|

Guadalupe Mountains

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter I:

INTRODUCTION

Guadalupe Mountains National Park, authorized by an act of Congress in 1966 and established in 1972, comprises 76,293 acres of mountain and desert land in West Texas. Congress established the park for its scientific and scenic values. The park consists primarily of the highest and southernmost portion of the Guadalupe Mountains, a range that extends northeasterly into New Mexico. The escarpments and canyons of the high country provide dramatic displays of geological sequences and contain relict and unusual plant communities. Of the area within the park's boundaries, 46,850 acres are Congressionally designated wilderness. This designation precluded extensive development within the park and has limited the uses of much of the park to hiking, horseback riding, backpacking, and approved scientific research.

Location, Access, and Public Facilities

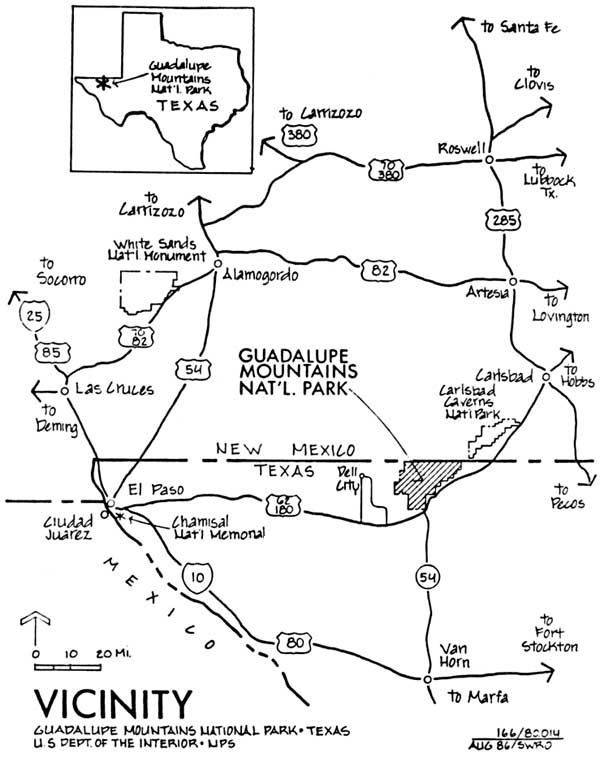

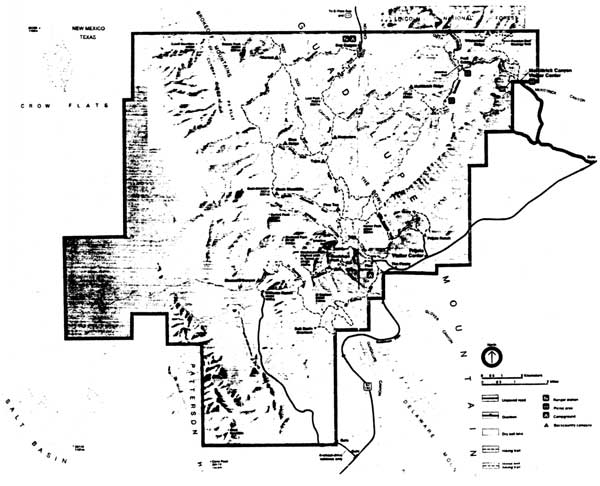

Guadalupe Mountains National Park is located on the Texas- New Mexico Border, 110 miles east of El Paso, Texas, and 55 miles southwest of Carlsbad, New Mexico (see Figure 1). Part of the northern boundary adjoins the Lincoln National Forest and lands controlled by the Bureau of Land Management. Other mountain ranges lie within or in proximity to the park: the Brokeoff Mountains to the north, the Delaware Mountains, Patterson Hills, and Sierra Diablo Mountains to the south (see Figure 2). U.S. Highway 62/180 passes through the southern end of the park and is the primary route by which visitors reach the park. State Road 137 in New Mexico provides access to the northern part of the park.

The park is located in an undeveloped and sparsely populated area where the land is used predominantly for cattle and sheep ranching. However, another national park--Carlsbad Caverns--is only 35 miles away on Highway 62/180 and at one point the boundaries of the two parks are only five miles apart. The tourist facilities that have been developed along the highway between El Paso and Carlsbad consist primarily of small cafe-gas stations. Dell City, Texas, a farming and ranching community with a population of about 400, is the town nearest to the park, but it has only limited services for tourists. A larger development of tourist facilities is located at Whites City, New Mexico, approximately 35 miles northeast of the park. Van Horn, Texas, 60 miles south of the park, also has tourist facilities. Guadalupe Mountains National Park provides the only campground between Whites City and Hueco Tanks, a state park on the eastern outskirts of El Paso.

Physical Description

Included within the boundaries of the park are the sheer cliffs and peaks more than 8,000 feet high that make up the V-shaped southernmost extension of the Guadalupe Mountains. The mountain range is an uplifted segment of the Capitan reef, a limestone barrier reef that formed some 280 million years ago from algae in a shallow inland sea. The geological information revealed in the sheer escarpments and deeply incised canyons of the Guadalupe have made this exposed portion of the Capitan reef one of the world's best-known and most-studied fossil reefs.

|

| Figure 1. Vicinity of Guadalupe Mountains National Park |

|

| Figure 2. Map of Guadalupe Mountains National Park |

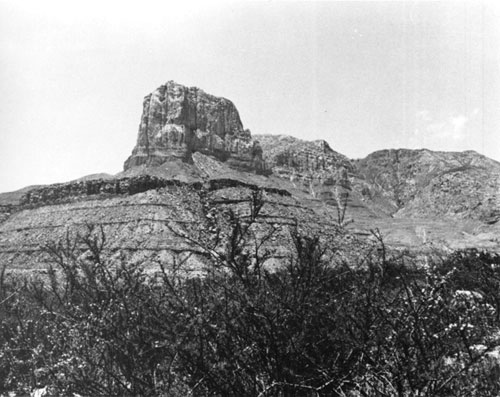

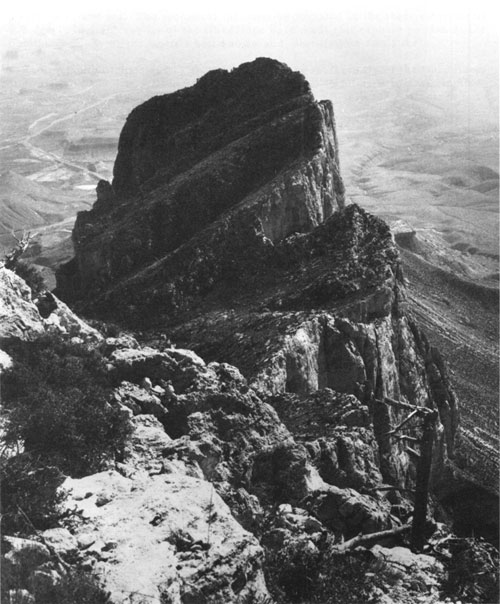

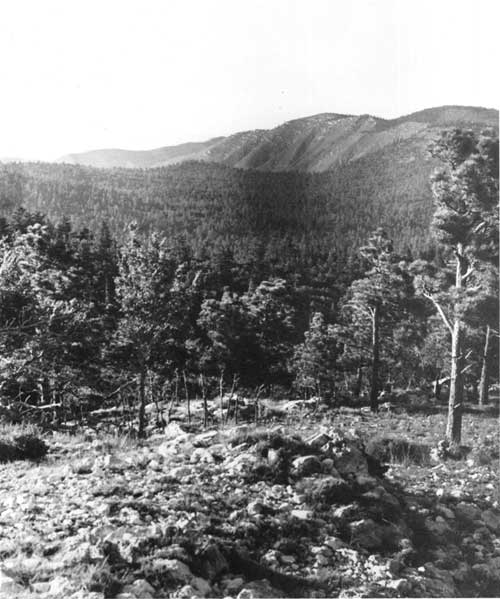

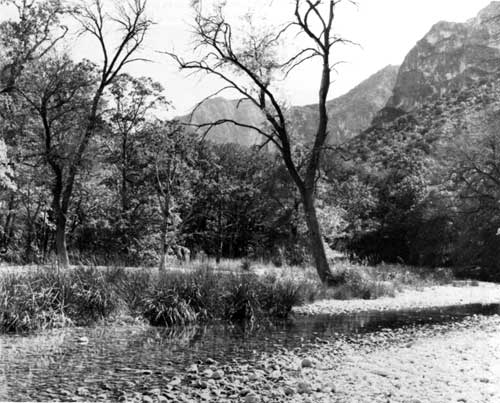

The precipitous cliffs of El Capitan punctuate the southern tip of the Guadalupes and jut above the desert floor like the prow of a great ship (see Figure 3). In 1858, a traveler, seeing El Capitan for the first time, wrote: "It seemed as if nature had saved all her ruggedness to pile up in this colossal form. . . ." [1] Visible for many miles from both east and west, the peak has served as a landmark for travelers for unnumbered centuries. Northeast of El Capitan are the four highest peaks in Texas: Guadalupe Peak at 8,749 feet, Bush Mountain at 8,631 feet, Shumard Peak at 8,615 feet, and Bartlett Peak at 8,513 feet. The top of the escarpment offers unparalleled views of the Delaware basin to the east and the salt basin to the west (see Figures 4 and 5). Hidden between the escarpments that form the V-shaped terminus of the Guadalupe range are two other manifestations of the scientific and scenic values preserved in the park: the relict forest in the Bowl and the aquatic habitat of McKittrick Canyon (see Figures 6 and 7). The unique and fragile variations of plant life in these areas create a museum-like atmosphere, vestiges of a time when the climate of this land was less arid.

The park also includes desert lowlands. The western side of the park encompasses a portion of the salt basin lying between the Guadalupes and the next range of mountains to the west, the Cornudas. These lowlands contain flora and fauna typical of the Chihuahuan desert of which they are a part. They also exhibit the ecological changes caused by overgrazing of domestic livestock. Williams Ranch, one of the park's cultural resources, located at the base of the mountains on the west side of the park, gives visitors a sense of the isolation of a rancher's life. The ranch site also provides a dramatic point from which to view the steep scarp of the western side of the Capitan reef (see Figure 8). On the eastern side, the park does not extend far beyond the base of the mountains. The park lands there are characterized by deep and mostly waterless canyons that lead to the high country.

Although the variations in elevation in the park may produce extremes of temperatures, the climate of the park is generally mild. During the summer the pine forests of the high country offer a cool respite from the intense heat of the desert lowlands. In winter, the lower elevations and west side of the park remain comfortably warm even when snow blankets the mountains. Strong winds in late winter and spring and severe electrical storms accompanied by torrential rains during the summer pose some natural hazards for hikers.

The scarcity of water determines the patterns of life in the park lands. Although an extensive variety of animals, from large ungulates to the smallest mammals, make their homes in the park, the water available from small springs scattered throughout the park dictates their numbers and ranges. Similarly, the locations of these water sources became the camping places of nomadic peoples and the settlements of early ranchers. McKittrick Canyon contains the only perennial stream in the park. The rarity of perennial streams in this arid region has made McKittrick Canyon more than just "the most beautiful spot in Texas," as its former owner called it; the canyon is a showplace for biotic associations otherwise unknown in western Texas and southern New Mexico. [2]

|

| Figure 3. El Capitan, as seen from the southeast. Visible for many miles from both east and west, the peak has served as a landmark for travelers for unnumbered centuries. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 4. View from Guadalupe Peak, overlooking El Capitan. At 8, 749 feet, Guadalupe Peak is the highest point in Texas. A five-mile-long trail makes it possible for park visitors to reach the summit of Guadalupe Peak. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 5. The view down Guadalupe Canyon toward Guadalupe Pass from a high point on the Guadalupe escarpment. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 6. View of the Bowl from a high point on the Guadalupe escarpment. The Bowl contains a relict forest that is one of the park's primary natural resources. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 7. Scene in McKittrick Canyon. McKittrick Canyon contains an oddity in arid West Texas--a perennial stream. The stream is a vestige of a time when the climate of the area was less dry and may be considered a museum of unusual aquatic and biotic associations. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 8. Williams Ranch (left center), one of the park's cultural resources, in its isolation at the foot of the western escarpment and El Capitan. The west side of the park is a favored place for winter and spring visitors for it remains comfortably warm even when the mountains are blanketed with snow. |

Previous Uses of the Park Lands

Although there is no evidence of permanent settlement in the park lands until the late nineteenth century, archeological evidence suggests that nomadic people, whose existence was based on hunting and gathering, utilized the natural resources of the mountains and desert lands for at least ten thousand years before Europeans arrived in the area. In historic times the Guadalupe Mountains served as a last refuge for the Mescalero Apaches as the westward movement of the nation's frontier encroached upon their hunting grounds and way of life. [3]

In the late 1840s, after Mexico had ceded the lands of the Southwest to the United States, the federal government began identifying routes for westbound emigrants. In 1849, Capt. Randolph B. Marcy of the U.S. Army camped on the salt flats west of the park lands and wrote of the Guadalupe Mountains: "The peak of Guadalupe and the general outline of the chain can be seen from here, and it appears to be impossible to pass through it with wagons anywhere north of our route; and as the defile is near the peak, which can be seen for many miles around, it is a good landmark." [4] The route became well known; in 1858 the Butterfield Overland Mail established a stagestop called the Pinery at the top of Guadalupe Pass. A year later, however, the stage line abandoned the facility and began using a more southerly route through the Davis Mountains. The protection offered by U.S. Army troops stationed at Fort Davis and better availability of firewood, water, and grass made the southern route more advantageous. Emigrants, soldiers, freighters, and drovers, however, continued to camp at the Pinery site well into the 1880s. [5]

In the 1870s, after the Apaches had been subdued and gathered onto reservations, settlers moved into the region and took up farming and ranching. In the early 1920s, Wallace Pratt and some friends purchased more than 5,000 acres in McKittrick Canyon. Pratt soon became sole owner of the property and managed the canyon as a nature preserve and place for scientific study. Thirty years later he donated a portion of his ranch in McKittrick Canyon to the federal government to be used as a park.

At the same time that Pratt and his friends bought the land in McKittrick Canyon, J. C. Hunter and two associates also were acquiring land in the southern Guadalupe Mountains. Hunter, like Pratt, bought out his friends, eventually acquiring some 72,000 acres, which he managed as a hunting preserve and cattle, sheep, and goat ranch. In 1969, three years after Congressional authorization to establish a park in the southern Guadalupes, the federal government purchased Hunter's ranch. The Pratt donation and the Hunter purchase made up the bulk of the lands that became Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

Administration of the Park

After Pratt donated McKittrick Canyon to the federal government and until 1972, when Guadalupe Mountains National Park was officially established, the park lands were administered as a detached unit of Carlsbad Caverns National Park. In 1972 the Park Service initiated joint administration of the two national parks. From a central office in Carlsbad, New Mexico, a Superintendent and a full range of support staff managed both parks. Beginning in 1973, an Area Manager who lived at the park oversaw the day-to-day operations at Guadalupe Mountains. John Chapman served in that position from 1973 to 1975. Bruce Fladmark took over the duties of Area Manager in 1976 and served until 1980, when Ralph Harris arrived. Harris was the last permanent Area Manager for the park. In June 1987 Harris transferred out and Park Service management decided that the time was right to appoint a full-time Superintendent for Guadalupe Mountains. In October 1987 Karen Wade accepted the position. [6]

Joint administration of the two parks was beneficial to Guadalupe Mountains in the early years. At that time, Carlsbad Caverns National Park was nearly fifty years old and had the staff and funding of a well-established park. In the first few years of Guadalupe's operation, the park had only a few full-time employees; in times of need they could draw on the skilled employees and equipment available at Carlsbad Caverns. Similarly, the Carlsbad Caverns Natural History Association, an organization established to aid the park through publication and sale of informational material, assisted the interpretive effort at Guadalupe Mountains. Profits from the Association's book sales at the park were used to purchase interpretive equipment that otherwise would have been unavailable. [7]

By 1987 Guadalupe Mountains had matured. Most major developments planned for the park were complete or were scheduled for construction. The park had its own full-time interpretive, maintenance, and ranger staffs. Visitation to the park had increased steadily from 50,000 in 1975 to more than 160,000 in 1986, an indication that the park had developed its own image and clientele. Managers agreed that the time had come to separate the management of the two parks. In the interest of cost efficiency, however, some personnel management, budgeting, and property and procurement functions continued to be performed by the Carlsbad Caverns National Park Administrative Division Office in Carlsbad. [8]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

gumo/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 05-May-2001