the Grand Portage National Monument, Cook County, Minnesota (David B. MacLean, July 30, 2002)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Grand Portage National Monument (2019)

Late Prehistoric Cultural Affiliation Study: Grand Portage National Monument (Caven Clark, Archaeological Consulting Services Ltd., November 9, 1999)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Grand Portage National Monument (2005)

Maintenance Area Preliminary Survey Report: Grand Portage National Monument (Douglas A. Birk, February 2006)

Mercury in streams at Grand Portage National Monument (Minnesota, USA): Assessment of ecosystem sensitivity and ecological risk (Kristofer R. Rolfhus, James G. Wiener, Roger J. Haro, Mark B. Sandheinrich, Sean W. Bailey and Brandon R. Seitz, extract from Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 514, 2015)

Mill Creek Road Realignment and Bridge Construction Environmental Assessment (February 2023)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Grand Portage National Monument (Thomas P. Busch, April 22, 1976)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Grand Portage National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRPO/NRR-2014/783 (George J. Kraft, David J. Mechenich, Christine Mechenich, Matthew D. Waterhouse, Jen McNelly, Jeffrey Dimick and James E. Cook, March 2014)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Grand Portage National Monument (Revised July 2014) NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRPO/NRR-2014/842 (George J. Kraft, David J. Mechenich, Christine Mechenich, Matthew D. Waterhouse, Jen McNelly, Jeffrey Dimick and James E. Cook, revised August 2014)

Night-calling Bird Survey 2002-2004, Grand Portage National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/GLKN/NRTR-2008/134 (L. Suzanne Gucciardo and David J. Cooper, November 2008)

Of Sextants and Satellites: David Thompson and the Grand Portage GIS Study (David J. Cooper, 2004)

Park Newsletter (The Grand Portage Guide): 2003 • 2004 • 2006 • 2007 • 2008 • 2009 • 2010 • 2013 • 2011 • 2014 • 2015 • 2016 • 2017 • 2018

Park-specific Brief: Grand Portage National Monument: How might future warming alter visitation? (June 20, 2015)

Potential Impact of Btk (Bacillus thurinigiensis var. kurstaki), Used to Slow the Spread of the Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar Linnaeus), on Non-target Lepidoptera at Grand Portage National Monument, Cook County, Minnesota (David B. MacLean, February 2009)

Resource Brief: Amphibian Monitoring at Grand Portage (December 2023)

Resource Brief: Recent Climate Change Exposure of Grand Portage National Monument (July 25, 2014)

Resource Brief: Long-term Forest Change in Great Lakes National Parks (September 2016)

Resource Brief: Forest Structure In and Around Great Lakes National Parks (October 2016)

Shoreline Map, Grand Portage National Monument (2013)

Short-term Change in Forest Metrics at Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota (Suzanne Sanders and Jessica Kirschbaum, extract from The Canadian Field-Naturalist, Vol. 131 No. 2, 2017, ©The Ottawa Field-Naturalists' Club)

Songbird Monitoring in the Great Lakes Network Parks: 2014-2018 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GLKN/NRR-2021/2217 (Samuel G. Roberts, Zachary S. Ladin, Elizabeth L. Tymkiw, W. Gregory Shriver and Ted Gostomski, January 2021)

The Grand Portage Story (Carolyn Gilman, ©Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1992)

The Story of Grand Portage (Solon J. Buck, extract from Minnesota History Bulletin, Vol. 5 No. 1, February 1923)

Vegetational Analysis of Grand Portage National Monument from 1986-2004 (David B. MacLean and L. Suzanne Gucciardo, April 8, 2005)

Wildland Fire Management Plan and Environmental Assessment (Final), Grand Portage National Monument (September 2004)

The Voyageurs and Their Songs (Minnesota Historical Society / Université De Moncton, undated)

grpo/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025